In the summer of 1673, Elkanah Settle was luxuriating in the afterglow of The Empress of Morocco, a smash hit that galvanized a new dramatic form: the “horror plays” that would captivate spectators until the end of the decade.Footnote 1 His pleasure was short-lived. A few months after the premiere, Dryden, Shadwell, and Crowne published Notes and Observations on the Empress of Morocco (1674), a savage pamphlet attack on Settle, his play, and his audience. The preface lambasted The Empress of Morocco as “a Rapsody of non-sense” that “but for the help of Scenes and Habits, and a Dancing Tree” would not have pleased even “the Ludgate Audience.”Footnote 2 Settle was called an “upstart illiterate Scribler,” “an Animal of a most deplor’d understanding, without Reading & Conversation,” and “a perpetual Fool.”Footnote 3 Especially mocked was Settle’s “[i]mpudence” in trumpeting how the Earl of Norwich gave the play “a noble Education, when you bred it up amongst Princes, presenting it in a Court-Theatre, and by Persons of such Birth and Honour, that they borrow’d no Greatness from the Characters they acted.”Footnote 4 The name-calling did not reflect well on the triumvirate, but Settle had been deliberately provocative in fashioning himself as the bright new thing lionized by aristocratic tastemakers. Boldly styling himself on the title page as a “Servant to his Majesty,” he included the prologues written by the Earls of Mulgrave and Rochester for the court performance. Dryden would have found the Rochester prologue especially provocative. As the dedication to Marriage A-la-Mode discloses, the dramatist still considered himself to be the peer’s principal client: “I became your Lordship’s … as the world was made, without knowing him who made it; and brought onely a passive obedience to be your Creature.”Footnote 5 The ever-mercurial Rochester, however, was quickly losing interest in Dryden; indeed, he was about to promote Crowne to write the court masque, Calisto.Footnote 6 Equally inflammatory was Settle’s naming the speaker of the court prologues: Lady Elizabeth Howard, who happened to be Dryden’s wife and the sister of courtier-dramatists Robert, James, and Edward Howard.Footnote 7 Effectively, the prologue publicized not only Dryden’s loss of the most renowned tastemaker of the decade but also the dispossession of a wife who had been pressed into the service of a detested rival.

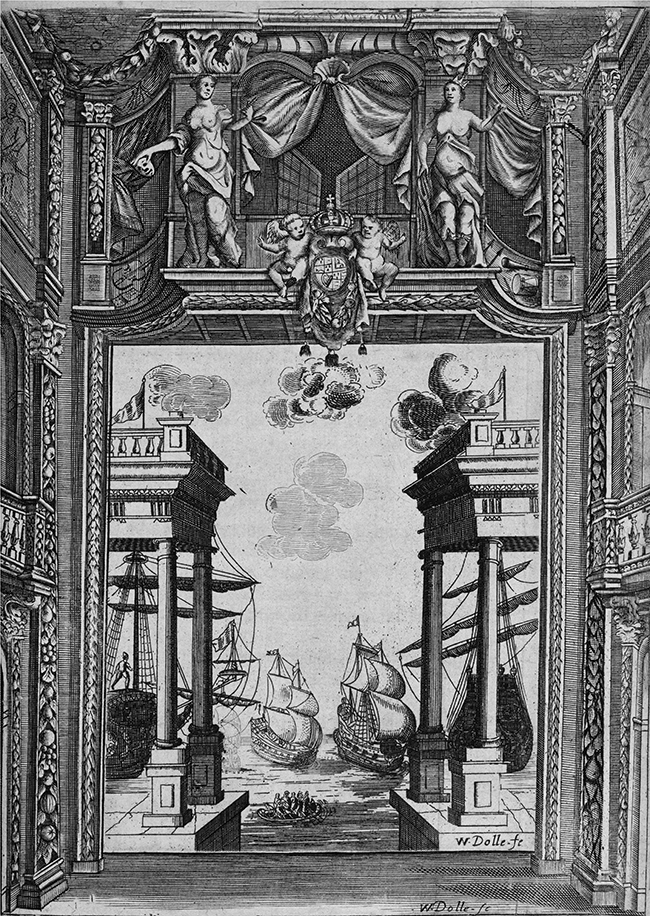

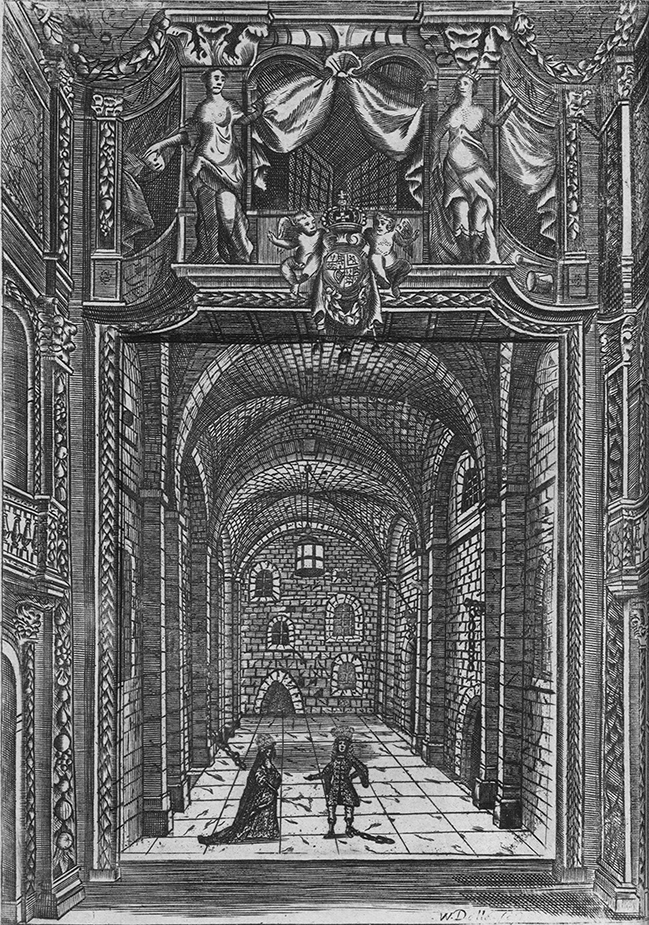

These moves were cheeky enough, but the first edition also featured five illustrated scenes, or “Sculptures,” from the play (Figures 5.1 and 5.2).Footnote 8 If the court prologues reveal a young pup marking territory belonging to others, the “Sculptures” indicate a bolder move: the establishment of new turf. Entirely unprecedented was Settle’s inclusion of expensive illustrations in a perfectly ordinary play quarto that could be purchased unbound for a shilling in any bookstall across town.Footnote 9 Because of the additional “Sculptures,” as they were called, the price of the play doubled. Notes and Observations on the Empress of Morocco sarcastically likens this extra “charge” to “the double rates at Foolish operaes,” thus affiliating illustrative with theatrical excess, never mind that all three of Settle’s enemies would themselves eventually work in “operaes.”Footnote 10 The “Sculptures” nettled precisely because they revealed that Settle had accomplished what his better-known rivals never achieved or perhaps even considered as a possibility: the ornamentation of a plain little quarto with embellishments more befitting a glamorous folio tome.

Figure 5.1 “Sculpture,” from The Empress of Morocco, 1673, book engravings, Folger Shakespeare Library

Figure 5.2 “Sculpture,” from The Empress of Morocco, 1673, book engravings, Folger Shakespeare Library

Settle’s various effronteries could have been overlooked as the ambitions of a hungry newcomer. The offended trifecta claimed they were “very well contented to have let it pass, that the Reputation of a new Authour might not be wholly damn’d.”Footnote 11 The arch exchanges, however, quickly degenerated into name-calling and accusations of low birth, generational differences, and even effeminacy. In the Notes and Observations on the Empress of Morocco Revised (1674), Settle was quick to point out that the forty-one-year-old Dryden “is now grown as Ill-natur’d as Old Women in their decay of Beauty, who make it their business to rail against all that’s young.”Footnote 12 Settle pressed home a divide in age that further emasculated Dryden. Whereas his vigor as a “Stripling Poet recommended Settle to the manly tastes of the town, the etiolated “Mr. Dryden, as he has declared himself, designes to please none but his fair Admirers, the Female part of his Audience.”Footnote 13 Dryden, Shadwell, and Crowne retaliated by banishing Settle from their sandbox, an expulsion that clearly rankled him: “They are all Gentlemen, and will neither own me, nor keep me company.”Footnote 14 Still miffed four years later, Settle continued to chip away at the triumvirate’s pretensions to gentility. Shadwell, he acerbically observed, might have “the Birth and Education of a Gentleman,” but he had to put “his Gentility in Print, to let us know he hath it.”Footnote 15 Estranged from literary circles, Settle was determined to launch the final volley.

As is often true of protracted feuds, the resentments had to do with far more than the precipitating event. In the instance of The Empress of Morocco, anger over the ambitions of a literary upstart ignited into a firestorm over class, patronage, and generational differences. As a point of contrast, Elizabethan dramatists seventy years earlier skirmished largely over matters of literary form. The playwrights involved in the “War of the Theatres” between 1599 and 1602, or what Thomas Dekker risibly called “Poetomachia,” squabbled over satire, diction, and questions of style, especially John Marston’s tendency toward bombast.Footnote 16 By the Restoration, insults over literary taste had escalated to attempts at authorial assassination. Dramatists now labored in a marketplace transformed by the duopoly and structured by its attendant values. Engineered scarcity limited slots for new works, as did an inherited backlog of old plays. Close ties between the theatre and the court gave aristocratic tastemakers exceptional cultural authority. At the same time, changes to authorial compensation made writers utterly dependent on the very audiences whose tastes they had been taught to deplore and whose economic authority they feared. The embrace of “great expences” and the pursuit of innovation from 1660 to 1695 created another limited resource over which dramatists now competed: the lavish stagecraft and special effects that cash-strapped companies could only afford to bestow on a handful of shows.

The economic logic of artificially engineered scarcity transformed dramatic authorship into an unforgiving profession, but courtly prestige sprinkled it with the fairy dust of glamour. Any literate scribbler with a penchant for script doctoring could work for Philip Henslowe in 1597. Seventy years later, fame was on offer, but not a decent livelihood. Gobsmacked playwrights nonetheless flung themselves into the arms of a theatre that promised the pleasures of distinction and innovation. Their willingness to do so bequeathed to us the canonical titles we still read and produce, as well as the works we are still rediscovering. While the confluence of the marketplace and the moment incubated these plays, those same conditions eventually killed playwriting as a viable profession. The turn toward a theatre of prestige put unprecedented class pressure on playwrights, and most writers accordingly hailed from the gentry or the professional classes and were educated at the Inns of Court. Those of modest origins invented for themselves the lineage that might justify membership in the club. Restoration playwrights thus found themselves in the most contradictory of positions: on the one hand, affecting the gentility necessary to write for the restored stage and, on the other, chasing after diminishing opportunities like any common hack. It is little wonder that so many, like Settle and his detractors, undertook bloody feuds, resented their audiences, self-destructed, or simply disappeared after one or two efforts. Toward the close of the century, several dramatists banded together in a poignant attempt to shore up what little dignity remained to the profession. And Dryden, the only playwright whose long career resembles the productivity of Shakespeare, spent the last two decades of his life trying to escape from economic conditions he found intolerable. The theatre of prestige and “great expences” did not usher in the rise of the “literary” playwright; rather, it decimated dramatic authorship by the end of the century.

Generationality, Social Status, and Authorial Self-Fashioning

As the dispute over The Empress of Morocco reveals, professional playwrights were obsessed with the gentility that guaranteed entry into a theatre that was both socially elite and technologically innovative. Evident everywhere is authorial anxiety over status, from Durfey’s decision to add the aristocratic apostrophe to his family name (“D’Urfey”) to obsessive name-dropping in dedications. Included on play quartos were titles such as “Esq.,” “Gent.,” or “Person of Quality.” Seventy years earlier, Shakespeare, despite his aspirations for a family coat of arms, was content to be identified as “William Shakespeare” (the 1600 quarto of A Midsommer nights dreame), “M. William Shak-speare” (the 1608 quarto of King Lear), or simply “W. Shakespeare” (the 1600 quarto of The Merchant of Venice).Footnote 17 Ben Jonson similarly refrained from affixing “Esquire” or “Gentleman” to the title page of his controversial 1616 Workes.Footnote 18 The unprecedented publication of his plays and poems in a folio format may have trumpeted Jonson’s ambitions, much to the derision of his contemporaries, but he stopped short of claiming origins belied by his decidedly common birth.Footnote 19 By contrast, several Restoration dramatists had no such compunction in disguising their background. This was a theatre for gentlefolk, not bricklayers.

Generational change produced another form of status insecurity. The professionals of the 1670s gradually replaced the gentlemen amateurs who dominated the theatres during the 1660s, and the new generation could not help but detect the long shadow cast by their aristocratic predecessors. At the King’s Company especially, most of the playwrights penning plays in the 1660s were related through complicated kinship ties to the monarch himself. Charlotte-Jemima-Henrietta-Maria Boyle, the illegitimate daughter of Charles II, married the playwright James Howard, who in turn was the nephew by marriage of the Earl of Orrery, another dramatist, and the brother-in-law of John Dryden, the most famous writer of the period. Charlotte Boyle’s mother happened to be the sister of Thomas Killigrew, manager of the King’s Company. John Dryden married into the influential Howard clan, which produced three gentleman-amateur dramatists: James, Edward, and Sir Robert. As Nancy Klein Maguire observes, virtually all of these writers or members of their family held official appointments in the government.Footnote 20 Their domination of the theatrical marketplace in the 1660s enshrined courtliness and good birth as essential for the working professionals coming up through the ranks in the following decade. As a result, most professional dramatists after the Restoration hailed from the gentry and the professional classes. As Raymond Williams notes, this change in origins departs sharply from the background of writers earlier in the century: those authors born between 1630 and 1660 came from a “more limited and a more clearly class-based culture than that which preceded it.”Footnote 21

Restoration playwrights did not draw divisions between “university wits” and common writers in the manner of their predecessors, a social distinction that was now meaningless given that most – the men, at any rate – had attended university.Footnote 22 Dryden studied with the renowned classicist Richard Busby at Westminster School before proceeding to Trinity College Cambridge, while Shadwell matriculated at Gonville and Caius College Cambridge. In his teens, Wycherley was sent to France, where he imbibed salon culture at the feet of Julie d’Angennes, the brilliant précieuse daughter of the Marquise de Rambouillet, before returning home for further education at The Queen’s College Oxford, and the Inner Temple. Crowne went to Harvard College in the American colonies before returning to England. Etherege’s grandfather was a prosperous vintner who paved the way for his son to manage properties in Bermuda before making an advantageous marriage and securing a place at the court of Charles I. Those connections ensured Etherege’s apprenticeship to an attorney before he began his legal education at Clement’s Inn. By the outset of the Restoration, Etherege already enjoyed modest wealth. Ravenscroft was admitted first to the Inner Temple and then to the Middle Temple. Lee took advantage of the extensive library compiled by his father, a prominent Anglican clergyman, before proceeding to Trinity College Cambridge, the same college Dryden had attended fifteen years earlier. Otway attended Winchester College before being admitted as a commoner of Christ Church, Oxford. Although little is known about Banks’s family background, he apparently had the means to attend the New Inn. The next generation of literary playwrights followed suit: Congreve attended Trinity College Dublin, as did Thomas Southerne.

Only Settle, Durfey, and Behn remain apart from this profile, and all three undertook various strategies to reinvent themselves as the gentlefolk required by the theatrical marketplace. Settle, the son of a barber whose Oxford education was financed by his uncle, impugned the gentlemanly status of Dryden, Shadwell, and Crowne in the debate over The Empress of Morocco, a defensive maneuver perhaps intended to deflect questions about his own modest origins. Durfey not only adopted an aristocratic apostrophe but also claimed to have been intended for the law. The Inns of Court, however, have no record of his attendance, and contemporary accounts suggest he was apprenticed to a scrivener before turning to playwriting. Known for farcical plays and popular songs that appealed to citizens and their apprentices, Durfey nonetheless “cultivated a name-dropping, gentlemanly vanity” and “hired a page to attend him when he travelled in public.”Footnote 23 In her allegedly autobiographical novella Oroonoko (1688), Behn uses first-person narration to hint teasingly at exotic colonial origins and fashion herself as the daughter of a gentleman who was the “lieutenant-general of six and thirty islands, besides the continent of Surinam.”Footnote 24 The reality was altogether more pedestrian: Behn was in all likelihood the humbly born daughter of a barber in Wye, Kent.Footnote 25

Playwrights seized every opportunity to advertise or, in some cases, manufacture gentility. Several dramatists, however, declared their status as working professionals in an attempt to forge a writerly identity apart from the privileged playwrights of the 1660s. In bowing to marketplace pressures, Behn may have styled herself as the fictive daughter of a colonial lieutenant-governor, but in the essay prefacing Sir Patient Fancy, she acidly distinguishes between dramatists like herself, who are “forced to write for Bread and not ashamed to owne it” and men of “wit” who “write for Glory.”Footnote 26 In the “Epistle to the Reader” prefacing The Careless Lovers (1673), Edward Ravenscroft similarly justifies the practice of dedicating plays to patrons as being “excusable in them that Write for Bread, and Live by Dedications, and Third-Dayes.”Footnote 27 Otway laments in the dedication to the Earl of Dorset prefacing Friendship in Fashion “the circumstances of my condition, whose daily business must be daily bread.”Footnote 28 So pervasive was the social distinction between gentlemen writers and mere hacks that it migrated from the environs of the playhouse to the culture at large. Remarques on the Humours and Conversations of the Town distinguishes between those that “write a Play: which is a kind of fantastical necessity imposed by fashion on a Gentleman” and “a mercenary Poet, who ventures for his gain, & not like a Hero.”Footnote 29 Nonetheless, venturing for “gain,” as the next section discloses, was a nigh impossibility for most playwrights.

The Brutalist Marketplace

Professional dramatists hoping to eke out a living largely entered the theatrical marketplace in the 1670s. They were not, however, a monolithic block: as Tiffany Stern reminds us, those who “wrote for bread” ranged from seasoned company writers to occasional dabblers.Footnote 30 Amongst the professionals, only Shadwell and Settle began their careers prior to 1670. Both Dryden and Etherege, who respectively premiered plays in 1663 and 1664, balanced authorial need with the pretense of gentlemanly avocation. Most emerged in the second decade of the restored theatre: Behn made her debut in 1670 with The Forc’d Marriage; Wycherley in 1671 with Love in a Wood; Crowne that same year with Juliana, or, The Princess of Poland; Ravenscroft in 1672 with The Citizen Turned Gentleman; Duffett and Henry Nevil Payne in 1673 with The Spanish Rogue and The Fatal Jealousie respectively; Lee in 1674 with The Tragedy of Nero, Emperor of Rome; Otway in 1675 with The Rival Kings; and Durfey in 1676 with The Siege of Memphis. Nahum Tate was a relative latecomer, arriving on the scene in 1680 with The Sicilian Usurper, his adaptation of Richard II. Except for Behn, Durfey, and Shadwell, few dramatists produced more than a handful of plays, and Dryden alone comes close to approximating the output of Shakespeare earlier in the century. Equally common were the men and women who penned the solitary play or two and then vanished: writers such as William Joyner, Elizabeth Polewheele, Joseph Arrowsmith, Frances Boothby, and Edward Cooke.

Unfortunately, the new professionals of the 1670s began their careers just as the theatrical marketplace tipped into precarity. As Chapter 4 details, the playhouses during this decade competed with increasingly popular music concerts, not to mention the expanded bourses brimming over with global commodities. New bucolic pastimes, such as spas and pleasure gardens, also tempted consumers. Few were the smash hits in this decade, while the Restoration habit of long runs and revivals further chipped away at the box office. Consequently, many new plays did not make it to the third performance whereby the dramatist might realize a profit minus operating expenses. The new professionals also bumped up against a substantial repertory of preexisting plays – a byproduct of a literate theatre that had been accumulating scripts since the 1580s. Restoration dramatists thus grappled with the paradox endemic to playwriting: the very skills that make them so valuable early on eventually guarantee their obsolescence. Unlike an actor, who functions simultaneously as the producer and product of their labor, the dramatist creates a product that no longer requires further participation unless the acting company wants help with casting in addition to what we would now anachronistically call “direction.”Footnote 31 After a while, playwrights are estranged even from these basic theatrical functions. As repertories expand over time, companies eschew writers for performance specialists, a recurrent pattern in literate theatrical traditions from ancient Greece to seventeenth-century Japan. Once dramatists no longer contribute significantly to rehearsal and performance, they are reduced to producing the occasional new play for a theatre saturated by a backlog of old scripts.

Exacerbating this structural pattern was the historical oddity of the Restoration stage, which was built on a foundation of what Downes called “Old Stock Plays” because of the enforced closure of the theatres from 1642 until 1660.Footnote 32 Except for James Shirley, Davenant, and Killigrew, none of the pre-Civil War playwrights was alive after 1660, and it would take a decade to develop a new generation of professionals. Both companies thus resuscitated a few scripts from the old King’s Company repertory and consequently established a habit of recycling and adapting older works, as discussed in Chapter 2. Additionally, the crushing expenses associated with a theatre predicated on luxury and improvement left little working capital for dramaturgy. For short periods in the late 1670s and early 1690s, the companies set aside their customary reluctance to invest in new works, perhaps hoping to attract spectators back to the theatres after periods of political tumult and woeful box office. By comparison to the Elizabethan stage, however, these occasional efforts were paltry indeed. From 1677 to the end of 1682, the two patent companies produced eighty-five new plays over five years, which averages to seven per annum for each company.Footnote 33 By contrast, the Admiral’s Men staged fifty-two new plays between 1594 and 1597, an output of seventeen plays per annum.Footnote 34 Effectively, the Admiral’s Men exceeded by 65 percent what the Restoration companies staged during an exceptional period of new play development.

As might be expected, companies responded to shifting circumstances when deciding whether to invest in new work. After the collapse of the King’s Company in 1682, the lack of competition diminished the need for more than two or three playwrights. The number of new works produced yearly dropped to 3.8 per annum, a reduction of 73 percent from the high point in the late 1670s. As the actor–playwright George Powell noted, the 1680s were an especially brutal decade for writers: “The reviveing of the old stock of Plays, so ingrost the study of the House, that the Poets lay dorment; and a new Play cou’d hardly get admittance, amongst the more precious pieces of Antiquity, that then waited to walk the stage.”Footnote 35 He nonetheless considered the employment of eight dramatists in the 1690/91 season to be excessive: “As you had such a Scarcity of new ones then; ‘tis Justice you shou’d have as great a glut of them now.”Footnote 36 This “glut” may have been a response to the cessation of the Glorious Revolution. The Battle of the Boyne on July 11, 1690, settled the question of succession, and James II was now exiled to France. With the country enjoying political stability for the first time in several years, the company undoubtedly sought to lure spectators back to the playhouse with what The London Stage calls “an unusually large number of new plays.”Footnote 37 Three years later, the United Company returned to their usual practice of employing a handful of established playwrights (Durfey, Crowne, Southerne, Settle, Congreve, and Betterton) to write six new plays annually. The same occurred in 1695. After Betterton, Barry, and Bracegirdle decamped to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the resulting competition prompted both companies to commission eight dramatists for the 1696/97 season. Two years later, the new breakaway company hired only five playwrights and Rich’s company a mere four. The investment in new plays clearly did not produce the desired outcome. In a grim letter written in January 1699 to Lady Lisburne, Elizabeth Barry reports that regarding “the little affairs of our house I never knew a worse Winter.”Footnote 38 Throughout the Restoration, this would be the pattern: brief periods of splashy outlays on stagecraft, dramatic operas, or a “glut” of dramatists followed by an abrupt retreat when those additional expenditures did not produce box office gains.

Given how few new scripts were produced in most seasons, companies were especially loath to invest in novice playwrights, as a close examination of the 1672 season discloses. Of the new plays produced, two were by Dryden (Amboyna and The Assignation), one by Shadwell (Epsom-Wells), one by Settle (The Empress of Morocco), one by Behn (The Dutch Lover), and one by Ravenscroft (The Careless Lovers). Joseph Arrowsmith and Henry Nevil Payne, both unknowns, wrote The Reformation and The Morning Ramble respectively, both of which vanished shortly after their premiere. Additionally, Payne had a tragedy, The Fatal Jealousie, produced in August, just before the start of the theatre season. According to Downes, both “were laid aside, to make Room for others; the Company having then plenty of new Poets.”Footnote 39 In brief, out of nineteen titles cycling through the repertory, roughly half were new plays. Of these, two were written by a contracted professional (Dryden), one by an established freelancer (Shadwell), four by up-and-coming (albeit known) freelancers (Behn, Ravenscroft, Duffett, and Settle), and two by new writers who subsequently disappeared from the theatre scene. Moreover, four of the nineteen titles were adapted in-house by members of the acting company, a trend that would accelerate toward the end of the century. In the 1690/91 season, for instance, eight new titles were produced by five established professionals (Southerne, Dryden, Settle, Shadwell, and D’Urfey) and three by in-house actors (Mountfort, Powell, and Harris). Newcomers were shut out entirely.

Numbers such as these reveal the intrinsic conservatism of the theatrical marketplace. As a result, playwrights hoping to secure a toehold on the authorial ladder rarely pushed generic boundaries at the outset of their careers. Behn debuted with what Hume calls “rather old-fashioned tragicomedies”: The Forc’d Marriage (1670) and The Amorous Prince (1671), both of which paid homage to the dramatic form closely associated with the founder of the company, the late William Davenant.Footnote 40 Neither did well at the box office. Once Behn was better known, she turned to comedy, her specialty going forward. Lee’s first effort, The Tragedy of Nero, closely followed the horror play formula inaugurated by Settle’s The Empress of Morocco: plenty of gore, torture, madness, and the requisite ghost. Again, the dedication hints the play did not do well.Footnote 41 Durfey similarly stuck to established forms for his initial effort, the heroic drama, The Siege of Memphis (1676). It, too, did not prosper. Even Wycherley, who would become renowned for edgy, lashing satires, such as The Country Wife (1675) and The Plain Dealer, showed considerable caution when starting out. Both Love in a Wood and The Gentleman Dancing-Master draw heavily upon two comedies written in the previous decade by gentleman dramatists: Etherege’s The Comical Revenge; or, Love in a Tub (1664) and Sedley’s The Mulberry Garden (1668). That circumspection did not pay off. Love in a Wood nosedived after one performance. According to a bill for a revival at Drury Lane in 1718, it had been “Acted but once these Thirty Years.”Footnote 42 The Gentleman Dancing-Master made it to six performances but “being like’t but indifferently, it was laid by to make Room for other new ones.”Footnote 43 New playwrights thus found themselves in the conundrum still faced today by fledgling screen or television writers. On the one hand, the reluctance of companies to invest in unknowns inhibited newcomers from splashing out with groundbreaking new works. On the other, by emulating established formulae, early career playwrights risked boring spectators already sated by tired plots.

Dryden’s pensions and unique shareholding arrangement allowed him a degree of creative freedom that newcomers, desperate for production and wholly dependent on the box office, did not dare attempt at the outset of their careers. Between 1668 and 1678, the years of his agreement with the King’s Company, Dryden experiments with such curiosities as Tyrannick Love, a heroic drama about the martyrdom of St. Catherine; Amboyna, a blank-verse domestic tragedy about the massacre of English settlers by the Dutch; and, strangest of all given his high church and royalist beliefs, The State of Innocence (1678), a drama in couplets based on Paradise Lost (1667) that never made it to production. None of these scripts follows box office trends – quite the opposite, in fact – and no one else in the period works in such a vast expanse of dramatic forms, ranging from farce, to comedy, to opera, to tragicomedy, to serious drama. Dryden, however, enjoyed an unusually privileged status until he left the employ of the King’s Company. Just as Shakespeare did seventy years earlier, he owned shares in the company to which he was under contract. He also had pensions from the laureateship and the post of Historiographer Royal. Although the court often reneged on payment, these income streams nonetheless allowed Dryden to push generic boundaries in a manner less privileged playwrights dared not try.

Because opportunities were few in any given season, dramatists ventured beyond the commercial theatre to augment their income, hardly a new authorial ploy. Early modern playwrights such as George Peele, Thomas Dekker, Anthony Munday, and Middleton had penned pageants for civic entertainments. Over a dozen playwrights wrote masques for the early Stuart court, another lucrative source of freelance work. With two notable exceptions, however, court masques largely vanished after the Restoration.Footnote 44 Crowne at the behest of Charles II (and the recommendation of the Earl of Rochester) wrote Calisto for a court production in 1675. The expatriate Huguenot novelist Anne de La Roche-Guilhen followed up two years later with Rare en Tout (1677), a medley of “musique et de balets” that were “represantée devant Sa Majesté.”Footnote 45 Except for this brief flurry of activity in the mid-1670s, court masques were not a viable option for dramatists seeking additional sources of income. As for civic entertainments, these had the unpleasant whiff of populism. Prestige-minded Restoration dramatists thus spurned opportunities to write for the Lord Mayor’s Show or the guild entertainments that earlier dramatists had seized upon. Settle’s willingness to write for money earned him scorn from his contemporaries. The Session of the Poets (1696) pillories him for penning “Drolls for Bartholomew-Fair, and Love Letters for Maid-Servants, Ballads for Pye-Corner.” Settle is further castigated for his willingness to “write an Epithalamium on any Marry’d Person to get Half a Crown.”Footnote 46 So long did the smell of populist ignominy stick to Settle that forty years later Alexander Pope, in Book III of The Dunciad (1743), his mock-epic attack on the literary marketplace, lampooned him for having stooped to fairground entertainments.Footnote 47

Given the opprobrium associated with popular literary forms, status-obsessed dramatists seeking additional sources of income turned to more respectable endeavors, producing translations (as did Dryden and Behn), penning amatory fiction (as did Behn), writing eulogistic occasional poems (as did Tate and Lee), creating poems in prevailing neoclassical forms (as did Dryden, Shadwell, Etherege, and Congreve), or, in a gesture of abject desperation, scribbling angry verse satires against prevailing marketplace conditions (as did Otway). Some of these undertakings paid off handsomely. Dryden was reputed to have earned between £910 and £1,400 for his translation of Virgil.Footnote 48 Others simply opted out of the theatre after producing a handful of scripts, and revealingly, with the notable exception of Dryden, none of the more literary-minded professionals was prolific. Etherege bailed after three comedies and elected to become a diplomat to Ratisbon. Wycherley left after writing four plays, and Congreve decamped after five plays and an opera libretto. Dramatists inclined to write for popular tastes, such as Ravenscroft and Durfey, plugged away over thirty years, but their output suggests the difficulties they faced. Between 1672 and 1697, Ravenscroft managed to have only eleven scripts staged, an average of one every two years or so. Durfey, despite the popularity of his farces and songs, did not fare much better. He premiered his first script in 1676 and had twenty plays produced over thirty years, about one every eighteen months. His last three efforts, the burlesque opera The Two Queens of Brentford, the tragedy The Grecian Heroine, and an opera, Ariadne, all published in a single volume in 1721, were unproduced.Footnote 49

In addition to drastically reducing the demand for new works, the principle of engineered scarcity curtailed authorial compensation by creating a buyer’s market. Put simply, there were far more playwrights eager to sell scripts than there were available slots for production. Consequently, Restoration acting companies did not have to follow the earlier English practice of paying for scripts on demand. In 1600, dramatists received between £5 and £8 per script, averaging £25–£35 per annum.Footnote 50 That was far better than what a skilled journeyman craftsman could earn but less than the £40–£50 yearly income a yeoman or country parson might expect.Footnote 51 Dramatists received the occasional gratuity, such as the 5s. given to Charles Massey by the actor and manager Edward Alleyn, and they could also earn money from script doctoring and writing for civic entertainments.Footnote 52 By 1613–14, rates for freelance scripts had at least doubled, if not tripled, rising from £6–£8 to £20 per script, as indicated by extant correspondence between the dramatist Robert Daborne and Henslowe.Footnote 53 Contracts also reveal a steady uptick in compensation. By the mid-1630s, Richard Brome earned 15s. weekly or £39 annually as his base salary, a figure that does not include his poet’s benefit. Three years later, Brome renegotiated his salary to 20s. weekly or £52 per annum, a remarkable increase of 33 percent.Footnote 54 The escalation in authorial payment corresponded to marketplace conditions: with half a dozen playhouses operating at full capacity and the companies carefully balancing revivals with premieres, new scripts were in demand. For seasoned playwrights, it was a seller’s market, and their product became increasingly valuable by the 1630s, as attested by the increase in fees paid to established dramatists such as Alexander Brome and James Shirley.

The French neoclassical stage offered an alternative and potentially more remunerative model of authorial compensation. The Restoration companies, however, had little financial incentive to reward writers handsomely when scripts could be had so cheaply from dramatists desperate to gain a toehold on a precarious theatrical ladder. French playwrights received a company share minus operating expenses for every performance of a play.Footnote 55 By the early 1660s, payment had swelled to two shares for a five-act play, which meant for the playwright, “if the play was a success, he could earn quite a large sum of money.”Footnote 56 Racine’s tragedy Iphigénie (1674) was reported to have played for forty performances, a run that virtually guaranteed the author – especially at two shares of profit per performance – a very handsome return. Even though he was a newcomer, Phillippe Quinault in the 1650s negotiated a one-ninth share of the box office rather than the 150 livres usually paid for a play by a fledging playwright.Footnote 57 If the dramatist was a member of an acting company, as was true of Molière, he would realize the usual actor’s share in addition to the writer’s shares of the box office.

Evidence suggests that a handful of English playwrights received contracts, especially early in the Restoration, when new plays were needed to leaven an inherited prewar repertory. In 1668, Dryden signed an exclusive contract with the King’s Company that give him one and a quarter shares, essentially the same arrangement that Shakespeare had enjoyed earlier in the century.Footnote 58 In return, he was to write three plays a year, an understanding that lasted for ten years, until Dryden left for the more financially stable Duke’s Company.Footnote 59 Apparently, Lee was also under contract to the King’s Company, although unlike Dryden he was not a shareholder; even so, in the dedication to Theodosius (1684), Lee claims his plays were produced “once or twice a Year at most,” a prospect that will “just keep me alive.”Footnote 60 Crowne appears to have had a “like agremt” for a while with the Duke’s Company.Footnote 61 An anonymous pamphlet attack against Settle suggests that a company contract could substitute for the poet’s benefit: “The Duke’s House allowed Mr. Settle fifty Pounds a Year upon Condition they might have the Acting of all the Plays he made. But he expecting a greater third day, if acted by the King’s Servants, notwithstanding his Pension, put his Play into their Hands.”Footnote 62 According to Cibber, the breakaway company at Lincoln’s Inn Fields offered Congreve a contract after the enormous success of Love for Love “in Consideration of which he oblig’d himself, if his Health permitted, to give them one new Play every Year.”Footnote 63 As these examples suggest, contracts were not a common form of authorial compensation; rather, they were tendered to successful playwrights, such as Dryden or Congreve, or during moments when the need for new scripts was uncommonly pressing, such as the first decade of the restored theatre or the outset of the breakaway company at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Most professional dramatists – Dryden was a notable exception – depended solely on the box office for their sustenance. As Milhous and Hume point out, “management decided to shift the risk to the playwright … what the playwright got depended on success in the theatre.”Footnote 64 The profit minus operating expenses was set aside from the third performance for dramatists, but even this was reengineered after the Restoration to their disadvantage. The Actors Remonstrance, or Complaint (1643) describes how prior to the closure of the theatres in 1642, the “ablest ordinarie Poets” enjoyed both “annuall stipends and beneficiall second-dayes.”Footnote 65 This statement reveals that prior to the Civil War, a script had to survive just one day past the premiere for the dramatist to receive his poet’s day; moreover, that benefit supplemented his “annuall stipend.”Footnote 66 This doubled form of compensation disappeared after the Restoration. Paulina Kewes maintains that several attached playwrights were given a cash retainer for the right of first refusal, but she does not provide supporting evidence for this statement.Footnote 67 Moreover, delaying the poet’s day to the third performance made it more difficult to realize a profit, especially for the newcomers who had not yet galvanized a following.Footnote 68

Because of their abject dependence on the box office, some playwrights sought assistance from aristocratic tastemakers whose approval might secure their poet’s day. Several factors account for the exceptional cultural authority wielded by these titled luminaries. As previously discussed, several peers wrote for the theatre in the 1660s, and many of the early dramatists at the King’s Company had kinship ties to the Stuarts. The duopoly further amplified their dominance over the marketplace. And, finally, the hierarchical nature of late seventeenth-century society privileged aristocratic tastes over those of commoners, who were expected to follow the lead of their betters. Courtesy books enjoined gentry and citizens to give a “Person of Quality … leave to judge first, by attending his approbation” and “to forbear till that Person of Quality applauds or condemns it, and then you may fall in as you see occasion.”Footnote 69 Pamphlets on the theatre, such as A Comparison Between the Two Stages (1702), similarly promoted the aesthetic authority of peers: “what the Quality approve, the lower sort take upon trust.”Footnote 70 As a result of this cultural conditioning, aristocratic endorsement could realize a handsome return for a playwright. When the Duchess of Richmond attended the poet’s day performance of Lee’s Theodosius, her presence guaranteed “a Subsistence for him all the Year after.”Footnote 71 According to a letter from Lord Granville to Sir William Leveson, the attendance of James II at Crowne’s Darius, King of Persia (1688) gave it “a most extraordinary third day” despite the lackluster script.Footnote 72 A Comparison Between the Two Stages describes how Congreve’s comedy Love for Love (1695) had “the Town … ingag’d in its favour,” and the appearance of “Noble Persons … in the Boxes, gave the House as much Advantage as their Contributions.”Footnote 73 An anonymous letter quoted by Edmond Malone describes how the presence of “the town,” along with nobleman such as “my lord Winchelsea” (Daniel Finch, 2nd Earl of Nottingham and 7th Earl of Winchilsea), gave Southerne a poet’s day profit of £140 for his tragedy The Fatal Marriage, or the Innocent Adultery (1694). He additionally received gifts of “guineas apiece” from “50 noblemen.”Footnote 74

Nobility could use their considerable cultural authority to nudge a production toward success, but they could also wield that same power against a playwright who had run afoul of their politics or offended their literary sensibilities. A notorious instance of the former occurred when the French Catholic mistress of Charles II, the Duchess of Portsmouth, took exception to The Female Prelate (1680), an anti-Catholic play written by Settle at the height of the Popish Plot crisis. The play premiered on Monday, May 31, 1680. On Wednesday – Settle’s poet day – “the Dutchesse of Portsmouth to disoblige Mr Settle the Poet carried all the Court with her to the Dukes house to see Macbeth.”Footnote 75 The tactic worked: Settle’s play quickly disappeared. Peers could also doom plays that displeased them. Dryden recounts in a letter to William Walsh how “the two noble Dukes of Richmond and St. Albans were chief managers” of the catcalls that torpedoed Durfey’s comedy The Richmond Heiress; or, A Woman Once in the Right.Footnote 76 Out of sheer pique, the Duchess of Marlborough, who “at that Time bore an irresistible Sway,” cut short the run of Abel Boyer’s tragedy Achilles; or, Iphigenia in Aulis (1700), which had premiered at Drury Lane. Instead, she “bespoke” Farquhar’s The Constant Couple, “the Comedy then in Vogue” running concurrently at the rival playhouse.Footnote 77 Again, the strategy worked: Boyer’s tragedy, although much admired by Dryden and others, disappeared for fifteen years.

Occasionally, playwrights had exceptional hits that did not require the assistance of peers. Shadwell evidently earned more money from The Squire of Alsatia (1688) than any playwright previously. Running “13 Days altogether,” it garnered him an unprecedented £130 “at single Prizes,” although it is not entirely clear what that phrase means.Footnote 78 Downes, however, provides these details precisely because of their singularity; far more common were the lackluster or failed runs that beleaguered dramatists throughout the Restoration. In chronicling thirty-five years of performances for the Duke’s and the United Company, Downes names only fifteen occasions when a play ran over six days, roughly once every two years.Footnote 79 If the mentions of “great profit” to the company are included (which do not detail how long a play ran), then the number doubles to roughly one hit per season. Most of these successes occurred before the novelty of the reopened theatres had abated; revealingly, Downes mentions instances of “great profit” three times more frequently in the 1660s than the 1680s. Available data reveal other suggestive patterns. Davenant’s own works comprise a goodly portion of the early hits for the Duke’s Company: The Siege of Rhodes, twelve days; The Wits, eight days; and The Rivals, nine days.Footnote 80 Although Downes does not provide the length of the run for Love and Honour, he claims it “[p]roduc’d to the Company great Gain and Estimation from the Town.”Footnote 81 Downes is also explicit about the money Davenant bestowed upon his own shows: The Siege of Rhodes had “new Scenes and Decorations,” while Love and Honour was “Richly Cloath’d.”Footnote 82 Given that lavish spectacle drew crowds, it appears that Davenant spent company resources on his own scripts in order to guarantee their box office success while denying that largesse to others.

Newcomers could expect little in the way of compensation. Hopefuls such as John Dover, Lewis Maidwell, Samuel Pordage, Joseph Arrowsmith, Thomas Rawlins, Elizabeth Polwhele, Thomas St Serfe, John Leanerd, William Chamberlayne, Nicholas Brady, and John Caryll rapidly disappeared after one or, at most, two efforts, and few, if any, realized their poet’s day. More sobering were the established professional writers who became ill and destitute in either mid- or late career: Lee died broke in Bedlam; Otway perished drunk in a gutter; Crowne and Wycherley subsisted on royal charity at the end of their lives; Banks died in debt to creditors; Settle became a poor brother of the Charterhouse; and Behn, desperate for money shortly before her death, pleaded for advances from her publisher, Jacob Tonson. Even Dryden, the magisterial figure of the period, was so impoverished at the end of his life that friends had to underwrite the cost of his funeral.Footnote 83 Edward Ravenscroft and Thomas Duffett both vanished, their fates unknown. Shadwell alone prospered. A stalwart Whig, he benefited from the regime change ushered in by the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Among other perquisites, he acquired the poet laureateship and office of Historiographer Royal seized from Dryden, who was now suspect politically and theologically. Of dramatists who died before 1700, Shadwell alone left a significant estate.Footnote 84

“The Applause of Fools”

Compensation practices put dramatists at the mercy of spectators. James Thompson notes the “peculiarly hostile relationship between playwright and audience” during the Restoration, and many professional writers openly resented their abject dependence upon the box office.Footnote 85 Disdain for spectators was also an aristocratic pose, another byproduct of the uncommonly close association between the court and the commercial stage cemented by the duopoly. In “An Allusion to Horace,” the Earl of Rochester mocks “the false judgment of an audience / Of clapping fools, assembling a vast crowd / Till the thronged playhouse crack with the dull load.”Footnote 86 Similarly, Dryden’s brother-in-law Edward Howard is revulsed at the prospect of submitting “to the giddiness of vulgar applause, there being nothing more unstable or erroneous than vox populi in point of plays.”Footnote 87 Professional dramatists aped aristocratic scorn for audiences. In the preface to Sir Patient Fancy, Behn laments the necessity of writing for the popular tastes of audiences and admits it is “a way I despise as much below me.”Footnote 88 That desire to transcend the abjection of the box office only intensified over time. In the preface to The Lucky Chance, written eight years later, she declares bravely, “I am not content to write for a Third day only”.Footnote 89 Shortly before her death, in the preface to The Emperor of the Moon (1687), Behn wearily dismisses spectators as an unthinking mass, mere “Numbers, who comprehend nothing beyond the Show and Buffoony.”Footnote 90

Otway similarly resented spectators and turned to peers for the approbation. The preface to Don Carlos, Prince of Spain (1676), derides “such as only come to a Play-house to see Farce-fools, and laugh at their own deformed Pictures.”Footnote 91 He especially dismisses those that were “very severe” on his play: “Whoever they are, I am sure I never disoblig’d them, nor have they (thank my good fortune) much Injur’d me: in the mean while I forgive ’em, and since I am out of the reach on’t, leave ’em to chew the Cud on their own Venom.”Footnote 92 Against this popular opinion, Otway pits “the greatest party of men of wit,” especially the “Earl of R. who far above what I am ever able to deserve from him, seem’d almost to make it his business to establish it in the good opinion of the King, and his Royal Highness, from both of which I have since received Confirmations of their good Liking of it, and Encouragement to proceed.”Footnote 93 Two years later, Otway had fallen out of favor with Rochester and out of love with the theatre. In the savage prologue to Friendship in Fashion, he advises parents to “Breed” their sons “to wholesome law, or give ’em trades” since “Poets by critics are worse treated here, / Than on the Bankside butchers do a bear.”Footnote 94 Rather than endure continued abasement at the hands of spectators or neglect from a mercurial patron, Otway obtained a commission as ensign in a foot regiment and disappeared abroad for eighteen months before returning to London.

Despite the economic refuge afforded by his shareholding agreement with the King’s Company, Dryden resented his dependence on the audiences he largely detested. In the preface to An Evening’s Love, or The Mock-Astrologer, Dryden complains of feeling “often vexed to hear the people laugh, and clap, as they perpetually do, where I intended ‘em no jest; while they let pass the better things without taking notice of them.”Footnote 95 Like his brother-in-law Edward Howard, he was especially concerned not to cede to spectators the authority to the determine aesthetic worth of his plays. In the “Defence of an Essay of Dramatique Poesie,” Dryden argues that even though “the liking or disliking of the people gives the Play the denomination of good or bad, [it] does not really make, or constitute it such.”Footnote 96 Revealingly, Dryden’s misgivings about spectators become more pronounced after he joins the Duke’s Company and finds himself in the same position as other professional dramatists that depended solely on the box office. What begins as occasional grumbling about audience taste in the 1660s swells by 1680 to near-operatic denunciations. Dryden muses bitterly about the futility of authorial effort and resolves in the preface to The Spanish Fryar, or, The Double Discovery (1681) to “settle my self no reputation by the applause of fools.”Footnote 97

Tellingly, Dryden’s dramatic output plummeted after he left the refuge of the shareholding agreement. In the 1680s, he wrote only three scripts, two of which did not fare well. The controversial Don Sebastian (1689) appears never to have been revived after its premiere, and the opera Albion and Albanius failed, saddling the United Company with considerable debt. The libretto for King Arthur languished for seven years before it finally saw production.Footnote 98 Dryden turned increasingly to poetry and translation after 1678, and he composed during this period the remarkable long poems Religio Laici (1682) and The Hind and the Panther (1687). He also ushered into print an English translation of Plutarch’s Lives (1683). Having lost both the laureateship and the post of Historiographer Royal in 1689 because of his unwillingness to recant his conversion to Roman Catholicism, Dryden hints in the melancholy dedication to Amphitryon (1690) that “this Ruin of my small Fortune” is responsible for his grudging return to the stage.Footnote 99 The bitter preface two years later to Cleomenes makes apparent his contempt for “the barbarous Party of my Audience.”Footnote 100 “No body can imagine,” Dryden confides miserably, “that in my declining Age I write willingly, or that I am desirous of exposing, at this time of day, the small Reputation which I have gotten on the Theatre. The Subsistence which I had from the former Government, is lost; and the Reward I have from the Stage is so little, that it is not worth my Labour.”Footnote 101 Penury nonetheless necessitated another stint in the jailhouse of authorial abjection.

Playhouse factions could make or break a dramatist’s fortunes – yet another cause for authorial distrust of audiences. In the pamphlet debate over The Empress of Morocco, Settle sneered at Dryden for writing “to please none but his fair Admirers, the Female part of the Audience.” Dryden, however, was smart to do so. As David Roberts illustrates, women in the audience exerted considerable influence over new plays. In several instances, they “cried down” bawdy productions, such as Ravenscroft’s The London Cuckolds (1682) and Wycherley’s The Country Wife, much to the chagrin of the latter.Footnote 102 At the same time, the support of women could prove vastly beneficial. While female spectators “may have been powerless to resist the imputation of conventional kinds of response,” as Roberts observes, they did constitute an important community “who took a responsible interest in the stage, and who exercised independent judgment in pronouncing on what was submitted to them.”Footnote 103 Female spectators tended to reward heroic drama and romance and to punish crude satire and smutty comedies, a predictable response given social expectations regarding female modesty.Footnote 104 Far more fearsome than the “ladies” were the “criticks”: young men of means who had the time and leisure to attend the playhouses and voice loud, often obnoxious judgments. Pierre Danchin’s compilation The Prologues and Epilogues of the Restoration identifies over 160 references to critics between 1660 and 1700. Highly convention-bound, prologues and epilogues sought to predispose the audience favorably toward the production, an aim they achieved with wit, humor, and flattery. Consequently, Harold Love warns against treating them as “photographs from the stage,” and Diana Solomon similarly cautions against their uncritical use as “documentary evidence.”Footnote 105 At the same time, Solomon acknowledges that prologues and epilogues can reveal a “cultural preoccupation,” such as the anxiety occasioned by the Popish Plot and the Exclusion Crisis, both of which surface frequently in paratexts between 1678 and 1682.Footnote 106 The frequency and sheer doggedness with which prologues and epilogues impugn the “Huffing Criticks of the Pit” argue for a similar cultural preoccupation. Numbers also tell a story: complaints about critics more than double after 1675, and they become especially vitriolic when box office falls off.Footnote 107

Contemporary evidence suggests that fear of privileged young men with nothing better to do than ruin new plays had a sociological basis in fact. In the advice book he penned to Charles II upon the eve of the Restoration, Newcastle especially worried about the lack of occupations for younger sons:

[A] gentle man would put his younger son, to the universety, then to the Ins of Courte, to have a smakering in the Lawe, afterwards to wayte of an Embasador, afterwardes, to bee his secretary, Then to bee Lefte as Agente, or resedent, behind him, then sent of many forrayne Imployments, – & after some 30 yeares Breeding, to bee made a Clarke of the Signett, or a Clarke of the Counsell, – itt may bee afterwards, Secretary of state.Footnote 108

Newcastle maps out a clear professional path for the younger sons of gentry and minor nobility who would not, given the English practice of primogeniture, inherit an estate but would nevertheless be assured of upward mobility by placement in a succession of increasingly important offices. That changed, according to Newcastle, after James I, “when great Favoritts Came In … whoe soever would give a thousand pound more for the place.”Footnote 109 Although the gentry “disposed of their sons otherwise, as to the Gospell, the Lawe, & to bee merchants,” the Inns of Court and the Church could absorb only so many young men of education and breeding.Footnote 110 As they had in the past, these young men sought places and preferment, but chronic insolvency hobbled the Restoration court, as discussed in Chapter 1. In addition to an overproduction of elites were the sheer numbers of young people living in the capital. The demographer Gregory King estimated that by 1696 over half the population of London was under twenty and that more than a quarter – approaching 28 percent – were “Batchelors” and “Maidens.”Footnote 111 Without work that was both gainful and socially acceptable, educated “batchelors” especially would find less productive outlets for their energies.

For privileged youth without an occupation, the playhouse conferred cultural authority otherwise denied by their status as aimless younger sons. Even their location in the playhouse amplified their social importance; according to Henri Misson, they occupied the pit, which was filled with “Men of Quality, particularly the younger sort.”Footnote 112 Harsher in tone is The Country Gentleman’s Vade Mecum, which describes the occupants as “Judges, Wits and Censurers, or rather the Censurers without either Wit or Judgment.”Footnote 113 Seated below the stage in a benched area easily viewed by everyone in the playhouse, these “Censurers” were impossible to ignore. Retention of the deep forestage from the Elizabethan playhouse put the actors in close proximity to them, and spectators looking down from boxes would see them as easily as they did the performers. Their numbers and their domination of playhouse space swelled over the course of the Restoration, especially as court attendance abated.Footnote 114 Playwrights undertook various defensive strategies to circumvent the potential damage they wrought. One method entailed securing “support for a play before it opened.”Footnote 115 Playwrights either packed the playhouse with friends and patrons or submitted their draft to the critics for approval prior to production. The old-fashioned induction to Edward Howard’s The Man of Newmarket chronicles this latter ploy. The “Prologue” and the actors Joseph Haines and Robert Shatterell catalogue “a sort of people call’d Wits and Sub-wits or Criticks, and Sub-criticks” who line up against “Poets and Sub-poets, &c.”Footnote 116 Shatterell recommends that the “Sub-poet” – perhaps a designation for minor writers – “refer his Papers” to these various classes of wits and critics for approval prior to production. Despite the humorous undertone, that sort of advice could not help but impress upon playwrights their economic dependence on the very spectators whose opinions they often abhorred.

Generationality and Authorial Individualism

Because resources were so straitened, professional writers had little incentive to share earnings with others. As a point of contrast, one-third to one half of all scripts penned seventy years before the Restoration were written as collective endeavors.Footnote 117 By the 1630s, collaboration dropped to 6 percent, and by the time playhouses closed in 1642, solo endeavors were normative.Footnote 118 Indeed, the close association between solitary authorship and professional writing by the time of the Civil War may very well have fueled the aristocratic collaborations of the 1660s and early 1670s – a way for gentlemen amateurs to distinguish themselves from the grubby individualism of those who had to “write for bread.” Sir Charles Sedley, Edward Filmer, the Earl of Godolphin, and Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst and later Earl of Dorset, worked together on Pompey the Great (1663). Sir Robert Howard teamed up with the Duke of Buckingham on The Country Gentleman (1669), an attack on Sir William Coventry. The Duke of Newcastle pulled both Shadwell and Dryden into his orbit on two projects: Sir Martin Mar-all, which according to Pepys was “made” by Newcastle but “corrected” by Dryden, and The Triumphant Widow (1677), which had scenes inserted by Shadwell.Footnote 119 Professional writers, however, largely eschewed collaboration with other professionals. Shadwell may have worked briefly with Newcastle on Jonsonian-style humours comedies, but he pointedly avoided doing the same with someone of his own rank. As the debacle over The Empress of Morocco reveals, relations amongst professional dramatists were more likely to be colored by turf wars than camaraderie.

Although Paulina Kewes attributes solitary authorship in the Restoration to “an emergent belief in the writer’s imaginative autonomy and the concern about the assignment of intellectual property,” that belief had been “emerging” since 1610.Footnote 120 It was hardly a new development.Footnote 121 Additionally, recent scholarship has shown how even Shakespeare – the consummate “man of the theatre” – also had a proprietary interest in publication.Footnote 122 A Restoration writer like John Dryden further complicates the story about emergent authorship. As his prefaces and essays indicate, no one in the period cared more about the writer’s “imaginative autonomy.” At the same time, no other professional writer was more inclined toward coadjuvancy. He happily collaborated with writers such as Nathaniel Lee and frequently paid homage to company managers and actors for their assistance in production. In that regard, Dryden was, as he notes in the prologue to Aureng-Zebe (1676), “betwixt two Ages cast, / The first of this, and hindmost of the last.”Footnote 123 “Hindmost” signifies that which is furthest away in time and suggests Dryden was thinking back to the Shakespearean, not the Caroline stage, when he wrote those lines. Certainly, Dryden’s enthusiasm for experimenting with stagecraft, for working closely with performers, and for collaborating with playwrights and composers is closer to 1600 than 1640.

Generationality may very well have inclined Dryden to straddling these two modes of authorship. The professional playwrights entering the theatrical marketplace after 1670 were, with the exception of Etherege, born between 1640 and 1653: Behn, 1640; Crowne, 1641; Wycherley, 1641; Shadwell, 1642; Settle, 1648; Banks, 1652; Otway, 1652; Durfey, 1653; and Lee, 1653. Later dramatists who scripted plays in the 1690s were not even born until well after the Restoration. With the exception of Lee, none collaborated with other professional writers. By contrast, Dryden (b. 1631) was ten to twenty years older than the other professionals who wrote between 1668 and the early 1680s. He was far closer in age to figures such as Roger Boyle, Earl of Orrery (b. 1621), Sir Robert Howard (b. 1626), and the Duke of Buckingham (b. 1628) than he was to the emergent professionals of the 1670s and later. That divide might explain Dryden’s willingness to emulate their penchant for collaboration. He worked with Davenant on The Tempest and later partnered with Lee on Oedipus (1679) and The Duke of Guise. Toward the end of his career, he worked in the highly collaborative environment of opera, first teaming up with Grabu on Albion and Albanius in 1685 and then with Purcell on King Arthur in 1691.

Dryden’s penchant for working alongside theatre artists shows in other respects. He is the only Restoration dramatist on record to praise actor–managers for their collaborative skills as adapters and editors. He thanks Davenant for teaching him to “admire” Shakespeare and how to augment “the Design” of The Tempest.Footnote 124 His draft from Davenant “received daily his amendments,” and for this reason, “it is not so faulty, as the rest which I have done without the help or correction of so judicious a friend.”Footnote 125 He acknowledges Betterton for assisting him with the design of Troilus and Cressida (1679): “But I cannot omit the last Scene in it [i.e. the third act], which is almost half the Act, betwixt Troilus and Hector. The occasion of raising it was hinted to me by Mr. Betterton.”Footnote 126 And Dryden lauds Betterton fulsomely for scenic improvements to Albion and Albanius: “The descriptions of the Scenes, and other decorations of the Stage, I had from Mr. Betterton, who spar’d neither for industry, nor cost, to make this Entertainment perfect, nor for Invention of the Ornaments to beautify it.”Footnote 127 That same collaborative spirit spilled over to theatrical production, even though Dryden’s enthusiasm went against prevailing trends. The idea that the playwright would oversee rehearsal – common during the Shakespearean period – largely disappeared after 1660. Tiffany Stern attributes this change to increasingly autocratic managers and powerful actors; undoubtedly, the ever-growing backlog of plays and penchant for revivals also sidelined dramatists.Footnote 128 Dryden nonetheless involved himself with every aspect of production, as extant correspondence reveals. In August 1684, he expressed concern to his publisher about two upcoming revivals of his plays at the United Company: was management “making cloaths & putting things in a readiness for the singing opera?”Footnote 129 If Sarah Cooke was not available for the role of Octavia in a revival of All for Love, would Charlotte Butler do?Footnote 130 And was Sue Percival (later Mrs Verbruggen), who normally played in comedies, up to the serious role of Benzayda in The Conquest of Granada ?Footnote 131 Dryden’s concern with casting and costuming – a marked departure from the studied indifference of the gentlemen amateurs – likely galvanized the caricature of him as “Bayes” in The Rehearsal.

Despite Buckingham’s cruel portrait, Dryden nonetheless embarked upon another collaborative enterprise in the final decade of his career. The aristocratic gatekeepers of the 1660s and early 1670s, such as Rochester, Newcastle, and Buckingham, were long gone, and their assistance had been inestimable to dramatists and the acting companies alike. Tastemakers like Rochester not only corrected scripts with an eye toward improvement but also smoothed the way toward production. Dryden famously credits him with making “amendment[s]” to Marriage A-la-Mode and for having “commended it to the view of His Majesty.”Footnote 132 Once the king signaled “His Approbation of it in Writing,” the play then had a “kind reception on the Theatre.”Footnote 133 Sir Francis Fane similarly praises Rochester for his assistance on Love in the Dark (1671), which benefited from “receiving some of the rich Tinctures of your unerring Judgement; and running with much more clearness, having past so fine a strainer.”Footnote 134 Indeed, Fane chalks up any success the play might realize to “your Lordship’s partial recommendations, and impartial corrections.”Footnote 135 Aristocratic gatekeepers functioned much as literary agents do today. By winnowing through newly submitted scripts, they lightened the workload for the acting companies while providing the benefit of their literary judgment. Sir Robert Howard describes in the prefatory essay to The Great Favourite, Or, the Duke of Lerma (London, 1668) how the King’s Company asked him to vet a play by an unnamed “Gentleman” and to “return my opinion, whether I thought it fit for the Stage.”Footnote 136 And in a marketplace as fiercely competitive and with as few slots for new works as the Restoration theatre, their assistance was all the more necessary. A letter from William Beeston to Charles Sackville, Earl of Dorset, provides a glimpse of behind-the-scenes maneuverings by aristocrats hoping to advance their favorites. Beeston asks Dorset for “assistance” with a play “your Lordship vouchsafed to read.” Even though “the Actors commend itt,” the play was evidently “hindred by Persons of Honour writing to prefer for other mens Labours.”Footnote 137 Most striking is that someone of Beeston’s stature felt compelled to seek Dorset’s help to counter unnamed “Persons of Honour” who were promoting their own clients for much-coveted production slots. He was hardly unknown. Beeston had worked for decades as an actor and a manager, but so curtailed were opportunities that even he sought assistance from a peer.

In the 1690s, Dryden stepped into this cultural void. He functioned as an éminence grise for young writers such as Southerne and Congreve and ensured their plays would be considered for production. In both capacities, he was much needed. The rise of the in-house script doctor in the 1690s reduced even further the few slots available for new plays. Fledgling dramatists consequently went to extraordinary lengths to secure a reading. The wildly convoluted circumstances surrounding Congreve’s first play, The Old Batchelor (1693), reveal how hopeful dramatists, lacking the assistance of a Rochester or Buckingham, turned in desperation to family members and friends. Congreve had the advantage of hailing from comfortable Anglo-Irish circles: his father was the Earl of Burlington’s agent in Ireland.Footnote 138 He used those connections to solicit wealthy and well-placed cousins for assistance, and they in turn recommended The Old Batchelor “to a friend of theirs.”Footnote 139 The unnamed friend then “engag’d Mr Dryden in its favour, who upon reading it sayd he never saw such a first play in his life.”Footnote 140 The play, however, was perceived to lack the “cutt of the town,” and so Dryden, along with Southerne and Arthur Manwayring, gave The Old Batchelor the requisite polish. Dryden additionally “putt it in the order it was playd,” essentially reordering scenes and reworking the design.Footnote 141 Two days after the play premiered to resounding applause on March 9, 1693, the Earl of Burlington, who perhaps had been pulling strings from the sidelines, wrote to Congreve’s father approvingly. The play, he reported, was deemed “the best that has been Acted for many years, Monday is to bee his day which will bring him in a better sume of money than the writters of late have had.”Footnote 142 Southerne meanwhile had interceded with Thomas Davenant, manager for the United Company, to allow Congreve “the privilege of the Playhouse half a year before his play was playd.”Footnote 143 This unique arrangement allowed Congreve to see plays for free and perhaps to attend rehearsals as well, a theatrical education that would bear fruit in such masterpieces as Love for Love and The Way of the World. His first play, however, negotiated a gauntlet of five levels of literary gatekeeping before finally realizing production. Earlier in the period, discreet script doctoring and a murmured recommendation by Rochester or Buckingham into the right ear would have gotten the job done.

Other established dramatists stepped into the cultural space vacated by the gentlemen dramatists of the 1660s and 1670s. Shadwell used the authority of the laureateship, which he had taken over from Dryden in 1689, to promote young dramatists. Through his efforts, Nicholas Brady managed to have The Rape; or, The Innocent Imposters (1692) produced. In a letter to the Earl of Dorset on January 19, 1692, Shadwell describes how the script was initially rejected by management: “Thomas Davenant has with a great slight turned him [i.e., Brady] off, and says he will trouble himself no more about the play.” Shadwell petitioned Dorset – now Lord Chamberlain – to “favour” the author and “order” that The Rape will “be the next new play to be acted.”Footnote 144 His intervention worked: by March, the Gentlemen’s Journal refers to the play as already having been produced.Footnote 145 Southerne, fresh off the success of Oroonoko (1696), used his influence to promote Cibber’s comedy Love’s Last Shift (1696). At the outset of his career, as Cibber recounts, so “little was expected from me, as an Author” that he had trouble “getting it to the Stage.”Footnote 146 Southerne listened to Cibber read his play and liked “it so well, that he immediately recommended it to the Patentees.”Footnote 147 Although an in-house, actor–playwright such as George Powell did not need an advocate to secure a reading, he nonetheless understood how the likes of a Dryden might boost a fledgling playwright’s prospects. In the preface prefixing The Fatal Discovery; or, Love in Ruines, Powell sarcastically styles himself as an “unknown Author” who wants “merit enough to appear in full Glory, viz. with an J. Dryden, in Heroicks, in Laudem Autoris.”Footnote 148 Powell nonetheless possessed what by 1698 was arguably more important than literary authority: membership in an acting company. As the next section discloses, publication offered some succor to dramatists worn down by a brutalist marketplace. The book industry, however, was not without its own frustrations.

The Palliative of Print

Dramatists by dint of historical accident possessed after 1660 what they did not have earlier in the century: sole ownership of their play. Prior to the Civil War, acting companies purchased both the performance and publication rights to a script. Once a play manuscript was in their possession, they could withhold it from publication or broker a deal with a bookseller. After the Restoration, the battle over the best plays from the pre-1642 repertory – a dispute ultimately resolved by royal intervention – ensured a principle of performance rights that stayed in place until 1695.Footnote 149 Acting companies no longer needed to possess a physical script to ensure these rights in perpetuity: they had merely to premiere a play. Ownership of the physical text thus fell into the hands of playwrights. Whether as an oversight or as a concession for the erosion of other privileges, dramatists now had the right to sell, edit, or emend their scripts as they pleased for publication.Footnote 150 In 1691, Dryden received “the Sum of Thirty Guinneys,” in exchange for which he assigned to “Mr. Tonson all my Right in the Printing ye Copy of Cleomenes a Trajady.”Footnote 151 An anonymous writer records that for the vastly popular tragedy The Fatal Marriage, Southerne was paid £36 “for his copy.”Footnote 152 Playwrights thus benefited from managerial preoccupation with prestige, specifically the desire to possess the performance rights to the celebrated repertory of the old King’s Company and to the plays of the “big three”: Jonson, Shakespeare, and Fletcher. Publication rights were seemingly of little interest to management.

Several scholars maintain that this newfound right of playwrights to market plays directly to booksellers transformed their literary status.Footnote 153 No longer mere hacks, dramatists were now identified as authors on the title pages to play quartos – a mark of literary authorship that supposedly did not exist previously. Numbers seemingly support this notion. In the 1670s, nearly 80 percent of all printed plays name the author, a number that rises to 96.5 percent by the 1680s.Footnote 154 The attribution of dramatic authorship on title pages, however, was widespread well before the Restoration. In the period between 1621 and 1642, between 90 and 92.5 percent of quartos named the playwright.Footnote 155 Early modern dramatists were just as concerned as late seventeenth-century writers with the visible signs of proprietary ownership. Arguably, what emerged after 1660 was not a hitherto unknown social category for authorship but rather the ends to which publication was now put. Through the medium of print, plays refused production could see the light of day and excised passages could be restored. Publication conferred authorial afterlife and thus resuscitated what had perished on the stage. Even playwrights that never saw their plays produced could through print memorialize their efforts. And, finally, publication permitted the last word or, at the very least, a volley of words, as occurred with the debacle over The Empress of Morocco.Footnote 156 Playwrights weary of the box office or worn down by performance resorted to pamphlets, dedications, prefatory essays, and prologues and epilogues. Through the medium of print, they justified their efforts, responded to audience factions, blamed their enemies, and set the record straight. That these ancillary elements of the play quarto exploded exponentially after 1670 speaks not to the sudden emergence of literary authorship but to writerly discontent with grim working conditions.

Of course, playwrights also had a financial incentive to usher their plays into print, especially given that copyright had fallen into their hands. Remuneration, then as now, correlated to authorial reputation, and a successful production could boost the visibility necessary to attract the attention of potential purchasers. In the preface to The Grove, or, Love’s Paradice, John Oldmixon acknowledges that he “[n]ever knew a Book get much by a Preface, nor a Play by this means advance in the Opinion of the world, unless it had triumph’d on the Stage.”Footnote 157 Despite his previously lackluster career, Southerne received from Tonson £36 for The Fatal Marriage; or, The Innocent Adultery (1694). A smash hit, it transformed overnight a minor-league author into a valuable commodity. Most playwrights would never realize close to that amount. As Milhous and Hume point out, of the plays published between 1660 and 1700, half achieved a second edition and only 18 percent made it to a fifth.Footnote 158 Given these negligible profit margins, booksellers were loath to hazard more than £5 for the copyright to a play.Footnote 159 While hardly a livable wage, £5 was nonetheless meaningful to a dramatist like Lee, who counted himself fortunate to have a play staged “once or twice a Year at most.”Footnote 160 If Lee realized £50 from his poet’s day – an amount, according to Alexander Pope, that was “reckoned very well” during the Restoration – then the sale of copyright boosted that figure by another 10 percent.Footnote 161 Literary luminaries earned considerably more, although even someone of Dryden’s stature had to bargain hard for increases. To lure Dryden away from other booksellers, Jacob Tonson offered £20 for Troilus and Cressida (1679), their first joint imprint.Footnote 162 Despite the popularity of Dryden’s poems, miscellanies, and translations in the 1680s, it took another twelve years and numerous exchanges of sociability before Tonson acceded to a higher payment of £30 for Cleomenes.Footnote 163 Tonson sent melons to Dryden, which the latter pronounced “too good to need an excuse.”Footnote 164 On another occasion, he gave Dryden sherry pronounced “the best of the kind I ever dranke.”Footnote 165 In return, Dryden praised Tonson’s “good nature” and entrusted him with messages for his wife and Congreve.Footnote 166 They met in coffeehouses and taverns to exchange manuscripts and money, and they opined about the state of contemporary letters.Footnote 167 Even so, profit trumped literary friendship.