Modern statutory capital requirements heavily influence banks’ capital levels. In most countries, the regulation of bank capital specifies minimum capital requirements for establishing and running a bank. According to the World Bank’s Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey in 2016, only 5 out of 158 countries did not stipulate a minimum capital requirement.Footnote 1 When joint-stock banks were established in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, capital regulation in two of the three countries analysed in the following – England and Switzerland – was light at best.Footnote 2 Only the United States regulated capital on the state and federal levels.

One of the main reasons for regulating bank capital was the right of individual banks to issue notes, which was monopolised in the United States as late as the 1930s. The concern for an over-issue of banknotes often led to a limitation of note issuing as a multiple of a bank’s capital. Limiting the note issue to a multiple of bank capital is a capital requirement too.

In contrast to the United States, England and Switzerland did not have many note-issuing banks, only one (England) or a few (Switzerland). Therefore, the liabilities side of a commercial bank’s balance sheet looked very different to that of note-issuing banks in the United States. In the case of England and Switzerland, not banknotes but customers’ deposits were the most important balance sheet item on the liability side. Thus, contemporaries compared capital with deposits to measure if a bank’s capital was sufficient.

Comparing capital with the most dominant liability item in the balance sheet is strongly linked to the perception of capital in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The key roles of capital discussed in early banking literature were twofold: Firstly, authors viewed capital as an element to strengthen depositors’ or noteholders’ confidence in the banks and the whole banking system. Secondly, capital served as an absorber for losses.

The advantages and disadvantages of high or low capital ratios were well understood when large commercial banks emerged in England, Switzerland, and the United States. To choose an adequate capital ratio, bank managers considered the conflicting interests of shareholders (in having a high dividend) and those of depositors or noteholders (in having a high capital ratio).

Pursuing capital adequacy has led to the application of various informal and formal rules for capital ratios. Bank managers in England and Switzerland aimed for capital/deposits ratios of about 1:3 when establishing the first joint-stock banks. By the end of the nineteenth century, capital/deposits ratios of 10% were considered sufficient for English banks. In Switzerland, the 1:3 rule of thumb was more persistent. In the United States, banks were usually subject to notes-to-capital limitations. An often-used notes-to-capital ratio was 3:1. Once banknotes’ share in balance sheets decreased and deposits’ relevance increased, supervisors started to use a capital/deposits ratio of 10% as an informal guideline. The US supervisory agencies used the 10% capital/deposits ratio as a yardstick to measure capital adequacy until the 1930s.

What was the basis for such guidelines aiming to quantify adequate bank capital? The nineteenth-century literature on banking published in English and German provides insights into the discussion of capital in banking. The banking literature in the United States, the United Kingdom, and German-speaking countries had shared roots in the form of publications on monetary theory. This common starting point highlighted the relevance of money supply for the economy and emphasised the importance of liquidity in banking. Thus, the goal of monetary control was an important rationale for the regulation of banking. The consequence was a focus on investment doctrines in banks or, more specifically, the maturity of banks’ assets. Within the monetary theory, liquidity concerns dominated, and the discussion of capital adequacy was often only a side product. Beyond the shared roots, publications on banking developed somewhat independently, reflecting country-specific issues such as a country’s monetary and fiscal organisation or economic and banking crises. Finally, a second discipline also emerged in the nineteenth century: one dedicated to the specific banking practice, providing advice for the banker on how to manage a bank.

Given the banking literature, the economic environment, and banking regulation, what was banking practitioners’ perception of the role and adequacy of capital in the nineteenth century? How were capital policies developed in practice? The environment in which banking practitioners operated varied from one country to another. One can find everything from the speculative behaviour of bankers and their shareholders to remarkable (public) self-reflections of bankers on what an optimal level of capital could be. Moreover, the three banking markets varied regarding banking concentration, development, regulation, and frequency of banking crises.

Beyond the analysis of nineteenth century banking literature, this chapter focuses on large banks and their capital policies in England, Switzerland, and the United States. In the case of England, the focus is on the so-called ‘big banks’, which were established from the 1820s. For Switzerland, the group of big banks emerging from the 1850s are analysed. In the United States, capital among the first commercial banks of the 1780s and later the large New York City–based banks is discussed.

3.1 Early Banking Literature: Shared Roots, Different Trajectories

The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries produced a wealth of literature on the theory and practice of banking. James Steuart, for example, published his famous Inquiry into the Principles of Political Economy in 1767. Among other subjects, he also elaborated on banking and summarised contemporary banking knowledge.Footnote 3 Likewise, Adam Smith provided various paragraphs on banking in The Wealth of Nations (1776).Footnote 4 Publications by numerous authors on banking followed on both sides of the Atlantic. The nature of such publications throughout the nineteenth century was usually of two kinds. Many authors engaged in theoretical discussions on topics such as note-issuing, investment doctrines, and liquidity in the banking market, and, more generally, the macroeconomic effects of banking. The second stream of literature was practical in orientation. It dealt with the management of banks and elaborated on specific questions arising from banking practice.

The two streams of literature cannot be separated entirely, as theoretical debates on monetary and banking theory had practical implications. The most prominent example is probably Smith’s real bills doctrine, which argued that banks should engage in short-term lending against real bills (bills of exchange) only. Such bills of exchange originated from the sale of goods and were discounted by banks. Following the arguments of Smith and later proponents of the doctrine, the asset side of a bank would consist of short-term and, thus, ‘self-liquidating’ bills.Footnote 5 The real bills doctrine became the dominating banking doctrine in the nineteenth century, impacting banking practice and theory in the United States and Europe.Footnote 6 The real bills doctrine contrasted the arguments of Steuart, who suggested lending against land as collateral (mortgages).Footnote 7 Guidelines on how banks should invest their assets – as proposed by Steuart, Smith, and others – had obvious practical implications for the individual bank and its lending policy. Beyond the practical relevance, however, these debates also had a theoretical dimension, elaborating on the effects of money supply on the price level.

The publications in different regions and languages showed many interactions too. The literature on banking theory published in the United States and the United Kingdom share its roots, the authors Steuart and Smith being two examples of influential figures contributing to that origin. At the same time, the publications in the United Kingdom and the United States also followed their individual paths throughout the nineteenth century, reflecting on the challenges of the two banking markets.Footnote 8 A similar observation can be made when comparing publications in English and German. Authors writing in German often drew from the contemporary classic English banking textbooks while also dealing with country-specific issues.

Along with growing professionalism in banking during the nineteenth century came publications specifically written for banking practitioners. Moreover, bankers established organisations that dedicated themselves to practical issues and education. The organisations and their publications contributed to the accumulation of knowledge on the management of banks. In London, the Institute of Bankers was founded in 1879. The Institute’s Journal of the Institute of Bankers served as a standard source of information for bankers, covering theoretical issues and answering practical questions. These questions were also regularly published as Questions on Banking Practice from 1885 onwards. Both publications complemented an existing one, The Bankers’ Magazine, founded in 1843, which had quickly become the most relevant publication for bankers in the United Kingdom. In the United States, banking practitioners formed the American Bankers Association (ABA) in 1875. The ABA first published the Journal of the American Bankers Association in 1908. Moreover, The Bankers’ Magazine (not to be confused with the British version under the same title) was published from 1847 onwards.

Banking practitioners and people connected to banking engaged in theoretical debates and published on practical matters. Among the key figures in the United Kingdom were Thomas Joplin, James William Gilbart, Walter Bagehot, George Rae, and later Walter Leaf. Thomas Joplin, one of the early banking theorists, took part in the foundation of various banks, including the Provincial Bank of Ireland in 1825, the National Provincial Bank of England in 1833, and the London and County Banking Co. in 1839. James William Gilbart was the general manager of the Westminster Bank from 1833 to 1860. Walter Bagehot was the secretary of Stuckey’s Banking Company and later editor of The Economist. George Rae worked as general manager and later chairman (1873–98) of the North and South Wales Bank in Liverpool. Walter Leaf was chairman of the Westminster Bank from 1918 to 1927 and president of the Institute of Bankers. Many of their works became ‘classics’ in British banking literature.

Joplin’s An Essay on the General Principles and Present Practice of Banking in England and Scotland (1822) was a pamphlet against the note-issuance monopoly of the Bank of England (BoE) and an analysis of the banking system from a theoretical point of view.Footnote 9 Gilbart authored the two standard textbooks of the time: A Practical Treatise on Banking (1827) and The History and Principles of Banking (1834).Footnote 10 Bagehot’s famous Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market (1873) also featured a chapter on joint-stock banking.Footnote 11 Rae, meanwhile, published The Country Banker in 1885.Footnote 12 Leaf authored the classic textbook Banking in 1927. It was re-published in several editions up to 1943.Footnote 13

Among key figures contributing to the US banking literature of the nineteenth century were Erick Bollmann, John McVickar, Eleazar Lord, Albert Gallatin, George Tucker, Charles Carey, William M. Gouge, and Charles F. Dunbar.Footnote 14 These authors were less involved in banking activities than their British counterparts. Henry Charles Carey was an American publisher and self-trained economist and sociologist.Footnote 15 He wrote on banking in his Essays on Banking in 1816 and Principals of Social Science in 1860.Footnote 16 William M. Gouge was an economist who published A Short History of Paper Money and Banking in the United States in 1833.Footnote 17 Eleazar Lord, financier and economic theorist, published Principles of Currency and Banking in 1829.Footnote 18 Albert Gallatin, who was secretary of the US Treasury from 1801 to 1814, wrote his Considerations on the Currency and Banking in 1831. John McVickar, George Tucker, and Charles F. Dunbar were university professors.Footnote 19 Among these publications, George Tucker provided the most practical treatment of the banking subject.

Banking literature from German-speaking countries emerged later than that in the United Kingdom and the United States. One of the earliest classic publications on banking was Otto Hübner’s Die Banken (1854). It was followed by Adolph Wagner’s Beiträge zur Lehre von Banken three years later. Both Hübner and Wagner were economists from Germany. Other classic publications were written by Max Wirth (Handbuch des Bankwesens, 1870), Adolf Weber (Depositenbanken und Spekulationsbanken, 1902; Geld, Banken, Börse, 1939), and Georg Obst (Banken und Bankpolitik, 1909).Footnote 20 Academics rather than practitioners dominated the German banking literature. Most comparable to the publications of British banking practitioners is Felix Somary’s Bankpolitik, published as late as 1915.Footnote 21 Somary was an Austrian–Swiss banker, economist, and political analyst.Footnote 22

Within the aforementioned publications in German, not a single book missed referring to Gilbart’s banking textbooks. The publication of German magazines covering banking practice evolved only about half a century after its British and US-American equivalents. The Bank-Archiv, for example, was published first in 1901, Die Bank and Zahlungsverkehr und Bankbetrieb from 1908, and the Bankwissenschaft from 1927.

3.1.1 The Link Between Liquidity and Solvency Guidelines

Liquidity rather than capital adequacy was the dominating topic in nineteenth century banking literature. The idea that banks should focus on short-term lending was widespread in the nineteenth century. Many contemporaries thought that the real bills doctrine would allow banks to adjust the asset side flexibly, reducing the risks involved in banking.

In the United Kingdom, the crises of 1847, 1857, and 1866 fostered the view that liquidity was vital in avoiding financial turbulence.Footnote 23 Rae, for example, argued that the ‘financial reserve’ should be one-third of the liabilities to the public in order ‘to guard against all probable demands’.Footnote 24 Similarly, Bagehot highlighted the crucial role of reserves, and that the ‘greatest strain on the banking reserve is a “panic”’.Footnote 25 Financial reserves meant liquid assets such as cash, money at call and short notice, consols, and reserves at the BoE, and are not to be mistaken with reserves built up by retained profits as a form of capital. Similar discussions on liquidity evolved in the United States. Here, too, the ratio of liquid assets (in the US often defined as cash items, specie, and legal-tender notes) to liabilities was constantly discussed, and later authors related to Bagehot’s treatment of the topic.Footnote 26

The two German authors, Hübner and Wagner, also emphasised the relevance of liquidity. Hübner’s book was the first to formulate what came to be known as the famous ‘Goldene Bankregel’ in the German-speaking space. The ‘golden bank rule’ concerned banks’ liquidity and stipulated matching maturities of assets and liabilities.Footnote 27 Three years later, Wagner published a critique of the ‘golden bank rule’, introducing a second famous banking principle: the ‘Bodensatztheorie’. Wagner argued that certain deposits could be used for long-term loans, as not all depositors withdraw their capital simultaneously.Footnote 28 The theory was further extended by the ‘Realisationstheorie’ (in English: shiftability theory) of Karl Knies in 1879.Footnote 29 Knies emphasised the relevance of being able to liquidate assets to ameliorate short-term liquidity problems if needed.Footnote 30 The increasingly differentiated view on liquidity in the German literature developed simultaneously with that in the United States and the United Kingdom, where the shiftability doctrine in banking became increasingly dominant too.Footnote 31 According to the shiftability theory, banks could sell assets (including assets with longer maturities) on the market at short notice, thus shifting their assets to other banks or the central bank in case demand for liquidity increased. The shiftability theory, therefore, relaxed the guidelines of the real bills doctrine and changed the understanding of liquidity.

Despite the similarity in rules for liquidity across the banking literature in German and English, the context of the discussions in banking theory was very different due to the varying monetary environments. It becomes most evident when comparing banking theory in English, focusing on England and the United States.

In England, the BoE had a partial note-issue monopoly from 1708 and received a full monopoly in 1844. In the United States, the First Bank of the United States (1791–1811), the Second Bank of the United States (1816–36), state-chartered banks (until 1865), and national banks were allowed to issue notes, resulting in a high number of note-issuing banks. The Federal Reserve received its note-issue monopoly only in 1935. Given the decentral organisation of the note issue, one of the central concerns in the US banking literature was the over-issue of banknotes.Footnote 32 Many discussions surrounded the topics of asset liquidity and asset diversification (i.e. how to invest as a bank) and the question of whether note issuing should be limited to a particular proportion of a bank’s capital. The limitation of note issuance, however, directly links the two topics of liquidity and solvency. While the central concern of a note-issue limitation is liquidity, it is a solvency rule too. Banknotes are a liability in a bank’s balance sheet. If a bank can issue notes equivalent to three times its capital, it implies a capital requirement of one-third (compared to notes). Thus, liquidity considerations had consequences for capital adequacy guidelines. However, even though bank capital was not the central theme, many authors of banking textbooks had developed a clear understanding of what adequate capital would be.

3.1.2 How Much Capital Is Adequate?

The nineteenth-century banking literature used various terms for what is nowadays defined as equity capital. Gilbart, for example, distinguished between invested capital and banking capital.Footnote 33 The former refers to the capital provided by shareholders (equity capital), the latter to capital raised by the bank through deposits, the issuance of notes, and the drawing of bills (debt capital). In the United States, capital was referred to as ‘capital stock’.

Apart from discussing equity capital, many authors argued that the use of debt capital is what defines a bank. Most famous is probably Bagehot’s statement in Lombard Street (1873), emphasising that ‘a banker’s business – his proper business – does not begin while he is using his own money: it commences when he begins to use the capital of others.’Footnote 34 The idea was not new: in 1827, Gilbart had described the profession of a banker as ‘a dealer in capital’, meaning debt and equity capital.Footnote 35 The US literature also used this idea. Dunbar, for example, highlighted that an ‘establishment becomes in reality a bank’ only if it starts to ‘use its credit’ to discount commercial papers.Footnote 36

Authors across the banking literature in English and German had a clear and common understanding on what the role of capital was. The use of capital was to provide trust and cover losses. In the United States, Gallatin outlined in 1831 that bank capital needs ‘to be sufficient to cover all the bad debts, and all the losses’. At the same time, Gallatin emphasised that the ‘ultimate solvency of a bank always depends on the solidity of the paper it discounts’.Footnote 37 Other authors, such as Lord and McVickar, had already emphasised the trust component in the late 1820s. McVickar wrote that capital provides assurance to creditorsFootnote 38. Lord argued that capital was ‘a necessary basis of public confidence, and a guarantee against the consequences of imprudence, unfaithfulness and casualty’.Footnote 39 Similarly, Bagehot stressed the role of capital as a source of public trust in a bank and a guarantee for its operations.Footnote 40 German economists, such as Hübner and Wagner, shared these views.Footnote 41

In the United Kingdom, only one author ventured to suggest a specific minimum capital/liability ratio for banks. In 1827, Gilbart wrote in A Practical Treatise on Banking:

Although the proportion which the capital of a bank should bear to its liabilities may vary with different banks, perhaps we should not go far astray in saying it should never be less than one-third of its liabilities. I would exclude, however, from this comparison all liabilities except those arising from notes and deposits.Footnote 42

Gilbart derived the requirement probably from two roots. He analysed and referenced the Scottish banking market.Footnote 43 At the time – the late 1820s – joint-stock banks had just started to emerge in England, while Scotland already had a much more established joint-stock banking market. The second possible source is the BoE, which followed the rule of one-third for its metallic reserve (specie) ratio in proportion to notes (paper money).Footnote 44 The rule addressed the liquidity of the bank and its ability to redeem notes for specie. However, such a liquidity guideline has practical implications for capital adequacy too at the time when a bank is established. It raises the question of what equity capital should consist of when paid-in (specie or other assets) at the beginning and what it is invested in when a bank starts to operate.

The probably most advanced discussion of ‘sufficient’ capital in the first half of the nineteenth century was published by Joplin in 1822. Joplin refrained from suggesting a specific figure but made ‘sufficient’ dependent on the efficient use of resources.Footnote 45 The author seemed to have a well-founded idea of how much capital was adequate. In the context of Scottish banking, he noted that the capital of both the Bank of Scotland and the Royal Bank of Scotland were ‘unnecessarily large’. Compared to the trade in Edinburgh and considering the stability of the banks, Joplin argued that they would be equally sound if they reduced their capital by 50%, with beneficial effects for the profit per stock.Footnote 46 With this argument, Joplin had already considered various factors determining a bank’s capital in 1822: the risks involved in the business, the effect of leveraging on returns for shareholders, and the efficient allocation of capital.

For the emerging English joint-stock banks, deposits were a crucial funding source. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, deposits provided 80–90% to the total liabilities of the large joint-stock banks.Footnote 47 Consequently, deposits were used to assess capital adequacy. In 1877, The Bankers’ Magazine first attempted to measure the size of banks’ capital in the United Kingdom.Footnote 48 It noted that a comparison of capital with deposits would have been desirable, but data on deposits was not available for the United Kingdom at the time.Footnote 49 Thus, the magazine was not able to publish capital ratios. Instead, it compared the total amount of capital in the United Kingdom and the United States. As of 1876, the capital of British joint-stock banks was estimated at £87.5m, divided into paid-up capital of £64.3m and reserves of £23.2m.Footnote 50 The capital of US banks reached £143.8m.Footnote 51 The Bankers’ Magazine considered the figures for the United Kingdom’s banks to be comparatively high.Footnote 52 The magazine stressed the importance of capital for public confidence and viewed capital formation in banking as a measure of the progress of banking. Regarding the appropriate level of capital in banking, The Bankers’ Magazine referred to Gilbart’s ‘one-third guideline’, underlining the validity of his views published fifty years earlier.Footnote 53

Thereafter, The Banker’s Magazine published annual reviews of bank capital in the United Kingdom. From 1902, the magazine also began comparing capital and reserves to deposits and all liabilities.Footnote 54 With regard to the optimal capital/liability ratio, The Banker’s Magazine changed its position. In 1903, the magazine stated – for the first time – that no specific ratio should be followed.Footnote 55

However, the move towards a more differentiated view on the adequate size of bank capital seemed to have happened even earlier. In 1885, Rae referred to the capital/liability ratio as a measure of a bank’s ‘ultimate stability’. In contrast to Gilbart’s view on capital adequacy about sixty years earlier, Rae considered the soundness of bank assets as a determining factor for adequate capital. The author emphasised that ‘there is no accepted rule in the matter, and it would be difficult to frame one’.Footnote 56

The German banking literature also offers evidence of an increasingly nuanced view on capital adequacy. In 1873, Wagner wrote extensively about the role of bank capital, viewing it as a form of guarantee for depositors. The guarantee would not necessarily have to take the form of paid-up capital. It could also be an unlimited or limited liability. When making this point, Wagner referred to the British joint-stock banks as an example, noting that ‘a highly magnificent banking operation does not necessarily require a substantial amount of own capital’.Footnote 57 Without providing a specific minimum capital ratio, Wagner concluded that adequate capital would have to be a compromise between the amount, risk, and coverage of assets.Footnote 58 Wagner also noted that younger banks tended to have higher capital ratios, whereas older banks tended to have lower ratios.Footnote 59 Bagehot made the same observation in the context of English joint-stock banking in the very same year.Footnote 60

Somary provided a further example of advancing views on capital adequacy in 1915, arguing that the amount of capital should depend on the duration of liabilities. Banks holding substantial amounts of short-term liabilities would require less capital. Comparing German and Swiss banks to their English counterparts, Somary noted that English banks did not engage in long-term lending, leading to lower capital ratios as compared to Germany and Switzerland.Footnote 61 Reflecting on Gilbart’s ‘one-third-requirement’ stipulated around ninety years earlier, Somary stated that such ratios were ‘unimaginable in present times’.Footnote 62

The experience of the United States concerning guidelines on capital ratios in the nineteenth century was very different to that in England, Germany, or Switzerland because capital was often regulated on the state or federal levels. Before the National Banking Act of 1864, banks were chartered by states; thus, rules varied according to the state. Many bank charters stipulated a minimum liabilities-(or debt)-to-capital ratio or, more narrowly, a notes-to-capital ratio. The purpose of such ratios – popular in practice and in banking theory – was to avoid the over-issue of banknotes in a system where many note-issuing banks existed. Tucker, for example, stated that ‘an over-issue of paper is one of the greatest mischiefs of banks’, adding that banks are ‘most strongly tempted by the desire of increasing their profits’. Limits on note issues in states often ranged between one and three times the capital.Footnote 63 Tucker argued that the idea of such a ratio was derived from the BoE’s old notes-to-specie ratio of 3:1.Footnote 64 Tucker provides a path-dependency argument, reasoning that the provision (‘the great rule of one third’) was transferred from England to the United States and then copied from one bank charter to another.

This argument is supported by a related discussion on the nature of capital at the time. Key debates centred around the form of capital that shareholders could pay in (specie or other forms, such as securities) and how that capital should be invested on the asset side (e.g. bills or government bonds). Many writers, such as McVickar, Lord, Gallatin, and Gouge, argued that capital banks should only invest their capital in very safe assets such as government bonds.Footnote 65

The National Banking Act of 1864 also set minimum capital requirements for national banks in absolute numbers. The Act made the amount of required capital dependent on the town population where the bank was located. The requirements were set at $50,000 for towns with a population of less than 6,000, $100,000 for towns with a population between 6,000 and 50,000, and $200,000 for larger towns. One-third of the capital of national banks had to be invested in US government bonds. The minimum capital requirements for state banks varied substantially, depending on state regulation. On average, these state-level requirements were lower than the capital requirements for national banks – in many cases, as low as $5,000. Some states also had no banking legislation at all. The varieties of capital requirements led to regulatory competition between states and between the state and federal levels.Footnote 66 As a result, the Gold Standard Act of 1900 decreased the minimum capital requirement for national banks from $50,000 to $25,000.

The root of linking capital requirements to a town’s population probably lies in several peculiarities of the US banking market. Branch banking was ruled out on the national level and almost non-existent on the state level. A geographic limit on the expansion of banks allowed tying capital requirements of banks to their location. A town’s size was likely considered a proxy for the extent of business conducted. The business activity, in turn, impacted the bills of exchange discounted at banks. Moreover, the total assets and liabilities grew or fell based on the discounted or matured bills of exchange.

As in other countries, discussions on capital requirements in the United States became more differentiated over time. By 1891, Dunbar, for example, had a well-developed view of the topic. He highlighted that there could be no rule for the minimum capital amount, as it should depend on ‘the extent of business’. The moment when ‘the business passes the line of safety’, requiring additional capital, however, should be determined independently by each bank.Footnote 67

Authors of nineteenth-century banking literature not only had an understanding of the relevance and role of capital but also of the relationship between capital and risk. Later contributions emphasised that assets with longer durations that could not be sold quickly would require higher capital ratios, as did assets with high potential losses. What did the literature reveal about the effect of a high capital/assets ratio on return on equity? Were trade-offs between these two ratios discussed?

Although the terms ‘leverage’, ‘return on equity’, and ‘capital/assets ratio’ were not used in the nineteenth century, contemporaries understood their meaning and their relationships. Instead of ‘return on equity’, bank managers would discuss the extent of dividends. In 1873, Bagehot commented on the leverage effect with the concise notion that ‘the main source of the profitableness of established banking is the smallness of the requisite capital’.Footnote 68

The discussion on the adequate relationship between ‘profitableness’ and ‘capital’ in nineteenth-century England usually materialised as a conflict of interest between shareholders and depositors. In 1834, Gilbart referred to the diverging interests of depositors and shareholders as the ‘evil’ of having ‘too small a capital’ and ‘too large a capital’ at the same time.Footnote 69 On the one hand, Gilbart emphasised the high potential losses of large banks in absolute terms. He also believed it would be alarming if banks paid dividends as high as 15% or 20%. On the other hand, he argued that capital might be used inefficiently in the case of abundance.Footnote 70 Joplin made similar considerations. The idea of capital being a guarantee for depositors was featured in almost all publications discussing capital. Moreover, contemporaries perceived adequate capital as a compromise between the capital’s role as a guarantee and the profitability of capital for the shareholders.

In the United States, deposits as a source of funding were (compared to England) less important during the first half of the nineteenth century. Measured against the balance sheet total, the share of deposits grew constantly. By 1834, deposits and banknotes each contributed about a quarter to the balance sheet total (the remaining half was contributed by capital). At the turn of the century, deposits made up about 80% (comparable to ratios of English joint-stock banks) of the balance sheet total, and banknotes became almost irrelevant (2%). A change in the banking literature discourse also reflected this structural change. Contemporaries became less concerned about the safety of banknote holders and more worried about the safety of depositors. Liquidity risks resulting from sudden withdrawals of deposits gradually received more attention.Footnote 71

3.2 England: Balancing the Interests of Shareholders and Depositors

The English banking market is unique as banking practitioners of the nineteenth century published frequently on the matter of banking. Did the decisions of bank managers regarding capital policy reflect the theoretical discourse? The London & Westminster Bank and the London and County Bank serve as examples of large and influential English joint-stock banks. The London & Westminster Bank was the first joint-stock bank established in London in 1834. Professional banking circles greeted the bank with hostility. Neither private banks, nor country banks, nor the BoE welcomed the establishment of a new competitor in London.Footnote 72 Two years later, in 1836, the London and County Bank was established as the Surrey, Kent and Sussex Banking Company in London (Southwark).Footnote 73

By the turn of the century, the two banks ranked third and sixth in size among the English joint-stock banks.Footnote 74 They merged in 1909 to form the London County & Westminster Bank. This amalgamation was the first among joint-stock banks of ‘the first magnitude’, creating the second largest joint-stock bank in England at the time.Footnote 75 Another merger took place with Parr’s Bank in 1918. By 1919, the then London County Westminster & Parr’s Bank was the third-largest bank in England, ranked in size after Lloyds and the London Joint City & Midland Bank.Footnote 76 In 1968, Westminster merged with the National Provincial Bank, becoming the National Westminster Bank.Footnote 77 The Royal Bank of Scotland took over National Westminster (NatWest) in 2000. The bank was renamed as the NatWest Group in 2020.

Two people who contributed substantially to the British banking literature were also crucial figures in establishing the London and County Bank and the London & Westminster Bank. Thomas Joplin, who had published essays on banking in 1822 and was a strong proponent of joint-stock banking, was involved in establishing the London and County Bank.Footnote 78 James William Gilbart became the first general manager of the London and Westminster Bank in 1833. He stayed in this position for twenty-seven years, shaping the bank’s evolution during its first decades.Footnote 79

There are several reasons for choosing these two banks for a closer analysis of capital ideas. As discussed, the two banks became influential joint-stock banks and were among the first large banks with roots in the early period of English joint-stock banking. Thus, their capital position can be traced from the early period of English joint-stock banking. Moreover, balance sheets and income statements are available from the beginning of their establishment. Banks did not have to publish assets and liabilities if they were established under the Country Banker’s Act of 1826 (as was the case for these two banks).Footnote 80 Nevertheless, the respective data is available, as well as being partly compiled and discussed by Theodor E. Gregory’s two-volume history of the Westminster Bank.Footnote 81 Finally, the limited data available for the English banking market also leaves no other option than to turn to individual banks. Aggregated data for the whole English banking market was only published after 1880.Footnote 82

3.2.1 Capital Structures at the Beginning of English Joint-Stock Banking: The Example of the Westminster Bank

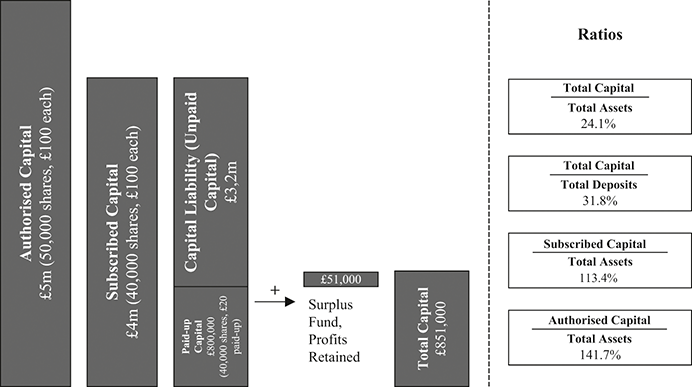

Figure 3.1 shows the capital structure of the London and Westminster Bank in 1844, ten years after the establishment of the bank. It serves as an example of capital structures in English joint-stock banking. Westminster had an authorised capital of £5m, split up into 50,000 shares of £100 each. By then, shareholders had subscribed £4m of the authorised capital. Of the subscribed capital of £4m, £800,000 was paid-up. The rest was capital liability. The total shareholder liability, however, was far greater than the capital liability because the bank operated under unlimited liability until 1880. Moreover, it must be noted that the London and Westminster Bank shares were not fully subscribed until 1847 – thirteen years after the bank’s foundation.Footnote 83

Figure 3.1 Capital structure of the London and Westminster Bank, 1844

The capital structure visualised in Figure 3.1 allows for the calculation of several ratios. Adding reserves and retained profits to the paid-up capital, one can calculate the total capital. Compared to total assets, capital stood at 24.1% (capital/assets ratio). The capital/deposits ratio was 31.8%. Total subscribed capital as a percentage of total assets was 113.4%. The dividends paid to shareholders were determined semi-annually and based on paid-up capital. In 1844, it was 6% of £800,000.

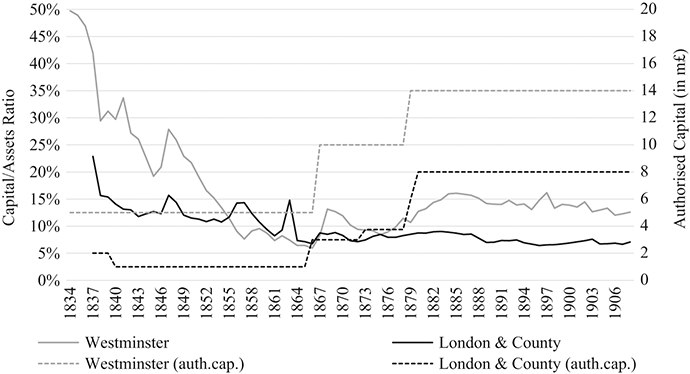

Figure 3.2 shows the capital/assets ratios (left axis) and the authorised capital (right axis) of the London and County Bank as well as the London and Westminster Bank from 1834 and 1837 to 1908. Both banks’ capital/assets ratios reached their low points in the 1860s. The authorised capital was raised substantially twice in the mid-1860s and in 1878.

Figure 3.2 Capital/assets ratios and authorised capital in million £, Westminster Bank (1834–1908) and London and County Bank (1837–1908)Footnote 84

The two banks increased their capital in various ways. Firstly, they could call up further instalments from their shareholders and raise the fraction that was paid-up. Secondly, they sold additional shares from authorised capital that was not yet fully subscribed, which increased the paid-up capital. Furthermore, the reserves grew if investors bought shares with a premium. Thirdly, the authorised capital could be raised, which required the consent of shareholders.

3.2.2 Large Capital as a Distinguishing Feature of the Early Joint-Stock Banks

The London and Westminster opened its doors in 1834 with an authorised nominal capital of £5m, of which £1.7m was subscribed by proprietors (shareholders) in the first year of business. The paid-up capital stood at £182,000, representing 49.7% of total assets – well within Gilbart’s ‘one-third-requirement’.Footnote 85 The London and County Bank started operating three years later with an authorised nominal capital of £2m, of which also only a fraction was subscribed in the first year. The bank started with a paid-up capital of £24,000, representing a capital/assets ratio of 22.9%.

The fact that both Westminster and London and County started operating without having their authorised shares fully subscribed by shareholders was not unusual. The Country Bankers Act of 1826 allowed the establishment of joint-stock banks for the first time outside a 65-mile radius of London, but banks continued to be mostly unregulated.Footnote 86 The Act did not introduce a charter requirement or set standards for the organisation or management of banks. There was no minimum nominal capital and no rule that a certain number of shares would have to be paid up before a bank started its operation. Theoretically, banks could have commenced business with no shares subscribed at all.Footnote 87 A ‘Secret Committee on Joint Stock Banks’, tasked by Parliament with analysing the effects of the 1826 Act in 1836, showed that only 15.8% of the nominal capital of English banks was paid up.Footnote 88 Setting the authorised capital very high and without any direct relation to expected business activities might have been done intentionally in many cases. On the one hand, it created an impression of ambition and high expectations for prospective shareholders. On the other hand, significant capital signalled strength to depositors.Footnote 89

Table 3.1 shows the total capital resources (authorised capital and reserves) as a percentage of total assets. In the 1840s, Westminster’s total capital resources were, on average, about 1.4 times the size of its balance sheet total.

Table 3.1 Total capital resources (authorised capital and resources) in percent of total assets, Westminster Bank and London and County Bank, averages per decade, 1841–1910Footnote 1

| Westminster | London and County | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Capital Resources/Total Assets | C/A Ratio | Total Capital Resources/Total Assets | C/A Ratio | |

| 1841−1850 | 137.8% | 24.8% | 77.5% | 12.9% |

| 1851−1860 | 54.0% | 12.0% | 25.1% | 11.7% |

| 1861−1870 | 35.3% | 8.8% | 17.0% | 8.8% |

| 1871−1880 | 39.7% | 10.0% | 19.1% | 8.0% |

| 1881−1890 | 53.1% | 14.9% | 25.4% | 8.3% |

| 1891−1900 | 50.2% | 14.2% | 20.2% | 6.9% |

| 1901−1910 | 47.2% | 12.1% | 18.8% | 7.0% |

1 Author’s calculations. Data: Gregory, Westminster Bank, Vol. 1; Gregory, Westminster Bank, Vol. 2.

Westminster’s capital/assets ratio remained above 20% until 1850 and was still roughly within Gilbart’s ‘one-third-requirement’. As Gilbart himself outlined, having significant capital was one of Westminster’s fundamental principles. The bank should be ‘prepared at all times for a withdrawal of its deposits – to be able to give adequate accommodation to its customers – and to support public confidence in seasons of extreme pressure’.Footnote 90

However, operating with a high capital ratio was also a way of distinguishing the legal form of the bank from private banks. Gilbart argued that private banks did not ‘carry on business with their own capital, but merely upon their credit’.Footnote 91 As Westminster stressed in its first prospectus for potential shareholders, the capital was one of the main advantages of joint-stock banks compared to private banks.Footnote 92 The future bank promoted that it should be established ‘with such an extent of Capital as will ensure the perfect confidence and security of depositors, and the greatest practical accommodation and assistance to trade and commerce’.Footnote 93

3.2.3 Conflicting Interests: Shareholders versus Depositors

In the years after the foundation of the Westminster Bank, its chairmen frequently justified capital increases as a way to foster public confidence – and, more specifically, depositors’ confidence.Footnote 94 The bank was anxious to balance the interests of both shareholders and depositors. When shareholders questioned the increases of the reserve fund at general meetings, the board argued that no one should be able to accuse the bank of not augmenting the reserves ‘whilst it went on increasing its dividends’.Footnote 95

Similarly, in 1862, the Westminster Bank maintained that it wanted to pay high dividends but also emphasised that extensive reserves were required as a sign of ‘prudence and safety’ for depositors.Footnote 96 Five years later, the bank urged its shareholders once again to increase the capital, arguing that depositors should be offered more than the existing capital ‘as an immediate security for the payment of their liabilities’. However, the bank promised to make the capital increase ‘as advantageous as possible for the shareholders’.Footnote 97

The London and County Bank used a similar line of argumentation to justify capital increases to its shareholders. By 1857, the bank had capital and reserves of £600,000 on its balance sheet. Their capital/assets ratio was 14.3%. At the annual meeting in 1857, London and County’s chairman stated that the paid-up capital invested in the bank should be of ‘fair proportion’ and that this capital would have ‘to carry the weight of the customers’ balances’.Footnote 98 In 1862, another substantial increase of capital was necessary, according to the chairman of London and County, in order ‘to be in the front rank of joint-stock banks’.Footnote 99 The chairman argued that the bank’s growth, primarily driven by advances to railway companies, should not be financed with customers’ deposits. At the same time, the chairman replied to criticism from the shareholders by emphasising that additional capital now would mean they would need to add less to the reserve fund in the future. Hence, London and County could share all its profits with the shareholders.Footnote 100

As London and County raised additional capital in 1872, the chairman once again maintained that the relation of capital and reserves to liabilities should be ‘fair’.Footnote 101 But how much did London and County’s chairman consider to be fair or adequate? He referred to a target ratio of capital to liabilities of 10%.Footnote 102 Moreover, he commented that London and County had increased its capital in past years if the capital/liability ratio fell below 7%, and additional capital was necessary to ‘keep up our position’ compared to competitors.Footnote 103

Compared to other large joint-stock banks, London and County’s capital ratio (7.15%) was among the lowest. In 1872, Westminster had a capital/assets ratio of 9.4%, National Provincial had a ratio of 8.1%, and the London Joint Stock Bank had 8.2%. With that in mind, the chairman of London and County confirmed once again that a 10% ratio was considered a ‘fair proportion’ in 1873.Footnote 104 However, such ratios represented a significant shift in ideas among English banks, who had moved away from the initial idea of the 1820s and 1830s that joint-stock banks would need substantially high capital to distinguish themselves from private banks.

3.2.4 The City of Glasgow Shock

Despite frequent references to the importance of a high capital/liability ratio in gaining the trust of depositors, the capital/assets ratios of major English joint-stock banks had been falling since their establishment in the 1830s. The collapse of the City of Glasgow Bank in 1878 was a temporary turning point for the trend towards lower capital ratios. The reversal of the trend, however, did not last long.

Like most other banks at the time, the City of Glasgow Bank operated under unlimited liability, and its failure led to the bankruptcy of most of the shareholders.Footnote 105 Even though banks could register with limited liability from 1857 onwards, most banks continued to operate with unlimited liability until 1878, as unlimited liability was often seen as an essential guarantee for depositors.Footnote 106 Not surprisingly, contemporaries expected substantially higher capital ratios, as higher capital levels would replace unlimited liability. In an article titled ‘The Great Addition About to Be Made to the Capital Employed in Banking Enterprise’, The Bankers’ Magazine argued that the ratio of capital to liabilities would be ‘altered materially’ with the introduction of limited liability. In fact, The Bankers’ Magazine estimated that the new average capital/liability ratio would stand around 20%.Footnote 107

Indeed, both Westminster and London and County increased their authorised capital in 1878. The two banks justified the increases as additional security needed for their depositors. Having abandoned unlimited liability, they did not want their stability to be questioned by customers.Footnote 108 At the same time – once again – the banks tried to find a ‘good middle course as between the interests of the shareholders and the customers’.Footnote 109

Besides Westminster and London and County, the National Provincial Bank also changed to limited liability and increased its capital. Lloyds and Midland, were already operating with limited liability before 1878 and did not issue additional capital. This behaviour is not surprising. Turner analysed a broader sample of sixty-three English banks for 1874 when some banks were already on limited liability and others were not. Turner shows that limited liability banks had higher capital ratios than those with unlimited liability in 1874.Footnote 110

Turner provides a valuable contribution to the debate surrounding shareholder liability in British banking, highlighting that the debates focused on the credibility of unlimited liability regimes and the question of how depositors could be assured of bank safety once a bank changed from unlimited to limited liability.Footnote 111 He shows that William Clay, a member of Parliament from 1832 to 1857, had already outlined the relevant issues for discussing unlimited and limited liability in 1836. Clay argued that the change to limited liability would require forms of assurances to depositors concerning banking stability. The issues outlined by Clay were later discussed by banking experts, most notably Walter Bagehot and George Rae.Footnote 112 Resulting from this debate, the reserve liability was included in the Company Law in 1879.Footnote 113

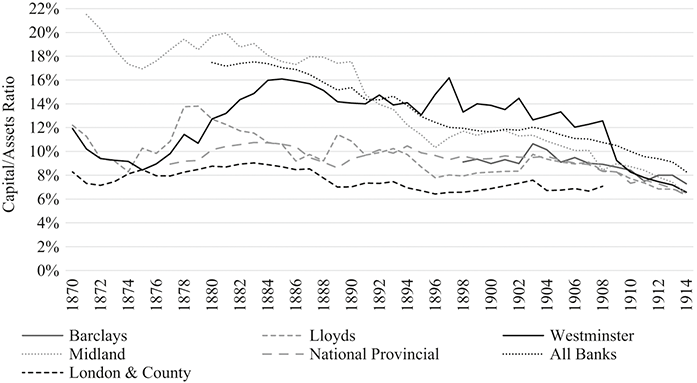

Figure 3.3 shows the capital/assets ratios of six joint-stock banks and the average ratio of all joint-stock banks from 1870 to 1914. By 1880, the capital/assets ratio stood at 17.5%. This level was considered the new standard by The Bankers’ Magazine after eliminating unlimited liability. The new standard, however, deteriorated quickly. At the turn of the century, the capital/assets ratio stood at 11.6%. From 1880 to 1913, the capital/assets ratios of English joint-stock banks fell by 8.6pp.

Figure 3.3 Capital/assets ratios, 1870–1914Footnote 114

3.2.5 The Twentieth Century View on Capital: Shareholders’ Interests Prevail

After the failure of the City of Glasgow Bank, the public and bank managers viewed recapitalisations as a necessity to maintain public confidence. Conversely, having too much capital was disparaged at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Once again, Westminster proves to be a case in point. The capital/assets ratio of the Westminster Bank was above the average of English joint-stock banks between 1895 and 1908 and was substantially higher than the ratio of any of its competitors shown in Figure 3.3. This high capitalisation was considered a problem at the Westminster Bank for many years.Footnote 115 Beyond the capitalisation itself, the structure of their capital was also viewed as problematic. Westminster’s paid-up capital was twice as big as its reserves. Most other banks had reserves almost exceeding the paid-up capital. Consequently, given the high capital ratio, Westminster struggled to pay dividends as high as its competitors. And not only was the capital ratio high, but the proportion of paid-up capital within the company’s total capital was considered high too.Footnote 116

Westminster saw the merger with the London and County Bank in 1908 as a solution to that problem. At the extraordinary general meeting in 1908, Westminster’s chairman Walter Leaf presented the bank’s capital/liability ratio as one of the main reasons for the merger. Referring to Westminster’s capital/liability ratio of 11% in 1907, Leaf argued that the ratio of London and County was below 5%, ‘and it certainly could not be said that the larger figure [Westminster’s] was necessary for the credit of their company’.Footnote 117 In a similar vein, The Bankers’ Magazine commented that Westminster’s capital was ‘out of proportion’ and that it would have been difficult to adjust the ratio if not through an amalgamation.Footnote 118 In contrast to previous discussions on the adequacy of the level of capital, neither the interests of depositors nor their confidence in the bank seemed to be of major importance anymore. Instead, Leaf remarked that their shareholders would be ‘better protected by a reduced liability’.Footnote 119

The newly established London County and Westminster Bank had a paid-up capital of £3.5m and reserves of £4.25m. London County and Westminster’s capital/assets ratio stood at 9.2%, 3.3pp below the ratio of Westminster before the merger. With that, the capital structure of the ‘new’ Westminster converged towards that of its peers (see Figure 3.3).

Contemporary banking literature provides essential insights into the management of banks and their capital structure. Conflicting interests between shareholders and depositors with regard to the level of capital were frequently discussed in this literature. It was also a central topic within the management of English joint-stock banks from their emergence in the 1820s to the beginning of the twentieth century. At the beginning of English joint-stock banking, having significant capital seemed important. Furthermore, target capital ratios – such as Gilbart’s ‘one-third-requirement’ – were used. The Westminster Bank seemed to follow that guideline until the 1850s. The London and County Bank communicated a capital/liability target ratio of 10% in the 1870s, which was probably the convention for joint-stock banks at the time. Capital considerations became more nuanced in subsequent years, stressing the required balance between shareholders’ and depositors’ interests. After the turn of the century, shareholders’ interest in low capitalisation and high dividend payments seem to have prevailed, leading to even lower capital/assets ratios.

3.3 Switzerland: Transparency in the Absence of Regulation

In the nineteenth century, many big Swiss banks publicly discussed their capital levels. The following analysis focuses mainly on Credit Suisse. Where possible, the discussion of capital adequacy is broadened to the whole group of big banks. However, in the absence of statutory accounting and publication standards, the availability of data and information remains fragmented.Footnote 120

Founded in 1856 as ‘Schweizerische Kreditanstalt’, Credit Suisse is one of the oldest banks among the group of big banks. Credit Suisse was the most transparent bank during the nineteenth century, providing comprehensive information on the state of their business and regularly discussing reasons for changes in the capital structure. Credit Suisse has been ranked among the biggest banks in terms of total assets during its entire lifespan.Footnote 121 The bank gained considerable importance via financing railway projects and industrial finance during the last third of the nineteenth century.Footnote 122

Credit Suisse was founded with a nominal capital of CHF 30m, of which CHF 15 m was paid-up. Shareholders were not liable beyond the nominal capital.Footnote 123 The bank publicly discussed capital adequacy for the first time when it issued additional stocks of a nominal CHF 5 m in 1873. The issuance of new capital brought its capital/assets ratio back to the 30% level after it had fallen below that threshold two years earlier. Credit Suisse justified the issuance by referring to increasing business activities in Switzerland and abroad.Footnote 124 It has been stated that Credit Suisse profited from the strong economic activity in Switzerland, especially after the Treaty of Versailles in 1871.Footnote 125 Credit Suisse’s board of directors emphasised the bank’s international expansion and expectations of counterparties in foreign transactions.Footnote 126

Credit Suisse issued additional capital in 1889 and 1897. The stock issuance in 1889 again led to an increase in the capital/assets ratio from 22.3% to 30.4%. Similarly, the issuance of additional capital in 1897 lifted the percentage from 25.9% to 34.1%.

The bank’s 1889 annual report cited the findings of an internal study on the ‘question of the equity capital increase’. This is the most extensive public elaboration by the bank on why it required additional capital. Credit Suisse’s Board of Directors argued in favour of higher equity capital by mentioning the fast balance sheet expansion, the proportion of equity capital to liabilities, the risk of potential losses arising from accounts due from customers without collateral, the expected strong demand for credit as a result of an increase in business activities in the past, and the high (and increasing) dividend performances in the past for its investors. The bank also communicated that it wanted to return to the capital ratio it maintained after its last stock issuance in 1873.Footnote 127 This shows that Credit Suisse was aiming for a capital/assets ratio of around 30%, for which it issued new stocks.

These arguments were not uncommon among the big banks. The Swiss Bank Corporation (SBC) issued additional capital in the same years, highlighting the rapid total assets growth and the importance of its reputation. Moreover, the SBC’s directors believed that customers could perceive other banks as serious competitors due to their high capital ratios. Thus, the bank would require more capital to keep its standing. In terms of its investors, the SBC assured them that the fresh capital was just the minimum needed for the bank’s development and that the amount would ensure stable dividends in the future.Footnote 128

In 1905, Credit Suisse commented on another stock issuance in its annual report, providing two arguments for raising its capital. Firstly, Credit Suisse was taking over the ‘Bank in Zurich’ and the ‘Oberrheinische Bank’ in Basel and needed new shares for a share swap with existing shareholders.Footnote 129 Takeovers of other banks were an often-used reason for capital issuances among the big banks.Footnote 130 Secondly, the bank once again stressed that the capital/liability ratio should not fall below a ‘certain’ level. The board of directors suggested a ratio of 1:3 (capital/liability ratio: 33%; capital/assets ratio: 25%) and emphasised that such a ratio would still allow for achieving an ‘adequate’ return for its shareholders:

The development of our institution during the last eight years was positive; it is however also an obligation, that given the risks of our business operation as a trading and financing institute, we need to make sure that the capital strength of our bank does not fall below a certain ratio as compared to the debt capital. Even though the current ratio of about 1:3 is not inappropriate, it seems to us that the requested increase of our capital is in the interest of the reputation, the credit and the productivity of our institute. Even with the capital increase, we believe we can communicate the expectation that we will be able to provide appropriate returns, which will not be below previous returns.Footnote 131

After a capital increase in 1904, the leverage ratio grew to 25.3%. The bank increased its capital again in 1906. As on earlier occasions, Credit Suisse assured its investors that it would pay stable dividends in the future. However, Credit Suisse seemed to abandon its target capital ratio in the years leading up to the First World War; 1905 marked the last year the bank made a specific statement on the size of capital it aimed to maintain. From 1905 to 1914, capital/assets ratios decreased from 25.3% to 19.2%. The bank did not issue new shares until 1912, and only then as a result of the takeover of two banks.

A changing view on capital adequacy in later years was further demonstrated by Credit Suisse’s capital increase in 1927. The bank refrained from mentioning specific ratios or discussing the capital situation in more detail. Instead, the bank only remarked in rather general terms that its own capital and the debt capital should be in a ‘healthy proportion’ to each other.Footnote 132

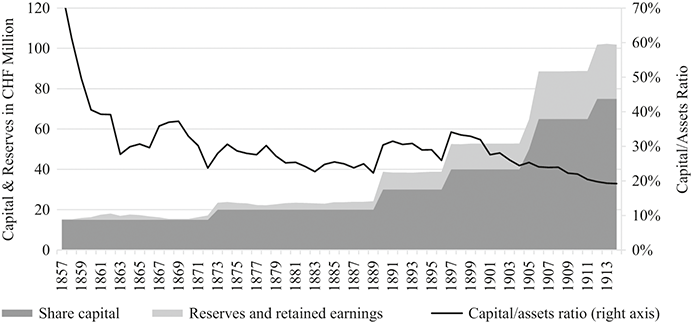

Figure 3.4 shows Credit Suisse’s capital/assets ratio as well as the total capital and reserves from 1857 to 1914. Until 1905, the bank issued new shares four times, usually when the capital/assets ratio fell below the 20% or 25% threshold. What is also apparent from Figure 3.4 is the importance of capital issuances not only for increasing the share capital but also for increasing the reserves. The premium between the nominal value and the share price was attributed to the reserves. During this period, it was mainly the premium on capital increases that led to growing reserves and not retained profits.

Figure 3.4 Share capital, reserves, and the capital/assets ratio of Credit Suisse, 1857–1914Footnote 133

3.3.1 Swiss Banking Practice and the Role of ‘Rules of Thumb’

The ‘1:3-rule’ that was applied in Swiss banking practice was also promoted by James William Gilbart’s A Practical Treatise on Banking, published in 1827. However, the Westminster Bank, of which Gilbart was the general manager from 1833 to 1860, abandoned that guideline in the 1850s. Did all Swiss banks nonetheless follow Gilbart’s rule of thumb until the late nineteenth century, as the case of Credit Suisse would suggest?

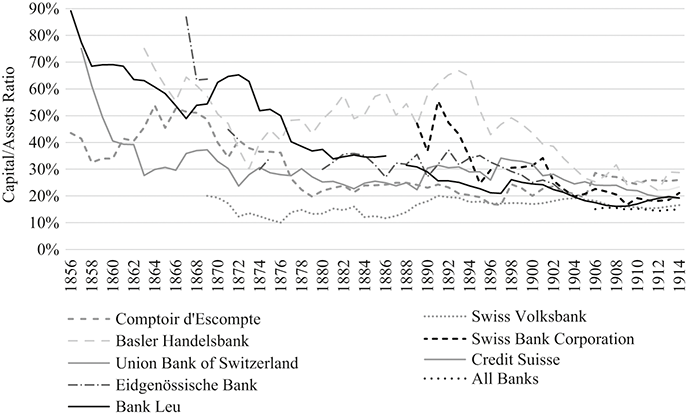

It cannot be said that all Swiss banks followed Gilbart’s principle. Most of the large joint-stock banks did, however, maintain capital/assets ratios above 20% until the end of the nineteenth century. Figure 3.5 shows the capital/asset ratios of the big banks from their establishment until 1914. The significant decreases in capital ratios at the beginning of the time series were because the founders were often ambitious regarding their business growth. Thus, capital ratios ‘normalised’ over time once a bank started making investments, granting loans, and attracting liabilities. As the banks grew, their capital/assets ratios fluctuated between 20% and 40%.

Figure 3.5 Capital/assets ratios, big banks, Switzerland, 1856–1914Footnote 134

Until the 1940s, the big banks had considerably higher capital ratios than other bank groups in Switzerland. By 1914, the average capital/assets ratio of the big banks stood at 20.1%. Cantonal banks had a capital/assets ratio of 12.1% and Raiffeisen banks a ratio of 3.3%. In earlier years, this discrepancy was even more prominent. Consequently, if Gilbart’s ideas regarding capital (capital/liability ratio of 1:3) were present in Switzerland, only one group of banks had adopted them. All other groups would have disregarded it, which is unlikely.

3.3.2 The Business Models of the big banks

What else explains the big banks’ persistently high capital/assets ratios? The answer lies in the business models of the big banks and how the banks themselves perceived the risks associated with their business. Credit Suisse referred to the riskiness of its business operations as an argument in favour of a high capital ratio, maintaining that the high risks required more capital. What exactly did this mean? Big banks such as Credit Suisse and SBC offered a variety of banking services for industrial and commercial companies, leading to a high loan exposure and often also to securities investments on the asset side. Engaging in business activities bearing high risk would require more capital. Other banking groups, such as regional, savings, Raiffeisen, and cantonal banks, focused mainly on deposits and mortgages for private customers. The mortgage business was considered less risky.Footnote 135

Table 3.2 provides insights into the asset structure of the big banks in 1870, 1880, 1890, 1900, and 1910. At the time, investing in securities and providing unsecured commercial loans were two key pillars of the big banks’ business. The table presents these two asset items as a percentage of total assets.

Table 3.2 Share of securities and unsecured loans in percent of total assets, big banks, 1870–1910Footnote 1

| 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Securities | 13.9% | 11.9% | 10.2% | 8.0% | 8.7% |

| Unsecured loans | n.a. | 21.5% | 23.0% | 24.0% | 16.9% |

1 Author’s calculations. Data: Individual Annual Reports. Notes: The following banks are missing for 1870: Swiss Bank Corporation (SBC), Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS), Comptoir d’Escompte de Genève (CEG), Bank Leu. Missing for 1880: UBS and CEG. Missing for 1890 and 1900: UBS. Data on unsecured loans is only available from Credit Suisse, SBC, and Bank Leu.

The share of unsecured loans to commercial customers fluctuated between 16.9% and 24.0%. It seems that the amount of unsecured loans as a percentage of total assets dropped at the beginning of the twentieth century. Similar to the unsecured loans, the share invested in securities also fell over time. By 1910, banks were investing 8.7% of their assets in securities on average. In 1870, the percentage had stood at 13.9%.

One might also ask how well-diversified the securities portfolios were. There was a high sectoral dependence on investments in railway companies. In the case of Credit Suisse, for example, around 40–60% of the stocks held between 1870 and 1910 were in railway companies. The largest amount was invested in the ‘Nordostbahn’.Footnote 136 The ‘Nordostbahn’ was run by Alfred Escher, who was also the president of the board of Credit Suisse.Footnote 137 Credit Suisse also invested in a variety of foreign securities. Overall, the bank followed a somewhat speculative business model until the 1880s.Footnote 138

The lower shares of securities and unsecured loans in the balance sheets in 1910 indicate that banks had reduced the risks of their assets, which would allow for a lower capital ratio. Furthermore, another emerging business model among the big banks impacted the composition of their securities portfolio when they, together with the cantonal banks, established a monopoly in issuing government securities.

The underwriting business of the big banks had been growing since their establishment. In 1897, Credit Suisse started a cartel with the SBC and the Union Financière de Genève. More banks joined in the following years, forming the ‘cartel of the big banks’.Footnote 139 The cartel contract stated that all government bond issues of more than CHF 2 m that a cartel member handled had to be forwarded to the cartel. The cartel members then shared the placement and its profits.Footnote 140 The power of the big banks grew further when their cartel joined forces with the Association of Cantonal Banks in 1911. Government financing on the federal and cantonal levels, as well as the emission of bonds for the by then nationalised Swiss railway, became impossible without the support of the big banks and the cantonal banks.Footnote 141 Some of these securities were kept in the banks’ balance sheets. The available data in the annual reports of the big banks indicates that the share of government bonds increased slightly in the years before the First World War.

Overall, three effects had altered the business models of the big banks by 1914. Firstly, the big banks had reduced the share of unsecured loans. Secondly, the share of securities had decreased. Thirdly, the banks had engaged in the underwriting business. These three changes lowered the overall risks of the banks and their balance sheets and might have justified lower capital ratios.

The perception of what amount of capital should be considered adequate has changed over time. Banks followed specific benchmarks of about 25% until the late nineteenth century. Most large joint-stock banks in Switzerland showed similar behaviour, as they frequently issued new stocks to restore their target capital/assets ratio. This behaviour seems to have changed during the decade leading up to the First World War, when capital issuances became less frequent. The riskiness of their business was an often-cited reason for issuing fresh capital, and banks compared their standing with that of their competitors. Yet the variation of the capital ratios decreased over time. Stable dividends for investors were given high importance in the statements made by banks, which is unsurprising given that investors had to approve capital issuances. The trade-off that defined an adequate capital ratio for the Swiss big banks was usually one between the risk of the business model and shareholders’ interests.

3.4 United States: Capital Requirements From the Very Beginning

The US banking market offers numerous examples for analysing the foundation of banks and their capital policies. Compared to the evolution of banking in the United Kingdom and Switzerland, the development of banking in the United States was turbulent. Striking features of the US banking market were frequent crises, a high number of small banking units, many market entries and exits, varying regulatory regimes (on the federal and state levels), several supervisory agencies, and – in the context of capital policies, the most relevant difference – the right to issue banknotes.

The period leading up to the twentieth century in US banking can be broadly divided into three periods: the early years of American banking until 1837, the era known as free banking from 1837 to 1863, and the national banking era from 1863 to 1913.Footnote 142 Different regulatory and supervisory systems and agencies emerged during these periods, which also had implications for regulating capital in banking.

Banking regulation and supervision were left to the individual states throughout the free banking period. Banks could obtain a charter and enter the market freely if they could raise a certain amount of capital. Bank regulation and supervision varied according to the different states. The national banking period covers the period from the establishment of nationally chartered banks to the creation of the Federal Reserve (FED). The Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 provided the regulatory framework for that period and led to the emergence of the first federal banking supervisory agency: the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). Among the OCC’s tasks were the chartering and supervision of national banks. From 1913, the OCC shared its supervisory responsibility for national banks with the FED. Additionally, the FED had supervisory authority over state banks that chose to become members of the Federal Reserve System. A third federal bank supervisory agency finally emerged in 1934. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was charged with administering the deposit insurance programme and had supervisory authority over national banks and state banks that opted for federal deposit insurance.

The first commercial banks in the United States and the leading banks from New York City serve as examples of capital policies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Given the fragmentation of the US banking market, the domestic relevance of the New York City–based banks measured by market shares, for example, cannot be compared to that of the large banks in England or Switzerland. However, the prominent banks of New York took central importance in the US banking market. They were located in the country’s leading financial centre, were among the largest banks in the country, and were of vital relevance as much of the reserves of banks in the United States were placed in New York City banks.

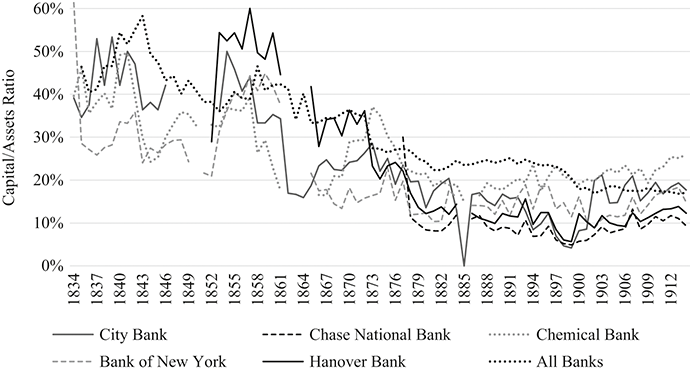

Figure 3.6 shows the capital/assets ratios of five prominent New York City banks from 1834 to 1914: The Bank of New York (founded 1784, now commonly known as BNY Mellon), City Bank (1812, now Citigroup), Chase National Bank (1877, now JP Morgan Chase), as well as the Chemical Bank (1823), and Hanover Bank (1873), which both became part of JP Morgan Chase over time.

Figure 3.6 Capital/assets ratios, selected banks in New York City, 1834–1914Footnote 143

The capital/assets ratios of the five New York banks remained above the 20% threshold for most of the time until the 1870s and ranged roughly between 10% and 20% throughout the following years leading up to 1914. Compared to all banks in the United States, the five banks tended to have lower capital/assets ratios.

3.4.1 How to Get Something for Nothing: The Dubious Quality of Capital in the Early US Banking Period

The United States’ first commercial banks were already founded by the 1780s. The Bank of North America was established in 1781, the Bank of Massachusetts and the Bank of New York in 1784. Following Alexander Hamilton’s initiative (the first secretary of the US treasury), the federal government made its first steps towards central banking in 1791 with the creation of the Bank of the United States, known as the First Bank of the United States. The First Bank of the United States was also active as a commercial bank, accepting deposits and providing loans to the public. It operated until 1811 and was succeeded by the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. The Charter of the Second Bank ended in 1836, initiating the free banking era.

Bank capital was an essential concern in all of these new banking establishments, and was often of dubious quality. Similar to English joint-stock banks, a feature of US banking was that the authorised capital stipulated in the bank charter deviated strongly from the paid-up capital. Raising capital for a bank was a gradual process in which shareholders subscribed capital in several instalments. A case in point is the First Bank of the United States, with an authorised capital of $10m, of which the federal government subscribed $2m. As Hamilton realised that it was impossible to fund such an amount with specie (gold or silver) in a period where precious metals were scarce, the charter stipulated that only one-fourth of the remaining $8m had to be paid in specie. Shareholders could pay the remaining $6m with government securities.Footnote 144

After the first instalment by the shareholders, the First Bank of the United States started operating with only $400,000 paid up. As the federal government could not provide $2m for its subscribed shares, the bank, now able to create money, provided a loan to the government at an interest rate of 6%. The government used the loan to pay for the shares, for which it then received dividends from the bank.Footnote 145

A build-up of capital through several instalments of shareholders and a substantial deviation between authorised and actual capital was representative of many bank foundations that followed. Banks often started operating after one instalment, representing as little as 5% to 15% of the authorised capital. A second issue frequently criticised by contemporaries concerned banks’ lack of specie money. In many cases, the foundation of later banks with a lower standing involved speculative schemes. Shareholders used the shares they received after the first instalment as collateral for a loan from the same bank. They then paid for the second instalment with the money received from the bank as a loan.Footnote 146 It was essentially a bet by shareholders on the bank’s survival and ability to pay a dividend above the loan’s interest rate or, in William Gouge’s words, ‘hocus-pocus’.Footnote 147 The use of bank loans for buying additional stock was widespread, and some states passed laws prohibiting or at least limiting the practice from the late 1820s. Overall, banking provisions became stricter towards the end of the free banking era.Footnote 148

3.4.2 The First Capital Adequacy Ratios: Limiting Note Issuance

The Bank of New York (founded in 1784) and one of its founding fathers, Alexander Hamilton, took a less speculative stance on banking policy. During the first seven years of its existence, the bank operated without a charter, and its owners were subject to unlimited liability. The paid-up capital was $500,000. The Bank of New York received its charter from the State of New York after several attempts in 1791. By then, New York was only the second state in the United States to charter a bank, and the bank charter also constituted a first step towards banking provisions.

The 1791 Bank of New York charter stipulated a capital of $900,000, but, more importantly, it also introduced a formal debt/capital ratio to control the note issuance. The charter limited the amount of debt to a maximum of three times the capital subscribed.Footnote 149 The debt/capital ratio of 1:3 in 1791 – or a capital/debt ratio of one-third – was probably one of the first capital adequacy rules in the United States.Footnote 150

As noted earlier, the idea for limiting note issuance likely originated from old note-issuing banks in Europe.Footnote 151 The charter of the First Bank of the United States in 1791 included – indirectly – a note-issue limitation too. The amount of debt was not to exceed the bank’s authorised capital of $10m.Footnote 152 A similar 1:1 ratio was applied to the Second Bank of the United States, limiting the amount of debt to the bank’s capital of $35m.Footnote 153

The charter of the Bank of New York served as a blueprint for many subsequent bank charters, and the limitation of note issue was a frequent charter provision.Footnote 154 Limiting the debt – or, more narrowly, note-issue – to bank capital became a standard rule in US state banking until the Civil War. The requirements varied across states and became stricter between the 1830s and the 1860s.Footnote 155 During the national banking era, the note issue was regulated, too: The National Banking Acts of 1863 and 1864 limited note issues to a national bank’s capital stock.Footnote 156

While such limits probably avoided the over-issue of notes in individual cases and in the early banking period in the United States, they had little effect on the average national bank during the national banking era. The total banknote volume never grew close to the capital stock of national banks between 1863 and 1914. The banknotes-to-capital ratio was about 60% on average in the respective period – far from reaching the 1:1 limit.Footnote 157 Thus, the amount of capital was not a limiting factor for most of the national banks.

3.4.3 Building Up Capital Through Retained Earnings