1.1 Chaucer’s Japes

One of the most prominent markers of Chaucer’s elevation as a subject of historical inquiry was the philological attention accorded to his language by early modern readers. Nestled in the glossary of old and obscure words accompanying Thomas Speght’s 1602 edition of the Workes is a textual curio which brings contemporary concerns with Chaucer’s language to the fore. Written in rhyming couplets, the tale is included as part of the glossary’s first entry under the letter I and details an extraordinary encounter between a medieval book and an early modern reader:

Jape, (prolog.) Jest, a word by abuse growen odious, and therfore by a certain curious gentlewoman scraped out in her Chaucer: whereupon her seruing man writeth thus:

In Chaucer’s Middle English, a jape is a trick or a frivolity, or the act of conducting one; the Parson uses it as a synonym for a trifling tale.Footnote 2 But by Speght’s time, jape had expanded its semantic range to include seduction and other sexual acts.Footnote 3 That the old word had ‘growen odious’ is attested by various knowing allusions to Chaucer’s jests in the late sixteenth century. The offending party in this story, however, is not Chaucer’s language but the uninformed reader herself, whose feigned modesty results in her erasure of the poet’s harmless words. Her servant, to whom Speght attributes the verses, is quick to mock his mistress’s prudish sensibilities. The anecdote’s wit relies on this tension between women’s linguistic restraint and sexual licentiousness. It singles out hypocritical female readers who censor and alter Chaucer’s words although they ‘[love] the sence’, and the joke, such as it is, is ultimately on them.

Elizabethan writers, too, exploited the semantic slipperiness of Chaucer’s old word jape (and its related euphemisms) for comedic ends. Misodiaboles, the pseudonymous author of the pamphlet Ulisses upon Ajax (1596), invokes the two distinct types of Chaucerian jest in his pithy description of a certain married gentlewoman who unsuccessfully tries to seduce a tenant farmer: ‘A pleasant wench of the country (who besides Chaucers jest, had a great felicitie in jesting)’.Footnote 4 The anonymous university play The Returne from Parnassus I (1597) presents a more extended joke on this theme. In one scene, the scholar Ingenioso tries to impress the foolish patron Gullio with his ability to compose poetry in the Chaucerian, Spenserian, and Shakespearean styles.Footnote 5 The patron Gullio requests a Chaucerian-style composition for his mistress: ‘Lett me heare Chaucer’s vaine firste. I love / Antiquitie, if it be not harsh’. Ingenioso duly delivers three stanzas of Middle English pastiche modelled on Troilus and Criseyde, which quickly descend into mockery: ‘For if a painter a pike woulde painte / With asse’s feet and headed like an ape, It corded not; sow were it but a jape’. Gullio interjects to express his displeasure at the unusual composition:

Gull.

Ingen.

Gull.

This trio of examples attributing to Chaucer the word jape and the euphemised jest – in Speght’s edition, a pamphlet, and an academic play – date from the late Elizabethan period, when the Middle English language was becoming increasingly difficult for contemporary readers to understand. Strikingly, each story harnesses the suggestive ambiguity of Chaucer’s English to gesture playfully towards the female sexual appetite. The three women described by the serving man, Misodiaboles, and Gullio respectively might diverge in their reactions to japing as word or deed, but the possibility of female licentiousness lurks in the background of each account. Whether the case of the censorious gentlewoman in Speght, the ‘wench of the country’, or Gullio’s supposedly chaste mistress, each anecdote excavates the transgressive potential of Chaucer’s language to set up familiar tropes about women’s sexual modesty or immodesty. Such jokes revel in their use of what was, for the Elizabethans, an explicit word.Footnote 7 But if Chaucer’s language provided comic fodder for some writers, it proved a more serious problem for his proponents, who harboured the pervasive worry that archaic language was prone to ambiguity and miscommunication.

It is a problem raised by George Puttenham in his Arte of English Poesie (1589), during his discussion of the Greek Cacemphaton or ‘figure of foule speech’. Puttenham highlights cases ‘when we vse such wordes as may be drawen to vnshamefast sence, as one that would say to a young woman, I pray you let me iape with you, which in deed is no more but let me sport with you’. Although such figures are ‘in some cases tollerable, and chiefly to the intent to mooue laughter, and to make sport, or to giue it some prety strange grace’, he cautions that ‘the very sounding of the word were not commendable … For it may be taken in another peruerser sence by that sorte of persons that heare it’.Footnote 8 This rhetorical figure may legitimately serve a ludic purpose, but such words may also be misinterpreted or ‘drawen to vnshamefast sence’ by others. Thomas Middleton’s No Wit/ Help Like a Woman’s (1611), too, makes a point about the challenge of preserving female modesty amidst linguistic instability and change when one character wonders, ‘How many honest words have suffered corruption since Chaucer’s days? A virgin would speak those words then that a very midwife would blush to hear new’.Footnote 9

Speght’s Workes was well aware of this capacity of words to slide between propriety and offensiveness. A recent essay by Daniel J. Ransom which investigates Speght’s use of jape in the 1598 and 1602 texts shows that the editor appears, for a time, to have opted for the less offensive emendation yape so as ‘to make a visually and aurally clear distinction between the disreputable word and the word as Chaucer used it’.Footnote 10 The anecdote about the serving man’s mistress which he prints likewise tries to rein in faulty interpretations, assuring readers that the true meaning of jape, ‘as Chaucer ment’, was nothing more than a jest, a joke, or a gibe.Footnote 11 By including the rhyme about the curious gentlewoman, Speght’s wider point is a self-congratulatory one: reading Chaucer with his glossary, then the most extensive key to Middle English ever printed, prevents readers from making embarrassing mistakes and assumptions about what ‘Chaucer ment’.

Speght’s glossary offered a tidy solution to such problems of reading Chaucer’s difficult words, but it does not fully account for readers like the serving man’s offended mistress. As a reader who takes to the writing surface to ‘scrape out’ the odious word, she is more likely to have read her Chaucer not in a printed edition of Speght, but in an early manuscript whose parchment leaves would better tolerate the erasure here described. We might imagine her reading Chaucer in an old, scribally copied book and, lacking the apparatus handily furnished in Speght’s edition, or a sufficient knowledge of Chaucer’s Middle English, taking knife to parchment skin to remove it.

This vignette may preserve nothing more than a story invented for humorous effect, and we need not accept Speght’s account that a serving man really wrote these verses, or indeed the verses’ own tale of a female reader rubbing rude words out of a manuscript. What is clear is that this fictional reader had real early modern counterparts who continued to read Chaucer in manuscript, and who form the subject of this book. The evidence in surviving copies, which this chapter presents, affirms the willingness of such readers to gloss, correct, and emend Chaucer’s Middle English as they found it. Their myriad interventions on the page – in the form of erasure, crossing out, overwriting, and additions – document the commitment of early modern readers to improving and updating the version of Chaucer’s language that survived in older manuscript books. Alongside energetic Renaissance debates about literary archaism and the perils of old-fashioned ‘Chaucerisms’, readers wondered about the meaning of this language and the accuracy of the books that preserved it. The textual and philological attention that early modern readers accorded to Chaucer takes its cue from contemporary printed books. That readers often used printed exemplars as the basis for their manuscript corrections, glosses, and emendations conveys their belief in the narratives of print’s reliability promoted in those very books.Footnote 12

1.2 Against Chaucerisms

The case of jape would indicate that the archaism of Chaucer’s words caused them to be sometimes censured for their coarseness and indelicacy, but the prevailing evidence suggests that his words were more likely to be shunned for their sheer difficulty to early modern readers. These debates about the language’s incomprehensibility played out in contemporary commentaries and in the pages of Speght’s editions themselves – only to be swiftly despatched. A prefatory letter by the judge Francis Beaumont (d. 1598) which was included in the editions’ preliminaries acknowledges the duality of the charges against Chaucer’s language: ‘first that many of his wordes (as it were with ouerlong lying) are growne too hard and vnpleasant, and next that hee is somewhat too broad in some of his speeches’.Footnote 13 As with jape itself, a word with which early modern commentators explored the transgressive limits of Chaucer’s language and the deeds it describes, ‘broad’ here carries both a linguistic and moral charge, of which Chaucer must be cleared. Beaumont does so by asserting the poet’s commitment to the Horatian principle of decorum, exemplified in Chaucer’s aspiration to ‘touch all sortes of men, and to discouer all vices of the Age’ by reporting them truthfully.Footnote 14

The other common ‘reproofe’ against Chaucer concerns the difficulty of his words, deemed ‘hard and vnpleasant’ in the 1598 version of Beaumont’s letter, and ‘vinewed & hoarie’ in 1602.Footnote 15 At this time, the epithet ‘hard’ was itself a stock descriptor for difficult language of all sorts: the old, the specialised, and the foreign. Earlier in the century, someone involved in the printing of the 1553 edition of Pierce the ploughmans crede wrote a justification for the book’s appended glossary: ‘For to occupie this leaffe which els shuld have ben vacant, I have made an interpretation of certayne hard wordes vsed in this booke for the better vnderstandyng of it’. A list of forty-eight Middle English words with glosses follows, along with a concluding note: ‘The residue the diligent reader shall (I trust) well ynough perceive’.Footnote 16 As Beaumont’s comments on Chaucer’s language at the end of the century illustrate, however, the ‘hardness’ of these old words would only increase with time.

Having suffered from neglect through ‘ouerlong lying’, according to Beaumont, Chaucer’s words were out of use and seen by some as no longer suitable for readerly consumption. Yet this preoccupation with the fate of archaic English, which Lucy Munro terms an ‘anxiety of obsolescence’, also furnished the means for assuring its recuperation and continued veneration.Footnote 17 If Chaucer’s hard words could be singled out for their age, it was that same antiquity which enshrined them at the head of the emergent canon of literary English and whose rusticity, as E. K.’s preface to the Shepheardes Calender (1579) put it, could ‘bring great grace and, as one would say, auctoritie to the verse’.Footnote 18 In the same decade that Speght’s editions were published, Robert Greene’s Vision (1592), a penitential pamphlet concerned with literary merit and legacy, put these concerns into the mouths of Chaucer and his contemporary John Gower, whose ghosts appear as characters in the narrative. When the dialogue turns to Greene’s regrets about his juvenalia, this Chaucer-figure presents himself as an inspiring example: ‘whose Canterburie tales are broad enough before, and written homely and pleasantly: yet who hath bin more canonised for his workes than Sir Geffrey Chaucer?’ Gower counters that Chaucer’s case is not applicable to Greene: ‘No. it is not a promise to conclude vpon: for men honor his [work] more for the antiquity of the verse, the english & prose, than for any deepe love to the matter: for proofe marke how they weare out of use’.Footnote 19 For Greene’s ‘Chaucer’, his language could serve as both the basis for his literary canonisation and the incontrovertible ‘proofe’ that his work was out of fashion. In the right context, what seemed like the tell-tale mould of obsolescence could be polished into a dignified patina of antiquity.

In addition to facing accusations of broadness and difficulty, Chaucer’s language was subject to yet other forms of opprobrium. In 1553, Thomas Wilson’s The Arte of Rhetoric sneered that ‘The fine courtier will talk nothing but Chaucer’, a retort at fashionable men who imported affectations into their speech, and part of a wider indictment by Wilson of ‘ouersea language’ spoken pretentiously by gentlemen returning from abroad or using specialist language in their professions.Footnote 20 Partly for the obscure status of his own English by the late Elizabethan period, and partly for his reputation for absorbing into English ‘termes borowed of other tounges’,Footnote 21 Chaucer would posthumously become enmeshed in the inkhorn controversy, an impassioned debate which centred mostly (though not wholly) on the use in English of foreign words.Footnote 22

Chaucer was a visible and easy target in the fight against hard and specialist words, so it is little wonder that the period had, by the 1590s, developed a pejorative word for his language too. Chaucerism, a neologism probably coined by Thomas Nashe,Footnote 23 was synonymous with old-fashioned words which, according to Ben Jonson, ‘were better expung’d and banish’d’ in contemporary English writing.Footnote 24 The glossary at the end of Paul Greaves’s Grammatica Anglicana (1594) lists 121 items of ‘Vocabula Chauceriana’, but in fact contains many terms from outside the Chaucer canon.Footnote 25 The presence in the Workes of a wide range of apocryphal texts, some with distinctive styles and their own pseudoarchaisms, also contributed to an early modern impression of Chaucer’s hardness.Footnote 26 Suitable neither for poetic imitation nor easy comprehension, Chaucer became a byword for difficult, arcane, and obscure language, whose use in literary writing seemed inimical to the Jonsonian plain style.Footnote 27

It was against this background of Chaucer’s declining linguistic currency that Speght published his first edition of the poet’s Workes in 1598 and Beaumont prefaced it with an apologia countering the ‘obiections … commonly alledged against him’.Footnote 28 Beginning with Speght and Beaumont, Chaucer’s proponents issued new editions and adaptations of the poet’s writings for the early modern book trade. This was a bibliographic fix for a linguistic problem. Editions of Chaucer’s works had been a successful print commodity since Caxton, but numerous books of Chaucerian works published after 1598 shared the particular goal of recovering his language and rendering it accessible.

When it was published in 1598, Speght’s Chaucer edition contained the largest glossary of Middle English words available in print. Unlike the Life of Chaucer included in the editions, which relied heavily on materials collected by John Stow, the 1598 glossary seems to have been based on Speght’s own scholarship.Footnote 29 Both its scale and the importance it is accorded in the edition confirm the extent to which Chaucer’s Middle English had fallen into disuse. Speght’s glossary is advertised on the title page of the 1598 edition as a list of ‘Old and obscure words explaned’. It was first published with 2,034 entries, then augmented with 863 more in 1602, when it was corrected and expanded with the aid of Francis Thynne’s Animadversions.Footnote 30 Its inclusion on the title page suggests its novelty, for prior editions of Chaucer’s poetry had assumed and required a working knowledge of Middle English on the part of their readers. The commendatory poem by ‘H. B.’ that appears facing the engraving of Chaucer accordingly heralds the editor’s achievement to have ‘made old words, which were unknown of many, / So plaine, that now they may be known of any’.Footnote 31 The editing of Chaucer may have been an antiquarian project conducted by learned men, but the language of the prefatory material suggests that its intended readership extended beyond this group, to include ‘any’ one who might benefit from the glossary.Footnote 32

Beyond Speght, other efforts to update Chaucer for new readers and purposes were also underway. Amidst anxiety about the longevity of literary works ‘affecting the ancients’ – works exemplified by Spenser, whom Jonson derided as having ‘writ no language’ – early modern authors found that they need not imitate Chaucer’s archaic style to achieve literary credibility, but could instead draw upon him for new adaptations and translations.Footnote 33 Although no new editions of Chaucer were printed between 1602 and 1687, the poet and his works were everywhere present in the English book trade of the period: as the named inspiration for anonymous stories in The Cobler of Caunterburie (1590); as the pretext for Richard Braithwait’s anti-tobacco poem Chaucer’s Incensed Ghost (1617); as the subject of printed ballads; and in printed editions of plays such as Patient Grissil (1603) and Two Noble Kinsmen (1634), which reinvented his works for the stage. From the dozens of literary allusions, dramatizations, and adaptations for which records survive, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries emerge as a period of ‘cultural saturation’ with Chaucer.Footnote 34

Several of these books were innovative in their approach to Chaucer’s works, for they presented tools aimed at bringing him to new readers. For example, Richard Braithwait also wrote a posthumously published Comment upon the Two Tales of our Ancient, Renowned, and Ever Living Poet Sr. Ieffray Chaucer, Knight (1617), supplying a detailed scholarly commentary intended to accompany the texts of the Miller’s Tale and the Wife of Bath’s Tale.Footnote 35 Other reworkings of Chaucer were more thoroughgoing still. In 1635, Sir Francis Kynaston’s Latin translation of the first two books of Troilus and Criseyde was printed by Oxford’s university printer, John Lichfield.Footnote 36 The book was designed to be read alongside the Middle English, which Kynaston based on Speght’s edition and which he presented on facing-pages with the Latin. At the same time, Kynaston’s dedication and the book’s copious commendatory matter all underscore the necessity for this translation to safeguard the poet’s work from ‘ruin and oblivion’ (‘ab interitu & oblivione’).Footnote 37 Chaucer’s enduring presence in the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century book trade may seem at odds with the decline of his language which this chapter has been charting, but these books presented the poet in new garb, dressed up with aids for the promotion and understanding of his works. Some works of this nature circulated in manuscript, but never seem to have appeared in print. These include Jonathan Sidnam’s Paraphrase on the first three books of Troilus (c. 1630), whose subtitle describes it as written ‘For the satisfaction of those / Who either cannot, or will not, take the paines to vnderstand / The Excellent Authors / Farr more Exquisite, and significant Expressions / Though now growen obsolete, and out of vse’.Footnote 38 An adaptation and continuation (in couplets) by John Lane of the Squire’s Tale, although not published until 1888, was licensed for the press on 2 March 1614.Footnote 39 In the same period, an anonymous author composed Troelus a Chressyd, a dramatic work which adapts and translates Chaucer’s Troilus with Henryson’s Testament into a single Welsh text, now extant in one manuscript witness.Footnote 40 In these manuscript works, too, Chaucer’s Middle English works provided the source texts for this flurry of literary production, and his linguistic senescence offered a convenient pretext. The makers of these books ingeniously bridged a linguistic gap between Chaucer’s old books and a new readership. In doing so, they contributed to an English literary culture in which Chaucer’s works, in their new guise, remained alive and available to new readerships.

These ventures traded on Chaucer’s enduring cultural worth even as they sought to alter the forms in which readers encountered him. But new books of Chaucer which glossed and translated his hard words did not automatically replace their older counterparts. As this chapter argues, the interventions early modern readers made to medieval manuscripts constitute a rich and underexplored archive of print’s role in materially shaping the language in which Chaucer’s texts were conveyed. The rest of this chapter discusses the traces left by those who continued to read Chaucer in fifteenth-century manuscripts alongside print, and under this climate of linguistic change and textual anxiety. Their annotations, additions, and corrections witness them grappling with the poet’s old and error-prone language, and updating it using the versions of these texts they located in printed books. For these early modern readers, print served as a conduit to the better understanding and continued engagement with Chaucer’s works in older manuscript copies.

1.3 Glossing

CUL, MS Gg.4.27, a fifteenth-century Chaucerian anthology, preserves a record of one owner’s use of Chaucer’s printed books as an aid to reading older manuscripts. Copied about a century before Thynne published his 1532 edition, MS Gg.4.27 (hereafter Gg) represents the earliest surviving attempt to collect Chaucer’s works between two covers.Footnote 41 It had already been plundered, probably for its illustrations and borders, by the time Joseph Holland (d. 1605) acquired it around 1600.Footnote 42 With an imperfect manuscript in his possession, Holland – who was a lawyer, amateur herald, and member of the Elizabethan Society of Antiquaries – set about to furnish the resulting textual lacunae. Relying on Speght’s edition, his scribe also supplemented the manuscript with additional material, including a customised glossary of more than six hundred items.Footnote 43

Holland modelled the form and content of his Middle English glossary on the one printed in Speght (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2). Following the 1598 edition, Holland’s scribe ruled each of three parchment leaves into three columns, whose lines were embellished in red ink. Organised in alphabetical order, this new glossary took its title from Speght, ‘The old and obscure words of Chaucer explaned’ (fol. 30r). Like its printed exemplar, it was designed with care. Holland’s glossary allocated space for blue display capitals to be filled in as headings for each letter of the alphabet.Footnote 44 Where Speght’s edition supplies each Chaucerian lemma in black letter and its gloss in roman, the manuscript glossary presents headwords in a stylised italic hand and their corresponding glosses in secretary. The choice of title, mise-en-page, and hierarchy of scripts used in the making of a new glossary for Gg demonstrates the clear affinity between the printed model and its manuscript copy. Not only did Speght’s glossary transform the way Chaucer was read in print, but it also allowed readers like Holland to imagine new possibilities for approaching his works in older manuscript books.

Figure 1.1 Joseph Holland’s glossary adapted from Speght’s 1598 edition. CUL MS Gg.4.27(1), fol. 30r.

Figure 1.2 Speght’s 1598 glossary. Fondation Martin Bodmer [without shelfmark], sig. 4A1r.

Yet the glossary in Gg is a descendant of the printed version made by Speght, rather than its twin. Similar though they may be, the superficial resemblance between these two lists of Middle English words should not obscure their difference. Of 2,034 entries compiled by Speght in 1598, Holland’s contains only 661 – just under one-third. Sixteen of these, moreover, are additions not derived from Speght.Footnote 45 Elsewhere, Holland’s glossary significantly modifies the definitions provided in Speght. These alterations and additions vary in both degree and kind, and include changes such as Hine, ‘An hind’ to Hind, ‘servant’; Recreant, ‘out of hope’ to Recreant, ‘coward’; Slough, ‘dirty place’ to Slough, ‘ditch’; Cruke, ‘a pot, a stean’ to Cruke, ‘a post’; and apparent errors in transcription, such as Curreidew, ‘currie favour’ to Cureidew, ‘currifavour’. Conversely, the manuscript glossary sometimes rejects the printed definitions altogether, as for the words frouncen, hight, and misbode. These items are correctly glossed in Speght’s 1598 edition, but left blank in Gg. Two further features of the apparatus appended to the 1598 glossary – a list of Chaucer’s French words and a list of the proper names of authors cited by him – were also omitted in Holland’s updated manuscript.

It may initially seem that Holland, in imitating the glossary in Speght’s edition, intended to make Gg more closely resemble the recent printed book. Yet his glossary did not simply duplicate material from Speght in manuscript form, but shows sustained engagement, customisation, and interrogation of the printed exemplar, which were all part of a larger programme of perfecting planned for Gg. Although his glossary relied on the authority of the definitions provided by the printed book, it also constitutes a lexicographic study in its own right. As an antiquary who owned several manuscripts containing Middle English, Holland could certainly read Chaucer’s language and the scribe’s anglicana formata script, as is evident from his annotated passages in Gg.Footnote 46 He may have used Speght’s glossary as a reading aid, but did not require all 2,000 lemmatas furnished by the editor to read his own Chaucer manuscript. Reliant on his own knowledge and interests, his glossary represents a unique adaptation of Speght’s ‘hard words’ which occasionally demonstrates resistance to some of the glosses in the printed edition on which it was modelled.

Holland’s adaptations shed precious light on the pragmatic value of Speght’s glossaries in their own time. Pearsall has voiced his impression that Speght’s printed glosses are ‘mostly guesswork from context and common sense: most of the guesses are good, but some are completely off target’; some of these latter, despite having been mangled by the editor, enjoyed longevity as ‘ghost words in the dictionaries until the eighteenth century’.Footnote 47 While many of the glosses would have been essential for the less experienced readers anticipated in Speght’s front matter, most seem to have been of limited value to Holland. Nonetheless, it is worth emphasising that the print provided a basis for his own lexicographic investigations. This role of Speght’s printed glossaries in giving rise to new work is also apparent in a series of surviving notebooks and annotated copies of Chaucer’s Workes which once belonged to the distinguished Dutch philologist and scholar of Old English Franciscus Junius (1591–1677).Footnote 48 Bremmer has pointed to evidence for the circulation in the seventeenth century of an ‘enriched Index’ on Chaucer – presumably a fascicle of Speght’s 1598 glossary and end matter – detached from Junius’s surviving print copy and marked up with his annotations. Both the lost ‘enriched Index’ and Junius’s Chaucer glossary of nearly 4,000 words signal his use of Speght’s model as a starting point for his own meticulous study of Chaucer’s words. The surviving evidence of Junius’s and Holland’s reading at once suggests the innovation represented by Speght’s glossaries, their perhaps inevitable limitations compared to the work of the more learned readers, and consequently, their role in the incitement of more deliberate lexicographic scholarship.Footnote 49

Both his own experience and the ‘somewhat chaotic’ presentation of Speght’s word list may have played a role in Holland’s choice to study the meanings of several of Chaucer’s words independently.Footnote 50 The minutiae of Holland’s reading expose the limited utility of Speght’s glossaries to him, and complicate the prevailing picture that they were ‘found useful and considered authoritative’ by the makers of subsequent seventeenth-century lexicographies.Footnote 51 While the influence of Speght’s printed glossaries on later studies of old words is indisputable, the utility and authority that they embodied should also be recognised as a triumph of marketing and, more specifically, of typography. Speght’s printed word lists established a typographic distinction between Chaucer’s words (in black letter) and the editor’s modernised glosses (printed in roman), thereby tapping in to ‘the powerful combination of Englishness … and past-ness’ that the older typeface could represent.Footnote 52 That juxtaposition of an archaised typeface and a modern one on the printed page is an expressive visual sign of the editor’s willing role as the ‘interpretour’ (as Beaumont put it) of Chaucer’s words for certain early modern readers.Footnote 53 For all their lexicographic shortcomings, Speght’s glossaries succeed in ‘constructing the very sense of historical distance that they purport to resolve’.Footnote 54 The 1598 and 1602 glossaries might have been an effective piece of visual rhetoric, but their partial use by Holland indicates that learned readers did not take their authority for granted.

Holland’s glossary amounts to much more than a copy of Speght’s, and it remains an exceptional record of how an early modern reader might use the printed Workes as a model for approaching and updating the language of older manuscript books. But the conditions and challenges of reading that it reveals were familiar to many early modern enthusiasts of Middle English. Reading Chaucer in manuscript, and lacking the option or desire to commission a new glossary, some readers improvised other ways of using print to make old books more readable: by adding marginal glosses or interlinear corrections, reversing archaic word order, and replacing old words with more familiar ones. Like Holland’s list of 661 glosses, the corrections of these readers betray a worry about the age of Chaucer’s words and a concomitant anxiety about the material books which conveyed them. For some readers, printed editions of Chaucer, with their modernised or glossed language and a stance of textual authority, offered a conveniently packaged solution to such problems.

The linguistic utility of newer printed books to readers of old manuscripts is amply demonstrated by another book, St. John’s College, Cambridge, MS L.1 (hereafter L1).Footnote 55 Acquired by the college in 1683, L1 is a manuscript copied as a stand-alone codex of a single work, Troilus and Criseyde, in roughly the third quarter of the 1400s.Footnote 56 Sometime in the course of the seventeenth century, two readers of the fifteenth-century book undertook to improve its text. They did so by supplying marginal glosses to Chaucer’s hard words, and by emending the text where they deemed it faulty or lacking. Where Holland’s glossary was a pre-planned and professionally executed tool for countering Chaucer’s archaism, the marginal annotations in L1 share an ad hoc quality which preserves readerly responses to the Middle English text, localised on the page. The improvised and reactive nature of such marginalia, written alongside the scribally copied text, allows us to shadow the thought-processes of these historical readers as they read and updated their Chaucer. For example, in the very first correction, on fol. 1v (see Figure 1.3), one of the annotators (who Beadle and Griffiths call Scribe 7) underlined and modified L1’s original reading, involving the narrator’s opening plea on behalf of lovers, to ‘sende hem myght hir ladys so to plese’ (1.45). Instead, this annotator favoured another reading, ‘And sende hem Grace her loves for to plese’. Our annotator also took the opportunity to record the source, for a handwritten note in the margin indicates that the newly supplied reading appears ‘in printed books’. In the pages of Chaucer’s poem that follow, the two annotators scrupulously noted and corrected points of difficulty and disjuncture between the manuscript and the printed version they used as exemplar, Speght’s 1602 edition.Footnote 57 The result was a more legible, accurate, and complete version of Troilus as they determined it.Footnote 58

Most of the early modern glosses in L1 supply modernised words in place of their archaic equivalents. For instance, peacock was substituted for pocok (fol. 3v); royal for real (fols. 7r, 63v); man for wight (fol. 16v); dignity for deyte (fol. 56r); knees for knowes (fol. 64r); and supper for soper (fol. 100r). A second, less common category of gloss aimed at improving the text’s legibility rather than providing new readings. These sometimes took the form of expansions to the scribe’s contraction of the letters in some Middle English words, as in ‘Perauntur’ (fols. 9v, 10v); ‘prouerbes’ (fol. 11v); ‘seruen’ (fol. 20r); ‘vertules’ (fol. 21v); ‘comparisoun’ (fol. 74v); and ‘sermon’ (fol. 87r). Equally, for these annotators glossing entailed the re-transcribing in the margins of words which had proven difficult to read in the text’s anglicana script. This was the case for soule (fol. 1v); stil (fol. 3v); harme (fol. 5v); beareth (22r); cheare (23r); and espie (fol. 27v). Although glosses which improve the legibility of the written text are comparatively few in number, they offer a direct insight into the practical challenges faced by early modern readers of medieval manuscripts. Antiquary Peter Manwood’s complaint about his difficulties in reading an ‘ould hande out of use with us’ is emblematic of the obstacles that archaic scripts might raise even for experienced readers of old manuscripts.Footnote 59 Modern palaeographers have taken care to emphasise the great variety of scripts to which premodern readers might be exposed, and the differing degrees of legibility that each might present.Footnote 60 Secretary, chancery, mixed, or round hands were in regular use in England over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but their legibility to different sorts of readers should not be taken for granted.Footnote 61 By the same token, we should not assume that more archaic hands – the predominantly anglicana hands of Gg or L1, for example – were easily or immediately decipherable. In L1, the problem of legibility was compounded by the ‘free use of abbreviation’ in the scribe’s Middle English text, reflecting perhaps the work of someone with ‘a professional expertise probably cultivated in the writing of Latin’.Footnote 62 As the glosses of these Troilus annotators attest, an outmoded or idiosyncratic hand might pose challenges even to experienced antiquarian readers. The presence of archaic scripts made the later reading of medieval manuscripts a distinctive experience, marking them visually and perhaps affording their readers some pride in their palaeographical accomplishments.

In all the examples listed here, and in virtually every instance of glossing in L1, the glosses to these old or illegible words were copied from Speght. For this pair of annotators, the printed edition was an authoritative witness to Chaucer’s text. Yet the textual interventions in L1 did not follow the glossary of hard words provided by the editor, nor did they update all points of textual divergence between the manuscript and Speght. Like Holland’s glossary in Gg, the choice of which words to gloss and which lines to correct was dictated by the annotators’ knowledge and readerly needs. The historical circumstances behind these decisions – such as whether readers glossed books for their own convenience or for future readers with less competence in Middle English – cannot be recovered. What remain, though, are copious traces of reading which illuminate some aspects of the encounter between readers and old books.

Here, the annotations show these readers consulting old and new volumes in parallel, and using a variety of techniques for updating Chaucer’s language. The glosses in L1 serve to modify hard words, expand unfamiliar abbreviations, and transcribe illegible marks. Chaucer’s language may have been the biggest barrier that his early modern readers faced, but it was not monolithic in nature. The problem of archaism included the challenge of reading these words in books that were themselves old; readers could struggle to make out the words written on the manuscript page, as well as to understand their meaning. Like those who annotated L1, they might grapple with outmoded scribal hands, or strain to make sense of the orthographic and palaeographical tics transmitted by individual copyists, manuscripts, and textual traditions. Such readers looked to newly printed books to aid their comprehension of these and other features of the Chaucerian manuscript text.

1.4 Collating and Correcting

The annotations of early modern readers show that archaism of language and script were not the only obstacles to the early modern reading of Chaucer in medieval manuscripts. The annotators of L1 also moved beyond glossing hard or hard-to-read Middle English words, and used printed books to supplant readings found in the manuscript with new ones. Indeed, the dominant mode of readerly intervention in MS L1 is not the lexical gloss, but the textual emendation. On the whole, the L1 annotators appear less interested in modernising words or syntax than in selectively supplying missing words and reconciling discrepancies between the manuscript and printed book. They paid especial attention to correcting the text at certain key points in the narrative – for example, on fol. 2r (1.92 ff), when Criseyde is introduced, or in the Latin argument to the Thebaid on fol. 114r (V.1498a ff).

For early modern readers, this concern with textual exactness is rooted in Chaucer’s primacy within the vernacular literary canon; his words mattered in a way that those of no other English author did. Consequently, that cultural import gave the philological efforts of his early editors particular urgency. The printed books they produced aimed to embody a model of reassuring textual constancy. In 1532, William Thynne described his attempt to establish a copytext from ‘bokes of dyuers imprintes’. In this process, he identified ‘many errours, falsyties, and deprauacions, which euydently appered by the contraritees and alteracions founde by collacion of the one with the other’.Footnote 63 Thynne’s professed ‘collacion’ did not involve the study of the codex’s constituent parts; that would come much later, with the work of another Chaucerian, the nineteenth-century Cambridge librarian Henry Bradshaw (1831–86).Footnote 64 Rather, Thynne’s collation refers to a more fundamental bringing together of different texts for the sake of comparison, and gives the OED its first usage of the word in this particular sense of establishing textual likeness and difference.Footnote 65 Displeased by the printed ‘contraritees’ revealed by his collations, he resorted to a search for ‘very trewe copies or exemplaries of the sayd bookes’, and was successful. ‘Nat without coste and payne’, he stresses, ‘I attayned, and nat onely vnto such as seme to be very trewe copies of those workes of Geffrey Chaucer, whiche before had ben put in printe, but also to dyuers other neuer tyll nowe imprinted, but remaynyng almost vnknowen and in oblyuion’. Thynne’s concept of collation, with its distinction between ‘falsyties’ and the ‘very trewe’, gives error a moral tinge. For Thynne, faulty words had no place in Chaucer’s collected works, and it became his job to banish them. ‘I thought it in maner appertenant unto my dewtye’, he wrote, ‘and that of the very honesty and loue to my country I ought no lesse to do, then to put my helpyng hande to the restauracyon and bryngynge agayne to lyghte of the sayd workes, after the trewe copies and exemplaries aforesaid’.Footnote 66 Like the humanist editors who prepared books for the early European presses – and who called themselves correctors and castigators – Thynne’s rhetoric frames his work in terms of virtuous rigour.Footnote 67 By his own measure, his edition represents the culmination of that dutiful effort: a bringing together of different texts, and a bringing to light of the best version of Chaucer’s works.

For the humanists in whose tradition Thynne was working, collation was a means of ensuring a text’s accuracy, a method that gave rise to ‘a culture that staked reputation on practices of emendation and castigatio’ and in which readers ‘corrected errors out of habit and out of self-respect (lest others think that they had not noticed the error)’.Footnote 68 During the Reformation and its aftermath, annotation and collation would become scholarly weapons in the bitter fight over doctrinal orthodoxy. The bibliographical spoils of the religious houses were thoroughly combed by the scholars of post-Reformation England in their quest to write a new national history.Footnote 69 The practice is exemplified in the figure of Thomas James (1572/3–1629), Bodley’s first librarian, and a diligent searcher of manuscripts. During the course of his life, James devoted significant energies to correcting manuscript and printed texts containing writings of the Church Fathers, which he feared had been corrupted by their former Catholic custodians.Footnote 70 In 1625, near the end of his life and after his retirement from Bodley’s library, he wrote about his plans for correcting faulty ecclesiastical documents through the hiring of twelve scholars for a lengthy project of collation. ‘[B]ut if I may haue my will’, he vowed in a detailed description of the scheme, ‘no booke of note or worth shall goe vncompared’.Footnote 71 James’s practice of collation centred on several precepts, including the authority of old manuscript copies, the comparison with early printed witnesses, and the subordination of individual judgements to the readings found in the oldest or most numerous manuscripts. His vision of textual recovery was lofty, but it was grounded in the minute and fuelled by a worry about the insidiousness of error:

There is no fault so small, but must be mended, if it may, but noted it must be howsoeuer: these are but seeming trifles I must confesse, yet such as with draw men from the true reading, and draw great consequences with them.Footnote 72

In their meticulous editorial principles, James’s dicta model a form of textual criticism which pursues the ideal of an unblemished text. His 1625 tract also includes a list of ‘seuerall bookes … rescued out of the Papists hands, and restored by me’.Footnote 73 In late sixteenth-century England, this worry about the reliability and completeness of old books was the inevitable response to the destruction, loss, and suspicion that coloured the relationship to the past.Footnote 74 While the religious impetus behind James’s project was particular to his own beliefs and historical moment, in his attention to ‘seeming trifles’ – to correction on the level of the individual word – his careful comparison of historical texts resembles the work of philological recovery undertaken by editors like Thynne and readers like those of L1.

The early modern annotators of L1 similarly show themselves as keenly alert to the manuscript’s possible shortcomings. Throughout the text of Troilus in that book, words and phrases deemed incorrect were underlined, and the annotators supplied Speght’s 1602 readings in the left and right margins of many pages. Speght’s readings were not always correct, however, and the annotators’ fidelity to the editions occasionally reveals the impenetrability of Chaucer’s language even to experienced readers of medieval manuscripts. For example, there is a moment where the poem’s narrator describes Criseyde’s loving of Troilus despite his shortcomings, ‘Al nere he malapert, or made it togh’ (111.87). The second later annotator (Beadle and Griffiths’s Scribe 6), who wrote a more cursive secretary with distinctive ticks over the letter c, intervened to underline the unfamiliar word and correct the thorny line. Following Speght, the handwritten marginal note suggests that ‘malapert’ – meaning presumptuous or overly self-assured – be replaced with ‘in all apert’, in a misreading of the initial three minims which had bedevilled the scribes of other Troilus manuscripts, too.Footnote 75 In an attempt to emend this line in L1, the annotator inadvertently corrupted the correct text in favour of a faulty reading reproduced in the printed book. Such moments – where corrections made according to the printed text introduce rather than banish error – serve as telling reminders of the chasm between the avowal of accuracy and its more elusive attainment.

Elsewhere in the manuscript, the corrections from Speght appear not in the margins but as annotations inserted between words using carets, which visually disrupt the original scribe’s neat anglicana script. In some cases, where whole stanzas in the original manuscript are out of order (fol. 61v) or altogether missing (fol. 13v), the new annotators corrected the errors by cancelling the original text and recopying the text from Speght in what seemed to be its rightful place. On fol. 61v, for example, appear two stanzas in which the narrator interrupts a description of the lovers’ meeting to address his audience. His interjection is a typically tentative statement about his lack of experience in love, which he claims affects his ability to render the scene: ‘For myne wordes, heere and every part, / I speke hem alle under correccioun / Of yow that felyng han in loves art’. Neatly, it is this stanza and the one preceding it (111.1324–7) that the annotator undertook to correct and move to the previous leaf following Speght, as though he took seriously the narrator’s injunction to ‘encresse or maken dymynucioun / Of my langage’ according to his ‘discrecioun’ (111.1335–6). As Windeatt has observed, surviving manuscripts of Troilus collectively register doubt about the placement of these stanzas, which appear at different positions in other copies.Footnote 76 Confronted with one fifteenth-century text and a different editorial choice in Speght, the early modern annotator chose the authority of the printed book, and left carefully cross-referenced notes in Latin to signal the correct order. On fol. 61v, the originally copied pair of stanzas has been cancelled by a large bracket and the note ‘vide folium praecedens’ added, while the stanzas have been recopied onto fol. 60v, together with construe-marks and signes de renvoie indicating where the newly transposed text should be placed.Footnote 77

The energetic correcting in L1 demonstrates resistance to the seemingly flawed readings transmitted in the manuscript. And in correcting the Middle English written by the original scribe – not always for the better – the later annotators express their preference for the updated language and textual variants transmitted in Speght. Why did they trust the reliability of Speght’s edition over the medieval manuscript? Or, to put it differently, why did they correct the manuscript using the printed book rather than vice versa? The annotators’ approach to the pair of books reveals a set of assumptions about the textual value of L1 relative to the printed volume and encapsulated in the first marginal note which cites a new reading as it appears ‘in printed books’. To privilege the readings of Chaucer in print suggests their belief in the reliability and authority of the printed text, error-prone though Speght’s edition has since proven to be.Footnote 78 L1 contains few traces of readerly engagement in the conventional sense (for instance, subjective reader responses to Chaucer’s characters or narrative), yet the marginal notes of the L1 readers preserve their studious and sustained attention to Chaucer’s language and texts as they navigated between the manuscript book and its printed counterpart in pursuit of comprehensibility and correctness. The glosses and corrections copied from Speght into L1 document the annotators’ concern with the clarity and accuracy of the Chaucerian text, a twofold problem which some readers attempted to solve by copying readings from printed books into older manuscripts. For such readers, their updating of hard words was not confined to anxiety about Chaucer’s linguistic archaism, but part of a broader sense that the language and texts contained in his antiquated manuscripts could be renewed and perfected using printed books. At the basis of this belief in the authority of print is the desire for an error-free text, an imaginary ideal to which printed editions aspired and which readers’ corrections imitated.

The degree to which concerns about the hardness of Chaucer’s language were paired with – and sometimes, superseded by – doubts about the text’s accuracy is borne out by another manuscript, Bodl. MS Laud Misc. 739 (hereafter Ld2). In this book, a late fifteenth-century manuscript of the Canterbury Tales, the Middle English of the original scribe has been glossed and emended by a sixteenth-century reader, again using a printed edition of Chaucer, possibly a Caxton, for comparison.Footnote 79 And so this manuscript, which Manly and Rickert condemned as ‘very late, corrupt, and of no authority’, had a new authority vested in it through corrections from a print.Footnote 80 Here, as in L1, textual emendations significantly outnumber glosses. By my count, there are no fewer than 451 later corrections in Ld2, written in at least two early modern hands. Glosses or identifications of obscure words account for 48, or roughly 11 per cent, of these. The glossing was mostly done in a secretary hand, perhaps of the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. For example, hard words such as gryse (fol. 3v), lyte (fol. 23v), and athamaunt (fol. 30v) were glossed respectively as ‘grey fur’, ‘littl’, and ‘everlasting diamand’. Proper nouns were also singled out for glossing, such as Phebus as ‘the Sun’ (fol. 23r), or Cythera, which received a fuller treatment: ‘so called after the name of an Ilond in the gulf of Laconia on the sowth part of Greece Seruius’ (fol. 34r). Some words, on the other hand, were marked for glossing but never filled in. Of the forty-eight hard words identified in the manuscript, nineteen are unglossed. But the intention to eventually gloss them is indicated by tell-tale asterisks inserted in the text and sometimes duplicated in the margins, where the notes would have been written. The unglossed words marked out for later explanation include cheuyshaunce (fol. 4r), clarre (fol. 18r), shode (fol. 31r), and bone (fol. 34r). It does not seem that the copyist responsible for this work had access to Speght’s glossary, which defines several words which were marked as troublesome in Ld2 but were ultimately left unglossed.

By far, the largest category of correction in Ld2 is the addition of new words (45 per cent), as in one of the first lines of the Canterbury Tales, which in this manuscript reads: ‘Whan Zepherus wyth hys soote breth’ (fol. 1r).Footnote 81 In the hands of the later annotator, this becomes, ‘Whan Zepherus eke wyth hys soote breth’. After the addition of new words, the second most frequent type of correction is the replacement of existing words with some similar variant (35 per cent). This may have been done for orthographic or metrical reasons, or to excise corrupt readings. For instance, on fol. 19r, the medieval scribe has copied a line in the Knight’s Tale which describes Arcite’s wish to remain a captive of Theseus (so that he may still catch glimpses of his beloved Emily from the window of his cell).Footnote 82 Probably following Caxton, the later annotator altered the line by adding a possessive pronoun to refer to Theseus and emending moore to moo:

Yfetrede in ^hys prison for euer moore

These examples of adding words and emending their spelling are particularly noteworthy because they also introduce archaisms transmitted in print into the older manuscript. Both eke and evermoe were obscure words by the sixteenth century. Spenser liberally sprinkled eke throughout his archaic English, and the orthography of euer moo and its variants was by this time distinctively outdated compared to evermore.Footnote 83 Introducing eke as the annotator did corrects the line’s metre, but the emendation from euer moore to euer moo is not so easily explained. Rather, this latter correction records the annotator’s pursuit of textual authenticity, even perhaps at the expense of clarity. In at least one case, the same hand emended the original scribe’s lyke to ylyke (1.1374, fol. 21v). The corrections, then, do not only facilitate the understanding of Chaucer’s language, but occasionally do the opposite: they introduce hard words and spellings which lend a seeming authenticity to the text and perhaps an ‘auctoritie to the verse’, as E. K. would have it.Footnote 84

After glosses, new words, and new variants, the other categories of correction in Ld2 – writing over erasure, supplying missing lines, changes to word order, and cancellations – supply the remaining 10 per cent.Footnote 85 The range of textual alterations made in a book like Ld2, glossed and corrected against a printed copy, shows that there was more at stake in this work of annotation than just cracking the text’s impenetrable language. Although this reader sometimes glossed the text’s hard words, the corrections as a whole are less concerned with comprehensibility – achieved by updating Chaucer’s Middle English – than with the accuracy of the book’s Middle English.

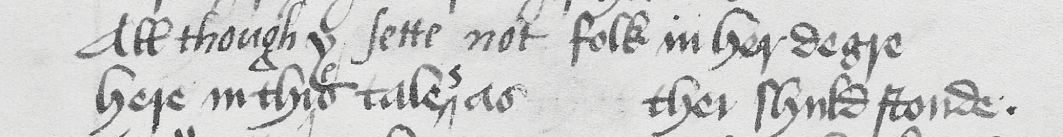

For that reader, a better version of Chaucer’s text was to be located in a printed copy. The annotator’s reliance on the printed edition is most striking at points where perceived or actual errors left by the original scribe were found and corrected. This is the case on fol. 12r, where the words have been rearranged in a pair of lines as follows: ‘All <though> y <sette not> folk in her degre / Here in thi^es tale^s as thei shuld stonde’ (see Figure 1.4).Footnote 86

In these two lines, at least four erasures have been made: three at the points where though and sette not are now written over the erasures, and one between as and thei, where the trace of a word by the original scribe is just visible, and the space created by erasure has been left blank. The effaced words suggest that someone was bothered by the unusual grammar and syntax of the original line (‘All haue y’).Footnote 87 It is difficult to say who, whether original scribe or later annotator, is responsible for these erasures. But the ink corrections, written in by the later annotator, record a clear attempt to fill these gaps, and to set Chaucer’s words in order. This form of correction, in which the annotator has written over erasures in the main text block, occurs twenty-five times in Ld2. Our annotator had no qualms about other invasive modes of correcting, such as striking through the original text, or squeezing new words into existing lines using carets, and may have even been responsible for the rubbed-out words and phrases.Footnote 88 At the very least, these annotations written into gaps created by erasure demonstrate an opportunistic use of blank space to put the text right.Footnote 89 The new readings supplied in these empty spaces follow Caxton in nearly all cases.Footnote 90

The annotations in these manuscripts of Troilus and the Canterbury Tales show readers wresting Chaucer’s language and text into a form they believed to be more comprehensible, more accurate, or more authentic. All of the medieval books discussed in this chapter passed through the transforming hands of such readers, who modified them based on texts they read in parallel, and typically in print. At the same time, the form of this imitation is always varied, and reveals a rich archive of corrective reading habits which diverge in each reader’s preferences and particularities. In Ld2, for example, the annotator responsible for the emendations was extremely attentive to the text, but only at certain points in the manuscript, principally the General Prologue, Knight’s Tale, and Man of Law’s Prologue and Tale (fols. 1–46 and 81–98). By contrast, the annotator skipped over the roguish tales of the Miller, Reeve, and Cook, which are scarcely touched. But the annotator was paying attention even at those moments where they appeared to lose interest, or at least interest in correcting. This is clear at one point in the manuscript’s twelfth quire, which should have contained the end of the Wife of Bath’s Prologue. The annotator’s collation revealed that a section of text was wanting, so they tipped in a new leaf supplying the missing twenty-eight lines at this point (fol. 140ar); the Prologue and its Tale are otherwise virtually uncorrected.Footnote 91 The glosses and corrections in Ld2, which number in the hundreds, showcase the array of reading habits that early modern readers might bring to an old manuscript book. In doing so, they reveal aspects of the medieval text – its orthography, syntax, and perceived errors or incompleteness – which later readers strove to update and improve.

The preference for selective correcting present in Ld2 is also evident in BL, MS Royal 18 C.11 (Ry2), a parchment manuscript of the Canterbury Tales copied around the second quarter of the fifteenth century. In this book, the Parson’s Tale has been annotated by at least two early modern readers. The first added finding notes in dark ink (e.g. on fols. 238r–247r, 267v–270v), leaving marginal comments to mark ‘actions of penitence’ (fol. 238v), ‘iiii thinges to be considered in penitence’ (fol. 239r), and ‘the spices of penance’ (fol. 238v). While this mapping out of the text with finding notes served an immediate practical purpose, it might also reflect the reader’s familiarity with the ordinatio of devotional prose texts found in Middle English manuscripts, in which marginal notes by scribe or author were often embedded as a navigational aid.Footnote 92 The second annotator would eventually correct one of those marginal notes, changing it to ‘the speces <or kinde> of penance’. This reader, who wrote in a lighter, now brownish ink, and worked on the book at a later point, supplied corrections from a printed edition at moments where the original text seemed incomplete or faulty.Footnote 93 These corrections ranged from small to substantial, from adding an a to ‘pyne’ to describe the ‘p^ayne of helle’ (fol. 240v), to marginal insertions of whole clauses more than twenty words long which were wanting in the manuscript.Footnote 94 As in the case of the corrected parts of Ld2, this reader’s collation of the Parson’s Tale provides additional insight into the early modern reception of the Canterbury Tales. The choice to correct only the Parson’s Tale would appear to confirm that tale’s popularity with later readers who mined it for sententious matter.Footnote 95 But the annotations, while densely concentrated in this single tale, do not mark out quotations for commonplacing. Instead, the second annotator aimed to fix obvious errors where they appeared in the manuscript, to furnish omitted words and phrases, and to reconcile inconsistencies in favour of the printed edition. Textual correctness is, after all, an indispensable quality for the Parson’s contribution to the storytelling game, a work modelled on the penitential manual and celebrated as ‘the tale to end all tales’.Footnote 96 These corrections might reflect their especial awareness of the tale’s religious and moral authority and its dependence, in turn, on textual authority.Footnote 97 Alternatively, the Parson’s Tale might be the only annotated tale in Ry2 because it was the only one these particular annotators read, and they might have chosen it for its edifying matter.

Although Chaucer’s reputation as a vernacular classic was founded on his ‘reverent antiquity’, this venerability, as Sir Philip Sidney knew, was not without its ‘wants’.Footnote 98 Older, then, was not necessarily better. It was this possibility of historical deficiency which made medieval manuscripts containing Chaucer’s works particularly susceptible to correction by his early modern readers. The linguistic and textual corrections by later readers register, in parvo, their doubt about the accuracy of his works as transmitted in manuscript. Chaucer’s words were obscure as well as old and, for some readers, this prompted concern about the other ways in which old words written in manuscripts might be unreliable. Reading Chaucer in scribally copied books forced readers to confront the poet’s text in all its unfamiliarity, which extended beyond the hardness of certain words to include challenges which have long been familiar to scholars of medieval manuscripts – scribal error, idiosyncratic spelling, variance, and exemplar poverty amongst them.Footnote 99

Readers nevertheless coveted, sought out, bought, and borrowed these old books, for they were objects of antiquarian desire. Chaucer’s manuscripts might be laden with obscure and unreliable words, but they were still valuable, intriguing, and worth collecting. The perfecting of manuscripts according to seemingly superior printed texts offered readers a means of marrying the desirable qualities of the old books with authoritative readings. One such collector, who typifies the twinned impulses to preserve and perfect medieval manuscripts, was William Browne of Tavistock (1590/91–1645?). Browne’s life and work were dedicated to antiquarian and literary pursuits. He is today classed amongst a circle of Jacobean Spenserians including George Wither and Christopher Brooke, and his major work, Britannia’s Pastorals (1613), is an ambitious pastoral epic indebted to Drayton’s national poem Poly-Olbion (1612). As a collector of medieval manuscripts, Browne’s focus was Middle English, with a particular emphasis on Hoccleve.Footnote 100 He owned at least one medieval manuscript of Chaucer, a fifteenth-century copy of Troilus and Criseyde which also contains, amongst other items, Hoccleve’s Letter of Cupid.

In this book, now Durham University Library, Cosin MS V.11.13, Browne’s signature appears on fol. 4r, at the beginning of Chaucer’s Troilus. He singled out certain lines with his characteristic annotation mark (a pair of short, vertical parallel lines slightly slanted to the right), identified similes, and added finding notes. He also corrected the Middle English text by filling in faded letters, supplying missing lines, and emending individual words and letters, perhaps according to Stow’s printed edition.Footnote 101 The copying error ‘To Simphone’, for example, is marked with an asterisk and is substituted in the margin with the Fury’s name, ‘Thesiphone’ (fol. 4r). In certain places, Browne cancelled words written in the set secretary hand of the scribe to emend ‘youre’ to ‘my’, ‘mars’ to ‘March’, and ‘spite’ to ‘space’ (fol. 25r). Elsewhere, he filled in faded letters in the words ‘Route’, ‘Ride’, and ‘be’ in imitation of the scribe’s secretary script (fol. 23r). Browne’s corrections, which number about thirty, seem to have been part of a broader programme of perfecting medieval manuscripts.

His intention to put faulty books right is best attested in another book, Bodl. MS Ashmole 40, a copy of Hoccleve’s Regement of Princes. Here, Browne’s close reading of the text is evident in dozens of finding notes and commonplace markers discreetly written into the manuscript’s margins. His textual emendations are fewer than in his Troilus manuscript, but he corrected the text in other ways: by filling in blanks left by the scribe (for example, on fols. 7r, 10v, and 43v), transcribing missing stanzas (fols. 40v and fol. 80r), and by copying and inserting three leaves which were missing in the manuscript (fols. 65, 70, and 74). In the first Eclogue of The Shepheards Pipe (1614), published early in his period of manuscript acquisition, Browne had included a modernisation of Hoccleve’s Gesta story of Fortunatus, based on another of his manuscripts.Footnote 102 His printed edition included a postscript about the text and its author: ‘THOMAS OCCLEEVE, one of the priuy Seale, composed first this tale, and was neuer till now imprinted. As this shall please, I may be drawne to publish the rest of his workes, being all perfect in my hands. Hee wrote in CHAUCERS time’.Footnote 103

Browne’s comment that Hoccleve’s ‘workes’ were ‘all perfect in [his] hands’ offers some insight into his bookish habit and its status as a source of the collector’s pride. Well connected within London antiquarian circles due to his association with the Inns of Court, Browne owned several manuscripts that had formerly belonged to Stow, and it is possible that he consulted John Selden’s library, too.Footnote 104 His love for collecting old manuscripts, however, did not preclude his altering and transforming them. For Browne, this textual transmission could flow in both directions. As we have seen, during the period that he was using alternative copies of Hoccleve and Chaucer to supply gaps and correct errors in his own Middle English manuscripts, he was also preparing part of another Hoccleve manuscript for the press. Browne’s collation and close comparison of old books with their newly printed counterparts is also evident elsewhere. In BL, Additional MS 34360, an anthology of mostly Lydgatean works, he noted beside Chaucer’s Complaint to his Purse that ‘Thus farr is printed in Chaucer fol. 320 vnder ye name of Tho: Occleeue’, referring to Speght’s 1602 edition, where the poem is misattributed.Footnote 105 His use of a range of authorities – new and old, manuscript and print – in his efforts to make them ‘all perfect’ exemplifies the fruitful reciprocity that could exist between print and manuscript books in Browne’s day.

In his manuscript of Troilus, he was principally concerned with making the book easier to navigate through marginal glosses and with removing errors which marred its text. His study of that book was meticulous and displays, in the words of A. S. G. Edwards, an ‘attention to textual detail [that] is striking in itself’, as at one point on fol. 58v where he corrected the rhyme scheme.Footnote 106 These efforts to collect medieval manuscripts and perfect their texts thus resolve into a portrait of another aspect of Browne’s literary life. In one respect, his reading of Middle English manuscripts and his tendency to collate them with printed editions reflect his editorial aspirations and a scholarly attention that would come to inform the later field of textual criticism. That the collations undertaken by Thynne and other editors in order to produce a copytext are now well known means that the practice of textual comparison has become yoked to editorial work intended for publication, but the cases this chapter has been documenting fall largely outside this purview.Footnote 107 It has recently been suggested by Jean-Christophe Mayer, in relation to Shakespeare’s early modern readers, that ‘The extent to which the owners of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century editions of Shakespeare engaged with these books by collating, modernising or even reinventing them is greatly underestimated’.Footnote 108 Despite their seeming removal from networks of print publication, these readers were, for Mayer, ‘directly involved in the process of editing’ and did so ‘[o]ften simply for pleasure’. The evidence left by early modern annotators of Chaucer’s medieval manuscripts reveals that they, too, comprise a category of collating readers whose interest in perfecting the poet’s text has previously been overlooked. Amongst the early modern readers who collated Middle English manuscripts with print, Browne, with his editorial eye, was not exceptional. Rather, his textual interventions reflect the spirit of renovation that readers like Holland and the annotators of Ry2, Ld2, and L1 also brought to the words contained in their old manuscript books.

1.5 New Books with ‘termes olde’

Collectively, the marks left by these later readers corroborate glossing, correcting, collating, and emending as significant aspects of reading Chaucer’s manuscripts in early modern England. This practice, by which readers took to old books with the intent to improve their texts, is perhaps to be expected of an intellectual and bibliographical culture that was acutely alert to the possibility of error. For books printed during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, errata leaves and pasted-in correction slips were part of the furniture.Footnote 109 Self-consciously directed at fastidious readers, printed lists of faults escaped made a scholarly spectacle of error and its removal.Footnote 110 The glossary in Speght’s 1598 edition itself conjures the spectre of error by way of a Latin tag from Horace printed at the end of the list of hard words: ‘Si quid novisti rectius istis Candidus imperti’ [if you can improve these principles, tell me].Footnote 111

Yet within this well-documented culture of correcting, surprisingly few printed books appear to have had their texts corrected by readers. H. S. Bennett estimated that 75 per cent of the ‘some thousands’ of printed books examined in his survey contained no manuscript corrections and that errata were ‘for the most part ignored by readers’.Footnote 112 How to account for this conspicuous absence? It is possible that readers only silently emended the text as they read, and it is certain that some readers of such books had not mastered the more advanced skill of writing.Footnote 113 Alternatively, such corrections may have been part of those copies read to pieces, or of those copies cleaned by later owners in their zeal for pristine margins.Footnote 114 It is equally possible, as Adam Smyth suggests, that the errata list had less of a prescriptive function than a ludic, even literary role in the early modern printed book, where it could serve as a ‘rhetorical set piece’ to signal the book’s status as book.Footnote 115 Whatever the interpretative possibilities of the errata list, that ubiquitous reminder of print’s imperfection, the reticence of their readers to correct and emend throws the early modern corrections to Chaucer manuscripts into fine relief.

This silence in the margins of printed books is relevant to my discussion for two reasons. First, it is a reminder that early modern correcting by readers, like the medieval scribal correcting studied by Daniel Wakelin, was ‘not an automatic or unreflective thing to do’ but which, in its pursuit of accuracy, ‘witnesses processes of thinking consciously about language and texts’.Footnote 116 The resultant texts, while not verbatim transcripts of their printed relatives, preserve the worries about correctness and comprehensibility that readers brought to their manuscripts, and their scholarly attempts to improve them through collation with other books, especially printed ones. This attention to language, evident in the impulse to gloss hard words and fix errors, might be an entirely typical response to a faulty and difficult text. At the same time, the work of glossing and correcting laid out in this chapter is only possible when readers are paying close attention. The readers studied here did not merely register and mark out hard or incorrect words. They also went to the trouble of finding comparison volumes and performing the tedious and technical work of collation to produce what they deemed to be a better text.

Second, the relative absence of readers’ corrections surviving in printed copies spurs further questions about the presence of correction in manuscripts more generally. In the case of books containing Chaucer’s works, printed volumes seem less liable than manuscripts to be corrected by early modern readers, a trend that may be attributed both to the stance of authority assumed by print and to the desire for accuracy on the part of those readers who sought out manuscripts.Footnote 117 In a similar vein, we might ask whether certain media, genres, or authors inspired more frequent and energetic emendation by their readers. While the majority of research on early modern correcting has focussed on their appearance in printed books, isolating particular media like manuscripts or genres such as historical texts might better allow such trends to emerge.Footnote 118

To further contextualise the early modern annotations studied in this chapter, we might also zoom out to the broad category of corrections, glosses, and emendations in manuscripts. To what extent does the print-to-manuscript transmission which is the primary subject of this book differ from the manuscript-to-manuscript transmission of textual details such as corrections, or from the emendations readers might make spontaneously as they read? While the proclivity (or at least the potential) to correct presents a compelling example of continuity in the reading of Chaucer across manuscript and print, my discussion allows that print-to-manuscript correcting (as well as glossing or emending) possesses some distinctive features. One of these is its scale. To understand the importance of print-to-manuscript correcting, we must recognise the relative infrequence of readers’ corrections in medieval manuscripts more generally. Wakelin’s survey of correction in late medieval English manuscripts finds that while nearly all manuscripts contain some correction by readers, ‘most only have a few’.Footnote 119 While the types of textual transfers from print to manuscript documented here are not to be found in all surviving fifteenth-century Chaucer manuscripts, my research suggests that when readers did correct, gloss, or emend a text systematically they were more likely to do so based on comparison with a print than with a manuscript or their own knowledge. Taken together, their interventions expose a pattern of textual consumption and transmission which is noteworthy in itself. Crucially, these textual interventions simultaneously register outdated, difficult, or undesirable aspects of the text and work to improve upon them. The histories of reading found in medieval manuscripts preserve vital evidence of early modern attitudes to the comprehensibility and correctness of the Chaucerian text in both media. An additional feature which distinguishes the interventions studied in this chapter is precisely that movement across media, since it reveals not only what readers thought of the text itself, but of the value, authority, and reliability of the material contexts in which they were located. The readerly attention to Chaucer’s text observed in this chapter is predicated upon an appreciation of the manuscript books, whether for their beauty, the peculiarities of their writing support or scripts, their intrinsic age, or some confluence of these.

At the same time, this chapter has shown that early modern readers worried over the Chaucerian text borne in those manuscripts, and strove to rectify it. Both Chaucer’s historical distance and the availability of comparison texts, particularly newly printed ones, made his older books suitable candidates for glossing and correction. Chaucer’s oeuvre had long been haunted by the possibility of error, and his nervous literary statements about the fallibility of textual transmission – which Lerer calls a ‘poetics of correction’ – cast a long shadow over his reception.Footnote 120 Strikingly, the errata list in the 1598 Speght, a book which itself professes to have been made in haste, casts the greatest blame not on printshop practices nor on the editor or author, but on medieval scribal culture itself: ‘These faults and many mo committed through the negligence of Adam Scriuener, notwithstanding Chaucers great charge to the contrary, might haue ben amended in the text it selfe, if time had serued’.Footnote 121 Naming the figure known as Chaucer’s scribe allows the edition’s makers to adopt a sceptical posture towards medieval manuscripts and the material processes and agents by which they were created.

The problem of Chaucer’s language became, then, a bibliographical one – transmitted in old books and resolved using new books. Print’s self-promotion as the antidote to the ailments of old books is encapsulated in a vivid envoy written by poet and printer Robert Copland in 1530. Copland used a still-extant manuscript, now Bodl. MS Bodley 638, as copytext for the Wynkyn de Worde edition of the Parliament of Fowles, and took the opportunity to juxtapose the new edition with the decrepit manuscript book which the printed book intended to supersede.Footnote 122 His envoy imagines an old book ‘Layde vpon shelfe / in leues all to torne / With letters dymme / almost defaced clene’ … ‘Bounde with olde quayres / for aege all hoore & grene’. In Copland’s narrative of the restorative powers of print, Chaucer’s text is now directed to ‘ordre thy language’ and to produce on ‘snowe wyte paper / thy mater for to saue / With thylke same langage that Chaucer to the gaue / In termes olde’. Here, in Copland’s verses, as in the light-hearted rhymes on jape with which this chapter began, there is a focus on the authenticity of Chaucer’s words – ‘thylke same langage’ – and a desire to preserve the Middle English as Chaucer meant. In both accounts, it is print that can ‘saue’ Chaucer’s words from destruction and obscurity. Copland’s envoy and the folio editions alike asked their readers to believe in the convenient fiction that the new book is, as Gillespie puts it, ‘a recovery of all that is good from the literary past’.Footnote 123 That desire for ‘termes olde’ jars with the desire for innovation, for bibliographic novelty, for the books that declare themselves on their title pages to be ‘newly printed’. The early modern editions embody some of these contradictions. Simon Horobin’s work has shown that as early as Caxton, printers deliberately retained certain archaisms to preserve or embellish ‘marked Chaucerian linguistic forms’. Thynne, for example, both modernised and selectively reprinted archaisms in Chaucer’s printed language; by some measures (particularly Chaucer’s third-person pronouns hem and her for them and their) his edition contains more archaism than those of his predecessors de Worde and Pynson.Footnote 124 That ideal of an archaic Chaucerian English is also apparent in black letter’s persistence as the typeface of choice for printing the Middle English texts in the Workes until the eighteenth century. Even as they assumed such markers of textual antiquity, these printed books bemoaned the obscurity in which Chaucer’s texts existed before the advent of print.