Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Biography of Claude III Audran (1658–1734)

- 2 The French Arabesque as an Art Form, Audran as Master Ornamentalist , and His Initial Commissioned Works

- 3 Claude III Audran and Jean de La Fontaine’s Fables: Maintaining the Social Hierarchy

- 4 Attracting New Patrons in the Eighteenth Century

- 5 Claude III Audran’s Competitors and His Legacies

- Color Plates

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

4 - Attracting New Patrons in the Eighteenth Century

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 May 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Biography of Claude III Audran (1658–1734)

- 2 The French Arabesque as an Art Form, Audran as Master Ornamentalist , and His Initial Commissioned Works

- 3 Claude III Audran and Jean de La Fontaine’s Fables: Maintaining the Social Hierarchy

- 4 Attracting New Patrons in the Eighteenth Century

- 5 Claude III Audran’s Competitors and His Legacies

- Color Plates

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Abstract

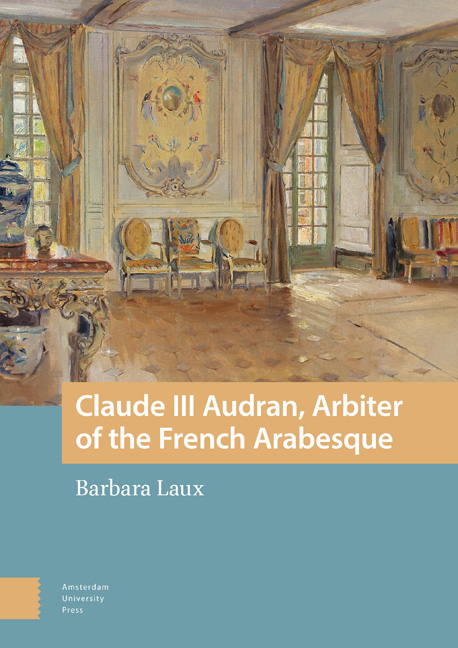

During the Régence, the nobility left Versailles and flocked back to Paris, constructing new grand townhouses that required interior decoration. For these commissions, Audran combined venerable motifs with those from popular culture suited to each patron. For Louis de Béchameil, marquis de Nointel (1630–1703), Audran and his then assistant Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) painted a ceiling and panels with singerie and made reference to Momus, god of satire, and the Régiment de la Calotte, a French secret society. For other patrons, such as the comtesse de Verrue, Jeanne-Baptiste d’Albert de Luynes (1670–1736) and Abraham Peyrenc de Moras (1686–1732), Audran customized designs to suit their taste and collecting habits. Contemporary sources add to the description and reception of these commissions.

Keywords: Régiment de la Calotte; Singerie; Momus; Château de La Muette; Hôtel de Peyrenc de Moras

While Claude III Audran's arabesques took some cues from grotesques found on the walls of the Domus Aurea, they often departed sharply from the ancient model. His continued success stemmed from his expertise and ability to bring fresh ideas to the delight of his patrons. Rather than seek historic revival of ancient designs, Audran's patrons followed the trends in the arabesque that were developed for royal residences. The nouveaux riches among them hoped to affirm their own wealth and taste by adopting forms favored by those who were more firmly established.

Satisfying the refined taste of patrons such as the duc de Vendôme, the Dauphin and especially Louis XIV imparted an elite status to Audran's work because these patrons belonged to the hereditary nobility that boasted lineage dating from the fifth century. Their pedigree assured their high social status and assumed the cultivation of inherent virtue and the continuation of notable achievements as a birthright. Special privileges accorded to the nobility and their possession of wealth fostered a high degree of prestige and independent power, which threatened the young Louis XIV during the Fronde uprising. As a consequence, the King assiduously sought to exclude the hereditary nobility from the government in order to wrest political power from them, thus decreasing their ability to challenge the monarchy.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Claude III Audran, Arbiter of the French Arabesque , pp. 147 - 178Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2024