Introduction

In this chapter, we provide an update on the distribution and abundance of the African buffalo at the scale of the entire African continent. For this purpose, we conducted a literature search to uncover published information. We also carried out an extensive survey of national and international agencies and field experts in the 37 countries that are within the buffalo’s distribution range.

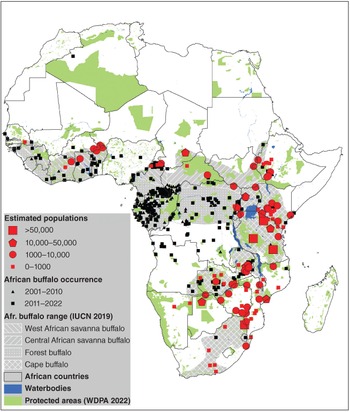

We collected abundance data from 163 protected areas or protected area complexes for the period 2001–2021. These data are mainly based on aerial counts using standardized methods, and occasionally on estimates provided by experts. We also obtained information on the presence of buffalo in 711 localities (inside and outside protected areas) for the period 2001–2021. These data and metadata were compiled in a database that is available upon request (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023).

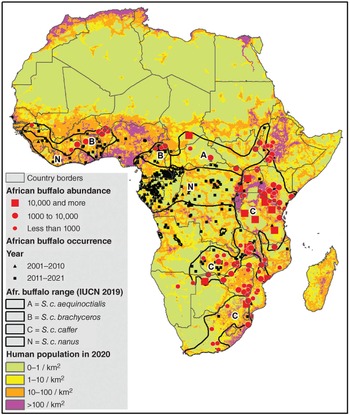

We present the distribution and abundance of each of the four subspecies of African buffalo. We are naturally aware that the validity of the ‘subspecies’ concept is under debate, and we refer to Chapters 2 and 14 for a discussion about the number of subspecies and their status. For the sake of consistency with earlier studies on buffalo distribution (East, Reference Dupuy1998; Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Korte, Melletti and Burton2014), our results are presented in accordance with the latest IUCN subspecies range (IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group, 2019). Therefore, maps of this chapter reproduce the geographical boundaries of the four subspecies published by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group, 2019). Although clearly delineated on paper, the boundaries between subspecies’ distribution ranges are in fact blurry on the ground. In case of inconsistency or doubt about the assignment of a population to a ‘subspecies’ (especially in transitional areas), we explicitly acknowledge this in the text.

Historical Distribution

Endemic to the African continent, the buffalo is one of the most successful mammals in terms of geographical distribution, abundance and biomass. Its range covers almost all natural ecosystems south of the Sahara. It mainly inhabits savannas with high herbaceous biomass, but also occupies dry shrubland as well as grassy clearings in dense tropical rainforests, and can live at altitudes above 2500 m, such as in Aberdare National Park in Kenya. The African buffalo penetrates arid biomes where surface water is permanently available. Overlaying the African buffalo’s current continental range with mean annual rainfall (Figure 4.1) shows that 95 per cent of the buffalo’s range comprises areas with more than 450 mm of rainfall (min: 150 mm; max: 4000 mm).

Figure 4.1 African buffalo distribution range in relation to average rainfall for 1970–2000.

African buffalo formerly occupied the entire savanna zone stretching between Senegal, Gambia and Guinea and Ethiopia and Eritrea, and from there south to the Cape of Good Hope, with the exception of drylands. African buffalo did not colonize islands such as Zanzibar or Mafia, although they did colonize Bioko Island (Equatorial Guinea), from where they were extirpated sometime between 1860 and 1910 (Butynski et al., Reference Butynski, Schaaf and Hearn1997).

There is no palaeontological evidence of the presence of the African buffalo in North Africa or the Nile Valley to the north of Khartoum (Prins and Sinclair, Reference Prins, Sinclair, Knight, Kingdon and Hoffmann2013). In North Africa, the aurochs (Bos primigenius; wild ancestor of domestic cattle) occupied a similar niche (Gautier, Reference Funston, Henschel and Petracca1988), perhaps preventing the buffalo’s spread to the north. Buffalo could have expanded their range in eastern and southern Africa during the last ice age due to the extinction of possible competitors, such as Pelorovis antiquus and Elephas reckii (for more details on evolution see Chapter 2; Klein, Reference Klein1988, Reference Klein1994; Prins, Reference Prins1996).

Present Distribution

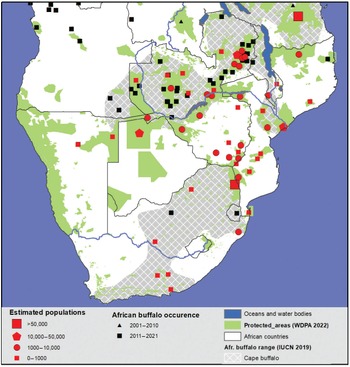

In areas of high human densities, people and their activities caused large discontinuities to arise in the historical distribution of African buffalo (Figure 4.2). Although according to our estimates its population remains above 500,000 individuals, and has been above that level since at least the last human generation (East, Reference Dupuy1998; Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Korte, Melletti and Burton2014), the species’ distribution range has been severely reduced since the nineteenth century. As there were no reliable estimates of its total population prior to the assessment undertaken by East (Reference Dupuy1998), we cannot determine whether the current population is smaller than that which existed prior to the Great Rinderpest epidemic of the 1880s (e.g. Prins, Reference Prins1996; Prins and Sinclair, Reference Prins, Sinclair, Knight, Kingdon and Hoffmann2013). The shrinkage of the species’ range was the result of the combined effects of anthropogenic impacts such as rangeland conversion, poaching, disease outbreaks and political unrest, and climatic events such as droughts. At present, most savanna populations (i.e. the three subspecies except S. c. nanus) are confined to protected areas (including trophy hunting areas).

Figure 4.2 Continental distribution and abundance of African buffalo. The two classes of occurrence (2001–2010 and 2011–2022) refer only to the date of the source and do not signify a change in status between classes. Note that in certain other chapters of this book, the West African savanna buffalo and the Central African savanna buffalo are considered together and are referred to as the ‘Northern savanna buffalo’.

Since the nineteenth century, the expansion of livestock has gradually generated direct competition for space and resources and has led to large and destructive epidemics in African buffalo populations. Exotic rinderpest was historically the most devastating disease for buffalo populations throughout Africa, leading to extreme reductions in population densities and local extinctions. The most severe population collapse occurred in the 1890s, with mortality rates estimated at 90–95 per cent across the continent (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair1977; Prins and van der Jeugd, Reference Prins and Jeugd1993; Winterbach, Reference Winterbach1998). This was followed by other episodes throughout the twentieth century. The World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly OIE) declared rinderpest eradicated in Africa in 2011 (last case reported in 2001). Rinderpest was the first animal disease to have been globally eliminated, and the second disease after human smallpox to have been globally eradicated. Both diseases are caused by viruses. During the twentieth century, efforts to limit the transmission to cattle of several pathogens, such as foot and mouth disease (FMD) and trypanosomiasis (Taylor and Martin, Reference Taylor and Martin1987), also actively reduced the geographic distribution of buffalo in several countries due to large-scale culling operations and the erection of veterinary fences.

Outright competition for range use and overexploitation by all sorts of poachers including local pastoralists also were important drivers behind the degradation of the buffalo’s status (e.g. Prins, Reference Prins1992; Prins and De Jong, Reference Prins, De Jong, Kiffner, Bond and Lee2022; Scholte et al., Reference Scholte, Pays and Adam2022).

Recent climate fluctuations, such as the droughts that affected Sahelian and Sudanese regions at the end of the 1960s and southern Africa in 1992 (Dunham, Reference Douglas-Hamilton, Froment, Doungoube and Root1994; Mills et al., Reference Mills, Biggs and Whyte1995; Chapter 8), have also strongly affected buffalo populations over the past few decades. Finally, yet importantly, armed conflicts, the feeding of armies and labourers during peacetime, the traffic of weapons and the bushmeat trade have strongly contributed to the reduction of buffalo populations in some areas (e.g. Prins et al., in review).

West African Savanna Buffalo (S. c. brachyceros)

In the 1970s and 1980s, this subspecies still locally occurred in Sahelo-Sudanian savannas and gallery forests, including those found in south-eastern Senegal, northern Côte d’Ivoire, southern Burkina Faso, Ghana, northern Benin, the extreme south of Niger, Nigeria (very locally), the northern part of Cameroon and Central African Republic (west of Chari River) (East, Reference Dupuy1998). It is worth noting that the West African savanna buffalo (Figure 4.3) was (and still is) therefore also found in Central Africa, which underlines the inconsistency of this appellation (Figures 4.4 and 4.6).

Figure 4.3 West African savanna buffalo in W National Park, Niger.

Figure 4.5 Central African savanna buffalo in Zakouma National Park, Chad.

Presently, most known populations remain in five main strongholds. Two of these are complexes hosting national parks (NP) and neighbouring trophy hunting areas: (1) W–Arly–Pendjari NPs (WAP) in Burkina Faso–Benin–Niger; and (2) Bouba N’djidda–Bénoué–Faro NPs in Cameroon. The remaining three strongholds are single NPs: (3) Niokolo-Koba NP in Senegal; (4) Comoé NP in Côte d’Ivoire; and (5) Mole NP in Ghana. In the other protected areas of the above-mentioned countries, and in Nigeria, Togo and Sierra Leone, the presence of buffalo is limited to a few scattered residual populations. At present, the populations in the remaining strongholds are isolated from each other and the distribution of the West African savanna buffalo has shrunk overall. A positive finding emerging from our investigation is that the buffalo populations inside four of these five strongholds are, when compared with 2013 figures, either constant (Niokolo-Koba NP) or increasing (Comoé NP, WAP complex, Mole NP). On the downside, the populations in Northern Cameroon appear to be decreasing.

Central African Savanna Buffalo (S. c. aequinoctialis)

This subspecies still locally populates Central African countries within the Sahelo-Sudanian savannas and gallery forests: southeast Chad, northern Central African Republic (east of Chari River), northern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), south-east Sudan and western Ethiopia (Figures 4.5 and 4.6). The subspecies is now extinct in Eritrea. Most presently known populations remain in two main strongholds: Zakouma NP in Chad and Garamba NP in DRC. In Ethiopia, the decline of several populations has been offset by the recent discovery of several populations outside the known range (see Ethiopia section below).

Forest Buffalo (S. c. nanus)

The distribution range of the forest buffalo comprises two separate regions in West and Central Africa (Figures 4.4, 4.6 and 4.7). In West Africa, fragmented and isolated populations persist in the relict rainforest belt, while the population’s stronghold is located in the Central African countries of the Congo Basin (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Korte, Melletti and Burton2014; IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group, 2019). In the Congo Basin, forest buffalo occur in the south of the Central African Republic, western Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, southern Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

Figure 4.7 Forest buffalo in Odzala National Park, The Republic of Congo.

In West Africa, the subspecies persists in Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone (see below). Forest buffalo are highly associated with forest clearings and riverine forests (Prins and Reitsma, Reference Prins and Reitsma1989; Blake, Reference Blake2002; Melletti et al., Reference Melletti, Penteriani and Boitani2007, Reference Melletti, Penteriani, Mirabile and Boitani2008; Bekhuis et al., Reference Bekhuis, De Jong and Prins2008; Korte, Reference Bekhuis, de Jong and Prins2008a). In several poorly explored areas, gaps remain in the scientific knowledge of the distribution and status of forest buffalo.

Contrary to the savanna buffalo, recent estimates of the population size of forest buffalo are available only for a few areas in the Congo Basin and their accuracy is low. Indeed, unlike aerial surveys carried out in savanna areas, surveys methods in forest environment are currently unable to provide reliable population estimates. Such estimates may become available for a larger number of sites once more appropriate techniques are implemented, such as distance sampling via camera traps, capture–mark–recapture methods using genetic fingerprinting, and methods to formally capture information from local experts (e.g. indigenous people and local communities living in the rainforests).

Cape Buffalo (S. c. caffer)

The Cape buffalo’s range encompasses East and Southern Africa and covers 17 countries (Figures 4.6, 4.8 and 4.9). In East Africa, Cape buffalo populations occur in southwestern Ethiopia, southern Somalia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi. In southern Africa, this subspecies is distributed in Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, south-west Angola, north-east Namibia, northern Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa. The current population in Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland) was reintroduced after extirpation.

(a) Cape buffalo in Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Tanzania.

(b) Cape buffalo in Okavango Delta (Botswana).

Abundance Per Country

West Africa

Burkina Faso

West African savanna buffalo formerly occurred widely in the open woodlands of the Niger basin and southern districts (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965; East, Reference Dupuy1998). Starting from the 1980s, the population has been restricted to the southernmost areas of the country. At the national level, the buffalo population comprises around 6000 individuals. Their presence is recorded in six different localities, all conservation areas (national park, protected forest, game ranch or trophy hunting area). The largest populations are located in the eastern conservation areas: Arly complex with about 4950 individuals (0.5 ind./km²) and W Burkina Faso complex with about 300 animals (0.8 ind./km²) (Ouindeyama, Reference Ouindeyama, Chevillot and Akpona2021). The presence of buffalo is reported in central and western conservation areas (Nazinga Game Ranch, Bougouriba, Comoé-Lareba and Tuy Mouhoun areas) but in very low densities and isolated populations (Dahourou and Belemsobgo, Reference Cumming2020). In Nazinga Game Ranch, the total population is around 150 individuals (PAPSA, 2018).

After a period of growth between 2003 and 2015 (from ~4800 to ~8900 individuals; Bouché et al., 2003, Reference Bouché, Nzapa Mbeti Mange and Tankalet2015), buffalo populations of eastern conservation areas recently faced a strong population decline (~5300 individuals; Ouindeyama et al., Reference Ouindeyama, Chevillot and Akpona2021). Due to the severe worsening of the security situation, the protected areas are facing an increase in threats of banditry, adding new forms of violent interactions with protected area management teams.

Côte d’Ivoire

West African savanna buffalo formally occurred throughout the northern region (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965; East, Reference Dupuy1998), but their populations have collapsed and are now isolated in a few protected areas. The main population is located in Comoé NP with an estimated 1450 individuals (0.1 ind./km²; OIPR, 2019), which has increased slightly since 2010 (then about 900 individuals; N’Goran et al., Reference N’Goran, Maho and Kouakou2010) and 2016 (1200 individuals; Bouché, Reference Bouché, Frederick and Kohi2016). The presence of buffalo has been recorded in Lamto and Marahoué NPs, but their numbers were not reported and are thought to be very low. Interestingly, a population of about 300 individuals was reported in N’Zi River Lodge Voluntary Nature Reserve near Bouaké (2.1 ind./km²) and is known to be growing (Louis and Karl Diakité, personal communication, 2021).

The few observations of the forest buffalo subspecies are reported from the residual blocks of forest in the south of the country. This holds especially for Tai NP, where transect counts gave an estimated population size of ~500 individuals (0.09 ind./km²) in 1999–2004, with lower estimates based on transect dung counts of ~200 individuals (Hoppe-Dominik et al., Reference Holubová2011). In striking contrast, recent detailed surveys only reported indirect signs, suggesting a collapse of the buffalo population (Tiedoue et al., Reference Tiedoue Manouhin, Kone Sanga, Diarrassouba and Tondossama2019, Reference Tiedoue Manouhin, Diarrassouba and Tondossama2020).

Between 2019 and 2021, a wildlife survey on foot was conducted throughout Côte d’Ivoire (ONFI, 2021). The data from this survey for African buffalo came mainly from indirect observations (tracks and dung) for which the risk of confusion with livestock was considered high (Gilles Moynot, ONFI, personal communication), and therefore are not included here.

Benin

West African savanna buffalo ranged in the past throughout the northern region (East, Reference Dupuy1998), but populations are now restricted to Pendjari and W-Benin complexes (both complexes include the eponymous NPs and surrounding trophy hunting areas). The Pendjari complex has an estimated population of about 7200 individuals (1.2 ind./km²), while in the W-complex some 1500 buffalo were counted (0.2 ind./km²; Ouindeyama et al., Reference Ouindeyama, Chevillot and Akpona2021). The three main aerial surveys conducted over the last two decades in northern Benin show that buffalo populations have doubled since the early 2000s (2003: ~4600 individuals; 2015: ~8200 individuals; 2021: ~8650 individuals; Bouché et al., 2003, Reference Bouché, Nzapa Mbeti Mange and Tankalet2015; Ouindeyama et al., Reference Ouindeyama, Chevillot and Akpona2021).

Records of forest buffalo mainly refer to old observations located in the centre and southern sectors of Benin (PAPFCA, 2007; Sinsin et al., Reference Sinsin, Kampmann, Thiombiano and Konaté2010). The last observations of forest buffalo were reported during a ground survey carried out in the Forest of Agoua (Central Benin) in 2013 in which about 100 individuals scattered over 12 herds were seen (Natta et al., Reference Natta, Nago and Keke2014). Further investigation is needed because buffalo are regularly observed in several spots in the southern and central parts of the country (Félicien Amakpe, personal communication).

Gambia

No recent information was received from this country. To our knowledge, the West Africa savanna buffalo subspecies is now extinct in Gambia (Jallow et al., Reference Jallow, Touray, Jallow, Chardonnet and Chardonnet2004).

Ghana

Buffalo formerly occurred throughout Ghana, with the West African savanna buffalo in the northern and eastern savannas, and the forest buffalo in the southwestern forests (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965; East, Reference Dupuy1998). The species is now restricted to a few protected areas.

The major surviving population of the savanna buffalo occurs in Mole NP with an estimated 1400 animals (0.3 ind./km²; Hauptfleisch and Brown, Reference Grossmann, Lopes Pereira and Chambal2019), and an increasing trend during the last decade (from about 700 individuals: Bouché, Reference Bouché2006). Small populations persist in the following savanna protected areas: Bui National NP (~60; 0.03 ind./km²), Yerada–Kenikeni Forest Reserve (~30; 0.03 ind./km²), Kyabobo NP (~50; 0.1 ind./km²), Digya NP (~120; 0.03 ind./km²) and Bomfobiri Wildlife Sanctuary (~30; 0.6 ind./km²) (David Kpelle, Ghana Forestry Commission, personal communication). Some individuals also have been spotted in the Kogyae Strict Nature Reserve (Danquah et al., Reference Dandena and Dinkisa2015) and Kalakpa Reserve (Afriyie et al., Reference Afriyie, Asare, Danquah and Pavla2021).

The status of the forest buffalo is unclear. Its presence was reported in Subri River Forest Reserve in 2011 (Buzzard and Parker, Reference Buzzard and Parker2012), but more recent information does not exist.

Guinea

African buffalo once occurred widely, with the West African savanna buffalo in the north intergrading to the forest buffalo in the south-west and south-east. It has been eliminated in most of its former range by overhunting and habitat destruction (East, Reference Dupuy1998) and remains in pockets of relict populations spread throughout the country. The savanna buffalo is known to be present in Haut Niger NP (Nefzi, Reference Nefzi2020) and Moyen-Bafing NP (Wild Chimpanzee Foundation, 2021); however, without numerical information. Forest buffalo is present in Ziama Biosphere Reserve, the largest primary rain forest of the country, next to Liberia (Nefzi, Reference Nefzi2020). It has also been observed recently in Tokounou, Tiro and Nialia subprefectures (Catherine André, personal communication), but no numerical estimates are available. However, we suspect that both savanna and forest subspecies may be present elsewhere in the country.

Guinea-Bissau

Intermediate forms between the West African savanna buffalo and the forest buffalo formerly occurred widely in the forest–savanna mosaic of Guinea-Bissau (East, Reference Dupuy1998). The species still occurs widely in the south and is reasonably common in some areas, for example Cufada Lagoons Natural Park, Cantanhez Forest (da Silva et al., Reference Danquah and Owusu2021) as well as Boe Region (Coppens, Reference Cockar2015), but no numerical estimates are available. No information was found from the northern part of the country.

Liberia

Only forest buffalo are known to occur in Liberia. In this country, the African buffalo was reported to occur sparsely in the 1960s (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965). A national survey carried out in 1989/1990 recorded the presence of the species in poorly accessible and high-altitude forests of the south-east and north-west (Anstey, Reference Anstey1991 cited by East, Reference Dupuy1998). The contraction of its distribution range in recent decades appears to be due to civil war, unrest and widespread poaching. We have no recent information on its status, except observations by camera traps in the Grebo-Krahn NP forest in 2020 (Wild Chimpanzee Foundation; www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtYUSk53p2Q).

Niger

In the early twentieth century, West African savanna buffalo occurred in the south-western tip of Niger (Niger River basin and along parts of the Nigeria border; East, Reference Dupuy1998). It has since disappeared from most of its former range and survives only in the W-Niger complex (W-NP and Tamou Total Reserve), where the last population estimate was about 350 individuals (0.1 ind./km²; Ouindeyama et al., Reference Ouindeyama, Chevillot and Akpona2021). A comparison with aerial counts conducted over the past two decades suggests a strong reduction in numbers since 2015 (2003: ~1200 individuals; 2015: ~1100 individuals; 2021: ~350 individuals; Bouché et al., 2003, Reference Bouché, Nzapa Mbeti Mange and Tankalet2015; Ouindeyama et al., Reference Ouindeyama, Chevillot and Akpona2021).

Nigeria

In the early twentieth century, the African buffalo was reported to be very common throughout Nigeria, from coastal evergreen forests (forest buffalo subspecies) to shrubby savannas in the north of the country (savanna buffalo subspecies). During the 1960s, the same author reports its occurrence in all suitable habitats, except for the southern coastal districts (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965). In the late twentieth century, East (Reference Dupuy1998) reported populations reduced to small, generally declining populations in a few protected areas.

For the West African savanna buffalo, the findings reported by East in 1999 still apply in 2022. The subspecies maintains an extremely limited distribution in northern Nigeria with a presence recorded only in three sites that are far from each other: Yankari Game Reserve, Kainji Lake NP and Gashaka Gumti NP (Andy Dunn, Naomi Matthews and Stuart Nixon, personal communication). The prospects for restoring the populations of Kainji Lake NP are poor due to their isolation from other populations and to the insecurity prevailing when this book went to press. Gashaka Gumti NP borders Faro NP in Cameroon, where about 600 individuals were estimated to occur (Elkan et al., Reference Elizalde, Elizalde and Lutondo2015). A transfrontier conservation strategy could pave the way for the restoration of a viable buffalo population in Gashaka Gumti NP when the political and security contexts on both sides of the border so allow.

The forest buffalo was once widespread in most southern areas of Nigeria (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965), but has been eliminated from most of its former range and reduced to small, generally declining populations in a few protected areas (East, Reference Dupuy1998). To date, this subspecies seems mainly localized in Cross River NP (4000 km2), where presence was reported from 2001 to 2019 (Eniang et al., unpublished data; Eniang et al., Reference Elkan, Vanleeuwe and Eldar2017; Bassey, Reference Bassey2019). In this NP bordering Cameroon, only 131 records of forest buffalo were reported for all years combined during line transect surveys (namely, in 2001, 2005, 2009, 2013; Eniang et al., Reference Elkan, Vanleeuwe and Eldar2017). Only one forest buffalo observation was reported in the Mbe Mountains corridor (linking the Afi Mountain Wildlife Sanctuary and the Okwangwo Division of Cross River NP) during a 2019 year-round anti-poaching patrol (Eban, Reference East2020). Buffalo presence was recently reported in Okomu NP in south-central Nigeria (Akinsorotan et al., Reference Akinsorotan, Odelola, Olaniyi and Oguntuase2021). In other words, the forest buffalo is near to extinction in Nigeria.

Senegal

West African savanna buffalo were formerly widespread in the southern savannas of this country (East, Reference Dupuy1998). The Senegalese buffalo population seems to have been isolated from other populations for some time (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965). Nowadays, populations have drastically declined and most buffalo are now only located in Niokolo–Koba NP. This protected area, where buffalo populations reached about 1000 individuals in the late 1960s (Dupuy, Reference Dunham and Westhuizen1971) now hosts about 500 buffalo (0.06 ind./km²; Rabeil et al., Reference Rabeil, Hejcmanová and Gueye2018). These figures are quite similar to those observed 12 years earlier (~500 individuals (0.05 ind./km²), Renaud et al., Reference Renaud, Gueye and Hejcmanová2006). Some buffalo are present in the private fenced reserves of Bandia (ranging from 80 to 134 individuals; 3 ind./km²; Raymond Snaps, personal communication; Holubová, Reference Hickey, Granjon and Vigilant2019) and Fathala (40; 1.7 ind./km²; Holubová, Reference Hickey, Granjon and Vigilant2019). The Bandia buffalo originated from 10 individuals translocated from Niokolo–Koba NP in 2000. It is worth noting that a relict population of savanna buffalo can still be found in the Faleme trophy hunting area (Philippe Chardonnet, personal communication).

Sierra Leone

Forest buffalo may still have occurred until a decade ago, mainly in the north of the country in 2009 and 2010 (Brncic et al., Reference Brncic, Amarasekaran and McKenna2015). No recent information is available from this country.

Togo

Until the mid-1950s, the African buffalo was found in most parts of the country (Baudenon, Reference Baudenon1952). Although classified as West African savanna buffalo, this author observed an important morphological gradient across the country, with black-coated buffalo in the north and red-coated buffalo in the south. According to East (Reference Dupuy1998), African buffalo survived in small to moderate numbers in the country’s protected areas until the early 1990s, but were expected to be close to extinction in the late 1990s.

From our investigations, it appears that African buffalo are still present in small numbers in several protected areas. In the two northern regions (Savanne and Kara), small populations were reported in Oti–Kéran NP (MERF, 2013) and Djamdè Faunal Reserve (MERF, 2014). In the Central Region, observations were made in Fazao–Malfakassa NP (Atsri et al., Reference Atsri, Adjossou and Tagbi2013) and Abdoulaye Game Faunal Reserve (MERF, 2017). Further south in the Plateaux Region, Amou Mono classified forest (MERF, 2016) and Togodo complex of protected areas (GIZ, Reference Gedow, Leeuw and Koech2017) also host small numbers.

Central Africa

Cameroon

Buffalo formerly occurred more or less throughout the country, except for the more arid parts of the far north (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965), with the West African savanna buffalo in northern and central Cameroon and the forest buffalo in the southern forests, which cover about half the country’s area (East, Reference Dupuy1998). In Cameroon, the savanna buffalo is now restricted to conservation areas in the North Region. In contrast, the forest buffalo is still present in forest areas sparsely populated by humans, especially in the South and East provinces, and to a lesser extent in the south-west province.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, West African savanna buffalo used to be common in the Logone floodplain, Far North Cameroon. However, in 1935, the African buffalo was already rare in the area, and no longer occurred when Waza NP was created in 1968 (Scholte, Reference Scholte2005). Remaining buffalo are located in the Bouba Ndjidda–Bénoué–Faro complex (North Province) with an overall estimated number of 2500 individuals (0.11 ind./km²; Elkan et al., Reference Elizalde, Elizalde and Lutondo2015 for Bénoué and Faro; Grossmann et al., Reference Gouteux, Blanc and Pounekrozou2018 for Bouba Ndjidda). It is hard to evaluate the proportion of animals within national parks or trophy hunting areas, but the last surveys (2015, 2018) tend to show that Bouba Ndjidda and Faro NPs still host buffalo, while for Bénoué, all individuals were spotted in the trophy hunting areas and none in the national park. The general trend seems to show a decrease in the population, estimated at 4000 individuals in 2008 (0.18 ind./km²; Omondi et al., Reference Omondi, Bitok, Tchamba and Lambert2008).

Over the past 15 years, the presence of the forest buffalo was reported in most of the protected areas and numerous logging concessions.

In south-west and north-west provinces (border with Nigeria), buffalo are present in Korup NP (Astaras, Reference Astaras2009) and were also sighted in a logging concession located north of the park. Further north, buffalo presence was reported in the Black Bush Area of Waindow in 2014 (Chuo and Angwafo, Reference Christy, Lahm, Pauwels and Weghe2017). These buffalo populations appear to be more scattered and isolated as they are surrounded by areas of high human population density. In this respect, it should be noted that no observations of buffalo have been reported recently in the West, Littoral and Central provinces, all of which are heavily populated. However, it is plausible that buffalo populations remain in the northern part of Central Province in the triangle formed by the Mpem-Djim, Mbam-Djerem, and Deng-Deng NPs. The presence of buffalo was observed there in a logging concession in 2004 (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023).

In the South province, buffalo are present in Campo–Ma’an NP (650 km2), where population sizes were estimated by Bekhuis et al. (Reference Bekhuis, de Jong and Prins2008) with 20 individuals only (densities 0.01–0.04 ind./km2) and by Van der Hoeven, de Boer and Prins (Reference Hoeven, Boer and Prins2004) at 0.07–1.27 ind./km2. The presence of buffalo was also reported in several logging concessions located on the periphery of the park (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023). Further east, forest buffalo also were reported in a logging concession located north of Mangame Wildlife sanctuary.

In the south-eastern end of the country (East Province), forest buffalo are present in Dja Biosphere Reserve (Bruce et al., Reference Bruce, Wacher and Ndinga2017, Reference Bruce, Amin and Wacher2018) and have been sighted in several logging concessions located south of the reserve over the past 15 years (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023). Forest buffalo were reported in Nki and Boumba-Bek NPs in 2015 (Imbey et al., Reference Imbey, Mbezele and Ahanda2019; Ngaba and Tchamba, Reference Ngaba and Tchamba2019; Hongo et al., Reference Hoeven, Boer and Prins2020) and Lobeke NP (Gessner et al., Reference Gautier2013). The area surrounding these three protected areas is almost entirely allocated to logging. The presence of buffalo also has been reported in many logging concessions over the past 15 years (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023).

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR) is the only country where three subspecies of buffalo occur.

The West African savanna buffalo subspecies used to be widespread in the west of the country next to the border with Cameroon, although its West African name looks odd in a Central African country. Nowadays, information is lacking about this subspecies in CAR, but it is certainly and by far the least represented of the three subspecies present in CAR. It may be reasonable to think that buffalo are present next to the Cameroon border because there are Trophy Hunting Areas (Zones d’Intérêt Cynégétique) on the Cameroon side with buffalo quota and offtake.

Central African savanna buffalo were historically widespread in all Central African savannas (East, Reference Dupuy1998). Presently, residual buffalo populations are apparently restricted to the far Northern complex (Bamingui–Bangoran and Manovo–Gounda St Floris NPs and surrounding trophy hunting areas) and in the Southeast complex (Chinko Basin).

In the Northern complex, the population numbers declined from ~19,000 individuals (0.3 ind./km²) in 1985 (Douglas-Hamilton et al., 1985) to ~13,000 (0.2 ind./km²) in 2005 (Renaud et al., Reference Renaud, Fay and Abdoulaye2005), after which it collapsed to 13 individuals only in 2017 (Elkan et al., Reference Elkan, Mwinyihali and Mendiguetti2017). Given the level of insecurity in the region, it may have now gone extinct.

In the Southeast complex, buffalo populations strongly declined between 2012 and 2017 due to the invasion of the area by transhumant herders from South Darfur, Sudan (Aebischer et al., Reference Aebischer, Ibrahim and Hickisch2020). Conservation efforts undertaken by African Parks since 2014 have reversed the trend in the Chinko conservation area (6000 km2), where the buffalo population was estimated at over 4000 buffalo in 2022 (Thierry Aebischer, personal communication).

The huge uninhabited wilderness areas in between those residual complexes are composed of trophy hunting areas where buffalo were present and hunted before the 2012 war started. However, no recent information on buffalo presence or abundance is available.

Although a large part of potential suitable areas has not been surveyed recently, the conservation status of the Central African savanna buffalo should be considered as under major threat in the Central African Republic (see also Scholte et al., Reference Scholte, Pays and Adam2022).

Forest buffalo are mainly localized in the south-west tip of the country, covered by rainforests. Over the past 15 years, the presence of the forest buffalo was reported in all protected areas and most of the logging concessions of this region (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023). Buffalo are encountered in the Dzanga-Sangha Protected Area complex, including recent records in the Special Reserve of Dzanga-Sangha (Melletti et al. Reference Melletti, Penteriani and Boitani2007 Beudels‐Jamar et al., Reference Beudels‐Jamar, Lafontaine and Robert2016). Forest buffalo were also reported from the south-east part of the country, where forest and savanna intermingle: Bangassou forest (Roulet, Reference Roulet2006) and the thick riverine forests of the upper Mbomou River (Philippe Chardonnet, personal communication).

Chad

Central African savanna buffalo were formerly widespread in the south of the country from Lake Chad to Salamat (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965). However, buffalo were extirpated from most of their original range by agricultural and livestock expansions as well as drought (East, Reference Dupuy1998). The largest population, estimated at ~15,500 individuals (5 ind./km²), is located in Zakouma NP (Fraticelli et al., Reference Fonteyn, Vermeulen and Deflandre2021). In this protected area, the buffalo population tripled in 15 years, showing an average annual growth rate of 7 per cent. In January 2022, 905 buffalo were translocated from Zakouma NP to restock the nearby Siniaka-Minia wildlife reserve (Naftali Honig, personal communication).

The last survey in Sena Oura NP did not encounter any buffalo (Elkan et al., Reference Elizalde, Elizalde and Lutondo2015). Some buffalo were reported in the far south province of Logone Oriental near Monts de Lam and Baïbokoum in 2021 (Matuštíková, Reference Matuštíková2021), suggesting that buffalo populations of Bamingui-Bangoran/Manovo-Gounda St Floris in the Central African Republic and of Bouba N’djidda complex in Cameroon could have some connection through southern Chad.

Democratic Republic of Congo

Forest buffalo seem to be widespread in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC; informally known as ‘Congo-Kinshasa’), but with a patchy distribution because DRC is one of the most densely populated countries in the Congo Basin. This may be due to a combination of both human pressure (e.g. poaching, meat harvesting for logging camps and for other extractive industries) and a lack of knowledge.

In the south-western section of the DRC forest block (Maï-Ndombe and Equateur Provinces), the presence of buffalo was reported in Tumba-Ledima Reserve (ICCN and WWF, 2016a) and Ngiri Triangle Reserve (T. Breuer, personal observation). The presence of the forest buffalo was recorded during the forest management surveys of many logging concessions over the past 15 years, particularly in the western and south-eastern parts of Mai-Ndombe Province (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023).

In the south-central section of the DRC forest block (north of Kasai and Sankuru provinces, south of Tshuapa Province), forest buffalo were recently reported in Salonga NP (Bessone et al., Reference Bessone, Kühl and Hohmann2020) and the Tshuapa–Lomami–Lualaba landscape (John Hart, personal communication). Although highly possible, the presence of buffalo was not reported (to our knowledge) from Sankuru Reserve.

In the south-east section of the DRC forest block (Maniema and South Kivu Provinces), forest buffalo were reported in Kahuzi–Biega NP (Spira et al., Reference Spira, Mitamba and Kirkby2018), Kasongo and Pangi priority areas (ICCN and WWF, 2017a), the Itombwe NR (ICCN and WWF, 2016b) and in the Luama–Kivu region (ICCN and WWF, 2017b).

In the north-central section of the DRC forest block, the presence of buffalo has been confirmed in a dozen places of Tshopo Province over the last 15 years by several studies (van Vliet et al., Reference Van Vliet, Nebesse and Gambalemoke2012; Nebesse, Reference Nebesse2016) and forest management surveys (Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023). Further west, its presence was recorded in Abumonbazi Reserve (province of Nord-Ubangi; ICCN and WWF, 2015a) and in a logging concession (‘09/11-Baulu’) located south of Lomako–Yokokala Reserve (north of Tshuapa Province; Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023).

In the eastern section of the DRC forest block, forest buffalo were reported north of Maiko NP (Naomi Matthews and Stuart Nixon, personal communication) and in the southern section of Virunga NP (Mikeno Sector; Hickey et al., Reference Hauptfleisch and Brown2019). Further north (Ituri province), buffalo were reported in Okapi Wildlife Reserve (Madidi et al., Reference Madidi, Maisels and Kahindo2019).

Interestingly, the presence of buffalo also has been reported south of the current ‘official’ (IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group, 2019) range of the forest buffalo, in trophy hunting areas: Bombo Lumene (ICCN and WWF, 2017c), Bushimaie (ICCN and WWF, 2016c), and Swa-Kibula (ICCN and WWF, Reference Houngbégnon2015b) as well as in Mangai Nature Reserve (ICCN and WWF, Reference Hoppe‐Dominik, Kühl, Radl and Fischer2015c) and Kaniama Elephant Refuge (ICCN and WWF, 2016d). The taxonomic status of these populations is unclear.

Central African savanna buffalo formerly occurred on the edge of the dense forest along the northern and eastern borders of the country (East, Reference Dupuy1998). Much hunted and regularly infected with rinderpest, buffalo populations became isolated in Garamba NP (Northern border), where Sudanese meat hunters reduced the population from 53,000 in 1976–83 to 26,000 in 1995 (East, Reference Dupuy1998). Nowadays, Garamba NP and adjacent trophy hunting areas (~14,800 km2) host about 9400 buffalo (0.6 ind./km²; Ngoma et al., Reference Ngoma, Diodio and Dieudonné2021). The population in Garamba NP may have increased slightly from some 6000 individuals in 2012 (Bolaños, Reference Bolaños2012) with improved protection of the park. Population estimates in Bili–Uere NP are unknown, but most probably low with a few small groups left (Elkan et al., Reference Elkan, Hamley and Mendiguetti2013b; Jef Dupain, personal communication, 2018).

Cape buffalo – in the east of the DRC, along the border with Uganda, the central plains of Virunga NP are host to a population of savanna buffalo located in a zone of introgression between several subspecies and which we have assigned to the ‘caffer’ subspecies. The population of Virunga NP has decreased from about 2100 individuals in 2010 (Plumptre et al., Reference Plumptre, Kujirakwinja and Moyer2010) to about 600 (Wanyama et al., Reference Wanyama, Balole and Elkan2014).

In the southern savannas, the population of Upemba NP is less well monitored, but we think it is very small as only 15 individuals were spotted in 2009 (Vanleeuwe et al., Reference Vanleeuwe, Henschel and Pélissier2009). East (Reference Dupuy1998) stated that buffalo were eliminated from the Kundelungu NP population and we have not received any contradicting information.

Equatorial Guinea

There is evidence of the former widespread occurrence of forest buffalo on Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea, but no indication of a surviving population was found during 4.5 months of field surveys there between 1986 and 1992 (Butynski et al., Reference Butynski, Schaaf and Hearn1997). Due to overhunting, buffalo were probably already extirpated from the island between 1860 and 1910.

In the mainland region of the country, the forest buffalo formerly occurred throughout Mbini (Rio Muni). It has been eradicated from parts of its range but seems to have survived locally within the remaining forested areas, including Monte Alen NP until the end of the 1990s (East, Reference Dupuy1998).

Gabon

Gabon is a sparsely populated country, 88 per cent of which is covered by equatorial forests. The country is home to a largely preserved biodiversity. Thirteen national parks were created in 2002 and protected areas cover 15 per cent of the country (41,000 km2). About half of the country (~142,000 km2) is dedicated to logging (WRI, 2013). Forest buffalo populations are widely distributed in Gabon both inside and outside protected areas, including logging and oil concessions (Prins and Reitsma, Reference Prins and Reitsma1989). Except for Akanda NP, located 30 km north of Libreville, the presence of the forest buffalo has been documented in all of the national parks over the past 15 years (Christy et al., Reference Chase, Schlossberg, Sutcliffe and Seonyatseng2008; Vanthomme et al., Reference Vanthomme, Kolowski, Korte and Alonso2013; Nakashima, Reference Nakashima2015; Hedwig et al., Reference Haurez, Petre and Vermeulen2018). For this country, we reviewed 42 reports of biodiversity inventories conducted on foot by international forestry consultancy companies in logging concessions between 2000 and 2017 (unpublished and confidential reports). Almost all of these inventories recorded evidence of buffalo presence. These observations are supported by recent surveys conducted in several logging concessions using camera traps (Houngbégnon, Reference Hongo, Dzefack and Vernyuy2015; Nunez et al., Reference Nunez, Froese and Meier2019; Fonteyn et al., Reference Fonteyn, Vermeulen and Deflandre2021; Naomi Matthews and Stuart Nixon, personal communication).

Estimates of buffalo populations were carried out in a forest–savanna mosaic area of Lopé NP (North sector 70 km2) where Korte (Reference Korte2008b) estimated about 300 individuals in 18 herds with a density of 5 ind./km2. In forest areas at Lopé NP, White (Reference White1994) estimated a density of 0.42 ind./km2. In the Réserve de Faune de Petit Loango, Morgan (Reference Morgan2007) found a density of 1.7 ind./km2. Prins and Reitsma (Reference Prins and Reitsma1989) reported a forest buffalo density of 0.51 ind./km2, but absolute numbers could not be established reliably.

Republic of Congo

Republic of Congo (informally known as ‘Congo-Brazzaville’) is a sparsely populated country, 70 per cent of which is covered by equatorial forests. The central part of the country is made up of the so-called Bateke plateaus, which are covered with savanna grassland and riverine forests.

In the northern part of the country, which is very sparsely populated, the forests of the Congolese basin are home to widely distributed buffalo populations. Forest buffalo are present in all of the protected areas: Odzala-Kokoua NP (Chamberlan et al., Reference Chamberlan, Maurois and Marechal1995), Nouabalé-Ndoki NP (Blake, Reference Blake2002), Ntokou-Pikounda NP (Malonga and Nganga, Reference Malonga and Nganga2008), and Lac Tele Reserve (Devers and Van de Weghe, Reference Devers and Weghe2006). Between these protected areas, upland forests are allocated to logging. For this area, we reviewed 10 biodiversity survey reports conducted between 2005 and 2019 by international forestry consultancy companies in 10 logging concessions (unpublished and confidential reports). All of them recorded evidence of buffalo presence. In northern Congo, Blake (Reference Blake2002) recorded densities between 0.01 and 0.04 ind./km2 at Nouabalé-Ndoki NP, while Chamberlan et al. (Reference Chamberlan, Maurois and Marechal1995) estimated the buffalo population of Odzala-Kokoua NP at around 500 individuals (0.4 ind. km2).

From the central part of the country, little information is available on the presence of forest buffalo in the savannas and gallery forests of the Bateke Plateau. However, Mathot et al. (Reference Mathot, Ikoli and Missilou2006) report buffalo presence in the Lessio-Luna Wildlife Sanctuary bordering the Lefini Reserve.

In the southern part of the country, forest buffalo are present in Conkouati-Douli NP (Devers and Van de Weghe, Reference Da Silva, Minhos and Sa2006) and Kouilou Department (Orban et al., Reference Orban, Kabafouako and Morley2018). In Niari and Lekoumou Departments, the biodiversity survey reports conducted in the logging concessions between 2005 and 2019 on foot also reported evidence of buffalo presence.

East Africa

Burundi

A resident population of cape buffalo has been living for a long time and continues to do so today in the narrow strip of Ruvubu NP, Eastern Burundi (Nzigidahera et al., Reference Nzigidahera, Mbarushimana, Habonimana and Habiyaremye2020).

Ethiopia

African buffalo populations have long been restricted to the south-western and western parts of the country, along the borders of Kenya, South Sudan and Sudan (Sidney, Reference Sidney1965). East (Reference East1998) reported that the main populations can be found in Omo and Mago NPs. Buffalo do also occur in montane forests and swampy wetlands, such as in the Chebera Churchura (Megaze et al., Reference Megaze, Balakrishnan and Belay2018) and Gambella NPs (TFCI, 2010; Rolkier et al., Reference Rolkier, Yehestial and Prasse2015). Currently their distribution is largely confined to protected areas with a total estimated population of about 15,000 (around 5000 S. c. aequinoctialis and 10,000 S. c. caffer – Table 4.1).

Ethiopia is a contact zone between the Cape buffalo and the Central African savanna buffalo where the two subspecies intergrade. The presence of intermediate phenotypes and the absence of geographical barriers make classification difficult. For the sake of consistency with earlier studies on buffalo distribution (East, Reference Dupuy1998; Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Korte, Melletti and Burton2014), our results are presented in accordance with the current IUCN subspecies range (IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group, 2019), but this is one of the areas where the ‘subspecies concept’ loses meaning for African buffalo.

The largest population of Cape buffalo is found in Chebera Churchura NP (~5200 animals; Megaze et al., Reference Macandza, Bento and Roberto2017). Significant populations are also found in other formally protected areas, such as Omo NP (~800 animals; Tola, Reference Tola2020), Mago NP (~850 animals; Tsegaye, Reference Tsegaye2020). In addition, about 2000 buffalo are estimated to be in the Tama wildlife reserve that connects Omo and Mago NPs (Girma Timer, personal communication). Finally, the Weleshet-Sala controlled trophy hunting area holds about 1100 individuals (Kebede et al., Reference Kebede, Timer and Gebre-Michael2011).

Significant populations of Central African savanna buffalo are found in Gambella NP (~1400 animals; TFCI, 2010). Reports from two newly established national parks indicate the presence of about 1700 buffalo in Maokomo Nature Reserve (Wendim, Reference Wendim2015). The presence of several hundred buffalo was also confirmed by a count in Dati Wolel NP (Gonfa et al., 2015), but the population estimate is not reliable. Buffalo observations were also recently reported from Alatash NP along the border with Sudan (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Mohammed and El Faki2018).

During the last decade, several Central African savanna buffalo populations have been reported north-east of their earlier established (IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group, 2019) distribution range. Two Controlled Hunting Areas (CHAs) hold a reasonable number of buffalo: Haro Aba Diko CHA (~900 individuals; Kebede and Tsegaye, Reference Kebede and Tsegaye2012) and Beroye CHA (~600 individuals; Kebede et al., Reference Kebede, Wendim and Abdulwahid2013). A population of at least 60 buffalo was reported in Didessa NP (Wendim, Reference Wendim2018) and a herd of seven animals was repeatedly observed in Jorgo-Wato National Forest Priority Area (Jebessa, Reference Jebessa2015; Erena et al., Reference Eniang, Ebin and Nchor2019). Finally, Lafto Forests area hosts about 340 buffalo (Dandena and Dinkisa, Reference Dalimier, Achard, Delhez, Eba’a Atyi, Hiol Hiol and Lescuyer2014). Yet we repeat that ‘subspecies’ designation in this country is shaky due to intergradation.

Kenya

The Cape buffalo was formerly widespread throughout southern and central Kenya, and on isolated, forested hills and mountains in the north. In the 1990s, the population became largely confined to protected areas, except in Laikipia and Lamu districts (East, Reference Dupuy1998). The status of buffalo in Kenya has recently been updated during a national wildlife census undertaken between April and July 2021. Several aerial total counts covered nearly 60 per cent of Kenya’s land mass (Waweru et al., Reference Waweru, Omondi and Ngene2021). Results show that the Cape buffalo is distributed in almost all of the wildlife ecosystems surveyed, except in the northern counties of Mandera, Wajir, Turkana as well as the Nasolot-Kerio Valley ecosystem. About 41,700 buffalo were counted.

In Kenya, seven conservation areas host populations of over 1000 buffalo, respectively, Maasai Mara ecosystem (~11,600), Tsavo ecosystem (~8000), Lake Nakuru NP (~6500), Laikipia–Samburu–Marsabit ecosystem (~6300), Lamu–Lower Tana and Garissa ecosystem (~3000), Meru ecosystem (~2600) and Naivasha–Nakuru ranches (~1500). These seven ecosystems account for about 95 per cent of Kenya’s total buffalo population. Three conservation areas contain a few hundred buffalo, namely Nairobi NP (~1000), Amboseli–Magadi ecosystem (~500) and Ruma NP (~400). Small populations occur in other protected areas, such as Athi–Kapiti ecosystem, Mwea National Reserve, Shimba Hills National Reserve and Oldonyo Sabuk NP. Other populations have not been estimated over the years because the technique of aerial surveys is not well suited for dense forests and nature of the terrain of Aberdares, Mount Kenya, and Mount Elgon forested areas or Forest Reserves such as Mukogodo, Ngare Ndare Arabuko Sokoke and Boni Dodori. For this reason, but also because some buffalo strongholds were not surveyed under optimal visibility conditions (e.g. Lamu–Lower Garissa and Tana River Ecosystem with about 13,800 buffalo in 2015), the above-mentioned figure for the Kenyan population of buffalo is likely underestimated.

According to the latest national census (Waweru et al., Reference Waweru, Omondi and Ngene2021), buffalo in Kenya are now largely confined to protected areas. In the Mara ecosystem, 70 per cent of all buffalo were found in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, while the remaining 30 per cent were recorded from the Maasai Mara community conservancies. In the Tsavo ecosystem, 80 per cent of the buffalo population was found inside the protected areas. In the Laikipia–Samburu–Marsabit–Meru ecosystem, 69 per cent of the population was counted in ranches, 27 per cent in the protected areas and 3 per cent in community/settlement areas.

In Kenya, buffalo populations suffered a sharp contraction in the 1990s because of severe drought and the very last rinderpest events. For example, the Mara population was reduced from 12,200 to 3100 by the 1993–94 drought (East, Reference Dupuy1998) and has since shown good recovery (~11,600 animals in 2021). The buffalo population in Nakuru NP has recovered and has consistently increased from about 2200 buffalo in the year 2000 to the current population of about 6400 individuals at a density of 51.3 buffalo/km2 (a continental record for the present; Lake Manyara National Park in Tanzania reached nearly twice as much: Prins and Douglas-Hamilton, Reference Prins and Douglas-Hamilton1990). In contrast, the Tsavo population decreased from an estimated 34,600 in 1991 to 5500 in 1997 (East, Reference Dupuy1998) with no strong evidence of recovery so far (~8000 in 2021). Although the Kenyan population shows a cumulative increase of about 40 per cent between 2008 and 2021, recovering the numbers from the early 1990s (approximately 95,000 buffalo) is challenging in a context of increasing competition with humans and cattle for resources (water, space and forage; Waweru et al., Reference Waweru, Omondi and Ngene2021). The effects of the 2022 drought with some heavy buffalo mortality in, for example, Lewa Downs (Susan Brown, personal communication), were not yet known when we finalized this chapter.

Rwanda

The Cape buffalo formerly occurred at high densities in Akagera and Volcanoes NPs. The population of Akagera NP, estimated to number 10,000 in 1990 (East, Reference Dupuy1998), subsequently declined due to the 1994 genocide and political unrest. The park also faced a two-thirds reduction in size to about 1120 km2. Since 2002, buffalo numbers have been increasing again, reaching ~3400 individuals in 2019 (Macpherson, Reference Macpherson2019).

In Volcanoes NP, a dung count undertaken in 2004 suggested a population of ~900 (2.0 ind./km2; Owiunji et al., Reference Owiunji, Nkuutu and Kujirakwinja2005). We are not aware of more recent surveys, but given the excellent protection of Volcanoes NP, as testified by the increasing number of mountain gorillas, we assume that the number of buffalo remained constant. In contrast, the buffalo was reported extinct at Lake Kivu shore and nearby forests (including Gishwati–Mukura) as well as Nyungwe NP (Cockar, Reference Cockar2022).

Somalia

The Cape buffalo formerly occurred in the south of the country in areas with permanent water along the lower Shebelle and lower Juba Rivers (Fagotto, 1980). At the end of the twentieth century, agricultural settlement and hunting pressure eliminated the buffalo from most of its former range, except in the Bushbush NP area (now Lag Badana NP), where it occurred in good numbers (East, Reference Dupuy1998). Buffalo presence was recently reported in Lag Badana National Park and surrounding areas in Jubalan (Gedow et al., Reference Fusari, Lopes Pereira and Dias2017), but the total number was not reported.

South Sudan

Sidney (Reference Sidney1965) reported that large herds of Central African savanna buffalo were commonly found in grassy plains. Although variations in numbers could be found, the subspecies population was very healthy in South Sudan, with probably several tens of thousands of individuals. Small migrations between the rainy and dry seasons were also observed. East (Reference Dupuy1998) also reported large populations of several thousand individuals in the main South Sudan protected areas (Boma NP and Shambe Nature Reserve), but warned that meat hunting pressure was very high. This declining trend appears to remain in process. Fay et al. (Reference Fargeot, Drouet-Hoguet and Le Bel2007) recorded ~10,200 buffalo in the protected areas of Southern Sudan (mainly in Zeraf and Sambe game reserves), while aerial reconnaissance surveys spotted only 285 individuals in 2013 and none in 2016 (Elkan et al., Reference Elkan, Fotso and Hamley2013a, Reference Elkan, Hamley and Mendiguetti2016). From this we infer that the conservation status of the Central African savanna buffalo should be considered under major threat in South Sudan.

Sudan

The Central African savanna buffalo is historically present in the south-eastern tip of Sudan along the border with Ethiopia. Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Mohammed and El Faki2018) reported observations of African buffalo in the Dinder–Alatash transboundary protected area (13,000 km2; Sudan and Ethiopia) during five field trips undertaken between 2015 and 2018.

Tanzania

Although once common throughout the country, the range of the Cape buffalo covered less than half its area of distribution at the end of the last century, with an estimated population of 342,000 individuals (East, Reference Dupuy1998). Tanzania today is still the country with by far the largest number of buffalo, with an estimated population of at least 240,000 individuals. The country has established a dense network of protected areas covering slightly more than 30 per cent of the land surface area (MNRT, 2021) and implementing a range of nature conservation models with both (i) consumptive use of wildlife in Game Reserves, Game Controlled Areas and Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) and (ii) non-consumptive use of wildlife in National Parks and Ngorongoro Conservation Area.

Tanzania is the only country with single populations of buffalo exceeding 50,000 individuals (Figure 4.6). There are three of these strongholds: (i) the Serengeti Ecosystem (~23,700 km2) in the northern part of the country hosts a population of about 69,000 individuals (TAWIRI, 2021a), (ii) the Selous–Mikumi Ecosystem (~74,000 km2) in the south-east of the country has a population of about 66,800 individuals (TAWIRI, 2019a) and (iii) the adjacent Katavi–Rukwa and Ruaha–Rungwa Ecosystems (~83,000 km2) located in the west-centre of the country hold a population of about 53,000 individuals (TAWIRI, 2022).

Nearby the Serengeti Ecosystem, the Tarangire–Manyara Ecosystem (~15,500 km2) also hosts an important buffalo population, estimated at about 19,000 individuals (TAWIRI, 2020). Mkomazi NP (~2800 km2) in the north-east supports about 600 individuals (TAWIRI, 2019b). Saadani NP and Wami Mbiki WMA on the coast host about 1000 individuals (Edward Kohi, personal communication). By contrast, the last census undertaken in West Kilimanjaro–Lake Natron Ecosystem (~10,000 km2) reported a population of 46 buffalo only (TAWIRI, 2021b), a very low number largely due to cattle encroachment (Prins and De Jong, Reference Prins, De Jong, Kiffner, Bond and Lee2022).

In the north-western part of the country, the Malagarasi–Muyovozi Ecosystem hosts an important buffalo population, estimated at about 28,300 individuals (Edward Kohi, personal communication). The recently created Burigi–Chato NP (2200 km2) west of Lake Victoria along the border with Rwanda has a small number of buffalo, as well as Rubondo Island NP in Lake Victoria (Edward Kohi, personal communication). At the northwestern tip of the country, Ibanda Kyerwa NP (200 km2) supports about 215 buffalo (Edward Kohi, personal communication).

Finally, several mountainous and/or densely forested areas host buffalo populations of which the recent numbers are unknown: Arusha NP and Mount Meru Forest Reserve, Kilimanjaro NP and Udzungwa Mountains NP. Therefore, given these knowledge gaps, the estimates provided for Tanzania should be considered as minimum values.

In 2022, the conservation status of buffalo in Tanzania is uneven. On the positive side, (i) not only is Tanzania the only country holding single populations of over 50,000 buffalo, but there are three of these populations in the country; and (ii) several ecosystems show positive trends with growing buffalo populations, for example Serengeti Ecosystem. On a more worrying side, the overall national trend of buffalo is on the decrease due to (i) severe encroachment by livestock tending to replace buffalo in several ecosystems (Prins, Reference Prins1992; Musika et al., Reference Musika, Wakibara, Ndakidemi and Treydte2021, Reference Musika, Wakibara, Ndakidemi and Treydte2022; Prins and De Jong, Reference Prins, De Jong, Kiffner, Bond and Lee2022) and (ii) steady agricultural expansion and associated settlements.

Uganda

The Cape buffalo was formerly widespread in large numbers in savannas, with putative intermediates with the forest buffalo in the southwest (Greater Virunga Landscape) (East, Reference East1998). However, genetic samples so far have not yet recognized these putative hybrids in Uganda (see Chapter 3). It is noteworthy that western Uganda is a zone of introgression between several subspecies where the taxonomy is subject to controversy.

Cape buffalo are now confined to three conservation areas. In Queen Elizabeth NP (2110 km2), the most recent survey reported ~15,800 buffalo (Wanyama et al., Reference Wanyama, Balole and Elkan2014) and the population seemed to be increasing from the ~10,300 reported in 2010 (Plumptre et al., Reference Plumptre, Kujirakwinja and Moyer2010). In Murchison Falls NP and surrounding wildlife reserves (5030 km2), an aerial survey undertaken in 2016 resulted in an estimate of ~15,200 buffalo (Lamprey et al., Reference Lamprey, Ochanda and Brett2020), and the population also seemed to be increasing (from ~9200 in 2010 (Rwetsiba and Nuwamanya, Reference Rwetsiba and Nuwamanya2010). Finally, in Kidepo NP and Karenga Community Wildlife area (2400 km2), the last survey reported ~7500 individuals, mainly located inside the park (~6600; Wanyama et al., Reference Wanyama, Kisame and Owor2019). The trend is also up in Kidepo NP (from ~3800 in 2008 to ~6600 in 2019; WCS Flight Programme, 2008). These three conservation areas (together ~9400 km2) host a population of about 38,500 buffalo (4 buffalo/km2). Smaller populations were also recently reported in Lake Mburo Conservation Area (1290 km2 with ~1500 buffalo; Kisame et al., Reference Kisame, Wanyama, Buhanga and Rwetsiba2018a) and Pian Upe Wildlife Reserve (no estimate; Kisame et al., Reference Kisame, Wanyama, Buhanga and Rwetsiba2018b). Hence, the total number of Cape buffalo in Uganda is now about 40,000 head, which compares very favourably to the estimate of about 22,000 a few decades ago (East, Reference Dupuy1998).

The presence of forest buffalo was recently confirmed in Semuliki NP in 2020 (Naomi Matthews and Stuart Nixon, personal communication). No forest buffalo presence was reported from Mgahinga Gorilla NP since 2003 (Hickey et al., Reference Hauptfleisch and Brown2019) or from Kibale NP from 2013 to 2021 (Rafael Reyna-Hurtado and Jean-Pierre d’Huart, personal communication). In the latter park, records of buffalo inside the forest are related to savanna buffalo coming from Queen Elizabeth NP through the Dura corridor.

Southern Africa

Angola

Apart from the arid coastal strip in the southwest, African buffalo formerly occurred very widely, with the Cape buffalo in the south and intermediate forms with the forest buffalo in the north (East, Reference Dupuy1998). During the civil war (1975–2002), thousands of buffalo were slaughtered by the Angolan army for food. Since the 2000s, buffalo populations have remained low due to widespread poaching, habitat degradation, human encroachment and the presence of land mines. However, very little information is available on the status of buffalo in this country, especially in the central plateau and the northern and eastern regions.

Cape buffalo are still relatively common in the south-eastern parts of Angola, especially in the Mucusso region and in Mavinga and Luengue-Luiana NPs (Funston et al., Reference Fraticelli, Ourde and Arnulphy2017; Beja et al., Reference Beja, Pinto, Veríssimo, Huntley, Russo, Lages and Ferrand2019; Petracca et al., Reference Petracca, Funston and Henschel2020), but their actual numbers have not been assessed. Naidoo et al. (Reference Naidoo, Preez, Stuart-Hill and Beytell2014) report frequent movements of Cape buffalo between Angola and Namibia, particularly along the northern banks of the Okavango River, and west of the Cuando River. Large herds (over 1000 animals) were also reported to aggregate in the southeast of Luiengi–Luiana NP along the Kwando River just before the rainy season (Roland Goetz, personal communication).

In the northern Quiçama region, there were an estimated 8000 so-called ‘forest buffalo’ prior to the civil war of 1975–2002 (Braga-Pereira et al., Reference Braga-Pereira, Peres and Campos-Silva2020). During the war, uncontrolled poaching severely reduced the populations, which are now confined to a few small herds in Quiçama NP (Groom et al., Reference Gonfa, Gadisa and Habitamu2018), Luando Natural Integral Reserve (Elizalde et al., Reference Eban2019) and Cangandala NP (David Elizalde, personal communication). Although surprising at this latitude, recent photographs of buffalo taken by camera traps in Quiçama NP and Luando Natural Integral Reserve confirm the presence of buffalo that phenotypically correspond to the forest buffalo (David Elizalde, personal communication). Outside protected areas, recent sightings of buffalo were reported in the north-western section of the country, in the region of Mussera (Zaire Province), Quissafo-Ndalatando and Cassoxi (Cuanza Norte Province), and in the Pingano Mountains (Uige Province) (David Elizalde, personal communication).

Botswana

Cape buffalo are found only north of 20° S in the Okavango–Chobe region and wildlife movements are constrained by veterinary fences erected to control the spread of livestock diseases. In a 2018 aerial total count covering northern Botswana (~103,700 km2, including Moremi Game Reserve, Chobe NP, Makgadikgadi Nxai Pan NP and surrounding WMAs), the buffalo population was estimated to be some 28,500 individuals (Chase et al., Reference Chase2018). For the record, a similar survey undertaken in 2010 reported an estimate of 39,600 individuals (Chase, Reference Chardonnet, Fusari and Dias2011), while East (Reference Dupuy1998) reported about 27,000 head. It thus appears that the population is fairly constant.

Eswatini (Swaziland)

Cape buffalo were reintroduced in Swaziland, where the indigenous population was extirpated (Tambling et al., Reference Tambling, Venter, Toit, Child, Child, Roxburgh, Do Linh San, Raimondo and Davies-Mostert2016). They now occur in the Mkhaya Private Game Reserve (~20 animals, 0.2 ind./km2; Tal Fineberg, personal communication, 2021).

Lesotho

Buffalo was extirpated from this country (Tambling et al., Reference Tambling, Venter, Toit, Child, Child, Roxburgh, Do Linh San, Raimondo and Davies-Mostert2016), but historically it had occurred here even though it was no longer present a few decades ago (East, Reference Dupuy1998).

Malawi

In the late 1990s, the Cape buffalo was confined to protected areas such as Lengwe, Kasungu and Nyika NPs as well as Nkhotakota and Vwaza Marsh Game Reserves. Their population was estimated at about 1850 individuals (East, Reference Dupuy1998).

To our knowledge, buffalo occur today in Majete and Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserves as well as Liwonde and Kasungu NPs. In Majete Wildlife Reserve, where 306 buffalo were reintroduced between 2006 and 2010, the buffalo population was estimated at ~1800 individuals in 2020 (Sievert and Adenorff, Reference Sievert and Adenorff2020). Between 2016 and 2017, over 100 buffalo were moved from Majete Wildlife Reserve and Liwonde NP to Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve as part of a rehabilitation programme undertaken by African Parks. Similarly, 80 buffalo were translocated from Liwonde to Kasungu NP in 2022 as part of a restoration programme (African Parks, personal communication).

Mozambique

Cape buffalo populations occurred throughout the country until the 1970s, but suffered greatly from 25 years of war (independence war 1964–1974 then civil war 1977–1992) (East, Reference Dupuy1998). Buffalo are well present in the northern part of the country (Niassa and Cabo Delgado Provinces). In Niassa Special Reserve, they were successively estimated at 6800 (2009), 6200 (2011) and 7100 (2014) individuals (Craig, Reference Craig2011a; Grossmann et al., Reference Grossmann, Lopes Pereira and Chambal2014a), with a density surprisingly more than five times lower than in the neighbouring Selous complex in Tanzania. In Quirimbas NP and adjacent areas, aerial sample counts undertaken in 2011 and 2014, respectively, reported 0 and 88 buffalo observations with no population estimate (Craig, Reference Craig2011b; Grossmann et al., Reference Grossmann, Lopes Pereira and Chambal2014b). We did not obtain figures for the buffalo occurring in the Chipanje Chetu community-based natural resource management initiative (6500 km²) north-west of Niassa Special Reserve, and for the numerous hunting blocks outside the reserve in the two northern provinces.

Further south, in Zambezia Province, Gilé National Reserve embarked on a restoration programme by reintroducing extinct large mammal species such as buffalo: 67 buffalo were reintroduced in 2012 and 2013–2020 from the Marromeu complex (the National Reserve and numerous trophy hunting areas) and Gorongosa NP, then 47 buffalo from the trophy hunting areas within the Niassa Special Reserve (Chardonnet et al., Reference Chardonnet, Fusari and Dias2017; Fusari et al., Reference Fusari, Lopes Pereira and Dias2017). The population in the now Gilé NP was estimated at about 139 individuals in 2017 (Macandza et al., Reference Macandza, Bento and Roberto2017). Mahimba Game Reserve, north bank of Zambezi River, would also host around 850 individuals (Grant Taylor, personal communication). In Tete Province, an aerial survey conducted in 2014 south and north of Lake Cahora Bassa and Magoe NP including the Tchuma Tchato community programme reported 4300 buffalo (Grossmann et al., Reference Grossmann, Lopes Pereira and Chambal2014c).

The largest African buffalo population of Mozambique is located south (right bank) of Zambezi River (Manica and Sofala Provinces). At the mouth of the Zambezi River into the Indian ocean (the famous Zambezi delta), the open floodplains of the Marromeu Game Reserve and surrounding trophy hunting areas (‘Coutadas’) host about 21,300 individuals according to the latest aerial total count (Macandza et al., Reference Macandza, Ntumi and Mamugy2020). Gorongosa NP was restocked between 2006 and 2011 with 186 buffalo from Kruger and Limpopo NPs (Carlos L. Pereira, personal communication). An aerial total count conducted in 2020 reported 1200 buffalo (Stalmans and Peel, Reference Stalmans and Peel2020). Finally, the trophy hunting areas located northwest of Gorongosa NP likely hold about 1000 buffalo (Willie Prinsloo, Joao Simoes Almeida and Grant Taylor, personal communication).

The Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area lies in South-Central and Southern Mozambique. In its northern section (Inhambane Province), a restoration programme has been underway since 2017 in Zinave NP, where the buffalo was extinct, with the reintroduction of 250 buffalo from Marromeu Reserve and surrounding trophy hunting areas (Mike La Grange, personal communication). A 2021 Zinave census reported 479 buffalo in the core sanctuary area (Antony Alexander, personal communication). Further south (Gaza Provinces), Banhine NP is estimated to host about 200 buffalo (Joao Simoes Almeida, personal communication). The Chicualacuala trophy hunting areas, located along Gonarezhou NP (Zimbabwe) also contain around 800 buffalo, but this figure is variable because the population undertakes seasonal migrations through Gonarezhou NP (Anthony Marx and Joao Simoes Almeida, personal communication). Finally, two areas adjacent to Kruger NP (South Africa) also host significant buffalo populations. The first is the Limpopo NP, with a population estimated around 5000 based on the 2018 census (Antony Alexander, personal communication). The second is the Great Lebombo Conservancy (including Sabie Game Park) with around 2000 buffalo (Joao Simoes Almeida, personal communication).

In the south-eastern tip of the country (Maputo Province), around 250 buffalo have been reintroduced in the Maputo Special Reserve since 2016 and their population is estimated at 300 (Antony Alexander, personal communication). Finally, around 50 individuals are present in Namaacha Catuane Community Area (close to the borders with Eswatini and South Africa; Joao Simoes Almeida, personal communication).

Buffalo are also present in numerous fazendas do bravio (private game ranches) and Coutadas (State-owned protected areas leased and managed by the private sector for hunting tourism). Most of these areas are unfenced, so nearly all buffalo in Mozambique are wild and free-ranging.

Overall, the buffalo has been experiencing a spectacular post-civil-war recovery in Mozambique since 1992, mainly by reintroductions where the species had become extinct, and by reinforcements of rump populations. In recent years, buffalo translocations have been conducted frequently in Mozambique. Some of the buffalo originate from South Africa, but most are indigenous, coming from trophy hunting areas within the Marromeu complex and the Niassa Special Reserve.

Namibia

Because the availability of perennial water is a key requirement for African buffalo, much of Namibia is not suitable for naturally occurring populations of Cape buffalo, except for the Caprivi Strip in the south and the area along the border with Angola in the north. As with probably all African buffalo populations, those in Namibia were drastically reduced during the 1890s rinderpest epidemic. Small herds survived along the perennial rivers of the far north-eastern Kavango East and Zambezi regions (Martin, Reference Martin2002). By 1934, their distribution had spread somewhat west and southwards to include what is now known as Kavango West, and small seasonal populations in Ohangwena, Omusati and Oshikoto regions (Shortridge, Reference Shortridge1934). Any further natural expansion was halted by the erection of a veterinary control fence in the 1960s to protect commercial cattle ranching from the central north southwards. The only exception to the present day has been the reintroduction of two isolated herds in the Waterberg Plateau Park and the Nyae-Nyae communal conservancy. In Waterberg, the founder population of 48 individuals were sourced gradually between 1981 and 1991 from the disease-free Addo Elephant NP population in South Africa at a rate of approximately four a year, while four animals were added to Waterberg from a zoo in then Czechoslovakia in 1986, and 11 from Willem Prinsloo Game Reserve in South Africa, also in 1986 (Martin, Reference Martin2008). The location of the herd on the plateau bordered by sandstone cliffs does not allow the buffalo to move from the plateau. In Nyae-Nyae, 30 individuals from a natural population in the area were fenced off in 1996. Only one individual tested positive for FMD, and was destroyed (Martin, Reference Martin2008). The Waterberg population has grown to at least 800 individuals, and the Nyae-Nyae population to about 250 head, both considered disease-free (Kenneth Uiseb, personal communication). The Zambezi and Kavango populations move freely into and from Angola and Botswana within the Kavango–Zambezi (KAZA) transboundary conservation area (Naidoo et al., Reference Naidoo, Preez, Stuart-Hill and Beytell2014). The current estimate in Namibia’s portion of KAZA is 7500 individuals based on a 2019 aerial census (Craig and Gibson, Reference Craig and Gibson2019). This represents a steady increase from 4500 in 2014 and 5500 in 2015 (Craig and Gibson, Reference Craig and Gibson2014, Reference Craig and Gibson2015).

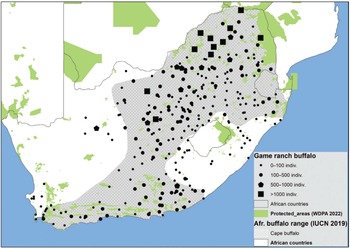

South Africa

Cape buffalo were historically present throughout the country except for the arid western section. Free-ranging Cape buffalo were extirpated from their former range and are now totally confined within fenced areas (except Kruger NP along the Zimbabwe and Mozambique borders). At the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, the total number of buffalo in the country was about 50,000 head (East, Reference Dupuy1998). Based on the data collected, the present buffalo population stands at an estimated 121,000 heads, distributed between national parks (~40,000; 28 per cent), game parks (~26,000; 10 per cent) and privately owned game farms (~75,000; 62 per cent) (Chapter 14; Cornélis et al., Reference Cornélis, Melletti, Renaud, Fonteyn, Bonhotal, Prins, Chardonnet and Caron2023).