Book contents

- Flodoard of Rheims and the Writing of History in the Tenth Century

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought

- Flodoard of Rheims and the Writing of History in the Tenth Century

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Flodoard, His Archbishops and the Struggle for Rheims

- Chapter 2 Narrative and History in the Annals

- Chapter 3 Institutional History and Ecclesiastical Property

- Chapter 4 History, Poetry and Intellectual Life

- Chapter 5 Flodoard’s Age of Miracles

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

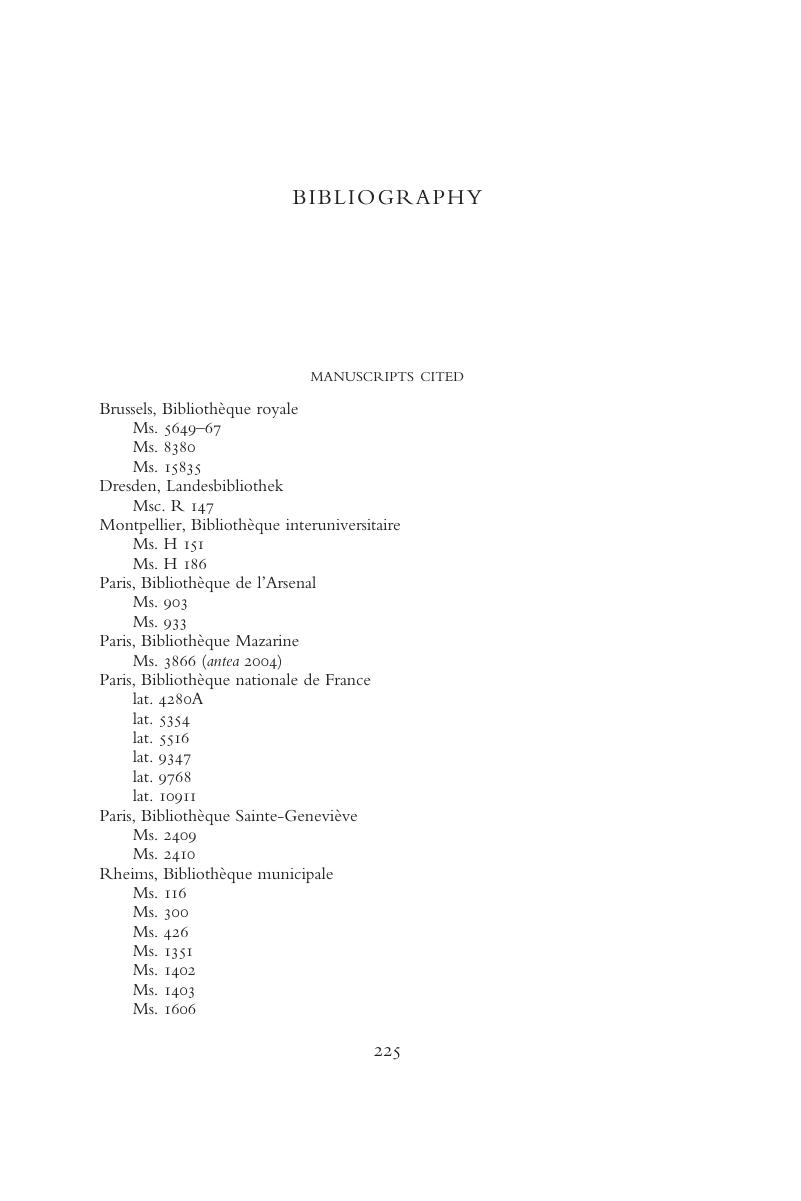

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2019

- Flodoard of Rheims and the Writing of History in the Tenth Century

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought

- Flodoard of Rheims and the Writing of History in the Tenth Century

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Flodoard, His Archbishops and the Struggle for Rheims

- Chapter 2 Narrative and History in the Annals

- Chapter 3 Institutional History and Ecclesiastical Property

- Chapter 4 History, Poetry and Intellectual Life

- Chapter 5 Flodoard’s Age of Miracles

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019