This chapter investigates the various ways in which operettas were changed as they transferred from one social-cultural context to another. The term ‘adaptation’ generally refers to remediation – a reworking from one medium to another – but the cultural transfer of operettas more commonly involved the creation of new versions of works already designed for the stage (the adaptation of stage operettas as films is discussed in Chapter 3). This is not to deny that differences could be considerable, but, most of the time, changes were made to accommodate differing cultural experiences and expectations, which is why the term ‘transcreation’ is useful. It was never a case of merely translating the German book and lyrics; it was necessary to capture the cultural meanings and emotional nuances that resist direct translation, enabling them to be recognized in a new context.

Developed as a concept in advertising in the 1970s, transcreation has become associated with the creative transformation of images and modification of storylines in computer and video games as part of a strategy to reach different cultural markets.Footnote 1 In the cultural transfer of operetta, transcreation encompassed scene and costume design as well as interpolated numbers, character modifications, and structural changes. None of this is aptly described as translation, yet to use the word ‘transformation’ would be to go too far. The different versions of stage works often remain fundamentally the same.

Linda Hutcheon has stressed that cultural and social meaning cannot be conveyed effectively by merely translating words.Footnote 2 This, too, can be linked to the idea of transcreation. In some cases, what is at stake is translation in the sense in which Nicolas Bourriaud has called for creative artists to translate the meaning of a cultural artifact for an ‘outsider’. For Bourriaud, translation is at the heart of an important ethical and aesthetic struggle, that of ‘rejecting any source code that would seek to assign a single origin to works and texts’.Footnote 3 Arguments advanced in poststructuralism and deconstruction have made it difficult to claim authority for an ‘original’: the original, itself, exists in an intertextual web. Fidelity discourse has been abandoned by adaptation theorists, although comparison of similarities and differences remains of interest.Footnote 4

The ease with which cross-cultural translation could be achieved illustrates the commonalities of twentieth-century metropolitan experience, and the practices of translation and transcreation are significant for operetta’s character as a cosmopolitan genre. Popular forms of entertainment often carry more conspicuous traces of the cultural context in which they were created than do high-status art forms. Artistic respect for opera ensured that it was seldom reworked to fit a changed cultural environment to the same extent as operetta. Opera had often been subject to adaptations in its earlier days, but that diminished after the polarization of ideas of art and entertainment from the middle of the nineteenth century on, when adaptation came to be seen as demeaning. Even in the most provocative Regietheater, alterations to an opera’s libretto are rare, and revisions to its music even rarer. Moreover, operas are almost always given in the original language. Operettas, on the other hand, are subjected to changes in language, structure, and scene, and often have added music. Reginald Arkell, who, with A. P. Herbert, was responsible for the book and lyrics of the West End production of Paganini in 1937, was taken aback when its composer, Lehár, and its lead singer, Richard Tauber, opposed them strongly. Theatre publicist MacQueen-Pope shared Arkell’s consternation:

in those days, when the rights of a continental success were secured for London, little attention was paid to any clauses in the contract calling for purity of performance and strict adherence to the story, and requiring that no numbers should be interpolated.Footnote 5

The creation of new versions offered opportunities for originality. Such a task did not have to be tied to ideas of fidelity and respect for the former text; it could be a reimagining or a reinterpretation.

It is not uncommon to find that the libretto of an operetta is already an adaptation of a novel, poem, or stage play. The Merry Widow, for example, was an English version of Die lustige Witwe, which was already a musical adaptation of Henri Meilhac’s play L’Attaché d’ambassade, performed at the Théâtre du Vaudeville, Paris, in 1861.Footnote 6 When Ben Travers, now best known as the author of the Aldwych farce Rookery Nook (1926), authored the book and lyrics of The Three Graces for the Empire Theatre in 1924, he reworked Lehár’s Der Libellentanz (1923), which was already a reworking by Alfred Maria Willner of Carlo Lombardi’s new libretto to Lehár’s Der Sternglucker (1916), given in Milan as La danza delle libellule (1922). Other works that were much revised, if not to similar extent, were Lehár’s Endlich Allein (becoming Schön ist die Welt) and Der gelbe Jacke (becoming Das Land des Lächelns), Kálmán’s Der gute Kamerad (becoming Gold gab ich für Eisen), and Fall’s Der Rebell (becoming Der liebe Augustin). It is better, perhaps, to speak of prior versions than original versions, to relinquish searching for an original, and accept that different versions exist, each of which may contain something of unique artistic value. When Eduard Künneke visited his birthplace, Emmerich am Rhein, in later life, he signed the town guest book and appended a musical quotation, the beginning of ‘Ich bin nur ein armer Wandergesell’ from Der Vetter aus Dingsda. However, Künneke also added the title and song lyrics from its London production (The Cousin from Nowhere, ‘I’m Only a Strolling Vagabond’).Footnote 7 It would appear he identified with both versions.

The remapping of a scene onto a locally known place that would conjure up similar associations to those that were culturally familiar to the former audience was part of transcreation. It was an important means of reproducing similar pleasure and understanding. The fact that such substitutions were easily made points to a certain equivalence in the experience of urban environments. In The Girl on the Film, James T. Tanner’s West End version of Filmzauber, Adrian Ross’s lyrics have Freddy and Max singing about walking down Bond Street, rather than Unter den Linden. The transcreation of Filmzauber also had to deal with differing sociocultural nuances. The German version featured the character Euphemia Breitsprecher, whom Tobias Becker argues would have been immediately recognized in Berlin as a caricature of the social reformer who believed films posed moral danger and should be restricted to serving educational purposes.Footnote 8 Tanner exchanges her for a film enthusiast and former actor, Euphemia Knox. It is an indication that the new medium of film met with less moral concern in London than it did in Berlin. If anxiety was felt in the UK, it was about the prospect of American films destabilizing the British social hierarchy with their democratic values.Footnote 9 The notion of the sinful metropolis was stressed in Berlin through the character Käsebier. His counterpart in London, Clutterbuck, is more concerned about foreign threats, especially invasion. Given that the date of Tanner’s version was 1913, the London audience would have linked such threats to Germany. Ostensibly, it concerns Napoleon, so the audience may have felt reassured that, since the once-feared invasion of England by Napoleon failed to materialize, a German invasion was equally unlikely. Both versions included the projection of a film in the final act. The Gaiety was obliged to obtain a cinema licence in order to do so.Footnote 10

The Broadway version of The Girl on the Film was almost identical to the West End version but became the subject of a historic plagiarism case in 1914, when an American court declared that another theatrical production, All Aboard, breached its copyright by depicting a French invasion in a similar manner. That offers a neat illustration of the distinction between legitimate reworking, following the formal acquisition of rights, and plagiarizing for an unrelated production.

There was one location, a country of mountains, brigands, and tyrants, that had many names but remained essentially the same. First introduced as Ruritania in Anthony Hope’s novel The Prisoner of Zenda (1894), it was a fictitious version of the Balkans that became better known by Western European and American audiences than the Balkans themselves. Ruritanian locations featured in many operettas from German, British, and American stages. The homeland of the merry widow was Pontevedro in the Balkans (a thinly disguised Montenegro, which had defaulted on a large debt to Austria at the end of the nineteenth century). It became Marsova in the English version of the operetta, Farsovia in the burlesque at Weber’s music hall, Monteblanco in the MGM silent film of 1925, and Marshova in MGM’s later film of 1934. Such place names served to conjure up romantic adventures in the wilder parts of Europe: Hugo Hirsch’s Toni has a plot involving the loss of a precious jewel from Mettopolachia, and the leading characters of Jean Gilbert’s Katja, the Dancer are ex-aristocrats of Koruja.

Sometimes a new version departed radically from its German stage version, but the fact that such adaptations usually affected only the scenes and dialogue indicates the lack of any sense of perplexity about musical style. The existing music may have been sometimes chopped about and re-orchestrated, but melody, harmony, and rhythm were seldom altered, although additional numbers were often interpolated. Basil Hood may have claimed that he made almost a new play out of The Count of Luxembourg,Footnote 11 but the music was still that of Lehár. Musical style in an operetta often appears to be independent of the setting. The mixture of styles in Künneke’s Der Vetter aus Dingsda, which included transcultural modern styles such as the valse boston, tango, and fox trot, hardly seems designed to indicate a location in the Netherlands. Indeed, the New York version shifted continents for an American Civil War setting.

Few would argue that a musically unsatisfying opera or operetta has survived in the repertoire owing to a first-rate libretto. Yet it is not uncommon to hear of stage works surviving because of the quality of the music alone. A typical comment is found in a review of Caroline, the Broadway version of Der Vetter aus Dingsda: ‘Last night’s audience … seemed not much disturbed by the poorness of the book, and it is safe to assume that future audiences will also refuse to be bothered by it.’Footnote 12 Nevertheless, it had a short run, and most Anglophone revivals of this work have been of its London incarnation as The Cousin from Nowhere. It should also be emphasized that the German libretto was skilfully constructed (after Max Kempner-Hochstädt’s comedy) by Herman Haller, with lyrics by Rideamus (Fritz Oliven).Footnote 13

On those uncommon occasions when a libretto was given fresh music, we may assume that the libretto was thought better than the existing music. Rida Johnson Young based her libretto for Maytime (1917) on the libretto of Wie einst im Mai (1913) by Rudolf Bernauer, Rudolf Schanzer, and Willy Bredschneider. It was a biographical storyline contrasting past and present, like Coward’s Bitter Sweet a decade later. It previously had music by Walter Kollo, which was replaced with music by Sigmund Romberg. A similar thing happened with Madame Sherry, which had music by Hugo Felix in London and Karl Hoschna on Broadway. Other examples are Robert B. Smith’s adaptation of Felix Dörmann’s Follow Me (music by Romberg, but originally by Leo Ascher) and Harry B. Smith’s adaptation of Leopold Kremm and Carl Lindau’s The Strollers (music by Ludwig Englander, but originally by Carl Ziehrer). One of the most successful musical comedies at the Gaiety Theatre in London was based on James Tanner’s adaptation of the libretto by Julius Freund and Wilhelm Mannstaedt for Julius Einödshofer’s Ein tolle Nacht (Berlin, 1895). It was retitled The Circus Girl and ran during 1896–98 with music by Ivan Caryll and Lionel Monckton. There is no doubt that the right libretto can help an operetta succeed. David Ewen blames the failure in 1871 of Johann Strauss’s Indigo und die vierzig Räuber on Maximilian Steiner ‘whose text had been so confused that it was impossible to follow the story line’.Footnote 14 With a new libretto by Leo Stein and Carl Lindau, and with music arranged by Ernst Reiterer, it re-emerged in 1906 as Tausendundeine Nacht and achieved prolonged success.

Sometimes it was necessary to ‘tone down’ an operetta for British and American audiences. Fall’s Die geschiedene Frau (1908) became The Girl in the Train (1910) to avoid a title that made uncomfortable mention of divorce (in liberal Paris the title was unhesitatingly given as La Divorcée). The Times reviewer imagines that there was ‘some difficulty in reducing the flavour of [the] original to the standard of respectability required in the Strand’.Footnote 15 The New York Times reviewer informs the reader: ‘Reports from Germany tell us that “Die Geschiedene Frau” – literally “The Divorced Wife” – was very, very naughty indeed in its original version.’ The writer then adds: ‘The courtroom scene, even in English, is a bit daring.’Footnote 16 That may be due to the input of its American adapter Harry B. Smith. The British were more prone to be embarrassed than Americans, an example being the twinge of unease in the Times review of Fall’s Madame Pompadour, as it informs the reader coyly that the eponymous character was ‘a distinctly naughty young lady’.Footnote 17

Transcreation included structural changes to cater to local theatrical taste, for instance, a preference for two acts rather than three. Adrian Ross reduced Die geschiedene Frau from three acts to two for The Girl in the Train, but Harry B. Smith retained the three-act structure for Broadway. Another reason for structural change was the desire to create parts for popular performers. Connie Ediss was introduced into the West End cast to play a comic role, which differed from the confidential maid in the German version. This had knock-on effects. Rutland Barrington, who played the President of the Divorce Court, recalls, ‘with the inclusion in the cast of Miss Connie Ediss it became imperative to provide her with a song, sua generis, and an additional author was at once called in to furnish it, with the happy result of a great success for Miss Ediss in a ditty entitled “When I was in the Chorus at the Gaiety”’.Footnote 18 It was an unlikely previous career for a maid-servant of a Dutch family in Amsterdam. Barrington says it was much liked by the audience but damaged the drama: ‘A sympathetic little scene between the mistress and maid was eliminated entirely, to the disadvantage of the plot, and those of us who had to deal with the story were distinctly conscious of an effort being required to reunite the broken thread.’Footnote 19 Barrington confessed that he, himself, was probably engaged because he was well-known for performing in Gilbert and Sullivan, and this operetta bore some resemblance to Trial by Jury.Footnote 20 He, too, was to have an interpolated number, ‘Memories’, the lyrics of which he had written to a tune Fall composed just before leaving London.Footnote 21

There were certain conventions that audiences expected, such as a subplot with a comic pairing of buffo and soubrette characters who contrasted with the leading couple. Yet that was replaced with a romantic subplot in The Merry Widow and was done away with altogether in The Last Waltz.Footnote 22 Straus’s The Last Waltz also omits the comedian, although this was quickly ‘corrected’ in the Broadway version, by the inclusion of comedians on roller skates. It was also given jazzy musical interpolations. When Robert Evett and Reginald Arkell saw it at the Century Theatre, that proved a decisive factor in persuading them to make a different version for London.Footnote 23

Try-outs were helpful to the honing of adaptations before operettas transferred to Broadway or the West End. The Manchester try-out of The Last Waltz revealed dramatic weakness in the third act. It was resolved before the try-out ended and in time for the London premiere.Footnote 24 The Dollar Princess was revised for Daly’s after a try-out at the Prince’s Theatre, Manchester, in December 1908, in which Alice was Conder’s daughter, as in the German version. In London, Alice became Conder’s sister, and extra musical numbers by Richard and Leo Fall were added. The script in the Lord Chamberlain’s Plays (LCP) collection at the British Library is the one used in Manchester. Although the LCP scripts do not show later revisions, they are a unique resource for studying English versions of the operettas, because most published librettos were actually of lyrics only, omitting dialogue and action. In addition, there are some copies held in the archive of Weinberger in London. There is no sure location for finding the English versions used on Broadway that differ from those performed in London (see Appendix 6, Research Resources).

From Veuve Madeleine to Witwe Hanna to Widow Sonia

In Meilhac’s comedy L’Attaché d’ambassade, the embassy’s attaché is Count Prax, who becomes Danilo, its secretary, in Die lustige Witwe. The widow is Madeleine Palmer, and it is she, with the new name Hanna, that becomes the focus of the operetta, rather than Danilo – hence, the change of title. The homeland threatened with financial ruin is Birkenfeld, the name of a small Principality that was, at the time of the play’s first performance in 1861, part of the widely dispersed Grand Duchy of Oldenburg. The plot revolves around the difficulty faced by the wealthy Madeleine in finding another husband. Prax tells her that the banker’s fortune she has inherited creates a constant suspicion in her mind, and whenever a man tells her he loves her, it whispers in her ear, ‘it’s not you he loves, but the banker’s fortune’.Footnote 25 Madeleine and Prax did not love one another in the past, as in the operetta. In the play, Prax accompanies Madeleine at the piano while she sings a Spanish song, rather than a homeland song. They perform no waltz with silent lips, because dancing would cause the drama to lose pace. Musical adaptations of spoken plays require reductions to the text in order to compensate for the time taken by music.

The first act is in the home of the Birkenfeld ambassador, the second in Madeleine Palmer’s home, and the third in the home of the Baron and Baroness Scarpa. All are located in Paris. There is no scene in Maxim’s restaurant, which did not exist when the play was written. Instead, the widow holds a fête in order to gauge Danilo’s reactions. When Victor Léon and Leo Stein revised the play they first renamed Birkenfield as Montenegro, and Montenegrin costumes were still used when they changed it to Pontevedro.Footnote 26 This created a political stir: Montenegrin students demonstrated outside the Parliament building in Vienna.Footnote 27 Montenegrins protested in Istanbul, and Serbians and Croatians rioted in Trieste.Footnote 28 Relations were tense between Austria and Serbia; they became even more so in 1909, and this would bring tragic consequences a few years later, following the opportunistic assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.

In The Merry Widow, the dignified Ambassador, Baron Zeta, became the comic figure Baron Popoff played by George Graves, who was at one with Basil Hood’s remodelling of the character, commenting: ‘Of course in Vienna they do not allow their comics so much rope, and he had to take the British mentality into account.’Footnote 29 The name change from Zeta to Popoff was made for humorous effect – sounding both Slavic and like the English slang phrase ‘pop off’ (disappear quickly). Hood created another comic role, Nisch, for W. H. Berry. Lehár composed the music to an interpolated number for him, ‘Quite Parisien’. It contradicts the sentiments of another song, ‘A Balkan State’, which features in the LCP copy.Footnote 30 In this, Nisch, far from loving Paris, declares:

Alas, this inventive rhyming was lost to the public when the number was cut.

George Edwardes commissioned Edward Morton to adapt Die lustige Witwe, but decided Morton had made a confused job of it. So he persuaded Hood to produce rapidly another English version (the lyrics were the responsibility of Adrian Ross). It was only on the opening night that Morton realized his libretto had been replaced. Edwardes was obliged to pay royalties to both authors in order to deter a law suit. The basic plot remained the same, with various name changes: for example, Hanna became Sonia, and Pontevedro became Marsova. The LCP copy shows that Act 3 was written in a hurry: dialogue is occasionally altered, or added, in pencil, and there is a note to say that some comments from Danilo need to be moved to later in the scene. It was Graves, not Hood, who decided to bolster the role of Popoff with additional comic material, a practice for which he was well known. Indeed, some half-dozen years before his appearance in The Merry Widow, he had been obliged to sign a contract prohibiting him from introducing ‘gags’ into his performance.Footnote 31

In Graves’s opinion, Hood had provided insufficient material for the comic role of Popoff and something had to be done about it. He began to make jokes about having a pet hen called Hetty, and they soon developed into humorous anecdotes about his hen’s strange habit of laying bent eggs, and how, after eating brass filings, she laid a door knob. This fictional character gained fame of her own. Graves confessed that his ‘nightly bulletins became so lengthy that the stage-manager used to blow a whistle at half-time’.Footnote 32 He was aware that some adapters and authors disliked interpolated gags, but he insisted that the majority of them realized that ‘the successful musical show is more than merely a book, lyrics, music, and acting’.Footnote 33 He was conscious of making his own contribution to the art world of musical-theatrical entertainment: ‘It is a composite job of work in which the co-operation of the whole team and a liberal spirit of give-and-take all round under the leadership of a single competent director give the best results.’Footnote 34

The differences between this operetta’s productions in London and Vienna were several. The West End widow was younger, and the male lead was a comedian rather than a romantic tenor. Moreover, as the Times critic observed: ‘Miss Elsie is not lustige; she could not be. Gentle, appealing, charming, a little strange and remote, she is everything delightful – except “merry”.’Footnote 35 That was the only marked contrast with the New York production at the New Amsterdam Theatre, which otherwise followed the version at Daly’s. On Broadway, Ethel Jackson was not the ‘demure widow’ of Lily Elsie, wrote the critic for the New York Times; she understood ‘the verve and joy of the part, as well as its seductiveness’.Footnote 36

Lyric Writing

Those writing lyrics for English-language versions of German operetta were generally keen to offer appropriate translations, except when a number’s purpose and character had been altered (as in the opening chorus of the London version of The Dollar Princess). A skilful lyricist would often try to retain the tone of the German text while translating loosely into idiomatic English. An example is Reginald Arkell’s translation of the song ‘Der letzte Walzer’ from Straus’s operetta of that title, for which Julius Brammer and Alfred Grünwald provided the book and lyrics. First, I am quoting it alongside a literal translation.

| Das ist der letzte Walzer, | This is the last waltz, |

| Der lockend dir erklingt, | That allures you with its sound, |

| Der letzte süße Walzer, | The last, sweet waltz, |

| Den dir das Leben singt. | That sings to you of life. |

| Du lieber, letzte Walzer, | You dear, last waltz, |

| O locke nicht so sehr, | Oh, do not entice me so much, |

| O mach’ mir – letzte Walzer – | Oh, make for me – last waltz – |

| Den Abschied nicht zu schwer! | The farewell not too hard! |

Here, for comparison, are Arkell’s lyrics.

Note that it has poetic metre and does not seem as if it was designed for existing music.

Particular problems sometimes arise for the lyricist. Puns, for example, are almost impossible to translate.Footnote 37 Alfred Willner and Fritz Grünbaum’s original lyrics for the refrain of the quartet in Die Dollarprinzessin describe dollar princesses as ‘die kühnsten Schönen der Welt!’ Adrian Ross, in the London version, translates this as ‘The proudest beauties on earth!’ Although ‘die kühnsten Schönen’ does mean ‘boldest beauties’ it can also suggest ‘enterprising beauties’, and, at the same time, is a pun on ‘die schönen Künste’, meaning the fine arts. Ross must have been aware of these nuances, having developed his German language skills while a lecturer at King’s College, Cambridge, in order to enrich his lectures on Frederick the Great.Footnote 38 It should be added, that no attempt was made to deal with these nuances, either, in George Grossmith’s version for Broadway (which, at times, seems to lean heavily on Ross’s work).

Although there were difficulties in finding apt translations for German puns, there was no problem in adding word-play in English, as Ross shows in his lyrics to Franzi and Lothar’s duet ‘Piccolo! Picolo!’ in A Waltz Dream:

Lothar: A Violin who’d lost her beau, She met a princely Piccolo!

Franzi: His tone was so extremely high, She gave a pizzicato sigh!

Lothar: Said he, ‘My darling, share my throne, If I desert you I’ll be blown!’

Franzi: The Violin said, ‘No such thing! I’d only be your second string!’

It is designed to add humour, and goes much further than anything in the German lyrics by Felix Dörmann and Leopold Jacobson:

Lothar: Lehn’ deine Wang’ an meine Wang’

Franzi: bei Flöten und bei Geigenklang!

Lothar: Ich blas’ die Lieb’ prestissimo!

Franzi: Ich geige sie adagio!

Lothar: Wem niemals ein Duett gelang, der bleibt ein Narr sein Leben lang.

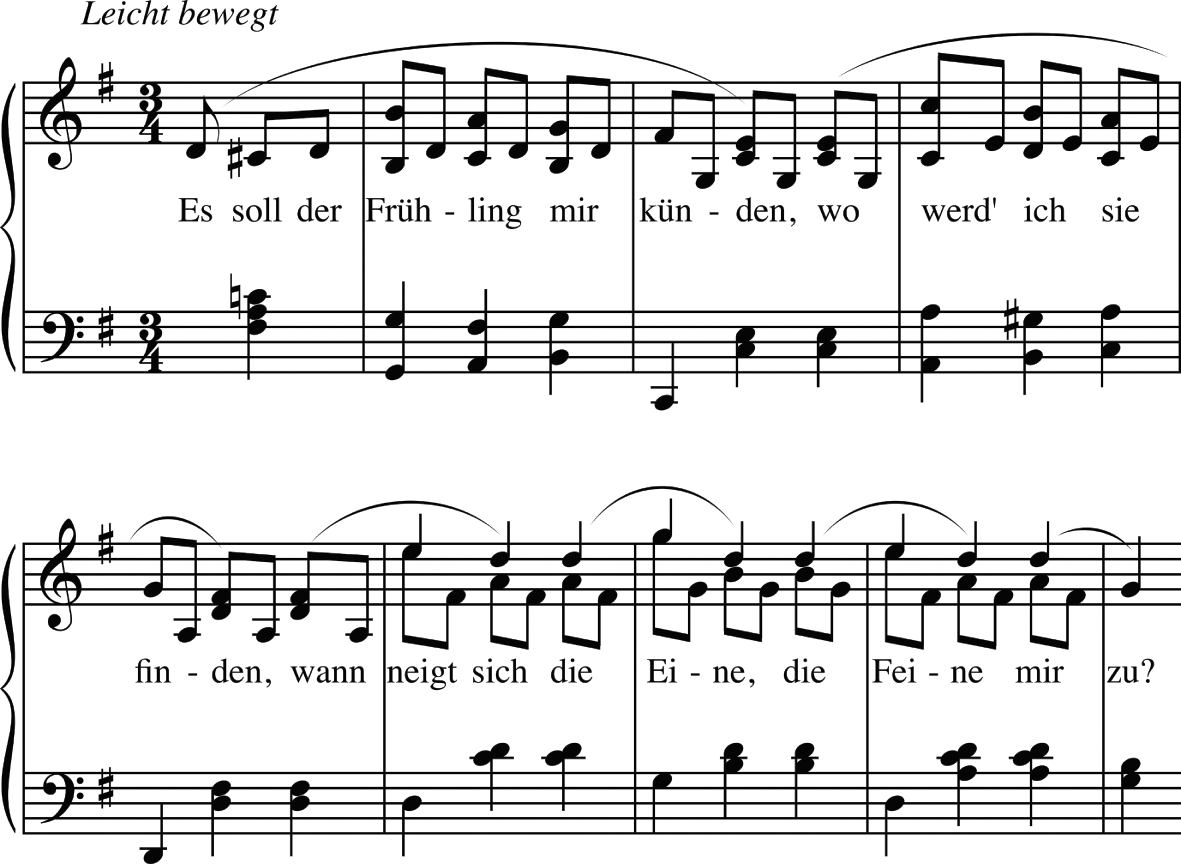

Another problem could occur when dealing with a composer like Lehár, whose practice it was to set pre-written lyrics to music. This might prompt him to find a musical device that would add significance to a word. For example, in the duet ‘Wer hat die Liebe uns ins Herz gesenkt’ in Act 2 of Das Land des Lächelns, Lehár, working from Fritz Löhner’s lyrics, gives unexpected harmonic colour to the word ‘Harmonie’ when Lisa and Sou-Chong sing about there being a paradise-sent harmony between them. In Harry Graham’s English version for Drury Lane, Lehár’s chord remains unexpected, but the reason for its presence is inexplicable in terms of the new lyrics (Example 2.1). Graham was an important British lyricist, who began writing lyrics for musical comedies during the First World War and enjoyed his biggest success with The Maid of the Mountains. He was clearly at a loss in this instance, even though he was fluent in French and German, and created English versions of Madame Pompadour, The Lady of the Rose, Katja, the Dancer, The Land of Smiles, Casanova, White Horse Inn, and Viktoria and Her Hussar.

Example 2.1 ‘Wer hat die Liebe uns ins Herz gesenkt’, Das Land des Lächelns.

Harry B. Smith was among the leading adapters of operetta from the German stage for Broadway. He had the advantage of having collaborated many times with Reginald De Koven and Victor Herbert.Footnote 39 Smith, whose brother Robert often partnered him as a lyric writer, was admired by Charles Frohman, who engaged him for Broadway productions of The Siren (Fall), The Doll Girl (Fall), and The Girl from Montmartre (Berény). Smith set out some ground rules for lyric writing. The musical play should be constructed ‘so the lyrics can carry the action’.Footnote 40 The lyricist has to supply words that not only have sense and rhyme, but ‘must fit the notes perfectly, be correctly accented and have the right vowel sounds for certain tones’.Footnote 41

Besides the Smith brothers, prominent Broadway librettists and lyricists were: Harold Atteridge, who created the American version of The Last Waltz and worked on over twenty shows for the Shuberts; the actor and producer Dorothy Donnelly, who often collaborated with Sigmund Romberg; and Stanislaus Stange, who spent his early life in Liverpool before emigrating to the USA in 1881, and whose English version of Der tapfere Soldat as The Chocolate Soldier was performed in both New York and London. It departed considerably from Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man, which was its source, and B. W. Findon, editor of The Play Pictorial, remarked that ‘only in the first act is the musical version at all like the play’.Footnote 42

‘The lyrics of your song being written … the next consideration is the melody’, Charles Harris instructed his readers in 1906.Footnote 43 But musical theatre began to depart from such advice, especially in the 1920s. The tune now came first, and lyrics were tailored to fit its melodic phrases. Lyricists P. G. Wodehouse, Lorenz Hart, and Ira Gershwin were influential exponents of such practice on Broadway. Kálmán’s normal method was to compose the music and have words set to it, in line with Broadway practice. Musical numbers in his manuscripts sometimes have no words.Footnote 44 Lehár, Straus, and Fall preferred to compose melodies to an existing text. Lehár explained that the book and lyrics suggested to him the overall musical character of an operetta.Footnote 45

‘Manhattan’ (1925) was a pioneering song in which Lorenz Hart demonstrated how sophisticated lyrics – with internal rhymes, such as ‘And tell me what street compares to Mott street in July’ – could fit and enhance the musical phrases of Richard Rodgers’s melody. Internal rhyming, in itself, was not new: in Robert B. Smith’s lyrics to the song ‘Lilac Domino’ (from the 1914 operetta of that name), the phrase ‘flutter by’ appears in the middle of a line and rhymes with ‘butterfly’ at the end of the previous line.

When putting words to an existing melody, an internal rhyme is generally prompted by the repetition of a short musical phrase. Writing lyrics to fit a composer’s tune often made it impossible to make lines scan. Instead, a lyricist would find a means of matching the musical phrasing and the accented notes.Footnote 46 Skilful lyricists would also consider which vowels might best suit held notes, avoid lots of consonants in rapid passages or legato melodies, place diphthongs carefully, and take into account the pitch at which a word is to be sung.

‘Improving’ on Earlier Productions

Basil Hood explained the problems he faced in making an operetta from the German stage meet the expectations of a West End audience:

I may say that the difficulties … come chiefly as a natural consequence of the difference in taste or point of view of Continental and English audiences; that, from the English point of view, the Viennese libretto generally lacks comic characters and situations, the construction and dialogue seem to us a little rough or crude, and the third act … is to our taste as a rule so trivial in subject and treatment that it is necessary to construct and write an entirely new act, or to cut it away altogether, as we have done in ‘Luxembourg’.Footnote 47

He was of the belief that a national culture shaped aesthetic sensibility. He was, therefore, guided by what he imagined to be English taste when revising continental European operetta. Whether there was really a difference in taste, rather than audience expectations is a moot point, and nobody can regard taste as an unproblematic concept after Pierre Bourdieu’s elaborations on this topic.Footnote 48 It is not known how Hood reacted when Glen MacDonough subjected his version of The Count of Luxembourg to further revisions to suit an American audience.

Hood was keen to point out that the activity on which he was engaged differed from translation: ‘a translation would not suit or satisfy the taste of our English audiences … because [they] desire different methods of construction and treatment’.Footnote 49 West End audiences preferred one interval, rather than a second interval followed by a short third act. Hood was particularly worried by Act 3, which in its 1909 version (Lehár later revised it) was barely twenty minutes long, including dialogue. He claimed that, in his version, fewer than thirty lines of dialogue were translated from the German. His task, as he saw it, lay in taking a stage story told in one manner and re-telling it in another, preserving essential situations, but arriving at them and developing them in a different way. In doing so, proper regard needed to be paid to the existing music, but consideration had also to be given to any additional numbers that the new structure might demand. One big structural change occurred at the end of Act 2, when Angèle and René discover each other’s true identity.

This particular episode was in the original treated musically, with a full stage, being the subject of the Finale of Act II; and in doing away with the third act it became necessary, of course, to sacrifice this Finale and to approach and develop the dramatic moments of the recognitions by different methods, in spoken dialogue.Footnote 50

Hood insists that he regarded both Willner and Lehár as collaborators in his adaptation and visited them several times in Austria for friendly consultations. Willner was not new to revising this libretto, because it was already a reworking by himself and Robert Bodanzky of an earlier libretto he had written with Bernhard Buchbinder for Johann Strauss’s Die Göttin der Vernunft (1897).Footnote 51

Hood introduced new minor characters and made Brissard a much more significant character, tailored to suit comedian W. H. Berry. He confessed that, in consequence, ‘new situations and scenes have arisen which do not exist in the original’.Footnote 52 There were plenty of interpolated numbers, too (Table 2.1). Lehár was not entirely happy about the changes made to his operettas in London, and complained to an American reporter that no producer would think of changing a piece by Gilbert and Sullivan.Footnote 53 However, he was not averse to revising his own work. The 1937 publication by Lehár’s self-owned Glocken Verlag had twenty-two numbers compared to eighteen in the 1909 version published by Karczag and Wallner.Footnote 54 Notable additions were the trio ‘Ach, she’n Sie doch’ in Act 2 and the song ‘Alles mit Ruhe genießen’ in Act 3. There were also some structural alterations: the Count makes his entrance, with a new song, as part of the first number instead of entering during the fourth number. Act 3 ended with a short closing song in 1909, whereas in the later edition there is a ‘finaletto’. Lehár would have some justification, however, for thinking that his carefully crafted second act finale had been ruined in Hood’s version. Stefan Frey likens the dramatic weaving in and out of melodic themes (in the context of the characters’ hidden identities) to ‘a kind of diminished Wagnerian leitmotiv opera’.Footnote 55 Where Lehár gave the drama to the music, Hood gave it to the spoken word.

Table 2.1 Interpolations and alterations in The Count of Luxembourg at Daly’s Theatre.

| Number | Title | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| No. 2 | ‘Bohemia’ | Song for Brissard and chorus, which takes the place of a duet for Juliette and Brissard (‘Ein Stübchen so klein’), which becomes No. 20, ‘Boys’ in London. |

| No. 5 | ‘A Carnival for Life’ | Duet for Juliette and Brissard. |

| No. 8 | ‘Cousins of the Czar’ | Duet for Angèle and Grand Duke. |

| No. 10 | Finale of Act 1 | The valse moderato (‘Bist Du’s lachendes Glück’) is transposed down a tone (from G to F). Closing march and song reprises No. 5 before ending with reprise of the No. 4 (the Count’s entrance song). |

| No. 11 | Valse-Intermezzo | Act 2, opening scene and dance. |

| No. 12 | Entrance Chorus and Solo | Angèle’s opening song of Act 2 transposed down a tone. The ‘Versuchung lockt’ section is omitted. |

| No. 12a | Fanfare | |

| No. 12b | Stage Music (waltz) | |

| No. 13 | ‘Pretty Butterfly’ | Song for the Grand Duke. |

| No. 15 | ‘In Society’ | Duet for Juliette and Brissard. |

| No. 16 | ‘Love Breaks Every Bond’ | Duet for Angèle and René, No. 10 in the 1909 version, here transposed down a semitone. Slight changes occur at the end of the waltz duet, then the music is transposed down a tone, rather than semitone, for the duple-time ‘Now I’ve No Ears’ (‘Ich denk’ wir lassen die Astronomie’ in Vienna). It continues down a tone for the final reprise of the valse moderato ‘Say Not Love Is a Dream!’ (‘Bist Du’s lachendes Glück’). |

| No. 17 | ‘Kukuska!’ | Russian Dance. |

| No. 19 | ‘Are You Going to Dance’ | No. 11 in Vienna, but instead of a duet for Juliette and Brissard (‘Schau’n Sie freundlichst mich an’) it is now a duet for Angèle and René. This, in London, was the ‘staircase waltz’. |

| No. 20 | ‘Boys’ | Concerted number for Juliette, Mimi, Grand Duke, Brissard and girls, words by Adrian Ross. (It was No. 2, a duet, in Vienna.) |

| No. 21 | Finale of Act 2 | Reprise of ‘Say Not Love Is a Dream’ and the staircase waltz. |

George Edwardes believed in ‘improving’ continental European productions and informed the Manchester Evening Chronicle that he had succeeded in doing so.

In presenting a play, the English can out-rival the Continent. Take The Merry Widow as it was before a Viennese audience; the play could not be recognized in England, the presentation in this country was so much superior. … The sense of beauty and prettiness is developed on the English stage in a far larger degree than in Continental theatres.Footnote 56

Of The Dollar Princess, he boasted that he ‘bought it’ and ‘altered it’.Footnote 57 Basil Hood wrote the book, and Adrian Ross the lyrics. The changes agreed with the predilections of the British audience, because the operetta achieved 428 consecutive London performances compared to 117 over a period of six years in Vienna.

In the German version by A. M. Willner and Fritz Grünbaum (after a comedy by Gatti-Trotha), John Couder, a millionaire living in New York, has made his money from coal. Wealthy coal industrialists being familiar in the UK, something more distinctly American was needed. In the Manchester try-out, Phineas Conder was an oil tycoon and the father of Alice, the ‘dollar princess’.Footnote 58 In the West End, his name was changed to Harry Q. Conder, and, because the part was given to Joe Coyne (who lacked the technique to sing the romantic role of Freddy), Alice became his sister (played by Lily Elsie). Conder takes pleasure in hiring European aristocrats as servants, and Alice has fallen in love with her aristocratic English secretary, Freddy, but he is too proud to marry her for money (echoes of Danilo, there). Conder is attracted to a visitor who claims to be a Russian princess but is, in fact, a ‘lion queen’ in variety performance. A new character, Bulger, was added in London to show off the talents of comedian W. H. Berry. Act 3 was set in Freddy’s bungalow in California, instead of a country house in Canada, and slight changes were made to the storyline. Alice does not pretend to have lost all her money, and there is no suggestion that Freddy has become a wealthy man. When they meet again, he tells her that he is leaving for home. She tells him she cares no more for gold without love in her heart, and they make up.

The Broadway version had a rewritten book by George Grossmith, Jr, in which Alice returns to being the daughter of a coal millionaire, now named John W. Cowder. The opening number retains the chorus of typists (as in the German version), whose tapping is imitated in the music. In the West End this musical representation was ignored (see Chapter 1). The setting of Act 3 is the Franco-British Exhibition in London, a change of scene that indicates the differing directions in which British and American audiences looked for stimulating distant locations. The Broadway version had two extra songs by Jerome Kern in Act 3. In the Vienna version, this final act was set in Aliceville, Canada, once important for maple syrup, but deserted today.Footnote 59 It was probably chosen to suggest that Freddy still has Alice in his thoughts, but those working on the English versions saw no appeal in Aliceville.

A scene in Act 3 of the West End production illustrates the kind of topical humour incorporated into English versions.Footnote 60 Dick wants to stop his cousin Conder marrying Olga from the Volga, because he is aware of her real profession, and ‘it isn’t right for a lady who tames lions to marry into our family’. Conder’s confidential clerk, Bulger, tells Dick that knowing this will not prevent the marriage, because Conder is ‘very fond of lions, he drinks their tea’. The original Lyons Tea Room at 213 Piccadilly had been a high-status affair, but gradually Lyons had been expanding to cater for those of lower social standing. In 1909, the year of the operetta’s London performance, Joseph Lyons began opening a chain of modest tea shops in the West End called Lyons Corner Houses.Footnote 61 Thus, the joke would be picked up by everyone in the audience. Bulger and Dick decide that it would be a good idea to tell Conder that Olga is a dangerous Bolshevik whose special mission is ‘to blow up all multi-millionaires in America’. Ironically, it was not long before the Lyons Corner Houses became meeting places for political agitators.Footnote 62

The scene for Dick and Bulger also incorporates gags that are added neither for satirical reasons, nor for the purpose of advancing the action. One of the jokes has remained current for many years, although it is difficult to say how fresh it was in 1909.

Bulger: My mother once went to the West Indies.

Dick: Jamaica?

Bulger: No, she went of her own accord.

It should be borne in mind that this was from the pen of Basil Hood, and that ad lib gags were frequently added by comic performers.

A West End production praised for humour was Katja, the Dancer (given with few changes on Broadway as Katja). A London critic declared it ‘full of comedy, really amusing and mostly original stuff’.Footnote 63 Although nothing seems to date as rapidly as comedy, I quote some examples to demonstrate its various types of comic dialogue:

A dumb reply: What comes first on the programme?

No. 1

A sarcastic reply: We must go to some open country, where men are men.

And will you be there, dear?

A bizarre reply: You look very happy.

Happy? I have to get up in the middle of the night to laugh!

It was not a succession of gags, however, and Findon commended its dramatic narrative: ‘I am trying to think if any piece had been produced at the Gaiety with a story so complete in itself, so logically developed as “Katja, the Dancer”.’Footnote 64

Interpolated Numbers

Until around 1840, it was common for British and American audiences to hear interpolated numbers in operas. In earlier times, it was usually a singer who decided to include them: for instance, Maria Garcia (later, Madame Malibran) chose to sing ‘Home, Sweet Home!’ (lyrics by John Howard Payne, music by Henry Bishop, 1823) as an encore in Act 2 of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia in New York, in 1825.Footnote 65 The practice was discontinued in opera, but freshly composed production songs were regularly interpolated in operetta, usually because of the desire to cater for the skills of particular singers (comedians, in particular). In 1906, Charles Harris offers advice on this type of composition in his instruction manual How To Write a Popular Song, pointing out that it often has to fit in with scenic effects or stage business.Footnote 66

Sometimes the score’s original composer contributed new numbers. Lehár was willing to add new songs, such as ‘Cosmopolitan’ and ‘Love and Wine’, for Gipsy Love in London. More usually, another composer located in the city of production was engaged for this task: Jerome Kern supplied two extra numbers for the Broadway Dollar Princess. Sigmund Romberg and Al Goodman provided additional numbers for Kálmán’s Countess Maritza, and Romberg composed additional songs to Gilbert’s The Lady in Ermine, which, as The Lady of the Rose in London, had already been given an extra song by Leslie Stuart. New York critic Alexander Woollcott, remarks wryly of the 1922 production of Fall’s The Rose of Stamboul that upon the original score ‘there seems to have fallen one Sigmund Romberg, a local composer, and now the piece is adorned at intervals with songs that Vienna has yet to hear’.Footnote 67 In Austria and Germany, it was not uncommon for revived operettas to be given new numbers, for instance, ‘Ich hol’ dir vom Himmel das Blau’ was added for Fritzi Massary in the 1928 Charell production of Die lustige Witwe.

Another reason for interpolation was to introduce a fashionable musical style that the main composer lacked the skill to provide, which is why Kern was in demand on Broadway. When Robert Stolz’s Mädi (1923) was produced in London as The Blue Train in 1927, it included ‘Hop Like the Blackbirds Do’, one of several interpolated numbers by composer, lyricist, and actor Ivy St Helier (real name, Ivy Janet Aitchison). This song demonstrates a familiarity with syncopated rhythms not shown by Stolz at this time. His previous London production Whirled into Happiness (1922) contained a song ‘New Moon’ marked ‘Tempo di fox-trot’ but lacking syncopation.

It was not always clear what extra contributions had been written and by whom. An unwary critic of the Daly’s revival of A Waltz Dream in 1911 confessed that he did not find the music as alluring as in 1908, but added, ‘the most individual and attractive things of all are in the third act, where we come to Princess Helena’s last song and its delightful introduction’. This particular song, ‘I Chose a Man to Wed’, was actually one of the interpolated numbers supplied by Scottish composer Hamish MacCunn (who conducted the performance) as part of a rewritten Act 3.Footnote 68

An American reviewer of Fall’s Lieber Augustin in 1913 is more cautious. He praises the ‘succession of very delightful melodies’, but adds:

It is getting to be a habit to praise Mr Leo Fall’s music, and in some respects a bad habit, since a counter-claimant for a ‘song-hit’ is reasonably sure to bob up before many hours pass. Wherefore the announcement that Mr Leo Fall’s music in this piece is entirely charming and appealing must be taken to include any others who may have assisted.Footnote 69

Another critic suspects, on hearing the New York adaptation of The Last Waltz, that some of the numbers are not by Oscar Straus: ‘There are several interpolated numbers, unidentified except by internal evidence. You suspect “Charming Ladies” and “A Baby in Love” of having been baptized in the East River rather than the blue Danube.’Footnote 70 Both of these songs were, in fact, interpolated numbers by Alfred Goodman.

Substantial Changes

Sometimes, it was felt necessary to rework a libretto in a radical manner. In Chapter 6, the wholesale changes made for the MGM film of The Chocolate Soldier are discussed, but even Stanislaus Stange’s Broadway version had been, just like Rudolf Bernauer and Leopold Jacobson’s Der tapfere Soldat, a liberal reworking of George Bernard Shaw’s Arms and the Man (1894). George Edwardes admitted that he had turned down an opportunity to acquire the rights because he was worried that Bernard Shaw would become litigious and bring an injunction against him.Footnote 71 A reviewer in the New York Times remarked that the operetta was ‘more Shavings than Shavian’ and continued:

Mr Shaw cabled last night that if the audience was pleased with the entertainment they should congratulate themselves, and it is not unlikely that his advice was followed by the greatest number of those present. For there is enough broad fooling to the action to make it appealing to people who do not care for Shaw, and enough bright and spirited music to make it worthwhile to those who do, but who now find they must take a good deal of his play for granted.Footnote 72

Kálmán found that substantial changes in English versions of his operettas reduced his income from royalties. In the London production of Autumn Manoeuvres (1912), only three of his numbers survived, as five other composers were involved (including musical comedy composers Monckton and Talbot). Henry Hamilton’s book and lyrics clearly departed considerably from Robert Bodanzky’s Ein Herbstmanöver for Vienna (1909) – and that production was, itself, an adaptation of the Hungarian Tatárjárás, given at the Vigszínház Theatre, Budapest (1908), which had a book by Károly von Bakyonyi and lyrics by Andor Gabor. Kálmán lost further royalties after the outbreak of war. Rida Johnson Young had reworked Gold gab ich für Eisen as Her Soldier Boy for Broadway in December 1916, cleverly overcoming its implausible incident of a mother who fails to realize an imposter is impersonating her son, by having her go blind. It was well received and still running when the USA entered the First World War in April 1917. As Soldier Boy!, it also ran in the West End in 1918, its origins unnoticed by the censors, who may have been distracted by the interpolated soldier’s song ‘Pack up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag’ (George and Felix Powell), which was already present in the Broadway production.Footnote 73

P. G. Wodehouse and Guy Bolton, who had made a successful Broadway version of Kálmán’s Die Faschingsfee as Miss Springtime in 1916, were surprised at the flop of their adaptation of Kálmán’s Die Csárdásfürstin as The Riviera Girl the next year. The USA was now at war, so they changed the Hungarian and Austrian scenes to Monte Carlo.Footnote 74 The Riviera Girl had a lot going for it: as with Miss Springtime, it was a lavish Klaw and Erlanger production, with scenery designed by the skilful Joseph Urban, and was given at the New Amsterdam Theatre. Wodehouse and Bolton did not criticize the score, which they admired, and shouldered the blame for its failure themselves, deciding that they had been ‘too ingenious’ in devising a plot to replace the existing libretto, which they held in low regard.Footnote 75

The Cousin from Nowhere had stuck closely to the Berlin version of Künneke’s operetta when given in the West End. It had a book by Fred Thompson, and lyrics by Adrian Ross, Robert C. Tharp, and Douglas Furber. It retained the location of the Netherlands, and the stranger who arrives on the scene has supposedly spent several years in Batavia, on the island of Java, which was the most important trading city of the Dutch East Indies (since 1945, the city has been known as Jakarta, capital of the Republic of Indonesia). However, the Broadway version shifted attention onto the leading female role and transplanted the action into Virginia during the American Civil War. It was now titled Caroline and was summed up by its librettist Harry B. Smith as the story of a Southern Cinderella in love with a Yankee officer.Footnote 76

The ‘In Batavia’ quintet became ‘Argentine’.Footnote 77

It is a fox trot, not a tango, but that makes sense since the stranger (Bob) is the only one who claims to have experienced the Argentine. The tango rhythm of ‘Weißt du noch?’ now has particular relevance in the duet ‘Sweethearts’, because of Bob’s supposed sojourn in Argentina.

Violet: Can it be you’re the boy I used to know in the days departed?

Bob: Can’t you see I am still the same, the years passing by have changed me so?

There are also two interpolated numbers: ‘Some Day’ (a slow waltz), with words by Adrian Ross and Smith, and music by Benatzky; and ‘Way Down South’ (a fox trot, but not labelled as such), with words by Smith, and music by Alfred Goodman.

The changes were substantial in Caroline, as they were, also, in the rewriting of Zigeunerliebe as Gipsy Love for the West End. Edwardes commissioned Hood to rework the piece and persuaded Lehár to write new numbers. Edwardes commented in an interview:

The piece will be an entirely new one. The dream business is all gone. Originally, the first and third acts were reality. The second was dreamland. Captain Basil Hood has written me an entirely new book. The first act is laid in the garden of a Roumanian noble’s palace. The second takes us to a wine-shop. The third is the Summer Hall of Roumanian Grandee, the work of Joseph Harker.Footnote 78

In Willner and Bodanzky’s version, the whole of the action of Act 2 turns out to be Zorika’s dream of Gipsy life. In discussing Zigeunerliebe, Heike Quissek categorizes the anticipation of events through a dream as a special form of fairy-tale vision.Footnote 79 In Act 3, Zorika wakes up, and no longer wishes to rebel against bourgeois social convention. The Gipsies represent freedom from the regulations of bureaucratic society, their rules are in the heart, as Jozsi says. Gipsy love, however, turns out to be a fantasy in which faithfulness plays no part. In the end, Zorika rejects freedom from rules for her reliable suitor Jonel.

In Hood’s version, as Findon explains to readers of The Play Pictorial, the adventures of Zorika, now named Ilona, no longer take place in a dream: ‘the dream has materialized and Ilona actually goes through the episodes which end in her return to her father’s house a chastened and penitent girl, ready to appreciate the calm happiness of a peaceful existence and the love of an honest and courteous gentleman’.Footnote 80 Hood gave his reason for rejecting the ‘dream’ act:

I did not like the root idea of Ilona’s elopement with the gipsy being a dream. English audiences do not care for dream plays. They resent the discovery in the last scene that they have been spoofed.Footnote 81

In addition, Hood created new male and female comic roles, for, as Findon remarks, however much the appreciation of ‘good-class music’ had increased, the public still could not accept an operetta that was not ‘well punctuated with the humorous sallies of the light-hearted comedian’.Footnote 82 Gertie Millar was cast as Lady Babby, and W. H. Berry as Dragotin. Hood was proud of his achievement and believed Lehár recognized how much he had improved upon the Vienna version, claiming that the composer was ‘so struck with my version of Gipsy Love that he asked me if I would be agreeable to it being translated into French and German for presentation on the Continent, in preference to the original version’.Footnote 83 However, when Lehár put together the final revisions of his operettas for Glocken Verlag, he decided against Hood’s version.

Occasionally, an operetta’s subject matter could be politically delicate. In Song of the Sea (1928), Arthur Wimperis and Lauri Wylie reworked the libretto by Richard Bars and Leopold Jacobson to Künneke’s Lady Hamilton (1926). In the German version, Amy Lyons flirts with a Spanish naval officer Alfredo Bartos, but leaves for London with Lord William Hamilton. Later, Alfredo ends up as a prisoner of war, but Amy becomes Lord Nelson’s mistress and obtains his release (although she remains with Nelson). To succeed in the West End, it needed to be sensitive to the British political context in which the naval hero Lord Nelson was held in high esteem. Thus, in the English version, the heroine is Nancy, courted by Richard Manners, a lieutenant of the Royal Navy. She is persuaded to go to London with Sir William Candysshe to be surrounded in luxury, but without promise of marriage. Later, installed at the British Embassy in Naples, an altercation occurs between her former and present lovers. Richard is imprisoned, but Nancy craftily obtains his release, and the implied ending is a marriage between herself and Richard.

Schubert’s Variegated Blossoms

A person who translates lyrics is, to a certain extent, in a similar position to those who write lyrics to existing music, except that, in the former case, the music already has lyrics in another language. However, in Das Dreimäderlhaus it may be that Heinrich Berté is, at times, trying to fit already existing music to already existing lyrics. That is because Berté had originally composed the music himself; however, when doubts began to arise about the suitability of his music, he was asked to use Schubert’s music instead. He was angry at first, especially when this caused his publisher to demand the repayment of an advance, but a deal was done that recompensed him for his work as arranger.Footnote 84 The Broadway and West End versions, Blossom Time and Lilac Time, both present different reworkings of Dreimäderlhaus and must have involved significant collaboration between Sigmund Romberg and Dorothy Donnelly in the first case, and George Clutsam and Adrian Ross in the second.

The Nazi Lexikon der Juden in der Musik (1940) finds it necessary to explain why the party appears to be banning Schubert’s music by proscribing this stage work.Footnote 85 It points out that Berté [born Bettelheim] was Jewish and so were his librettists, Alfred Willner and Heinz Reichert. To demonstrate objectivity, a court order is quoted, stating: ‘the music of Franz Schubert has been presented throughout in such a way that it could no longer be called Schubert’.Footnote 86 Yet there is less manipulation of Schubert’s music in Berté’s operetta than in its successors, Blossom Time and Lilac Time. Recognition of a change to a Schubert composition can be mistaken. In Act 2, Hannerl und Schober’s duet uses the melody of the second movement of Piano Sonata in A Minor, D537 (1817) at ‘Mädel sei nicht dumm’. Schubert revised this melody for the Rondo of his better-known A Major Sonata, D959 (1828), but Berté used the earlier version.

Blossom Time was one of the Shuberts’ most successful shows,Footnote 87 and extensive holdings for it are in the Shubert Archive. Romberg goes further than Berté in cutting, pasting, and changing. He replaces some of the numbers with his own compositions (for example, ‘There Is in Old Vienna Town’ in Act 1, ‘Let Me Awake’ in Act 2, and ‘Keep It Dark’ in Act 3), and he adds a saxophone to the score. He replaces other numbers with more familiar compositions of Schubert: for example, ‘Die Forelle’ (The Trout) and ‘Ständchen’ (the Serenade from Schwanengesang) in the Act 1 ensemble ‘Good Morning’; ‘Heidenrösslein’ in ‘Love’s a Riddle’ (Act 2); and ‘Ave Maria’ in ‘Peace to Your Lonely Heart’ (Act 3). ‘Speak, Daisy, Yes or No!’, in Act 2, is an example of Romberg’s cutting and pasting: he bases the opening notes on bars 3–5 of the first subject of the second movement of the Unfinished Symphony and the second phrase on bar 15.

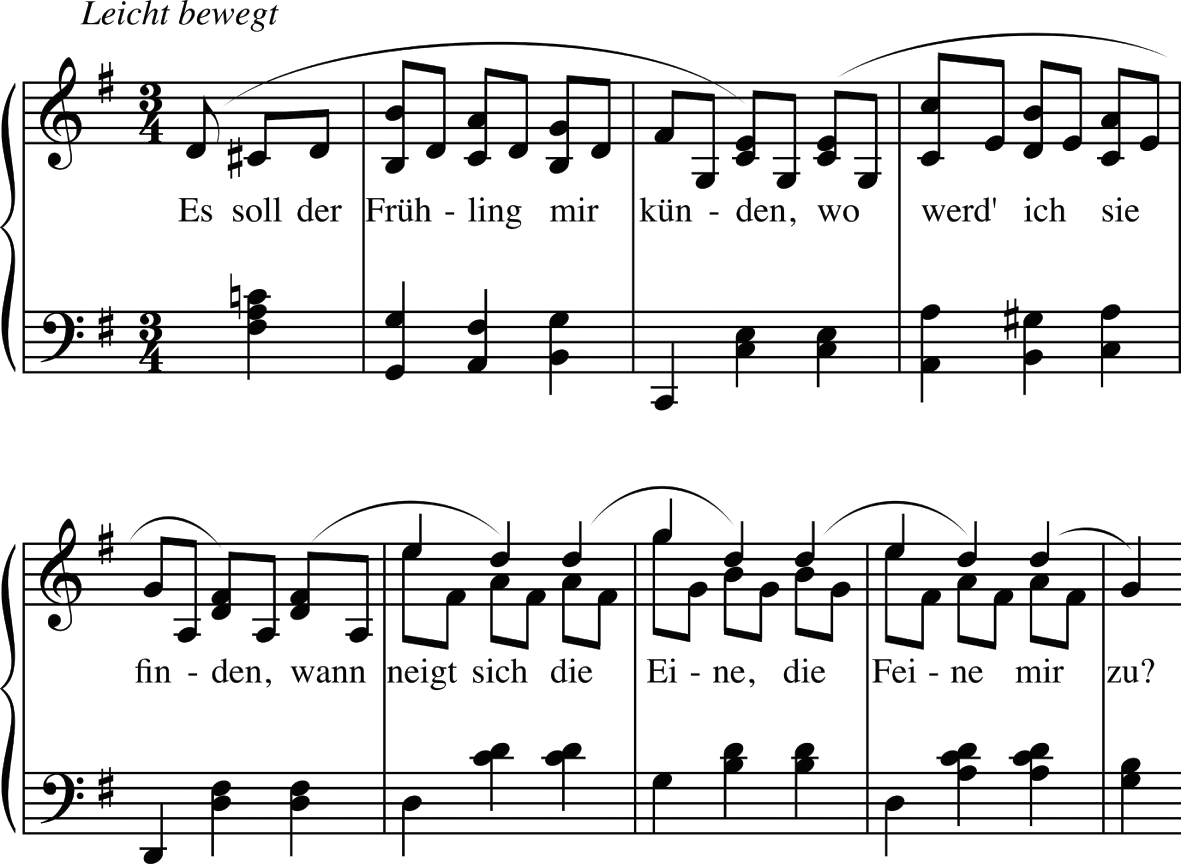

Two examples illustrate how Romberg occasionally reworked material substantially. The quintet ‘My Springtime Thou Art’ in Act 1 makes use of Waltz D365, No. 2, which featured in a similar quintet in Das Dreimäderlhaus. Berté remained close to Schubert’s piano piece, but Romberg changes metre, first giving it a rhythmic syncopated character and then converting it into a polka (Examples 2.2 and 2.3).

Example 2.2 ‘Es soll der Frühling mir künden’, Das Dreimäderlhaus, Act 1.

Example 2.3 ‘My Springtime of Love Thou Art’, Blossom Time, Act 1.

Most striking, perhaps, is the way Romberg managed to create a hit song, ‘You Are My Song of Love’, out of the second subject of the first movement of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony. This tune features in Das Dreimäderlhaus and Lilac Time, too, but it is not long enough in itself to fill the requirements of a song. Romberg’s solution is to insert a ‘middle eight’ taken from the seventh of Schubert’s German Dances, D783. None of this troubled a New York Times critic in 1921, who had paid tribute to Blossom Time, claiming it had ‘done service to his [Schubert’s] memory for musicians today’.Footnote 88

Clutsam had enjoyed a modest success in 1916–17 with Young England, an opera co-composed with Hubert Bath to a libretto by Basil Hood, but this paled into insignificance compared to the success of Lilac Time. Clutsam published a short biography of Schubert in the same year as the production of Lilac Time and he began with the statement: ‘There is no more pathetic and touching career recorded in musical history that that of Franz Peter Schubert, and there are few composers whose works contain slighter trace of their personal history.’Footnote 89 Like Romberg, Clutsam replaces some of the rarer Shubert melodies with those more familiar, including several chosen by Romberg, such as ‘Die Forelle’ in ‘The Golden Song’ (Act 1), ‘Ständchen’ (Act 2), and ‘Heidenrösslein’ in ‘My Sweetest Song of All’ (Act 3). He also includes a variant of bars 47 onwards of Impromptu No. 4, D899 in the new quartet he adds to Act 1 (‘Four Jolly Brothers’). He adds a Prelude to Act 2 making use of ‘Die Post’ from Schwanengesang, and the first subject of the first movement of the Unfinished Symphony. Later, he uses the third of the Six Moments Musicaux, D780, for a dance of bridesmaids and children. Like Romberg, he is tempted to change metre. The sextet ‘When Skies Are Blue’ is a 2/4 version of the 3/4 ‘Wer’s Mädel freit’ in Das Dreimäderlhaus. His most substantial change is the elongated waltz-time reworking of the second subject of the first movement of Piano Sonata in E♭ Major, D568 for the refrain of ‘The Flower’. Berté had used the melody for ‘Liebes Schicksalsblümlein spricht’, No. 9 of Das Dreimäderlhaus, and in Clutsam’s own copy of the vocal score of that work he has written ‘valse’ at this point (Figure 2.1 and Example 2.4).Footnote 90

Figure 2.1 Clutsam’s copy of the vocal score of Das Dreimäderlhaus.

Example 2.4 ‘Tell Me, Dear Flower’. Clutsam’s waltz-time arrangement in Lilac Time.

A Diminishing of Revision in the 1920s and 1930s?

In the 1920s and 1930s, revisions for stage productions were rarely as substantial as in the earlier years. Tobias Becker cites the West End productions of Das Land des Lächelns and Im weißen Rössl as evidence that a more literal form of translation took over in the 1920s.Footnote 91 In the 1930s, there developed a concept of operetta production as a homogeneous whole made not only of music and text but of stage sets, costume, and choreography, all of which should be retained in some way. This idea persuaded impresarios to purchase not just the production rights, as they had done in the past, but everything connected to the original production, including performers, directors, and designers. Oswald Stoll was one of the first to do so, when he presented White Horse Inn and Casanova at the London Coliseum, replicating the spectacular productions seen at Berlin’s Großes Schauspielhaus. This was a foretaste of the ‘lock, stock and barrel’ transfers of late twentieth-century musicals, such as Cats, Phantom of the Opera, and Les Misérables. White Horse Inn became one of the most successful operettas globally, with initial runs of over 650 performances in London, and over 700 in Vienna and in Paris. Like some other operettas, it derives humour from the culture clash between city and countryside. The unusual thing in this case being that the cosmopolitan space – the hotel – is situated in the country rather than the city.

In the Berlin version, Leopold, the head waiter, loves Josepha, owner of the inn in St Wolfgang, but she prefers Dr Siedler, a Berlin solicitor. Siedler, however, has his eye on Ottilie, daughter of Berlin businessman Wilhelm Giesecke. Sigismund, the son of Giesecke’s business rival, has been told to ask Ottilie to marry him, but he flirts with another woman, Klärchen, and Ottilie goes off with Dr Siedler. It takes none other than the Emperor Franz Josef to sort things out, enabling Josepha and Leopold get together in the end. Having featured historical characters in his two previous revue operettas, Erik Charell asked his co-librettist Hans Müller-Einigen to include a part for the Emperor, whose summer residence had been in Bad Ischl, not far from St Wolfgang. Müller-Einigen had worked in Hollywood in the 1920s and shared Charell’s desire to create a spectacular modern operetta. The modernity was evident in the fashionable costumes (contrasting with the folk costumes of the locals), the jazz band on stage, and the latest theatre technology, which was used to create thrilling effects (see Chapter 7). Giesecke no longer manufactures gas mantles as in the play by Oscar Blumenthal and Gustav Kadelburg of 1897; he has a thriving male underwear factory (his garments button up in the front unlike those of his business rival). Grumpy but likeable, Giesecke is a Berliner who contrasts with the openly friendly country folk. The role of Franz Josef was not originally intended to be interpreted in a serious manner, although this began to happen later. Irony and camp were always guiding lights for Charell.

In Harry Graham’s West End version, Giesecke became John Ebenezer Grinkle, his daughter Ottilie became Ottoline, Dr Otto Siedler became Valentine Sutton, a solicitor, and Sigismund Sülzheimer became Sigismund Smith. Graham’s text was not used in New York because it was considered to represent an old-fashioned operetta style,Footnote 92 so David Freeman took charge of the book, and new lyrics were provided by experienced Broadway revue writer Irving Caesar: thus, for instance, ‘It Would Be Wonderful’ became ‘I Cannot Live without Your Love’, and ‘Your Eyes’ became ‘Blue Eyes’, and, in the song praising the White Horse Inn, Wolfgangsee became ‘silver lake’. Names were changed again: Josepha became Katarina (played by Kitty Carlisle), Giesecke became McGonigle, Ottilie became Natalie, Siedler became Donald Sutton an American lawyer, and Sigismund was now a non-singing role, Sylvester S. Somerset from Massachusetts. To give the score an up-to-date Broadway sound, it was re-orchestrated by Hans Spialek, who had worked with Richard Rodgers and Cole Porter.

New music was added, or an earlier song was replaced with another. After the arrival of the tourists in Act 1, a song by Jára Benes was added to allow Katarina to introduce herself. Surprisingly, Stolz’s ‘Good-Bye’, which Charell had interpolated in Act 2 of the West End production, and was one of the show’s hits, was exchanged for ‘Goodbye, Au Revoir, Auf Wiederseh’n’, with lyrics by Irving Caesar to a tune from Eric Coates’s Knightsbridge March. Another of Stolz’s songs, ‘You Too’ was replaced by ‘I Would Like to Have You Love Me’ (lyrics by Irving Caesar and Sammy Lerner, music by Gerald Marks), and, in Act 3, Stolz’s ‘My Song of Love’ was cut and replaced with ‘The Waltz of Love’ by Richard Fall. It would appear that the cutting of Stolz’s music must have been related to a rights issue. Having composed more than one number for Im weißen Rössl, Stolz had gone to court to try to enforce his demand to have his name on the score. He was not successful, except in the UK, where ‘Good-Bye’ had proven so popular.

There is satire of rustic life as well as of city folk in Im weißen Rössl. The countryside offers charming cows and jolly slap dancing; the city offers vanity (Sigismund) and grumpiness (Giesecke). The cow song is a parody of nature-loving sentimentality.

The irony of the cow song appears to have worked in both London and New York, perhaps because of cosmopolitan attitudes to bucolic simplicity.

The Emperor’s appearance as deus ex machina is in keeping with the caricaturing found in this operetta. Norbert Abels describes him as being dragged out of the imperial crypt to set things right.Footnote 93 Josepha tells him her problems, and he replies in his imperial wisdom: ‘Es ist einmal im Leben so, jedem geht es ebenso, was möcht’ so gern, ist so fern’ (It’s like this in every lifetime and the same for everyone: what you really want is out of reach). Yet his words have taken on a serious tone over the years. Tobias Becker goes to the heart of the matter, when he says they are both truth and parody: ‘the mixture is what makes them appealing’.Footnote 94 At a performance at Schloss Haindorf in Langenlois in July 2016, I was surprised to hear many members of the audience simultaneously whispering along with the Emperor as he delivered his words. However, evidence that they were treated seriously in the Broadway production of 1936 is provided by an RCA Radio broadcast that year.Footnote 95

New Operetta Versions of the 1950s and Later

Updating the words and music of operettas introduces the social concerns and sounds of a later period. In one sense, there is a positive quality to updating if the purpose is to demonstrate continuing relevance. However, an audience may also want to enjoy moments when the cultural past itself seems relevant. The link between the time in which these operettas were ‘modern’ and the later age in which we consume them is often the basis of a rewarding experience. When, for example, we hear an operetta of the first decade of the twentieth century decked out in a 1950s musical arrangement, it is usually a recognition of the later decade that dominates. Furthermore, there is often a feeling of mismatch between the workings of an early musical style and a later arrangement. Perhaps that explains why there is no generally accepted concept of Dirigent-Theater to set alongside Regie-Theater. All updated arrangements lock the music into another time frame that, itself, swiftly becomes historic. The main point I wish to make is that we do not just enjoy an operetta because of its relevance to us today, we also take pleasure from its being a social and cultural document that enhances our understanding of the time in which it was written.

The fact remains that operettas have generally been updated when revived. This happened during the 1926–27 season at the Großes Schauspielhaus, when Charell produced revivals of Die lustige Witwe and Madame Pompadour. Nevertheless, there was no musical updating of the disproportionate type found in some recordings of operettas made in the 1970s, such as Die Csárdásfürstin (BMG Entertainment, 1972), Im weißen Rössl (BMG Entertainment, 1974), or the pop version of Die Dollarprinzessin (Phonogram, 1975). Those examples all demonstrate that updating the music creates different problems to updating the book or lyrics.

The arranging and reworking of earlier music found in operettas such as Casanova and Die Dubarry is very different to the desire after the Second World War to update revivals of operettas like Die Dollarprinzessin and Die Csárdásfürstin largely by the simply expedient of increasing the brassy sound and adding a drum kit. Part of what is misguided is that they are thereby clothed in a style that has its roots in the American music that was, in the early decades of the century, heard as contrasting with European traditions. The updating by composers like Benatzky and Korngold was done with care for, and cultural knowledge of, the musical tradition within which they were working. Korngold’s reworking of Strauss Jr’s music in Walzer aus Wien, for example, was in line with the development of that same style of music in the years since Strauss’s death.

New English versions were being published with some regularity from the late 1950s on, designed to appeal to amateur operatic and dramatic societies. Two different English versions of The Merry Widow were published by Glocken Verlag in 1958: one was by Phil Park with musical arrangements by Ronald Hanmer (who transposed much of the music down a tone) and the other by Christopher Hassall based on the edition published by Doblinger in Vienna. Both versions included new lyrics, alterations to dramatic action, and musical re-arrangement. This was the norm for such publications, many of which are revisions by Park and Hanmer: for example, The Gipsy Princess (Chappell, 1957), Waltzes from Vienna (Chappell, 1966), The Dollar Princess (Weinberger, 1968), Lilac Time (Weinberger, 1971), and Gipsy Love (Weinberger, 1980). Other new versions were produced with the aid of Agnes Bernelle, Adam Carstairs, Nigel Douglas, Bernard Dunn, Michael Flanders, Edmund Tracey, Eric Maschwitz, and Bernard Grun. In the 1990s, Richard Bonynge’s recording of The Land of Smiles (1996) used a version by Jerry Hadley, and Paganini (1997) used an English version by David Kram and Dennis Olsen.Footnote 96 A new production of The Merry Widow opened at the Metropolitan Opera in December 2014, with a translation by Jeremy Sams that clearly aimed to be punchy and contemporary: ‘Who can tell what the hell women are?’ sang the men in the familiar ‘Weib, Weib, Weib’ ensemble.Footnote 97 In spite of its Broadway-style internal rhyme, it probably needs updating again.