Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Contributors

- Abbreviations

- Section I The 2006 Military Coup: Impact on the Thai Political Landscape

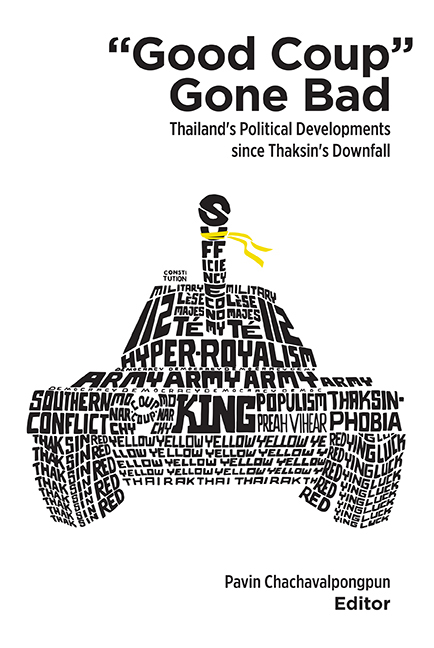

- 1 “Good Coup” Gone Bad: Thailand's Political Developments since Thaksin's Downfall

- 2 Unfinished Business: The Contagion of Conflict over a Century of Thai Political Development

- Section II Defending the Old Political Consensus: The Military and the Monarchy

- Section III New Political Discourses and the Emergence of Yellows and Reds

- Section IV Crises of Legitimacy

- Index

- Plate Section

2 - Unfinished Business: The Contagion of Conflict over a Century of Thai Political Development

from Section I - The 2006 Military Coup: Impact on the Thai Political Landscape

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 October 2015

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Foreword

- Contributors

- Abbreviations

- Section I The 2006 Military Coup: Impact on the Thai Political Landscape

- 1 “Good Coup” Gone Bad: Thailand's Political Developments since Thaksin's Downfall

- 2 Unfinished Business: The Contagion of Conflict over a Century of Thai Political Development

- Section II Defending the Old Political Consensus: The Military and the Monarchy

- Section III New Political Discourses and the Emergence of Yellows and Reds

- Section IV Crises of Legitimacy

- Index

- Plate Section

Summary

INTRODUCTION

Just over an hour after announcing on television that the military had seized power on the evening of 19 September 2006, Army Commander-in-Chief Sonthi Boonyaratglin was photographed on his knees at Chitralada Palace, seeking the blessing of King Bhumibol Adulyadej. By then, the generals' every move had been painstakingly choreographed to impress upon the public the idea that the coup had been staged in the King's name. Yellow ribbons and flowers adorned tanks, uniforms, and assault rifles. Giant portraits of the King and Queen served as the background for major announcements. Royal Commands were read before ornate shrines to their Majesties. The junta's studiously verbose name, the “Council for Democratic Reform under the King as Head of State”, was officially changed more than ten days after the coup, but not before making sure that the people had heard the message loud and clear. Thailand, to be sure, had seen “royalist coups” before, but none as awash in royal symbolism. Then again, the military had never removed a prime minister as popular as Thaksin Shinawatra. As life quickly returned to normal, it was evident that only the appearance of royal sanction could have muted public opposition to the coup, or staved off the possibility that the deposed prime minister might put up any resistance.

The argument made by royalists in support of the legitimacy of the illegal seizure of power springs from a conception of the nation fundamentally at odds with that common to modern constitutional monarchies. Nowhere in particular was the fight against Thaksin defined in more memorable terms than in a speech delivered by General Prem Tinsulanonda — a former prime minister (1980–88) and current president of the Privy Council — at the Chulachomklao Royal Military Academy two months before the coup. Prem famously likened the military to a “horse”, and hastened to add that governments, unlike the horse's actual “owner”, come and go like mere “jockeys”.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Good Coup Gone BadThailand's Political Development since Thaksin's Downfall, pp. 17 - 46Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2014