4.1 Introduction

Energy is the lifeblood of modern society: it is required to fulfil people’s basic needs and everyday activities, and, in the same vein, the world’s economic processes heavily rely on energy. However, global energy consumption and production is putting high pressure on the earth system and is arguably the main culprit behind climate change; fossil-fuel combustion accounts for two-thirds of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and 80 per cent of carbon dioxide (IEA/OECD 2017). Therefore, decarbonization of global energy systems is of paramount importance for a sustainable future, and a global uptake of renewable energy plays a key role in this trajectory (e.g. Ki-moon Reference Ki-moon2011; IRENA 2015; WFC 2016).

While the overall share of renewables in total final energy consumption grew to around 19 per cent and reached a new record in 2017, this growth must accelerate to reach a two-thirds share by 2050 (IRENA 2018a). This is both technically and economically feasible, yet it requires effective global governance to get governments committed, to put regulatory frameworks in place, and to facilitate knowledge exchange and technology transfer (Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). As discussed in Chapter 3, the renewable energy subfield is institutionally complex. It is governed by a wide range of different institutions, including international organizations, alongside private institutions and multi-stakeholder partnerships. On top of that, the subfield covers different renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, and has to navigate three critical challenges, commonly known as energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability (e.g. Cherp et al. Reference Cherp, Jewell and Goldthau2011; Florini and Sovacool Reference Florini and Sovacool2011; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen et al. Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, Jollands and Staudt2012). Finally, the renewable energy subfield is still dominated by national policy making as nation states continue to have sovereign control over the energy domain.

Various studies have introduced mappings of the institutional complexes for climate change (e.g. Keohane and Victor Reference Keohane and Victor2011; Abbott Reference Abbott2012; Widerberg et al. Reference Widerberg, Pattberg and Kristensen2016) and energy (e.g. Sovacool and Florini Reference Sovacool and Florini2012; Wilson Reference Wilson2015; Sanderink et al. Reference Sanderink, Kristensen, Widerberg and Pattberg2018), but only a few zoom in on the institutional complex for renewable energy specifically. This is regrettable, as the subfield is most prominent within the climate-energy nexus and can be characterized as institutionally diverse (see Chapter 3). Furthermore, existing mappings are biased toward public institutions, mostly excluding nongovernmental institutions (e.g. Suding and Lempp Reference Suding and Lempp2007; Barnsley and Ahn Reference Barnsley and Ahn2014; Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). However, recent literature has argued that the global energy transition is driven by bottom-up and polycentric governance rather than through integrated international cooperation (Aklin and Urpelainen Reference Aklin and Urpelainen2018; Meckling Reference Meckling2018). Hence, novel insights are needed into the institutional constellations and dynamics within the renewable energy subfield, to ultimately answer the guiding question: is the institutional complex of renewable energy contributing to the global energy transition in an effective manner?

A first step in the search for an answer to this question is to advance our understanding of the institutional complex and to evaluate coherence and management (as laid out in further detail in Chapter 2). First, coherence is understood as the harmony of institutional features and interactions across institutions toward an overarching purpose. Meso-level coherence, i.e. the level of coherence in the subfield as a whole, is determined based on the following indicators: first, the convergence/divergence among interpretations of the core norm, i.e. to substantially increase the share of renewables; second, the distribution of membership, i.e. a limited or wide range of targeted actors; and third, an (un)balanced allocation of governance functions. Micro-level coherence, i.e. the level of coherence between specific individual institutions, is assessed along the same three dimensions and, more importantly, mechanisms of interactions. These can be distinguished as cognitive (i.e. when knowledge is transferred), normative (i.e. when rules and norms interact), and behavioural (i.e. when impacts of behaviour intersect). Second, management is defined as attempts to deliberately steer interactions between two or more institutions (Zelli Reference Zelli2010), and is merely assessed at the micro level. It is determined based on the levels and agents (e.g. unilaterally or jointly), and consequences of management (e.g. increased harmony of institutional features: core norm, membership, governance functions, interaction mechanisms). Juxtaposing levels of coherence and management enables the characterization of the renewable energy subfield by synergy, coexistence/duplication, or conflict, or rather by division of labour, coordination, or competition (see Chapter 2).

For studying coherence and management at the micro level, three important multi-stakeholder partnerships were selected, since global (renewable) energy governance remains underdeveloped under the umbrella of the United Nations (UN) and in the intergovernmental sphere in general (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen2010; Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). Moreover, the chapter aims to go beyond dyadic relationships between intergovernmental institutions and seeks to analyze the plethora of interconnections among different forms of governance. The selected institutions include the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP), the Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21), and Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL), all of which can be described as transboundary cooperation efforts between public and private actors that aim at addressing a public policy objective (Schäferhoff et al. Reference Schäferhoff, Campe and Kaan2009; Pattberg and Widerberg Reference Pattberg and Widerberg2014).

The analysis builds on three methodological steps: first, a thorough analysis of the institutional constellations, second, a content analysis of official documents and reports of the selected institutions, and third, an analysis of the views of climate and energy experts obtained through semi-structured interviews. The interviewees were staff members of the selected institutions, experts from academia and civil society organizations (CSOs), and government officials, who are closely associated with the respective institutions. Based thereon, this chapter advances our understanding of institutional complexity, specifically for global renewable energy governance. Therewith, it provides insights from which lessons can be drawn for governing the overall climate-energy nexus.

The chapter is structured as follows. Section 4.2 briefly introduces the topic of renewable energy and its centrality. Subsequently, Section 4.3 analyzes the institutional features and measures meso-level coherence for the renewable energy subfield as a whole. Thereafter, Section 4.4 determines micro-level coherence by examining institutional features and interaction mechanisms across the selected partnerships. Finally, Section 4.5 describes attempts to manage these interactions at the micro level, after which Section 4.6 concludes with some final remarks and suggestions for future research.

4.2 Renewable Energy: Providing Sustainable Energy for All

‘We all know that renewable energy is limitless and will last forever’ is what former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon stated in 2016 at the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) Debate in Abu Dhabi.Footnote 1 This statement mirrors the high importance of the role of renewable energy in the world’s trajectory to sustainable development.

Firstly, renewable energy is crucial for satisfying the increasing energy demand. In light of the world’s growing population, energy security is a high priority for governments worldwide (Dubash and Florini Reference Dubash and Florini2011; Van de Graaf Reference Van de Graaf2013), in the way that they wish to ensure an ‘uninterrupted availability of energy sources at an affordable price’.Footnote 2 At present this is particularly challenging, since finite energy sources are depleted rapidly, while global energy demand is rising sharply. As a consequence, diversification of energy sources is of great necessity, and renewables can play an important role in this. Solar, wind, and other types of renewable energy have the potential to alleviate the increasing scarcity, to decentralize the production of energy, and to diversify energy supply (Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015).

Secondly, renewables are key to ensuring worldwide energy access. The challenge of energy access is related to the 1.1 billion people who do not have access to electricity and to the 2.8 billion people who continue to rely on biomass, coal, and kerosene for cooking (OECD/IEA 2017). Not only does this deprive this large part of the human population from economic modernization, it also poses urgent health threats and environmental degradation risks (Dubash and Florini Reference Dubash and Florini2011). This demonstrates the urgency to tackle the widespread and persistent lack of access to modern energy services, which is predominantly the case in rural areas in the developing world. Switching to renewables does not only reduce the indoor air pollution and improve the population’s health, it is also highly suitable for small-scale and decentralized deployment, which is particularly important to address energy access (Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015).

Thirdly, an increased uptake contributes to tackling the negative environmental externalities that are associated with today’s energy systems, and the first and foremost issue related to energy is climate change. Other urgent environmental issues are air pollution, acid rain, contamination of marine environment, nuclear meltdowns, collapsed coal mines, natural gas explosions, dam breaches, and so forth (Dubash and Florini Reference Dubash and Florini2011; Florini and Sovacool Reference Florini and Sovacool2011; and Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). This makes the imperative to substitute fossil fuels and further diversify the energy mix even stronger, and renewables have the potential to do so. However, an increased uptake has its own environmental risks. For example, the cultivation of biofuel crops is associated with soil degradation and deforestation; the construction of hydropower dams with disruption of local fish stocks; the use of nuclear energy with the danger of toxic substances; and the production of solar and wind energy with the displacement of food production, interventions in stability of ecosystems, and dangers to bird life (Van de Graaf Reference Van de Graaf2013; Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015).

4.3 Meso-Level Coherence

Before zooming in on institutions at the micro level, this section describes meso-level coherence for the overall subfield of renewable energy by describing its emergence, the core norm, membership, and governance functions.

4.3.1 Emergence of the Institutional Complex on Renewable Energy

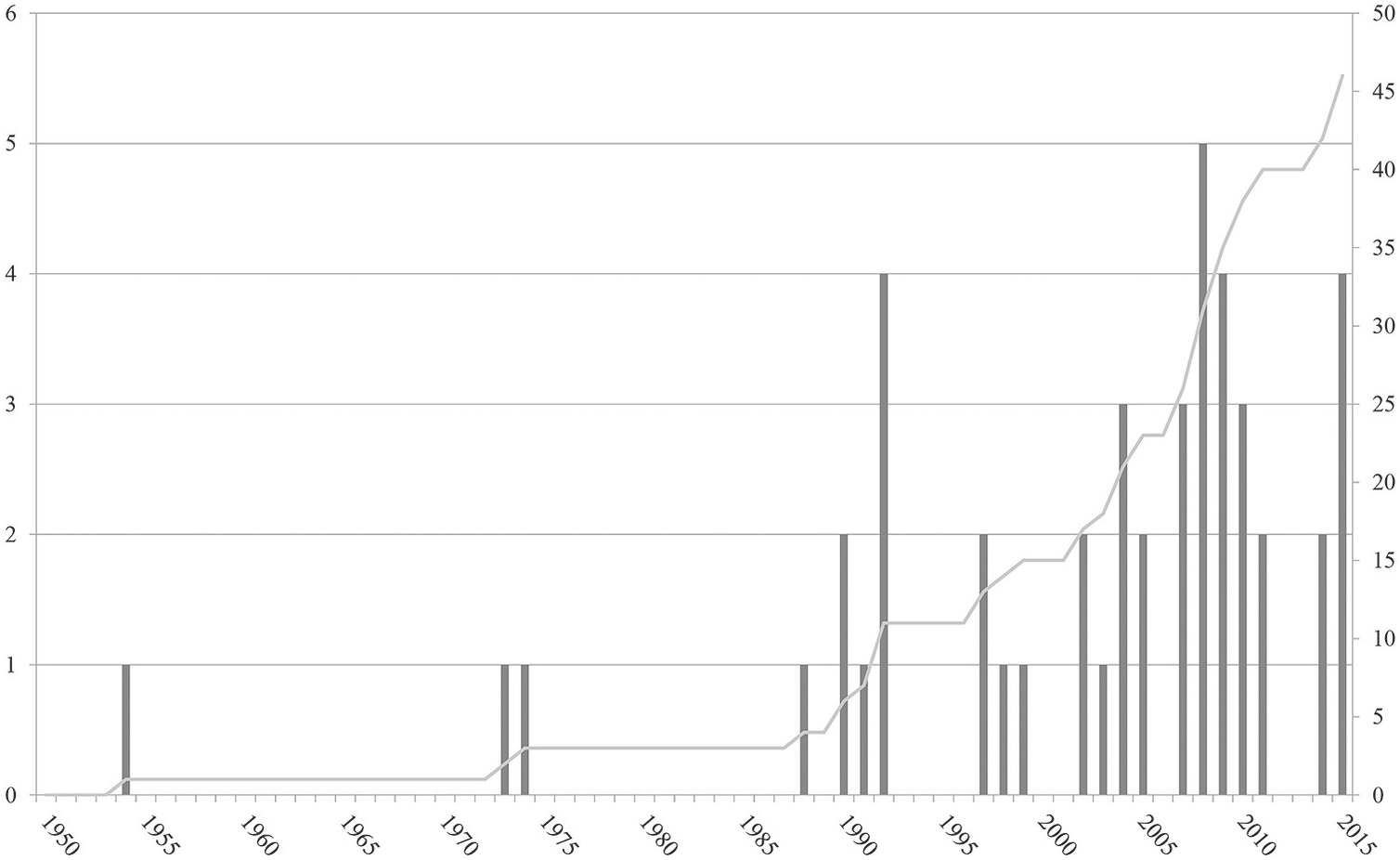

The timeline in Figure 4.1 illustrates the emergence of the institutional complex for renewable energy. As of January 2017, the institutional complex consists of forty-six institutions with different constitutive characteristics. Even though first global environmental concerns were already raised in the 1970s, and the dependence on fossil fuels was already questioned in the Brandt Report (1980), it took until the early 1990s for interest in renewable energy to grow significantly.

Figure 4.1 Starting years of renewable energy institutions from 1950 to 2015 (Author’s data).

Institutions that were established prior thereto mostly include intergovernmental cooperation efforts that were initially shaped by energy security concerns as a consequence of the oil crises in the 1970s. For example, the International Energy Agency (IEA), which initially focused on fossil sources of energy, slowly but surely widened its portfolio and extended its analyses to renewable energy (Van de Graaf Reference Van de Graaf2012; Heubaum and Biermann Reference Heubaum and Biermann2015). The emergence of institutions from the early 1990s appears to be linked to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted in 1992, followed by the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. As an illustration, the same year the UNFCCC was adopted the Global Sustainability Electricity Partnership (GSEP) was established to decarbonize the world through sustainable electrification (GSEP 2018), and similar to the Kyoto Protocol, the CarbonNeutral Protocol (CNP) was set up in 1997 to stimulate carbon reductions, for example through renewable energy certificates (CNP 2018).

However, it took until the turn of the millennium for institutions to exclusively focus on renewable energy. In 2001 the topic was for the first time discussed at the UN’s high political level, at the Ninth Session of the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen et al. Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, Jollands and Staudt2012), although no substantial agreement was reached (Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). Instead, intergovernmental institutions started to emerge outside the UN system. For example, IRENA was established in 2009. It serves as a principal forum for transboundary cooperation and provides a repository of policy, technology, resource, and financial knowledge (IRENA 2018b). That same year, the Clean Energy Ministerial (CEM) was initiated, bringing together ministers with responsibility for clean energy, to promote policies and programmes, and share knowledge and best practices (CEM 2018).

A decade later, in 2015, a growing consensus at the UN level on the strong link between energy and poverty eradication eventually led to the inclusion of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 in Agenda 2030 to ‘ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all’ (United Nations 2015, 19). More importantly, SDG 7 included target 7.2 that commits countries to, ‘by 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix’ (United Nations 2015, 19). Along with the Paris Agreement and its target to keep global temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius, SDG 7 at least marks the emergence of universal objective for global (renewable) energy governance.

In parallel to this development, a somewhat smaller expansion of institutions took place. In 2011, for instance, the Low-Emissions Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS_GP) was established to facilitate learning, technical cooperation, and information exchange supporting low emission development strategies (LEDS_GP 2018). Furthermore, the Africa Renewable Energy Initiative (AREI) was initiated in 2015 to accelerate and harness the African continent’s renewable energy potential (AREI 2018). While these two institutions focus primarily on the deployment of renewables to expand energy access, other institutions focus specifically on emissions reductions. For instance, RE100, established in 2014, brings together influential businesses to collectively promote the compelling business case for renewables (RE100 2018). Likewise, the Low Carbon Technology Partnerships initiative (LCTPI) was set up that same year to unite energy and technology companies to scale up renewables (LCTPi 2018). Finally, several other institutions exclusively target solar energy, including the Global Solar Council (GSC) and Global Solar Alliance (GSA).

In sum, the institutional complex for renewable energy comprises a multitude of institutions established within different contexts and with different institutional characteristics. The following subsections will further elaborate on some of these institutional characteristics and the variation across them.

4.3.2 The Core Norm of Renewable Energy

The Paris Agreement and the inclusion of SDG 7 as part of Agenda 2030 arguably constitute the major institutional incentive to ensure access to sustainable energy for all. More specifically, target 7.2 of SDG 7 sets the objective to substantially increase the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix by 2030 (United Nations 2015). Altogether, these institutional targets speak to the three critical challenges for global (renewable) energy governance: energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability. In sum, the core norm for the renewable energy subfield can be described as: to substantially increase the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix, in order to ensure access to and availability of clean energy for all. The normative coherence of the renewable energy subfield depends on the degree to which this core norm is shared or disputed across institutions.

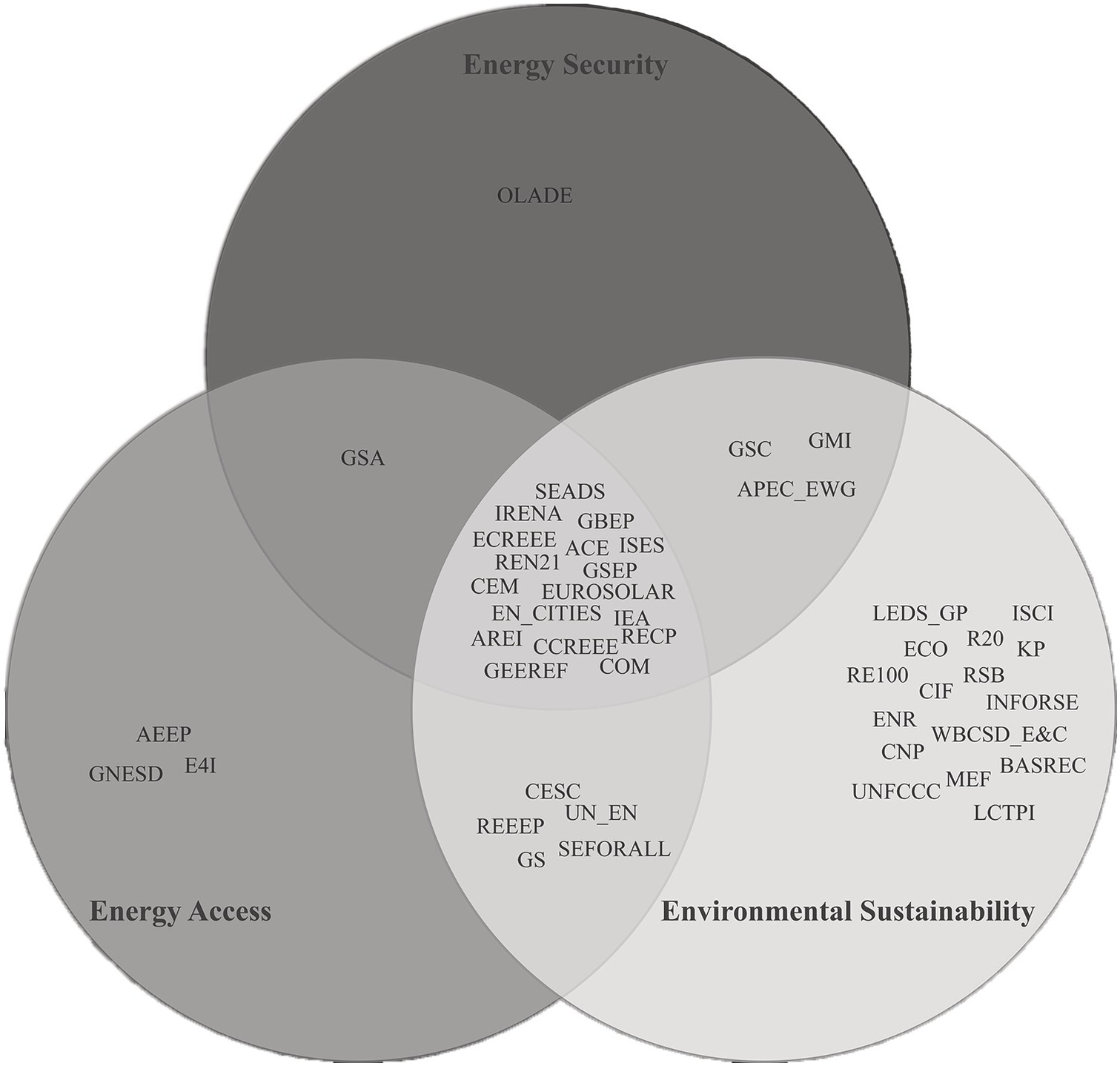

A closer inspection of the institutions’ web pages and mission statements shows that, for one-third of the institutions (17 out of 46), this core norm applies literally. These are mostly public institutions, for instance IRENA and CEM, but also three private institutions, including GSEP, EUROSOLAR, and the International Solar Energy Society (ISES), as well as two multi-stakeholder partnerships, the Global Bioenergy Partnership (GBEP) and REN21. This implies that the majority of institutions interpret the core norm more selectively, by prioritising either one or two of the main objectives, i.e. energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability, rather than approaching them in an integrated manner.

Sixteen institutions put environmental sustainability first, and interpret the core norm as to substantially increase the share of renewables to mitigate environmental externalities, most urgently the effects on the global climate. More specifically, seven of these institutions explicitly refer to the norms and targets set by the UNFCCC and its Kyoto Protocol. For instance, the LCTPI Rescale programme aims to scale up renewables and calls for action to ‘stay below 2°C of global warming’ (LCTPi 2018). Most of the institutions with a focus on environmental sustainability are public, such as Regions 20 (R20), which supports subnational governments to develop low-carbon infrastructure projects, and the Climate Investment Fund (CIF), which provides investment programmes to scale up renewable energy in low-income countries (R20 2018; CIF 2018). In addition, there are several private institutions, such as RE100 and CNP, and multi-stakeholder partnerships, namely the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), LEDS_GP, and LCTPI.

Five institutions adhere to the core norm to substantially increase the share of renewables to expand access to clean energy sources, for the purpose of improving energy access as well as mitigating climate change. These include two public institutions, namely UN Energy (UN_EN) and the Clean Energy Solutions Centre (CESC), one private institution, the Gold Standard (GS), and two multi-stakeholder partnerships, namely REEEP and SEforALL. Finally, the remaining eight institutions target either energy security, energy access, or both, or energy security and environmental sustainability simultaneously.

Figure 4.2 provides an overview of the institutions according to the core norm they predominantly adhere to. Altogether, and allowing overlaps, forty-one institutions prioritize climate change mitigation, twenty-seven addressing energy access and twenty-two energy security policy objectives. In other words, the uptake of renewables is predominantly linked to mitigating climate change, while particularly the potential of renewables to address energy security concerns is less institutionalized.

Figure 4.2 Distribution of renewable energy institutions according to their interpretation of the core norm (Author’s data).

As a consequence of these diversified priorities, there is much room for trade-offs and potential conflicts. Institutions prioritising energy security and access may, in addition to renewables, turn to the more affordable energy sources that might have a negative impact on the environment (Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015).Footnote 3 Additionally, expanding energy access implies increased energy demand, which in turn puts those institutions under pressure that seek to ensure energy security and environmental sustainability (Newell et al. Reference Newell, Phillips and Mulvaney2011). On top of this, the subfield lacks a clear definition of what constitutes a renewable source of energy, resulting in frequent controversies on bioenergy, hydropower, and nuclear energy (e.g. Elliott Reference Elliott2000; Frey et al. Reference Frey and Linke2002; Adamantiades and Kessides Reference Ademantiades and Kessides2009).Footnote 4 While solar and wind are widely acknowledged as renewable energy sources within the renewable energy subfield, twenty-five institutions include bioenergy, seventeen (small-scale) hydropower, and three nuclear power.

These diverging views have entailed conflicts of interests and competition over resources, visibility, and media attention across institutions targeting these different energy sources.Footnote 5 As long as the potential of renewable energy to address energy security is not fully institutionalized, and as long as there is no consensus on what constitutes a renewable energy source, full substitution of fossil fuels by renewables, particularly in industrialized countries, may remain unattainable.

4.3.3 Membership

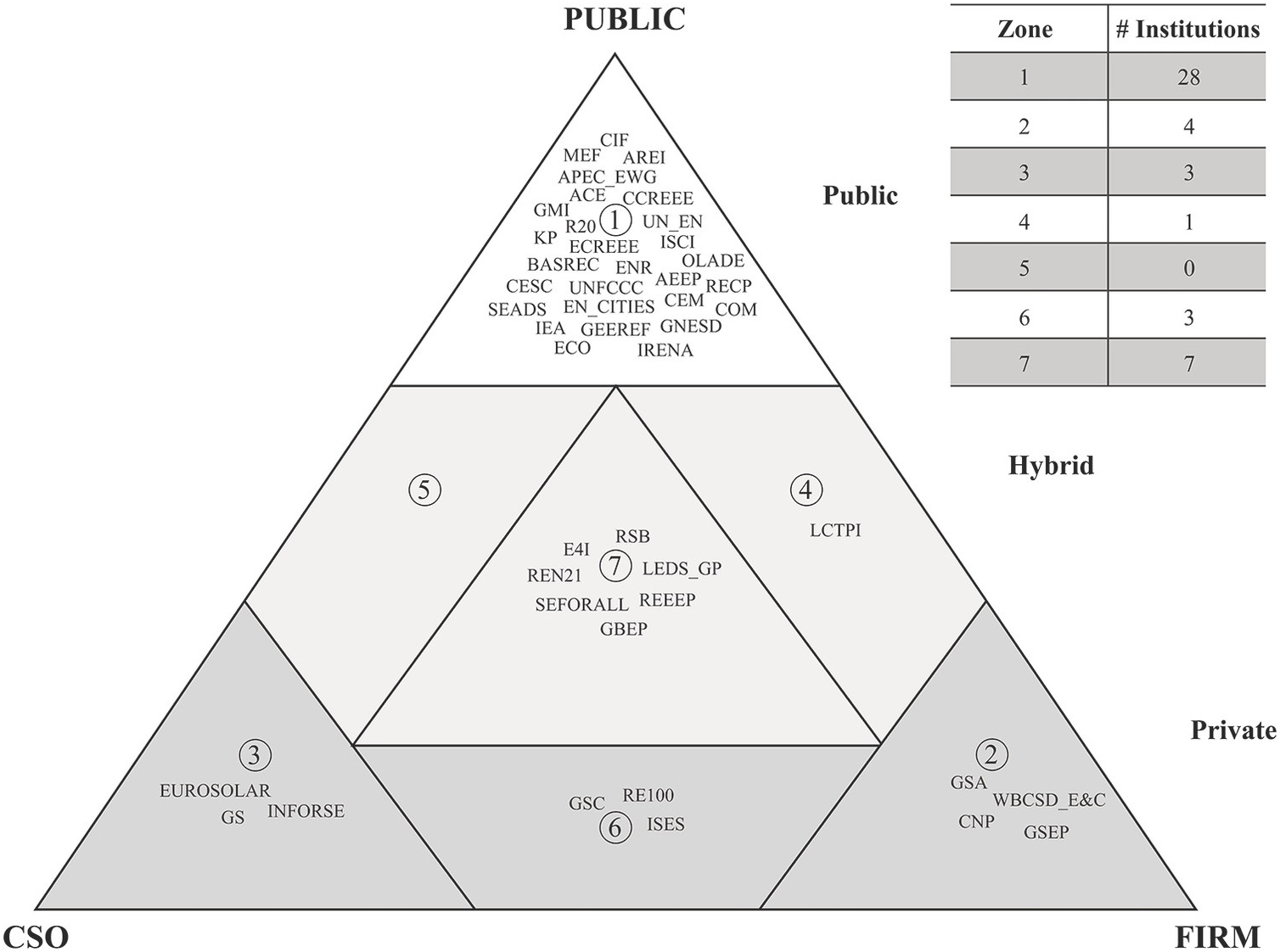

The governance triangle introduced in Chapter 3 distinguishes different types of institutions and actors that are involved in promoting the uptake of renewables globally. Figure 4.3 additionally summarizes the respective figures in a table.

Figure 4.3 Distribution institutions per zone in the governance triangle (Author’s data; see also Chapter 3).

The largest share of renewable energy institutions (28) are public. These include international organizations, such as IRENA and the IEA, as well as regional alliances, such as the Latin American Energy Organization (OLADE), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Energy Working Group (APEC_EWG), the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) Centre for Energy, and the Baltic Sea Region Energy Cooperation (BASREC). Besides these intergovernmental efforts, a number of institutions unite cities and regions in their search for appropriate strategies toward an energy transition, such as the International Solar Cities Initiative (ISCI), Energy Cities (EN_CITIES), the Covenant of Mayors (COM), and R20. While the influence of these different institutions is limited to their respective members, several other public institutions aim at assisting developing countries in increasing their share of renewables. Such institutions include, for example, the Africa-European Union Energy Partnership (AEEP) and the Global Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fund (GEEREF).

In addition to public institutions, there are ten private institutions, of which four exclusively bring together firms, industry associations, and investors. One of these is the Energy and Climate Cluster of the World Business Council on Sustainable Development (WBCSD_E&C), which unites companies from different sectors to scale up climate and renewable energy solutions globally (WBCSD 2018). In addition, there are three institutions that exclusively include nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other organizations representing civil society. These include the Gold Standard (GS), set up by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and two other NGOs, which provides a standard for climate and development projects under the UNFCCC Clean Development Mechanism (Gold Standard 2018). Furthermore, three institutions include firms, industry associations, and investors, as well as NGOs and other civil society actors, e.g. GSC and ISES.

Finally, there are eight hybrid institutions, or multi-stakeholder partnerships, which represent collaborations across societal sectors. The LCPTI is the only institution restricting its membership to public actors and firms, industry associations, and investors, while the other seven bring together all three main types of actors. Three out of these seven partnerships have been selected for further analysis in Section 4.4 on micro-level coherence: REEEP, which develops financing mechanisms to strengthen markets for clean energy in low- and middle-income countries; REN21, which connects stakeholders to facilitate knowledge exchange and policy development toward a transition to renewable energy; and SEforALL, which marshals evidence, benchmarks progress, and connects stakeholders toward achieving SDG 7 and the Paris Agreement.

While the majority of renewable energy institutions are public, private and multi-stakeholder institutions have started to play a significant role in promoting a worldwide uptake of renewable energy. In other words, there is a wide variety of actors involved, ranging from governments, international organizations, cities, and subnational authorities, to companies, financial institutions, and not-for-profit organizations. Mapping and understanding these variations is an important step toward assessing not only the coherence but also the effectiveness of the institutional complex of this subfield, since collaborations between these actors are considered key for a successful global governance of renewables (e.g. Sovacool Reference Sovacool2013).

4.3.4 Governance Functions

Renewable energy institutions perform different governance functions, which can be distinguished as setting ‘standards and commitments’, ‘operational’ activities, sharing ‘information and networking’, and ‘financing’ (see Chapter 2). Ideally, all of these governance functions are performed in a complementary manner, in accordance to the core norm, and without functional gaps or duplications.

The largest share of institutions in the sample (17 out of 46) governs renewable energy through ‘information and networking’, in combination with ‘operational’ activities. This implies that most institutions combine evaluation activities, as well as collecting and publishing information, with pilot projects, technical assistance, and capacity building. For example, Energy for Impact (E4I) assists local businesses and project developers in East and West Africa to expand energy access and publishes reports on related topics (E4I 2018). In addition, fifteen institutions exclusively govern through ‘information and networking’. A well-known example is IRENA as an international organization, which claims to serve as a centre of excellence, and a repository of knowledge (IRENA 2018b). This said, several multi-stakeholder partnerships also fulfil such a role, for instance REN21, which connects key stakeholders to facilitate knowledge exchange (REN21 2018c).

Furthermore, there are eight institutions that set ‘standards and commitments’, and more specifically develop rule-making processes, mandatory or voluntary commitments, or schemes for implementation and enforcement. This governance function is not merely reserved for public institutions, since various private and multi-stakeholder institutions provide certifications and standards to which different actors can voluntarily commit. For instance, whereas the Kyoto Protocol sets binding emission-reduction targets (United Nations 1998), the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB) sets principles and criteria to help operators, brand owners, and investors to identify and manage sustainability issues (RSB 2018). Finally, five institutions are involved in ‘financing’ to promote a global uptake of renewables, for instance through funding projects or developing aid programmes. These solely include public institutions, with one exception: REEEP, which ‘invests in clean energy markets in developing countries to reduce CO2 emissions and build prosperity’ (REEEP 2018b).

Summarizing this and the previous subsection, Table 4.1 provides an overview of the individual renewable energy institutions based on their governance functions and membership. Altogether, there is not a clear division of labour in terms of governance functions across the public, private, and hybrid institutions in the renewable energy subfield. Yet, while private and hybrid institutions play a role in all governance functions, the distribution of institutions in Table 4.1 clearly conveys the dominance of public institutions. Moreover, the table shows that there is a certain profusion of information-sharing and networking opportunities, while standards and commitments, and financing mechanisms, are limited to a few institutions. This suggests that, within the renewable energy subfield, soft measures prevail over hard ones.

Table 4.1 Overview of governance functions across different types of institutions (public, hybrid, private) for renewable energy (Author’s data).

| Public | Hybrid | Private | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standards & Commitments | CoM, KP, UNFCCC | RSB, SEforALL | CNP, GS, RE100 |

| Operational | BASREC | ||

| Information & Networking | IRENA, ISCI, MEF, ACE, APEC_EWG, ECO, EnR, SEADS, CESC | LCTPi, REN21, LEDS_GP | GSA, INFORSE, ISES |

| Financing | CIF, GEEREF | REEEP | |

| Standards & Commitments; Operational | |||

| Operational; Information & Networking | CEM, GMI, R20, AEEP, CCREEE, ECREEE, EN_CITIES, GNESD, IEA, OLADE, UN_EN | GBEP, E4I | GSEP, WBCSD_EC, EUROSOLAR, GSC |

| Information & Networking; Financing | RECP | ||

| Standards & Commitments; Information & Networking | |||

| Standards & Commitments; Financing | |||

| Operational; Financing | AREI |

4.3.5 Summary: Coherence at the Meso Level

The renewable energy subfield is institutionally complex in various ways. It includes a high number of institutions with different constitutive characteristics, covers several sources of energy and distinctive technologies, and targets no less than three critical challenges. The question remains, however, whether this plurality of institutions and objectives affects the normative, functional, and membership-related coherence in this subfield.

Altogether, this meso-level coherence, i.e. the level of coherence in the subfield as a whole, can be determined as low to medium, based on three conclusions. First, while there exists a core norm to substantially increase the share of renewables, the majority of institutions have diverging views on which objectives to prioritize. Most of these focus on promoting renewables for the purpose of mitigating climate change, or, to a lesser extent, to expand energy access, while a minority of institutions targets the potential of renewable energy to ensure energy security. As a consequence of this divergence, there is much room for trade-offs, controversies, and potential conflicts among institutions and actors across them, suggesting that normative coherence is low.

Second, the renewable energy subfield is currently dominated by public institutions, including international organizations as well as regional and subnational institutions. At the same time, the number of private institutions and multi-stakeholder partnerships has been steadily growing. The range of actors involved in the sample of this study thus increasingly stretches from public to private, implying medium membership-based coherence.

Third, all governance functions are covered by one or more institutions: most govern renewables through information-sharing and networking, and a fair share of institutions are involved in operational activities. By contrast, standards and commitments are mostly set in the form of voluntary standards and certification schemes, and financing schemes are provided by only a few institutions. In other words, there appears to be a profusion of informal activities at the expense of other important governance functions, which suggests medium functional coherence.

4.4 Micro-Level Coherence

As explained in Chapter 2, the assessments of the subfields do not stop at looking at the core norms, membership, and governance functions across the subfields as a whole. Additionally, the case studies in this volume scrutinize relations between individual institutions, i.e. at the micro-level. Whereas previous studies mostly focus on dyadic relationships between intergovernmental institutions (e.g. Charnovitz Reference Charnovitz, Aldy, Ashton, Baron, Bodansky, Charnovitz, Diringer and Heller2003; Oberthür and Gehring Reference Oberthür and Gehring2006b; Zelli and van Asselt Reference Zelli, van Asselt, Biermann, Pattberg and Zelli2010), this study analyzes a plethora of interconnections among different types of institutions. This allows for a much more encompassing assessment of an entire subfield, especially one so densely populated as renewable energy.

The subfield comprises no less than forty-six institutions, and three specific ones were selected for the in-depth analysis presented in this chapter. The following subsections describe the institutions under scrutiny, and determine micro-level coherence based on core norm, membership, and governance functions, and more importantly, by identifying mechanisms of interaction among the selected institutions.

4.4.1 Institutions under Scrutiny

Even though the majority of renewable energy institutions are public, private and multi-stakeholder institutions play an important role in governing renewables. This is particularly true for multi-stakeholder partnerships, which bring together public and private actors to collectively contribute to a public policy goal. Such partnerships generally emerge as a response to a lack of intergovernmental cooperation (Szulecki et al. Reference Szulecki, Pattberg and Biermann2011, 713). As national policy-making continues to dominate when it comes to energy issues, international energy governance is weakly developed, and especially so for renewable energy. Furthermore, cooperation between public and private actors is considered of great importance for increasing the share of renewables in the global energy mix (Sovacool Reference Sovacool2013). Whereas previous literature focused predominantly on international organizations for energy (e.g. Colgan et al. Reference Colgan, Keohane and Van de Graaf2012; Leal-Arcas and Filis Reference Leal-Arcas and Filis2013; Wilson Reference Wilson2015), a shift toward multi-stakeholder partnerships can provide novel insights on the interactional dynamics within the overall institutional complex for renewable energy.

The Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP) was one of the first multi-stakeholder partnerships on energy-related issues. Led by the British government, a group of regulators, businesses, and NGOs announced REEEP in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg (Florini and Sovacool Reference Florini and Sovacool2009; Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). Two years later the partnership was formally established as an international NGO based in Vienna. By investing in clean markets and targeting small- and medium-sized enterprises, REEEP aims to accelerate market-based deployment of renewable energy and energy-efficient systems in low- and middle-income countries (REEEP 2018b). The partnership relies on donors, which include governments, multilateral and international organizations, NGOs, and foundations. More than 350 members currently back up REEEP, including businesses, NGOs, national governments, research institutes, and many other entities. The partnership is governed by a Governing Board and an Advisory Board and is steered by an international team with more than twenty staff members and consultants. REEEP is seen as an important multi-stakeholder partnership with a clear purpose, significant output, and strong institutional formality (Pattberg et al. Reference Pattberg, Szulecki, Chan, Mert and Vollmer2009; Szulecki et al. Reference Szulecki, Pattberg and Biermann2011; Sovacool and Van de Graaf Reference Sovacool and Van de Graaf2018).

Besides REEEP, the Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century (REN21) forms an important coalition of different stakeholders to advance renewable energy policy. The German government initiated REN21 at the International Conference for Renewable Energies in 2004 in Bonn, after which it was formally launched in Copenhagen in June 2005 (REN21 2005; Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). The partnership brings together different stakeholders to facilitate knowledge exchange, policy development, and joint action toward a rapid global transition to renewable energy (REN21 2018c). Its existence depends on grants offered by governments, international organizations, and other donors, and by the end of 2017, REN21 counted sixty-four members, including industry associations, international organizations, NGOs, national governments, and research entities. The partnership is governed by its Bureau, General Assembly, and Steering Committee and has a small secretariat housed at the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in Paris. It is considered as an important advocacy network and global governor for renewable energy (Szulecki et al. Reference Szulecki, Pattberg and Biermann2011; Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015).

A more recently established multi-stakeholder partnership is Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL). It was initially launched as a UN initiative by former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon in 2011, and thereafter formalized as a non-profit quasi-international organization (Röhrkasten Reference Röhrkasten2015). While SEforALL inherited close ties to various UN agencies, it is now open to different stakeholders including governments, businesses, financiers, development banks, communities, and others. SEforALL’s mission is threefold: to ensure universal access to modern energy services; to double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency; and to double the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix (SEforALL 2018a). The partnership relies on donor contributions mostly coming from national governments, and in 2017 SEforALL counted more than eighty partners. These can be distinguished among funding partners, delivery partners (partners that commit to contribute quantifiable results and to report on progress), proud partners (partners that support SEforALL’s objectives, and use the name and platform to amplify meaningful work), and those participating in SEforALL’s regional and thematic hubs, and accelerators (SEforALL 2018b). The partnership is governed by an Administrative Board and a Funder’s Council, which guide SEforALL’s Global Team that is headquartered in Vienna and partly operating in Washington, DC. With this, SEforALL has a unique standing in the institutional complex, since it is an important multi-stakeholder partnership and major UN initiative at the same time (Röhrkasten and Westphal Reference Röhrkasten and Westphal2013).

4.4.2 Interlinkages

The three selected multi-stakeholder partnerships show differences as well as commonalities with regard to their institutional features.

First, the interpretations of the core norm for renewable energy among the three multi-stakeholder partnerships largely overlap. Particularly the partnerships REEEP and SEforALL commonly adhere to a core norm strongly influenced by targets set by the UNFCCC regime and SDG 7: to substantially increase the share of renewables for universal energy access and to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius. For example, REEEP repeatedly stresses the importance to connect its goals, targets, and metrics to the Paris Agreement (REEEP 2016a), and celebrates the inclusion of SDG 7 as a validation of REEEP’s work over the years to expand energy access (REEEP 2016a, 11). Similarly, SEforALL’s objectives include to ensure universal access to energy, double the global rate of energy efficiency, and double the share of renewables, which were formulated in the run-up to SDG 7. In addition, SEforALL reiterates that actions to achieve these objectives should be in line with the 2 degrees target agreed upon in the Paris Agreement (SEforALL 2018c). By contrast, REN21 takes on a broader approach to the core norm. REN21’s flagship publication, the Renewable Energy Global Status Report (GSR) 2018, acknowledges that scaling up renewables is crucial for limiting temperature rise below 2 degrees and for meeting the aspirations of SDG 7 (REN21 2018b). However, the partnership additionally takes into consideration the policy objective to boost national energy security (REN21 2018b).

Second, the membership directories of the three partnerships partly overlap. For instance, REEEP and REN21 share sixteen members. These include international organizations, such as the European Commission and the UNEP, and national governments such as Brazil, Germany, and the United Kingdom. In addition, REEEP and REN21 share various NGOs as members, e.g. the WWF and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). As SEforALL is essentially a partnership between the UN and the World Bank, there are no shared members with REEEP and REN21. However, some of the funding and delivery partners of SEforALL are members to REEEP (9), including respectively Austria, the European Commission, and Germany, as well as Johnson Control, UNEP, and the UN Foundation (SEforALL 2018b). Similarly, a set of funding and delivery partners are members to REN21 (6), including respectively Germany, the European Commission, Norway, and the United Kingdom, as well as the Global Association for Off-grid Solar Energy Industry (GOGLA) and UNEP (SEforALL 2018b). Among approximately 500 members spread across the three partnerships, there are only five actors all three have in common: the European Commission, UNEP, Germany, Norway, and the United Kingdom.

Third, when it comes to governance functions, the selected partnerships do not overlap, but rather complement each other. However, it is important to note that the three partnerships were also selected according to their variations in governance functions. Whereas REEEP develops and provides financing mechanisms to advance market readiness for clean energy services in low- and middle-countries (financing) (REEEP 2018b), REN21 connects different stakeholders to facilitate knowledge exchange toward a rapid transition to renewable energy (information and networking) (REN21 2018c). Finally, SEforALL connects leadership to mobilize action on SDG 7 specifically (standards and commitments) (SEforALL 2018c). Consequently, the three partnerships also target different entities; while SEforALL speaks to government leaders and REN21 to policy makers more broadly, REEEP targets small- and medium-sized enterprises.

4.4.3 Mechanisms

Institutional interactions can be broadly understood as situations in which the policy processes, knowledge, norms, or functions of two or more institutions are connected, and affect the development, performance, and impact of these institutions (Oberthür and Gehring Reference Oberthür and Gehring2006a; Zelli et al. Reference Zelli, Gupta, van Asselt, Biermann and Pattberg2012). Hence, in addition to drawing parallels based on core norm, membership, and governance function, it is key to examine the underlying interaction mechanisms between and beyond the selected partnerships. The following subsections distinguish and describe these as cognitive, normative, and behavioural (see Chapter 2; Stokke Reference Stokke2001; Oberthür and Gehring Reference Oberthür and Gehring2006a).

4.4.3.1 Cognitive

A cognitive interaction is driven by the power of knowledge and persuasion, and can be seen as cross-institutional learning (Stokke Reference Stokke2001; Oberthür and Gehring Reference Oberthür and Gehring2006a). In other words, a cognitive interaction can be determined when knowledge and information are exchanged, or certain practices and methodologies are transferred from one to the other institution. As there is a large share of institutions that govern renewable energy through information and networking, there is presumably a high degree of cognitive interaction across the institutional complex.

For REEEP, various instances of cognitive interactions were found. First, REEEP applies a framework developed by the World Bank in 2015 for SEforALL to define the concept and measures of energy access (World Bank 2015; REEEP 2018a). Second, REEEP’s regionally focused report on Powering India is informed by the IEA’s India World Energy Outlook (WEO) 2015, and REEEP’s report supporting a transition to inclusive green economies in African countries is influenced by IRENA’s Africa 2030 report (REEEP 2016b, 2017). Vice versa, REEEP’s publications have informed SEforALL and IRENA. For instance, the ‘Making the Case’ report published by REEEP influenced the Water-Energy-Food Nexus High Impact Opportunity (HIO) set up by SEforALL (REEEP 2015). The SEforALL HIOs serve as platforms that bring together stakeholders working on initiatives for the purpose of highly relevant topics related to clean energy, such as mini-grids and sustainable bioenergy. Additionally, REEEP’s publication ‘Making the Case’ contributed to IRENA’s report on ‘Renewable Energy in the Water, Energy and Food Nexus’ (REEEP 2015).

Cognitive interactions are found in larger numbers for REN21, since it is this institution’s primary role to share information and set up networking opportunities. It is especially the work of IRENA and the IEA that is regularly cited in REN21’s flagship GSRs (e.g. REN21 2017a; REN21 2018b). For instance, REN21’s latest GSR features 85 pages of endnotes including no less than 386 references to the IEA’s World Energy Outlooks, statistical reports, regional market analyses, and energy and CO2 reports, and 161 references to IRENA’s calculations and thematic reports (REN21 2018b). Similarly, REN21’s regional status reports, such as those focused on the East African Community and the regions of the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), are influenced by SEforALL’s data and information (REN21 2016a; REN21 2017b).

Besides, many more regionally focused and energy access-oriented institutions inform REN21’s regional reports, for instance the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (ECREEE), the Africa-EU Renewable Energy Cooperation Program (RECP), CIF, and E4I. Vice versa, the information REN21 shares through its GSRs is widely acknowledged,Footnote 6 and regularly shared at key events. For example, a preview of GSR 2015 was presented at the IRENA Council that same year, GSR 2016 was launched at CEM 7 in San Francisco, and the Global Futures Report of 2017 was introduced at the 2017 SEforALL Forum (REN21 2018a).

Finally, SEforALL shows similar cognitive interactions, although to a lesser extent. Besides the SEforALL HIO being informed by REEEP, the statistics, data, and country profiles of the IEA and IRENA feed into SEforALL’s Heat Maps. These inform the international community about which regions should be prioritized to close the energy access gap (SEforALL 2018b). Similarly, knowledge of ECREEE, AREI, CIF, WBCSD, and the Global Network on Energy for Sustainable Development (GNESD) has been included in SEforALL’s publication on the state of electricity access worldwide (SEforALL 2017).

4.4.3.2 Normative

The normative type of interaction (or: interaction through commitment) occurs when the commitments, norms, and principles upheld by one institution confirm or contradict those of other institutions (Stokke Reference Stokke2001; Oberthür and Gehring Reference Oberthür and Gehring2006a). On the one hand, a low degree of normative interaction can be expected for the entire institutional complex, as the majority of institutions interpret the core norm more selectively by prioritizing either one or two of the core objectives, i.e. energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability. On the other hand, Section 4.4.2 has shown that the selected partnerships are rather consentient in this regard, thus the normative interactions between REEEP, REN21, and SEforALL are considerable.

It is an enormous task to carefully compare the commitments, norms, and principles of REEEP, REN21, and SEforALL with those of all other institutions for renewable energy. However, some overlaps are expected based on the above broad evaluation of the institutions’ core norm (see Section 4.3.2). First and foremost, all three partnerships show strong normative interaction with the UNFCCC regime. As described earlier, REEEP and REN21 as well as SEforALL stress the importance of aligning their commitments, norms, and principles with the 2 degrees target set by the Paris Agreement under the UNFCCC regime. In addition, the commitments, norms, and principles of REEEP and SEforALL necessarily overlap with those institutions similarly prioritizing renewable energy for environmental sustainability and energy access, including CESC, UN Energy, and the Gold Standard (GS). Likewise, REN21’s commitments, norms, and principles presumably overlap with such institutions that are similarly inclusive toward energy security objectives, such as CEM, IRENA, and AREI.

4.4.3.3 Behavioural

A behavioural interaction refers to situations in which the actions undertaken by one institution, or members thereof, are supportive or disruptive for the performance of other institutions (Stokke Reference Stokke2001; Oberthür and Gehring Reference Oberthür and Gehring2006a). For instance, if an institution aims to expand access to energy services in rural areas by providing clean cooking appliances, these activities inherently support actions undertaken by institutions to foster emission reductions. In contrast, carbon offsetting programmes developed by an institution may undermine the efforts of institutions aiming at 100 per cent renewable energy. Thus, behavioural interactions can be driven by matching objectives (Gehring and Oberthür Reference Gehring and Oberthür2009), but also include, for instance, shaming, pressure, brand management, or monitoring each other’s performances (see Chapter 2). For the scope of this study, it would lead too far to measure the actual impact of behaviours and activities, so the following analysis suffices with distinguishing and illustrating major behavioural interactions.

It is REEEP’s main objective to advance clean energy services in low- and middle-income countries. Similarly, it is SEforALL’s priority to secure affordable and reliable clean energy for all by 2030. Thus, synergistic behavioural interactions of REEEP and SEforALL most likely occur with institutions with matching objectives at the intersection of energy access and environmental sustainability. These include UN Energy, Gold Standard (GS), and CESC (see Section 4.3.2). The synergies are supposedly strong: first, since the membership directories of these institutions only partly overlap, so that the matching objectives apply to a wider range of actors, second, as these institutions pursue these objectives through different means of governance, i.e. governance functions, complementary to those of REEEP and SEforALL.

In addition, behavioural interactions through monitoring and potentially influencing the performance of other institutions take place between REEEP and SEforALL on the one hand, and the UNFCCC, IRENA, and CEM on the other. First, REEEP visits and actively participates in IRENA’s General Assemblies, the yearly SEforALL Forum, and the UNFCCC COPs.Footnote 7 Second, SEforALL similarly performs sustainable energy diplomacy at the General Assemblies of IRENA, the UNFCCC COPs, and at the Clean Energy Ministerials (CEM) (SEforALL 2018b). Moreover, SEforALL is heavily involved in the UNFCCC process, particularly through Rachel Kyte, CEO of SEforALL and Special Representative of the UN secretary-general, and through organizing Energy Days jointly with IRENA at COP21 and 22, and presumably future COPs (SEforALL 2018d).

As mentioned earlier, it is REN21’s mission to ensure a global transition to renewable energy, to limit temperature rise below 2 degrees, to meet the targets set by SDG 7, and to boost energy security. Hence, synergistic behavioural interactions of REN21 are expected with the sixteen remaining institutions with matching objectives at the intersection of energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability (see Section 4.3.2). Similar to the interactions of REEEP and SEforALL with other institutions, these interactions of REN21 likely yield considerable benefits for both sides, since they expand the range of actors to which these objectives apply and cover complementary governance functions.

In addition, REN21 monitors and potentially influences the performance of the UNFCCC, IEA, IRENA, and SEforALL. The partnership actively participates in the UNFCCC COPs. For instance, in the run-up to COP21 in Paris, REN21 joined forces with the Covenant of Mayors (COM) to set up the Paris Process on Mobility and Climate (PPMC), and organized a series of events on ‘re-energising the future’ together with IRENA (REN21 2015). Also at the following COPs in Marrakech and Bonn, REN21 hosted and participated in several renewable energy events. On top of that, REN21 regularly attends IRENA’s General Assemblies, and SEforALL’s yearly Forum, and is a member to the IEA’s Renewables Industry Advisory Board and IRENA’s Coalition for Action (IRENA 2018c; REN21 2015, 2016b).

4.4.4 Summary: Coherence at the Micro Level

While having in common that they are key governing institutions for renewable energy, the three selected multi-stakeholder partnerships are different in a variety of ways. Whereas REEEP is backed up by more than 350 members, REN21 and SEforALL ‘only’ have 64 and 86 members, respectively. In addition, while SEforALL speaks to government leaders and REN21 to policy makers more broadly, REEEP targets small- and medium-sized enterprises. Finally, REN21 provides policy-relevant information to support a global transition toward renewables, whereas SEforALL connects leadership to mobilize action on SDG 7, and REEEP mobilizes funding to accelerate market-based deployment of renewables.

In addition to these more obvious differences, a closer analysis of the institutional features and interaction mechanisms helped determine further aspects of micro-level coherence. First, the three institutions largely share their interpretations of the core norm, and the governance functions they perform are complementary, whereas the membership directories show little overlap. In other words, the normative, functional, and membership-based coherence and complementarity across the selected institutions is high.

Second, there is an abundance of cognitive interactions between the selected institutions and beyond, which substantiate the dominance of information and networking activities within the renewable energy subfield. In addition, there are considerable normative and behavioural interactions, resulting in various synergies while, at the same time, clustering different sets of institutions around certain priorities. The interaction mechanisms therefore appear to contribute to a functional imbalance and normative divergence in the subfield as a whole. In summary, despite the fact that the institutional features between the selected institutions are highly coherent, micro-level coherence as a whole should rather be qualified as medium.

4.5 Micro-Level Management

Finally, this section zooms in on deliberate attempts to manage institutional interactions among the renewable energy institutions analyzed in the previous section. These are deliberate attempts that seek to improve institutional interaction and its consequences, so as to prevent or strengthen the influence of one institution on the performance of another (Stokke Reference Stokke2001; Oberthür Reference Oberthür2009). Typical examples are the provision of guiding principles by an overarching institution, joint coordination of activities across institutions, or unilateral management by individual institutions, for the purpose of more efficient goal-attainment (Oberthür Reference Oberthür2009, 375–376). Such management attempts may lead to stronger coherence in terms of institutional features, for instance increased convergence among interpretations of the core norm, or novel interaction mechanisms for improved exchange processes.

First, the UNFCCC regime and Agenda 2030 come forward as important overarching frameworks for the three selected partnerships. As shown in Section 4.4.2, REEEP, REN21, and SEforALL ensure that their activities match the 2 degrees target of the Paris Agreement and SDG 7. For the subfield in general, these overarching goals provide ‘international agreement’, or at least a high degree of consensus, to globally phase out fossil fuels and foster a transition toward renewables.Footnote 8 This said, besides the three partnerships ‘only’ thirteen other institutions explicitly link their activities to the UNFCCC and SDG 7. This suggests that this overarching framework has not yet fully made its way to all renewable energy institutions.

Second, three examples were found of how interactions have been managed jointly by the three partnerships put under scrutiny here. First, REEEP and REN21 collectively operate reegle.info, which is a publicly recognized information portal on renewables, energy efficiency, and climate change.Footnote 9 The portal provides country energy profiles, energy statistics and research, and a directory of relevant stakeholders (REEEP 2018c). Second, REEEP worked with IRENA to create and launch the Renewables Tagger in 2016, which is a specialized version of the Climate Tagger and automatically scans and sorts data and documents holding renewable energy content to support knowledge-driven organizations to streamline their information (Climate Tagger 2018). Third, REN21, IEA, and IRENA have recently partnered up and published a report together on ‘Renewable Energy Policies in a Time of Transition’ (IRENA, OECD/IEA, and REN21 2018).

Finally, REN21 and SEforALL unilaterally manage institutional interactions with third institutions. First, REN21 and its flagship GSR, more specifically, facilitate numerous cognitive interactions.Footnote 10 All members to REN21 can contribute to the publication, and various institutions provide authors, contributors, and reviewers, such as IRENA and the IEA (REN21 2017a; REN21 2018b). Second, SEforALL provides an important overarching platform for various institutional interactions, particularly through its thematic and regional hubs and accelerators.Footnote 11 For instance, IRENA hosts the SEforALL thematic hub on renewable energy; REN21, CESC, and ECREEE take part in SEforALL’s People-Centred Accelerator; and OLADE is an important player in SEforALL’s regional hub for Latin America and the Caribbean. On top of that, SEforALL’s Global Tracking Framework reports of 2015 and 2017, which measured progress on SDG 7, were coordinated by the IEA (World Bank and IEA/OECD 2015; World Bank and OECD/IEA 2017).

In sum, the renewable energy subfield is characterized by managed relationships, which, most significantly, provide an overarching normative framework and address cognitive interactions – and therewith, the potential overflow of information in the renewable energy subfield.

4.6 Conclusions

A global uptake of renewable energy is of paramount importance for a sustainable energy future, and while the share in the global energy mix is increasing, the growth rate is not sufficient to reach the targets set by SDG 7 in Agenda 2030 (United Nations 2018). Hence, effective global governance continues to play an important role in promoting renewables. As Chapter 3 has shown, global renewable energy governance is characterized by considerable institutional complexity. However, it is yet unclear whether this complexity significantly qualifies the institutional complex’s impact on the global energy transition. To this end, this chapter scrutinized coherence and management within the renewable energy subfield, examining institutional features at the meso level, and interaction mechanisms and management attempts at the micro level.

The analysis of the subfield, comprising forty-six institutions, shed light on various important connections across institutions and their properties. First, while one-third of renewable energy institutions share the core norm to increase the proportion of renewables for energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability, the majority of institutions interpret the core norm more selectively and prioritize either one or two of these objectives. Second, the subfield is dominated by public institutions, complemented by various private institutions and multi-stakeholder partnerships. Third, whereas most institutions facilitate information exchange and networking and, to some extent, implement projects on the ground, a significantly smaller set of institutions develops standards and commitments and financing mechanisms. Hence, the renewable energy subfield is characterized by diversified priorities – with a wide variety of institutions and actors, and with governance functions unevenly performed. The degree of meso-level coherence is therefore low to medium.

The selected multi-stakeholder partnerships, REEEP, REN21, and SEforALL, provided more detailed insights on interactional specifics at the micro-level. While these partnerships largely share the core norm for renewable energy, their membership directories hardly overlap, and governance functions are mostly complementary. Furthermore, cognitive interaction is the predominant mechanism involving the three partnerships put under scrutiny, notwithstanding the relevance of certain normative and behavioural interactions. Since these interaction mechanisms seem to aggravate the normative divergence and functional imbalance in the subfield, micro-level coherence can be determined as medium.

Besides interaction mechanisms, various management attempts were found to steer institutional interactions and foster synergies across renewable energy institutions. These mostly provide an overarching normative framework and manage the potential overflow of information within the subfield. Hence, this chapter concludes that, with a medium degree of coherence and management mechanisms in place, the renewable energy subfield is largely characterized by coordination (see Table 2.1, Chapter 2). However, such a densely populated subfield dealing with several critical energy challenges may require more than ad-hoc coordination to iron out controversies, trade-offs, and potential conflicts.

For the subfield to move toward a stronger division of labour, i.e. deliberate and continuous sharing of governance functions and norms for complementary membership (see Chapter 2), the following measures are recommended. First, the role of renewable energy to address energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability in an integrated manner needs to be fully institutionalized. A reframing of the global energy challenge and the role of renewables may contribute to such a development (Sanderink Reference Sanderink2019), as well as an expansion of membership of institutions toward those actors that are concerned with energy security. Second, the subfield would benefit from a track record or clearinghouse of the activities performed by existing renewable energy institutions, so that duplication and conflictive impacts can be resolved or prevented. Finally, it is necessary for institutions to strive for more cognitive alignment and some common understanding when it comes to defining renewable sources of energy. These three measures may require one coordinating institution, with IRENA being the likely choice: it advocates for a widespread adoption of renewables for energy security, energy access, and environmental sustainability; is closest to universal membership of all institutions in the subfield; and already positions itself as a principle platform for cooperation and repository of expertise (IRENA 2018b). Chapter 8 substantiates these policy recommendations in further detail.

Finally, this chapter gives rise to new questions that open important research opportunities. For example, how does the level of coherence and management relate to the effectiveness and legitimacy of individual institutions and the institutional complex for renewable energy as a whole? Or, what recommendations can be provided to specific public, civil society, or business actors that are trying to navigate the institutional complex? While this chapter provided a novel contribution on questions of coherence and management in renewable energy governance, these further questions will be revisited in Chapters 7 and 8.

5.1 Introduction

There is increasing recognition that fossil fuel subsidy reform (FFSR) can contribute to a host of environmental, social, and economic objectives, and thereby contribute to achieving both the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the goals of the Paris Agreement on climate change (e.g. Jakob et al. Reference Jakob, Chen, Fuss, Marxen and Edenhofer2015; Jewell et al. Reference Jewell, McCollum, Emmerling, Bertram, Gernaat, Krey, Paroussos, Berger, Fragkiadakis, Keppo, Saadi, Tavoni, van Vuuren, Vinichenko and Riahi2018; UNEP 2018). However, at several hundred billion dollars a year (OECD 2018), fossil fuel subsidies persist in both developed and developing economies.

While past research has sought to address this puzzle through the lens of domestic politics – pointing to challenges to reform such as popular opposition, vested interests, interest groups, path dependency, and capacity and data gaps (e.g. Victor Reference Victor2009; Inchauste and Victor Reference Inchauste and Victor2017) – international cooperation can also play an important role in promoting, or impeding, FFSR (Smith and Urpelainen Reference Smith and Urpelainen2017; Skovgaard and van Asselt Reference Skovgaard, van Asselt, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). For instance, while international institutions can adopt new rules, catalyze international commitments, enhance states’ accountability, and facilitate information-sharing and capacity-building, there is also a risk that they will struggle to move beyond rhetoric, promote weak, vague, or otherwise inadequate norms, or be perceived to favour certain approaches over others. Where more than one international institution is active at the same time, the door is open for cooperation, as well as competition and conflict between different institutions. This raises questions regarding the institutional coherence of international FFSR governance (see also Chapter 2).

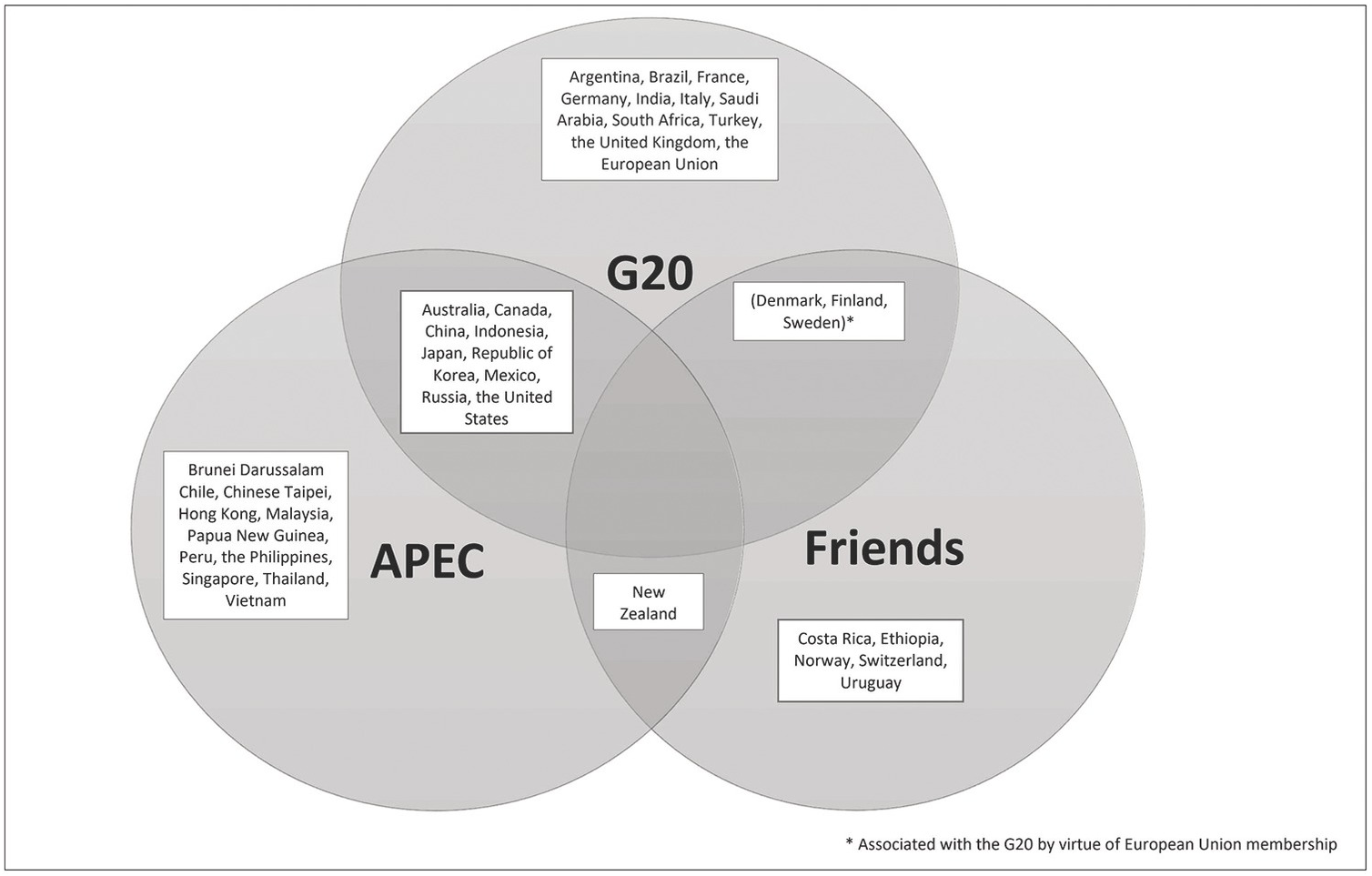

In this chapter, we consider how various international institutions are approaching FFSR governance. First, we briefly introduce the rationale for FFSR (Section 5.2). Next, we discuss the international FFSR governance architecture, with a view to analyzing institutional coherence at the meso level (Section 5.3). This includes the possible emergence of a core norm of FFSR, membership distribution, and the governance functions carried out by the various international institutions active in this area. To further evaluate the degree of coherence in this field, we zoom in on the meso level. Concretely, we examine a subset of three international clubs whose FFSR activities are among the most prominent globally: the Group of 20 (G20), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform. We first introduce the FFSR activities being undertaken by each of these three institutions, and then consider the interlinkages between these activities, as well as efforts to manage them (Sections 5.4–5.5). We conclude by considering implications of our findings for the future management of FFSR governance and the complexity thereof (Section 5.6).

5.2 Fossil Fuel Subsidies: The Rationales for Reform

Fossil fuel subsidies are a form of government support that benefits the producers or consumers of coal, oil, and gas. Both developed and developing countries subsidize fossil fuels: subsidies for consumers are more commonplace in developing countries, while those for producers are found across the board (Bast et al. Reference Bast, Doukas, Pickard, van der Burg and Whitley2015). Such assistance can come in many guises; some more direct than others. Common types of subsidies include direct transfers of funds; the setting of prices above or below market rates; exceptions or reductions on taxes; favourable loans, loan guarantees, or insurance rates; and preferential government procurement. Support can also be provided in-kind, such as when a government builds infrastructure for the primary or exclusive use of a coal company.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Energy Agency (IEA), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have all published estimates of government support to fossil fuel use and consumption. These numbers vary, depending on what valuation method is used; which countries and regions are covered; fluctuations over time; and which definition of a ‘subsidy’ is being used. However, even by the more conservative OECD and IEA estimates, global fossil fuel subsidies totalled between US $373 and 617 billion per year between 2012 and 2015 (OECD 2018). The IMF’s approach, which incorporates the non-priced externalities of fossil fuel production and consumption such as air pollution, traffic congestion, and climate change, suggests the public costs lie much higher: in the range of US $5.3 trillion in 2015 (Coady et al. Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and Shang2017).

Unsurprisingly, the IMF’s broad ‘post-tax’ interpretation of what constitutes a fossil fuel subsidy has proved controversial. Yet the Fund’s approach does help to illustrate the broader societal costs of fossil fuels. Moreover, regardless of the definition used, fossil fuel subsidies are associated with significant economic, social, and environmental impacts. Even excluding non-priced externalities, fossil fuel subsidies can represent a major burden on the public purse, taking up as much as 35 per cent of the public budget in some countries (El-Katiri and Fattouh Reference El-Katiri and Fattouh2015). They thereby reduce the investments available for key development sectors such as health and education (Merrill and Chung Reference Merrill and Chung2015), representing an important opportunity cost for developing countries in particular. Moreover, while fossil fuel subsidies are often defended as being ‘pro-poor’, the evidence suggests that such measures tend to be highly regressive, and, perversely, generally benefit those who consume the most energy in society, or powerful interest groups (Arze del Granado and Coady Reference Arze del Granado and Coady2012).

But perhaps the most urgent rationale for phasing out fossil fuel subsidies lies in their environmental impact. These subsidies artificially enhance the competitiveness of fossil fuels, potentially locking in unsustainable fossil fuel infrastructure for decades (Asmelash Reference Asmelash2016). Indeed, it has been estimated that more than a third of carbon emissions between 1980 and 2010 were driven by fossil fuel subsidies (Stefanski Reference Stefanski2014). According to the 2018 Emissions Gap Report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), phasing out fossil fuel subsidies worldwide could reduce global carbon emissions by up to 10 per cent (UNEP 2018). Government support to fossil fuels also diverts investment from areas such as energy efficiency and renewable energy, while their reinvestment in these areas could bring about important climate change mitigation benefits (Merrill et al. Reference Merrill, Toft Christensen and Sanchez2016).

Notwithstanding the adverse fiscal, socioeconomic, and environmental effects of fossil fuel subsidies, decades of experience with fossil fuel subsidy reform in various countries attest to the political challenges. While some countries, such as India, Indonesia, and Mexico, have made some progress in reforming subsidies, other countries, such as Nigeria, have struggled to implement or sustain reforms. Reforms have usually been linked to macro-economic factors such as falling fossil fuel prices (Benes et al. Reference Benes, Cheon, Urpelainen and Yang2015) or financial crises, but in many cases domestic political factors, such as the role of special interest groups, a country’s institutional and governance capacity, and the political system, play a crucial role in making FFSR a success (Skovgaard and van Asselt Reference Skovgaard, van Asselt, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018).

The importance of macro-economic and domestic political factors in hindering or driving FFSR may suggest that there is no or only a limited role for international cooperation in steering reform. However, as the next section shows, international governance can help drive (or hinder) domestic reform.

5.3 Meso-Level Coherence

5.3.1 Emergence of the FFSR Institutional Complex

As fiscal instruments of energy policy that can have numerous social, economic, and environmental effects, it is not surprising that fossil fuel subsidies are governed by a range of institutions from respective domains, such as energy, trade, and sustainable development (Van de Graaf and van Asselt Reference Van de Graaf and van Asselt2017). However, until well into the previous decade, there were hardly any international institutions focusing specifically on the problems posed by fossil fuel subsidies, or options for their reform.

This changed in 2009, a watershed moment for the international politics of FFSR. Meeting in Pittsburgh in September, G20 leaders made the first international commitment to address fossil fuel subsidies (G20 2009). This commitment was closely followed by a similar pledge by the 21 APEC economies (APEC 2009). Then-US President Barack Obama is widely credited with orchestrating the G20 pledge as he sought to shape his administration’s climate legacy, with the economic crisis offering a further window of opportunity to promote new approaches to financial governance (Van de Graaf and Blondeel Reference Van de Graaf, Blondeel, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018).

Over the subsequent decade, a range of additional institutions has become active in this field. These include various international organizations such as the OECD, IEA, IMF, and World Bank; additional minilateral coalitions such as the Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform (Friends); and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as the Global Subsidies Initiative. The profile of FFSR has further been raised through two further developments: a reference to the need to ‘rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies’ in SDG target 12.c (UN 2015); and the recent adoption, by twelve members of the World Trade Organization (WTO), of a Ministerial Statement that highlights the need to take this agenda forward in the international trade sphere (IISD 2017).

5.3.2 The Core Norm of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

The starting point of any analysis of a core norm of FFSR is the aforementioned G20 commitment, made at the Group’s third leaders’ summit in Pittsburgh in September 2009. In their statement, leaders recognized that inefficient fossil fuel subsidies encourage wasteful consumption, distort markets, impede investment in clean energy sources, and undermine efforts to deal with the threat of climate change (G20 2009, preamble). As such, they committed to ‘[r]ationalize and phase out over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption’ (G20 2009, paragraph 29). As mentioned in Section 5.3.1, ministers of APEC adopted a similar pledge later that year (APEC 2009).

While we take this formulation as the general core norm for this chapter, the precise content of the norm of FFSR remains contested and invites different interpretations. First, as mentioned in Section 5.2, there is no universal definition of a ‘fossil fuel subsidy’, and indeed, different organizations have historically approached this question in various ways (see also Chapter 8). It should be mentioned, however, that a common conception of a fossil fuel subsidy may be increasingly within reach, in particular as official guidance for their measurement has been released in the context of the SDG process (UNEP et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the G20 and APEC commitments leave important qualifiers such as ‘inefficient’ and ‘wasteful consumption’ undefined. This has given countries considerable leeway to adopt their own interpretations of their international FFSR commitments (Asmelash Reference Asmelash2016; Aldy Reference Aldy2017). As a consequence, countries such as Japan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom have been able to claim they have no fossil fuel subsidies at all (Van de Graaf and Blondeel Reference Van de Graaf, Blondeel, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018). Another issue that remains unclear is by when fossil fuel subsidies need to be phased out. Although a range of stakeholders, including leading investors and insurers (Reuters Reference Reuters2017), have called for a phase-out by 2020, and the G7 adopted a date of 2025, the G20 and APEC commitments do not have a clear timeline (with the G20’s reference to the ‘medium-term’ adding limited guidance).

Despite the textual ambiguity of these initial pledges, the understanding that at least a subset of fossil fuel subsidies ought to be reformed has gained significant global traction over the past decade, including through a reference to FFSR in the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN 2015, SDG target 12.c). The European Union has also adopted its own pledge to phase out harmful fossil fuel subsidies by 2020. Indeed, as noted by Rive (Reference Rive, Skovgaard and van Asselt2018, 164), the G20 and APEC’s initial pledges have been instrumental in ‘a reframing of a conception of fossil fuel subsidies as a legitimate government tool to enhance economic development, energy security and welfare into a normative conception that is broadly negative in fiscal and environmental terms’.

Recent developments nevertheless suggest that support for this core norm cannot necessarily be taken for granted. In 2017, the year US President Trump assumed office, G20 leaders omitted FFSR from their declaration for the first time since 2009. While the accompanying G20 Hamburg Climate and Energy Action Plan for Growth (G20 2017) includes a separate FFSR section, the document contains an overall reservation from the United States. Significantly, the 2017 APEC Leader’s Declaration also omits a reference to FFSR (APEC 2017).

5.3.3 Membership