Do you believe that “thinking like a lawyer” is an important professional skill, but by no means all that there is to being a lawyer? Do you think that being a professional calls for the development of a wide range of competencies? Do you seek to understand those competencies better? Do you think that being a professional should involve the exploration of the values, guiding principles, and well-being practices foundational to successful legal practice?Footnote 1 Are you interested in new and effective ways to build these competencies, values, and guiding principles into a law school’s curriculum? Would you like a framework for improving your own law school’s attention to these competencies, guiding principles, and values along with practical suggestions you can consider? Would you like to help better prepare students for gratifying careers that serve society well?

This book is written for law school faculty, staff, and administrators who would like to see their school more effectively help each student to understand, accept, and internalize the following:

1. Ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence at the major competencies that clients, employers, and the legal system need;

2. a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client;

3. a client-centered problem-solving approach and good judgment that ground each student’s responsibility and service to the client; and

4. well-being practices.

These four goals taken together state what it means for an individual to think, act, and feel like a lawyer. They constitute a lawyer’s professional identity. They also define the foundational learning outcomesFootnote 2 of the professional development and formation of law students movement in legal education in the United States.Footnote 3 They figure centrally in all that follows in this book. We will speak of them as the four foundational professional development and formation goals – or, for convenience and brevity, the four “PD&F” goals.

If any of these goals are important to you, this book explains how to help your students achieve them. Importantly, this book also explains how you can influence others – the faculty, staff, and administrators at your school; your students; and the legal employers your graduates serve – to adopt these goals and take steps to achieve them. We look first at the benefits from a more effective curriculum on each of the four goals.

1.1 The Benefits of a More Effective Curriculum to Foster PD&F Goal 1: Each Student’s Ownership of Continuous Professional Development toward Excellence at the Competencies That Clients, Legal Employers, and the Legal System Need

Law students, faculty, staff, and administrators want to increase the probabilities of better academic performance, bar passage, and meaningful postgraduation employment for each student. Strong empirical data show that student growth toward later stages of ownership of continuous professional development (as reflected in self-directed/self-regulated learning) enhances student academic performance,Footnote 4 and that stronger student academic performance in turn correlates with higher probabilities of bar passage.Footnote 5 Diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging initiatives aimed at helping disadvantaged studentsFootnote 6 also benefit substantially from a more effective curriculum (particularly a continuous coaching model of the kind we will analyze in Chapter 4) that fosters belonging and provides institutional support to navigate the educational environment and the job market.Footnote 7

To the extent that online learning may provide lower levels of support and guidance to students than in-person classroom education, self-directed/self-regulated learning skills characterized by student skill in planning, managing, and controlling their learning processes become even more important for student performance.Footnote 8 Data also show that legal employers and clients greatly value initiative and ownership of continuous professional development;Footnote 9 a student who can communicate evidence of later-stage development on self-directed/self-regulated learning will demonstrate strong value to potential employers.

1.2 The Benefits of a More Effective Curriculum to Foster PD&F Goal 2: Each Student’s Deep Responsibility and Service Orientation to Others, Especially the Client

Many law faculty and staff would like to see each law graduate internalize a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, particularly the client. We also know that a substantial proportion of undergraduate students in the applicant pool are seeking a career with opportunities to be helpful to others and useful to society.Footnote 10

Deep care for the client is the principal foundation for client trust in both the individual lawyer and the profession itself.Footnote 11 That deep care essentially entails a fiduciary disposition or fiduciary mindset, using “fiduciary” in the general meaning of founded on trustworthiness.Footnote 12 Each law student and new lawyer must learn to internalize a responsibility to put the client’s interests before the lawyer’s self-interest.Footnote 13 As Professor Greg Sisk emphasizes in a recent treatise on legal ethics: “When the lawyer protects confidential information and exercises loyal and independent judgment uninfected by conflicting interests or the lawyer’s own self-interest, the lawyer’s responsibilities are distinctly fiduciary in nature. In these matters, the trust of the client is directly at stake.”Footnote 14

The legal profession also holds out other fiduciary mindset values and guiding principles relating to trust in each lawyer. For example, the Preamble of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct states, “[a] lawyer should strive to attain the highest level of skill, to improve the law and the legal profession, and to exemplify the legal profession’s ideals of public service.”Footnote 15 It declares, “a lawyer should seek improvement of the law, access to the legal system, the administration of justice and the quality of the service rendered by the legal profession” and emphasizes the following:

A lawyer should be mindful of deficiencies in the administration of justice and of the fact that the poor, and sometimes persons who are not poor, cannot afford adequate legal assistance. Therefore, all lawyers should devote professional time and resources and use civic influence to ensure equal access to our system of justice for all those who because of economic or social barriers cannot afford or secure adequate legal counsel.Footnote 16

The Model Rules contemplate that a lawyer will possess very broad discretion when exercising professional judgment to fulfill responsibilities to clients, the legal system, and the quality of justice – and that the lawyer also has a personal interest in being an ethical person who makes a satisfactory living. The Preamble recognizes that “difficult ethical issues” can arise from these potentially conflicting responsibilities and interests. “Within the framework of these Rules,” the Preamble observes, “many difficult issues of professional discretion can arise. Such issues must be resolved through the exercise of sensitive professional and moral judgment guided by the basic principles underlying the Rules.”Footnote 17 The Preamble further notes, “a lawyer is also guided by personal conscience and the approbation of professional peers.”Footnote 18

The Model Rules recognize that clients also face many difficult ethical issues, and a lawyer should provide “independent professional judgment and render candid advice” to help the client think through decisions that affect others.Footnote 19 As the comments to Rule 2.1 note, “[a]dvice couched in narrow legal terms may be of little value to a client, especially where practical considerations, such as cost or effects on other people, are predominant … . It is proper for a lawyer to refer to the relevant moral and ethical considerations in giving advice.”Footnote 20 The lawyer is not imposing the lawyer’s morality on the client; rather, the “relevant moral and ethical considerations” upon which the lawyer is to draw and offer counsel – and therefore needs to comprehend – include the client’s own tradition of responsibility to others.

The foregoing implicitly defines the elements of a law student’s and lawyer’s fiduciary mindset. They call on each law student and lawyer to

1. Comply with the ethics of duty – the minimum standards of competency and ethical conduct set forth in the Rules of Professional Conduct;

2. foster in oneself and other lawyers the ethics of aspiration – the core values and guiding principles of the profession, including putting the client’s interests first;

3. develop and be guided by personal conscience – including the exercise of “sensitive professional and moral judgment” and the conduct of an “ethical person”– when deciding all the “difficult issues of professional discretion” that arise in the practice of law;

4. develop independent professional judgment, including moral and ethical considerations, to help the client think through decisions that affect others; and

5. promote a justice system that provides equal access and eliminates bias, discrimination, and racism.

Fostering each student’s development toward later stages of responsibility, service, and care for the client and the legal system has obvious benefits for students. As we discuss in Chapter 5, principle 8, research shows that students rank service to others as a significant personal objective that motivates them to pursue a career in law.Footnote 21 Supporting students in this way also contributes to the missions of many law schools and the aspirations of many faculty and staff, advancing the ideals and core values of the profession including service to the disadvantaged. As we shall see in the next section, benefits flow to clients and legal employers as well. They value client-centered lawyering and creative problem solving in the lawyer’s exercise of good independent professional judgment emphasized by the Model Rules.

1.3 The Benefits of a More Effective Curriculum to Foster PD&F Goal 3: Each Student’s Client-Centered Problem-Solving Approach and Good Independent Professional Judgment That Ground Each Student’s Responsibility and Service to the Client

Legal employers and clients want law graduates who demonstrate deep responsibility and service orientation to others, ownership over continuous professional development toward excellence, a client-centered problem-solving approach, and good independent professional judgment. Law students (prospective new lawyers) who have evidence of later-stage development of these competencies can increase their probability of meaningful employment – a major benefit to the students and their law school as well.

A growing number of empirical studies are defining the capacities and skills that clients and legal employers need in their changing markets, reaching results that substantially converge in support of the central importance of the third PD&F goal. Among the major studies are the following:

1. The 2003 Shultz/Zedeck survey, including principally University of California–Berkeley alumni, identifying lawyer effectiveness factors;Footnote 22

2. Hamilton’s 2012–14 and 2017 surveys of the competencies assessed by large firms, small firms, state attorneys general offices, county attorneys offices, and legal aid offices;Footnote 23

3. The Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System 2016 study of 24,137 lawyers’ responses to the question of what competencies are “necessary in the short term” for law graduates;Footnote 24

4. Thomson Reuters’ 2018–19 interviews and survey of law-firm professional development lawyers and hiring managers on what are the most important competencies for a successful twenty-first-century lawyer;Footnote 25

5. The Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System 2019 study on the competencies that clients want, based on a random sample of 2,232 AVVO client reviews of lawyers in the period 2007–17;Footnote 26

6. The 2019 Association of Corporate Counsel survey of 1,639 respondents who self-identified as the highest-ranking lawyer in a company;Footnote 27

7. The 2019 BTI Consulting Group’s Client Service A-Team Survey of Law Firm Client Service Performance, which includes data from 350 in-depth telephone interviews with senior in-house counsel at large organizations;Footnote 28

8. The 2020 National Conference of Bar Examiners survey of 3,153 newly licensed lawyers (up to three years of practice) and 11,693 not recently licensed lawyers asking how frequently newly licensed lawyers performed specifically listed tasks;Footnote 29

9. The 2020 Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System’s national study using fifty focus groups, asking respondents about the knowledge and skills that new lawyers used during the first year of practice;Footnote 30

10. Lisa Rohrer and Mitt Regan’s in-depth interviews with 278 law partners at larger US law firms to assess whether business concerns are eclipsing professional values in law firm practice, published in 2021;Footnote 31 and

11. The National Association for Law Placement report on a 2020 Survey of Law Firm Competency Expectations for Associate Development published in 2021 based on survey results from fifty large-firm competency models.Footnote 32

The work of leading futurists looking at the legal services market reinforces the picture. They emphasize that the competencies needed for a successful twenty-first-century lawyer include a more proactive entrepreneurial mindset to meet changing market conditions for clients and lawyers alike.Footnote 33

All of the aforementioned studies essentially asked lawyers and clients to identify the most important competencies needed to practice law. While both attorneys and clients include client-service orientation and relationship skills among the important competencies needed to represent clients, the clients emphasize these skills more heavily (including communication, attentive listening, responsiveness, understanding of the client’s context and business, and explanation of fee arrangements).Footnote 34

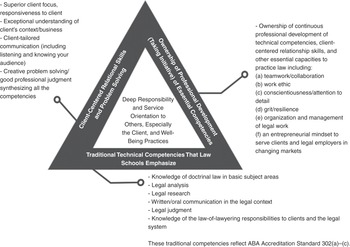

Synthesizing all these empirical studies into a useful model of the foundational competencies that clients and legal employers need can be a challenge. In a recent white paper, Thomson Reuters presents what it has titled the “Delta” model of lawyer competency. The model groups lawyer competencies into three categories, with each category represented by one of the three sides of a triangular figure. The base of the triangle represents the technical skills traditionally associated with lawyering. The upper two sides of the triangle represent “personal effectiveness factors” and “business and operations” competencies, respectively.Footnote 35 We find much to favor in the Delta model; its chosen visual form for depicting the differing yet interrelated competencies of effective lawyering strikes us as particularly effective. A model that serves the needs of legal educators does well to draw from the Delta model, but it needs important adaptations to reflect insights about professional education, the student’s formation of professional identity, and methods of competency-based education – and also to incorporate the fuller range of competencies identified by the aforementioned studies.

Building on the Delta model approach, we offer here a Foundational Competencies Model (depicted in Figure 1) that law school faculty, staff, and administrators can consider and modify to best articulate the competencies that clients and legal employers served by their school’s graduates need. Appendix A provides a summary of the empirical studies mentioned earlier that also can be useful to inform faculty and staff discussion. The model in Figure 1 reflects four principles that should inform any model developed for an individual law school:

1. The model should be based on the best available current data on the competencies that clients and legal employers need;

2. the model should be clear and understandable to a new law student and include a manageable number of competencies;

3. the model should be in the language that legal employers use, thereby helping students communicate their value to employers; and

4. the model’s foundational competencies should be translatable directly into institutional learning outcomes established by the law school.

The empirical studies also support the conclusion that the following six traditional technical competencies that law schools emphasize are necessary but not sufficient to meet client and legal employer needs in changing markets:

1. Knowledge of doctrinal law in the basic subject areas;

2. legal analysis;

3. legal research;

4. written and oral communication in the legal context;

5. legal judgment; and

6. knowledge of the law-of-lawyering responsibilities to clients and the legal system.Footnote 36

The additional competencies that the studies indicate clients and legal employers need from lawyers in changing markets include the following:

1. Superior client focus and responsiveness to the client;

2. exceptional understanding of the client’s context and business;

3. effective communication skills, including listening and knowing your audience;

4. creative problem-solving and good professional judgment in applying all of the previously noted competencies;

5. ownership over continuous professional development (taking initiative) of both the traditional technical competencies previously listed, the client relationship competencies previously listed, and the skills or habits described later;

6. teamwork and collaboration;

7. strong work ethic;

8. conscientiousness and attention to detail;

9. grit and resilience;

10. organization and management of legal work (project management); and

11. an entrepreneurial mindset to serve clients more effectively and efficiently in changing markets.

Figure 1 visually represents a Foundational Competencies Model that captures and conceptually organizes all these major competencies that clients and legal employers need. At the center of the Foundational Competencies Model – visually and conceptually – is each student’s internalization of a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client, that creates trust. That internalized commitment informs all the other competencies. The center of the model also includes well-being practices because lawyers must care for themselves to care for others.

Figure 1 Foundational Competencies Model based on empirical studies of the competencies clients and legal employers need

The center of the Foundational Competencies Model could also include a deep responsibility and service orientation to the legal system itself in terms of a commitment to improve the legal system and pro bono service for the disadvantaged. These internalized commitments are not emphasized in the empirical data on the capacities and skills that clients and legal employers want, but the law faculty and the legal profession may emphasize these commitments.

The bottom side of the model makes clear that each student and lawyer must demonstrate the basic technical legal competencies that clients and employers need. The left side of the model makes clear the foundational importance to clients and employers of each student and new lawyer demonstrating client-centered problem solving and good professional judgment in serving the client – including superior client focus and responsiveness, exceptional understanding of the client’s context and business, and communication skills including listening and knowing the audience.Footnote 37 The right side of the model makes clear the foundational importance for clients and employers of ownership of continuous professional development (taking initiative) toward excellence at the competencies needed, harnessed to an entrepreneurial mindset to serve well in rapidly changing markets for both employers and clients. Employers and clients need strong teamwork and collaboration skills, a strong work ethic, conscientiousness and attention to detail, grit and resilience, and organization and management of legal work. An entrepreneurial mindset includes constant attention to client goals and completion of work more effectively and efficiently, including making effective use of technology.

A student or new lawyer who demonstrates later-stage development of these foundational competencies will benefit clients and legal employers and has a higher probability of meaningful postgraduation employment and long-term success in a service profession like law. These outcomes benefit the student, while also benefitting the law school and its faculty, staff, and administration. The law school also can demonstrate to enrolled students – and prospective applicants – that it is helping them achieve their goals of bar passage and meaningful postgraduation employment.

1.4 The Benefits of a More Effective Curriculum to Foster PD&F Goal 4: Student Well-Being Practices

In response to increasing evidence of chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and addictive behaviors among law students and lawyers,Footnote 38 many law faculty and staff have heightened their concern about student well-being. Lawrence Krieger and Kennon Sheldon analyze a robust branch of modern positive psychology – self-determination theory (SDT) – that provides an empirical framework to understand student well-being. It also outlines the benefits to students, faculty, and staff of increasing student well-being.

What is well-being? Krieger and Sheldon treat subjective well-being in their studies as the sum of (1) life satisfaction and (2) positive affect or mood (after subtracting negative affect). They utilize established instruments on each factor. Life satisfaction includes a personal (subjective) evaluation of objective circumstances such as one’s work, home, relationships, possessions, income, and leisure opportunities. Positive and negative affects are purely subjective, straightforward experiences of “feeling good” or “feeling bad.”Footnote 39

What are the basic psychological needs that contribute to student well-being? Self-determination theory defines three basic psychological needs contributing to well-being: (1) autonomy (to feel in control of one’s own goals and behaviors), (2) competence (to feel one has the needed skills to be successful), and (3) relatedness (to experience a sense of belonging or attachment to other people).Footnote 40 Note that the first two professional development and formation goals with which we began this chapter (ownership of continuous professional development toward excellence and a deep responsibility and service orientation to others, especially the client) reflect significant aspects of SDT’s three basic psychological needs.

Autonomy is considered the most important of the three basic psychological needs since people must have a well-defined sense of self and express their core values in daily life to function in a consistent way.Footnote 41 SDT posits that there are positive outcomes for subordinates when organizational authorities support their autonomy by giving them (1) as much choice as possible, (2) a meaningful rationale to explain decisions, and (3) a sense that authorities are aware of and care about their point of view.Footnote 42 These positive outcomes include (1) higher self-determined career motivation, (2) higher well-being, and (3) higher academic performance.Footnote 43

Sheldon and Krieger’s three-year longitudinal study of students with very similar LSAT scores and undergraduate grade point averages at two law schools compared student outcomes at the law school where students perceived stronger autonomy support with outcomes at the law school where students perceived weaker autonomy support. Students at the school with stronger autonomy support had higher well-being, better academic performance on grades, more self-determined motivation to pursue their legal careers, and better performance on the bar examination.Footnote 44 Krieger and Sheldon followed up with surveys submitted from 7,865 practicing lawyers in four states.Footnote 45 The responses from practicing lawyers affirmed that autonomy, competence, and relatedness strongly predict respondents’ well-being.Footnote 46 The practicing lawyers also affirmed that autonomy support from supervisors increased their well-being and self-determined motivation.Footnote 47

In Chapter 4, we will outline how law schools can utilize coaching to provide autonomy support and help improve well-being for each student. In addition to helping students achieve their goals, faculty and staff who provide that support will help the school to achieve its goals of improved bar passage and postgraduation employment outcomes.

1.5 Realizing These Benefits at Your School

The next two chapters focus on strategic planning to realize the foregoing benefits at your school. Chapter 2 explains and stresses the importance of purposefulness in the law school’s efforts to help students to realize the four PD&F goals. The reader will find a framework for bringing that purposefulness to work in the law school. Chapter 3 explores how competency-based education can serve as a possible framework for purposeful support of students toward the four goals. That discussion will introduce the reader to important lessons that legal education can learn from the experience of medical education, which changed its accreditation requirements to require competency-based education fifteen years earlier than legal education.

Chapters 4 and 5 focus on practical implementation steps to realize the benefits we just outlined at your law school. Chapter 4 brings forward ten principles from the literature on higher education that should inform the development of any law school curriculum to foster each student’s progressive growth toward later stages of development on the four PD&F goals. Chapter 5 stays with the practical, turning attention to how interested faculty, staff, and administrators can lead their school toward more purposeful support of students and their PD&F goals. Recognizing that the various, and sometimes differing, interests of the major stakeholders of a law school influence the school’s actions, Chapter 5 presses the importance of a clear understanding of those interests. That understanding, we believe, can only be obtained by going where each major stakeholder actually is, and we illustrate how to do that. The good news is that stakeholder interests can converge on a shared interest in student progress toward the four PD&F goals. As Chapter 5 explains, bridges can be built to connect stakeholders and their interests to the law student’s realization of PD&F goals.