The networks and spaces of information exchange that fostered expansion come to life in Robert Cecil’s testimony at Walter Ralegh’s trial for treason in 1603. The jury accused Ralegh of possessing a seditious book written against the sovereignty of kings, one that had been kept from public view in the private study of the late lord treasurer William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Burghley’s son Robert, James’ secretary of state, suggested Ralegh may have stolen the book when visiting Burghley’s study to consult his cosmographical works. Ralegh often visited their residence on the Strand, Cecil acknowledged. ‘Sir Walter desired to search for some Cosmographycall descriptions of the West-Indies which he thought were in his study, and were not to be had in print, which he [Cecil] granted’.Footnote 1 Before ‘the bonds of his affection had been crackt’, Cecil admitted, he had admired Ralegh and had supported Ralegh’s ventures to North America and Guiana.Footnote 2

The first part of this chapter investigates the breadth of colonial interest among members of the elite within this interpersonal world of patronage and political alliance, tracing colonial endorsement in converging, at times competing, metropolitan circles. The chapter then turns to what colonizing projects actually meant to the elite who became involved with them. While the colonist John Smith remained on the margins of Jacobean politics, gentlemen commended his role in clearing landscapes for intervention. Prefatory verses in The generall historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Iles (1624) lauded Smith for forcing Native Americans to ‘bow unto subjection’, so that ‘brave projects’ would ‘forge a true Plantation’.Footnote 3 Governors and colonists, but also domestic benefactors, were called to ‘Spend money, [and] Bloud’ to receive God’s blessing and to facilitate territorial possession.Footnote 4 The ability to subordinate both human nature and the natural world was inherent in cultivation, suggesting that planting colonies was not a benign alternative to conquest. The transformation and restraint of nature was a painful, often destructive process, frequently deemed necessary for achieving political control.

The final section connects changing attitudes to landscapes in post-Reformation England to gentlemanly aspirations in America. For the Jacobean elite, the pursuit of a fulfilling and pleasurable civil life was deeply rooted in property and governance. Fundamental attitudes towards land underpinned the impetus to civilize. This became especially apparent from the later 1610s, as the gentry began to show a greater interest in surveying and managing plantations as the most efficient method of colonizing Bermuda and Virginia. ‘Christ hath given us’, Samuel Purchas proclaimed, ‘the Universe in an Universall tenure’.Footnote 5 In contrast to hopes for quick profit through joint-stock investment, land became critical to the elite vision of how a transatlantic polity might be sustained. Land committed gentlemen to overseeing an empire held together not only by trade, but also by the hierarchical structures of governance that accompanied traditional estate-holding.

Planting in the Age of Projection

From the 1570s to the 1630s, a distinct language of planting emerged, surpassing other tactics and models for colonization.Footnote 6 Elizabethan statesmen drew on a humanist vision of expansion that united the possibilities of exploitation with a strong strain of civic responsibility, encouraging the pursuit of Atlantic projects in Ireland and further west.Footnote 7 Seeking to advance a model of Protestant society that differentiated English colonization, at least in theory, from Spanish methods of conquest, Richard Hakluyt the younger composed his ‘Discourse of Western Planting’ for Elizabeth at the behest of Ralegh in 1584.Footnote 8 Though Elizabeth may never have read the document, the text indelibly influenced the language and rhetoric of future projects, where the English right to plant in North America was related to global competition with Spain and legitimized partly by promising to ‘civilize’ and convert its local inhabitants.Footnote 9 At the same time, the early seventeenth century saw developments in the concept of ‘improvement’, which began to apply not just to land and property, but ‘to every aspect of human and social behaviour’.Footnote 10

Proposals to convert indigenous Americans while ridding the realm of overpopulation by sending labourers to the colonies appeared repeatedly in charters, parliamentary debates, and royal proclamations, but the overall appeal and success of investment hinged on hopes of financial benefit. Schemes to find precious metals and to cultivate tobacco, iron, timber, silk, and other commodities were integral to the writings of colonial promoters from Hakluyt and Ralegh in the 1580s to gentry MPs in the 1620s. The projects by merchants including William Cockayne and Thomas Smythe that looked eastwards to Europe and Asia were matched by others centring on Virginian tobacco and Newfoundland cod by Robert Johnson, Richard Whitbourne, and Roger North. That the ‘fourth part of the world, and the greatest and wealthiest part of all the rest, should remaine a wilderness, subject … but to wilde beasts … and to savage people, which have no Christian, nor civill use of any thing’ forged a relationship between the possibilities of wealth and the need to civilize other peoples.Footnote 11

Commerce and trade heavily informed policy-makers’ reformist politics, where ‘radical transformations and controversies in ways of thinking about the universe, the natural world, and the body politic’ shaped attitudes towards private gain and common good.Footnote 12 Insofar as the voyages fit within his vision of a unified ‘Great Britain’ strengthened by industry and inhabited by faithful, conforming subjects, James was happy to affix the royal seal to Atlantic enterprises. James’ personal style of kingship made policy-making a matter of ‘patronage politics’, where the Crown and the court placed financial stakes in projects on an unprecedented level.Footnote 13 The possibilities of enriching the Crown through trade and industry attracted a king who experienced notorious difficulty convincing Parliament to subsidize Crown expenses. Though the Crown, under Elizabeth, had attempted to restrict expenditure, James inherited substantial debts even before he increased the deficit with his lavish spending.Footnote 14 Members of the Privy Council were unable to mitigate the long-term consequences that accompanied the Crown’s need to sell its lands to meet expenses. Monopolies on colonial commodities remained a consistent point of contention and opportunity in the Crown’s desperate search for sources of revenue, while Members of Parliament used the more lucrative aspects of Atlantic trade to promote industry and bargain for certain rights and privileges.

When the merchants and economic writers Gerard Malynes and Thomas Mun offered financial counsel to the Crown, and James’ treasurers sought to revise the king’s means of securing revenue, they did so with the recognition that the need to find and circulate wealth would not only benefit their and the king’s interests, but also contained consequences for the realm as a whole.Footnote 15 Speaking to the Commons on the dire state of economic affairs in 1621, Sandys showed concern that ‘if we bring [the English] so slender comfort as these poor bills, we make their discontents and dislike of their miserable fortunes reflect upon the higher powers’.Footnote 16 Members of Parliament expressed a sense of responsibility towards social welfare, and many of the men who displayed the most zeal in addressing the realm’s social ills were also those, like Sandys, who promoted colonization as a natural solution to a range of problems the English faced under James, including finding employment for the poor and pursuing manufactures. ‘O[u]r cuntrie is strangely anoyed w[i]th ydell, loose and vagrant people’, wrote the brothers Edward and Thomas Hayes in their efforts to promote colonization, but ‘the State hath wisely in p[ar]liam[en]t sought redress’.Footnote 17

Vivid accounts of colonial horrors in the early decades of English expansion can distract from the levels of enthusiasm evident in the metropolis. Jamestown offered a chronicle of miseries, from rumours of colonists eating each other during the Starving Time of 1609/10 to the ensuing martial law that imparted governors with the power to execute colonists for stealing food or fleeing to Powhatan villages. By 1624, a report from Virginia recorded 1,275 people in the colony, despite the thousands of English men and women who had migrated from England over the previous seventeen years.Footnote 18 Though 4,000 people migrated between the late 1610s and the early 1620s, the population remained reduced to a quarter of that number, with death rates in the earliest years estimated at more than 80 per cent.Footnote 19 The Virginia Company, for all its propaganda campaigns celebrating fruitful landscapes, raised a total stock of 37,000l., a ‘trifling’ sum when compared to the corporations establishing trade with India or the Levant.Footnote 20 When the state secretary George Calvert finally went to his Ferryland colony in Newfoundland in 1629 after years of painstaking preparation, he found himself unable to conform to the rhetoric of abundance that had lavished his previous letters. ‘In this part of the world, crosses and miseryes is my portion’, Calvert wrote. ‘I am so overwhelmed with troubles … I am forced to write but short and confusedly’.Footnote 21

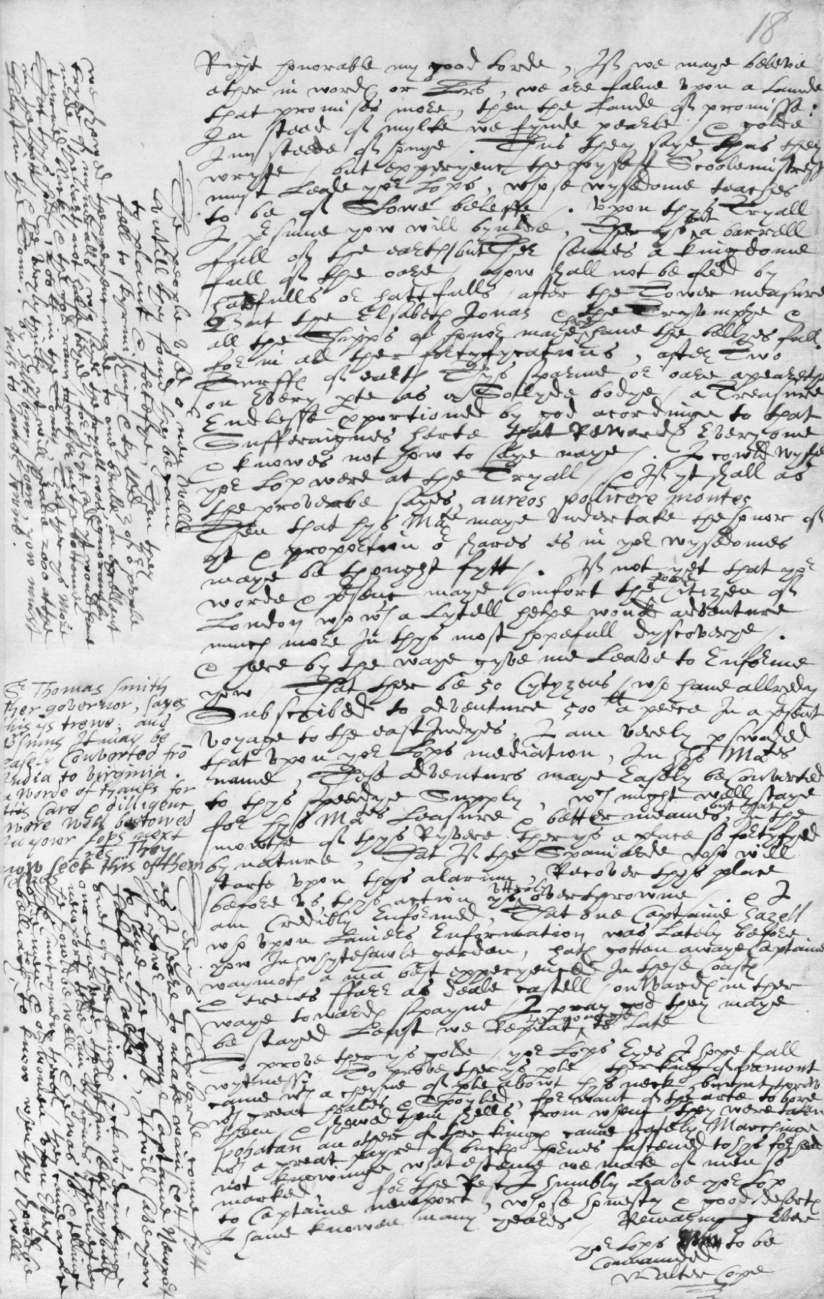

A different perspective emerges when examining colonization from within the metropolis, rather than its initial settlements. The court administrator Walter Cope, who regularly entertained the king and queen in London, wrote a letter to Cecil in 1607 that brimmed with news from Virginia, including details about pearls and Wahunsenacah/Powhatan (Figure 2). ‘When the busines [sic] of Virginia was at the highest, in that heat’, the letter writer John Chamberlain reported in 1613, ‘many gentlemen and others were drawn by perswasion and importunity of frends to under-write theyre names for adventurers’.Footnote 22 Chamberlain acknowledged that gentlemen were less willing to part with their money than they were to write their names to paper, but the ‘perswasion’ of ‘frends’ evokes a rising metropolitan fashion for subscribing to colonial projects. ‘[T]here was much suing for Patents for Plantations’, John Smith recalled of the early 1620s, and ‘much disputing concerning those divisions, as though the whole land had been to [sic] little for them’.Footnote 23 Englishmen far beyond London, complained the Somerset vicar Richard Eburne, had been so enamoured with the idea of supporting the Virginia Company, despite the risks, that they had lacked ‘the wit, not to run out by it, to their undoing’.Footnote 24

The precariousness of English settlements in the Chesapeake, Bermuda, and New England ensured these places retained a place in political debates in London. In 1620, the contentious governor of Bermuda, Nathaniel Butler, complained to his patron, Nathaniel Rich, that being governor of Bermuda had proved ‘an extreame discouragement’ because ‘every petty Companion and member of your Court and Company … upon the least false and base Intelligence fastened upon their precipitate credulitie … snarle and braule his fill at him’.Footnote 25 This invokes Chamberlain’s remark that debates about Virginia and Bermuda at Whitehall had led to public outbursts and even brawls.Footnote 26 These reports heavily suggest that the ‘snarls and brawls’, the political contests over colonization schemes, were a formative part of London policy-making, though it would be the inhabitants of the colonies who suffered most from the consequences of inconsistent policies. While colonists in Bermuda complained that ‘ther is not scarce a thought … amongst the Company [in London] of sending us any shippynge from England above once a yeare, and then [only] for our Tobacco’, policy-makers in England saw their involvement as a means of advancing the interests of the realm by actively engaging in contemporary politics and associated debates about the welfare of their civil society.Footnote 27

While James’ son, Henry, vigorously cultivated the image of a Protestant military prince, the king’s interest in colonization can admittedly appear scant. In 1609, Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, wrote to Cecil informing him of James’ interest in acquiring a flying squirrel. ‘Talkinge w[i]th the K[ing]’, Southampton wrote, ‘by chance I tould him of the Virginia squirrels w[hi]ch they say will fly … & hee, presently & very earnestly asked mee if none of them was provided for him’.Footnote 28 Southampton’s record of his discussion with James about Virginia and its fauna seemed to be an afterthought, added at the close of his letter. It was ‘by chance’ that Southampton had raised the matter, and he added that ‘I would not have trobled you w[i]th this but that you know so well how [the King] is affected to these toyes.’Footnote 29 James’ delight at the prospect of a winged rodent gives little sense that he had spoken seriously with Southampton about what else had been happening in 1609, including a campaign by members of the Virginia Company in London to stimulate colonial support through a series of print publications and sermons following the signing of the second company charter.Footnote 30

Until Cecil’s death in 1612, most letters by investors or colonial promoters were sent to Cecil rather than to James. Yet assumptions of James’ disinterest are misleading in several ways. Firstly, this indifference should not be seen as indicative of James’ reign as a whole. From 1619 in particular, the king began to take active interest in the affairs and government of the Virginia Company, as Chapter 2 demonstrates. Secondly, correspondences between Spanish ambassadors hint at James’ shrewdness. When asked by Pedro de Zuñiga about English plans at Jamestown in 1607, the king ‘answered that he was not informed as to the details of what was going on … and that he had never known that Your Majesty [Philip II] had a right to it … it was not stated in the peace treaties with him and with France that his subjects could not go [where they pleased] except the Indies’.Footnote 31 This seems less the rejoinder of a hapless monarch, and more like the response of one who knows when to feign ignorance. ‘The King said to me’, Zuñiga continued, ‘that those who went, went at their own risk, and if they were caught there, there could be no complaint if it were punished’ – a remark that may have held true for the Indies, but not for Virginia, since the king had signed dispensations for Richard Hakluyt, Robert Hunt, and numerous others to venture there in late 1606 and early 1607.Footnote 32

Ambiguous Crown interest in North and South America might be indicative of James’ reluctance to upset the shaky nature of Anglo–Spanish peace rather than actual disinterest.Footnote 33 Negotiations over territorial acquisition in the West Indies were so contentious in the 1604 Anglo–Spanish peace negotiations that the treaty ignored the issue altogether when no concession could be reached. Cecil’s refusal to concede to Spanish territorial claims in the Atlantic became vital to allowing the English to settle parts of North and South America in subsequent decades.Footnote 34 It was with immense pressure from the Spanish Crown that James sanctioned ventures led by Thomas Roe, Walter Ralegh, Roger North, William White, Charles Leigh, and Robert Harcourt, even as Spanish agents beseeched James to ‘looke carefully to the busines of not p[er]mitting such a voyage to be made’.Footnote 35 However much he valued the Anglo–Spanish peace, James did not allow English exploration in the West Indies to stop altogether.

From 1612 to 1618, while the Virginia colony struggled to find stability, many members of the gentry turned to Bermuda. Of the 117 founding investors, 5 were noblemen, 18 were knights, and 21 were MPs.Footnote 36 All but ten held shares in the Virginia Company, many of them also involved with the East India Company and voyages in search of the Northwest Passage.Footnote 37 The second Earl of Warwick and other members of the Rich family dispatched ships to send ‘negroes to dive for pearls’ and to bring back tropical plants, plantains, figs, and other ‘West Indy’ goods.Footnote 38 Merchants returned from the island with pearls, coral, ambergris, pineapples, and tobacco.Footnote 39 A chance finding of a lump of ambergris – whale secretion used for perfume – gained as much as 12,000l. for the ailing Virginia Company at a time when the same London councillors had joint oversight of Virginia and Bermuda.Footnote 40 Even before its successful planting, Silvester Jourdain wrote in 1610 that Bermuda contained ‘plenty of Haukes, and very good Tobacco’, appealing to the civil pursuits of landed gentlemen while promoting the colonization of this ‘richest, healthfullest, and pleasing land’.Footnote 41 Although the island seemed remote, Jourdain wrote, it held all the promise that the best colonies contained. By the mid-1610s, the surveyor Richard Norwood had mapped out the land divisions on the entire island. Norwood’s surveying of the landscape served to delineate property lines, but it also established relationships and obligations between the English land-holding elite and their colonial tenants.Footnote 42 Company meetings in London remained essential to the development of the island, and the strong correlation between metropolitan interest and the survival of the colony is evident in the letters colonists sent back to London in this period.Footnote 43

Countless individuals took it upon themselves to pursue various schemes at their own personal cost. William Alexander received substantial support from James and then Charles to conduct voyages to New Scotland (Nova Scotia). After his patron, Prince Henry, died, Alexander became gentleman usher to Henry’s brother Charles. He spent a prodigious 6,000l. of his own money to prepare a voyage in 1622, contributing further funds for two other attempts until Charles I conceded Nova Scotia to the French in the early 1630s. Alexander advocated intermarriage with Native Americans, believing that ‘lawfull allyances … by admitting equalitie remove contempt’.Footnote 44 His support of intermarriage was rare, though many of his other attitudes to colonial policy were representative of those shared by the English and Scottish elite. Plantations were to establish civil life for its inhabitants, ‘not to subdue but to civillize the Savages’ so that they ‘by their Posteritie may serve to many good uses’, while Europeans must not succumb to ‘naturalizing themselves where they are, [lest] they must disclaime their King and Countrey’ with their ‘affections altered’.Footnote 45 Alexander’s tract showed a clear vision of the colonies in Virginia, New England, Newfoundland, Ireland, and Bermuda as encompassing a wider, more singular project.

Failed projects also offer insight into the interworking of Jacobean political networks. Ralegh’s hopes for extracting precious metals and stones in Guiana were supported by Thomas Roe, later made a gentlemen of James’ privy council, who travelled to South America in 1611. Roe was a product of the early Jacobean Middle Temple milieu, a particularly strong site for imperial projects due to its ties to the West Country. Benchers at the Middle Temple made Francis Drake an honorary member of its society after he circumnavigated the globe in 1580. There was a ‘fervour’ in ‘this business … this most christian and Noble enterprise of plantation’, Roe wrote to his patron, Cecil, in 1607.Footnote 46 ‘[D]ivers Noblemen and Gentlemen have sent in theyr mony’, but also ‘divers attend in person, enough to performe this project’.Footnote 47 Schemes in South America, Roe believed, would bring profit to the nation and combat the dishonour of allowing Spanish ascendancy in the Atlantic, while making ‘provinciall to us a land ready to supply us with all necessary commodytyes’.Footnote 48

The creation of the short-lived Amazon Company led James to irritably profess that he ‘had never seen an enterprise so supported’ as Roger North’s plans for Guiana in the early 1620s.Footnote 49 The list of investors for the voyage exhibits a high level of engagement with the project. The Spanish ambassador at James’ court, Diego Sarmiento de Acuña, Count Gondomar, cited seven of the thirty-four privy councillors of 1620 as members of the Amazon Company, meaning 20 per cent of James’ councillors regarded the company as a useful potential arena to advance their interests and to pursue an anti-Spanish agenda.Footnote 50 George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, Ludovick Stuart, Duke of Lennox, Henry Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Rich, second Earl of Warwick, and Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, were cited as prominent supporters of this inference against Spanish colonial designs. Gondomar recognized them as ‘the foremost personages of this kingdom’.Footnote 51 The Duke of Lennox had conducted campaigns on James’ behalf in parts of Gaelic Scotland in the 1590s. Southampton was treasurer of the Virginia Company at the time. The Earl of Warwick, aggressively exploiting the opportunities colonization offered, made his kinsman Nathaniel a Somers Islands Company agent and worked closely with him in overseeing plantations.

James’ ruling elite actively pursued colonization despite, or perhaps because of, the king’s own hesitation to directly embroil the Crown in territorial disputes involving lands already claimed by the Spanish. Imprisoned on charges of treason since 1603, Ralegh pursued his advancement of English territories from the Tower. Seeking royal sanction for another voyage to Guiana, he complained to Queen Anne in 1611 that, if anything, James did not show enough desire for wealth. He had only sought, Ralegh lamented, ‘to have done him such a service as hath seildome bine p[er]formed for any king’, but James continually rejected those ‘riches wich God hath offred him, therby to take all presumption from his enemies, arising from the want of tresor, by which (after God) all states are defended’.Footnote 52 Ralegh’s letter demonstrates the way that colonial projects informed the ‘more flexible notions of public interest and the public good’ emerging from early seventeenth-century economic understandings of commonwealth, where God-given riches enabled states to declare and extend their sovereignty.Footnote 53

For the more militant supporters of colonization in the first decade of the seventeenth century, the solution to James’ desire for reconciliation with Spain was to seek patronage in the courts of Anne of Denmark at Greenwich and Somerset House, and Prince Henry at St James’ Palace. Henry promoted an interest in navigation, cosmography, and art that reflected his pro-expansionist foreign policy, adopting militant sensibilities that stood in stark contrast to his father’s iconography of divine right and compromise.Footnote 54 ‘We suffer the Spanish reputation and powre’, wrote a frustrated Roe in 1607, ‘to swell over us’.Footnote 55 Henry explicitly chose to surround himself with tutors, artists, and counsellors who shared more combative pro-Protestant policies, filling the roles of Gentlemen of the Bedchamber and Privy Chamber with men who had participated in colonial projects in various capacities. Letters from Virginia specifically addressed to the prince reported the safe arrival of the English almost immediately after the establishment of James Fort.Footnote 56

When the Jamestown governor Thomas Dale heard of Henry’s death in 1612, he lamented that the demise of his principal patron would be both his undoing and the unravelling of the entire colony.Footnote 57 It was in Henry’s court that plans for a Guiana Company and Northwest Passage expeditions took shape, and where playwrights like George Chapman wrote The memorable masque for Elizabeth and Frederick’s nuptials, a performance that featured masquers apparelled as indigenous Americans. Henry had judiciously overseen ‘the North West Passage, Virginia, Guiana, the Newfoundland, etc., to all which he gave his money as well as his goodly word’.Footnote 58 The interest Henry fostered in pursuing colonization, coupled with his contempt for Catholicism, created an environment where Protestant courtiers, gentlemen, poets, and playwrights might advance their political agendas, especially during the years of the Catholic Howard family’s ascendancy in James’ court. The prince’s widely mourned death cut short the more active, militant role that royalty held in promoting colonization, but gentlemen in Parliament and the Inns of Court stepped up to the task.

The failure to enlist James’ more overt interest in colonization motivated an anonymous petition to the queen in 1610, beseeching Anne to follow Queen Isabella of Castile’s lead by patronizing voyages to America. The petitioners asked that Anne be ‘the meanes for the furthering’ of plantation, not only to ‘augment the number of gods church, but also procure great benifitt by plenty of trade’ so that ‘his Ma[jes]t[ie]s kingdomes might be made the storehouse of all Europa’.Footnote 59 The letter emphasized the zeal of the realm’s subjects, suggesting that the king might ‘erect an order of knighthood … to the w[hi]ch our Lo[rd]: the prince of wales his Excellencie to be cheife Lo[rd] Paramount’, where ‘divers knights and esquiers of the best sort of noble descent’ would provide for ‘the planting’ of North America.Footnote 60 An American knighthood, led by Henry, would likely have appealed to the prince’s militant sensibilities, but the letter also viewed Anne as the ‘meanes’ through which colonization would occur.

The letter to Anne offers a small window into female interest in colonization. In 1617, Lady Ralegh sold her house and lands in Mitcham, Surrey, valued at 2,500l., to provide funds for her husband’s Guiana venture.Footnote 61 In 1620, the Virginia Company recorded a handful of female investors.Footnote 62 These included Elizabeth Carew, Viscountess Falkland (one share), Elizabeth Gray, Countess of Kent and Katherine West, Lady Conway (two shares each), Mary Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury (four shares), and Sarah Draper (one share).Footnote 63 Female investment in the Virginia Company suggests a tantalizing possibility that women from both middling and elite backgrounds saw investment as an opportunity to participate in fiscal-political affairs in the realm. Lucy Russell, Countess of Bedford, appeared on the patent for the governing council of the Virginia and Somers Islands Company in 1612. Her name came second only to the Earl of Southampton’s in the Bermuda charter of 1615, after the Somers Islands/Bermuda left the aegis of the Virginia Company.Footnote 64

Bedford was a patron of Michael Drayton, Roe, John Donne, and other colonial enthusiasts who navigated the orbit of Prince Henry’s court. In this light, Donne’s references to Virginia in a poem dedicated to the countess may actually reflect an interest of hers as much as his. Donne painted a charming picture of a man’s body as an American microcosm: ‘who e’er saw … That pearl, or gold, or corn in man did grow?’Footnote 65 The glow of alchemized precious metals, the sensual pearl, and abundant maize intimately brought the allure of the Chesapeake into the human frame. ‘We’ve added to the world Virginia,’ Donne wrote to a woman who may have been as enticed by effecting colonization as he was.Footnote 66

Beyond Whitehall and the royal courts, large numbers of gentry MPs supported westward colonization.Footnote 67 More than half of the Virginia Company’s 560 gentry were MPs.Footnote 68 All but three individuals on the initial Virginia charter of 1606 sat in the House of Commons, and half held some royal office, indicating policy-makers’ attempts to give political weight to North American enterprises.Footnote 69 The gentry faction of the Virginia Company led by Edwin Sandys and Southampton gained sway over the merchant faction headed by Thomas Smythe and the Earl of Warwick in 1619, and their leadership steered plantation towards a traditional gentry land-holding system governed by the common law and elected representatives.Footnote 70

Sandys, an extraordinary figure in the Jacobean Parliaments and the Virginia Company, considered overseas involvement and trade to be a key part of how the English gentry might promote the good of the realm. Sandys played on the changing nature of political roles open to gentlemen in society, particularly in peacetime. ‘What else shall become of Gentlemens younger Sons’, he asked in 1604, ‘who cannot live by Arms, when there is no wars, and Learning preferments are common to all, and mean? Nothing remains fit for them, save only [to] Merchandize’.Footnote 71 John Oglander expressed similarly: ‘It is impossible for [a] mere country gentlem[a]n ever to grow rich or raise his house. He must have some other vocation with his inheritance … If he hath no other vocation, let him get a ship and judiciously manage her’.Footnote 72 Younger sons of country gentlemen served as MPs and in minor offices of state while helping with the colonial interests of their patrons, serving as secretaries, or employing agents to trade in New England beaver furs. Concerns to prevent ‘our warlike discipline [to] decay not, and so sincke … the honor of our state and Countrey’, in the words of another MP, made involvement in overseas expansion and war in a Protestant cause a viable option for gentlemen, as when Anthony Knivet, an illegitimate son of a country knight, travelled to Brazil in the service of the explorer Thomas Cavendish.Footnote 73 The frontispiece to Richard Brathwaite’s The English gentleman (1633) aptly conveyed the role of travelling across the seas in gentlemanly participation in civil life. Brathwaite portrayed the ideal gentleman, clad in fashionable but sober dress, as well educated, moderate, and godly, standing above ‘Vocation’, who ‘fixeth his eye on a Globe, or Marine Map’.Footnote 74

Gentry interests were linked to a wider network of colonial support bolstered by the efforts of captains and churchmen. A Captain Baily frequently presented plantation schemes to the Privy Council, which he believed would empty overcrowded English prisons and allow people in the localities to partake in the evangelizing mission. He proposed that every man in England and Wales who gave a penny annually for ten years should receive the same stock-holding privileges as those who ventured 1,000l. The Privy Council noted that Baily claimed to have made his project known ‘to many thousands’, some of whom had already subscribed up to 10l. per annum, and none less than 2s 6d.Footnote 75 Four months later, the council reported to have conferred with Baily about his proposals, but ultimately decided that the sums he promised could not be realistically levied. Baily continued with his petitions, adapting his plans and confident that interest in the localities would eventually convince the king and his council of their commitment.Footnote 76 The Virginia Company lotteries also brought colonial promotion to the localities and shed light on non-elite investment in colonial schemes.Footnote 77 In 1610, ‘the Mayor and Commonality of Dover’ invested in the company, hoping to gain ‘full part of all suche landes’ or whatever might be found on them, including precious metals and pearls.Footnote 78 Stamped with the royal seal, these lottery certificates demonstrate an intersection between plantation and the parishes, between the endorsement of the Crown and the initiatives of individuals outside the aristocracy to subordinate America to English interests.

While the impressions of individuals who supported the imperial project are not always recoverable, the diary of Stephen Powle offers a glimpse into how gentlemen understood their endorsement of colonization on a personal level. Between financial reports and Latin verses, Powle included news from overseas voyages, situating these within a providential framework. ‘I delivered to Sir Thomas Smith Treasorer of the viage to Virginia the summe of fifty powndes’, Powle recorded in 1609, ‘and I am to be one of the Counsell of this expedition … The success of whitch undertakinge I referre to god allmighty’.Footnote 79 Several months later, Powle noted that the ships under Thomas Gates had departed, and he wished ‘god blesse them and guide them to his glory and our goode’.Footnote 80 Nor were Powle’s interests for Virginia alone. He also followed Roe’s plans in 1610 to command the expedition in Guiana. Southampton had invested 800l., Powle noted, and Ralegh 600l.Footnote 81 Powle contributed 20l., but his reference to ‘my sealf’ suggests a sense of collective association, in which investing made him a significant contributor. News about these ventures circulated in letter-writing networks, as in the 1611 newsletter containing reports on the settlements in Ulster, Virginia, Newfoundland, and Bermuda.Footnote 82 Competing for capital from City merchants, the newsletter stressed that while the citizens of London were ‘exceding wearye of theyre Ireyshe plantacion’, ‘[t]he state and hope of the Bermodes’ remained high.Footnote 83 The Newfoundland governor John Guy sent deerskins and wolf and fox furs ‘for [t]estymony’ of its bounty, and prepared ‘for further plantacion … wherunto all men are very forward to put in theyre moneyes, by reason this plantacion is very honest peacefull, And hopefull, And very lykely to be profytable’.Footnote 84

Savagery and Improvement in the Language of Reform

Deep-rooted convictions about land, governance, and authority underpinned the elite’s financial and political interest in colonization. While profit remained an obvious motivation for imperial pursuits, the risks involved in joint-stock investment remained high. Most investors lost rather than gained assets when the Virginia Company went bankrupt in 1624. Investing in Eastern trade or in domestic manufactures often proved more profitable. A better understanding of the relationship between plantation and civility demonstrates how, and why, gentlemen viewed ‘civilizing’ savagery as a moral imperative and a political act. The belief in their prescribed role in upholding order, and their attitudes to cultivating ‘savage’ landscapes – territories that needed to be enclosed, tilled, and continually managed – enabled gentlemen to reconcile profit and virtue while promoting the creation of a transatlantic polity.

As Paul Slack argues, ‘improvement’ in seventeenth-century England ‘became a fundamental part of the national culture, governing how the English saw themselves and the condition of the nation to which they belonged’, more so than in other European countries.Footnote 85 Plantation was both objective and method, related to the management of land and the hopes of capitalizing on natural resources. At a time when gentlemen sought to claim and enclose the lands around their estates, a lack of tillage seemed to offer a ‘reproach’ to the authority of households.Footnote 86 Land management through surveying and husbandry contributed to a landholder’s sense of civility. Copying out aphorisms by the Roman senator Cato, one Jacobean individual related multiple adages to the word ‘husbandry’ – not only maxims on labour but others on fate, caution, and spending money.Footnote 87 Far outnumbering any other words in the marginalia, associations with ‘husbandry’ suggested a sense of the word as related to personal virtue and moral responsibility as well as to the physicality of the natural environment.

The perceived rawness of America and its peoples invited interference and a sense of opportunism. William Bradford, recounting the Separatists’ first arrival on the shores of Cape Cod in 1620, described the initial encounter with the landscape in identical terms to those expressed by Londoners. It was:

a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men … the whole country, full of woods and thickets, presented a wild and savage hue. If they looked behind them, there was the mighty ocean which they had passed and was now as a main bar and gulf to separate them from all the civil parts of the world.Footnote 88

In 1613, Samuel Purchas expressed the commonplace belief that ‘savage’ peoples and landscapes were locked in a particular relationship with each other. The Algonquians ‘seeme to have learned the savage nature of the wild Beasts, of whom and with whome they live’.Footnote 89 Gentlemen associated a perceived lack of land cultivation with the lack of human culture. James granted charters to North America ‘for the inlarging of our Government, increase of Navigation and Trade, and especially for the reducing of the savage and barbarous people of those parts to the Christian faith’.Footnote 90 The Privy Council sanctioned voyages to Guiana because South America was ‘inhabited with Heathen and savage people, that have no knowledg [sic] of any Christean Religion for the salvac[i]on of their Soules, and that are not under the Gover[n]ment of any Christian Prince or state’.Footnote 91 These words emphasized that, at least formally, the Crown supported colonization primarily to introduce ‘savage’ people to the civil life, where education would impart indigenous peoples with the capacity to comprehend Christianity and divine order. Even the vim of Richard Whitbourne’s discourse on Newfoundland did not avoid the usual tropes, declaring the venture useful for industry while noting that the inhabitants, being ‘rude and savage people[,] having neither knowledge of God, nor living under any kinde of civill government’, were failing to usefully achieve settlement.Footnote 92

To implement civility, the English needed to establish a permanent presence in America, as degeneration was believed to flourish anywhere that was not continuously cultivated. Purchas’ ‘Virginia’s Verger’, appearing in Purchas his pilgrimes (1625), is in many ways a husbandry manual for state-building. Referencing Genesis 1:29 (‘Behold, I have given you every herbe bearing seede, which is upon the face of all the earth’, KJV), Purchas stated at the start of his tract that ‘we have Commission from [God] to plant’.Footnote 93 Man, created in God’s image, had been given dominion over nature. God had made Adam and Eve cultivators, and had told his chosen people that ‘ye shall be tilled and sown’ and purified as a result (Ezekiel 26:9, KJV). Referring to the lost settlers of Roanoke, Purchas evoked the quasi-mystical language of sacrifice and fertility, in which the blood of the dead colonists proclaimed an ownership of the land: ‘Their carcasses … have taken a morall immortall possession, and being dead, speake, proclaime, and cry, This our earth is truly English’.Footnote 94 Unconstrained savagery, including English assumptions of indigenous paganism, would be removed by possessing the soil and fertilizing it with English blood.

The gentlemen who invested money and time in projects were not subscribing just to the ventures themselves, in other words, but also to the ideas about savagery and authority that underpinned them. Purchas described Native Americans as possessing ‘little of Humanitie but shape, ignorant of Civilitie, of Arts, of Religion’, rendering them ‘more brutish then [sic] the beasts they hunt, more wild and unmanly then that unmanned wild Countrey, which they range rather then inhabite’.Footnote 95 Here Purchas made explicit this link between a lack of husbandry and the need for civil society, while ‘unmanly’ raised the connection between masculinity and the obligations of gentlemen to subdue the unruly. Francis Bacon criticized merchants for looking ‘ever to the present gaine’, expressing the belief that they were ill suited to establish plantations because hopes for immediate profit would always outweigh moral responsibility towards good governance.Footnote 96 The process of subjugating ‘[s]avagenesse to good manners and humaine polity’ would create a system of transatlantic rule, inspiring ‘English hearts in loyal subjection to your Royall Soveraign’.Footnote 97

Horticultural metaphors were widely used to express the necessity of subjection as an act of creating subjects. Algonquians seemed to possess ‘unnurtured grounds of reason’, wrote the colonist and minister Alexander Whitaker, that ‘may serve to encourage us’ to nurse promising seeds to fruition.Footnote 98 When the literary scholar Rebecca Bushnell set out to research gardening manuals of the sixteenth century, she found her sources to be as concerned with moral behaviour as with botany, where attitudes to land and education reflected wider concerns about the nature of authority and control.Footnote 99 ‘Ther can not be a greater or more commendable worke of a Christian prince’, wrote Arthur Chichester from Ireland in 1605, ‘then to plant cyvilytie w[i]th the trewe knowledge and service of God in the hartes of his subjectes’.Footnote 100 In Latin, cultura signified the cultivation of land, and Cicero, Ovid, and Tacitus used colere, to cultivate or tend, to denote agricultural work but also nourishing in a metaphysical sense. ‘Culture’ invariably entailed the cultivation of land or industries as well as the development of the mind, faculty, and manners. This made culture a moral imperative, for, in the words of Cicero, ‘just as a field however fertile cannot be fruitful without cultivation, neither can the soul without instruction’.Footnote 101 In the language of planting, pro-imperial gentlemen condemned savagery while simultaneously proposing a practical solution to eradicate it.

The idea of planting begins to reconcile what initially seems to be a contradiction between civilizing and violence. Anti-Spanish rhetoric in England continuously pitted Spanish conquest against the refining projects of English plantation. But although the English styled themselves as benevolent ushers of order, cultivation contained ingrained theories about the need to restrain or remove malign influences. Destruction was not antithetical but inherent to growth. ‘As seeds and roots of noisome weeds’, Robert Johnson wrote in his promotion of Virginia, unchecked English behaviour would ‘soone spring up to such corruption in all degrees as can never bee weeded out’.Footnote 102 The English believed they had a responsibility to redress savagery and to ‘manage [the Algonquians’] crooked nature to your forme of civlitie’.Footnote 103 America became an example of what a neglect of cultivation could lead to. It was necessary ‘by cutting up all mischiefs by the rootes’ to render ‘the state of their common-weales’ prosperous by forceful interference.Footnote 104

Justifications for the use of force derived from Christian but also classical thought. Although historians have seen the tactics of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, or John Smith as exercizing ‘a Machiavellian critique of the prevailing Ciceronian model of colonization’, Cicero had not hesitated to recommend violence as a principal instrument at the disposal of political actors.Footnote 105 Law separated ‘life thus refined and humanized, and that life of savagery’, Cicero wrote, but ‘if the choice is between the use of violence and the destruction of the state, then the lesser of the two evils must prevail’.Footnote 106 To Cicero, violence was justified when savage behaviour imperilled the state. In such cases, violence might be legitimately used for the sake of common interest, an idea that became a recurrent theme in Elizabethan and Jacobean writings about the use of violence in expansion. The ‘feedfights’, or burning of crops, that the English conducted in Ireland and Virginia, sometimes when in perilously short supply of food themselves, were assertions over the landscape that sought to subject local peoples to a recognition of English ascendancy. The Irish, wrote Chichester in 1605, were ‘generally so … uncyvell … the best we can do is plant and countenance some Englyshe’, but such planting required clearing the soil first.Footnote 107

James himself employed metaphors that demonstrated his understanding of cultivation as a necessary act of force. In 1624, Nicholas Ferrar recorded heated speeches in Parliament following Prince Charles’ controversial visit to the Continent to court the Spanish Infanta Maria Anna. According to Ferrar, James had proclaimed himself ‘not onely a good Husband butt a good Husbandman, who doth not onely plante good Plantes butt weede upp ye weedes that would else destroy the good Plantes’.Footnote 108 James’ play on ‘husband’ and ‘husbandman’ emphasized the patriarchal framework through which order was achieved. The widespread significance of the term ‘husbandry’ is evident from its proliferation in gardening manuals, Parliament speeches, domestic advice books, commonplace books, treatises, and sermons. ‘The people wherewith you plant’, wrote Francis Bacon in his essay ‘Of Plantations’, should include skilled labourers and ‘Gardeners, Plough-men, Labourers’, not vagrants or soldiers.Footnote 109 In short, ideal colonists were those best equipped to efface savagery through husbandry.

James also made clear that, like a gardener who uprooted the weeds that threatened the health of a garden, ‘hee did indeed thinke fit like a good horseman not allwaies to use the Spurr butt sometimes the bridle’.Footnote 110 As Ethan Shagan argued in The Rule of Moderation, a ‘coercive moderation’ dictated relationships within the hierarchical structures of early modern English society, meaning ideas of subjection were ingrained in notions of civil order.Footnote 111 The figurative language James used articulated this belief and justified action, seen in James’ rigorous campaigns against peoples in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands. Those who dwelled ‘in our maine land, that are barbarous for the most part, and yet mixed with some shew of civilitie’, James told his son Henry in 1598, differed from those ‘that dwelleth in the Iles [and] are alluterly barbares, without any sort or shew of civilitie’.Footnote 112 It would be easy to subdue the former, James wrote, by targeting the nobility and securing their allegiance to him. For the Gaelic Scots, James believed that plantation offered the best solution, ‘that within short time may reforme and civilize the best inclined among them; rooting out and transporting the barbarous and stubborne sort, and planting civilitie in their rooms’.Footnote 113 The idea of planting civility ‘in their rooms’ presents an evocative image of the intersection between the control of nature (‘rooting’, ‘planting’) and the flourishing of the ordered domestic environment (‘rooms’). James supported the expeditions that colonizers promoted in America because they aligned well with a more general view that ‘sharp conflicts’ would ‘civilize and reform the savage and barbarous Lives, and corrupt Manners of such peoples’, enabling ‘a solid and true foundation of Pietie … conjoined with fortitude and power’.Footnote 114

Once an area was successfully planted, education would allow a civil polity to flourish. Schools were ‘nurseries’ where the fruitful soil of impressionable minds were tended and taught obedience. Protestant reformers advocated education, including literacy, as a means of equipping individuals with the tools to develop their rational faculties and to serve the realm. The schoolmaster John Brinsley dedicated his treatise on grammar school education to colonial promoters including Henry Cary, the lord deputy of Ireland, and members of the Virginia council in London. To Brinsley, bringing a humanist education to Native Americans was a natural extension of the growing access to education in the British Isles, where the conversion and salvation of ‘savages’, and the ‘preservation of our owne countrie-men there already’, might be ‘rightly put in practise’ through education.Footnote 115 This would create a ‘sure foundation … for all future good learning, in their schools, without any difference at all from our courses received here at home’.Footnote 116 His view was entirely in keeping with that of many colonial promoters, from members of the Ferrar family to the author (likely Ferdinando Gorges) of a treatise on New England who claimed that ‘wee acknowledge our selves specially bound thereunto’ to ‘build [the Algonquians] houses, and to provide them Tutors for their breeding’.Footnote 117 Teaching the Irish and Native Americans English and Latin would ‘reduce them all … to a loving civility, with loyall and faithfull obedience to our Soveraigne, and good Lawes, and to prepare a way to pull them from the power and service of Sathan’.Footnote 118

From the pulpit, the preacher William Crashaw advocated Brinsley’s educational methods, while Crashaw’s friend the young minister Alexander Whitaker went to Virginia himself to set up a school in Henrico in 1611.Footnote 119 In 1619, the Virginia Company allocated a committee to oversee an English college at Henrico, placing Dudley Digges, John Danvers, Nathaniel Rich, and John Ferrar in charge.Footnote 120 Anonymous benefactors across England contributed to this cause, including an individual who styled themselves ‘Dust and Ashes’ and contributed a staggering 550l. towards the school, promising a further 450l. if the colony sent indigenous children to England to be educated.Footnote 121 Nicholas and John Ferrar’s father, Sir Nicholas, bequeathed 300l. to the college at his death in 1620, requesting at least ten Algonquian children be educated at his expense.Footnote 122 Patrick Copland, Scottish chaplain to the East India Company, became a free member of the Virginia Company after dedicating himself to this project. In 1622, after sending a manuscript copy to the Virginia Company, Copland published a catalogue of the ‘gentlemen and marriners’ who ventured funds for this ‘pious worke’.Footnote 123 Copland listed nearly 150 names from a range of social backgrounds, including merchants, sailors, pursers, stewards, surgeons, and carpenters who donated sums ranging from 1s to 30l. Copland’s efforts raised 100l. 8s 6d, and, unlike joint-stock investments, contributors expected no economic return, seeking instead to take part in ‘instructing of the children there, in the principles of Religion, civility of life, and humane learning’.Footnote 124

A London committee in 1621 discussed further appeals by Copland to build a school in Charles City, Virginia, based on the funds he had collected. Tellingly, the council decided there was a greater need ‘of a school than of churches’ to introduce ‘the principles of religion, civility of life, and human learning’.Footnote 125 Education, the council determined, was where ‘both church and commonwealth take their original foundation and happy estate’.Footnote 126 To the same purpose, Harvard College in Massachusetts, founded in 1636 – less than ten years after the foundation of the Massachusetts Bay Company – received the first English printing press in North America in 1638. The charter of 1650 aimed for the ‘education of the English & Indian youth of this Country in knowledge and godlines’.Footnote 127 Rather than being relegated to decorum alone, civility through conversion and education was to be the foundation of a civil, transatlantic polity, and would nourish pupils into accepting their prescribed places in society.

State and Estate

The state’s concern with conformity and obedience highlights shared attitudes towards authority in England and its colonies at a time when these were governed by the same men. Framed as a pious work that would bring those ‘savage, and to be pittied Virginians’ into the folds of English civility, as Richard Crakanthorpe preached at Paul’s Cross in 1608, the aim of plantation was to allow for ‘a new BRITTAINE in another world … together with our English’.Footnote 128 The crossover between these domains of rule made plantation and estate management an important indicator of the successful flourishing of English civil society. Just as the microcosm of the body paralleled the body politic, so a gentleman’s plantation was connected to the harmony of the state and imperial expansion. As one author expressed, referring to Newfoundland, the merits of plantation were twofold. Firstly, ‘[t]his countrey, which hitherto hath onely served a den for wilde beasts, shal not only be repleat with Christian inhabitants, but the Savages … may in time be reduced to Civilitie’.Footnote 129 Secondly, a sustained presence in Newfoundland would cause ‘an Iland every way as bigge and spacious as Ireland … to be brought to bow under the waight of his royall Scepter’.Footnote 130 By articulating plantation estates, and the associated responsibility of office-holding and governance, as locked in a relationship with the state, pro-colonial gentlemen sought to create ‘a new BRITTAINE in another world’ in a tangible way.

Plantation is so profoundly engrained in the American story that it is easy to forget that methods of planting colonies were a response to a process already under way in England, one that saw vast changes in attitudes to the English landscape. The Italian treatises on civility, so influential in the Renaissance, were never fully applicable to the English gentry, who retained a ‘quasi-urban’ mode of life that connected their social and political life in London to their estates in the localities.Footnote 131 As the author Barnabe Rich pointed out in Foure bookes of offices (1606), the Roman historian Livy had praised Marcus Cato for ‘his knowledge [which] was absolute both in urbanitie and husbandrie’.Footnote 132 To gentlemen who endorsed plantation, urbanity and husbandry need not be antithetical. Quite the opposite, for a ‘[s]tates-man’ gained renown through his mastery of civility and rhetoric, enabling him to manage his estate and public affairs in a way that related to ‘the greatnesse of the whole Empire’.Footnote 133 Humanist scholarship, disseminated by print, made classical pastoral works including Virgil’s Georgics more readily available, contributing to ‘a culture of active estate management involving experience’.Footnote 134

The proliferation of maps and surveys drew on the language of the common good while exhibiting malleable, at times contradictory ideas about the relationship between public and private good, in schemes often coming at the expense of common land.Footnote 135 Domestic projects used the same language found in colonial literature. The enclosure of forests, for example, would be ‘good for the commonwealth’, with ‘plantation’ bringing ‘inhabitants to a civil and religious course of life’.Footnote 136 Projectors consistently spoke of the dignity of the plough, and the call of work for the poor, coalescing with a paternalist discourse that was also apparent in overseas plantation.Footnote 137 At the same time, profiteering seemed to stand at odds with traditional concepts of nobility. Moral literature and parliamentary debates lamented the eroding divisions in social status that accompanied the successes of merchant projectors.Footnote 138

Though moralists wrote scathing denunciations of the privatization of land and the exploitation of resources by the elite, projectors benefitted from expanding literature about surveying and estate management.Footnote 139 These works reflected economic but also ideological shifts in landholders’ relationships with their estates, where gentlemen were encouraged to intimately know the conditions of the land they owned.Footnote 140 Surveyors were called upon to use mathematical precision and the language of the law to re-configure traditional tenurial relationships.Footnote 141 From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, landed properties – estates – went from being described as collections of rights and incomes to expanses of private, controlled land.Footnote 142 In The compleat surveyor (1653), William Leybourn recommended that gentlemen place surveys of their estates in their private chambers, where visual iconographies of land, gardens, and family crests ‘will be a near Ornament for the Lord of the Mannor … so that at pleasure he may see his Land before him, and the quantity of all of every parcell thereof’.Footnote 143

The libraries and studies where gentlemen were encouraged to hang their surveys were often where they also kept their globes and cosmographies, reinforcing the connection between estate management and expansion overseas. In drawing and publishing detailed maps of English counties, as of the colonies, the surveyors John Norden and John Speed indicated an interest in charting regional boundaries that related domestic cartography to imperial aspirations.Footnote 144 The frontispiece to Aaron Rathbone’s The surveyor in foure bookes (1615) depicted a gentleman with his large estate behind him, standing in a cultivated landscape with a globe at his side while trampling the satyr-like ‘folk’ figures of popular lore.Footnote 145 This image appeared between the columns of arithmetic and geometry, the latter topped with a globe labelling America, Europe, and Africa.

To land-holding gentlemen, plantation was a justifiable form of land management that established regional ascendancy and godly authority. ‘The Country is now also Described & drawne into Mapps & Cardes’, wrote John Davies to Cecil from Ireland. ‘The use & Fruit of this Survey … will discourage & disable the Natives henceforth to rebell against the Crowne of England’.Footnote 146 To Davies, plans for Ireland extended naturally to colonizing America: ‘the most Inland part of Virginia is yet unknowne’ and must be treated, Davies continued, with the same rigour as Ireland, ‘whereas now we know all the passages, have penetrated every thickett & fast place, have taken notice of every notorious Tree or Bush; All w[hi]ch will not only remayne in our knowledge & memory during this Age; but being found by Inquisitions of Record, & drawn into Cardes & mappes ar discovered & layd open to all posteritie’.Footnote 147 Davies’ words, however, highlight the predatory nature of such revelation, where landscapes seemed to come alive, becoming ‘notorious’, subject to ‘inquisitions’, and ‘layd open’ to intrusion.

Architecture, like cartography, could embody values of intervention and surveillance. The earliest English surveying manual, The boke of surveying and improvements (1523) translated the French ‘surveyour’ into ‘Englysshe as an overseer’.Footnote 148 Jacobean architecture imposed a verticality on the landscape that reflected drastic changes in rural economies and landscapes following the rise of industries like coal mining in the North East, where quick profits led aspiring members of the gentry to physically assert their status through building.Footnote 149 The ‘great re-building’ of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries reflected the increased national consciousness apparent after the Reformation and its ensuing re-distribution of Church property.Footnote 150 The enclosure of landscapes found a parallel in the architectural enclosure of stately homes, where open halls were replaced by private bedrooms and dining rooms that restricted access to select members of the household and their guests.Footnote 151 Formidable two- or three-storey houses with high gables added to the visibility of estates, enabling those who had access to the private chambers and galleries on the upper floors to look over their grounds. Though completed in the mid-seventeenth century, some of the earliest elite houses in English Barbados, St Nicholas Abbey and Draxe Hall were built in the Jacobean style. Since planters oversaw their own workforces, these high structures enabled them to dine and socialize while keeping an eye on their sugar plantations.Footnote 152 These developments happened gradually, but they indicate distinct architectural changes that shaped household relationships, reflecting the immense inequality and social exclusion perpetuated by buildings and their positionality to surrounding landscapes.Footnote 153

During the Jacobean colonization of Ireland, colonists targeted the structures previously built by the Gaelic nobility, supplanting more feudal or military manifestations of power, such as castles with forts, turrets, and narrow windows, with houses modelled after English estates.Footnote 154 In using the language of civility to praise the efforts of the Irish elite who conformed to English architectural styles, the English asserted their commitment to a larger cultural and political hegemony centred largely on London.Footnote 155 The earliest permanent architecture in Bermuda was the governor’s state house of 1620, built in stone and modelled after Inigo Jones’ Italianate architecture for the Jacobean nobility.Footnote 156 John Smith included an image of the state house, alongside other dominant architecture, in The generall historie of Virginia, its columned entryway and walled grounds allowing the building to operate as something more than just defence. The state house exuded a sense of classical authority and permanence, contrasted against the thatch roofs, small timber-framed houses, and mud huts used by workers and enslaved peoples. It was ‘in the Governours newe house’ in 1621 that a wedding took place between an Englishman and an Algonquian woman who had formerly travelled to London with Pocahontas, where the guests revelled in a ‘fashionable and full manner’ in attempts to illustrate the possibilities of settled and refined society in a prosperous plantation.Footnote 157

Through their estates, gentlemen expressed their status while using plantation management as a stated means of extending the authority of the state. In 1611, echoing the complaints of many gentlemen who had gone to colonize Ireland, Henry Goldfinch petitioned Cecil for his losses. He had ‘a Reasonable estate in England’, Goldfinch wrote, but had ‘ventered the same to plant him selfe uppon her late Ma[jest]ies landes in Ireland’.Footnote 158 Because this venture had required ‘building, planting, Inhabitting, & maintayning’ land, he had lost upwards of 2,000l.Footnote 159 Goldfinch’s petition conveyed his belief in a protected relationship between elite landholders and the Crown. He had used his estates to perform duties for the state, Goldfinch wrote, implying that his assets should be protected, locked as they were in a reciprocal relationship of fidelity and trust between obedient gentlemen and the world of Westminster.

Richard Norwood had successfully divided and mapped all of Bermuda by the mid-1610s, but it was the gentry’s rising commitment to Virginia that established a particularly powerful relationship between overseas estates and metropolitan conceptions of political responsibility. When the Virginia Company’s gentry faction gained ascendancy over its rivals in 1619, its members sought to restore the colony’s ailing reputation by modelling colonization more closely on the traditional values of landholding. The General Assembly of 1619 gathered in the church at Jamestown, where the establishment of common law reflected this change in the colony’s direction and ushered a new phase in its development. Rather than using the colony as a trading outpost or a base for piracy against other European powers, as the Earl of Warwick and Thomas Smythe advocated, gentry leaders of the London council expressed disdain for unregulated private enterprise and placed greater emphasis on landholding and settlement.Footnote 160 Although some scholars have hailed the first meeting of the General Assembly as the democratic beginnings of the American nation, the view from England was somewhat different. The establishment of English systems of law and jurisdiction exhibited a clear effort to divide and classify land and to establish hierarchical authority that would ensure its maintenance and enable the London council to retain oversight.

In reality, the rise of planter society in colonial Virginia depended on both private and public enterprise, the circulation of goods, the explosion of the tobacco market, and exploitation at all levels of society. But to pro-imperial gentlemen in London, the rise of plantations would be ensured by protecting elite authority and yoking the colony to the governing mechanisms of the polity. When the colonial administrator John Pory arrived in Jamestown in 1619, he expressed a sense of isolation at its remoteness, but he also saw Virginia as offering the ‘rudiments of our Infant-Commonwealth’.Footnote 161 Though it was ‘nowe contemptible’, Pory wrote to the ambassador Dudley Carleton, ‘your worship may live to see [it] a flourishing Estate’.Footnote 162 Pory’s letter reflected a sense of connection to England and its global interests. Though he looked back wistfully at his travels through the Continent to Constantinople, Pory embraced his role as company secretary, and returned to Virginia to serve as a commissioner in the 1620s. In requesting ‘pamphletts and relations’ of events at home, Pory connected the world of manuscript and print circulation and information-sharing in London to the fledgling polity in America.Footnote 163 When corresponding with Carleton, who was serving as ambassador in the Netherlands after time in Venice, Pory wrote as a friend but also as one officeholder writing to another, conveying a shared sense of urbanity that emerged from service to the state.

In 1620, a set of instructions and ordinances published by the Virginia Company celebrated how ‘the Colony beginneth now to have the face and fashion of an orderly state’.Footnote 164 This was due to the successes of those men of ‘good quality’ who had demonstrated ‘sufficiency’ and who were charged with ‘the government of those people’ in the colony.Footnote 165 Political service and land management operated together, since the governor had established order by dividing the colony, demarcating public land and ‘private Societies’ while ensuring the maintenance of these allotments through ‘necessary Officers’.Footnote 166 The publication included a list of the company’s hundreds of investors, who ranged from James’ secretary of state and other prominent courtiers to companies and guilds including the Grocers, Skinners, Goldsmiths, and Merchant Taylors. The investors consisted of a close network of alliances with friends and family – fathers, brothers, sons, cousins, and wives. More than 50 were esquires, and nearly 100 were knights. Southampton, Theophilus Howard, second Earl of Suffolk, Thomas West, Lord de la Warr, and several other members of the nobility had contributed more than 150l. each, as had affluent merchants and MPs like Walter Cope, Robert Johnson, and Thomas Smythe. The amounts invested do not necessarily indicate levels of commitment or interest in and of themselves, but the publication of names held them publicly accountable for their subscriptions, and, by extension, to the structure of colonization that underpinned these lists.

The Virginia Company ordinances were particularly concerned with delineating the roles and responsibilities of the councillors who convened in London. These men were expected to ‘faithfully advise in all matters tending to the advancement and benefit of the Plantations: and especially touching the making of Lawes and Constitutions, for the better governing as well as the Company here, as also of the Colonie planted in Virginia’.Footnote 167 The responsibility to govern plantations imbued gentlemen with a sense of political duty alongside an expectation of profit. Martin’s Hundred, one of the earliest plantations to emerge from the policy revisions to Virginia Company land grants in 1618, was also one of the plantations most closely connected to gentlemen in the Virginia Company. Edwin Sandys wrote that he had a general commitment to Virginia, but ‘toward Southampton & Martins Hundred in particular’.Footnote 168 Of a sample list of thirty-four colonists who arrived at Martins Hundred in September 1623, fifteen were from London, and about a third were gentlemen.Footnote 169

London councillors were expected to meet regularly to discuss colonial governance, usually on Wednesday afternoons, and were responsible for sending ‘choise men, borne and bred up to labour and industry’ to the Chesapeake.Footnote 170 ‘They shall also according to the first institution and profession of this Companie, advise and devise to the utmost of their powers, the best meanes for the reclaiming of the Barbarous Natives; and bringing them to the true worship of God, civilitie of life, and vertue’.Footnote 171 Gentlemen were to secure the success of the colony by overseeing land grants and distribution as well as regulating elections and offices, and demonstrating competent record-keeping that would assist metropolitan oversight. While four ordinances in the council’s instructions pertained to trade, and three to establishing a college, a significant eleven pertained to land.Footnote 172 These entrenched systems of indentured servitude to plantation management, and reiterated the right of company and Crown to extract revenues from any gold and silver mines that might be discovered.

To those in charge of sustaining early hundreds and plantations, the language of effacing savagery met with practical, material efforts to convey order. In the 1620s, ordinances in Virginia sought to prevent any person residing in Virginia to wear gold or silk in their apparel, ‘excepting those of the Counsill And heads of Hundreds and plantations and their wyves & Children’.Footnote 173 While the company insisted that colonists must ‘frame, build, and perfect’ houses to ensure their survival, gentlemen also arrived with objects that reflected their aspirations as colonial leaders.Footnote 174 Along with book clasps and drug jars, fragments of glass vessels and Ming porcelain have been excavated from Martin’s Hundred and Jamestown: fragile, precious objects that indicate attempts to reflect the status and lifestyle gentlemen enjoyed in England. The 1624 inventory of George Thorpe’s estate in Virginia, one of the earliest of its kind, is illuminating. Kept in the vast collection of Chesapeake plantation papers owned by the MP John Smyth of Nibley, the inventory consists in large part of apparel: a lined velvet cloak, a black silk grosgrain suit, a black satin suit, silk garters, pantofles, velvet jerkins, gloves, and russet boots.Footnote 175 Along with clothes, Thorpe’s most expensive objects were featherbeds, pillows, gilt bowls, and silver cutlery. Land and the material culture of plantation that gentlemen sought to cultivate – those ‘healthfull Recreations’ and demonstrations of civil authority – helped to link the ‘Adamantine chaines’ of ‘Societie’ across the Atlantic, from Martin’s Hundred to the Middle Temple.Footnote 176

*

From Francis Bacon’s The Advancement of Learning (1605) to Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion (1612), Jacobean oeuvres often placed geography at the centre of the national imagination, employing horticultural language that related cultivation to virtue.Footnote 177 This served to frame colonization as a natural extension of the civilizing project while offering a practical method of carrying it out. As early as the 1590s, George Chapman’s celebratory verses on Guiana viewed the civilizing project – ‘Riches with honour, Conquest without bloud’ – as contingent on subduing Native Americans while simultaneously creating a society joined through land management and building.Footnote 178 The English Atlantic was one where ‘[a] world of Savadges fall tame before them’ but also where leisure made ‘their mansions daunce with neighborhood’, conveying an Arcadian world of palaces and temples that evoked the sensual delights of elite gardens.Footnote 179

Though couched in language of lush abundance and technical innovation, in pleasing cultivation rather than brutal conquest, ‘planting’ involved a recognition of violent supplanting. It took a translation of the French writer Michel de Montaigne’s essays by the second-generation Italian migrant John Florio to puncture the ideologies of colonization. The Tupinambá in Brazil ‘are even savage, as we call those fruites wilde, which nature of hir selfe … hath produced’, Montaigne wrote. ‘[W]hereas indeede, they are those which our selves have altered by our artificiall devises, and diverted from their common order, we should rather terme savage … we have bastardized [true virtues], applying them to the pleasure of our corrupted taste’.Footnote 180 Prevailing discourse written by English policy-makers and colonial promoters, however, celebrated the pleasures of plantation without expressing fears that it ‘diverted’ from virtue and order. Unlike Montaigne’s praise of a benign Eden, the English continually conveyed the exploitation of nature as essential to their civil designs and to strengthening their state, where civility involved not just the urban but a specific connection to the localities.

Arriving in Barbados in 1631, the Essex gentleman Henry Colt expressed frustration at the behaviour of the young Englishmen he encountered on the island. Even as he struggled to navigate Barbados’ alternative ‘societye’ and its adapted codes of conduct, Colt’s sense of responsibility lay in upholding the traditional virtues embodied in the upright and committed gentleman, and he condemned the lack of husbandry that sullied the reputation of pleasure-seeking colonists.Footnote 181 Ideas of savagery and cultivation suffused his articulations of colonial responsibility. ‘You are all younge men, & of good desert’, Colt wrote, yet ‘[y]our grownd & plantations shewed whatt you are … What digged or weeded for beautye? All are bushes, & long grasse, all thinges caryinge the face of a desolate & disorderly shew to the beholder’.Footnote 182 An ordered plantation manifested the ability to subjugate territories and those ‘naked Indians paynted red, & feathers in their heads’ who lived in them.Footnote 183 Cultivation, and enjoying the fruits of the soil that industrious plantation yielded, would ensure the success of future enterprises. When Colt rebuked his idle peers, he mirrored the language of domestic surveying literature: ‘doe but consider what you are owners of’.Footnote 184