Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Tables and Charts

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- 1 The Opposition's Year of Living Demonstratively

- 2 A Tectonic Shift in Malaysian Politics

- 3 The Ethnic Voting Pattern for Kuala Lumpur and Selangor in 2008

- Postscript: Anwar's Path to Power goes via Permatang Pauh

- Index

- Plate section

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 October 2015

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Tables and Charts

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- About the Authors

- Introduction

- 1 The Opposition's Year of Living Demonstratively

- 2 A Tectonic Shift in Malaysian Politics

- 3 The Ethnic Voting Pattern for Kuala Lumpur and Selangor in 2008

- Postscript: Anwar's Path to Power goes via Permatang Pauh

- Index

- Plate section

Summary

A nation trudges along by securing symbolic events, iconic periods and defining personages as pillars for its central storyline. This acquired storyline goes backwards and forwards at the same time, generating common concepts and injecting a common understanding of the nation into its population.

In the case of Malaysia, there is the idea of the first Baling talks of December 1955 when the communists were outplayed by the anti-communist parties; there is the image of the first premier Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra raising his arm in a salute as he declares independence from the British on August 31, 1957; there is the national mosque, the parliament building, the Kuala Lumpur Tower and the Petronas Twin Towers; there is the Malaysian flag; and there are depictions of the police and the armed forces aided by civilians stymying Indonesian infiltrators in the 1960s.

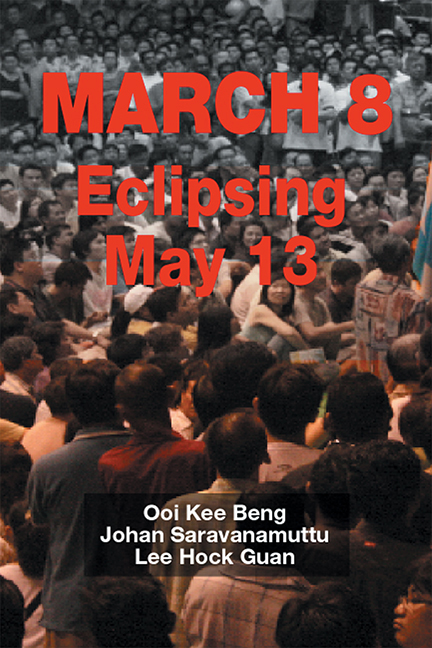

And then there are images that the nation would rather forget. These include Singapore's separation; the racial riots of May 13, 1969 in Kuala Lumpur, with burning buildings and cars spread throughout the city; and lately the Education Minister raising an unsheathed keris before an assembly of UMNO Youth members. Recently, pictures of large demonstrations, along with police water cannons, have also begun to etch themselves onto the Malaysian psyche.

With the advance of the mass media, more such images will in the near future uncontrollably bore themselves into the minds of the nation.

However, the prize for the country's greatest fixation must still go to May 13. This is not because there are that many pictures publicly available for viewing, but because changes stemming from it were so comprehensive and profound.

In its eagerness to curb trouble-makers, the government of the day used the proverbial hammer to kill the ant. In 1971, muffling legislations were pushed through a chastised parliament, including amendments to the Sedition Act of 1948, which overruled parliamentary immunity among other things; the Constitutional (Amendment) Bill that forbid discussions about sensitive issues such as citizenship, the national language, the special position of the Malays, the legitimate interests of non-Malays, and the sovereignty of the sultans; as well as the Universities and University Colleges Act, which strongly denied students from participation in political activities.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- March 8Eclipsing May 13, pp. 1 - 5Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2008