Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

2 - What is a Mask?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 February 2024

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Mask Crescent: Distribution of Masks and Masking in Africa

- 1 Mask Distribution and Theory

- 2 What is a Mask?

- 3 Masks and Masculinity: Initiation

- 4 Secrecy and Power

- 5 Death and its Masks

- 6 Women: Pivot of the Masks

- 7 Masks and Politics

- 8 Masks and the Order of Things

- 9 Masks and Modernity

- 10 Memories of Power, Power of Memories

- 11 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Sources for Ethnographic Cases

- Picture Credits

- Index

Summary

Explaining masks: The Magritte effect

A standard riddle of the Cameroonian Dìì questions whether the mask is an animal or a man. The correct answer is that it is neither: ‘Below it is a man as an animal, but the upper part is a spirit.’ One could just as well answer that it is both, but the Dìì choice is that it is neither: so its own category. This particular Dìì mask covers only the upper part of the body, and the legs are naked; in some performances, the genitals of the dancer should be in sight, to prove he is a man, a circumcised one, and thus authorised to dance. Such a riddle illustrates a kind of ‘Magritte effect’ that masks produce, using the felicitous expression of Jean-Pierre Warnier: the masking apparition blends the thing and its representation, finding both its essence and its source of power in exactly that semantic confusion.

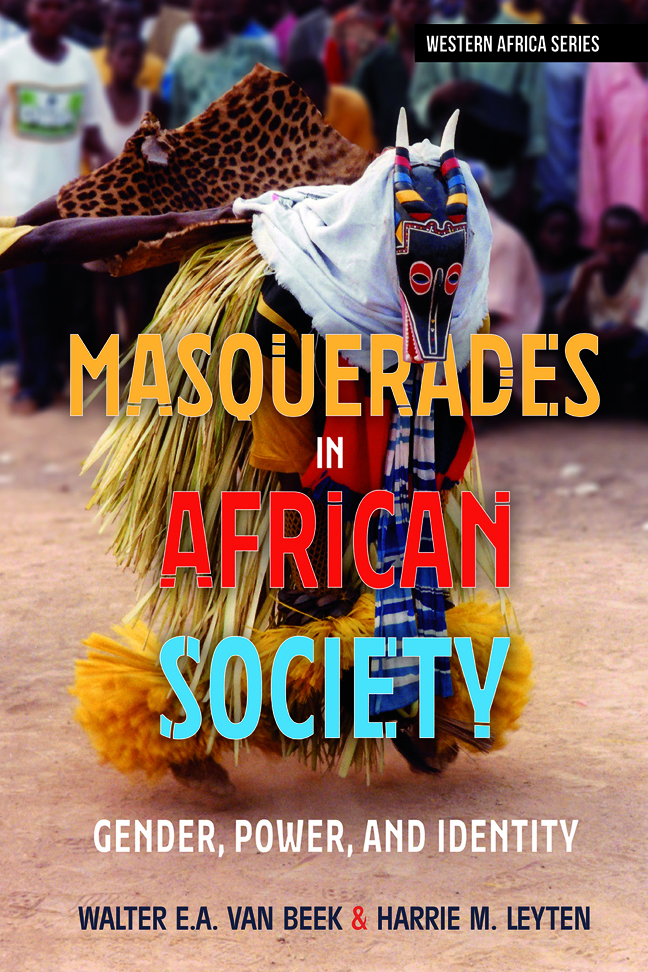

What do we mean by a ‘mask’? In Western culture, what is called a ‘mask’ in a museum exhibition or art gallery is in fact a face covering. In this book we call these ‘headpieces’, ‘tops’, or ‘face covers’, for we follow another definition of a mask, namely the African one. What informants call a mask is the entire costumed appearance, including the headpiece, the clothing or body cover, and the adornment on arms, legs, and feet, as well as the paraphernalia it holds in its hands: whips, whisks, sticks, adzes, or spears. In some cases, the same costume and headpiece may even become a different mask by simply changing the accessories and attributes. So we use the emic African definition: a ‘mask’ means costume + top + paraphernalia, coupled with, evidently, an invisible dancer inside; dance and music may be added to this definition. There are some cases where not all criteria apply, but together they cover the great majority of masks in Africa. Though the hidden face is essential, in some instances the face is, very pointedly, in sight, while the apparition is still considered a mask; those exceptions occur within specific settings, depending on the occasion, and above all on the presence or absence of a non-initiated audience. In all our ethnographic cases there is a vernacular term for mask, and in all masking societies masks are defined as a total apparition characterised by anonymity.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Masquerades in African SocietyGender, Power and Identity, pp. 47 - 78Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2023