Mediators, Contract Men, and Colonial Capital

Mediators, Contract Men, and Colonial Capital Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Prospectors, Politicians, and the Question of “Progress”: The First and Second Gold Booms in Wassa

- 2 Labor Recruitment in the Nineteenth Century: The Place of Practicality

- 3 Disrupted Recruitment at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: Women, Whites, and Other Labor Agents

- 4 Government Strategies for Assisting the Mines

- 5 Labor Agents, Chiefs and Officials, 1905–1909: The Incorporation of the Northern Territories’ Labor Reserve

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

2 - Labor Recruitment in the Nineteenth Century: The Place of Practicality

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Prospectors, Politicians, and the Question of “Progress”: The First and Second Gold Booms in Wassa

- 2 Labor Recruitment in the Nineteenth Century: The Place of Practicality

- 3 Disrupted Recruitment at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: Women, Whites, and Other Labor Agents

- 4 Government Strategies for Assisting the Mines

- 5 Labor Agents, Chiefs and Officials, 1905–1909: The Incorporation of the Northern Territories’ Labor Reserve

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

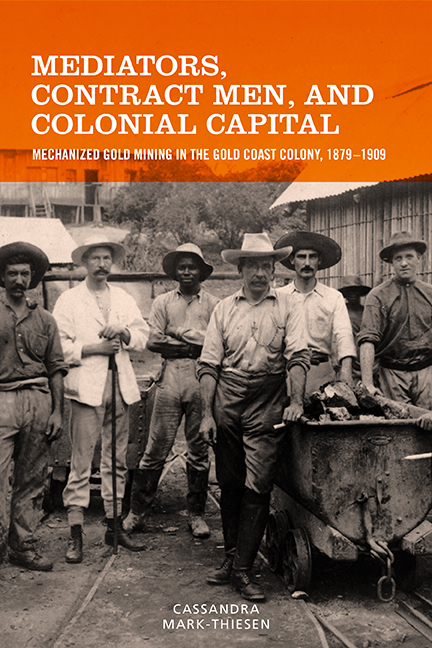

As we saw in chapter 1, rapid commercial expansion and the loose political relationship between the mines and the colonial administration promoted a special brand of economic pragmatism in West African gold mining. This chapter examines the consequences of these conditions through the lens of the labor market. Although the Gold Coast's emancipation proclamation of 1874 might have helped to bring some individuals into the employment of the mines who otherwise would have been forced to work for their masters, most former slaves did not seek out wage labor as a primary means of supporting themselves. And although the mines drew the large part of their labor force from southern Ghana during the first and second gold booms, many mine managers still viewed local labor as a problem that needed solving. Local Akan men and women tended to work on a casual and flexible basis, which in the eyes of the managers was too costly and inconsistent an option. On the other side of the labor spectrum stood one particular category of employee: the “agreement boy,” or contract man. Most managers agreed that it was vital “to encourage the boys to work on contract.” As one manager in neighboring Asante explained, “We get more work done and its [sic] far cheaper [and] it gives better satisfaction to both parties.” Men working on a contract-basis were favored by the companies because they required less supervision and less immediate capital due to the extended pay system. Furthermore, over the course of time they achieved a level of skill and efficiency that was essential to underground mining. Migrant laborers made up the bulk of this group in the nineteenth century. They were overwhelmingly Liberian Kru laborers, whom foreign employers often referred to as the “Irishmen of West Africa,” due to their humble yet hard work in the burgeoning palm-oil trade, as well as their diligent service in the British Royal Navy's antislavery patrols. They became the mining sector's most valuable workers during its initial decades of existence for their ability “to handle machines, to stoke, and generally to show the other natives both how to work and to exercise care.” Nevertheless, mine managers did not always get what they wanted.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Mediators, Contract Men, and Colonial CapitalMechanized Gold Mining in the Gold Coast Colony, 1879–1909, pp. 52 - 100Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018