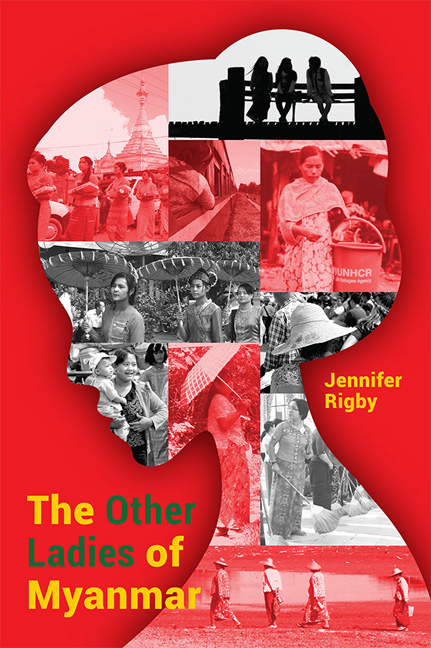

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Timeline

- 1 The Activist: Cheery Zahau

- 2 The Feminist Buddhist Nun: Ketu Mala

- 3 The Survivor: Mi Mi

- 4 The Businesswoman: Yin Myo Su

- 5 The Environmental Campaigner and Princess: Devi Thant Cin

- 6 The Artist: Ma Ei

- 7 The Refugee Sexual Health Nurse: Mu Tha Paw

- 8 The Rohingya and Human Rights Champion: Wai Wai Nu

- 9 The Farmer: Mar Mar Swe

- 10 The Pop Star: Ah Moon

- 11 The Politician: Htin Htin Htay

- 12 The Archer: Aung Ngeain

- Conclusion

- About the Author

11 - The Politician: Htin Htin Htay

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Timeline

- 1 The Activist: Cheery Zahau

- 2 The Feminist Buddhist Nun: Ketu Mala

- 3 The Survivor: Mi Mi

- 4 The Businesswoman: Yin Myo Su

- 5 The Environmental Campaigner and Princess: Devi Thant Cin

- 6 The Artist: Ma Ei

- 7 The Refugee Sexual Health Nurse: Mu Tha Paw

- 8 The Rohingya and Human Rights Champion: Wai Wai Nu

- 9 The Farmer: Mar Mar Swe

- 10 The Pop Star: Ah Moon

- 11 The Politician: Htin Htin Htay

- 12 The Archer: Aung Ngeain

- Conclusion

- About the Author

Summary

HTIN HTIN Htay is speaking in a low, urgent voice. The late afternoon sun is creeping around the roof of her wooden house, throwing shadows on the decked balcony where we are speaking. Confused cockerels are crowing below us.

She is telling me her childhood memories.

“In this village here, at midnight, the government soldiers came to force us to relocate to other places,” she says.

“I remember. I was eight years old. We had to move before 10 a.m. They said that if anyone remained in the village they would be killed. In fact, they said we would be like ash, flown away into the air, finished.”

Terrified by the threat, Htin Htin's family fled as instructed, taking very little other than what they had with them at that moment. A few days later, they went back to see what food or personal items they could collect.

“We went to check the village. I saw a lot of dead bodies, being put under the bridge. So I said to my mum, what is that? And she told me not to look, it is too scary. But I saw a woman praying to the army not to arrest her husband, so they cut off her hands and shot the husband. I saw that,” she says.

It's a long time ago — Htin Htin Htay is now thirty-four years old — but she still remembers what she saw, and what, as a child, she shouldn't ever have had to see, back in the 1980s and early 1990s in military-run southern Myanmar.

She goes on: “And then a doctor who had come to cure diseases, they asked him about his background with the rebel group. He did not answer, so they cut off his tongue and tortured him, and he died. The villagers could hear him yell and shout because of the pain, but nobody dared help him. I saw that kind of thing when I was eight years old. That is my background, growing up in a black area.”

When talking about Myanmar's conflict-hit areas, a black area means a place held by insurgents or ethnic armies (white is government-controlled, and brown contested). For Htin Htin Htay, that was her home, the village of Oattu in Tanintharyi region, the south of the country — about an hour's motorbike ride from the nearest big city, Dawei.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Other Ladies of Myanmar , pp. 108 - 116Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2018