Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Timeline

- 1 The Activist: Cheery Zahau

- 2 The Feminist Buddhist Nun: Ketu Mala

- 3 The Survivor: Mi Mi

- 4 The Businesswoman: Yin Myo Su

- 5 The Environmental Campaigner and Princess: Devi Thant Cin

- 6 The Artist: Ma Ei

- 7 The Refugee Sexual Health Nurse: Mu Tha Paw

- 8 The Rohingya and Human Rights Champion: Wai Wai Nu

- 9 The Farmer: Mar Mar Swe

- 10 The Pop Star: Ah Moon

- 11 The Politician: Htin Htin Htay

- 12 The Archer: Aung Ngeain

- Conclusion

- About the Author

7 - The Refugee Sexual Health Nurse: Mu Tha Paw

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Timeline

- 1 The Activist: Cheery Zahau

- 2 The Feminist Buddhist Nun: Ketu Mala

- 3 The Survivor: Mi Mi

- 4 The Businesswoman: Yin Myo Su

- 5 The Environmental Campaigner and Princess: Devi Thant Cin

- 6 The Artist: Ma Ei

- 7 The Refugee Sexual Health Nurse: Mu Tha Paw

- 8 The Rohingya and Human Rights Champion: Wai Wai Nu

- 9 The Farmer: Mar Mar Swe

- 10 The Pop Star: Ah Moon

- 11 The Politician: Htin Htin Htay

- 12 The Archer: Aung Ngeain

- Conclusion

- About the Author

Summary

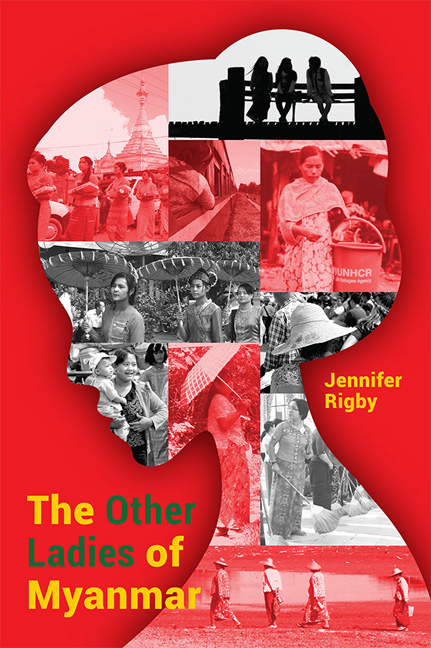

THERE IS a persistent Western myth that the Burmese language has no word for vagina. It's a convenient symbol for journalists, often used to represent Myanmar's sexual repression and lack of reproductive rights for women.

Unfortunately for the neatness of the analogy, the myth is not true. There are direct translations for vagina in Burmese and in many of Myanmar's other languages. And in rapidly developing, worldly Yangon, sex is often on show: condoms are on sale in some corner shops, some bold young women have started to dress as sexily as they like, and couples canoodle under strategically placed umbrellas at sunset by Kandawgi lakeside.

There's a dark side to this too; there are brothels in many towns, and even so-called tinsel bars, where men pick their women by throwing strings of glittery paper around their necks and paying for their time and “attention”.

However, none of this means that talking about sex in this country is easy.

Mu Tha Paw is thirty-four years old. She is Karen, part of an ethnic group who live mainly in Myanmar and Thailand. They have a different language, traditions, and even dress than the ethnic Bamar people who make up around 70 per cent of Myanmar's population.

And the Karen approach to sex is about as taboo as it gets. While the Karen language does have a word for vagina — poe tha klayi, which literally means “the way that the baby comes out” — it's basically unmentionable, rarely used even in a family or health setting.

That's why it's a shock to hear Mu Tha Paw breezily talking about vaginal exams, IUDs and the contraceptive implant (often using the English terms) within two minutes of sitting down next to me, in a bamboo-shack café on the roadside next to Mae La refugee camp in Thailand.

But then, Mu Tha Paw is no ordinary woman. She is a sexual health nurse and a refugee, one of hundreds of thousands of Karen who fled war in their homeland of Myanmar, and she has trained herself out of embarrassment because she wants to help other women.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Other Ladies of Myanmar , pp. 67 - 73Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2018