John Wayne. For so many men that came of age during the Cold War era, he was, with Hollywood’s blessing, the epitome of the ideal self-made man who proved his masculinity with cool-headed courage under fire.1 More than anyone else, the “Duke” set male expectations for intrepid wartime behavior at the midpoint of the twentieth century – when the United States, fresh from a victorious “hot war,” faced a far vaguer cold one with indistinct combatants and fuzzy boundaries. Wayne’s breakthrough performance in Sands of Iwo Jima (1949) was a defining role for the actor, if not a generation of young men who felt they had missed out on their chance for heroism in World War II. Wayne’s Sergeant Stryker was tough, disciplined, a “clear-cut hero.” The imitation seemed so authentic that one young marine lieutenant heading to Vietnam in 1968 contrasted his own “self-doubt and insecurity” with the imagined bravery of the Hollywood star.2

The male ideal embodied by Wayne and created by Hollywood replicated itself in many facets of American popular culture during the Cold War, perhaps most pervasively on magazine racks across the country and in the post exchanges on military bases around the globe, nestled within the pages of men’s adventure magazines. These “macho pulps” trumpeted the exploits of larger-than-life, self-satisfied men, valiant on the battlefield and accomplished in the bedroom. These warrior heroes were physically fit, mentally strong, and resolutely heterosexual. At the same time, men’s adventure magazines alternatively portrayed women as threat or spoil, exotic temptresses who were as dangerous as they were desirous.3

How the Vietnam generation attempted to make sense of these sometimes contradictory and often unattainable roles when they found themselves in Vietnam is the subject of this book. Unlike previous wars fought by American soldiers and depicted in graphic and gaudy detail in the pulps, GIs arriving in Southeast Asia with John Wayne fantasies in their heads found an environment starkly different than the theaters of World War II and, to a lesser degree, Korea. How, then, did soldiers reconcile their frustrated expectations with the reality of Vietnam?

A Male story from January 1964 illustrates the sort of adventures that some GIs in Vietnam might have hoped to encounter there, or at least a variation of the sort. The tale features a downed US Army pilot in World War II working behind enemy lines with Kiev “love gang girls” and “outcast gypsy dancers.”4 The accompanying artwork showcased a buxom brunette in a low-cut red top, carrying a rifle next to our “concrete-nerved” hero as they eluded chasing Nazi soldiers. Stag’s February 1967 “Nude Tribe Caper” equally contained many of these magazines’ clichés. Artist Earl Norem’s enticing illustration displays our champion held at gunpoint while surrounded by bare-breasted local Chilean women. “Peacetime in suburbia had no charms” for this marine veteran turned contract intelligence officer. After brawling his way through most of the plot, he has sex with a “gorgeous blonde” before story’s end. There we find the enemy is none other than Nazi doctor Kurt Mengel – clearly, a reference to “Angel of Death” Josef Mengele – who is raising Adolf Hitler’s son, the product of artificial insemination. The blonde, of course, proves to be a Nazi spy and is killed off “without compassion.”5

Considered by the era’s cultural critics as disposable consumer kitsch, perhaps because of their formulaic writing and flamboyant artwork, these magazines’ impact on the mass culture of the Cold War mostly has been discounted. Never mind that United States senators, like New York’s Jacob K. Javits, were writing letters to magazine editors, or, that by the mid 1960s, they had a collective circulation of roughly twelve million copies a month. Too easily dismissed as low-brow art or “throwaway, hardboiled writing,” men’s postwar pulps offer deep insights into an overlooked source of how American masculinity was broadcast during the Cold War era.6

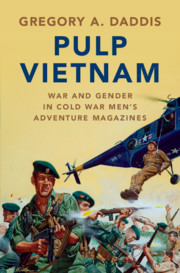

Fig. I.1 Stag, February 1967

In fact, gritty adventure stories that were the lifeblood of postwar macho pulps struck a chord with many American men seeking inspiration, stability, and identity in an uncertain postwar world. Despite having rescued the globe from totalitarianism during World War II, Americans entered the postwar period with shaky confidence. The first two decades of the Cold War was a period of immense change – socially, culturally, and politically. The September 1952 issue of Male, for example, included an exposé on “How Stalin Stole Our B-29,” followed immediately by a story from Dr. Shailer Lawton on the “million marriages … in constant jeopardy because of deep-seated, sexual inferiority complexes.” Men’s adventure magazines both manifested these popular fears and offered an antidote for men struggling to prove their manhood. In short, the construction of warrior heroes in the pages of macho pulps was a response to many Americans’ fears inspired by the twin forces of international communism and a postwar consumer culture at home.7

As a corrective, adventure magazines in the 1950s and into the mid 1960s depicted the ideal man as both heroic warrior and sexual conqueror. War stories illustrated the exploits of courageous soldiers, fighting against the “savage” enemy in foreign lands, and defending democracy in a harsh world where the threat from evil actors always seemed lurking. Sex underscored nearly all of these tales, with pulp heroes rewarded with beautiful, seductive women as a kind of payoff for their combat victories. Within these popular magazines – boasting titles like Man’s Conquest, For Men Only, and Man’s Epic – men courageously defeated their enemies in battle, while women were reduced to sexual objects, either trivialized as erotic trophies or depicted as sexualized villains using their bodies to prey on unsuspecting, innocent men.8

Adventure mags also sought to strike a chord with their primary readership: working-class young men, the same demographic that disproportionately fought a long and bloody war in South Vietnam. Working-class males read flashy stories of their fathers’ generation who, during World War II, conquered not only their enemies but women as well.9 These men, then, consumed a form of masculinity that was tough, rebellious, and decidedly anti-feminine. Read a different way, however, these magazines might also be seen as a form of entertainment and escapism from deep class anxieties and fears about not measuring up in a rapidly changing postwar society.10

Yet it was the hypermasculine narratives, not the subtext of anxiety,that helped shape the attitudes of young men who went to war in Southeast Asia during the mid to late 1960s. One lieutenant recalled how “men’s magazines were associated with home, and we read them, owned them, and traded them as if they were gold.” Another veteran remembered that the “most widely-read literature among the guys” was “comic books and adventure stories,” filled with pictures of “some guy killing somebody and the bare-breasted, Vietnamese-type, Asian-looking woman.”11 In fact, men’s adventure magazines regularly appeared on the list of top sales in the post exchange (PX) system in Vietnam. Thus, we might think of these magazines as both cultural text and cultural phenomenon. Not only did they foster ideas about what it meant to be a man, but they also helped their readers negotiate those meanings within their daily lives, both at home and abroad.12

Indeed, in many of these magazines, letters to the editor contained feedback from soldiers deployed overseas, including those serving in Vietnam. The May 1968 issue of Man’s Illustrated included three letters from soldiers deployed to Vietnam, all serving in different provinces. One noted how “We grunts don’t have much to look forward to by way of pretty faces.” Luckily for the young private, the March issue included a pictorial of Joan Brennan, the “prettiest Irish lass” he had seen and over whom his squad mates “flipped.”13

Moreover, many veterans themselves wrote stories for these magazines, suggesting important linkages between war and society during the 1950s and 1960s, and as such they were one of the few venues that specifically connected martial valor with sexual entitlement and violence with virility.14 Neither comics nor television shows nor John Wayne movies so purposefully melded war with sex. If there was a dominant narrative at play in these magazines, that paradigm unabashedly fused together violence and sexuality.15

Pulp Vietnam thus explores how men’s adventure magazines defined masculinity during two crucial decades of the Cold War era and suggests how that definition may have helped shape American soldiers’ expectations in Vietnam – expectations that were in stark contrast to what GIs found in Southeast Asia. These magazines offered young men a model of masculinity that was physically powerful, emotionally shallow, and sexually aggressive. By the time soldiers arrived in Vietnam, many had an explicit, albeit constructed, vision of how a conquering warrior should behave. Did realities in Vietnam enable these men to act on their expectations when confronted with Vietnamese people, friend or foe, and especially women?16

At its core then, Pulp Vietnam argues that men’s adventure magazines from the post-World War II era crafted a particular version of martial masculinity that helped establish and then normalize GIs’ expectations and perceptions of war in Vietnam. Cold War men’s magazines, like no other medium in contemporary popular culture, inundated American adolescents and men with idealized storylines of wartime heroism coupled with the sexual conquest of women. Such magazines correlated a kind of sexual prerogative with military service, making one the reward for the other.17

By comparing the stories and imagery in men’s adventure magazines with soldiers’ memoirs, oral histories, and court-martial proceeding testimonies, Pulp Vietnam asks whether male soldiers in Vietnam described their actions and experiences in language similar to the tales that filled the pulps, and focuses particularly on whether these adventure magazines may have shaped the ways that some soldiers thought of war and of women.18 Such an undertaking ultimately emphasizes the broader connections between war and society, appraising the role of popular culture at home with soldiers’ actions overseas. Historians commonly claim that basic training provoked an aggressive heterosexuality in young men, and it is likely that drill instructor outbursts of “you dirty faggot” or “can’t hack it little girls” engendered attitudes that contributed to violence or hostility against women. Yet it seems just as important, if not more so, to examine the preexisting sociocultural dynamics that prepared GIs to think and perform in certain, violent ways. How the home front affected soldiers’ behaviors in Vietnam is key to my analysis.19

In large part, Pulp Vietnam rests on the notion that popular representations of war often entice young men by relying on heroic language and imagery. They help to define certain expectations, even those that view exaggerated, militarized masculinity and sexual conquest as a natural component of war.20 The September 1966 issue of Stag, for example, published a letter in its “Male Call” section from a sergeant stationed on a California base. Along with other non-commissioned officers, he was preparing for deployment to Vietnam and had enjoyed an article on “Bachelor Girls Who Prey on Married Men.” Most of the NCOs in the unit, in fact, were married but stationed too far from home for weekend visits. “When you’re in the field 72 hours at a time, a man needs some relaxation,” the sergeant confessed. “If it wasn’t for the chicks around here who overlook the fact we’re married, I think we’d all go off our rockers.” Military service as stereotyped in men’s adventure magazines promised heroism and sexual satisfaction, unabashedly linking them together in a symbiotic relationship.21

These same magazines, however, were poor preparation for actual war. They left readers with a distorted view of battle and often unprepared to deal with the realities GIs faced. Combat wasn’t adventurous. It was deadly, impersonal, and corrupting. The warrior hero illusion never emerged as a tangible reality.22 What men’s adventure magazines did, then, was create a narrative framework that bestowed upon young men a warped knowledge of war and sex, one that helped make violence against the Vietnamese population seem acceptable, if not a routine feature of overseas military service. War might have been alien to working-class American teens in the 1950s and early 1960s, but its portrayal in the postwar “macho pulps” proved immensely alluring to many young boys who believed combat would help make them into men.23

On one hand, the experience of combat in Vietnam was far different than the pulp stories, and that gulf between expectation and reality left soldiers with little reassurance they were doing the right thing. The magazines presented a scenario of heroic battlefield exploits that rarely, if ever, were realized in the largely unconventional fighting of Vietnam. The “man triumphant” never emerged. As one veteran recalled, his “romantic notions of war began to dull as the exhausting, frustrating months passed with nothing but a few snipers’ bullets and the shells of mortarmen to break the tedium.” Slowly he began to suspect that his “pursuit of glory was a hopeless task.”24 Of course, many American GIs who fought in World War II and Korea also found that they had little control over events that might determine life or death. The murky political–military struggle in Vietnam, though, seemed only to exacerbate the disconnects between anticipated heroic deeds and genuinely brutal wartime acts, while the gradual loss of public support for the war further challenged the notion that combat heroism would be the man-making experience that the magazines had promised.25

If the pulps’ combat narratives differed so much from reality, then perhaps, on the other hand, American soldiers’ relations with local women might align more closely with the sexual champion depicted in the magazines. Frustrated that combat in Vietnam had left them few opportunities to “prove” their manhood, soldiers who sought to establish their dominance in relations with the population could find convenient examples in men’s adventure magazines. As one writer has suggested, “carnal conquest” was a way for soldiers to compensate for “military impotence in fighting an unwinnable war.”26 Via sexual conquest or violence, GIs could still measure up to the myths being propagated within the magazines. Surely, this redirection of hostility was made easier by the tactic of dehumanizing the enemy that was so central to contemporary basic training methods. Yet the pulps’ basic depictions of women – as sexually promiscuous and available, if not rightful objects of conquest – must be considered if we are to better understand the sexual violence in Vietnam committed by American soldiers.27

Accounts from veterans in combat suggest these men had few opportunities for heroic acts on the battlefields of Vietnam; they had little chance to resemble the warriors of pulp magazines. But when dealing with the population, GIs were in positions of relative power. They could control decisions of whether or not a hut was burned, a woman raped, or, in lesser ways, treated as a “spoil” of war. As one veteran recalled, “I had a sense of power. A sense of destruction … in the Nam you realized you had the power to take a life. You had the power to rape a woman and nobody could say nothing to you … It was like I was a god. I could take a life. I could screw a woman.”28

It’s important to make clear that I am not accusing all or most US servicemembers in Vietnam of committing rape or sexual violence. This is not a detailed study of the actual sexual atrocities committed by ordinary GIs in Vietnam. Rather, Pulp Vietnam focuses more on culturally constructed expectations, and a main expectation derived from men’s magazines was that soldiers could – and, perhaps, should – conquer the local female population while serving overseas. Stories that portrayed “warrior heroes” exerting their dominance over seemingly threatening yet desirous women helped to normalize wartime interactions based largely on accepted notions of power disparities between men and women during the 1950s and 1960s.29

Pulp Vietnam, therefore, is as much about Cold War gender conceptions as it is about pulp narratives of wartime heroism and sexual conquest. In truth, they are intimately connected. If soldiers did make the choice to engage in sexual conquest in Vietnam – which was without consent and by force in many instances – men’s magazines provided a graphic framework rarely, if ever, found in other forms of popular media. They alone established perceptual norms that suggested aggressive behavior in wartime, against both the enemy and women, was not just acceptable, but admirable.30 And while none of this is to argue for direct causality – reading macho pulps did not lead men inevitably to rape – we still must consider the role socialization plays in male soldiers’ wartime behavior. If young GIs were going to act out their frustrations in Vietnam, men’s adventure magazines offered a graphic instruction manual.31

Young, naïve, and idealistic Americans went off to Vietnam expecting an affirmation of their manhood in the cauldron of war. When their experiences in combat or in rear areas did not match the pulp magazine stories of wartime heroism and triumphalism, many of these young men were left searching for some form of compensation or for connection between fantasyland and reality. Some found it in the realm of sex. Having grown up with tales that coupled martial valor to sexual conquest, the connection would not have been difficult to make.32

Yet as alluring as the macho pulp fantasies were, they fabricated a world for young readers that veered widely from actual wartime experiences. That the knowledge gained from these magazines was so flawed helps explain, in part, the vast discord between the imagined war in Vietnam and the real one fought by American soldiers far from the world of pulp fiction.33

Pulp Fictions: Men’s Magazines in Cold War America

In their depictions of wartime heroism and sexual conquest, Cold War men’s adventure magazines were not just pop culture products representative of their era, but rather drew upon a decades-long expansion of a market that reached into millions of American homes after World War II. We tend to forget the presence of a print magazine culture at the midpoint of the twentieth century and how much it contributed to popular ideas on masculinity and femininity. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), for example, is largely a reaction to the images of domesticated women emerging from popular magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal and Good Housekeeping.34 In order to fully grasp the significance of mid-century adventure magazines, we need to understand their origins and the development of a market for contemporary ideas on militarized masculinity, a key theme that defined the Cold War macho pulps.

By the mid 1950s, men’s adventure pulps had evolved from earlier forms of magazine publishing while maintaining many of their forerunners’ core themes. Though national magazines dated back to the middle of the nineteenth century – Harper’s, for example, was founded in 1850 – technological advances in the late 1800s allowed publishers to produce and distribute higher quantities at lower prices for a wider readership. Frank Munsey’s The Argosy illustratively cost only fifteen cents in 1912, a full twenty cents cheaper than Harper’s. The latter fell in the category of “slicks,” so named for their higher-quality (and costly) paper and, thus, more middle-class readership.35 “Pulps,” however, were produced from a wood-fiber base and quickly earned a poor reputation for “crudely written stories [and] embarrassingly garish covers” that “generally contained little to attract intelligent readers.”36

With their emphasis on formulaic fiction stories, though, pulps held broad appeal. Argosy alone reached a circulation of half a million by 1907. Moreover, in the early twentieth century, the price of all magazines became even more affordable thanks to advertising revenue, a key innovation of national periodicals.37 Before long, all-fiction periodicals – Popular, Blue Book, Adventure – were being eagerly consumed by an enthusiastic market. Collections of crime stories, such as Black Mask, and other detective and western “hero pulps” soon followed, magazines that were purposefully sensational in title and content. And within this newer “hard-boiled” adventure fiction emerged an aggressive form of American masculinity.38

To be sure, some magazines like Esquire, founded in 1933, cultivated an upper-middle-class male audience. Within the pulps, though, the heroic male icon represented something more visceral. Whether a hard-boiled detective fighting back against the social and economic conditions of the Depression era or Tarzan of the Apes carving out space in a savage, primitive jungle, these men were autonomous, physically powerful, sexually potent, and interminably courageous. These were manly men. In large sense, the depictions of manliness advanced by the pulps idealized what their readers already considered to be real men. If magazines themselves were exemplars of modern mass production, then the champions within their covers gave hope that the mythic “frontier hero” was alive and well in contemporary American society.39

The relationship between the pulps and gender conventions became more pronounced during the Great War (1914–1918), inspiring a particular brand of pulps highlighting the exploits of men in combat. During the mid to late 1920s, nearly fifty new pulp titles hit the market, dedicated in part or whole to war. Battle Stories, War Aces, and Under Fire all recounted stories of Yanks in the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), many written by veterans themselves, who interestingly tended to steer clear of heroic self-description.40 When young Americans went off to fight in the next world war, comic books, paperbacks, and magazines followed them across the globe, setting the stage for the postwar macho pulps. In one strand, comic books, like those featuring the heroic Flying Tigers, constructed the Japanese enemy as “dirty, buck-toothed … savages” who were little more than “rising sons of Satan.”41 In another strand, popular magazines like Esquire deployed images of sexually suggestive pin-up girls overseas to aid in the fight for freedom. Indeed, the US Army accorded Esquire special mailing privileges based on the magazine’s supposed ability to sustain GI morale. By war’s close, one could readily discern the links between war, masculinity, and sexuality in the most popular forms of reading materials.42

With the end of wartime paper quotas, and a ready-made market of primed readers, the popular fiction industry boomed. Postwar men’s adventure magazines, though, carved out a special place by consolidating rugged machismo, battlefield heroism, and over-the-top, aggressive heterosexuality into single tales. Scores of titles flooded newsstands – Saga (1947), Stag (1950), Man’s Conquest (1956), and Man’s Book (1962) to name but a few.43 At times referred to as “sweats” or “armpit magazines,” these newer versions of the classic pulps seemed a corrective to fears that American masculinity was under siege in a postwar, consumer-oriented society. Within their covers, stories of “real-life” adventures might remedy the boredom that was ostensibly gripping the thousands of suburban communities springing up across the United States. In fact, many of these pulps’ readers, like their World War I predecessors, were veterans not only trying to make sense of their wartime experiences, but seeking a return to the supposed glory days of their youth.44

How was a reader supposed to distinguish between such a glut of magazines? According to editor Bruce Friedman, a clear-cut hierarchy reigned in this genre. At the top stood True and Argosy, men’s true adventure magazines for the “hunting, beer, and poker set.” Next were titles published by the likes of Martin Goodman’s Magazine Management Company, the same house that would publish Marvel Comics. Here, one could find Stag, For Men Only, Man’s World, and Action for Men. On the lowest rungs, according to Friedman, were the “legions of other titles that generally featured Gestapo women prancing around captive Yanks in leg shackles.”45 If True and Argosy seemed more intended for middle-class men with disposable income – the quality of goods advertised suggested so – a clear misogyny still ran through all three tiers of these men’s magazines. Moreover, because most of these magazines were published in New York City, pulp stories and illustrations had to rely on the active imaginations of writers and artists who had little practical experience with the exotic locales they were portraying.46

Indeed, it was this very exoticism that drew many readers to the macho pulps. The stories were intended, in short, to stimulate. They attracted veterans returning from World War II or Korea seeking ties to a significant experience in their lives, perhaps countering the much-heralded “crisis of masculinity” that seemed so credible in the 1950s. They invited patriotic anti-communists who believed “effete” cosmopolitans were actively undermining the nation’s security. They drew in nervous traditionalists hoping to fight back against an onslaught of feminists apparently intent on usurping men’s roles as patriarchal leaders.47 They enticed teens seeking examples of what it meant to be a “real” man. And, in the early and mid 1960s, they appealed to men combating a sense of isolation from a changing culture in which old verities seemed to have lost public approval and support. As in earlier pulps, men’s adventure magazines spoke to the discontented man with an “infinite capacity for wishing.” And what better wish than to escape from the uncertainties of a rapidly changing postwar American society?48

Of course, readers of varying ages and socioeconomic positions likely consumed these magazines in different ways. One pulp writer believed the “average reader” to be “a mature man and an immature boy.” For the older reader, here was an opportunity “to escape into the literature of actions instead of ideas.” For the adolescent, however, pulps had the ability to influence “an immature mind which has not had, or has not profited by experience.”49 Thus, as boys were conceiving their future identities as men, the macho pulps boldly presented them with attractive images of “gritty action and tawdry sex.”50

If such popular depictions of masculinity now seem cheap and vulgar, it would be inappropriate to simply dismiss pulp writers as “penny-a-line scribblers.” True, many of their stories were mechanical and clichéd. One writer shared how he simply divided his tales into three natural parts: “characters, setting and problem; problem gets worse; problem still gets worse – and then is solved.” But behind the colorful heroes and dastardly villains were some notable authors, including Mario Puzo and Andy Rooney.51 Classic hard-boiled authors Mickey Spillane and Raymond Chandler also contributed the occasional murder mystery. And there were those well acquainted with war. Vietnam journalist Malcolm Browne penned combat stories, as did Robert F. Dorr, an Air Force veteran who would go on to complete a twenty-five-year career with the US Foreign Service.52

While battlefield exploits proved popular article entries, so too did the “hotsie-totsies.” In the early Cold War years, male consumers could find few sexual stimulants in popular culture, especially before the publication of Playboy in 1953. In fact, Hugh Hefner’s first choice for his new magazine’s title was Stag Party. Only after attorneys representing Stag magazine’s publisher complained did Hefner decide upon Playboy.53

Without question, Playboy was different than the macho pulps, intentionally so. From his Chicago office, Hefner wanted to offer something more refined than the “hairy-chested editorial emphasis” he found in adventure magazines. The ideal man who read Playboy was less about hunting and fishing and more about “inviting in a female for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.” Of course, Hefner’s supposedly progressive views, targeting the single middle-class consumer with an interest in sports, clothes, and liquor, conveniently obscured a gender hostility toward the very female bodies he was promoting.54 True, the women in Playboy were depicted more as girls next door than as sexual temptresses. Yet an editorial in the June 1953 issue suggested these women were not just the stuff of erotic fantasy, but of suburban, domestic oppression as well. “All woman wants is security. And she’s perfectly willing to crush man’s adventurous, freedom-loving spirit to get it.” The booming circulation numbers of Playboy verified that Hefner had tapped into the cultural zeitgeist of the early Cold War era.55

To be sure, however, only manly men graced the pages of the postwar pulps. Cavalcade, for example, advertised that its magazine contained “96 pages of real man’s reading,” while others, like Male, regularly included western yarns, literary spotlights on the rugged individualism so crucial to the narrative of American independence.56 Yet, not far below the surface, one could discern an uneasiness pervading men’s sense of social power. If masculinity, like gender, is a social construction, then in the 1950s and early 1960s, it also was a reaction to fears that passivity and femininity in an age of capitalist consumerism might be undermining traditional definitions of manhood. Take, for instance, the March 1960 Battle Cry article “Are You Yellow?” The story begins with World War II hero Audie Murphy fighting off elite Nazi troops before asking the reader if he can measure up to such feats of courage. After drawing upon psychological studies and historical examples, the author offers thin encouragement despite a confident tone: you, too, young reader can “make calls upon bravery no matter what your field of work, your age, or your place of residence.”57

As noted, that residence, for most pulp consumers, likely would have been found in America’s working-class neighborhoods. Both articles and advertisements catered to the “low brow” who, according to Life, drank beer, played craps, and spent time in his local lodge.58 Ads similarly indicated the targeting of working-class audiences. “Is there an ‘education barrier’ between you and promotion?” asked one company. “Are young college graduates being brought in to fill positions above you?” Other ads offered work clothes bargains, while still others promised that the “trained man” would have “no trouble passing the genius who hasn’t improved his talents.” Indeed, advanced education was hardly a guarantee of success. “You don’t need a college diploma but you do need plenty of common sense and you’ve got to like people,” trumpeted one personality self-help advertisement.59

More than a few blue-collar Vietnam veterans recalled growing up and being intrigued by their fathers’ war stories that were a mainstay of these macho pulps. “It seemed so exciting and exotic,” one infantryman remembered. And yet despite wartime evidence of class inequities in draft policies, the adventure mags pushed back against any perceived injustices. Veteran Micheal Clodfelter noted that the men “with whom I shared the Vietnam War were overwhelmingly the sons of steelworkers, truck drivers, mechanics, small farmers and sharecroppers, men from small towns and rural routes in the South and Midwest or from big city ghettoes.”60 A Stag offering from July 1966, however, argued that men like Clodfelter were mistaken and the army was “almost a perfect cross-section of U.S. population, with people from every walk of life in just about the same proportion as they are in civilian population.”61

Perhaps because of adventure magazines’ popularity among veterans and in working-class neighborhoods, they also were rabidly patriotic. Pulp writers did not simply defend Cold War policies, they trumpeted nationalism through a military lens, often decrying America’s weak-kneed response to the glaring threat of communism. In a precursor to Vietnam-era criticisms of civilian interference in military affairs, one author asked why the Pentagon was “keeping handcuffs on our jet fighters” in the skies over East Germany.62 Another, deriding US social policies overseas, demanded “It’s Time for America to Get Tough!” In many ways, a sense of militarized masculinity thus became embedded into the nationalist rhetoric emblazoned on the pages of the pulps.63

Such a linking should not surprise. In large part, ideas about power stood at the core of conceptualizations on both nationalism and masculinity. After all, gender – of which masculinity is a part – is as much a political system as a symbolic one. The macho pulps clearly illustrated a preference for male social domination, one that could be extrapolated outward to Cold War America.64 Manly adventure stories within these magazines symbolized an idealized gender structure that no doubt resonated with many male readers. Here, historian Joan Scott’s definition of gender seems most useful. To Scott, gender is a “primary way of signifying relationships of power.” How pulp readers viewed and went on to enact their understandings of gender and masculinity in Vietnam will become an important part of this story.65

Of course, these magazines competed with other forms of popular culture, such as comics and television, offering a wide range of popular masculine images. By the end of 1952, there were more than nineteen million television sets in American households. Young and old alike could watch heroic gunslingers in scores of westerns, either on TV or in local movie theaters.66 And, perhaps just as importantly, young readers doubtlessly compared the pulps’ “true adventures” with tales they heard from World War II and Korea veterans who were family and friends, even if those vets might be reticent to share the more unpleasant aspects of their wartime experiences. Yet, despite the fact that several vying mediums were competing for audiences, the circulation of all magazines increased by more than twenty percent between 1950 and 1960. Television may have been seeping into the “nation’s bloodstream,” but the publishing industry was still clearly holding its own.67

Without question, assessing how a masculine ethos and its values are carried on to younger generations defies precision. Yet men’s adventure magazines clearly evinced an established male culture that relied heavily on patriarchal notions of society. And it did so in a fashion that was both compelling and alluring, since the stories highlighted both war and sex. At least some part of this philosophy was transmitted to, and internalized by, the Vietnam draft generation.68 Surely, marine veteran Philip Caputo wasn’t alone in sharing that “the heroic experience I sought was war; war, the ultimate adventure; war, the ordinary man’s most convenient means of escaping from the ordinary.” It seems probable that certain key aspects of adventure magazines became embedded in male culture, socializing young men how to think about war and women. In this way, magazines were one manifestation of popular culture shaping broader Cold War stereotypes and public opinions.69

By the early 1970s, men’s adventure magazines had fallen out of favor, ultimately left behind by a generation willing to reject many of their elders’ traditional cultural assumptions. But it was the war in Vietnam that rang the macho pulps’ death knell. The long, unsatisfying conflict had yielded few heroes, leaving little incentive for readers to view military service as a rite of passage to manhood.70 A decade earlier, though, as Americans went off to war in Southeast Asia, the elements of male culture depicted in adventure magazines were clearly identifiable in the language of those slogging their way through the rice paddies and jungles of Vietnam. As one war correspondent shared, “Young men court danger as they court women, and for much the same reasons … secretly each wants to be a hero, in the finest and best sense of the word, and there’s nothing wrong with that, because quiet heroism is the stuff of war.”71 Or so young boys were told in Cold War America.

Militarizing Manhood

“We are a nation at war,” boomed Pennsylvania State Senator Albert R. Pechan in 1953. Never mind that World War II had ended almost a decade earlier, or that the fighting on the Korean peninsula was coming to a close. For Pechan, the distinction between war fronts and home fronts made little sense in this new era. “The force that is killing our loved ones, the power that is fighting against our democracy, is Communist, Godless Russia. It is fantastic,” Pechan argued, “to fight Communism with all our strength abroad and to ignore it at home.”72

By 1953, the nascent ideas of persistent war and a national security state in constant need of maintenance were taking hold in communities across America. Everywhere Americans turned, they saw an international crisis – in Korea, Chile, Algeria, Iran, and Indochina to name but a few. Worse, clandestine communist forces and Soviet spies seemed to lurk behind every corner right here at home. The very idea of peace seemed dangerous. Though the public might recoil at the thought of an American empire, surely a robust, global military machine was necessary to keep these evil forces at bay.73

This inability to fully demobilize after World War II led to vast increases in defense spending, the re-installment of a peacetime draft, and the notion of continuous “wartime” mobilization. The outbreak of fighting in Korea in July 1950 only reified worries that global communists were on the march. In the process, conceptions of military service, citizenship, and masculinity all became tightly intertwined.74 The February 1953 issue of American Manhood, for instance, offered advice on the prospects of a military career. Being drafted could “pay off big dividends,” as “you can come out a far better man than when you entered the armed forces.” Four years later, Saga was extolling the men of the US Air Force’s Strategic Air Command (SAC) as “real pros” who were members of an “elite corps. If there was ever a more self-confident outfit in military service, history does not record it.”75

Fig. I.4 American Manhood, January 1953

Such applause proved useful for US military leaders who, competing with civilian businesses for talent, needed to retain young men’s attraction to war. Selling the “soldier” as the best venue for becoming a “man” clearly helped with recruiting efforts. And while the macho pulps were far from a government mouthpiece, they nonetheless were energetic promoters of the armed forces. “You’re a Marine,” declared one article, “then mister, you’re a man. There’s no two ways about it.” To uphold the traditions of the Marine Corps’ “brilliant service” to the country took “a lot of man.” Another on marine boot camp claimed that when a recruit completed his training, “he knows he’s proved himself a first-rate fighting man.”76 A full decade later, such storylines had hardly changed. “Combat commanders in Viet Nam,” Male declared in 1967, “are sending back reports that younger men still make the best fighters – that means 18–20 in age.”77

So too could social critics exploit the macho pulps’ depiction of masculinity which, to them, was under assault from overprotective mothers. This threat of “momism” suggested to commentators like Myron Brenton that an overinvolved mother might “devour her sons emotionally,” leading to “mama’s boys,” an epidemic of homosexual children, and, ultimately, a feminized society. As early as 1945, Ladies’ Home Journal had published an article asking “Are American Moms a Menace?”78 Luckily, postwar men’s magazines offered an answer. If the mother could not teach her son to be a man, then the armed forces would. Take, for instance, a Stag “confidential” from March 1966. “Lots of mothers who cry ‘hardship’ when their sons are being drafted are actually interested in smother-loving the son to death than in protecting him. Draft Board is actually doing these boys a favor by putting them in uniform.” That child rearing and national security remained so interconnected for so long surely implies deep anxieties about gender conceptions in the Cold War era.79

Given the weighty implications of defining the military as a wellspring of American masculinity, what better way to attract men to war than by linking it to sexual rewards? Here the macho pulps enhanced the myth-making power of cultural stories by claiming that women were naturally attracted to men in uniform. Adventure magazines were rife with tales of the military man’s sexual virility and exploits, such as when American Manhood told readers that the US Air Force not only offered “unlimited career opportunities,” but the cut of a uniform “with its attractiveness to the opposite sex.”80

This conflation of military and sexual power was on full display on pulps’ cover images, which regularly displayed courageous men dealing with danger, overcoming adversity, and usually winning sexual rewards for their heroics. The cover for the October 1957 issue of Battle Cry flaunted several GIs being kissed by Parisian women, offering chocolate to a small child, and astride a tank firing at an unseen enemy. Rifles unsubtly protruded in all their phallic grandeur. A story in Big Adventure described postwar Parisian girls – “thousands of them” – as “literally fighting each other off in an attempt to capture the GI’s interest.” In this way, according to historian Mary Louise Roberts, the American knight could be “duly awarded” for protecting not only the French nation, but its women as well.81

The pulps’ flattering representations of the American soldier allowed civilians (and noncombat veterans) to live vicariously through warriors’ experiences, to read stories where anyone could be a hero. For boys of the “boomer” generation, many of whom admired their fathers’ triumphant return from World War II, magazines helped validate a concept of manliness embedded in martial valor. In the process, according to one military psychiatrist, masculinity became “an essential measure of capability,” wherein “the maleness of an act is the measure of its worth and thus a measure of one’s ability.”82 Nowhere were masculine acts more viscerally portrayed than in the macho pulps. They offered a world where young men could assert their manhood by defeating the enemy.83

In feting these American heroes, adventure stories clearly oversimplified, crafting a reductive narrative of good versus evil that was readily transferable to and consumed by their readers. Here were villains easy to understand. In the pulps, only the Nazis or “commies” – “the Red legions” according to Saga – were interested in taking over the world. And even if racialized enemy foes, like the Japanese, were “worthy of hate,” they did not reach the level of condemnation reserved for Hitler’s murderers or communist sympathizers. In a pinch, Nazis always could serve as a pulp writer’s villainous nemesis.84 Thus, throughout the Cold War, Nazi henchmen, “merely following orders” in their prosecution of mass murder, easily could be contrasted to the just American warriors defending against the red hordes in far-off places like Korea.85

Such a simplified version of the enemy would have severe ramifications when young men were exposed to a much more complicated enemy situation in South Vietnam. The fighting there, in one accounting, tended to render World War II “heroism unattainable.” Surely, the depictions within adventure magazines were neither completely manipulative nor fully authentic.86 Yet the storylines just as surely painted a world view in which the United States was a bastion of freedom defending against the evils of a barbarous, godless communism. It is plausible that such simplistic renderings helped persuade more than a few young Americans off to war in the early to mid 1950s. As historian Christian Appy has argued, the boys “who would be sent to fight a war of counterinsurgency in Vietnam grew up fighting an imaginary version of World War II.” Many would be sorely disappointed that reality hardly matched the pulp magazines’ fantasies.87

And yet we – like those young men – want certain narrative arcs when it comes to war. We are inspired by stories of young men’s perseverance in combat, of their ability to withstand both imprisonment and even abuse. We are heartened by tales linking national will and security to the resolve of hearty individuals willing to sacrifice for the greater good. And, in the same vein, we are disappointed when soldiers, like one Vietnam veteran, return home and share that they “felt it was all so futile.” In short, we want to find meaning in war, a sense of purpose that makes us feel better about ourselves and our nation.88

Indeed, the very success of the macho pulps rested upon the notion that real men still mattered, both at home and abroad. And these adventure magazines not only adopted models of contemporary gender differences, but exploited the fantasy that battlefield heroism legitimized sexual conquest. One army medical corps physician suggested as much as the conflict in Vietnam was coming to a close for weary Americans. To him, war historically had conferred upon soldiers “complete sexual license,” with sex itself often viewed as an “allowable excess of battle and particularly a reward for victory.”89 Pulp writers couldn’t have agreed more.

War as Sexual Conquest

John Wayne may have been the epitome of the postwar generation’s “manly man,” but we tend to forget that throughout his movie career, the “Duke” largely remained an asexual figure.90 Post-World War II men’s adventure magazines, however, departed from such chaste depictions, instead constructing the “noble” warrior as a sexually charged male seeking release and reward. And perhaps here, the pulps, in a narrow sense, accorded more with reality. Both military commanders and GIs of the era worried about sexual deprivation on the battlefield. Indeed, one senior US officer held that “male sexual activity was healthy for battle.”91 Soldiers imparted similar beliefs. War, popular notions held, seemed to increase the GI’s sexual appetite. What better place to satiate these cravings than in a combat zone? As one American soldier serving in Europe noted, war “offers us an opportunity to return to nature and to look upon every member of the opposite sex as a possible conquest, to be wooed or forced.”92

The covers and artwork of men’s adventure magazines purposefully exploited these convictions, intertwining war and sex in enticing images that might draw hungry eyes to newsstands. The cover for the September 1957 issue of Man’s World, for example, shows a tough GI straddling a .50 caliber machine gun, its barrel jutting out toward the reader while spewing bullets. Next to the soldier, in bold white letters, is a teaser for one of the articles inside, “Sex Life of the American Woman.” (Rifles and machine guns as phallic stand-ins seemed an artistic requirement.) One Battle Cry illustration depicted an American GI evading Nazis through a burning European village. His M1 Garand extends out from his waist, while a local red-headed woman – with bright red lips and a low-cut white top – stands behind the American, her hand gently resting near his trigger finger.93

The rhetoric of these gendered images suggested a hardening of the post-World War II patriarchal structure. In the pulps, women were to be subservient in American society. Take, for instance, one All Man article targeting “sex shy men,” which offered advice on how to “make every woman your slave.” Surely, such articles predisposed men toward seeing sexual conquest in war as the norm.94 Veteran J. Glenn Gray spoke in similar terms. In his World War II memoir, Gray argued that for the “sensualist as soldier,” war was a “convenient opportunity for new and wider fields of erotic conquest.”95 Might it be that young soldiers in Vietnam reading articles about forced sexual conquest of enemy women believed that such behavior was well within the normal boundaries of war?

It must be emphasized, and strongly, that reading men’s adventure magazines did not result in a chemical reaction ensuring America’s youth would mindlessly commit sexual violence overseas. Yet, if the articles were not prescriptive, they still normalized or at least familiarized a certain type of behavior in their storylines and opened up a narrative space for what some American soldiers deemed acceptable in their contacts with the Vietnamese population.96 One Vietnam-era offering highlights how popular culture may well support sexual violence. In September 1966, Male ran an exclusive that clearly promoted rape. “Many women, young ones in particular, are ‘sexually reversed’ in their actions, that is whatever they say can be taken to mean the opposite. ‘I absolutely don’t want to sleep with you’ for example, means precisely the opposite.”97

If, in Vietnam, adventure stories ranked among the “most widely read literature among the guys,” then it is worthwhile to assess how they connected militarized masculinity to sexual conquest by force. Without question, cultural products like the macho pulps were read in diverse ways, often unanticipated by their authors.”98 Individuals make sense of images and texts differently. Still, these magazines embraced misogyny in their portrayals of American soldiers and their place in wartime societies and, as such, may have primed aggressive behavior once those soldiers arrived in South Vietnam. Given their alluring artwork and persuasive stories, adventure magazines resonated with young Americans seeking validation of their manhood in the early and mid 1960s. For some, the fantasy must have been irresistible. And, in far too many ways, utterly disappointing.99

In the chapters that follow, we will witness deeply disturbing images and storylines that appeared in the pulps and search for links between GIs’ frustrations over the reality of combat in Vietnam and the messages espoused by such cultural products. Our exploration will begin by placing men’s adventure magazines within their Cold War context before examining how they constructed a version of World War II and Korea that depicted heroic men as warriors, protectors, and sexual conquerors. The narrative then moves to the macho pulps’ portrayal of women, especially non-European, non-white women, and suggests that such representations left young male readers with the impression that American dominance overseas allowed them to engage in a form of sexual oppression there. We end in Southeast Asia, comparing the fantasy of war as depicted in the magazines with the reality of Vietnam, considering ways in which the pulps contributed to a culture which found it acceptable to engage in violence against the Vietnamese population, especially its women.

Several studies have identified a relationship between aggression levels in previously angered men and an exposure to pornographic images.100 In a similar way, I suggest that men’s adventure magazines fostered an implicit consent of sexual subjugation by defining militarized masculinity as embodied in both the battlefield hero and the sexual conqueror. For some, theory became practice, violence a sort of male wish-fulfillment already whetted by Cold War culture. As one veteran laconically recalled, in war, GIs and women were “almost always the two main classes of people getting fucked.”101

With this in mind, Pulp Vietnam should be read as a purposeful melding of popular cultural, social, and military history, one that asks serious questions about the connections between these three fields. How much of sexual conquest is part of war in general and how much is due to a particular set of historical circumstances? How widespread and influential were images of American warriors that equated military masculinity to the sexual domination of women? And how, in the end, do we measure the cultural and individual impacts of men’s adventure magazines, their power to reinforce certain ideas about Cold War manhood that may have reaped horrific rewards on the battlefields of Southeast Asia?102