Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: ‘Representation’ and Medieval Mediations of Violence

- Part I The Ethics and Aesthetics of Depicting War and Violence

- Part II Debating and Narrating Violence

- 4 ‘With face pale’: Melancholy Violence in John Lydgate's Troy and Thebes

- 5 ‘In Praise of Peace’ in Late Medieval England

- 6 Representing Political Violence in La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei

- Part III Experiencing, Representing and Remembering Violence

- Bibliography

- Index

6 - Representing Political Violence in La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei

from Part II - Debating and Narrating Violence

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2016

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: ‘Representation’ and Medieval Mediations of Violence

- Part I The Ethics and Aesthetics of Depicting War and Violence

- Part II Debating and Narrating Violence

- 4 ‘With face pale’: Melancholy Violence in John Lydgate's Troy and Thebes

- 5 ‘In Praise of Peace’ in Late Medieval England

- 6 Representing Political Violence in La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei

- Part III Experiencing, Representing and Remembering Violence

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

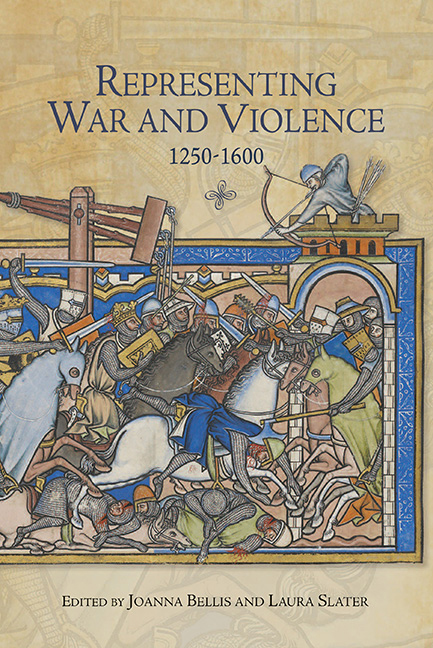

War and violence are routinely represented in illustrated hagiography. Crowded battle scenes and images of combat can depict holy war, civil conflict in the aftermath of conversions and various external threats to Christians. Yet most visual representations centre on the figure of the Christian martyr. He or she is conventionally shown as a still and serene witness to Christian truth, enduring pain with balletic grace and beauty in contrast to the frenzied reactions of the persecutors and spectators surrounding him/her. Frozen at the moment of death or torture, ordinary time is suspended. Each image of suffering hangs between the ‘palpable boundaries of memory and geography’ that characterise historical time, and the unfolding eternity of liturgical time and devotional remembrance. In contrast to textual accounts, cumulatively experienced as the sentences build up and the literary imagery develops, the visual record can be viewed in a single, arresting instant, even if this is followed by more extended visual contemplation. Recent scholarly focus on the erotic qualities of such images only underscores their deliberately paradoxical character. Apparent images of humiliation and abjection were scenes of triumph once read with the eye of faith. The exposed, disfigured and destroyed body of the martyr was in fact shown at the moment of its salvific remaking: shame became sublime, corpse became relic and death became eternal life.

As others in this volume have explored, aestheticising pain and suffering was a normative part of authorial and artistic efforts at conversio morum, and there is little to suggest that patrons or artists found the phenomenon troubling. It was axiomatic that exterior physical beauty reflected inner spiritual purity and could be harnessed as a stimulus to devotion. Aristotle's observation in the Poetics that ‘we enjoy contemplating the most precise images of things whose actual sight is painful to us’ did not circulate in meaningful form in Europe, but medieval audiences were certainly encouraged to imagine the Passion of Christ stage by stage and in intense, emotive and almost inventorial detail.

This article focuses on the representations of war and violence found in a masterpiece of English illustrated hagiography. In the late 1230s, the Benedictine monk, artist and historian Matthew Paris composed an illustrated life of St Edward the Confessor, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Representing War and Violence, 1250-1600 , pp. 116 - 136Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2016