Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: ‘Representation’ and Medieval Mediations of Violence

- Part I The Ethics and Aesthetics of Depicting War and Violence

- Part II Debating and Narrating Violence

- 4 ‘With face pale’: Melancholy Violence in John Lydgate's Troy and Thebes

- 5 ‘In Praise of Peace’ in Late Medieval England

- 6 Representing Political Violence in La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei

- Part III Experiencing, Representing and Remembering Violence

- Bibliography

- Index

4 - ‘With face pale’: Melancholy Violence in John Lydgate's Troy and Thebes

from Part II - Debating and Narrating Violence

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2016

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: ‘Representation’ and Medieval Mediations of Violence

- Part I The Ethics and Aesthetics of Depicting War and Violence

- Part II Debating and Narrating Violence

- 4 ‘With face pale’: Melancholy Violence in John Lydgate's Troy and Thebes

- 5 ‘In Praise of Peace’ in Late Medieval England

- 6 Representing Political Violence in La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei

- Part III Experiencing, Representing and Remembering Violence

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Sourcing war / voicing war

John Lydgate, monk of Bury St Edmunds, is the premier learned war poet of the later English Middle Ages. His Troy Book (written 1412–20) is a translation and vigorous adaptation of Guido delle Colonne's thirteenth-century Historia Destructionis Troiae. The nature of the Troy Book's literary influences is complex, since Guido had claimed that his Trojan story was based on the ‘eyewitness’ accounts of Dares Phrygius and Dictys Cretensis, but in reality it was derived mainly from Benoît de Sainte-Maure's Roman de Troie (c. 1155). The Troy Book also shows familiarity with Statius's blood-soaked epic Thebaid (c. 91), which is cited at length in Lydgate's Prologue as a shining example of how poets preserve the memory of famous wars. Lydgate's subsequent Siege of Thebes (c. 1421–2) draws on earlier medieval versions such as the Roman de Edipus and the Histoire Ancienne Jusqu’à César, but also shows the influence of Statius. In writing these wars, the English poet was therefore involved with a long history of Latin writing on Troy and Thebes, as well as the medieval French roman antique and the work of his great English predecessor Chaucer, especially Troilus and Criseyde (c. 1385). Lydgate's order of composition – Troy then Thebes – goes against historical chronology, but he keeps both wars in mind from the start. He makes the Thebes story first a precursor to Troy, then an opportunity to revisit the Troy Book's concern with the grim nature of war, especially through a continuing dialogue with Statius. In both accounts, Lydgate is preoccupied with the responsibility of the writer in accurately describing these conflicts to future times, and stresses both their enduring fame and their appalling violence.

Sylvia Federico has shown how important in late fourteenth-century and fifteenth-century England was ‘[t]he right to wield … [the] precedent’ of Troy, ‘to reground and rejustify political motive in relation to an imagined antiquity’. The Lydgate of the Troy Book has been seen as a propagandist, legitimating himself as Chaucer's successor, and boosting English vernacular poetry and historiography as he legitimates Lancastrian ambitions: the poem was dedicated at the outset to Prince Henry, who had long been King Henry V by the time it was finished. It has been seen as imperialist: ‘[i]n translating Guido's Troy for Henry V, Lydgate attempted to revive Troy's empire for Britain’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

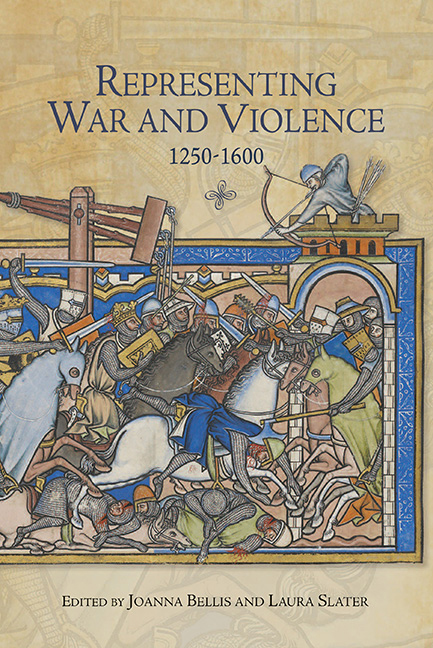

- Representing War and Violence, 1250-1600 , pp. 79 - 94Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2016