Introduction

Across the world, minority languages have been under pressure from regional, national, or global languages as these larger tongues became associated with greater social, cultural, economic, and political opportunities compared to local languages. This was particularly true during the period of European colonization and has accelerated in the last seventy years with the rise of independent nations from the colonies, and the spread of national and global languages through government, education, workplaces, service contexts, media, and the Internet. As a consequence, and because of negative attitudes towards them, minority languages have become endangered as they are no longer learned by children.

One response by linguistic researchers to these threats to minority languages has been the development of a way of researching languages and their use that has come to be called ‘language documentation’. In this chapter, I explore what documentation is, whether and how the outcomes of documentation can be used for revitalization (which aims to increase the domains and numbers of speakers of threatened languages), and some of the limitations and challenges of working with language documentation materials. I end by discussing some possible opportunities for documentation to be more creatively used both for and with revitalization.Footnote 1

What Is Language Documentation?

In about 1995, a new approach to studying languages around the world was developed that has come to be known as ‘language documentation’ or ‘documentary linguistics’. This approach aims to create audio-visual samples of language use and performances, ranging from everyday conversations to narratives (story telling) to more ritualized activities such as prayers, ceremonies, and recitations. The idea is to create an organized collection (called a ‘corpus’) of examples of the use of the language in their social and cultural contexts. The outputs from language documentation are intended to be a multipurpose record that could give an idea of how a language is actually employed in a range of contexts and situations by a range of speakers (e.g. male, female, old, young). These records could then be used by both current and future speakers and learners as resources to support the minority language, e.g. in mother-tongue education, or to increase its social status, and for learning or re-learning the language, and thereby revitalize it (I discuss the relationship between documentation and revitalization in more detail below). To this end, language documenters emphasize that a copy of the corpus should be placed in an archive, along with relevant metadata (information about the information in the corpus) such as the names and ages of speakers, where the recordings were made, who collected them etc. Later I discuss what I mean by archiving and some of the challenges it entails.

Just like researchers who create nature documentaries, language documenters frequently work as a team and emphasize the importance of making high-quality audio and video recordings in their environmental, social, and cultural contexts, ideally in the locations where the people who speak the language live. This typically involves fieldwork and participant observation, where speakers are recorded using the language in their daily life, with their informed consent and following proper ethical consultation. Such work is best carried out by a documentation team which ideally includes local researchers and/or assistants who can contribute their knowledge and skills to the documentation and its local impact. In the process, the documentary team will learn about the structures and organization of the languages used in the community and how they function, especially the different domains that different languages or ways of speaking are employed in. They can also study the attitudes and beliefs that people have towards the various languages they know, and how they are used. There may also be interviews with speakers, asking them to translate from their languages into a language of wider communication (a lingua franca) or vice versa, or checking words and sentence constructions (grammar), or the social and cultural significance of different ways of speaking. The corpus would typically contain transcriptions of the audio-visual recordings (which sometimes involves creating a script or writing system for unwritten languages), and translations into a language of wider communication so that it can be accessed by people who do not speak the languages being documented. In addition, explanatory notes or information about words, grammatical structures, and uses may be included in the corpus, along with information about the records in the corpus, called metadata (who is speaking, when, where, why, etc.). This is needed for records in the corpus to be findable, and for the audio-visual collection to be maximally useful, especially for language learners or those who partially speak the language or do not know it at all.

Language documentation can be distinguished from language description, which is the study of the structure of languages, looking at their pronunciation (phonology), word structure (morphology), sentence structure (syntax), and how meaning is expressed (semantics and pragmatics). In language description researchers aim to identify the significant parts of languages and how they work together in a structured way, typically producing grammatical descriptions (or grammars) that explain how the language is organized. Language description also often involves cross-linguistic comparisons to identify properties that are rare, unusual, or common among the languages of the world. Language descriptions can be based on a language documentation corpus, but they do not have to be. They can be produced by studying words and meanings in isolation, especially where the description is based on the author’s own language and their own intuitions about how it is structured. Note that description and documentation are different but related activities: Language documentation must include a certain amount of language description in order to create the transcriptions and translations and other metadata that are an essential component of the corpus, linked to the audio-visual recordings. Without description, documentation is difficult, if not impossible, to access and use. I discuss the relationship between documentation, description, and revitalization further below.

For some languages, there may be audio or video recordings, written records, and descriptions that date from some time ago. They may have been collected by explorers, colonists, missionaries, or interested amateurs who lived in or passed through the region and learnt something of the language. We can refer to these as ‘legacy materials’, a term that can also be used for written or audio-visual materials that were collected by other people and passed on to another (typically later) research team, including those working on revitalization or language support. These legacy materials present particular challenges if we wish to include them in the documentary corpus and/or use them for description and revitalization – I discuss these challenges later.

The Relationship between Documentation and Revitalization

Language documenters often say that one of their goals in creating their corpus is to make it available for use in language revitalization. However language documentation corpuses may not be ideal or even useful for the purposes of language revitalization.Footnote 2 There are several reasons for this:

(1) The records in the corpus may focus on interesting or unusual linguistic features rather than how conversations are organized in the particular community (how we begin, end, or change and interrupt a conversation varies from language to language), how to use language to get people to do things, what is appropriate to say or not say in what situation, how to agree, disagree, or argue with someone, and how to be a functioning speaker of the language;

(2) Conversations, narratives, and interviews may focus on the past, looking back nostalgically to the ‘good old days’ before social, cultural, and linguistic shifts began to take place, often highlighting the childhood or early adulthood of the current oldest generations of speakers. This may be accompanied by negative evaluations by those speakers of the changes that have taken place, with a sense of ‘loss’ or ‘corruption’ of older ways of speaking and thinking. Such materials and attitudes can be off-putting for children and young learners, and those who wish to see a positive image for the future of the languages;

(3) The linguistic analyses created by language documenters, including transcriptions and grammatical annotations, may be produced in orthographies or languages unknown to the community and using specialized terminology which is not easily understandable to non-linguists;

(4) The language practices included in a corpus may not match the perceptions or preferences of teachers and language activists, especially when there is evidence of language shift in the form of language switching, borrowing or mixing, and variation and change. Revitalizers may prefer purism when creating learning materials, rather than using the documentary resources. There can be tensions between teaching ways of speaking or structures based on the usage of traditional native speakers (usually ‘elders’) documented in the corpus versus those of younger or ‘new’ speakers, especially for languages where there is no established standard form;

(5) Because researchers often aim to capture usage by ‘the best speakers’, the resulting recordings may be difficult to use for revitalization because they are heavily biased towards older people who speak fast, mumble, slur, or elide their utterances, or even have speech impediments (including lack of teeth) or are hard of hearing. Fluent speakers may also rely heavily on background knowledge or history of the people and places involved that might not be clear or obvious from the conversation or story. Such material can be difficult for learners, especially at an early stage, to understand, process, or model;

(6) Documenters rarely record speech directed towards children and language learners so the corpus may tell us nothing about how to speak to them. Missing may be such things as lullabies, children’s games or rhymes, jokes, or simple exchanges or routines that would be useful for an early or intermediate learner to acquire;

(7) The conversations or narratives in the corpus may include topics such as secret or sacred practices, death, or sexual relationships, swearing or impolite expressions, or gossip, which are not appropriate for language learners, especially children.

For these reasons, materials in a documentary corpus might be useful for revitalization, but they must be approached with care, and the attitudes and reactions of speakers and learners of all types need to be taken into account. It is often a difficult balancing act to use documentary and descriptive materials for revitalization purposes, and in some cases it may be that documentary corpuses or descriptive grammars and dictionaries are of very little use for language learning and revitalization. Later I suggest some ways that documenters can make their current and future work more useful for these purposes.

Working with Legacy Materials

In some situations, especially for areas that were colonized in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, there may be few or no contemporary speakers of the languages, and the main resources available for revitalization are written wordlists, texts, translations, or old recordings (on tapes or cassettes) collected by explorers, missionaries, or settlers. Sometimes we find notes and letters written by speakers themselves who were writing in their own languages to express their thoughts and feelings, to communicate with colonial or missionary authorities about legal, cultural, educational, and economic matters, or to preserve threatened knowledge, like stories or vocabulary. This is true in areas such as eastern Australia, the north-east coast of the USA, Mexico, or southern South Africa. Occasionally we may also find written records or audio-visual recordings made in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries by professional linguists that have been preserved (sometimes after the person has died) in private collections or libraries and archives. We can refer to all of this as ‘legacy material’, and for some communities, such as the Kaurna people of Adelaide, Australia,Footnote 3 it has proven to be extremely valuable and a major source for language revitalization and re-learning (see Capsule 1.4 on reading historical texts in Nahuatl). Legacy materials may present opportunities for being adapted for use in revitalization, and may be a great source of information about languages and social and cultural practices that are only dimly remembered or have gone out of use. They can be a source of idioms, metaphors, and sayings that are no longer known, as a result of the impact of the dominant languages. They can also provide valuable insights into how languages can adapt to changing circumstances to create new words or expressions (called ‘neologisms’). For example, in missionary Bible translations for Diyari, spoken in South Australia, we find the verb dakarna, which originally meant ‘to stab with a pointed instrument’ (like a spear or stone knife), was extended by the missionaries to mean ‘to write’ (with a pen or pencil). This might be further extended to mean ‘to type on a keyboard’ (of a computer or mobile device) since we now use our fingers as pointed instruments to do this.

However legacy texts and recordings can also present special challenges, and must be approached carefully. It may require specialist help from librarians, technicians, historians, or linguists to make sense of the legacy materials and to make them maximally useful, for the following reasons:

(1) Ethical and political issues – often it is unclear how the legacy materials were collected and whether the collectors had permission to distribute them to others or were given instructions about how they could be used. If the collector is alive we can ask about this, but frequently this may not be possible. Sometimes there are living descendants of the collector and/or the people whose languages and cultures are recorded (including particular individuals if their names are known from the sources) and there may be complex issues about ownership of and rights to the knowledge and intellectual property contained in them. This needs to be discussed properly and openly when approaching older records, and may require legal advice in difficult situations;

(2) Form and content issues – the legacy materials may be written in an obsolete or obscure writing system, or spelled in an inconsistent or inaccurate way that does not properly represent the pronunciation, structure, or use of the language. If there are translations, they may be unclear, incomplete, or wrong. Sometimes we may need to do detective work, cross-checking different sources to ascertain what particular forms or meanings are intended, or to compare them to information about neighbouring and/or related languages to search for clues. In some instances, it may not be possible to decide, and a given spelling, translation, or expression has to remain ambiguous or unknown. Old sound and video recordings (on tapes or cassettes) may be affected by wear-and-tear (including mould or tape degradation, or stretching) and it can be difficult nowadays to find equipment that will play them so that they can be copied and digitized. It is best to seek professional advice from librarians, archivists, or media specialists (including radio and television organizations) before taking on the task of using such recordings for revitalization. Also, old digital files (on floppy disks or other storage devices) may need to be converted if the fonts and software used to create them are now obsolete. In the worst case, some old computer files may simply be unreadable and hence unusable;

(3) Context issues – for legacy materials that include stories or songs, we may not have information about who the audience is intended to be, or on what occasions they can be told or sung (e.g. is it a story for children or a sacred myth only to be shared with older people, or perhaps only with men? Is it a ribald song not meant for young people?). A community’s social, cultural, or religious beliefs may also have changed over time so that certain older materials are no longer considered appropriate for public performances, especially for younger people or those outside a given group. Sometimes collectors can make remarks or comments in the materials, or use words and expressions that were common at the time of writing or recording but would now be considered to be inappropriate, racist, or sexist (and perhaps were never intended for public consumption anyway). There may also be references to people, places, or things that are obscure, or only known to certain individuals or groups. This means we need to take care when thinking about how such materials might be employed in revitalization, and seek advice from relevant knowledge holders if possible.

In summary, legacy materials can be very valuable sources of information about languages and cultures for use in revitalization and recovery of knowledge and practices, but they need to be approached circumspectly and used appropriately. It is advisable to seek professional advice and training when necessary.

Working with Archives

An archive is a trusted repository set-up to collect and preserve historical materials of a certain type. Archives can be analogue (collecting physical objects like letters, notes, books, photographs, or video and audio tapes) or digital (collecting computer files of various types, including photographs or scans of physical objects), or a mixture of both. All archives have a collection policy that sets out the types of things they are interested in. For material on languages and cultures, there are several types, which differ in their resources, staffing, coverage, and interests:

(1) National archives like the British Library, British Museum, Library of Congress, Smithsonian Institution, National Archives of Australia etc.;

(2) Regional archives like the Alaska Native Language Centre (ANLA), Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America (AILLA), California Language Archive, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) etc.;

(3) Local archives like those of the boroughs of London, the Dialekt-, ortnamns och folkminnesarkivet i Umeå Department of Dialectology, Onomastics and Folklore Research in Umeå, Sweden, etc.;

(4) Professional institution archives like the American Philosophical Society, Royal Anthropological Institute, or collections that are housed within university libraries.

Individuals may have personal collections of materials or objects they have amassed over many years, but we do not normally consider these to be an archive as they do not usually have an explicit collection policy, a publicly accessible catalogue, or institutional backing for long-term preservation and sustainability. There is a useful listing of digital language archives that collect documentary and descriptive materials for endangered languages on the website of the Digital Endangered Languages and Musics Archives Network (DELAMAN).Footnote 4

Archives can be important sources of information on languages and cultures (both tangible and intangible cultural heritage) that can be valuable for language revitalization, though it often takes some work and efforts to track down and identify what materials are held where.Footnote 5 Above I have identified issues and challenges with making use of legacy materials that may be stored in an archive, but in addition to these there can be particular matters relating to using archives themselves, especially digital language archives:

(1) Archives will have a usage and access policy that sets out who may use the materials in the archive (everyone, or certain types of people only), and how they may be used (read or listen to only, copy but not distribute to others, or freely copy and distribute). Sometimes it is necessary to pay for access (e.g. to receive a digital copy of a document or recording). In some archives, especially wholly digital ones, access may require permission from the person or group who deposited the corpus, folder, or individual file that the user is interested in;

(2) The archive may contain materials on a language you are interested in but list it under a name which is not the one used in the community (it may even be an outdated or insulting term dating back to colonial times or legacy materials). You may need to try various spellings of the language name when searching in the archive catalogue listing;

(3) The archive catalogue may be complicated or difficult to use, even if it is available online, and might be only accessible in a language that is not widely known to the speech community. For example, most DELAMAN archives mentioned above have catalogues in English only. AILLA, which focuses on Latin America, does have its catalogue in Spanish and English, but not in Portuguese (for users in Brazil), or in any minority regional language, such as Guarani or Quechua, both of which have millions of speakers and active research and revitalization communities;

(4) Deposits in archives may be incomplete, or in the case of digital archives in particular, only partial or inconsistent. It is frequently the case that researchers working on minority languages deposit their corpuses incrementally as their documentation and description project progresses, which can result in audio-visual recordings with incomplete or no transcriptions and translations, different versions of a given file, inconsistencies in representation as the researchers learn more about the language forms, meanings, and contexts over time, or change their mind about how words should be spelled or what things mean;

(5) Access to digital archive materials may require particular computer software, and training on its installation and how to use it for the purposes the user is interested in. For example, documenters frequently employ a software tool called ELANFootnote 6 to link their audio-visual recordings to their transcriptions and translations, and occasionally to the metadata and linguistic description. It is a powerful and complex tool that is difficult to use and requires individual instruction to learn, but without it the archival materials may be unusable;

(6) There may be some metadata about the deposit (information about the information within it); however, this is frequently limited or incomplete, especially in providing contextual background about why and how particular recordings, transcriptions, or translations were made, and how they relate to other material in the corpus (e.g. is a given song connected to a certain myth story? Are different stories about a character part of a larger story cycle or stages in a life history? Is a particular file the researcher’s reanalysis of another file, perhaps from a different researcher?). Metadata can also be inaccurate, especially if the project was done in a limited time, with people or places mis-identified, personal names misspelled or wrongly assigned, and so on. Sometimes these gaps and inconsistencies can be resolved by checking with the depositor (if they are still alive), or community members, or individuals who have relevant knowledge (such as an assistant who worked on a project, or a family member who knows the history of fieldwork or the people who participated).

For these reasons, it is important to discuss your needs and plans with the staff who run the archive, and seek their professional advice or training about the collection and the materials that make it up, as well as the ways it might be used for revitalization. In the USA, there is a national series of training workshops for this purpose called Breath of Life that involves University of California Berkeley and the Smithsonian Institution.Footnote 7 You may also need to interact and negotiate with the depositors or the people recorded in the particular materials you are interested in, or their descendants.

Documentation for Revitalization

We have seen above that the relationships between language documentation, language description, and language revitalization are complex, and need to be approached with care and attention, seeking advice and training where required. Sometimes language activists and communities can become disappointed when they find that a given document, recording, or digital corpus is difficult to use or not particularly useful for their needs. In this section, I provide some suggestions about how current and future language documentation could be made more valuable for revitalization purposes, without necessarily detracting from the other goals that the documenters may have. I suggest that:Footnote 8

(1) A wide range of members of the community, including those living outside the original location, should be encouraged to participate in the documentation, description, and revitalization planning and activities, rather than focusing on a limited number of older or ‘best’ speakers on the one hand, while considering outsiders to be ‘experts’ or ‘specialists’ on the other hand. Community members, activists, students, and enthusiasts can get involved in various ways which may lead to an increase in their language skills and practices, create stronger links with other speakers and elders in particular, and promote local language revitalization activities and changes in language attitudes. Such engagement can also lead to the creation and development of local community-based and community-driven language and culture archives, and often contributes to improving the quality of the resulting documentation (better translations, more culturally appropriate situations, a wider range of social activities recorded, etc.). Documentation and revitalization projects that include training, e.g. through grassroots workshops, can spread knowledge and skills more broadly, improve capacity building for community members, and increase their awareness of their own knowledge, skills, and agency;

(2) The range of speakers documented should include younger generations and those who may be less fluent in the heritage language. This will result in documentation of how non-traditional speakers use the full linguistic resources at their disposal, including the neighbouring or majority languages, which may involve borrowing or mixing. For some older speakers this kind of language use may be negatively evaluated, but for revitalization it is important to document how younger speakers and learners are actually speaking, and to determine what other sorts of language and expressions can be taught to them;

(3) The range of contexts documented should include non-traditional and contemporary interactional events, activities, and locations, such as community meetings, medical centres, places of employment, Internet and social media, and interactive games. This will generate examples of language use that learners, especially children, can engage with and put to actual use in their own daily lives;

(4) The kinds of interactions that are documented in the corpus should be expanded to include everyday, but often overlooked, aspects such as greetings, farewells, fillers, and discourse markers (like the equivalents of ‘umm’, ‘aah’, ‘mmm’, ‘well then’, ‘go on’, etc.), how to start, stop, continue, and change a conversation, as well as how to make an apology, tell a joke, express one’s disagreement, disappointment, or anger, and so on. These kinds of elements, which may be short and easy to remember, can be very useful for language learners, especially when they have more passive than active language ability (i.e. they can understand but have less ability to speak). An appropriately placed word or phrase like these can keep an interaction in the language going, or give a language teacher an indication that the learner is following, and thereby provide further opportunities for practice and learning;

(5) Researchers should document family language such as that between parents or grandparents and children as this can be useful for re-establishing transmission of the language between generations. This could include lullabies, songs, riddles, or other culturally appropriate language use, but also affective terms like the equivalents of ‘grandma’, ‘honey’, ‘sweetie’ etc., as well as terms of respect used to elders;

(6) Attention should be paid to short, fixed, or formulaic expressions that learners can productively use on a range of occasions. These might be things like the culturally appropriate equivalents of ‘excuse me’, ‘sorry’, ‘can I take that?’ or idioms, sayings and metaphors like ‘pass away’, ‘take the bull by the horns’, ‘don’t cry over spilt milk’ and so on. For more advanced learners, the formulaic or ritualized speech used within meetings or on ceremonial occasions can be very useful, both in terms of active proficiency in the language but also for acquiring culturally relevant knowledge (in Australia routines and short speeches like ‘welcome to country’ expressed in local Aboriginal languages at the beginning of a significant event are among those highly valued in language revitalization);

(7) The metadata associated with recordings could indicate that they might be particularly useful in certain ways for different kinds of language revitalization activities, such as ‘this is a good example of apologizing for intermediate level’. This could also include indications of potentials for adaptation in language learning, e.g. particularly clear recordings of individual words in a certain cultural domain that could be used for a quiz or puzzle;

(8) Contextual information that is notated for audio-visual recordings and provided with archival deposits should be as wide and detailed as possible, so that users now and in the future will be more easily able to make sense of how and why particular recordings were made, processed, analysed, and used. This kind of metadocumentation (documentation of the documentation), e.g. ‘this is a traditional story often told by grandmothers to children at bed time’, is extremely useful for language revitalizers (as well as subsequent researchers of all types). However it is frequently omitted as scholars and students concentrate their energies on recording, transcribing, and translating the examples of language features or use that they are particularly interested in, e.g. only the sentences containing a particular kind of grammatical structure. There is a balance to be struck between the work of documentation and metadocumentation, but more attention to the latter can have important and valuable consequences into the future for everyone.

If some or all of these ideas can be adopted and adapted in language documentation and description, then the people, contexts, and ways of speaking that are incorporated in the corpus can be made more relevant and useful for language revitalization.

Documentation of Revitalization

Individuals and communities engaged in language revitalization should be encouraged to document the processes, decision-making, events, successes, and failures of their work so that they and others can learn from them. Such documentation can also provide valuable resources for and feed back into ongoing curriculum design, materials development, testing, and evaluation. Language revitalizers can adopt the methods, practices, and tools of language documenters and make high-quality audio-visual records of learners’ knowledge and use of language and cultural phenomena, and accompany them with transcriptions, translations, notes, metadata, and metadocumentation, using the documenters’ software and data models where appropriate. In doing so revitalizers can contribute to the development and sustainability of efforts to increase the current and future domains of use and/or the numbers of speakers of the threatened languages they are concerned with. Some specific recommendationsFootnote 9 for activities that could be documented in this way include asking learners, either individually or in groups, to speak about their experiences in intergenerational activities, in families, in schools, or in other contexts. They could report what the older generation talked about, explain the situations, or describe what they saw or heard. By documenting these kinds of intergenerational activities as well as the ways that learners use the languages available to them after engaging in such activities, revitalizers should be able to identify psychological or interactional factors involved in successful or unsuccessful transmission of the language. This new understanding can then be used in further language planning and development, and can help to foster the vitality of the threatened languages.

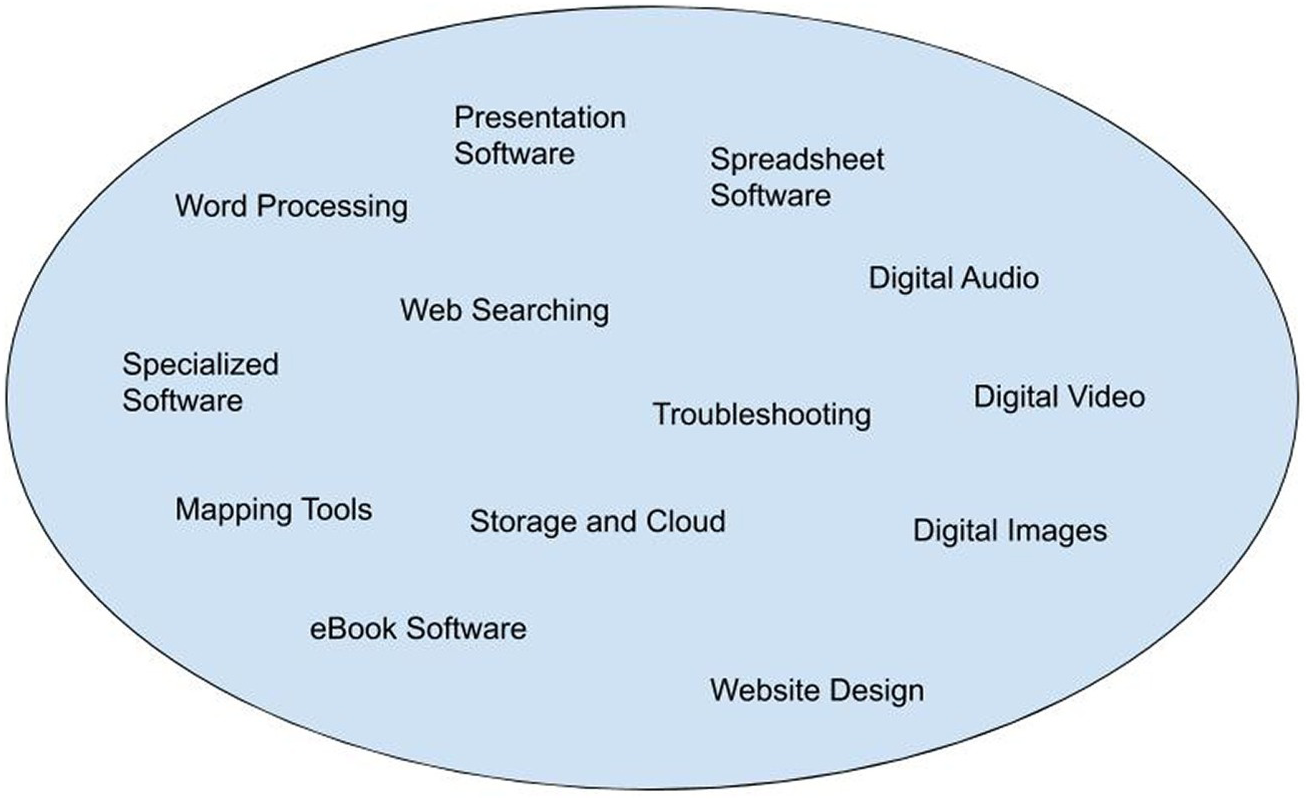

13.1 Technical Questions in Language Documentation

Most of our attestations of languages that are no longer transmitted intergenerationally or orally only exist in written form. The earliest audio recording that we can listen to nowadays is the so-called phonautogram of Au clair de la lune created on 9 April 1860 by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville. Since 1877, when Edison recorded Mary Had a Little Lamb, people have been able to record and play back sounds. The usefulness of recording equipment for documenting endangered languages was understood very quickly, and so the Passamaquoddy people living in Maine and Canada can now listen to the recordings of their language made in 1890 by Jesse Walter Fewkes. This documentation was done using technologies no longer used: wax cylinders.

Technological advances of the last few decades have transformed the language documentation processes. People are no longer likely to struggle with wax cylinders and less likely to have to deal with cassette tapes. A huge proportion of the human population has a cellphone. Most cellphones, and probably all smartphones, have some sort of an audio recording functionality. While most of them don’t yet compare to the professional quality that can be achieved using specialized digital recording devices with good quality microphones, they are more useful because they are readily at hand.

Before starting the documentation, it is a good idea to check the cellphone and especially its recording capabilities, the placement of the internal microphone (this should be considered the last resort – to be used only if there is no way of obtaining an external one), and possibilities of upgrading it. Simple and relatively cheap upgrade possibilities include buying an external microphone with a mini-jack or another appropriate connector (as more and more smartphones are moving towards USB Type-C and Lightning ports), or installing a dedicated recording application (as opposed to the one that comes preinstalled on the phone).

No matter whether one is recording on a phone or professional equipment, one quickly encounters the issue of file formats. In general, it is better to record in lossless formats (like .wav and .flac) as in this way more data is preserved and can serve for more purposes. The alternative (lossy) format is most often .mp3, which has two main advantages:

It consumes significantly less storage space: this might be important if there isn’t likely to be more space on the recording device and no possibility to copy the files anywhere else soon.

The second advantage of .mp3 is that one can be sure that everyone with a modern computer or cellphone is able to listen to it. The other popular format (.wav) is relatively old and can also be played back on many devices, but the files tend to become huge once the recording gets longer and might thus cause memory (RAM) problems when played.

The newer lossless format (.flac) creates smaller files, but many older devices lack the capability to play them back at all.

It is quite easy to convert a recording from a lossless format (especially .wav but also .flac) to a lossy format (.mp3) but not the other way around.

However, .mp3 also has disadvantages. One needs to keep in mind that converting .wav to .mp3 means losing sound quality and sometimes information. In the process of compressing the recording, some information gets lost and cannot be recovered. For some revitalization purposes .mp3 files are adequate because they are smaller and easier to share via the internet, but if we want high-quality, multipurpose recordings (e.g. to analyse the sounds of a language), high-definition formats are necessary. So it is recommended to record in .wav if you have the option, and convert to .mp3 if required.Footnote 10

In the end, the decision about the format is not as impactful as the quality of the recording. There are a few things that need to be kept in mind to ensure better quality. The first is to make sure that the device is actually in good condition (fully charged, with backup batteries or external powerbanks, and a well-functioning microphone). The choice of an appropriate microphone is also very important – depending on the context it might be a stereo or mono microphone of different configurations, eg. omnidirectional, cardioid, or hypercardioid. However it is good to remember the wise words of Chase Jarvis: ‘the best camera is the one that’s with you’ as here the same principle applies to microphones. If you cannot afford the perfect or even recommended microphone for the occasion, it is better to record with the device you have than to forgo recording altogether. The second is to try to eliminate background noises: maybe ask to close a window to a busy street or make sure the recorded person doesn’t have other commitments (like pre-arranged calls). If you can do it without causing discomfort to the person being recorded, consider bringing the microphone as close to them as is reasonable. The closer it will be, the better the recording quality.

Ideally the recording should be monitored through earbuds or headphones to make sure that you are actually recording what you think you are, and that the recording level is not too high nor too low. However, it is best to check first with the person being recorded if they are OK with this as it could create the impression of paying more attention to the technology than to themselves. You may want to do some practice recordings and let them listen back via earbuds or headphones to help understand the value of monitoring,

Similar concerns apply to video recording, but one also needs to think about image quality. This means choosing the best resolution (1080p is probably the best choice, with 4K being problematic to play back) as well as framing the subject, paying attention to lighting (avoiding over-exposure and underexposure), and making sure the video is stable for example by using a tripod (if possible) and by avoiding zooming.

Framing means creating compositions which are visually pleasing and appropriate to the subject (for example a wide angle for performances and rituals, and a closer one for personal interviews). It is always better to record video in landscape (horizontal), not portrait mode.

Avoiding over-exposure and underexposure is necessary because cameras try to balance the light and dark in what they are recording, so a poorly lit person on a bright background will be only a dark silhouette. If you have more time and space to set the stage for the recording, you can use a reflector, or a white sheet, out of shot to light a dark subject.

Making sure that the video is stable is easier in some cases and more difficult in others. When recording indoors one can often put the camera on a piece of furniture, which is a fast and simple option. However, it is not without disadvantages as things on furniture can fall off, or pick up noise from the furniture itself. It is not so easy outdoors and one might often want to use a tripod. These can sometimes be heavy, expensive, and unwieldy, however there are inexpensive lighter alternatives like GorillaPods, and many fold up to convenient sizes. A selfie stick can often double as a tripod (especially for a cellphone). If the video is recorded in motion (while walking, dancing, etc.), it might be a good idea to invest in a pocket gimbal, which can stabilize it.

When recording a movie resist the temptation to zoom in and out. Once you set the focus, leave it, and do not change it. In general, it is better to put the camera a good distance from the subject. This doesn’t mean that movies will only include wide shots: high resolution video can later be cropped digitally to create closer frames, so an edited finished product can include both wide framing and close ups.

Because of the need to place the camera away from the subject you might run into the problem of reduced audio recording quality – after all the microphone should be as close as possible to the people speaking, which stands in opposition to the need to place the camera away from the subject. Moreover, inbuilt camera microphones do not measure up to the standards of external microphones. Once again, it is a good idea to use an external microphone whenever it is possible. You can also record audio separately on a recorder or cellphone using a microphone near the people speaking. This can be combined with the video later to replace any poor audio from the camera itself.

Taking all the above points into consideration, it is often better to have someone else to help with recording. This isn’t so crucial in the case of audio, which often only requires starting the recording device and periodically checking if it still works. However, when a second person helps you with an audio recording, they can also monitor it using ear buds or headphones and thus ensure that not only it is working but also that the level is correct. Video requires devoting more attention to filming, so it is easy to become distracted from the topic of conversation, which might be offensive to the person who is being recorded and waste their time. Therefore, the help of another person or two with the camera, lighting, and recording might be very useful. Younger members of the community may be interested in getting involved in your project and can be trained to help with these things.

Documentary materials are in general very valuable, and safeguarding is important. This is done most effectively through multiple backups – copies of data created to protect it from accidental destruction. The golden rule is 3:2:1 ‒ always keeping three backups. Two of those backups should use different media or ways of storing (for example having 2 hard drives and a flash drive or a CD/DVD). Each way of storing data has its problems and thus your files should be properly stored and periodically checked, e.g. by recovering sample backup files and making sure they work properly. Hard drives (HDDs) can lose data if they are demagnetized. Disks (CDs and DVDs) require an optical drive and special software, and can fail over time. Even the newest solid-state drives (SSDs) can suddenly fail unaccountably. This is precisely why we recommend storing in at least 2 different ways and checking them periodically – to reduce the likelihood of all backups failing at once, and to restore any missing ones.

At least one backup should be kept separately from the others – in a different place (a different room, or even better, building) or in the cloud (on a dedicated Internet server). ‘Free’ cloud storage (that is available without having to pay for it) is available from many providers (like Google, Microsoft – OneDrive, Dropbox, mega, and many others) but using it always means that the data is uploaded to a corporation’s server, which might be an ethical problem for many people or a data privacy issue if the server is outside the user’s country, e.g. there are issues with the GDPR if cloud storage is in the USA. Still, these providers offer a lot of space without having to spend any money. However, no matter what kind of backup one chooses, it is important to do so. In general, it is recommended to do a backup at least every week, but when conducting fieldwork, it is best done whenever time permits – preferably every day.

You should also consider archiving important materials (audio, video, photos, text, computer files) to ensure long-term storage and availability. Archiving requires working with a trusted repository and involves selecting and editing the materials and describing them using metadata, e.g. who is in the recording, where it was made, what languages are being used. More information about archiving for endangered languages is available from www.delaman.org.

13.2 MILPA (Mexican Indigenous Language Promotion and Advocacy): A Community-Centered Linguistic Collaboration Supporting Indigenous Mexican Languages in California

In response to the social and linguistic challenges faced by Ventura County’s diasporic Indígena community (see Capsule 6.2), the Mixteco/Indígena Community Organizing Project (MICOP) has teamed up with linguists from the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) to create programs that foster language maintenance, multiliteracy, social justice, and Indígena pride. We refer to these activities collectively as the Mexican Indigenous Language Promotion and Advocacy project (MILPA).

MILPA brings together methods from sociocultural linguistics and documentary linguistics to carry out a range of community-based activities, some of which we outline in this capsule:

(i) Tu’un Savi (Mixtec) literacy classes;

(ii) Collaborative documentation of multiple Mixtec varieties;

(iii) College-level courses on language, culture, and society offered to Indígena youth;

(iv) A community language survey that explores language use and attitudes;

(v) The creation of Indigenous language materials for community use.

Community members gain technical training while collaboratively documenting their particular language varieties in UCSB’s year-long graduate field methods course, and from there they go on to lead MILPA programs while advancing their own language-related goals (see Capsule 11.1).

In 2015, MICOP extended an invitation to UCSB linguists to help provide training to community members interested in becoming Indigenous language literacy instructors. The team launched the program Tu’un Savi: Aprendo a Leer y Escribir en mi Lengua (‘I Learn to Read and Write in my Language’). Ten Indigenous students, UCSB graduate students, and university teachers participated in an online training course offered by María Gloria Santos Hernández of INEA (the Mexican National Institute for the Education of Adults). Out of the ten students, Gabriel Mendoza and Griselda Reyes Basurto were chosen to lead the first such pilot Indigenous language literacy course outside of Mexico, focusing on the Mixtec variety spoken by the greatest number of Ventura County’s Indígena population: San Martín Peras Mixtec. Course outcomes included basic vocabulary documentation and analysis of the sound system, or phonology (including tone), to enable the development of a writing system (orthography) (see Chapter 14), and revision of the course materials to match the San Martín Peras variety.

In 2017, the team continued to offer the beginning literacy course and began offering biweekly workshops to document and develop writing systems for other Mixtec varieties. The team works collectively on shared online spreadsheets to compile a multivariety Mixtec–Spanish–English dictionary, sheets for each variety that organize words by tonal melodies, a comparative verb database, and literacy primers.

MILPA offers a yearly course on language, culture, and society for MICOP’s Tequio Indígena youth activist group as part of UCSB’s School Kids Investigating Language in Life and Society program (SKILLS). This course is facilitated by UCSB graduate students and the Tequio Youth Coordinator, and high school and community college students earn college credit at California Lutheran University for their participation. Young people design and carry out ethnographic and linguistic research and community action projects that have resulted in the creation of a documentary film about Indígena youth identity, multilingual podcasts, poetry, online videos, and social media engagement written in Indigenous languages.

The first survey of Indigenous language use, language attitudes, and linguistic diversity among Ventura County’s Indígena population is being carried out by community leaders of the MILPA project with support from UCSB linguists. The survey explores community members’ and their families’ multilingual practices, linguistic challenges, and language attitudes, to better understand if and how Indigenous languages are being maintained, lost, or discriminated against in the community. In this way, we can get a clearer picture of language use and linguistic diversity among Ventura County’s Indígena population that can inform initiatives that foster language maintenance and justice.

The multivariety language documentation workshops, Tequio SKILLS courses, and UCSB field methods courses produce Indigenous language materials for expanding domains of language use and visibility in the community. Other examples of MILPA products include trilingual story books, coloring pages, card games, lotería (Bingo) games, vocabulary activities, and online language pedagogy activities that now have a Mixtec interface. Multimedia and multivariety materials foster language use and Indígena pride in the face of language shift and the challenges experienced by a diverse and marginalized community.

MILPA offers one model of community-based and multifaceted language maintenance and advocacy work. While designed to meet the various needs of this diverse and multilingual diasporic community, aspects of the project may be applicable for similar projects elsewhere.

13.3 Developing Innovative Models for Fieldwork and Linguistic Documentation: ENGHUM Experience in Hałcnów, Poland

Hałcnów, called Alzen in standard German and Alza in a local linguistic variety, was formerly a separate village. It now belongs to the city of Bielsko-Biała in southern Poland. Until the end of the World War II it was predominantly German; however, its inhabitants spoke Alznerish, a variety which is scarcely mutually intelligible with High German. Although most of the Halcnovians were not politically connected to Nazism, after the end of the war they suffered from severe persecution. The majority were either killed, banished to the Soviet Union, or resettled to Germany. The communist regime tried to erase all ‘signs of Germanness’ from public and private spaces. As a consequence, Alznerish also became invisible. When the political situation in Poland changed and post-war anti-German sentiment declined, most scholars supposed that it was too late to find any native speakers of the language. The fieldwork conducted in 2013 by the scholars from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań proved that they were wrong.

During the 2016 ENGHUM field school (see Capsule 12.2) in the nearby town of Wilamowice (where another endangered language is spoken – see Capsule 6.1), the major task of one of working groups was to document the linguistic and cultural heritage of Hałcnów. A multiethnic group consisting of seven people developed an innovative methodological approach to the problem. In the first phase of the fieldwork they focused on tracing the (hidden) elements of the linguistic landscape of Hałcnów. These actions were an attempt to discover material culture connected with Alznerish, but they also attempted to establish whether the German past of the village is now seen as an integral part of local heritage.

In the second part of the fieldwork the group was divided. While the first sub-group started to meet the native speakers and conducted unstructured conversations in Alznerish, German, and Polish, or some elicitation in Alznerish, the second group attempted to meet and talk to the most socially prominent people in Hałcnów: the priest, teachers, local historians, and activists. Except for the overt aim of this work – gaining knowledge on current ideologies and attitudes towards the language, asking about some other people who may know Alznerish, there was also another essential purpose for the fieldwork. In Poland researchers enjoy high respect in society. Moreover, as a result of the isolation of Poland in the communist period, foreigners from beyond the Iron Curtain are treated with esteem, especially outside big urban centres. Taking this into account, the interest of foreign scholars in Alznerish inevitably increased the prestige of the local linguistic variety. It was an indirect and non-intrusive way to change linguistic ideologies. The work of this group led to some unexpected discoveries. It appeared that local school students created a short glossary of the Polish variety used in Hałcnów, which is a testimony of emergence of a new linguistic community. What is of even greater importance, a previously unknown fluent speaker of Alznerish was identified. In addition, the fact that we were the first visitors ever to show interest in the villagers’ experiences meant that they felt able to share with us some previously unheard personal accounts of suffering in the post-war period.

In the third stage, the group acted together again. A meeting was organized of all Alznerish speakers. Strikingly, despite being neighbours, in some cases they did not know about one another’s skills in their mother tongue. Their joy from this discovery was noticeable. It has to be admitted that the scholars did not know Alznerish, but they could communicate in German or Polish. Very soon it turned out that using the latter language was more beneficial. When Halcnovians were asked questions in German, they replied in German, while the ‘distance’ between Polish and Alznerish was big enough to prevent constant code switching. The conversation concerned the pre-war time in the village and its ‘ethnography’. Currently, it is perhaps the only domain where Alznerish can be used. It was also interesting to find that the villagers could only use the past tense to talk about their experiences.

The last phase of research activities took place in Wilamowice. Halcnovians were asked to participate in an event summarizing the field school. They were treated as special guests and received an opportunity to speak publicly in their language. It was perhaps the first time after the end of the World War II, when Alznerish was not only used publicly without fear, but also attracted positive media attention.

The described pilot study is an innovative methodological proposal for short-term studies. It was focused on documentation of the language, networking of its users and either external or internal promotion of Alznerish. The combination of these three factors may give some hope that the effects of the study will be extended in time.

Introduction

Language communities and individual speakers of oral languages often express interest in the development of community orthographies, i.e. writing conventions for their ancestral languages. In this chapter, we review practical and ideological considerations in the writing of oral languages by asking some questions: ‘Who will write / read?’, ‘What will be written?’, ‘How will oral languages be reduced to writing?’ In our discussion, we focus on languages which have not been written before and where orthographies have been introduced only recently.

Purposes and Uses of Writing

Speakers of minority languages often accept discriminatory judgments from others about them and their languages, e.g. that their mother tongues are merely utterances without grammatical rules, which therefore cannot be written. The following example from the Khwe community in Namibia demonstrates the importance of writing in challenging these negative stereotypes. When community members wrote their language for the first time at a community workshop on the 15th of September 1996, Khwe became a written language. In a collaborative effort between Khwe speakers and linguists, an alphabet and other writing conventions were developed for their oral language. When writing his first Khwe words, David Soza Naudé, one of the workshop participants, who later became the key person in running community literacy workshops, stated with surprise and astonishment, ‘So we actually speak a real language’.

While reading and writing do not commonly play important roles in the daily life activities among the Khwe and other marginalized rural communities, establishing a community orthography might have an immense impact for them on a symbolic level. Although equating ‘real language’ with ‘written language’ reflects the widespread discriminatory judgments mentioned above, writing their language can boost their self-esteem and enhance their confidence and respect for their own language and culture (for more on attitudes and ideologies, see Chapter 8). For example, the Sandawe in Tanzania felt that their worth as a group increased after a Sandawe orthography was developed. Elisabeth Hunziker of SIL International recalls that for many years, ‘they had gotten used to being looked down upon by other ethnic groups of the country as being the ones whose language was impossible to pronounce, let alone write. Now with the alphabet, this was no longer the case’. Community members often desire written materials in their languages, which, once developed, are cherished and treasured. Books, booklets or even just small pamphlets are shared among community members and shown with pride to outsiders.

The practical use of community orthographies often begins with the production of sign boards with local place names that testify the ancestry of the land. These sign boards on the one hand may support community-based tourism, but on the other hand can also constitute arguments for claims for ancestral lands.

The publication of religious texts, such as hymns, prayers and the Bible, in as many languages as possible was for a long time at the core of Christian mission work in Africa, Latin America and Asia. With this aim in mind, missionaries wrote grammars and dictionaries of local languages. Many speakers of marginalized languages became literate by reading Christian texts, which still make up the bulk of publications in languages of many smaller-sized communities.

Another level in writing community languages is reached when they are used to take memos and to make notes at community meetings, to record decisions and detail agreements, etc. This is, for example, practised by the Juǀ’hoan community in Namibia. The advantage of using their own language in these official contexts is that the non-literate speakers, who often constitute the majority in many such communities, can also participate in and contribute to discussions concerning community affairs because the notes can be read back to them.

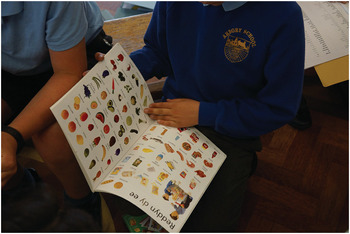

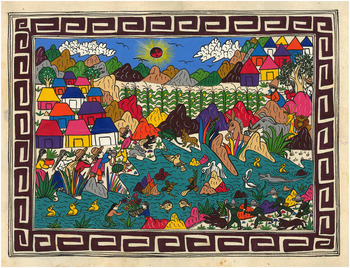

Writing oral languages can also serve as a means to document the community’s intellectual heritage, namely oral traditions relating to their history, rituals, environmental management, traditional economies, healing and spiritual well-being, etc. (see Figure 14.1). A critical take on reading and writing in hitherto oral languages emphasizes the importance of oral practices in many traditional societies. While oral traditions can be recorded in audio and video sessions and stored electronically, due to lack of basic infrastructure (access to electricity, Internet, etc.) in most rural areas, written documents are much easier to manage and access.

Figure 14.1 A Nahua boy reading an ancient creation story written in his variant. Chicontepec, Mexico.

Writing a language is essential for mother tongue-based multilingual education, and also for immersion education for language revitalization (see Chapter 15). This is particularly important, because literacy rates among speakers of threatened languages are often low and illiteracy is one of the crucial indicators to identify discrimination and marginalization. Children from such marginalized communities regularly perform poorly when their own languages are not used in the educational system.Footnote 1 Countless studies have demonstrated that children learn best in and through their mother tongues; despite this common knowledge, millions of children around the world are educated in languages other than their own. The plea for mother tongue-based multilingual education is an important argument for supporting the writing of oral languages. Government institutions, NGOs, as well as linguists may play supporting roles in communities’ attempts towards developing writing conventions, producing teaching and learning materials, fostering the use of the language and establishing language rights.

Finally, writing can play a crucial role in the survival of threatened languages. Where ancestral languages are no longer spoken in the family, children no longer acquire them naturally in their home environment. For this reason, ancestral languages are increasingly transmitted through formal and informal teaching. The design and production of teaching and learning materials for community languages are often considered central by language revival and revitalization movements. In these cases, the development and establishment of community orthographies are prerequisites, since these materials are mainly written, for example in booklets, readers, textbooks and dictionaries. When we work with last speakers of languages, learners don’t speak the languages fluently and often acquire new words through reading them. For this purpose, learning can be made easier if orthographies represent the speech sounds as closely as possible.

Designing Community Orthographies

Many linguists treat orthography development as a technical issue in which they identify the phoneme inventory and then aim at representing one distinctive speech sound with one character or symbol. Hangul, the alphabetic system used in writing Korean, represents the distinctive speech sounds of that language perfectly: words can be correctly pronounced simply by reading them, even by non-speakers. Most orthographies, however, especially those with long traditions, do not follow this principle. For example, the idiosyncratic nature of spelling is an obstacle in learning and writing English. Irregular spellings and pronunciation in English are the topic of many poems, including, for example, the classic English poem ‘The Chaos’, written by the Dutch traveller Gerard Nolst Trenité in 1920. It contains about 800 of the worst irregularities in English spelling and pronunciation, questioning for example why ‘done’ rhymes with ‘fun’ and not with ‘gone’. English is one of those languages in which the written forms of spoken words must be learned in addition to the oral pronunciation. Learning to speak English from written texts alone is therefore not possible. In Korean, on the other hand, it is possible to do so after having learnt the Korean alphabet, which in itself takes only a few hours.

Socio-political contexts and cultural traditions are often determining factors in the choice of specific orthography conventions, or even of different writing systems. Socio-political conditions affect all levels, namely the writing systems, orthographies or even the use of specific characters or symbols representing speech sounds.

Speakers of threatened languages commonly speak or even write other languages, which are more dominant than theirs. The orthographies and writing systems established for dominant languages are crucial in choosing writing conventions for a threatened language, especially when these dominant languages are used in literacy campaigns and formal education. There are often heated debates within communities between proponents of different orthographies, e.g. those who want to make it easier to switch to and from majority languages vs. those who want to use orthography to stress distinctiveness.

Religious affiliation has triggered the use of different orthographies for one and the same language, for example, when missionaries of different denominations introduced distinct writing conventions for Tumbuka in Malawi. Dialectal variation may also lead to different orthographies. For example, the Western Aranda people in central Australia want to distinguish themselves from the neighbouring Eastern Arrernte people through the spelling used in their language. For them, their own orthography is a key symbol of their distinct identity.

National governmental policies may demand the use of specific writing conventions, so cross-border languages may develop parallel writing systems in different countries. This led, for example, to different writing systems for Afar, a Cushitic language, in the three countries in which it is spoken: Afar is written in the Ethiopian script in Ethiopia, in the Roman alphabet in Eritrea, and in the Arabic script in Djibouti. Another example of state regulations on writing conventions is the enforcement of the use of Roman letters for the representation of click consonants by the government of Botswana. The orthography of Naro was developed according to this directive, whereas the orthographies of all related languages, including the well-established orthography of Khoekhoegowab, use the click symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet, which are easily acquired and used by community members, and which are used in all community orthographies of non-Bantu click languages in southern Africa (Figure 14.2).

Figure 14.2 Katrina Esau and Sheena Shah introduce the newly developed Nǀuu alphabet charts.

In the past, when starting to write an oral language, it was often the case that a ‘standard’ language was imposed, which ignored the regional, socioeconomic, gender and generational variation that is characteristic of spoken languages. Progress in information and documentation technologies makes it possible to represent different types of variation, and to produce materials, which reflect local ways of speaking as alternatives. Modern dictionaries and grammars are based on substantial collections of oral usage and might include ‘crowd sourcing’, i.e. the gathering of information from large numbers of people through the Internet. With this focus on spoken natural conversation, linguistic diversity and variation are recognized and respected. In such projects, speakers are instrumental in carrying out this research as well as in the processing and analysis of the language data.

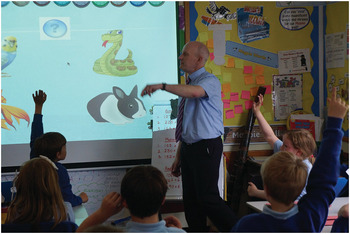

Ownership and Management of Orthographies

Community orthographies can stimulate intense emotional reactions among communities, for example, related to who controls and has the authority over language standardization efforts, or even more fundamentally, who owns a language. Communities have different options to coordinate and manage language activities. Community language boards may manage the development and establishment of writing conventions. This, however, is often not a straightforward exercise due to intra-community disagreements about writing conventions that can arise. Communities are not monolithic and there might be disagreements about whether and how to write languages. For example, different generations may have different opinions on the use of digital technologies; while younger generations may favour the use of social media, online video, text messaging, podcasts and various other technologies, older generations may be opposed to this (but see Figure 14.3). Interventions through government policies, conflicting conventions of different religious traditions, etc., often add to the complexities of the task of establishing writing systems for oral languages. It is imperative, however, that language communities themselves head and direct these efforts to ensure that their own interests are respected.

Figure 14.3 A postcard written by a young student of Manx.

Summary

There is no single best way to establish literacy in previously unwritten languages of predominantly oral communities. Even though one can learn from the various previous and ongoing attempts to write languages, community settings and conditions differ substantially. The level of literacy among community members (also in languages other than their own), whether a closely related language is already written, or if national policies prescribe writing systems or alphabets, are among the core factors that need to be considered when developing community orthographies for previously unwritten languages.

The possible purposes for and the uses of written forms for oral languages are numerous. In most cases, the development and production of written teaching and learning materials are essential when intergenerational language transmission is interrupted and when languages are thus learned mainly in formal or informal teaching settings. Where archived recordings of past or living speakers exist, such as in Australia or Hawai’i, community members can also relearn and regain oral competence in dormant ancestral languages.

Introducing writing for oral languages often has a positive impact on the self-esteem of their speakers and contributes to the improvement of their well-being. Visualizing their languages in writing can be an important tool in the empowerment of marginalized communities. Furthermore, many rural communities in various parts of the world have very little or no access to electronic language resources (e.g. no electricity, no recording devices, no smartphones, etc.), making the use of audio or video clips in teaching efforts problematic. For that reason, in the foreseeable future, writing an oral language may still prove to be essential for the production of teaching materials, and literacy will remain the main tool for accessing knowledge and information (Figure 14.4).

Figure 14.4 An exercise book for (writing) the Lemko language (Робочий зошыт до лемківского языка), Barbara Duć/Варвара Дуць.

Most important for the development and establishment of writing for oral languages – besides communities being in control of all activities that aim at establishing community orthographies for their languages – is that community members wish to have their languages written.

14.1 Orthographies and Ideologies

Very often, language communities and activists want to make their language visible through developing a script, writing system, orthography, individual letters or type fonts. The choices involved in deciding the graphic layout make language ideologies tangible. Developing a written form (graphization) of a language (variety) not only involves the selection of an appropriate orthography, but also making decisions concerning cultural, religious, political and historical matters.

Ideological factors are therefore fundamental when considering how to write minority languages. However, it is always the community who should have the decisive voice when adopting script, writing system and orthography. Of course, there are often disagreements within a community on writing and/or orthography.

Many minorities use writing to symbolically mark their territory, using public signs to mark the names of settlements, municipalities or other places within the area of a dominant language. Sometimes the languages used in the signs are perceived as rival or competing against each other – occasionally this also applies to rival orthographies for the same ‘language’ (e.g. Provençal/Occitan orthographies in southern France, or ‘standard’ vs. ‘dialectal’ forms, e.g. in Italian Lombardy, Piedmont or Veneto). Place names may be written in two or more languages or writing systems, and it is quite common for a name in one language to be removed, altered or painted over as a visible sign of ethno-linguistic conflict, an example being a letter V in an Anglicized place-name in Wales replaced by an F.

Explanation of Terms

A script is a set of graphic signs (graphemes) for writing languages, which contains information about the basic level of language to which its signs correspond: words, syllables or phonemes.

A writing system is the implementation of a script (or sometimes elements of more than one script) to form a complete system for writing a particular language variety; a writing system can be standardized by means of an orthography, i.e. norms for spelling, diacritics (e.g. accents etc.) and punctuation, which are often arranged and published as spelling rules and orthographic dictionaries. These norms may be explicit or implicit: implicit norms often allow a greater degree of variation than explicit orthographic norms.

Fonts or typefaces are graphical variants, which can be distinguished within a script.

Traditionally, a script or graphic layout has been ideologically related to culture, and even more often with religion. Many people spontaneously associate the Cyrillic script with the Christian Eastern Orthodoxy, Arabic with Islamic tradition, Hebrew with Judaism, Devanagari with Hinduism and Chinese characters with the East Asian cultural sphere. For a long time, the Latin script was linked to the Western European tradition and Western Christianity. In regions of Europe where Protestant and Catholic traditions rivaled each other, the visible factor used to differentiate them was a type font: protestant writings adopted Blackletter or Gothic script, while Catholic publications used Antiqua typeface.

Throughout history, scripts have been designed specifically for individual languages – examples being the Georgian scripts (ქართული დამწერლობა): Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, and Mkhedruli, the Armenian Հայերենի այբուբեն / Hayereni aybuben for Armenian, the Korean 한글 / Hangul, or the syllabaries ひらがな/ Hiragana and カタカナ/ Katakana for Japanese. These and other ‘national’ scripts became carriers and symbols of various ‘nation-state’ ideologies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The same nation-state ideologies were also behind the adoption or imposition of dominant scripts as writing systems for minority languages (no matter whether they were linguistically related or not), e.g. in Georgia for Abkhazian, Ossetian, Svan, Megrelian, or in Japan for Ainu or Ryūkyūan.

The Hebrew alphabet (אָלֶף־בֵּית עִבְרִי / Alefbet ‘Ivri ) has served as a marker of Jewishness, and as such has been applied to most of the Jewish languages spoken all over the world (Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Persian, and many others). The same alphabet was originally adopted by the Karaims, a Turkic people of Judaic religious tradition. In the nineteenth/twentieth centuries, the Karaim communities in Lithuania and Poland decided to switch from Hebrew to Latin script in order to visually mark their separation from Jewish ethnicity. Later, Karaims under Soviet rule had to adopt a Russian Cyrillic-based orthography. Even some Yiddish speakers in the same period thought about switching from the Hebrew script to the Polish Latin-based writing system. From a contemporary educational perspective, it might be easier to learn using the same script as the dominant education system, although it can also encourage faster language shift. The majority of world’s languages have not been recorded in writing and there are fewer scripts and writing systems than language varieties in the world. Furthermore, many language communities have made changes to their orthographies or individual graphemes (e.g. Vietnamese and Turkish switching to Latin script).

Any language or language variety can be written with any writing system or script, although e.g. arguably syllabaries are more suitable for languages with Consonant+Vowel syllables. However, there are many factors involved in devising or adapting a writing system or orthography, and these must be considered in order for an orthography to be effective. The process is more complex than is commonly realized.

Here are some key factors to be taken into consideration when designing effective orthographies:

(1) Governmental, administrative and legal policies, obligations and restrictions, which must be considered when working on community-driven (bottom-up or grassroots) projects. For example, in Ghana all writing systems have to use the national orthographical conventions.Footnote 2

(2) Cultural or religious traditions, e.g. ease of access to earlier written materials such as pre-Conquest Central American manuscripts, visual appearance (i.e. symbolic meaning of individual graphemes), the values attached to a script or typeface (e.g. the close relationship between Arabic script and Islam).

(3) Linguistic factors, including sound-grapheme or meaning-grapheme correspondence (according to the script type), or how to decide where word breaks come.

(4) Educational and social factors, including literacy issues and ease of learning, access to the learning of additional language.

(5) Sociolinguistic aspects – including language ideologies, attitudes, how to choose the ‘standard’ variety and its applicability to other varieties of the language in question.

(6) Need and importance of written language documentation for the community.

Inventing a script is one way that a community can try to create a distinct identity. Sometimes creating and developing a uniquely new script is the most accepted way to develop and promote social literacy within a language community. One such case is the well-documented Indigenous script of N’ko in West Africa. The N’ko ‘social orthography’ has successfully competed against other older writing systems that have been better propagated in the colonial and national literacy education programs. N’ko’s popularity results from the script’s strong linguistic and cultural relevance to the Mande communities and their Indigenous knowledge.

Some minority language communities prefer to use a special font (such as the contemporary Basque Harri / Vasca or the historical Gaelic script for the Celtic languages), or a unique, recognizable type style (e.g. mixed-case oblique Irish vs. capital lettered English on road signs in the Republic of Ireland). In such cases, the graphic features of the script became symbolically relevant, acting as distinctive markers of the linguistic landscape. On the other hand, some members of the community might object to such ‘ethnic fonts’ as markers of folklorization or archaization.

If a language community uses the same script as the surrounding dominant language(s), individual graphemes (e.g. particular letters in alphabets) or even individual diacritic signs, i.e. additional graphic marks of letters, might become ideological carriers and visible indices of identity. Examples of the latter include, e.g.