Who This Book Is For

Local languages have been falling into disuse and becoming forgotten in an increasingly accelerating pace over the last century or so: media and scientific reports keep reminding us, with quite alarming statistics. However, the last few decades have also witnessed another steadily growing trend: initiatives, both grassroots and top-down, to counteract the devastating loss of linguistic diversity and to promote multilingualism and the use of local languages. There have been programs and activities that can be considered real success stories or at least important steps toward them, even if revitalizing and supporting endangered languages is a never-ending task. But it is a task that can be planned, implemented, evaluated, and brought into a next stage thanks to this growing body of individual and collective experience and generated knowledge.

This book is meant for anyone who feels concern or even pain because of the loss they and their communities might face; it is for people who experience joy when speaking their languages and want to have them heard, spoken, and strong. It is for people who learned their languages, or who wish to learn them, from their parents, grandparents, community members, or on their own. It is also for people who want to pass their ways of speaking to children and peers. As an Indigenous teacher in the Navajo reservations recently shared with one of us, the most committed parents wanting their children to learn the ancestral Diné language were those who grew up in borderland towns and lost it themselves. Loss can be an empowering stimulus to act. It can also lead to a profound joy of reclaiming a language, learning, speaking, and passing the language to other people, to experiencing the world through its unique perspective, to accessing the knowledge generated and transmitted by the ancestors. But language revitalization is not about going back to the past; it is about acting in the present and heading toward the future, recognizing that the past provides an important foundation and stimulus to achieve it.

This book emerges from the results of the collaborative Engaged Humanities projectFootnote 1 and reflects the philosophy of this collaborative initiative. It has been created jointly by community members and language activists, as well as by educators, students, and academics interested in developing fair and nonpatronizing ways of working with local communities and in response to communities’ initiatives and needs. All the contributors generously share their perspectives, thoughts, and practical experience, in the hope of inspiring others. Our project has shown the potential and utility of learning from other contexts, even geographically or culturally remote ones. We also learned that mutual empowerment is possible. The profound respect we have developed for different knowledge systems and approaches can not only decolonize our research and practices, but also help to develop more effective language revitalization strategies.

What This Book Does

The aim of this guidebook is to provide practical help and guidance on how to approach and plan language revitalization. We want to stress from the outset that there is no ‘one-size-fits-all,’ lock-step solution to language endangerment. Just as each language is different, the contexts in which each language is used are different, and the reasons why its use is declining might also be different. While the case studies are intended to help readers learn from each other, perceived similarities between communities can lead to underestimating or ignoring differences that may seriously influence revitalization efforts, as it is risky to assume that a specific approach implemented in one case will bring similar impact and results in another community. It is important to understand each context in order to address its unique features, even if the experience of others can be very useful; this book will provide insights into how to go about this in a principled manner.

Our intention is also to fill the dearth in available literature on the topic. Most of the relevant existing works are specialized, academic publications that reflect more the views of researchers than the perspectives, goals, and interests of communities and their members interested in revitalizing their own languages. We want this book to be affordable and accessible to local people. The guidebook provides members of language communities and other readers with concrete ideas and real examples of actual experiences and strategies, as well as essential background knowledge that they will need in order to launch successful grass-root initiatives.

What This Book Is Like

For this reason, our aim for this book has been to create readable content presenting a broad range of options and voices. We are convinced that accessible and understandable style, free of academic jargon, does not result in simplification, nor does it make the publication unfit for students or researchers. The organization of the book is intended to help readers conceptualize and plan practically oriented projects. The chapters are written by contributors with a wealth of practical and research experience in language revitalization that is being carried out in many countries around the world. Each chapter includes ‘Capsules’ that share insights from the direct experience of contributors.

The final result covers language revitalization seen as a holistic, multilevel, multiphase, and long-term process, as completely as possible without resorting to a 500-page monograph or a 1,000-page encyclopedia.

It is primarily practitioner-oriented. The fact that our book is designed first and foremost as a practical guide implies that it is as ‘hands-on’ as possible (e.g. the capsules relate to the real-life experiences of various revitalizers), backed up by reliable research (the chapters are for the most part written or cowritten by recognized scholars who engage in revitalization activities). Therefore, the book is intended to present only as much theory as needed to support the practical guidance, as well as many relevant, hands-on examples. We avoid the one-size-fits-all approach by not presenting any single possibility as the best or the only one. The guidebook shares good practices, different approaches previously applied in specific cases, and new possibilities currently being explored or put into practice. We discuss, for example, planning aims and objectives, understanding and addressing language attitudes, the advantages and disadvantages of writing or standardizing your language, policies and fundraising, and suggestions for practical activities including music, arts, and teaching and learning endangered languages. We also want to draw our readers’ attention to the economic value of local languages and possible marketing strategies for language revitalization.

Where We’re Coming From

What are our ideological background and motivations? In the first place we wish to stress we aren’t imposing a particular party line – the point of presenting options is to provide tools and share knowledge to facilitate making informed decisions and undertaking specific steps toward language revitalization. We also think that it is important not to ‘exoticize’ Indigenous viewpoints – many endangered language community members live in cities and/or have been acculturated to majority lifestyles.

In nearly every part of the world, smaller or less powerful languages are being used less and less, while the use of larger, more dominant languages is growing. Some people do not see this as a problem; indeed, some even welcome it, saying that it is more useful for children to learn regional, national, or international languages of wider communication. We believe it is important for language revitalizers to understand their own motivations, and to develop arguments to counter critics and gather support. The authors and editors of this book see language endangerment and loss as linked to the marginalization of Indigenous and minoritized peoples and their cultures. For us language revitalization is therefore a key component of empowerment, reclaiming identities, and challenging colonialist attitudes.

In fact, the majority of people in the world speak more than one language, using different languages and styles of speaking for different purposes in their daily lives. Multilingualism is beneficial, both for personal intellectual development and for social integration. We need to get across the message that engaging with wider societies and learning major languages does not mean that people need to abandon their own linguistic identities and cultural heritage.

A Note on Terminology

Many concepts, terms, and approaches have been developed in the area of language revitalization, including language maintenance, language revival, or language reclamation. We should keep in mind, however, that these are ideas created and promoted by researchers and often not the conceptualizations of communities themselves. These concepts are also strongly influenced by biological metaphors of Western science and not necessarily seen that way by language communities. Therefore while referring to the broad and open meaning of ‘language revitalization’ this book avoids making strict conceptual distinctions and definitions, leaving decisions on how the process should be defined to the people involved.

The Need for Reflection

There are many different ways of reacting to language endangerment. As mentioned, some people see it as a sign of progress. Some are in denial, especially if they feel partly responsible for not passing their languages to their children. Others feel nostalgic for a view of the past that, for them, is linked to their heritage language. But there are some who feel motivated to do something. Quite often, they feel a sense of urgency, because they can literally see their language dying – in Guernsey or Wilamowice, for example, most speakers are now very old and we’re losing some every month or two. So it is not uncommon for language activists to rush into the first activities that come to mind; however, this might not be the best use of their time or energy.

This is why we want to encourage critical discussions about other ideas and real situations. For example, people often assume that because children seem to learn languages easily, and because schools are effective at killing minority languages, they need to get their languages taught in schools. But if our languages are not part of the mainstream curriculum, and have no materials or trained teachers, they often end up being taught for half an hour a week, after school or at weekends, by people who are passionate about their language but don’t know how to teach it. Very few children will become fluent from this kind of teaching, and some will be put off the language for good; they may also absorb the implicit message that the minority language is not good enough for ‘proper’ school. And the language activists have no time for other activities that might be more effective, such as conversing with other adults to maintain or increase their fluency. It is important to take time to find out more about the language situation and to reflect on potential courses of action and their outcomes, in light of the resources available – human, financial, and in terms of language teaching and reference materials. This book discusses aims and objectives: short-term, medium-term, and long-term. We believe that spending a bit of time to undertake a survey of language attitudes, and who speaks the language, and how well, will repay the time and effort by providing a sound basis for planning other activities.

This book aims to share the richness of multiple perspectives and examples as well as a coherent, logical sequence of complementary topics to consider while planning language revitalization or struggling in the midst of this process. It is intended not only to provide revitalizers with coherent knowledge and a strong point of departure, but also to encourage, inspire, and empower them. And, as we have already said but wish to emphasize again, we avoid a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach by presenting concrete examples and providing readers with the tools they need to make their own decisions.

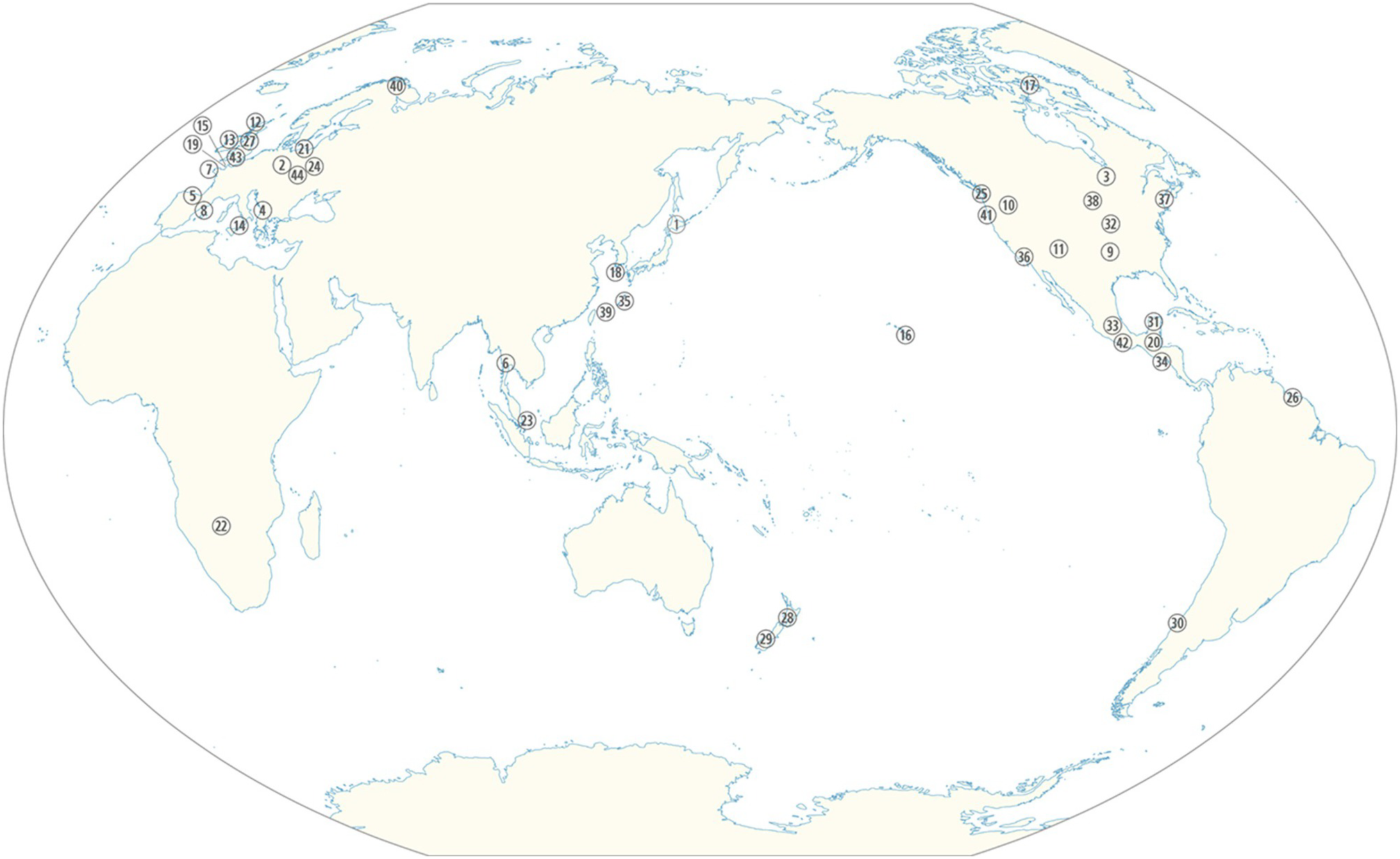

Examples of language revitalization in this book (see map on page 6)

1. Ainu

2. Alznerish

3. Anishinaabemowin

4. Arbanasi

5. Euskara | Basque

6. Black Tai | Lao Song

7. Breton

8. Catalan

9. Cherokee

10. Chinuk Wawa

11. Diné | Navajo

12. Scottish Gaelic

13. Irish Gaelic | Irish

14. Greko

15. Guernesiais

16. Hawaiian

17. Inuktituk

18. Jejudommal | Jejuan, Jejueo or Jejubangeon

19. Jèrriais

20. Kaqchikel

21. Kashubian

22. Khwe

23. Kristang

24. Lemko

25. Lushootseed

26. Makushi

27. Manx | Manx Gaelic

28. Northern Māori

29. Southern Māori known as Kai Tahu

30. Mapudungun

31. Yucatec Maya, maaya t’aan

32. myaamia | Miami-Illinois

33. Nahuatl

34. Nawat | Pipil

35. Okinawan

36. Pahka’anil

37. Passamaquoddy | Maliseet | Wolastoqi

38. Potawatomi

39. Ryūkyūan

40. Sámi

41. Tolowa Dee-ni’

42. San Martín Peras Mixtec | Tu’un Savi (Mixtec)

43. Welsh

44. Wymysiöeryś | Vilamovian

Map of examples of language revitalization in this book