Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- map

- Part I For the increase of the divine service

- Part II All Saints’, Bristol, and its parishioners

- Part III Commemorating the dead

- 6 ‘In possession for the profit of the church’: Securing commemoration in the parish

- 7 ‘For all future time’: The Halleways’ Chantry

- Coda

- Part IV Leaders and administrators

- Part V Ordering the parish

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

7 - ‘For all future time’: The Halleways’ Chantry

from Part III - Commemorating the dead

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- map

- Part I For the increase of the divine service

- Part II All Saints’, Bristol, and its parishioners

- Part III Commemorating the dead

- 6 ‘In possession for the profit of the church’: Securing commemoration in the parish

- 7 ‘For all future time’: The Halleways’ Chantry

- Coda

- Part IV Leaders and administrators

- Part V Ordering the parish

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Summary

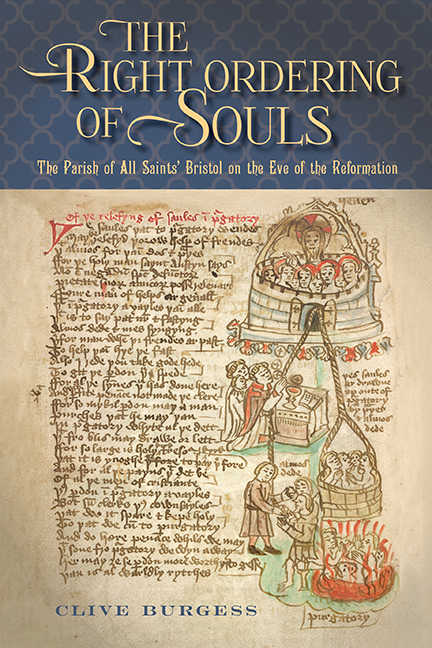

A perpetual chantry represented an ambitious form of devise clearly benefiting the parish, with property set aside yielding rent sufficient both to pay a celebrant's stipend and maintain the endowment, sustaining the income in perpetuity and, ideally, providing a little extra for the host institution. Such chantries were never numerous: few individuals had the requisite property; fewer still held this without prior obligations to family or heirs. Even though perpetual chantries functioned as parish enterprises, ordinarily we now have only snippets of information generated and preserved by government and reflective of their inception and demise. Foundation frequently produced a licence to alienate in mortmain entered on the Patent Rolls; the dissolution, in the first year of Edward VI's reign, produced the Chantry Certificates, recording a few details for each institution, whose endowments the government proceeded to absorb. But the All Saints’ archive discloses just how much documentation a parish could compile when managing such an arrangement: Thomas and Joan Halleway's chantry, inaugurated in All Saints’ in the 1440s, generated copious materials. In addition to a variety of foundation documents, we have in particular a good series of accounts, from 1463–64 and continuing with only a few gaps until 1540, and these provide a plethora of detail concerning the day-to-day management of the chantry and its endowment. Although surely once compiled for all perpetual chantries, such accounts survive only rarely, but – it must be emphasised – seem usually to have been kept separately from the churchwardens’ parish accounts. The Halleways’ chantry accounts reveal how much care a parish might lavish on such a foundation, for it was clearly of the utmost importance to All Saints’ that it should flourish.

To keep a chaplain continually: the foundation of the Halleways’ chantry

While no will survives for Joan Halleway, Thomas has a will of sorts preserved, not in a properly recognised record of probate but in the All Saints’ deeds collection. It was made on 10 October 1449, which, given that the All Saints’ benefaction list reveals that Thomas died on 13 December 1454, may initially seem strange. A long interval between giving a will and its probate needs no comment, however. Bristol's mercantile community habitually made ‘fail-safe’ wills well in advance of death.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- 'The Right Ordering of Souls'The Parish of All Saints’ Bristol on the Eve of the Reformation, pp. 223 - 251Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018