Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- map

- Part I For the increase of the divine service

- Part II All Saints’, Bristol, and its parishioners

- Part III Commemorating the dead

- 6 ‘In possession for the profit of the church’: Securing commemoration in the parish

- 7 ‘For all future time’: The Halleways’ Chantry

- Coda

- Part IV Leaders and administrators

- Part V Ordering the parish

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

6 - ‘In possession for the profit of the church’: Securing commemoration in the parish

from Part III - Commemorating the dead

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 May 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Miscellaneous Frontmatter

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- map

- Part I For the increase of the divine service

- Part II All Saints’, Bristol, and its parishioners

- Part III Commemorating the dead

- 6 ‘In possession for the profit of the church’: Securing commemoration in the parish

- 7 ‘For all future time’: The Halleways’ Chantry

- Coda

- Part IV Leaders and administrators

- Part V Ordering the parish

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Summary

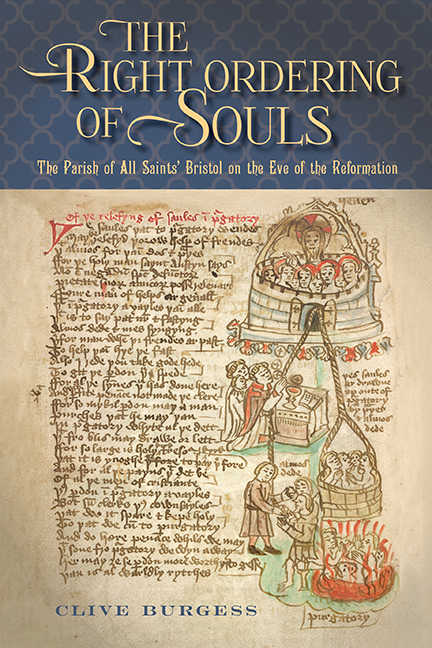

Synodal legislation from the thirteenth century had imposed on the laity – in practice, on parishioners – the obligation both of maintaining the fabric of the nave and tower and of ensuring that the incumbent possessed sufficient equipment for the seemly celebration of the parish liturgy. As a result, gifts of money or goods intended either to maintain the church fabric or to equip the parish would alleviate the burdens that present and future generations of parishioners ordinarily had to bear. Similarly, property devise, providing rents either to underwrite stipendiaries or to increase parish income, profited present and future generations who benefited from more lavish services without the obligation to pay for them. The All Saints’ archive suggests that whereas the donation of money or goods remained relatively steady in the century or more before the Reformation, the devise of property quickened, with significant results. Each practice will be investigated in turn.

‘Longing to be prayed for’: Communal commemoration within the parish

The bequests of money and goods made by parishioners loom large in the All Saints’ archive, and entries in the All Saints’ Church Book benefaction list occasionally mention something of donors’ motivation. Among those who gave sums of money, William Palmer, a goldsmith of London, who gave 40s., Robert Derkyn a London mercer, who gave 20s., and Martin Symondson, a hardwareman ‘of this parish’, who also gave 20s., all specifically did so ‘to be prayed for’. Thomas Abyndon, parishioner and inn-holder, ‘at his decease gave unto this church in money 40s.’, and did so ‘as a good doer’. Others gave items, usually with a liturgical purpose in mind. Richard Ake ‘gave to the use of the vicar for the time being one antiphonal, price £10, in order to be prayed for among the benefactors of the church. God have mercy on his soul.’ Other donations exhorted prayer, sometimes blatantly. Alice Chestre, as we have seen, gave ‘a hearse cloth of black worsted with letters of gold of H & C & A & C and a scripture in gold, Orate pro animabus Henrici Chestre et Alicie uxoris eius’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- 'The Right Ordering of Souls'The Parish of All Saints’ Bristol on the Eve of the Reformation, pp. 193 - 222Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018