To the extent that an historian can justifiably use the slippery concept of personal identity, it is usually conceded that an amalgam of various social roles and recursive human behaviors is involved. The problems then quickly multiply.Footnote 1 How many of these roles or behaviors were available to an individual in any specific circumstance? And how were the given or selected roles mobilized and in what contexts? To begin to answer these questions, we must attempt to determine the range of inherited and arbitrary items assigned to a person as opposed to the number of more voluntarily adopted and assumed cultural roles and resources – elements out of which an individual formed his or her own identity and had it shaped by others. Even where the choice of one element was possible – for example, an adult who embraced the new faith of Christianity – one is still faced with decoding the circumstances governing the salience of this identity over any others. In what circumstances might the new Christian choose or not choose to forefront his or her new religious affiliation? We are then compelled to explain why the particular salience exists in that circumstance.Footnote 2 In many cases, especially in complex ones that traverse significant lengths of time, an individual was not always essentially person ‘x’ or person ‘y’ but rather, to use one possible example, an adult, a man, a father, a Roman (citizen or not), a Gaul, a Trevir, a soldier, a Christian, a veteran, a farmer, a municipal magistrate, or, more likely, some combination of these by turn. What is being considered here is not some high-flown Barthian theory about ethnic boundaries. What is being envisaged, rather, is a series of more tangible aspects of social existence that allow persons to define themselves and others to identify them.Footnote 3 Among these items, a recent historical analysis relevant to our time has listed the following ones: language, arms and modes of fighting, costume, bodily styles (e.g. hair arrangements), cuisine, and similar cultural attributes.Footnote 4 One can easily think of other less material items such as traditional occupation and religious adherence. Given precise contextual factors, only some of these are properly construed as ethnic in nature. Even of this limited number, most usually converge in a configuration that identify one as a specific kind of person, like a centurion in the Roman army as opposed to one who has a linguistic-kinship-locational ethnic identity, like Numidian or Gaetulian. But the two could easily reinforce each other, as when a Musulamian man served in the First Flavian Cohort of the Musulamii. Such restrictive conventions are complicated by the liberal use of metaphor. Christians, for example, conceived of themselves as a ‘new race’ or ethnos.Footnote 5 For many persons in the Roman Empire beginning in the later first and early second centuries, but not before, a new potential identity had been created. Further to complicate the metaphor, men and women who were or became Christians began deploying familial models of power and a broad kinship terminology to express their relationship to an all-powerful god who was a father to his children. Christians as Christians became persons who were one another’s brothers and sisters. So even salience has problems with it. A restricted emphasis for a person – ‘I am (in essence) a Musulamus’ – can work if he can front or parade certain aspects of personhood while telling other ones to get lost or at least to hide in the closet for a while. Some given aspects of our personhood, however, are so durable that doing this is difficult. They might not accept the repudiation.

As has been perceptively noted, ‘in a multinational empire whose makeup was multiple, heterogeneous, unequal, and sometimes hostile and badly integrated, the identity of each individual was inherently complex’.Footnote 6 In making these remarks, Veyne suggests that the forming of personal identity, including civic or ethnic identities, was complicated by the very existence of the Roman Empire. An exemplary case has been provided for Africa by the interrogation of a witness before Zenophilus, the Roman governor of Numidia, in the year 320. Court appearances, after all, were one of the contexts that hailed forth assertions of who one was. Asked to identify himself, the man declared: ‘I am a teacher of Roman literature, a Latin grammarian; my father is a decurion here in the city of Constantina, my grandfather was a soldier who served in the imperial comitatus, and our family is descended from Maurian blood.’Footnote 7 So: occupational profession, inherited civic status, inherited military status, and ethnic lineage; each of them was an element configured by Roman imperial power. The variations and permutations necessarily proliferate. I would therefore like to focus on a single case of ethnicity that illustrates some of the problems. The man’s life is significant because his ethnicity was strongly implicated in the various identities that were created and offered to individuals by the Roman imperial state. His career has already received some attention but, I believe, it still poses a series of interpretive problems that make him deserving of more. His life is a manifest instance where the Roman imperial state, a complex and powerful institution, helped, by the use and application of its cultural and administrative categories, to create new possible identities. Let us first consider the bilingual Latin/palaeo-Tamazight inscription on our man’s gravestone found at the town of Thullium (modern Kef beni Feredj), directly north of Madauros in the proconsular province of Africa (see Fig. 4.1).Footnote 8

Figure 4.1 Tombstone of Gaius Julius Gaetulus / Keti son of Maswalat.

Latin Text

C(aius) Iulius Gae[tu]|lus vet(eranus) donis | donatis torqui/bus et armillis | dimissus et in civit(ate) | sua Thullio flam(en) | perp(etuus), vix(it) an(nis) LXXX / h(ic) s(itus) e(st)Footnote 9

Gaius Julius Gaetulus, veteran soldier, having been awarded the honors/military decorations of torques (neck bands) and armillae (arm bands), and having received an honorable discharge from the army, held the post of Perpetual Flamen in his own hometown of Thullium. He lived 80 years. He is buried here.

Palaeo-Tamazight Text

Keti, son of Maswalat, the servant/soldier of the supreme chief/king, from (the tribe of) the Misiciri, from (the subtribe of) the Saremmi, / high priest [?] KT’i W MSWLT | MSWi MNKDi | MSKRi S’RMMi | MZBiFootnote 10

The Latin text on the gravestone set up for our man tells us that the deceased named in in the epitaph, Gaius Julius Gaetulus, was a decorated veteran of the Roman army who returned to his home town where he held the high-ranking priesthood of flamen perpetuus in its municipal hierarchy. Gaetulus’ military decorations reveal that he received some of the imperial army’s most prestigious awards. The dona militaria of armbands and neck torcs were awarded only to Roman citizens.Footnote 11 Almost certainly a citizen from birth, as indicated by his tria nomina, our man probably served in one of the legions of the imperial army, perhaps (but not necessarily) the Legio III Augusta in Africa itself.Footnote 12 In the other text on the same stone, which is inscribed in the palaeo-Tamazight script, this same man is called KT’i son of MSWLT, Keti son of Maswalat, an ‘imperial servant’ or ‘soldier of the emperor’ from the people of the Misiciri, from the sub-people of the S’RMMi.Footnote 13 His personal name and his larger community identity in the African language are completely different from his public face in the Latin text on the same stone. About when did Keti die and to when does his gravestone date? Some think as early as the late first century. Given the rate at which novel elements in the formal language and abbreviated elements in funerary epitaphs developed and then penetrated the more remote highland zones, however, it seems more likely that we are considering a date in the early to mid second century.Footnote 14

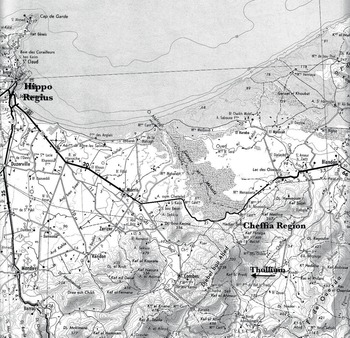

Manifestly Gaetulus’ identity involved a number of locational factors that can be specified. First among them was his home town of Thullium. Then followed the larger region of the Cheffia, the highland lying to the southeast of Hippo Regius in which Thullium was located (see map Fig. 4.2). Further encapsulating both the Cheffia and Hippo was a larger region lying west of the frontiers of the old republican province of Africa which, for convenience, we might call either eastern Numidia or western Proconsularis.Footnote 15 Parts of the latter large region were far western extensions of the Khoumirie (Kroumirie) highlands, while other parts of it stretched further southward and westward, ringing the southern horizon of the Hippo plain.Footnote 16 The highlands are sometimes referred to as ‘the mountains of the Medjerda’. They are one of the few micro-zones in the Maghrib east of the Atlas in Morocco that boast a higher than average rainfall, indeed among the highest in all of North Africa. An intensive mixed arboriculture has traditionally been the backbone of the rural economy, distinguishing it from the preference for cereal culture in the plains lying below the highlands. The rural economy in Roman antiquity appears to have shared this same distinction between highland and plains regions in this part of Africa. It is not accidental, I think, that the one detailed epigraphical text suggesting agricultural development in the lands near Thullium concerns a Lucius Arrius Amabilianus, an arboriculturalist. Like our Gaetulus, he was a flamen perpetuus, probably in the same municipality of Thullium.Footnote 17 The octogenarian Amabilianus boasts of having established his domus and having improved its economic well-being. He laid out an orchard with apple trees and provided it with a well, and then he set out a second orchard of fruit trees that he furnished with a water reservoir and a well. Amabilianus was another hard-working bonus agricola of the time who rightly boasted of the improvements that he made to his patrimony.Footnote 18 Arboricultural crops appear to have been the ones of which he was especially proud.

Figure 4.2 The Hippo Regius Region: Hippo Regius and Thullium.

Since both Gaetulus and Amabilianus held municipal priesthoods, we might ask when and how the municipalization of the region, and therefore of Gaetulus’ home town of Thullium, took place. Far to the northwest an Augustan colony was established at Hippo Regius, and a little further away to the south the Flavian emperors founded a colony of veteran soldiers at Madauros. But these were exceptional Roman settlements made by the direct intervention of the Roman state. Otherwise, Thullium was right in the middle of a zone that was remote in terms of Roman municipal development. The closest municipal centers were located on the periphery of a fifty-mile radius extending outwards from Thullium: Hippo Regius to the northwest, Thuburnica to the southeast, and Thagaste to the southwest. There was no known move to formal Roman municipal status made by any of the towns in the Cheffia highlands throughout the whole period of the high empire. We must therefore suspect that the advancement of Thullium to formal municipal status took place – if it happened at all – in the later empire.Footnote 19 Just how far the forming of municipal institutions eventually proceeded and what the process meant in the highlands is difficult to say. A comparable village in a similar highland environment at Henchir Aïn Tella (ancient Castellum Ma […] rensium), in the far western Khoumirie to the north of Thullium, was still governed by seniores or a council of elders as late as the age of the Tetrarchs.Footnote 20 Generally speaking, then, it seems that the communities in the mountainous highlands from which Gaius Julius Gaetulus came were not as intensely connected with the main patronal resources of the empire. They were not able to develop the costly apparatus of urban Romanity sufficiently to convince governors or emperors that they were worthy of elevation to colonial or municipal status. In this fashion, the political ecology of the region determined elements of the identity of its inhabitants.

If the important colonial harbour city of Hippo Regius was only about forty kilometers from Thullium as the crow flies, the experiential distance was considerable. The accidence of the terrain and the heavily forested environment contributed to a palpable sense of difference from the metropolitan world of a well-connected Mediterranean sea port. Even within the Cheffia, Gaetulus’ village of Thullium was a satellite outlier, being located towards the northwestern periphery of the region. As such, it was much closer to the outer eastern periphery of the Hippo Regius region than to the subzone of the Bagrada (the modern Medjerda) river valley to the south. If Thullium was most probably still a simple civitas at the time that Gaius Julius Gaetulus served in the army, we know that its inhabitants were gradually adopting Roman norms. Formal municipalization was slow, only coming in the later empire when similar small towns were achieving higher status in the flush of what can be called a late imperial rural ‘boom economy’ in Africa. In the early fifth century, the village was known to Augustine, the Catholic Christian bishop of Hippo. He referred to Thullium and to a man there with the African name of Kurma who was a curialis of the municipality.Footnote 21 Augustine’s words are rhetorically construed (for him, Kurma’s unusual life-and-death experience was being used as an example), but they strongly suggest that to be a member of the town council of Thullium and to be in the ranks of its duoviri did not require particularly great wealth.

The ethnic group of the Misiciri to which Gaetulus belonged is one of the better-attested ‘tribal’ entities in Roman-period North Africa.Footnote 22 By studying the distribution of inscriptions in both palaeo-Tamazight and Latin, or ones that were bilingual, using both languages simultaneously, it is possible to plot the region in which the people who identified themselves as Misiciri lived. Their distribution on a map (see Fig. 4.3) shows that their region was a zone between the Bagrada valley and hilly lands to the south and the coastal plain inland of Hippo Regius to the northwest. If there were long-term interactions between the inhabitants of the Cheffia and their environment, it is hardly surprising that they came to share common identities. The peoples inhabiting the region would have shared a common distinctive environment in which they lived and worked. The larger montane zone consists of distinctive subzones, and so it is speculatively possible to identify five major subgroups of which the Misiciri were formed and to map their locations in the highlands of the Cheffia.Footnote 23 The concentrated location of inscriptions belonging to each subgroup argues in favor of an ecological component in its formation and identity. Each seems to be located within a fairly well-defined territory that was formed by a valley – that is, by distinctive mountain and riverine confines.Footnote 24 What is more, if the ecology of these regions in the Roman past resembled that of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (which I have no reason to doubt), then the dense habitation of the mountain highlands was matched by an intense fragmentation of ethnic identity. In addition to the five subgroups of the Misiciri, seven other ethnic groups have been identified in the highlands immediately adjacent to the Cheffia. Most probably, like the subsections of the Misiciri, they were local groups of the much larger peoples collectively named the Numidae.Footnote 25

Figure 4.3 Proconsular Africa: The ‘Cheffia’ Region in Context.

Having been raised in this ecology, who was our Gaetulus? Was he was a high-ranking Roman citizen, a soldier in the Roman army named Gaius Iulius Gaetulus? Or was he Keti son of Maswalat from the tribe of the Misiciri, from the subtribe of the S’RMMi? Almost certainly he was both at the same time. He was like the man from Gaul who boasted on his tombstone found at Aquincum on the Danube: “I am a citizen of the Franks and a Roman soldier under arms.”’.Footnote 26 Like many Gauls and Germans serving the empire, this man maintained a bifurcated identity. One was local and the other imperial, the second being determined by the existence of the empire and its army. Gaius Julius Gaetulus was like the Roman citizen from Tarsus who called himself Paulus. Several times Paul insisted on his possession of the Roman citizenship before high-ranking officials of the imperial state. At the same time, he was Saul, a man who self-identified before his fellow Jews as Jewish, a descendant of Abraham from the tribe of Benyamîn, and belonging to a family of strict Pharisaic upbringing.Footnote 27 A special aspect of Gaius Julius/Keti’s split identity is that it was not new to him. It had been maintained over a number of generations. The original citizenship of Gaetulus’ remote male ancestor, and hence Keti’s own praenomen and nomen of Gaius Julius, almost certainly dated to the time of Julius Caesar. That ancestor had probably received land and citizenship from the great generalissimo in the mid-40s BCE as a reward for military service. A precise date for our inscription is difficult to specify with any certainty, but we have argued earlier that some point in the early to mid second century makes the most sense of all of the evidence. If so, our Gaetulus was part of a family that had connections with individuals and institutions that were Roman for about two centuries (possibly more if there were Marian antecedents in his line of armed service). But let us say, provisionally, that we are looking at approximately two centuries. Assuming an arbitrary calculation of about thirty years to a generation, our Gaetulus was part of a family whose service connections with Rome (or, at very least, Roman citizen identity) had continued through no less than five to six generations. We are fortunate to have evidence of another man from Thullium who did army service and who also bore the name of Maswalat. Having served in the Roman army, like our Keti, he is similarly called a ‘servant of the great chief’ (i.e. the Roman emperor). There is a considerable likelihood that his Roman name was also Gaius Julius. If not these names, however, he surely bore the Roman tria nomina. But this Maswalat, despite having had the same army service as Keti, had all of his identity recorded solely in his native language and in words taken from his own African tongue to describe his imperial service.Footnote 28

As shown previously all by his army service, our Keti was also a Roman. Indeed, as has been acutely observed, in this respect he could hardly have been more Roman.Footnote 29 Yet in his native language he chose to present himself as an African who belonged to an ethnic group, the Misiciri, and more specifically to a smaller subgroup of the Misiciri, the S’RMMi. Such men who performed imperial service, and persons related to them, added the cognomen Gaetulus, Gaetulicus, or variants to their Roman names and were proud of it.Footnote 30 The problems with our Gaetulus, however, are not so easily solved. Without doubt, during all of the years that he served in the army, he would have forefronted his imperial identity. He would ordinarily have spoken Latin and he would have been committed to the military values that enabled him to win the honors that he did. If he enlisted at the usual age of 18 to 20 and received a normal honesta missio, Gaius Iulius Gaetulus would have returned to his home town in his mid forties. He died at the age of 80, so more than half of his adult life was lived not in the Roman army but back home in the highland society of the Cheffia. In this context, inherited aspects of his behavior, inculcated from infancy and early childhood, like the native language that he spoke, would have come back into play in his daily interactions with the local people with whom he now lived. Who our man was depends very much on the time when we are considering his personhood. Was army service a usual gateway to imperial membership for men in these highlands? We are fortunate to know of other cases precisely like Keti’s. There were, for example, several known men from the same region who bore the name Iasuchthan: from the highlands around Mactaris to the southwest of the Cheffia, but also in the Cheffia itself.31 A man most probably from our region, also bearing a ‘republican’ praenomen and nomen, Marcus Porcius Iasucthan was a centurion serving in the Roman army who left record of his service at the distant desert post of ad Golas (modern Bu Njem, Libya) in the 220s CE.32 The long metrical poem erected at Iasucthan’s behest is filled with indications that for him Latin was manifestly a second language.33 At least in terms of language, but probably much else, Iasucthan shared the same kind of double identity as did Keti son of Maswalat, and this some three generations later.

That a culture and therefore a personal identity is confirmed and continued by the inculcation and adoption of a language goes without saying. Language is a verbal and written encoding of the canons of a culture taken on by humans from birth without their assent or permission. What is significant about the region that Keti came from is that it gives all of the appearances of being a particularly strong container of indigenous African cultures and languages. By contrast, the lowlands and plains areas below the Cheffia seem to have been caught up in a series of large-scale economic acculturations led by Punic city-states in Africa that led to the proletarianization or transition to peasant agriculture by the local farmers.Footnote 31 Through the years of the high empire and into late antiquity, the rural dwellers in these lowlands continued to speak Punic as their primary or first language. In the highlands, however, where this economic shift did not take place, the inhabitants apparently continued to speak various dialects of native African languages that we rather misleadingly call Libyan, but which were most probably distant ancestral forms of Tamazight. The reason that we know this is because of truly striking concentrations of inscriptions. Almost all of them are on funerary stones, written in a script developed to write the local language, as a form of writing that was distinctively different from the Punic and neo-Punic scripts used to write ‘Punic’ or the Roman script that was used to write Latin.Footnote 32

Better to understand the physical and social context, we might reconsider the position of Thullium in comparison with the small village of Fussala. Fussala was equidistant from Hippo Regius, probably located about 15 to 20 km southwest of Thullium. We know that the first language spoken at Fussala, indeed practically the only one spoken by the majority of the peasant farmers in the region, was some form of what we (and the Romans) call Punic.Footnote 33 The palaeo-Tamazight speakers of the highlands, who lived in places like Thullium, had a linguistic buffer zone of non-Latin speakers placed between them and the large imperial urban center of Hippo Regius and the plains region immediately adjacent to that city. It would have been a rather permeable buffer, however, since it is likely that there was a greater linguistic proximity between palaeo-Tamazight and Punic, and related spoken languages, than there was with Latin.Footnote 34 Further nuances are evident, even within a small community like Thullium. Two separate cemeteries have been found in the village: one that contains gravestones with the palaeo-Tamazight and bilingual Latin/palaeo-Tamazight epitaphs, and a second one where the writing on the gravestones that do boast epitaphs (admittedly relatively few) is only in Latin.

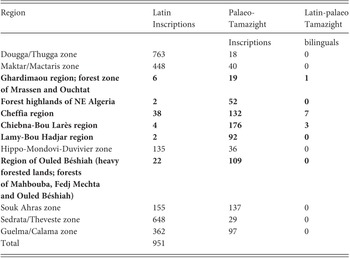

A basic and simple sign of empire in the highlands around Thullium was the pursuit of what has been called the epigraphic habit. It seems likely that the heyday of the production of epigraphical texts in non-Latin languages tracked the chronological arc of the production of Latin inscriptions for the same purposes, mainly funerary memorialization and the recording of public honors.Footnote 35 That writing in this particular script was used demonstrates a type of cultural continuity in which Gaius Julius Gaetulus must have shared. The palaeo-Tamazight script is found widespread across the entire face of Africa. Variants of it are found in distant Mauretania Tingitana far to the west and in the form of casual wall graffiti in lands much further to the east on the desert periphery of Tripolitania, perhaps significantly, in this latter instance, in connection with a Roman army base.Footnote 36 Perhaps even more important than the simple use of this script for interpreting Keti’s social position is apparent from the distribution of writing in all of the highland regions east of the Guelma/Calama line in North Africa (Table 1). Of all these zones, the subregion of the Cheffia is the only one where Latin/palaeo-Tamazight bilinguals are found. There are few of them, so there is every reason to believe that those who chose to have their final memorials recorded in both languages were themselves rather special cases. They were not special, however, in that they were surrounded by an unusually high number of palaeo-Tamazight inscriptions.

Table 1 Location of Inscriptions east of the Rusicade (Skikda) – Calama (Guelma) line

| Region | Latin Inscriptions | Palaeo-Tamazight | Latin-palaeo Tamazight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inscriptions | bilinguals | ||

| Dougga/Thugga zone | 763 | 18 | 0 |

| Maktar/Mactaris zone | 448 | 40 | 0 |

| Ghardimaou region; forest zone of Mrassen and Ouchtat | 6 | 19 | 1 |

| Forest highlands of NE Algeria | 2 | 52 | 0 |

| Cheffia region | 38 | 132 | 7 |

| Chiebna-Bou Larès region | 4 | 176 | 3 |

| Lamy-Bou Hadjar region | 2 | 92 | 0 |

| Hippo-Mondovi-Duvivier zone | 135 | 36 | 0 |

| Region of Ouled Béshiah (heavy forested lands; forests of Mahbouba, Fedj Mechta and Ouled Béshiah) | 22 | 109 | 0 |

| Souk Ahras zone | 155 | 137 | 0 |

| Sedrata/Theveste zone | 648 | 29 | 0 |

| Guelma/Calama zone | 362 | 97 | 0 |

| Total | 951 | ||

Lowland beliefs and religious institutions inflected the nature of local culture in the highlands of the Cheffia and therefore customs of burial and commemoration. Many of the iconic themes on funerary stelae – crescent moons, rosettes, caducei, crowns, and palm branches – are the same as ones conventionally found on the Saturn stelae of contemporary African cult in the Roman-type transformation of the cult of Ba’al Hammon. However pervasive these signs were on the cultic imagery found in the highlands, it was not for any engagement with the cult of Ba’al Hammon or Saturn that Gaius Julius Gaetulus was noted. Most significant is the fact that he came back to his home municipality of Thullium to hold the position of flamen perpetuus, the local priest in charge of the cult of the emperor. He was not alone. The ‘good farmer’ from this same region, Lucius Arrius Amabilianus, also held the same position, probably also at Thullium. Without large numbers or ways of tracking and quantifying all such ritual adherences, it is still notable that a few of the wealthiest and highest-status men were careful to note their engagement with the imperial cult. The position of flamen, which would have engaged the holder of the title in the annual celebration of the emperor’s birthday and the administration of public oaths of loyalty, was surely selected to emphasize Gaetulus’ Roman identity. He lived before the times when Christian ideas and practices were beginning to have wide influence in Africa. The emergence of Christian institutions at Thullium was probably roughly analogous to the pattern found at Fussala, located in the southeastern borderlands of Hippo Regius. There are some signs of Christian building activities in the Cheffia, including a chapel built at Bar el-Ghoula by a patron of the church, but they are rather few in number and do not seem to betoken anything like the comparatively intense Christian presence at lowland sites in the regions around the Cheffia.Footnote 37 From Augustine’s words about the ironworker Kurma, there appears to have been no Catholic bishop at Thullium in the first decades of the fifth century. Like the village of Fussala, Thullium appears to have been nested within the large Christian bishopric of Hippo Regius. Neither the acts of the general conference held at Carthage of 411 nor the Notitia of bishoprics of 484 indicate that there was any bishop, Catholic or ‘Donatist’, in the town. By the late Vandal period, however, Thullium had been able to assert its autonomy from the diocese of Hippo. There was a bishop of the Christian church from the town who was present at the conference at Carthage in 525.Footnote 38 From the point of view of the formalities of the Christian church, Thullium, like Fussala, was a late developer. Fussala got its own bishop as early as the 420s, whereas the establishment of a bishopric at Thullium was delayed by as much as eighty or ninety years later.

In the provinces of the early to mid second century, optative identities like being a Roman or, later, being a Christian were largely matters of personal adhesion. But language and kinship were not. You were born and raised with given ones. The largest social group named in inscriptions from the Cheffia, both in Latin and in palaeo-Tamazight texts, was called the Misiciri. They were members of a kinship unit who were present on a geographic and demographic level that covered most of the region. It was the largest African group to which Keti claimed to belong. But he also recognized a subgroup of the Misiciri, called the S’RMMI or Saremmi. Manifestly, they were a smaller and more specific kinship group, to which he also belonged. Arguments have been proffered that there were at least four other similar subgroups of the Misiciri that are attested in the palaeo-Tamazight inscriptions in this same region: the NSFH, NNDRMH, NFZIH, and the NBIBH.Footnote 39 Whether these were all the subunits of the Misiciri, and whether or not they confirm the existence in Roman period Africa of the ‘five-fifths’ segmentary systems found in some modern-day Amazigh groups in the Atlas and Rif far to the west, will need further investigation and discovery to confirm. It is sufficient to note here that the Roman Empire kinship identity in this region was nested in complementary segmentary units that had apparently existed for a fair period of time. These same nesting arrangements of kinship groups are attested for other similar ecologies in the Roman world. An inscription from Rawwâfa in northern Arabia records a temple built by a man, one Sa’dat, who identifies himself as from the Sisthioi, a subgroup of the Thamudenoi (Thamûd), and the Sisthoi themselves were from the ‘tribe’ (phylê) of Rhobathos.Footnote 40 Here is found the same trifold nesting of one ‘ethnic’ unit within another.

Furthermore, a gendered aspect of the public notation of ethnic identity is regularly discernible in the epigraphy of the region. In all the funerary epitaphs from the Cheffia, all of the females are identified with names that look very Latin. Not one of them is memorialized in the palaeo-Tamazight script or in a palaeo-Tamazight/Latin bilingual. No woman in any type of epigraphical text identifies herself as a member of any of the kinship groups in the Cheffia. In the public sphere, it seems that men, but not women, deliberately marked elements of traditional culture and ethnic affiliation. And yet there must surely be a strong presumption that indigenous women, as in many comparable instances in the western provinces of the empire, were special bearers of local identity, such as being a Misiciri or a S’RMMi. Apparently these women, who were surely in the majority, simply did not present themselves in the field of public epigraphy.

There is one strong qualifier to all of these observations on kinship and ethnic identity. Our man boasted the Roman Latin cognomen of Gaetulus. In Roman terms, there is no doubt that he was seen and classified as a ‘Gaetulian’. The problem is that there was almost certainly no ethnic group defined in terms of kinship (like the Misiciri, for example) that identified itself as Gaetulian. Such a term never appears in the indigenous palaeo-Tamazight script or in any contemporary epigraphical texts as the name of a distinct ethnic group.Footnote 41 The name appears to be an external identifier, one of the generic categories of ‘Africans’ that were used by imperial administrators, and by the geographers and ethnographers who provided them with ‘ethnic information’. The name seems to have emerged as a convenient label for a generic class of indigenous persons who happened to engage in armed service for the Roman state. Gaetulians were seen as a grab bag of sometimes southern, sometimes highland, sometimes autonomist, occasionally violent peoples. Various peoples who were occasionally involved in resistance to programs of settlement and integration that were fronted by Mediterranean states with which they came into contact were categorized as ‘Gaetulian’ regardless of their own self-ascribed ethnic identity. In defeating any people who fell under this external rubric, Roman generals assumed the ethnic name ‘Gaetulicus’ as a victory cognomen.Footnote 42 Many of the specific ethnic groups who fell under this external rubric were subsequently absorbed into the armed forces of the Roman state. Evidence of such armed service dates early into the pre-Roman past of the Carthaginian hegemony in Africa. We are told that Hannibal recruited Gaetulians for service in his army.Footnote 43 Men of this extraction formed a pool of potential recruits for armies whether they were Carthaginian, African, or Roman. Marius recruited important elements from ethnic groups called Gaetulian for his African campaigns against Jugurtha.Footnote 44 In the civil wars of the 40s, these same Gaetulians, along with Numidae, were recruited by the Pompeiani and served them until Julius Caesar, the descendant of Marius, appeared on African shores. At that point they defected en masse to his side.Footnote 45 In regions further to the west, around Cirta and Calama, other men of this same background went over to the side of Caesar’s self-appointed freelancing baronial ally, the Campanian freebooter Publius Sittius. It is very likely that many of the Africans who later bore the cognomen Sittius were among the Gaetulians who were enfranchised by Caesar’s man in the west.Footnote 46 It is similarly probable that the Gaetuli who loyally served Julius Caesar in the battles in the old Republican province of Africa in 46 BCE account for considerable numbers of men who were enfranchised by him. They later bore the praenomen Gaius and the nomen Julius, as our man Keti did many generations later. This particular Roman connection with the so-called Gaetulians deserves closer inspection.

In taking over command of the war against Jugurtha, Gaius Marius recruited heavily not just from among newly eligible Roman citizens in Italy but also from, as is often not noted as part of this same process, among ‘ethnic’ peoples in North Africa. These latter men also provided important additional manpower for the war against Jugurtha. Being well acquainted with local languages and customs and thoroughly experienced with the climate and terrain, they were perhaps among the most useful of Marius’ new recruits. He drew many of them from indigenous peoples living along the frontiers of the Republican province. When the war was over, he arranged land rewards not only for his Roman citizen and Italian veterans but also for his African soldiers. They were settled in towns and in rural regions in the same interstitial zone along the western border of the Roman province.Footnote 47 In Roman parlance, these Africans doubtless became his clients and were understood to be so, although surely no Roman technical term would have been necessary in the minds of the Gaetuli themselves to describe the social gratitude that linked them to their benefactor. They had served him, and now he had served them. As was traditional, they assumed close ties of loyalty by kinship and military service with Marius’ descendants. In the factionalism of the civil wars that rent Africa in 46 BCE, it was natural that the descendants of Marius’ Gaetulian recruits rallied to support Julius Caesar, who was Marius’ close familial relation, against his personal enemies, the Pompeiani. In response, Caesar had extended the citizenship to these men and had made grants of land to them.

In consequence we encounter many descendants of these Gaetulians in the high empire who bear the praenomen Gaius and the nomen Julius.Footnote 48 Several generations after the age of Caesar, we find cohorts of Gaetulians in the service of the Roman army. One of them, the Cohors Prima Gaetulorum, is reasonably well documented.Footnote 49 The geographic distribution of the cognomen ‘Gaetulicus’ reveals heavy concentrations just to the west of the old provincial boundary, the Fossa Regia, one of them in eastern Numidia where Keti’s home town of Thullium was located. Most of the other groups of men bearing the cognomen of ‘Gaetulicus’ were connected with various army bases in Africa, including Ammaedara, Theveste, and Lambaesis. Such men are also found concentrated in colonial settlements of veterans, like Madauros and Thubursicu Numidarum.Footnote 50 There are good reasons to believe that Marius was responsible for the settlement of his African veterans who would otherwise have been labeled as Gaetulians but who, after their receipt of citizenship, bore the praenomen Gaius and the gentilicium Marius. Significant numbers of the descendants of such men are found in the borderlands of the old republican province in Africa: that is to say, in lands south and east of the Fossa Regia. The distribution manifestly points to the pattern that we would expect from the historical scenario just described.Footnote 51 As with the men and women who later have the cognomen Gaetulicus, or variants like Gaetulus, those bearing the praenomen-nomen Gaius Marius when they are found outside the core area to the west of the republic province in Africa, are also attested in the big army camps or in veteran colonies.

All these facts indicate that army service continued to define who these men were over several generations. Gaetulian was manifestly an external Roman label used to cover such armed servitors. The men themselves, however, had their own local identities: for some of them it was that of belonging to the Misiciri. To use the name of Misiciri, however, only raises further questions of identity and representation. The Misiciri were just one of a number of small ethnic groups lying south and west of the frontier of the old province of Africa from whom the Roman state continued to recruit in the empire. Men from smaller local groups like the Misiciri were usually recruited under larger headings, being considered Gaetuli, Afri, Musulamii, Numidae, or the like, for the administrative purposes of the Roman state. Men in all of these groups continued to contribute manpower to the auxiliary units of the imperial army. Many of the Gaetulians who were already Roman citizens from the days of Marius and Caesar, however, were eligible for direct entry into the legions of the imperial army. This historical background and the claims with the Roman state that could be based on it are significant. In the wider context of the empire, it is manifest that there were firm ethnic prejudices held by the big power holders, against Gauls and Germans and other northerners for example, that were effective barriers to advancement in the imperial system.Footnote 52 Even for Gauls and Germans, however, a gateway into the ranks of imperial power – and one that became dominant for excluded northerners from the early third century onward – was through service in the army.

This is the role in which we find our Gaius Julius Gaetulus at Thullium, and most likely not a few of the other men whose gravestones we find in the Cheffia – men like Lucius Postumius Crescens, also from Thullium. Crescens was remembered not just in Latin on his memorial stone, but also in a parallel inscription in palaeo-Tamazight where he self-identified as belonging to the Misiciri, probably assuming that everyone knew that his being one of the local S’RMMi was understood.Footnote 53 There were others who, like Nabdhsen son of Cotuzan, noted that he was from the tribus Misiciri. Perhaps because he died at the age of twenty, Nabdhsen never made it into active army service. This is the only information that appears in Latin in Nabdhsen’s epitaph. But the words in Latin are accompanied by a parallel inscription in palaeo-Tamazight which shows that, like Gaetulus, Nabdhsen also identified himself as a member of the S’RMMi.Footnote 54 Nabdhsen probably shared a status similar to Sactut son of Ihimir who was also memorialized in a parallel palaeo-Tamazight inscription on his tombstone.Footnote 55 Such was probably also the case with Chinidial son of Wisicir from the tribus Misiciri from a site just to the southwest of Thullium, whose Latin epitaph is also accompanied by one in palaeo-Tamazight. In this case, interestingly, the text in the indigenous script does not say that he belonged to the Misiciri but rather to the NChPi, who, like the S’RMMi, were most probably a smaller subgroup of the Misiciri.Footnote 56 Chinidial therefore preferred to note his membership in the small kinship group, assuming that everyone understood that the NChPi were a subgroup of the Misiciri. On the other hand, one Paternus son of Zaedo, like our Gaetulus, is named as a member of the Misiciri only in the palaeo-Tamazight text on his stone, as is another son of the same father in the same town.Footnote 57 Similarly, one Aug[e?] son of Sadavo, Numidian from the tribus Misiciri, includes his affiliation with the larger ethnic group as a significant element of his identification.Footnote 58 An important ancillary point revealed by the nomenclature of these men is that the default mode of ethnic identity in the highlands of the Cheffia shows no sign of any obvious Punic influences. These personal names are not cast in a formal Roman Latin mode; they are Latin transcriptions of African names. Nabdhsen, Cotuzan, Chinidial, Zaedo, Auge, Sadavo, and so on, are not Punic names but African ones – just like the Kurma from Thullium who was mentioned by Augustine. This much is evident from other regions in Africa, where some locals who also had the praenomen -nomen Gaius Iulius, like Gaius Iulius Arish and Gaius Iulius Manulus from Calama (modern Guelma), adhered rather to the use of the Punic language and to the worship of Lord Ba’al.Footnote 59 They are two examples of Africans from non-highland areas whose culture had become Punicized before becoming Roman.

Through a series of ingenious and insightful parallels, it has been shown that the palaeo-Tamazight on Keti’s funerary stone reading MWSi MNKDi probably means something like ‘servitor of the supreme chieftain/king’. This was a local Misicirian way, so to speak, of describing Keti’s service in the Roman army. Several of the Latin bilingual speakers in the Cheffia, including our man Keti/Gaetulus, Postumius Crescens, and Sactut son of Ihimir, were army veterans.Footnote 60 For them and, we must suspect, for many others like them, the army was one of the main instruments of imperial integration and identity. The social and disciplinary regimes in the hothouse of the legion and the auxiliary formations helped to shape an identity vitally linked with the empire.Footnote 61 The role of the uniform requirements of a type of a national military service in forming identity was surely as significant here as it has been in many modern instances.Footnote 62 While the majority of recruits of the Legio III Augusta in Africa seem to have come from the more densely populated urban centers of the old province of Africa, especially from their urban proletariats, recruiting also continued from ‘ethnic zones’ of the African provinces. Many of the non-citizen recruits from these social groups probably gained citizenship and the ability to enroll in the legionary forces of the empire through auxiliary service in one of the units of Afri, Mauri, Numidae, or Gaetuli that are well attested in the auxilia of the high empire. The recruiting of highland peoples, whether the Ituraeans in the Lebanon, Thracians from the Balkans, or Isaurians from southern Asia Minor, was as normal. It was as typical as it later was for the armies of early modern Europe for whom military service by Scots, Swiss, Auvergnians, Pyrenaeans, or other impoverished highland men was normal. We can therefore say that armed service for the Roman state was a choice that a young man like Keti might make. The rider is that the Roman army as specifically configured in the late Republic and Principate had to exist as a viable institution for men like him to be able to make such a decision. Even given the availability of army service, the degree of freedom of choice is still open to debate. Four or five generations of male ancestors of Keti’s had already been in Roman army service. Given the tendency for a behavior like this to be inherited, we might ask how much this element was an embedded element of our man’s ethnic identity. Did the peoples of the Misiciri who had performed armed service for the Roman state for generations, like the Nepalese Gorkhas, the Gurkhas of the British army, come to be defined by that service?

The empire consisted of many different types of social and political units. These included kingdoms, principalities, and baronies, followed by city-states of various types, conventionally labeled as ‘free and autonomous’ or wholly subject to the dictates of the states. There followed ethnic units variously known as gentes, nationes, tribus, or populi. Since the first of these political units tended gradually to be squeezed out by managers of empire who considered such quasi-autonomous entities to be incompatible with the fact of empire, it became conventional to view the empire, ideally, as an amalgam of ‘cities’ on the one hand and of ‘peoples’ on the other. Therefore one way of envisioning the imperial project is to see it as an entity composed of distinct modular units: ethnic peoples on the one side and cities or urban communities on the other. More of some were found in certain regions, and more of the others in others. Such a taxonomy was always complicated by the fact that urban groups were themselves sometimes construed as ethnic groups, as, for example, the Cirtenses, Madaurenses, Thuggenses, and the Capsitani in Africa. A different way of thinking about the same process would be to see this divided composite of identity as potentially running internally through individual subjects all the way down to the ground level of any given locale. There is every reason to believe that the empire was filled with persons of such divided identity. The one individual case of Keti son of Maswalat powerfully indicates how moveable and changeable some of the elements were that contributed to ethnic identity in this mix. Mommsen long ago made a fundamental observation that is worth repeating: the empire was a continuous revolution, a thing always in the process of remaking itself. The effects of this continual refashioning were felt at local level. In this hybridity, there are some elements that seem more stable or longer term than others, but change was ever present.

Anchoring one end of this polarity were long-term, almost inherited aspects of identity that surely had a large impact on how the person saw himself or herself. Of these, the inculcation and learning of a native language must be one of the most formative, even in a multi-lingual environment. There is no reasonable doubt that a variant of proto- or palaeo-Tamazight was spoken in the highlands to the east and south of Hippo Regius and that it was in all likelihood Keti’s language of birth. Since the region was surrounded and, to some extent, penetrated by native speakers of Punic, we might suspect that Keti might have acquired knowledge of this other language, especially given its closer relationship to his native tongue – that is, when compared to Latin. The odd thing, perhaps, is that the palaeo-Tamazight speakers in the region developed, adopted, and propagated an idiosyncratic script of their own in which to write their language in public. This cannot be accidental. The continued use of a distinctive and peculiar script that first appeared in these regions, broadly speaking, with the first African kings must have been a deliberate choice. Both of these facts distinguished this propensity from the speaking of Latin. Although the inscriptions in the Cheffia highlands belong to a relatively restricted Roman time frame, nonetheless the script has a known time span that had already covered about three centuries or so by the time that Keti’s relatives were using it for his funerary epitaph.Footnote 63 On the other hand, from prolonged army service, if nothing else, Gaius Julius Gaetulus would surely have acquired a reasonably good command of Latin. Even if learned and even if a second or a third language, the language of empire was present in relatively remote villages and hamlets like those of the Cheffia.

Our Gaius Julius Gaetulus or Keti son of Maswalat belonged to the peoples of the Misiciri and the S’RMMi. And he might even have considered the Gaetuli to be some larger such notional kinship-like entity to which he also belonged by virtue of the fact that the Misiciri were labeled as Gaetulians by the Romans whom he served. But he was also a Roman citizen of a family who had been Roman citizens for many generations. He was a citizen of the great imperial metropolis of Rome as also of the town, perhaps municipality, of Thullium. The managers of empire must have been aware of how normal a circumstance this was in the formation of their state. As we have said, one ideal way of reading the standard claim that the empire was made up of ‘cities’ and ‘peoples’ was to stress the existence of different and exclusive categories of social groups out of which the empire was composed: cities on the one hand and peoples on the other. The empire is made of apples and oranges, chalk and cheese. On the other hand, the concept could be understood as indicating a different sort of composite of which the empire was made in which individuals were simultaneously members of cities and also of peoples, like our Gaius Iulius Gaetulus/Keti son of Maswalat.

Of course, it is not possible finally to sort out something as complex as ethnic identity on the basis of a few inscriptions, some scattered literary references, and a few comparative data. But at least the following seems reasonably certain: even after many generations of integration into the parallel apparatuses of the Roman state, an apparently Roman man who served a lifetime in its army and in its municipal institutions still maintained a separate African identity. And he was not alone. The nomenclature of other persons in the Cheffia, the widespread use of a palaeo-Tamazight script, and the presence of stereotypical units of common ethnicities indicate a general social system of which he was part. Demonstrably in his case, and probably in the others, this local African culture was a living fact over a significant number of generations. This vibrant cultural world and the language in which it functioned was not a choice in the formation of Keti’s identity. There were also other elements that were outside free choice, and one of the big ones, surely, was the sea change in shape and structure that the Roman Empire went through in the late third and early fourth centuries. In Africa, as elsewhere, the third-century crisis of the empire was a crisis for ethnic identity. It is an observable phenomenon on the southern frontier of the empire, as well as on and beyond its northern ones. A host of identifiable ethnic groups entered this crisis and then disappeared from view. In the mid third century and at the end of it, new groups and new identities emerge. Very few of the old ones made it through the crisis unscathed.Footnote 64 The Gaetuli and Gaetulians, like our Gaius Julius, disappear from the record, as do the Misiciri and, needless to say, the S’RMMi and the other four subgroups of the Misiciri of whom we know from the high empire.Footnote 65 In some sense, it seems, these groups had their identities confirmed and maintained by being part of an imperial system that recognized them as being a specific people and that continually underwrote that identity by an administrative computation and by a specific type of integration within the empire – in the case of the Misiciri by armed service. When that system profoundly shifted in structure, so did the ethnic identifiers that were part of it.

On the other hand, there is no reason to diminish the Roman parts of Keti’s identity: his knowledge of Latin, Roman citizenship, municipal service, and Roman name. All of these elements, and the values associated with them, had also been maintained by his family over several generations. These other Roman elements of his identity, however, required the continued presence of the empire, indeed a particular type of that empire, to sustain them. Without an imperial army that entailed specific kinds of recruitment, integration, training and service, there are serious questions whether much of the imperial identity would have taken hold among the men of the Cheffia in the way that it did. As long as those specific connections existed, however, the case of Keti points to the presence, in non-trivial numbers, and in considerable parts of Africa of persons with this type of split identity. And there are surely good reasons to suspect that Keti son of Maswalat/Gaius Julius Gaetulus was a typical figure of empire. Everywhere we look, from the Gaulish noblemen in the west to persons like Saul/Paul in the eastern provinces of the empire, we witness the same inside schism that ran along the internal fault line between local society and central state.Footnote 66 The different strands in personal identities ran from the top to the bottom of the social orders of the empire, confirming in reality the ideological claim that the Roman Empire was an empire of cities and peoples. Frequently, we must suspect, it was so within each person. It was an ever-changing, ever-adapting social schizophrenia that was maintained over many generations in not a few of the provincial families in the empire. It was as essential a characteristic of empire as were the elements of its grander political unity.