The legal theory of post-war German counter-revolutionists was decisively influenced by international events and the concept which permitted an unlimited sovereignty to ignore international law is the source of the theory that political activity is not subject to legal regulation. This was the presupposition for the theory of the Prerogative State.

These are difficult times. Populist and authoritarian leaders are dismantling rule-of-law norms domestically, and they are working to do so internationally. Although political actors increasingly deploy rule-of-law discourse, they frequently abuse it to legitimate authoritarian rule, often in the name of law and order. How to measure these shifts is a challenge given the variety of institutional means to advance or undermine the rule of law, yet both qualitative and quantitative analyses indicate overall declines in rule-of-law protections transnationally, which are essential for individuals to lead lives not subject to domination.

We conceive of the rule of law as an ideal – or meta-principle – under which individuals are not to be subject to the arbitrary exercise of power. We examine the interaction of domestic and international factors in eroding the rule of law, including the rise of populist, authoritarian leaders in traditionally democratic countries, the intensification of repression in existing authoritarian regimes, and the relative decline of Europe and the United States in relation to an authoritarian China and other emerging powers. These shifts weaken the diffusion and settling of rule-of-law norms within states, which, in turn, affects normative development and institutional practice internationally. They also are generating robust responses that we evaluate.

Challenges to the rule of law raise a series of conceptual and empirical questions that are transnational in their scope and implications. This introductory chapter is in five parts. Part I explains our conceptualization of the rule of law, necessary for the orientation of empirical study and policy responses. Following Martin Krygier, we formulate a teleological conception of the rule of law in terms of goals and practices, which, in turn, calls for an assessment of institutional mechanisms to advance these goals given varying social conditions and contexts. Part II sets forth the ways in which international law and institutions are important for rule-of-law ends, as well as their pathologies, since power also is exercised beyond the state in an interconnected world. Part III examines empirical indicators of the decline of the rule of law at the national and international levels. It notes factors that explain such decline, and why such factors appear to be transnationally and recursively linked. Part IV discusses what might be done given these shifts in rule-of-law protections. It responds to the Biden administration’s rallying of a coalition of democracies to combat authoritarian trends at home and internationally, and it assesses tensions between political and economic liberalism. We then conclude in Part V, noting the implications of viewing the rule of law in transnational context for conceptual theory, empirical study, and policy response.

I Conceptualizing the Rule of Law: What’s the Point?

We develop concepts because they are useful for understanding the world and intervening within it. The starting point for developing the concept of the rule of law is to assess what is at stake for individuals and the communities of which they form part – that is, what is the problem that the rule of law aims to address. We start with Krygier’s conception of the rule of law in terms of social goals and practices, after which we turn to different normative and institutional means to advance these goals. It is both the ends and the means that can – and must – be assessed empirically to inform any effective response.

We posit that the rule of law is a normative ideal that should be viewed teleologically in terms of its ends. The goal of the rule of law is to oppose the arbitrary exercise of power by setting boundaries on, and channeling, power’s exercise through known legal rules and institutions that apply to all.Footnote 3 The rule of law aims to limit, through legal rules and institutionalized practices, the exercise of power by some persons over others. Arbitrary power can be terrorizing. People internalize its threat.Footnote 4 Through self-suppression and self-protective collaboration, individual freedom and civil society wither. The goal is thus to create restraints on government, as well as private power, together with channels for cooperative and coordinative activities,Footnote 5 which provide security and predictability so that people can plan and organize their pursuits and do so without fear. Power can be used for good or ill. For us, as for theorists ranging from Judith Shklar in the last century to Montesquieu earlier, “the fear of violence and the threat of arbitrary government provide an essential context in which the rule of law takes its meaning.”Footnote 6 As a goal, the rule of law is best viewed as a principle and not simply as a set of rules, because rules can be manipulated to subvert goals.Footnote 7 As an ideal, the rule of law will never be fully attained given human failings, but that does not make the principle any less important. In this chapter, we focus predominantly on public power, while noting that effective state power also is required to temper the arbitrary exercise of private power, particularly as states delegate and outsource traditional public tasks to private actors.Footnote 8

Ultimately, for the rule of law to become effective, it must be institutionalized as part of a culture of conduct. It must become a practice.Footnote 9 It is for this reason that we apply a broader conception of law that includes institutionalized practice.Footnote 10 From a socio-legal perspective, the rule of law provides restraints on arbitrary state and private behavior through norms that enable people to reasonably know what is required of them, what is prohibited, what they may do, and what can be done to them, combined with the institutionalization of these norms so that they “count as a source of restraint and a normative resource.”Footnote 11 These restraints facilitate the advancement of multiple social goals.Footnote 12 Where institutionalized, the rule of law becomes a habit or routine.Footnote 13

A teleological perspective reasons both forward in terms of an ideal, and backward in light of experience. It is the history of the arbitrary exercise of power, the real experience of abuse, that inspires conceptualization, empirical study, and social intervention. Our study of the rule of law is a legal-realist one, grounded in practice and experience and not in deductive reasoning.Footnote 14 Pragmatically, we know the value of the rule of law through historical and contemporary experiences of the arbitrary exercise of power. But our study is also based on a goal and purpose, or – to use the terminology of the pragmatist John Dewey – an “end in view.”Footnote 15

Before developing our argument regarding the rule of law from a transnational perspective, some caveats are in order. First, the rule of law is obviously not enough by itself and needs to be understood in relation to other social and institutional goals and practices. People and societies pursue multiple “goods,” including the satisfaction of basic human needs to enhance individual autonomy to make choices. As Michael Oakeshott writes, the rule of law “bakes no bread, it is unable to distribute loaves or fishes.”Footnote 16 Yet, the rule-of-law conception used in this chapter has powerful ties to theories of liberty based on furthering people’s real-life capacities. It contributes to a vision (in Amartya Sen’s terms) of “expanding the real freedoms that people enjoy,” thereby expanding their capacity to make choices in furtherance of what they value.Footnote 17 People are thus better situated to resist domination, from a republican perspective, and protect their autonomy from the arbitrary exercise of power.Footnote 18 The rule of law, in this sense, can be viewed as a complement to other (nonlegal) means of tempering power, and thus as supportive of this broader ideal.

Second, from a critical perspective, the pursuit of the rule of law is also linked to the substance of law. When only the powerful determine law’s substance, adherence to rules is less a matter of choice and more a reflection of power relations. Democratic participation in the determination of law’s substance is thus a necessary complement to rule-of-law ideals.Footnote 19 Contestation over the content of rules is a critical dimension of a robust, inclusive society protected by the rule of law.Footnote 20 The relation of the rule of law to democracy is complex.Footnote 21 Rule-of-law norms can be, and have been, advanced outside of democratic governance to different degrees in certain areas,Footnote 22 and democratic governments can exercise arbitrary power and claim democratic legitimation to do so. Illiberal democracies have proliferated, as illiberal governments borrow from each other’s playbooks to exercise power arbitrarily.Footnote 23 Their aim is to use rule-of-law language for their own illiberal ends.

The principles of democracy and the rule of law respond to different but interrelated questions and social problems. The issue of democratic governance poses the question of who exercises power. Rule-of-law concerns examine the question of how power is exercised.Footnote 24 Democracy and the rule of law nonetheless are related – even though, at times, in tension – since the rule of law provides a check and counterbalance to the unbridled exercise of power through majority rule. To start, the rule of law is a necessary condition for democracy. It is needed to assure that officials impartially conduct elections and count votes. In addition, the rule of law protects individual autonomy from domination so that citizens may freely participate in public processes that, in turn, affect them. As Jürgen Habermas writes, “on the one hand, citizens can make adequate use of their public autonomy only if, on the basis of their equally protected private autonomy, they are sufficiently independent,” and “on the other hand, they can arrive at a consensual regulation of their private autonomy only if they make adequate use of the political autonomy as enfranchised citizens.”Footnote 25 Both constitutional democracy and the rule of law provide institutional checks as moderating mechanisms that disincentivize the exercise of arbitrary power.Footnote 26 Because they serve as complements, they often rise and decline in parallel, as Part III shows.

Third, there is a long tradition of socio-legal and critical scholarship assessing the role of capital, class, race, and other attributes where law helps to constitute unequal social relations. As Robert Gordon writes, “legal relations … don’t simply condition how the people relate to each other but to an important extent define the constitutive terms of the relationship, relations such as lord and peasant, master and slave, employer and employee.”Footnote 27 For many scholars who criticize the liberal tradition, the rule of law is viewed more in terms of establishing “order” through the legitimating mechanism of law and legal institutions than “justice” in any substantive sense.Footnote 28 They are rightly wary of how law can mask, normalize, legitimate, and maintain unjust social relations. Within democracies such as the United States, minorities have been systematically subject to greater rule-of-law violations, whether formally under slavery and Jim Crow laws in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, or in institutional practices today in criminal, immigration, public health, and other areas of law.Footnote 29 Similarly, at the international level, critical scholars assess much of international law as a remnant of colonialism and imperialism.Footnote 30 Historical studies depict how colonizers exercised power under law to establish order and legitimate rule,Footnote 31 although clearly in violation of this book’s conception of the rule of law.Footnote 32 Those in power in postcolonial states likewise can deploy colonial forms of state control in the name of the rule of law to dominate their populations.Footnote 33

These critiques support conceptualizing the rule of law in terms of its goals – its point – and differentiating the ends from any particular formal and substantive means to attain it. It is thus important to distinguish the “rule of law” from “rule by law” and not collapse them into a single formal concept of “legality.” Governments around the world embrace rule-of-law rhetoric while instantiating a “rule of some groups over others by and through the law.”Footnote 34 “Rule by law” implies that those holding the power to make and enforce legal norms do so to regulate and control the population, while those who govern are not themselves subject to the rules that they impose. The rule of law requires that both the governed and those who govern are subject to the same rules so that all are protected from the arbitrary exercise of power. It is distinguished from rule by law both in terms of purpose and consequence. Conceptualizing the rule of law in this way, and differentiating it from rule by law, clarifies how law – whether local, national, or international – can be used for good or ill, can curtail and temper, or support and legitimate, the arbitrary exercise of power.

The rule of law and rule by law are ideal-type constructs. In reality, “arbitrariness comes in degrees,” and practices vary along a continuum.Footnote 35 State practices vary across issue areas and as regards different populations. Singapore operates as a “dual state,” Jothie Rajah writes, “in that it matches the ‘law’ of the liberal ‘West’ in the commercial arena while repressing civil and political individual rights.”Footnote 36 In this regard, Singapore, given its economic success, can serve as a model for other authoritarian regimes that wish to attract domestic and transnational investment. Relatedly, Tamir Moustafa and others theorize how authoritarian regimes often provide for pockets of judicial independence for different functional reasons, including for controlling administrative agents.Footnote 37 The rule of law also can be applied variably to different populations. Michael McCann and Filiz Kahraman document how the US legal system has long operated as a “dual state” for Blacks and other minorities,Footnote 38 while Eric Foner describes the United States in the Jim Crow South as “a quasi-fascist polity … embedded within a purported democracy.”Footnote 39 Ji Li similarly assesses variation in rule-of-law protections in China as a function of the issue and parties in a dispute.Footnote 40

A central reason to define the rule of law in terms of goals and practices is the risk of creating formulaic checklists based on specified, formal characteristics. Authoritarians have become proficient in adopting formal institutions deemed important for the rule of law, but which – in practice – serve to subvert it, and replace it with the rule of a particular party, faction, or person that rules by law. Many scholars, moreover, tend to derive these checklists parochially from their own legal traditions – particularly European legal traditions – and not others. Countries can produce quite different sets of rules for regulating social life in furtherance of rule-of-law principles. As Laurence Rosen writes regarding Islamic conceptions of the rule of law: “One need not, therefore, be an unrepentant relativist or a claimant of universal values to nevertheless respect the organizing principles by which others place limits on power and treat one another with that degree of consideration to which they would expect any valid system of law to treat them as well.”Footnote 41 Similarly, Makau Mutua stresses that Western concepts should not be simply transplanted to Africa, but rather varying cultural traditions and contexts must be recognized.Footnote 42 There are, in other words, a variety of means to advance rule-of-law goals, adapted to local traditions and conditions.

In practice, one must advance beyond goals to address means. It is at this stage, we maintain, that the concept of the rule of law becomes more contested.Footnote 43 One way to understand perennial debates over whether to adopt a “thin” or a “thick” concept of the rule of law is that scholars turn to different means for the protection of the goal of the rule of law. Proponents contend that these thin and thick conceptions provide particular “promise” for attaining rule-of-law ends.Footnote 44 Specifying different means is necessary, but they must be empirically evaluated with the end always in view, and they must be adapted to fit different social conditions and contexts that will vary over time and place.

Many focus on, and argue for, a “thin” concept of the rule of law that views it only in procedural terms. Many legal theorists adopt formal conceptions, such as the law’s generality, equality of application, and certainty. Lon Fuller notably advanced eight elements that constitute conditions for the rule of law (or, in his terms, “excellence toward which a system of rules may strive”). Law should be “general, publicized, prospective, clear, non-contradictory, compliable, consistently applied, and reasonably stable.”Footnote 45 Joseph Raz specified similar principles and divided them into two groups, the first focused on formal standards that provide certainty and predictability to guide action, and the second focused on legal machinery to make the first effective.Footnote 46 These proponents highlight the coordinative and channeling functions of legal norms in providing a framework through which individuals and organizations might orient action, interact, and plan.Footnote 47 They stress, in the words of Raz, that the rule of law’s value lies in “curtailing arbitrary power, and in securing a well ordered society, subject to accountable, principled government.”Footnote 48 The checklists, however, should not define what the rule of law is. They rather incorporate important means to achieve rule-of-law goals because, as we argue below, they address key sources of arbitrariness.

It is when the conception of the rule of law includes substantive norms and goals, such as a democratic form of government, participation, deliberation, and individual rights, that it becomes more contested. Leading philosophers and social theorists advance thicker conceptions of the rule of law that vary in their inclusion of substantive issues, such as participatory rights and human rights.Footnote 49 As Gianluigi Palombella puts it, the rule of law cannot “coincide with the mere existence of a legal order.”Footnote 50 Theorists such as Ronald Dworkin, Jeremy Waldron, Jürgen Habermas, and Philip Selznick all incorporate a discursive quality of reason-giving and argumentative justification in their conception of the rule of law.Footnote 51 Proponents likewise advance these attributes as important checks on arbitrariness. Indeed, the lack of reason-giving constitutes an important source of arbitrariness, as we explain below.

Going further, Palombella insists that the rule of law requires democracy “paired with fundamental rights.”Footnote 52 Terry Nardin similarly argues that the rule of law should not be confused with the mere existence of laws: “The expression ‘rule of law’ does no intellectual work if any effective system of enacted rules must be counted as law, no matter what its moral qualities.”Footnote 53 These moral qualities, he insists, must include rights: “The expression ‘rule of law’ … should be used only to designate a kind of legal order in which law both constrains decision-making and protects the moral rights of those who come within its jurisdiction.”Footnote 54 United Nations reports on the rule of law similarly incorporate substantive conceptions, including consistency with “international human rights norms and standards.”Footnote 55

More controversially, some World Bank reports have offered definitions of the rule of law that support market-oriented development policies grounded in property rights and contract enforcement.Footnote 56 Secure property and contract rights can be important means to advance the rule of law in that they provide for certainty and predictability and thus protection from power’s arbitrary exercise. However, democratically governed societies will differ in how they define property and contract rights. It is important not to tether the concept of the rule of law to a particular form of political or economic ordering, such as a neoliberal model.Footnote 57

Whether one takes a thinner or thicker view of the means to advance the rule of law, the common goal among these conceptions is to oppose arbitrariness. Although we do not incorporate human rights within the definition of the rule of law, there are clear overlaps – such as regards due process rights – and the two are intertwined and complementary in protecting individuals from power’s unbridled exercise.Footnote 58 Critically, the rule of law is a necessary condition and prerequisite for the protection of human rights, just as it is for democracy. If one can persecute individuals with impunity to stay in power, then formal rights lack bite.

From a socio-legal perspective, the ultimate challenge is implementation in practice (the law-in-action), which will be mediated by social institutions and legal culture. Because law is frequently ambiguous, involving the interplay of standards, rules, and exceptions, the application of the rule of law will always be contested. No legal process is “discretion-free” because law’s meaning is mediated through the operation of institutions and interactions involving people.Footnote 59 The rule of law thus should not be confused with the rule of courts or any other institutional means. It is an end that must be pursued through some form of institutionalization, of which courts can be an important exemplar. But any institutional means can be co-opted, abused, and subverted in practice. It is thus essential to keep the end always in view, and never confuse the existence of a particular institutional apparatus with the rule of law.

To develop appropriate means to protect rule-of-law goals, it is best to start with the source (or sources) of the problem – the different sources of arbitrariness.Footnote 60 Theorists define arbitrary power in slightly different ways, but the term generally refers to power that is subject to no constraints and, in particular, is not made to take account of the interests of those subject to it.Footnote 61 In this vein, Philipp Pettit writes that an arbitrary act is one that “is chosen or not chosen at the agent’s pleasure. And in particular … it is chosen or rejected without reference to the interests, or the opinions, of those affected.”Footnote 62 For a dictionary-oriented, legal definition, the tribunal in the case of Siemens v. Argentina cites Black’s Law Dictionary and defines arbitrariness as follows: “In its ordinary meaning, ‘arbitrary’ means ‘derived from mere opinion,’ ‘capricious,’ ‘unrestrained,’ ‘despotic.’ Black’s Law Dictionary defines this term as ‘fixed or done capriciously or at pleasure; without adequate determining principle,’ ‘depending on the will alone,’ ‘without cause based upon the law.’”Footnote 63

Building from Krygier, we note five sources of arbitrariness to which different rule-of-law prescriptions respond.Footnote 64 A first, primordial concern is where the wielder of power is not subject, in practice, to the law, its controls and limits.Footnote 65 Authoritarian governments, in particular, violate this first and most critical dimension. They may pack institutions with their friends, or institutional decision-makers will decide in their favor out of fear. Democratic governments can as well, as illustrated by the 2024 US Supreme Court decision in Trump v. United States, where the Court granted “absolute” and “presumptive immunity” to the President, respectively for “core constitutional powers” and “official acts.”Footnote 66 When the law does not apply to those who rule, autocrats can attack opponents with impunity. When this dimension is lacking, the rule of law cannot guarantee fair elections and democratic government. The separation of powers and systems of institutional checks and balances are important means to hold rulers to account in support of rule-of-law goals and practices, but they too may be insufficient.Footnote 67

A second source of arbitrariness is where individuals are unable to know and predict how power will be wielded over them. It is because of these risks that many theorists define the rule of law in terms of known, nondiscriminatory, relatively stable, prospective, consistently applied rules. These attributes are important for all areas of law, but they are particularly important for criminal law and the application of sanctions. Individuals then can plan their lives with reasonable certainty and predictability regarding the law, and thus be less subject to coercion. It is this source of arbitrariness that inspired theorists such as Hayek, Fuller, and Raz, as well as the broader Rechtsstaat tradition.Footnote 68 These attributes contribute to greater social trust, facilitating cooperation.

A third source of arbitrariness is where individuals have no place to be heard, inform, question, or respond to how power is exercised over them. Due process assured by impartial institutions is critical for the protection of the rule of law. Raz highlights the importance of institutional machinery, and Waldron the need for contestation, to ensure the rule of law. If citizens have no place to contest decision-making and no institutional mechanism to access justice, the exercise of public power becomes less subject to controls, and decision-makers face fewer incentives to act in a nonarbitrary manner.Footnote 69

A fourth source of arbitrariness, articulated by Habermas and Selznick among others, is where authorities do not engage in public reason-giving in issuing their decisions, which reasons then can be contested, including before judicial, political, and administrative processes. One may, and indeed will, often disagree with the reasons given, but the very practice of public reasoning can provide important constraints on power’s arbitrary exercise. Under the rule of law, in Justice Brandeis’s words, “deliberative forces prevail over the arbitrary.”Footnote 70

A fifth source of arbitrariness is the proportionality of any measure in terms of the reasonable relationship of means and ends.Footnote 71 Decision-makers may create clear rules and provide access to courts but apply sanctions that are clearly disproportionate to the offense. Any restrictive measure should be grounded and justified as regards its proportionate relation to a public goal.

These five sources of arbitrariness all call for institutional checks. Different “thin” and “thick” conceptions of the rule of law respond to these concerns. These conceptions have given rise to numerous rule-of-law “checklists,”Footnote 72 which are important, but only provided that the focus remains on the goal and actual practices. In this chapter, we thus conceptualize legal and institutional attributes advanced by theorists as important means to respond to the above sources of arbitrariness, as opposed to the definition of the rule of law itself.

Because sources of arbitrariness differ, rule-of-law protections can decline or improve along different dimensions in different substantive areas, as documented in the literature on dual states. For example, many authoritarian regimes create rule-of-law protections in commercial and administrative law to attract investment and spur economic growth. In contrast, they do not subject themselves to the law when that would threaten their hold on power. A key test for the rule of law thus lies in the civic and political domains to constrain governments from engaging in repression to maintain power.

In the end, any meaningful understanding of the rule of law must be based on cultures of practice embedded in rule-governed institutions. To quote Nicholas Barber, “the rule of law amounts to a normative demand, a requirement that a certain set of mechanisms for the coercion and regulation of law is desirable.”Footnote 73 Implementing this goal will give rise to variation, in reflection of different traditions, circumstances, and ideologies.Footnote 74 In this vein, Fuller rightly maintained that pursuit of the rule of law is ultimately a “practical art” of developing institutions.Footnote 75 We thus must turn from the question of goals to the question of means. We must address the question of how to – or, as Nicola Lacey writes, “how to develop legal arrangements capable of constraining abuses of power and of addressing such abuses.”Footnote 76 The means entail different forms of checks on power’s uncontrolled exercise.

II The International Rule of Law from a Transnational Perspective

Many are skeptical about transporting the rule-of-law concept to international law. To start, many note the relatively “primitive” nature of international law in international relations, especially given the lack of institutions to enforce compliance.Footnote 77 Simon Chesterman, for example, cites the early rule-of-law theorist Dicey, who suggests international law is “miscalled” law and rather involves “rules of public ethics.”Footnote 78 International relations realists continue in this vein, arguing that international law is epiphenomenal and reflects the interests of powerful states. From this vantage, international law still can be useful for purposes of interstate coordination and cooperation, but powerful states will ignore it when it does not advance their interests.Footnote 79

The political scientist Ian Hurd maintains that one can still conceptualize the international rule of law from an international relations perspective, but one must do so distinctly in terms of the role of “law talk.” For Hurd, international law involves a practice of argumentation in which actors use international law strategically to justify state behavior, which he calls “lawfare.”Footnote 80 Powerful states “have the greatest influence over the design of international rules and the greatest capacity to both deploy and evade them.”Footnote 81 They seek to justify their conduct by offering self-serving interpretations of international law, and those interpretations shape “future readings of the law.”Footnote 82 For these reasons, third world approaches to international law (TWAIL) point to the biases in international law structures and practices that advantage powerful states and powerful constituencies within them.Footnote 83 They nonetheless stress the need and potential for international law.Footnote 84

We see no reason to create a distinct conception of the “international rule of law.” Rather, we maintain that the concept of the rule of law ultimately addresses the relation of authorities to individuals,Footnote 85 but that international law’s horizontal dimension of governing interstate relations is critical directly and indirectly for protecting individuals from power’s arbitrary exercise. We thus retain our conception of the rule of law in terms of goals – to protect individuals from arbitrary power through legal rules and institutionalized practices, while providing channels for cooperative and coordinative activities. We nonetheless contend that international law is critical for advancing the rule of law in multiple direct and indirect ways that affect individuals and societies. At a minimum, the recognition of state boundaries and prohibition of the use of force except in self-defense helps ensure international peace and reduce the violence of war, thus protecting individuals and communities from power’s arbitrary exercise in war. Going further, states can be viewed as agents or trustees in advancing rule-of-law goals, and not simply as subjects and beneficiaries of international law. International law creates norms, institutions, and mechanisms that aim to protect individuals from arbitrary power, whether directly or indirectly. At the same time, international institutions, multinational companies, and foreign states can wield power arbitrarily in ways that affect individuals. International law is thus critical for tempering their unbridled exercise of power as well.

Our assessment of the role of international law and institutions in advancing rule-of-law goals and practices is a transnational one. It incorporates international law and institutions within dynamic processes that implicate rule-of-law concerns within and across states, affecting individuals and societies. From a transnational perspective, we contend that international norms and institutions are important for protecting individuals from the arbitrary exercise of power. However, they also can advance the rule of the powerful by and through law. They thus also must be subject to critical scrutiny and transnational checks.

We build a socio-legal theory of the relation of international law and institutions to the rule of law conceptually and apply it empirically. As we will see in Part III, in an interconnected world trends regarding rule-of-law protections are transnational in scope. They involve shifting norms, institutions, and practices at the local, national, and international levels. These developments are often enmeshed; they interact and recursively implicate international law and institutions, and, in turn, are implicated by them. Following World War II, and, more saliently, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s, international law shifted from “classical Charter-based international law with its emphasis on state-oriented principles and underdeveloped human rights obligations towards a more value-based order which is actually capable of protecting and serving individuals,” including from the arbitrary exercise of power.Footnote 86 Rule-of-law norms and institutions became more salient around the globe, both in discourse and in actual practices.Footnote 87 The empirical question arises as to whether these trends are now in reverse, such that there are cycles in which rule-of-law norms advance and retreat at both the national and international levels.

To assess these trends, one should place international and national law and institutions within a single analytic frame in dynamic relationship with each other. Halliday and Shaffer conceptualize these processes in terms of “transnational legal ordering” that can give rise to the settlement and unsettlement of legal norms as part of “transnational legal orders” (TLOs) in different substantive domains.Footnote 88 TLOs are normative orders that implicate law and legal practice across and within multiple national boundaries. They consist of working equilibria of relatively settled legal norms and practices that can vary in their substantive and geographic reach. Halliday and Shaffer define them as “a collection of formalized legal norms and associated organizations and actors that authoritatively order the understanding and practice of law across national jurisdictions.”

Transnational legal ordering arises out of the transnational framing and understanding of a social problem, which catalyzes actors to seek a resolution through law. Such problems affect all areas of social life and range from global warming to a lack of capital for economic development to the exercise of arbitrary state power. TLO theory thus concords with viewing the rule of law as a solution concept – as a response to a problem, the problem of the arbitrary exercise of power.

Transnational legal ordering entails dynamic processes that lead to the settlement and unsettlement of legal norms. Various facilitating circumstances and precipitating events catalyze lawmaking and changing practices at different levels of social organization, which, in turn, interact in a recursive manner over time. Different factors drive these processes at the transnational, national, and local levels. These factors include diagnostic struggles over the nature of the problem, actor mismatch between the codifiers and implementers of legal norms, indeterminacies in the law, and ideological tensions and contradictions within the norms.Footnote 89 Where certain mechanisms are ineffective, actors may develop new tools. Where new tools are operationalized, actors may seek new ways to harness or thwart them. Through these processes, transnational legal orders can become more or less settled and institutionalized, varying in their geographic and substantive scope, including but not limited to regions. These legal orders also can vary in their alignment with an underlying problem, whether addressing it directly or only tangentially, or addressing all or only a part of it.Footnote 90 For example, the legal order could address a broad definition of the problem (climate change) or narrower ones (such as the regulation of air transport, cargo ships, or energy infrastructure). Legal orders also may overlap and be in competition, as illustrated by advocates contesting the primacy of intellectual property and public health legal orders regarding access to medicines, or of anti-terrorism and national security law in light of due process requirements. Over time, transnational legal orders may rise, transform, and fall as legal norms settle and unsettle transnationally.

Our use of TLO theory in this book departs slightly from the way we have deployed it in the past. In the past, Halliday, Shaffer, and their collaborators viewed legal concepts in terms of how actors at different levels of social organization – ranging from the international to the national and local – framed problems and gave legal concepts meaning through recursive processes. In this way, they examined how legal norms develop, settle, unsettle, and change transnationally, such that their substantive meaning may alter, obscure, or become taken for granted. For example, Shaffer earlier conceptualized “transnational law” from a socio-legal perspective in terms of the “transnational construction and flow of legal norms,” “in which transnational actors, be they transnational institutions or transnational networks of public or private actors, play a role in constructing and diffusing legal norms, even if the legal norm is taken in large part from a national legal model.”Footnote 91

Had we taken this approach, we would study how the meaning of the “rule of law” changes over time transnationally, settling and unsettling in practice in ways that transcend national boundaries. Such an approach would have applied a “phenomenological” conception of the rule of law, as developed elsewhere by Jens MeierhenrichFootnote 92 and applied by Jothie Rajah, who examined different transnational rule-of-law scripts developed by the World Bank, United Nations, and World Justice Project.Footnote 93 In this introductory chapter, in contrast, we define the rule of law as a principle and practice (constraints on the arbitrary exercise of power by setting boundaries on, and channeling, power’s exercise), and we then assess the extent to which the principle and practice are under serious challenge today. This principle (or meta-principle) implicates law’s practice across substantive domains. We still assess changes in legal practice transnationally, but here we do so in light of a principle that we define in terms of goals and practices in response to different sources of arbitrariness. Both approaches (phenomenological and normative) are important for empirical investigation, critique, and policy responsiveness to different social and political contexts.

In this Part II, we assess the direct and indirect relation of international law and institutions to rule-of law goals and practices as we have defined them. We contend that, in an interconnected world, the rule of law should be viewed as a normative social order that involves the horizontal, vertical, and transversal interaction of domestic and international law, which, in turn, reciprocally affect each other.Footnote 94 Any equilibrium at the international, national, or local level will be subject to influence by norms that are conveyed, settle, and unsettle transnationally.

International law and institutions implicate rule-of-law protections for individuals in the following three ways. First, from a minimalist perspective, international law and institutions can help to secure international peace, which ultimately affects individuals and societies. Second, international law and institutions can indirectly affect domestic rule-of-law practices in relation to individuals. National law often incorporates international law; national courts and other bodies may reference it; and national actors may otherwise harness it, including to protect rule-of-law concerns. Third, international law and institutions can directly grant rights to individuals and impose duties on national governments, international institutions, and private actors.

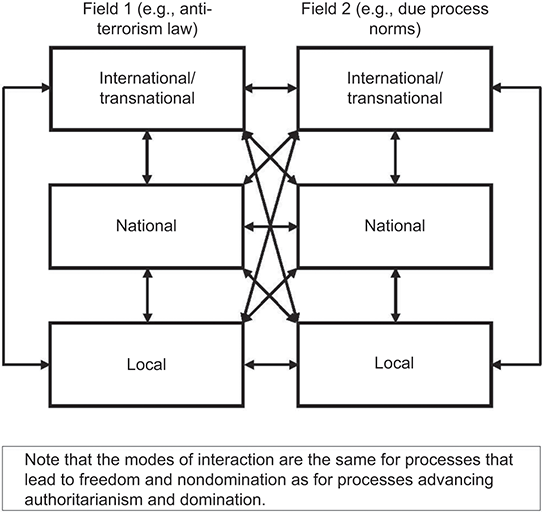

In each case, we note how international law can either support rule-of-law practices or undermine them. As law generally, it can validate practices of freedom or of domination, which is why it is important to differentiate the concept of rule of law from that of rule by law. Because international law is part of larger, transnational, norm-making processes, one should assess interactions between international, national, and local norms, institutions, and practices that implicate the rule of law. Figure 1.1 captures these processes of interaction as regards anti-terrorism and due process norms at different levels of social organization, which we further address below.

Figure 1.1 The transnational web of rule-of-law interactions.

1 Minimalist Perspective of Rule of Law for Nonviolence, Peace, and Public Order

The rule of law links analytically with the concept of peace by stressing the use of law to resolve conflicts in lieu of unbridled coercion and violence. At the international level of interstate relations, one of the core features of a “liberal international order” is the creation of multilateral institutions for the resolution of disputes under international law, thereby enhancing the security of states and their constituents.Footnote 95 There is no greater risk of arbitrary power exercised over individuals than the violence of war. As the philosopher Bernard Williams writes, the “Hobbesian question” of securing “order, protection, safety, trust, and the conditions of cooperation” is the “first” political question: “[S]olving it is the condition of solving, indeed posing, any others.”Footnote 96 It is for this reason that Steven Ratner prioritizes international law’s potential in providing a “pillar of peace” as a core aspect of theorizing international law in terms of justice.Footnote 97 The same is true as regards the rule of law. In a “thin” sense, international law is foundational to political order. It supports the maintenance of secure political communities and thus enhances the prospects of rule-of-law protections for these communities’ members.Footnote 98 Simply put, war and the immediate threat of war subject individuals and communities to increased risks of coercion and violence, whether by a foreign state, their own state, or nonstate actors. Practically, international law can protect, and has protected, individuals and communities from power’s arbitrary exercise.Footnote 99

Relatedly, from a transnational perspective, democratic peace theory provides powerful evidence that democracies grounded in the rule of law are less likely to go to war against each other than are authoritarian states, the latter being more likely to go to war against both each other and democratic states.Footnote 100 Where democratic norms grounded in the rule of law diffuse transnationally, the prospect of peace should increase, giving rise to “security communities.”Footnote 101 These communities may be tied together through shared norms and broader legal orders that become institutionalized, particularly at the regional level.Footnote 102 These two perspectives – democratic peace theory and transnational diffusion of norms – can be combined to show how rule-of-law norms at the national and international levels mutually and recursively support each other to enhance the prospects of peace and nonviolence, and thus reduce the likelihood of arbitrary power inflicted on individuals.

The international institutions created in the decades after World War II, at a minimum, provided rules for governing interstate relations and reducing the risk of armed conflict. One of the goals of promoters of the United Nations and its family of specialized international organizations was to ensure peace among states. The UN Charter prohibits the use of force – and thus war – to settle international disputes other than for self-defense against an armed attack (Article 51) or when authorized by the UN Security Council (Article 42). Regional regimes developed in parallel, with the aim of not only preserving peace within the region but also promoting nonviolent, law-governed, democratic transitions within states. After the end of the Cold War, international institutions grew in prominence. The UN Security Council has never lived up to its purpose under the UN Charter of ensuring “the maintenance of international peace and security.” Following the end of the Cold War, it reached consensus in a few prominent cases, giving rise to interventions, including to promote peace and security in post-conflict settings. Most notably, the Security Council authorized interventions in Iraq in 1991 following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait (Resolution 688), in Bosnia in 1992 (Resolution 770), in Somalia in 1992 (Resolution 794), in Haiti in 1994 (Resolution 940), and in Afghanistan in 2001 (Resolution 1386). Regional organizations in Africa – ECOWAS and the African Union – even acquired the authority to intervene militarily in their member states to uphold law-governed, democratic transitions.

Among the core aims of international courts and other institutions is the peaceful resolution of disputes. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) offers a general-purpose mechanism for resolving disputes when states grant it jurisdiction. Counterfactually, without the ICJ and other international tribunals, it would be more difficult for states to peacefully resolve disputes.Footnote 103 Take, for example, international boundary disputes. The ICJ has been particularly effective in peacefully resolving disputes in this area, complemented by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS). From 1951 to 2021, there were 53 boundary disputes decided by international tribunals, comprising 22 land boundary disputes, 19 maritime boundary disputes, and 12 disputes involving land and sea questions. As shown in Table 1.1, the ICJ decided 37, the PCA 13, and ITLOS 3 in total.Footnote 104 Overall, states complied either fully or partially with 45 (around 85 percent) of these judgments.

Table 1.1 Compliance with international court decisions on land and sea borders

| Compliance | Partial compliance | Noncompliance | Total cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICJ | 26 | 7 | 4 | 37 |

| PCA | 7 | 0 | 4 | 13 |

| ITLOS | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 38 | 7 | 8 | 53 |

The ICJ is complemented by other general purpose and specialized international tribunals. For example, the World Trade Organization (WTO) provides a legalized system for resolving trade disputes. Without it, trade wars are much more difficult to restrain, since tit-for-tat retaliation can lead to greater distrust and conflict, as evidenced both by the tariff and currency wars of the 1930s and the US–China trade war launched by the Trump administration in 2018 as the United States blocked appointments to the WTO’s Appellate Body. Indeed, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull believed that “economic blocs of the 1930s, practiced by Germany and Japan but also Britain, were the root cause of the instability of the period and the onset of the war.”Footnote 105 Among the aims of international investment arbitration is to resolve disputes over the treatment of aliens and their property that earlier had led to armed interventions. Although the investment law regime is subject to significant critique from a rule-of-law perspective, the illegality of the use of force to protect citizens’ property claims abroad represents, at a minimum, a significant advance.

Other international and regional fora provide jurisdiction for a range of disputes within their competence. The European Union (EU) provides a regional model. In this case, the EU and its predecessor organizations, starting with the European Coal and Steel Community, tied a powerful state (Germany) to a regional economic integration project with the aim of ensuring peace within Europe. Alec Stone Sweet analogously conceptualizes the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) under the Council of Europe as a Kantian “cosmopolitan legal order” advancing “Kant’s blueprint for achieving Perpetual Peace.”Footnote 106 These international institutions provide settings in which states can air their differences and resolve them through law and third-party institutions.

Global threats other than war affect the security of borders. Most saliently, there are the increasing risks posed by climate change, which have led to severe droughts and storms, cataclysmic fires and flooding. These threats can spur new interstate conflicts, whether over access to scarce water from shared lakes and river systems or because internal upheaval spills over borders, increasing the risks of power’s arbitrary exercise. International cooperation is required to address the underlying causes of climate change, since one state’s efforts go to naught if greenhouse gas-intensive production shifts elsewhere and other states take no action. International law and institutions can facilitate such cooperation, such as through binding rules, reciprocal pledges, and the generation of funding to address climate change risks. As with international law aimed at reducing the risks of war, international law and institutions addressing climate change also can indirectly support rule-of-law goals by reducing the underlying risks of power’s arbitrary exercise.

Yet, international law and institutions also can support invasions and facilitate domination by powerful states over others. The 1884–85 Berlin Conference carved up Africa, which authorized King Leopold’s brutal exploitation of the Congo. The League of Nations’ and United Nations’ mandate and trusteeship systems served to legitimate Western nations’ continued rule over their colonies, with the UN Trusteeship Council continuing to operate until 1994 when the last trusteeship territory, the island of Palau, became independent from the United States. Powerful states remain dominant in shaping and enforcing international law today, as reflected in the veto powers of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council. The fact that these nations can block the application of any measure as applied to themselves when they violate the UN Charter and invade other countries undermines the rule of law – the first source of arbitrariness discussed earlier. Moreover, when the Security Council authorizes action, there is no international court or other institution to hold it, or countries acting under its authorization, accountable. For example, US and NATO excesses in enforcing a Security Council resolution for a “no-fly zone” in Libya in 2011 led to the overthrow of the Qaddafi regime, and increased insecurity, suffering, and mass violence in that country.Footnote 107 In theory, interventions authorized by international institutions or referencing international law can reduce violence and conflict, but they also can worsen situations, rendering individuals more vulnerable to violence and arbitrary power.Footnote 108 Rule-of-law norms thus must apply to international institutions themselves.Footnote 109

Powerful actors also reference international law to authorize invasions that can lead to increased violence. For example, human rights claims helped frame the creation of a “responsibility to protect” doctrine, which can serve to justify “humanitarian interventions” and thus armed conflict in the name of human rights enforcement.Footnote 110 President Putin’s rhetoric to legitimize Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine in the name of “humanitarian intervention” illustrates how powerful actors deploy humanitarian rhetoric and international law for self-interested reasons. Russia’s veto of a Security Council resolution calling on it to halt its attacks and withdraw from Ukraine illustrates how the Council’s permanent members block the application of international law against themselves.

2 Indirect Processual Links Supporting Rule-of-Law Practices within States

International institutions and international law are important for norm-making, oversight, assessment, and funding of rule-of-law initiatives that indirectly affect institutional practices within states.Footnote 111 They are best viewed as part of larger transnational normative processes involving the conveyance of norms, which ultimately are applied within states toward individuals. Since World War II, international institutions have aimed to delimit state prerogatives affecting the rights of all persons, for which the rule of law is fundamental. They create focal points for transnational networks of civil society groups that can help to embolden and empower those advancing rule-of-law goals domestically. Domestic groups can use reporting, peer review, and judicial or other transnational mechanisms to enhance their positions in domestic political, judicial, and administrative institutions and processes, potentially “locking in” domestic rule-of-law reforms.Footnote 112

One way that scholars have framed the so-called liberal international order in the post-World War II era is to view states as agents of higher-order international rules for the protection of human rights, for which the rule of law provides a foundation. Political scientists Tanja Börzel and Michael Zürn labeled this a “postnational liberal international order” in that it comprised conditionally sovereign states, which gained legitimacy by enforcing and guaranteeing liberal rights, rules, and decisions implicating the rule of law.Footnote 113 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights sets out fundamental individual rights that states are obligated to respect through “the rule of law.”Footnote 114 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Cultural and Social Rights, together with other global and regional treaties, elaborate these rights and create international mechanisms to oversee their application. Over time, these treaties’ membership, scope of coverage, and enforcement mechanisms have expanded.

We conceptualize the protection of human rights, as noted in Part I, as important means that complement and overlap with the rule of law in advancing rule-of-law goals. These rights are almost universally recognized in national constitutions,Footnote 115 which, in turn, reflect transnational processes of constitution-making and constitutional practice.Footnote 116 To be a modern state is to have a constitution, and increasingly since 1945 national constitutions define individual rights and obligate the state to respect and protect them through institutionalized means founded on the rule of law.Footnote 117 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights has been particularly influential in shaping rights provisions in national constitutions.Footnote 118 Such rights are developed recursively in international and domestic law and institutions through transnational processes.Footnote 119 In the words of the late ICJ judge James Crawford, one of the main roles “of international law is to reinforce, and on occasions to institute, the rule of law internally.”Footnote 120 In this vein, in 2004 UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan stressed:

States are now widely understood to be instruments at the service of their peoples, and not vice versa. At the same time individual sovereignty – by which I mean the fundamental freedom of each individual, enshrined in the charter of the UN and subsequent international treaties – has been enhanced by a renewed and spreading consciousness of individual rights. When we read the charter today, we are more than ever conscious that its aim is to protect individual human beings, not to protect those who abuse them.Footnote 121

These protections are contingent on the rule of law.

The protection of individual rights against the arbitrary exercise of power is part of the mission of a range of international and regional institutions. Eight of the principal international human rights treaties include provisions that allow the relevant treaty bodies to receive individual communications alleging violations. The Human Rights Committee, for example, established under the ICCPR, can receive and decide on individual claims of ICCPR rights violations by the 106 states that have accepted the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR.Footnote 122 The Human Rights Committee lacks power to enforce these rights directly, but states are obliged to respond to its findings. In 2022, for example, it found that Australia had arbitrarily interfered with the rights of indigenous Torres Strait Islanders by failing to protect them adequately from the effects of climate change.Footnote 123

This is just one part of the architecture of international human rights institutions, which include the UN Human Rights Council, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights under the UN Secretary-General, the committees created to oversee the other international human rights treaties, and various reporting and investigative bodies, such as the system of UN special rapporteurs. States are accountable to these bodies, and constituents within states can reference and appeal to their work to advance rule-of-law goals. For example, under the UN Paris Principles, over one hundred countries created national human rights institutions, which generated a transgovernmental system of monitoring that facilitates norm diffusion.Footnote 124 Similarly, more reporting mechanisms can have catalytic impacts within countries through media coverage, nongovernmental advocacy, legislative references, and administrative follow-up.Footnote 125

Regional bodies are particularly important for overseeing and monitoring human rights protections implicating rule-of law goals.Footnote 126 The European Union established conditions for membership under which state institutions must guarantee democracy, the rule of law, and human rights (the “Copenhagen criteria” of 1993). It also established a mechanism for holding states accountable for violations of rights contained in the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights (CFR). National judges can hear individual complaints regarding violations of the Charter, and, where there is uncertainty, they can seek interpretive guidance from the Court of Justice of the European Union.Footnote 127 The Court of Justice has found that Article 2 of the Treaty of the European Union “contains values [including the rule of law] which … are an integral part of the very identity of the European Union as a common legal order, values which are given concrete expression in principles containing legally binding obligations for the Member States.”Footnote 128 It has applied the value of the “rule of law” embedded in Article 2 to require member states to maintain an independent judiciary, which is a major concern in Hungary and Poland.Footnote 129 In parallel, the European Commission for Democracy and Law (the “Venice Commission”), within the Council of Europe, is charged with helping states that wish “to bring their legal and institutional structures into line with European standards and international experience in the fields of democracy, human rights and the rule of law.”Footnote 130 These regional bodies can contribute to the formation of regional legal orders, although these too will show internal variation in terms of the concordance of regional, national, and local practice.Footnote 131 Variation among regional legal orders can reflect different regional traditions and transnational borrowings among neighboring countries.Footnote 132

International human rights law and institutions arguably are most powerful when national institutions, such as national courts, reference and enforce international norms within national systems.Footnote 133 This transnational framing of international law resonates with Kim Lane Scheppele’s assessment of international courts in “three-dimensional space.” As she maintains, international courts should not be viewed hierarchically as super appeals courts or primarily as “back stops” to national courts, but rather as part of broader normative orders that horizontally among themselves and vertically in relation to national courts affect institutional practices, particularly for the protection of the rule of law.Footnote 134 All members of the Council of Europe must incorporate the European Convention on Human Rights into national law, and national judges in these countries reference the Convention in applying national law.Footnote 135 The UK Human Rights Act, for example, requires that UK judges interpret statutes, so far as possible, in ways that are compatible with the UK’s international human rights commitments.Footnote 136 In Germany, courts generally are obliged “to take note of and consider the relevant case law of the international courts with jurisdiction for Germany.”Footnote 137

Direct decisions of a human rights court against one state can have effects in other states, illustrating transnational processes at work. Laurence Helfer and Eric Voeten, for example, provide evidence that ECtHR decisions against one country substantially increase the probability of national-level policy change across Europe, such as in the area of the protection of LGBT equality.Footnote 138 Relatedly, within many Latin American countries one cannot meaningfully study constitutional law developments without incorporating their relation to the inter-American human rights system and changes in legal culture regarding the rule of law.Footnote 139 These bodies generate interpretations that courts outside of their regions reference, including other regional courts and other national courts (such as in the United States and India).Footnote 140

Courts also frequently apply or otherwise consider international law in interpreting national law.Footnote 141 In doing so, they participate in, and are critical to, international law’s implementation, development, and practice. As the Supreme Court of Canada stated in the case Nevsun Resources Ltd. v. Araya et al., “Canadian courts, like all courts, play an important role in the ongoing development of international law.”Footnote 142 They are important not only in “implementing” international law, but also in “advancing” it. In that way, they “contribute … to the ‘choir’ of domestic court judgments around the world shaping the ‘substance of international law.’”Footnote 143 The opinion affirmatively cites former member of the Canadian Supreme Court Gérard La Forest, who writes, “our courts – and many other national courts – are truly becoming international courts in many areas involving the rule of law.”Footnote 144

Many international organizations have incorporated and promoted rule-of-law norms in their rules and jurisprudence. For example, WTO panels have found that a central goal of the WTO legal system is to provide individual traders with certainty and predictability from the arbitrary action of other governments. In the United States – Section 301 case, the European Union challenged US unilateral legislation used to threaten US sanctions against it before the WTO dispute settlement system had completed its review. The panel found that such legislation could be challenged “as such” given its “‘chilling effects’ on the economic activities of individuals.” The panel stressed, “it would be entirely wrong to consider that the position of individuals is of no relevance to the GATT/WTO legal matrix … . The multilateral trading system is, per force, composed not only of States but also, indeed mostly, of individual economic operators. The lack of security and predictability affects mostly these individual operators.”Footnote 145

Relatedly, in the United States – Shrimp case, a group of south and southeast Asian nations challenged a US ban on shrimp imports from countries that did not require certain shrimp trawling practices to protect endangered sea turtles. The Appellate Body found that, although the US objective was legitimate, the United States had failed to provide “due process” rights to the other countries to defend themselves and adapt to the new measure. It found that the application of the US measure was “arbitrary” in that the certification process was not “transparent” or “predictable,” did not provide any “formal opportunity for an applicant country to be heard or to respond to any arguments that may be made against it,” did not result in a “formal written, reasoned decision,” and offered “no procedure for review of, or appeal from, a denial of an application.”Footnote 146 The Appellate Body focused, in particular, on the transparency obligations set forth in Article X of the GATT, pursuant to which WTO members are to publicize their laws and regulations so as to give foreign traders proper notice.Footnote 147 These requirements respond to two of the sources of arbitrariness we foregrounded in Part I – the provision of transparent, published rules, and of an impartial tribunal where persons can respond to and challenge an authority’s decisions against them.

The United Nations, World Bank, and other organizations, including regional and national agencies, have created a rule-of-law industry of consultants giving technical advice, which intensified in the 1990s and 2000s.Footnote 148 Discourse on the rule of law proliferated in Security Council resolutions, in Secretary-General reports, and in other UN groups, particularly as relates to UN peacebuilding and rule-of-law assistance in post-conflict settings.Footnote 149 Some of these processes focused on legal empowerment to support civil society and grassroots organizations within states.Footnote 150 As one UN document declares, the rule of law is a concept “at the very heart of the UN mission,” which is “interlinked and mutually reinforcing” with human rights and democracy.Footnote 151 In parallel, rule-of-law promotion became central within the World Bank and other development agencies.Footnote 152

International and transnational processes are also critical for targeting the practices of nonstate entities, such as multinational corporations that operate in countries with few rule-of-law protections. The United Nations developed Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in 2011, to which multinational corporations agree to adhere.Footnote 153 Private organizations and national regulatory agencies have promoted reporting on adherence to legal norms involving expanded environmental, social, and governance practices (ESG), as under the Global Reporting InitiativeFootnote 154 and the Equator Principles.Footnote 155 At times, different public and private initiatives combine in complex ways to bolster rule-of-law protections, such as in the industrial workplaces of global supply chains.Footnote 156

However, just as international law and institutions can support rule-of-law processes, they also can undermine them. The turn to securitization after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks offers a powerful example. The UN Security Council created an Al-Qaida and Taliban sanctions regime in which a sanctions committee, mirroring the composition of the Security Council, could require the global freezing of an individual’s assets with no transparency or due process. Following the Security Council’s lead, countries around the world passed anti-terrorism laws that governments then used in repressive ways.Footnote 157 Some human rights and other regional courts responded to these developments, most notably in the European Union in the Kadi case. There, the European Court of Justice voided an EU regulation implementing UN Security Council mandates to freeze the assets of suspected terrorists and their financiers on the grounds that it violated the accused’s due process rights.Footnote 158 Other courts followed suit.Footnote 159 This response catalyzed some Security Council reforms, notably the creation of an Office of the Ombudsperson, although its powers were limited.Footnote 160

Private actors, such as multinational companies, also harness rule-of-law rhetoric to advance their material interests. Public and private actors have developed different indicators to measure the rule of law, some of which reflect a neoliberal tilt that can favor foreign capital.Footnote 161 The Heritage Foundation’s rule-of-law index, for example, focuses on the security of property rights.Footnote 162 Bilateral investment treaties and investor–state arbitration highlight how businesses may use international law to challenge government regulations that, investors contend, undermine certainty and predictability under the rule of law. The Tecmed arbitration, for example, recalling Hayek’s attack on social welfare legislation, set a standard for “fair and equitable treatment” under which “the foreign investor expects the host State to act in a consistent manner, free from ambiguity and totally transparently in its relations with the foreign investor so that it may know beforehand any and all rules and regulations that will govern its investments.”Footnote 163 Because democratic political processes legitimately change environmental, labor, and other regulations over time, the Tecmed standard of fixing all rules and regulations in advance could be highly constraining. Business can use it not only to sue states for billions of dollars when new regulations violate business “expectations.”Footnote 164 They also can chill regulation by threatening legal claims.Footnote 165 Yet, domestic institutions often operate corruptly and arbitrarily, which is a central reason to create international institutional complements. It is thus critical to retain focus not only on rule-of-law goals but also on institutional alternatives to pursue them, all of which will be imperfect, but where some will be better or worse in different contexts.Footnote 166

3 Direct Links between International Institutions and Individuals

International law also, in some cases, provides direct legal protections and legal accountability for individuals in support of the rule of law. It can do so in jurisdictions where international law is directly applicable as a cause of action before national courts, and under treaties granting individuals the right to bring direct claims against states before regional courts. The most active regional human rights court is the ECtHR, followed by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR), and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights. These regional human rights courts receive and adjudicate individual claims of state violations of the relevant regional treaties.

In these cases, international law and institutions serve, in part, as a backstop to protect the rule of law, while also potentially shaping the normative field transnationally. International human rights courts, like the ECtHR and the IACtHR, can accept jurisdiction over a petition only after all domestic legal recourse has been sought and exhausted. In those cases, where domestic courts are to enforce rights under the convention but fail to do so, individuals retain the right to bring claims directly to the regional court in question. Stone Sweet labels such tribunals “trustee courts,” since they are charged not with advancing state purposes but rather with holding states accountable for violations of treaty-based rights against those within the state’s jurisdiction.Footnote 167 As regards criminal law, international criminal law and courts primarily serve to establish responsibility for international crimes when domestic institutions are incapable of, or prevented from, doing so. The International Criminal Court (ICC) was designed to provide for legal accountability when state institutions fail. The ICC Office of the Prosecutor prosecutes genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression only when states are unwilling or unable to do so. In practice, it has catalyzed national investigations and some prosecutions for atrocity claims, and it can have other indirect effects.Footnote 168 Likewise, in investment law, under the World Bank’s Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes, a “Contracting State may require the exhaustion of local administrative or judicial remedies as a condition of its consent to arbitration under this Convention,” although this requirement often is not applied in practice.Footnote 169

These complementarity mechanisms prioritize legal decision-making within domestic jurisdictions. They recognize domestic authorities as the primary guardians of the rule of law, but subject to an international accountability mechanism. In the process, they can enhance legal certainty and equal application of the law. By empowering domestic courts to oversee compliance with legal obligations (which directly or indirectly reflect international law), complementarity mechanisms can broaden international law’s reach within states.Footnote 170 There is some (preliminary) empirical evidence that they may do so better than the alternative of using international tribunals as substitutes for domestic courts.Footnote 171

In practice, international institutions are both promoters (on the offensive) and subjects (on the defensive) of the rule of law. Although there is no centralized public power at the international level, international and regional institutions began to exercise increasing authority directly over individuals following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, particularly in relation to peacekeeping operations, sanctions, the use of force, and the US-pronounced “war on terror.” Given its new regulatory roles, the United Nations’ adherence to the rule of law has been seriously challenged. While the UN established thirteen peacekeeping operations between 1946 and 1988, with constrained roles that were primarily tasked with monitoring ceasefire lines, the UN Security Council has created fifty-eight additional operations around the globe since 1988, whose operational scope significantly expanded, including the provision of basic policing functions.Footnote 172 The Security Council authorized peacekeeping and rule-of-law-building mandates in Afghanistan, Iraq, Haiti, Sierra Leone, and Timor Leste, as have NATO and the European Union in Kosovo and the African Union in Somalia. When UN personnel were accused of murder, rape, torture, corruption, and other tortious acts, the United Nations claimed immunity, in violation of fundamental rule-of-law accountability norms, spurring protestations against UN practices.Footnote 173 Similarly, while the Security Council applied only two sanctions regimes in its first forty-three years (against the racist, white minority regimes of Rhodesia and South Africa), since 1989 it has imposed thirty-two additional ones.Footnote 174 The Security Council also increasingly authorized the use of force in its resolutions, rising from one extraordinary instance during the Cold War (in Korea when the Soviet Union briefly absented itself from the Security Council) to forty-eight resolutions between 1990 and 2014.Footnote 175

The Security Council has been particularly challenged for exercising legislative and administrative power to combat “terrorism.” After the September 11, 2001, terror attacks, the Security Council issued a series of resolutions, most notably Resolution 1373 which, among other matters, required states to criminalize terrorism in domestic law and freeze assets of individuals and groups that the Security Council blacklists.Footnote 176 Anti-terrorism laws proliferated globally, and government officials used them to advance their own agendas, including to criminalize dissent.Footnote 177 The Security Council ordered the seizure of an accused’s assets with little to no due process, as noted in Section 2. As Scheppele writes, “for states whose commitment to international law is part of their own deep devotion to the rule of law as a basic principle of state legitimacy, new draconian anti-terrorism laws could be portrayed as necessary in order to comply with international law,” regardless of the lack of due process.Footnote 178

From the vantage of TLO theory, national and regional courts can intervene to protect rule-of-law concerns involving international institutions, just as international institutions have done regarding national practices.Footnote 179 They are part of a broader transnational legal process. As we have seen, some regional and national courts responded by constraining compliance with Security Council asset seizure orders where they were deemed to violate rule-of-law requirements within regional and national legal orders, as in the Kadi case.Footnote 180 The Security Council responded in 2009 by creating the Office of the Ombudsperson, empowered to investigate and make “delisting” recommendations. In this transnational sense, the late judge James Crawford was not wholly correct when he wrote that only when the International Court of Justice has “clear jurisdiction judicially to review action of all United Nations political agencies, including the Security Council … could the rule of law be said to extend to international political life.”Footnote 181 Nonetheless, serious challenges remain, illustrated by the ombudsperson’s resignation in 2021 on rule-of-law grounds, including the lack of institutional independence of the Office of the Ombudsperson, the Security Council’s extensive reliance on confidential evidence, and a refusal to permit petitioners to examine the reasons for their inclusion on the sanctions list.Footnote 182 These ongoing challenges continue to catalyze responses and reform proposals from within and outside the Security Council by state and nonstate actors.Footnote 183