I Introduction

This chapter speaks to the conjunction of two questions that reach to master trends of our time.Footnote 1 On the one hand, the UN Security Council (UNSC) stands at the apex of the international political order, the most symbolically powerful political entity in the world beyond the state. The UN Charter empowers the UNSC to make new law, as its decisions are legally binding on all UN member states. Yet the Charter does not set out any clear mechanisms to temper the Council’s power. What, then, are the limits on that power? On the other hand, the UNSC has emphasized both the importance of the rule of law (ROL) in international affairs, as well as its own central role in promoting ROL. As ROL is arguably at the forefront of global discursive frames for ordering power in the contemporary world, how might its discursive power be translated into effective means of constraining the UNSC?

Both of these questions may be approached productively through the theoretical lens and empirical scholarship on the theory of transnational legal orders (TLOs). We ask, What do struggles over tempering UNSC power through ROL norms and practice reveal about the properties of transnational legal orders (TLOs)? And, conversely, what can TLO theory illuminate in the natural history of the UN’s embrace of ROL as ideology and practice? From the vantagepoint of TLO theory and research, the ROL beyond the state and the ROL within the UNSC exemplify two distinctives that are associated with a class of TLOs that pose particular challenges for the institutionalization of a legal order that transcends sovereign state boundaries. In contrast to those TLOs where a single global script or law purports to encapsulate a normative consensus, such as the UN Convention on Contracts for the International Carriage of Goods Wholly or Partly by Sea (Rotterdam Rules)Footnote 2 or the soft law principles on anti-money laundering propagated by the Financial Action Task Force,Footnote 3 there is no single codified script for transnational ROL.Footnote 4 And in contrast to TLOs authorized by a single transnational global or regional institution, such as international criminal law, which is codified by the Rome Statute and adjudicated by the International Criminal Court, or European human rights law, which is codified by the European Convention on Human Rights and adjudicated by the European Court of Human Rights, ROL has no single authorizing institution or indeed any single institution responsible for holding states and other actors accountable to ROL.

Here, then, is an empirical curiosity. While there is no single script and no single authorizing institution for a global legal order adhering to ROL norms, the apex institution in the post-WWII political order nonetheless pays rhetorical dues to that rather inchoate body of norms. Yet, in an inherent contradiction, the very body that now discursively champions ROL – the UNSC – has been reluctant to subject itself to either explicit norms or institutional arrangements that would temper its power.Footnote 5 Indeed, Scheppele proposes that ROL has not only been subordinated to expedient great-power interest in the UNSC but may have been appropriated to ends contrary to its loftiest ideals.Footnote 6

The chapter unfolds in five parts. First, we outline our research design and its empirical sources. Second, we sketch an interpretive narrative of UNSC engagement with ROL from the early 1990s to the present in three areas of UNSC action: peacekeeping, sanctions, and use of force. Third, we offer a schematic framework for ROL in the UNSC insofar as it applies to UNSC mandates for these three areas. We propose that ROL in the UNSC manifests itself in three dimensions: discourse, procedure (or rules), and structures. These dimensions come into play both internally, within the UNSC itself, and externally, in ROL institution-building in and between states, as well as in post-conflict zones, with a rather gray area between them (e.g., when the UN peacekeeping missions are themselves subject to ROL oversight for the behavior of their personnel). Fourth, we examine the interplay of a so-called meta-TLO for rule of law with three micro-TLOs under construction within the UNSC itself. We conclude with reflections on the capabilities of empowering elected members of the UNSC and weaker states in the UN to press ROL norms on the UNSC as a springboard for ROL global governance via the UNSC.

II Design

1 An Historical Moment

The Security Council’s engagements with the rule of law can be traced back to its very first meeting, on January 17, 1946, when the French ambassador Vincent Auriol observed: “[W]e are ushering in an epoch of law among peoples and of justice among nations. The UN Security Council’s task is a heavy one, but it will be sustained … by our remembrance of the sufferings of all those who fought and died that the rule of law might prevail.”Footnote 7 Yet, despite this early appearance in the work of the Security Council, the rule of law featured rarely in the Council’s deliberations as the Cold War set in. But it would return with a vengeance following the end of the Cold War, when the concept would become increasingly influential in the UNSC’s deliberations and decisions.Footnote 8

Our research pivots on a key moment early in the first decade of the twenty-first century. On September 24, 2003, the Security Council held the inaugural meeting on its new agenda item entitled “Justice and the Rule of Law.” The first speaker at that meeting, Secretary-General Kofi Annan, observed that: “This Council has a very heavy responsibility to promote justice and the rule of law in its efforts to maintain international peace and security. This applies both internationally and in rebuilding shattered societies.”Footnote 9

Arguably, Secretary-General Kofi Annan’s clarion call for a UN rule-of-law agenda in his speech of September 24, 2003, marked a turning point for the UNSC. It was an occasion in which Farrall was informally, even serendipitously, implicated (see Appendix 2). The UNSC sessions on ROL in 2003 and 2004 brought to a head numbers of issues that had been arising in global peace and security since the end of the Cold War and opened up prospects for new normative orders in which variants of ROL might be institutionalized as TLOs. The initial UNSC meeting on the rule of law paved the way for the Council’s sustained engagement with the concept, beginning with its consideration, the following year, of a definition proposed by the Secretary-General to guide the UN’s work.Footnote 10

We treat the years from 1990 to 2003/2004, and the pivotal moment in the 2003/2004 UNSC sessions on ROL, as a recognition of the dramatic expansion of activity that occurred in the UNSC’s use of its powers to maintain international peace and security following the end of the Cold War and the accompanying decades of paralysis in Security Council decision-making caused by ideological antagonism between key permanent members from both the East and the West.

2 A Hard Case

We acknowledge that it is open to debate whether the ROL does or might serve as a constraint on UNSC activities. The UN’s founders unashamedly established the Council as a political body, pairing the lofty aspirational ideals set out in the UN’s principles and purposes, including the promotion of equality and justice, with the pragmatic concession to five great powers (P5) of permanent membership and an accompanying veto power. This marriage of convenience between principle and pragmatism secured the participation of those most capable of destabilizing the new experiment in international organization by granting each of the five permanent members the capacity to prevent the UNSC from taking action by exercising its veto.

This fact, combined with the Charter’s vagueness surrounding the limits on the UNSC’s exercise of its Chapter VII powers, has led commentators to bemoan both the Council’s capacity to do pretty much whatever it wants when the P5 do not disagree, as well as its incapacity, due to the veto, to ensure that it exercises its powers to maintain international peace and security in a consistent, impartial manner.

The UNSC undeniably represents a ‘hard’ case when it comes to evaluating it as a ROL/TLO case study. Indeed, it struggles to satisfy most of the checks and balances to arbitrariness identified by Shaffer and Sandholtz, such as application of law to rulers; predictability of published rules; available fora for bringing challenges; proportionate link of means to end so that they have some factual grounding; and reason-giving.Footnote 11 Yet the fact that the UNSC’s decisions are binding upon all UN member states under Article 25 of the Charter reinforces the direct relevance of the ROL to its work: the UNSC relies on member states to implement its decisions in good faith in order to be an effective ROL-creator. This raises the stakes when it comes to the UNSC’s performance as a ROL-adherent.

3 A Restricted Focus

Our research design can be positioned with regard to important scholarly interpretations and interventions on UNSC activities vis-à-vis the ROL and with respect to our own empirical data and methods.

With respect to scholarly framing, there are several studies of the contemporary role and activities of the UNSC in general,Footnote 12 yet before 2010 the effect of the concept of the rule of law on UNSC practice had attracted less scholarly attention. While there was already a substantial literature on the general promotion of the rule of law as part of development and peacebuilding,Footnote 13 less scholarship had analyzed the particular role of the UNSC in promoting the rule of law or the extent to which the UNSC’s activities to maintain international peace and security themselves promote the rule of law. Some legal scholars had explored whether and how the Council’s almost unfettered power to take Chapter VII action might be reconciled with the notion of the rule of law.Footnote 14 Others had examined the UNSC’s relationship with the rule of law in carrying out particular activities, such as imposing sanctionsFootnote 15 or deploying peacekeeping operations.Footnote 16 But prior to Charlesworth and Farrall’s Australian Research Council-funded partnership with the Australian Civil Military Centre on the project Strengthening the Rule of Law through the UN Security Council, there had been a dearth of systematic studies examining the theory and practice of the UNSC’s relationship with the rule of law when employing its most prominent tools to maintain international peace and security: peace operations, sanctions, and the use of force.

An exception is Chesterman’s earlier work on UNSC and the rule of law in cooperation with the Austrian government.Footnote 17 Using examples from various UNSC activities, his research provides a general analysis of the UNSC in different “modes” of decision-making, such as “legislator,” “executive,” and “judge.” He does not, however, study comprehensively or systematically the theory and practice of the UNSC and ROL in any particular one of the UNSC’s mandates, including the now well-defined UNSC spheres of activity in peacekeeping, sanctions, and use of force. Chesterman’s policy proposals, moreover, exude more confidence in the prospect of extrapolating the institutional separation of powers model within states to the global domain.

Most recently, Scheppele and her colleaguesFootnote 18 have offered a powerful critique of the UNSC’s adherence to the ROL in its interventions directed at anti-terrorism. Perversely, argues Scheppele, the UNSC in an “imperial mode” subverts the ROL, not only setting itself above these norms but wilfully acting contrary to the very values it preaches to the world. Dominated by the P5,Footnote 19 and the common cause found by an otherwise divided P3 (US, UK, France) v. P2 (Russia and China), the UNSC permits, even promotes, the expediency of force, sacrificing the inconvenience of ROL norms for an instrumental goal.

Although both these frames warrant careful engagement on their own terms, we take a more defined and constrained approach. Our exclusive focus on peacekeeping, sanctions, and use of force, which share some overlaps with both Chesterman’s and Scheppele’s work, nevertheless bounds us more closely to appraise the breadth and depth of UNSC decision-making and behavior vis-à-vis the ROL. By restricting ourselves to these three areas of UNSC action – peacekeeping, sanctions, and force – we attend to the pointy end of Council activity, as they are perhaps the most well-publicized, ambitious, and controversial measures it employs to fulfil its primary responsibility under the UN Charter for the maintenance of international peace and security.Footnote 20

4 Interior Empirical Data

Our empirical design combines two bodies of data. Like other scholars, we draw heavily on official sources. Unlike most other scholarship, we benefit from the interplay of Farrall’s participant observation internal to the UNSC operations and his involvement in external activism by academics, civil society, the military, and states to reshape ROL practices internal to the UNSC and externally in its operations. Our perspective for this narrative overview ranges across insider and outsider roles, encompassing different periods in which Farrall has undertaken stretches of insider and outsider observance, as well as stints in which he has engaged actively as a participant with the intent to strengthen the UNSC’s capacity both to promote and to respect the rule of law. Farrall interned at a UN-accredited nongovernmental organization (the Quaker United Nations Office, 1996–97) and was later a UN Secretariat staffer working inside the UNSC and its sanctions committees in New York (2001–04), on the UN Secretary-General’s Good Offices Mediation Team in Cyprus (2004, 2008), and for the UN’s then biggest peace operation, the UN Mission in Liberia (2004–06). As a scholar, he worked initially on UN sanctions and international law (1998–2004) and subsequently as an Australian Research Council chief investigator on two multiyear research projects analyzing the UNSC and its relationship to the rule of law (2011–22).Footnote 21

Across these roles, he has sought to influence the UNSC’s relationship with the ROL in at least three ways. First, his book United Nations Sanctions and the Rule of LawFootnote 22 presents in an appendix a series of basic policy recommendations to increase the Council’s capacity to reinforce the rule of law through its sanctions practice.Footnote 23 Second, in March 2016, Hilary Charlesworth and Jeremy Farrall, with accompanying expert commentary by Terence Halliday, presented sixty-six policy proposals for strengthening the ROL through the UNSC to a packed conference room at UN headquarters in New York, following which the document setting out the proposals was published as an official UNSC document.Footnote 24 Third, with his colleagues on the E10 Influence Project, he has developed an analytical framework to evaluate and demonstrate instances in which elected members (the so-called E10) have shaped UNSC outputs, despite the fact that they do not possess a veto power.Footnote 25 Drawing on empirical studies of E10 influence, the project is advancing proposals to enhance the capacity of the E10 to influence UNSC decision-making.Footnote 26

III The UNSC and the ROL after the Cold War

1 UNSC Formal Powers to Promote the Rule of Law: A Double-Edged Sword

The UN Charter grants the Council primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security.Footnote 27 The Charter further equips the Council with a wide range of powers to promote the peaceful settlement of international disputes,Footnote 28 and to take coercive action, including mandating the application of sanctions and authorizing the use of force, to maintain or restore international peace (Chapter VII).Footnote 29 Critically, the Charter also requires all UN member states to give effect to the Council’s decisions (Article 25), thus giving those decisions the force of law.

This ability to take legally binding decisions gives the Council substantial capacity to promote the rule of law in international affairs. Ultimately, the Council’s effectiveness hinges on the capacity and willingness of UN member states to take the necessary steps to convert its decisions into action.Footnote 30 States are more likely to do this if the Council has a reputation for promoting and respecting the rule of law.

2 The UNSC’s Expanding Use of Its Powers since the End of the Cold War

In the UN’s first four-and-a-half decades, the ideological divide between East and West severely restricted the UNSC’s ability to exercise its powers to promote peaceful settlement and maintain international peace and security, with the consequence that the intervention tools we focus on here – namely, peacekeeping, sanctions, and force – were rarely employed. As a consequence of the infrequency of UNSC action in its first four decades, much of the Cold War era scholarly literature on the Council’s powers, including in particular its Chapter VII powers to apply sanctions and authorize the use of force, focused on the question of how to enable the Council to use its powers more regularly.Footnote 31 The notion that the Council might exceed its Chapter VII authority was practically unimaginable to the Cold War academy. However, things changed dramatically after the Cold War, with the Council expanding its activities across all three areas.

The development of peacekeeping is widely considered to be a Cold War success story. Peacekeeping was an innovation borne of necessity in the UN’s early years, when it proved impossible to realize the Charter’s vision of UN member states contributing their own military forces to a standing UN army under UN command.Footnote 32 Instead, the Secretary-General worked initially with the UN General Assembly, then increasingly with the UNSC, to deploy peacekeepers between hostile forces who had agreed to ceasefires. From 1946 until 1988, the UN established thirteen peacekeeping operations (PKOs). These first-generation operations, premised on three core peacekeeping principles of consent, impartiality, and non-use of force (except in self-defense), were generally tasked with the basic responsibility of monitoring ceasefire lines. Following the end of the Cold War, however, the incidence, scope, and ambition of peace operations expanded significantly. Since 1988, the UNSC has created fifty-eight additional PKOs, deployed around the globe, from Haiti to East Timor and from the Balkans to Mozambique. These post-Cold War operations have been tasked with a broad range of responsibilities. In the case of UN transitional administrations in Kosovo and Timor-Leste, this has even included responsibility for practically all the tasks normally carried out by state institutions. Of particular interest for this chapter, twenty-first-century peace operations have routinely been mandated to strengthen the ROL, with a focus on (re)building police forces, corrections facilities, and judicial systems.

In the area of sanctions, between 1946 and 1989 the UNSC was only able to apply two sanctions regimes. In 1966 the Council applied its very first sanctions regime against the illegal white minority government of Ian Smith in Southern Rhodesia.Footnote 33 In 1977 the Council applied its second sanctions regime, comprising an arms embargo, against the apartheid administration in South Africa.Footnote 34 Since the end of the Cold War, however, the Security Council has been able to achieve the necessary agreement to impose sanctions far more frequently. In the twenty-five years since the Cold War, the Council has created thirty-two additional sanctions regimes, bringing the total number of UN sanctions regimes to thirty-four.Footnote 35 The Council has employed its sanctions powers so frequently in the post-Cold War era that the focus of contemporary scholarly literature now tends to be on how to constrain, rather than facilitate, the Council’s use of sanctions.Footnote 36

In the area of force, Blokker has observed that during the Cold War it was “inconceivable” that the UNSC would authorize the use of force.Footnote 37 However, there was one extraordinary instance during the Cold War. It occurred on July 7, 1950, when the Soviet Union made the ill-judged decision to absent itself from a UNSC meeting on the item “Complaint of aggression upon the Republic of Korea,” in protest at the alleged misrepresentation of China on the UNSC. However, with the Soviet Union not present to exercise a veto, the UNSC subsequently proceeded to adopt Resolution 84 (1950), in which it determined that an armed attack upon the Republic of Korea by forces from North Korea constituted a breach of the peace,Footnote 38 then recommended that UN member states assist the Republic of Korea by making military forces available to a unified command under the United States.Footnote 39 As with peacekeeping and sanctions, the UNSC’s authorizations of force have increased substantially since the end of the Cold War. Writing in 2000, Blokker identifies twenty-seven resolutions containing authorizations of force – for purposes including the enforcement of sanctions, liberating a country from foreign occupation, and returning to power ousted legitimate authorities – spanning eleven situations on the Council’s agenda, ranging from Iraq in 1990 to East Timor in 1999.Footnote 40 Bannelier and Christakis trace an additional twenty-one resolutions authorizing the use of force between 2000 and 2014.Footnote 41

3 ROL Challenges in the Areas of Peacekeeping, Sanctions, and Force

The Security Council has taken important steps since 1990 to strengthen the rule of law through its use of peace operations, sanctions, and force. However, considerable ROL challenges remain.

In the area of peacekeeping, while the Council has routinely included the task of strengthening the rule of law in the mandates of its twenty-first-century multidimensional peace operations,Footnote 42 inadequate responses to peacekeeping misconduct scandals during this same period, including in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic, revealed that peace operations and peacekeepers were not always held to the same legal standards as those whose peace they were keeping.

In the area of sanctions, in 2009 the Council made a significant effort to provide greater due process afforded to individuals subject to targeted sanctions under the 1267 (Taliban/Al Qaida) sanctions regime by creating the Office of the Ombudsperson.Footnote 43 In 2011, when the Council split that sanctions regime into two separate regimes – the 1988 (Taliban) and 1989 (Al Qaida) sanctions regimes – it empowered the Office of the Ombudsperson, which would now apply only to the 1989 sanctions regime, to investigate the grounds upon which individuals were included in the targeted sanctions list and, when appropriate, to recommend delisting.Footnote 44 Moreover, the Council clarified that the Ombudsperson’s delisting recommendations must be implemented unless the 1267/1989 sanctions committee as a whole or the Council itself were to decide otherwise.Footnote 45 Nevertheless, despite this significant improvement in the due process accorded to individuals on the 1989 Al Qaida sanctions list, those on the other (dozen or so) active targeted sanctions lists do not have recourse to any Ombudsperson process.

In the area of force, the endorsement of the “responsibility to protect” doctrine by member states in 2005 recognized the responsibility of all states to protect their own civilians threatened by genocide, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, and war crimes.Footnote 46 Where a state was unwilling or unable to meet its responsibility to protect, there was now a responsibility on the international community to intervene to protect those civilians, using force when necessary and acting through the Council. This new doctrine sought to introduce more principled decision-making into the highly politically charged environment surrounding decision-making on the prospective use of force. Yet excesses in the implementation of the Council’s authorization to use force to protect civilians in Libya under Resolution 1973 (2011) raised concerns about the Council’s accountability under the rule of law.Footnote 47

The Council’s capacity to serve as an effective promoter of the rule of law and guardian of international peace and security is shaped by its response to these challenges. There is thus a strong need to continue refining the way in which the Council’s decisions and activities both promote and respect the rule of law.

IV ROL and the UNSC: A Conceptual Frame

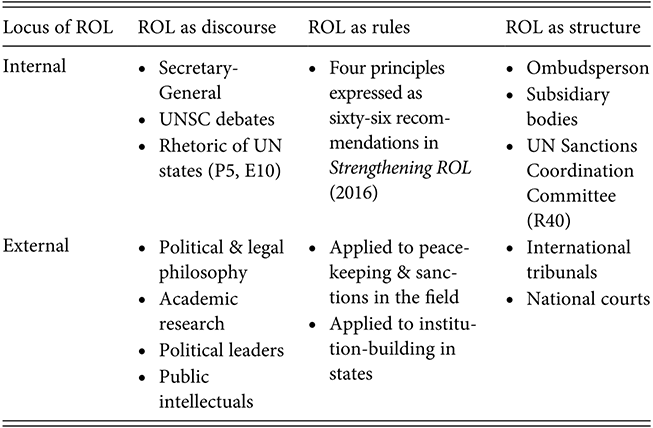

An overview of the UNSC’s encounters with the ROL since the 1990s reveals that ROL manifests itself in three dimensions: discourse, procedures and rules, and structures.Footnote 48 Each of these has an internal focus, within the UNSC itself, and an external focus, in the fields of activity in which the UN mounts its missions.

We designate as internal those aspects of deliberation and decision-making that occur within the UNSC, whether as an actor or an arena. We designate as external those occasions where the UNSC seeks to strengthen ROL because it judges that there has been a breakdown or vacuum of some sort. Thus, peace operations are tasked to strengthen ROL because local ROL authorities and institutions are not able or unwilling to do so. Sanctions are applied against governments and other actors who represent a threat to the peace, which in turn undermines the international ROL. And force is authorized against governments and other actors who represent an even more urgent threat to or breach of international peace and security, and hence to the international ROL.

The relationships between the internal and external locations of the three dimensions align theoretically with Shaffer and Sandholtz’s conceptualization of rule of law as both “principle and practice.”Footnote 49 The ROL is not unidimensional; it encapsulates both frames of meaning (discourses and rules) and structures that institutionalize that meaning.

It is useful to cross-classify these dimensions and review them systematically (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Dimensions of ROL in the UN Security Council

| Locus of ROL | ROL as discourse | ROL as rules | ROL as structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal |

|

|

|

| External |

|

|

|

1 Discourse

We designate as “discourse” the bundle of abstract formulations about the rule of law that are expressed through speeches, policy statements, academic writings, and reflective commentary in the public sphere that is brought to bear on the UN in general and the UNSC in particular. These correspond substantially to the “meta-principle” of rule of law identified by Shaffer and Sandholtz.Footnote 50 Each discursive form has its own distinctive properties, its own internal logic, rhetorical characteristics, epistemological frames, target audiences, arenas of engagement, and platforms for presentation. While these warrant much more refined empirical analyses in their own right, for present purposes we proceed on the basis of a primary distinction between internal and external forums or arenas in which discourse is situated.

The internal rhetoric on ROL is well marked by Secretary-General Kofi Annan’s pivotal speech on September 24, 2003. The speech points to the wider phenomenon of rhetorical expression of ROL in pronouncements, statements, and justifications by actors within the UNSC, within the UN, and in the wider international community of nations. In his analysis of UNSC resolutions in the decade before 2005, Farrall observed that its pronouncements on the rule of law were “increasingly frequent,” yet “fluid” in meaning, “elusive” and “chameleon-like.”Footnote 51 At least five clusters of meaning variously pointed to “law and order” or “holding criminals accountable,” to “principled governance” or “protection and promotion of human rights,” or to “resolving conflicts in accordance with law.”Footnote 52 Sometimes these complemented each other, sometimes one or another appeared, and sometimes it was unclear which of these adequately captured the vague allusions of a resolution. They functioned as rallying calls for adherence to abstract ideals which might serve as an umbrella for normative consensus and as legitimation for UNSC action. As rhetoric, they valorized an inchoate ideal that arguably had an inner core of commitment to minimizing the “misuse or abuse of political power.”Footnote 53 We shall observe, however, that between 2003 and 2020 the discourse within the UNSC became more clearly articulated and sharpened as it was expressed in action items and pragmatic recommendations (see Appendix 1).

External formulations of ROL of course rest upon the vast scholarly literature on ROL in its historical emergence, comparative and contextual expression, and philosophical and theoretical debates.Footnote 54 Our focus, however, adheres more closely to scholarship that holds the UNSC itself to account under ROL norms.Footnote 55 Here, we position ourselves more closely to Chesterman’s ambitious and optimistic agenda for the UNSC to extrapolate from an institutional configuration within states to a global configuration across states, and less closely to Scheppele’s pessimistic indictment of the UNSC as a subverter rather than propagator of ROL beyond the UNSC in its anti-terrorism activities following 9/11. Our focus is particular – on use of force, peacekeeping, and sanctions – and limited on what might be possible in the milieux of power within the UNSC.

It is also disciplined by an interior awareness of how the UNSC functions in day-to-day activities and is conditioned by a realism of what is conceivably possible, given that other realism of great-power politics. Here, we find an affinity with Krygier’s efforts to valorize ROL as a prevailing value, rhetorically expressed as “tempering unbridled power,” yet to undertake research on what means to this end will fit a context “where the institutions typically thought of in connection with the ROL in domestic circumstances don’t exist in the international arena.”Footnote 56

2 Procedure and Rules

If the multiple discourses of ROL could arguably be convergent on a generic ideal of checking power, the procedures and rules within the UNSC offer a midlevel of doctrinal specification where empirical research can disclose whether discernible rules or implicit rule-bound actions reflect the higher ideals in ROL discourse.Footnote 57 At this midlevel, principles and rules can be layered. In their policy proposals to the UNSC in 2016, Farrall, Charlesworth, and Ryan advance a responsive model of the ROL centered on four basic principles: transparency, consistency, accountability, and engagement.Footnote 58 However, they extrapolate directly from these to specific recommendations that might be construed as rules.Footnote 59

For ROL recommendations-cum-rules internal to the UNSC, for instance, they propose, under the principle of transparency in peace operations, that “[w]hen the Security Council creates or modifies a peace operation mandate that seeks to strengthen the rule of law, the Council should ensure that the mandate clearly identifies the operation’s central rule-of-law objectives” (Recommendation 10, p. 43). Under the principle of accountability as it is applied to UNSC use of force, they recommend that the UNSC adopt a practice, or operational rule, whereby “[t]he Security Council should request regular briefings by states and groups of states implementing use of force mandates” (Recommendation 57, p. 48).

For ROL recommendations-cum-rules external to the UNSC, on peacekeeping, in adherence to the principle of transparency, they propose that “[t]he Security Council should request the Secretary-General to undertake periodic qualitative and quantitative monitoring and evaluation of each peace operation’s rule-of-law objectives (Recommendation 12, p. 43); and in keeping with the principle of accountability, they propose that “[w]hen the Security Council establishes or extends the mandate of a peace operation, it should emphasise the need for troop-contributing countries to ensure accountability for the investigation and prosecution of allegations of serious crimes by their troops” (Recommendation 19, p. 44).

3 Structures

The ROL as an institutional configuration within states is conventionally understood to require countervailing institutions that divide power and balance it among them. Whether through a separation of powers among executives, legislatures, and judiciaries, or a division of government between federal and subsidiary centers of government, or variants on fracturing power within the state and balancing it with forces outside the state, this structural element of ROL appears integral to its ability to temper power. This, of course, raises the vexing question: Is it empirically, theoretically, or normatively acceptable to extrapolate from institutional configurations within a state to the global order writ large?

Can we treat the UNSC as such an extrapolation? Critics of the UNSC’s wide-ranging powers have argued that the Charter permits it to act above the law,Footnote 60 even enabling it to engage in imperialism.Footnote 61 While the UN’s founders might have anticipated that two of the UN’s other primary organs – namely, the UN General Assembly and the International Court of Justice – would play the roles of global legislature and judiciary, thus balancing the UNSC’s executive mode, the Charter system falls short of a meaningful separation of powers. Indeed, as Chesterman has persuasively argued, the UNSC’s practice in the Cold War era reveals instances of the UNSC itself acting in executive, judicial, and legislative modes.Footnote 62 Nevertheless, the process of structural differentiation, with a prospect of allocating power to different social entities across different mandates of the UNSC, may open up a line of inquiry to appraise such prospects within the UN itself.

Internal to the UNSC we observe minimal and fragile, but discernible, structures that may contribute to UNSC accountability and transparency, among other principles. Eight social entities of one or another kind have been created to advise, enable, and monitor the UNSC’s ROL initiatives.Footnote 63 To what extent do they perform purely executive functions without any degrees of freedom, or can they exert de facto limits or influences on UNSC actions? For instance, the sanctions committees display variations in their adherence to ROL norms in the procedures and working methods they adopt to execute UNSC imposition of sanctions, to administer exemptions, and to evaluate humanitarian impact, among others. For a time, a Working Group on General Issues of Sanctions convened to produce recommendations to improve the effectiveness of sanctions. Bodies of experts are created for each sanctions regime. Since 2003 on Liberia, and subsequently on Iraq, UNITA, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan/Al Qaida and Sudan, among others, they have become institutionalized and tasked with investigation of implementation and violations of sanctions. The experts are usually based in their home countries and undertake field missions to sanctions sites. Complementing them are monitoring bodies, based at UN headquarters in New York, and staffed by UN civil servants. They track implementation of sanctions and report periodically to the relevant sanctions committee. They tend to have a higher status and are more institutionalized than other expert bodies. None are permanent. Their terms and mandates are extended from time to time until the sanctions regime is terminated.

The most important of subsidiary or partially differentiated bodies within the UNSC may be the formation of the Ombudsperson’s office in the sanctions regime.Footnote 64 Established in 2009, this office was created to deal with applications by individuals and other targeted entities for delisting by the UNSC.Footnote 65 Notably, its creation emerged from a series of criticisms after 1999 on the lack of due process in the sanctions regimes. Concerns expressed by many member states obtained legal impetus when the European Court of Justice brought its international juridical authority to bear in the litigation over the Kadi case.Footnote 66 Here, a global body, the UNSC, hitherto for the most part unchecked by any judicial body of comparable jurisdiction, was prompted to improve the fairness of its sanctions procedures due to a decision by a court with a notable regional, but no global, jurisdiction.

Prost,Footnote 67 a serving Ombudsperson for the Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee, has asserted that the Ombudsperson’s office “represents an important step forward in terms of enhancing the rule of law at the international level.”Footnote 68 In her 2016 stocktaking, she maintains that elements of fairness and due process have been introduced, with varying degrees of success, in four aspects of the Ombudsperson’s proceedings: sharing evidence with petitioners of the case against them; giving them an opportunity to answer the charges in that case; seeking to obtain a more independent review of information salient to a case; and undertaking all this in a “fair and timely process.” These practices address the third source of arbitrariness identified by Shaffer and SandholtzFootnote 69 – the need for individuals, or states, to question and respond to the way in which power is exercised over them. Nevertheless, Prost also concedes limits to transparency and fairness within proceedings, while confronting the fundamental underlying condition that the UNSC has kept the Ombudsperson’s office on a series of temporary extensions rather than giving it any kind of formal continuity and independence.

External structural and institutional tempering of power cannot come from arbiters external to the UNSC. While some international courts have addressed ROL issues in sanctions regimes, these instances are rare and haphazard, as no court exerts systemic or coherent constraints on the UNSC, even if they potentially influence its internal politicking and structural adaptations. Yet external structural expressions of UNSC ROL can be seen in certain issue areas where the UNSC seeks to get beyond itself: to temper power more directly through its peacekeeping forces; to set up or enhance existing structures to ensure that UNSC sanctions regimes, among others, do not abrogate ROL norms that apply to vulnerable populations; and to build ROL institutions within countries. Quite apart from the relative effectiveness of any of these modest extensions of ROL outside UNSC deliberations themselves, they nonetheless may be readily subverted by a perceived lack of adherence by the UNSC to ROL, as we have noted, whether in its internal deliberations or in its wholesale assertion of force by P5 states in seeming disregard for legal processes that would constrain naked power in pursuit of national interest.

V Transnational Legal Order

The comparative and interdisciplinary project on transnational legal orders seeks to elaborate a systematic framework for building empirically grounded theory on the ordering of law beyond the state. There are increasing indications that TLO theory enables scholars from many disciplines to hold in creative tension the rise and fall of a startling diversity of legal orders beyond the state that purport to solve social problems as unlike as climate change and inhibitions to lending, anti-money laundering and post-conflict resolution, fiduciary relationships and double taxation, constitution-writing and failing businesses, among many others.Footnote 70

The double confounding of rule of law and the UN presents a special challenge. On the one side, the rule of law, a long and amorphous tradition of thought, institutions, rhetoric, and investments, seems constantly to resist encapsulation in theory or practice. On the other side, the sheer vastness of the UN, and its ubiquitous presence or shadow over every international arena, presents a research site so bewilderingly entangled that empirical work invariably falls short. Since ROL, in one or another of its familiar academic formulations, can be found in all the UN’s conventions, and no sphere of human behavior falls entirely outside the UN’s reach, their conjunction presents a rare challenge to socio-legal scholarship.

For these reasons, as we intimated earlier, we sharply constrict our focus to the apex of the UN as an institution – the UN Security Council – and to ROL in the UNSC’s deliberations and three of its mandates. Now we begin to explore whether the lens of TLO theory, and its accumulating evidentiary base, can create some meaning, clarity, or coherence where a universal discourse encounters a universal institution.

Three conceptual aspects of TLO come immediately to the fore. First, whereas much other work on TLOs reaches to regional and global orders on trade or human rights or crime, transnational may also be understood as a legal order occurring among nations within a given transnational arena such as the UNSC (compare UNCITRAL) – that is, the order applies both to the object of the lawmaking and the lawmaking process itself. Second, the nomenclature that emerged inductively from earlier TLO studies pointed to the merits of imagining, identifying, and researching scales of TLOs. In climate change, for instance, one may point to a meta-TLO (e.g., the Paris Agreement), various mega-TLOs (e.g., within the EU), and micro-TLOs (e.g., agreements on greenhouse gas inventories and maritime transport emissions), as Bodansky notes.Footnote 71 Rajah proposes, in fact, that “transnational rule of law discourse may be seen as a meta-TLO that frames and contextualizes all efforts to manage and regulate … conceptions of legality in the sphere of the transnational.”Footnote 72 We view the competing visions of ROL in the UNSC as a struggle over the scope and substance of three micro-TLOs on peacekeeping, sanctions, and force, yet each is also nested within a meta-TLO on ROL that presses the UNSC to attain its highest ideals and core principles.

The logic of TLO theory begins with a presenting problem, growing gradually through facilitating circumstances and then sharply through a precipitating event, which energizes social actors to seek a solution through transnational law. That problem is framed in a particular way that lends itself to a particular legal solution. Through a series of recursive moves over months or years, between local, national, and transnational levels of action, and driven by four mechanisms (diagnostic struggles, actor mismatch, inconsistency, and contradictions), an order may emerge that is eventually institutionalized or settled such that a new set of legal norms come to be taken for granted as appropriate bases for action, and they are mutually reinforcing by concordance in transnational, national, and local law. This TLO may be more or less aligned with an underlying problem, or it may overlap, compete, or coexist with other TLOs or forms of order that strive for normative primacy.

The speech to the UNSC by Kofi Annan on September 23, 2003, is a marker for ROL as an explicit normative framing for UN action. It follows fourteen years of post-Cold War reconfigurations in the world geopolitical order with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the civil wars in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, military and other conflicts in many regions, and a massive enterprise of economic and political development in the 1990s. If collapse of command economies in favor of economic liberalism, the exhaustion of authoritarian regimes in favor of democracies, and the repudiation of rule-by-law regimes in favor of rule of law all heralded, “the end of history”, in a now sadly ironic expression of hubris, then the shock of 9/11 and the US and UK invasion of Iraq suddenly precipitated a global reappraisal of military force exercised by the world’s hegemon and the questionable status of the UN as a peacekeeper of last resort. While we cannot point definitively to 9/11 and Iraq as the trigger for the Secretary-General’s launch of the ROL agenda for the UN, it is striking how widely he throws down a gauntlet and how instantly he restricts it to a narrow strand of UN endeavors: “This Council has a heavy responsibility to promote justice and the rule of law in its efforts to maintain international peace and security. This applies both internationally and in rebuilding shattered societies. It is the latter that I wish to speak about today.”Footnote 73

The problem at large confronted by the UNSC just six months after the US invaded Iraq is construed generically as the need “to maintain international peace and security.” But Annan instantly retreats to the much safer terrain of “rebuilding shattered societies.” If ROL writ large was shunted aside in the extraordinary events that led to the UN’s inculpation in the Iraq War, Annan invoked the ROL writ small, seemingly to keep law, not war, as a prevailing ideal of international conflict resolution, and as a practical tool in very specific domestic trouble spots. From this moment, the ROL agenda writ large radiates across the institutional landscape of the UN in ways far beyond the scope of this study. The UNSC’s continuing formal engagement with that agenda is captured by Appendix I, which tabulates the evolution from 2003 to 2020 of the Council’s thematic meetings dedicated to ROL issues.

1 Micro-TLOs in the Making?

A more precise grasp on ROL in the UNSC may be obtained by narrowing attention to the construction of three micro-TLOs – one on each of the UNSC’s mandates for peacekeeping, sanctions, and force. Arguably, these micro-TLOs in formation are vehicles for conforming the UNSC’s deliberations as a whole, both symbolically and as practice, to the meta-TLO expressed by its discursive proponents within and beyond the UN.

From 2000 to the present, we observe several successive, somewhat interconnected, initiatives to create a legal order in the UNSC that adheres to more explicitly articulated ROL procedural and structural norms. Nevertheless, the respective initiatives differ in their prescriptions. A TLO analysis begins to disentangle some of those convergences and divergences as an incipient episode of TLO-making that has unfolded since 2000.

An initiative, from the years 2004–08, began through cooperation between the government of Austria and NYU’s Institute for International Law and Justice (hereafter Austria/NYU). A subsequent initiative, in the years 2010–16 and beyond, was led principally by socio-legal scholars at the Australian National University and the government of Australia (hereafter Australia/ANU). Each resulted in a report delivered to the UN, included in UN proceedings, and delivered to UN forums. Thereafter, a continuing effort has been mounted to influence ROL in the UNSC by mobilizing elected UNSC members to exert their influence in ways not adequately recognized or mobilized until more recently.

The construction of TLOs, small or large, begins with a presenting problem purportedly to be solved by law.Footnote 74 Each of the initiatives from below were animated respectively by the research of Chesterman on international humanitarian intervention, UN state-building and global administrative law,Footnote 75 and Farrall’s work inside the UN Secretariat and research on UN sanctions and post-conflict peacebuilding.Footnote 76 In all cases they observed deficits in UNSC decision-making, which subverted its legitimacy and probable effectiveness, and pathologies in UN practices in the field. In each case they observed manifest deviations from at least the spirit of high ROL ideals, and in each case it appears their initiatives were triggered by the explicit ROL turn in discourse as it was expressed in Kofi Annan’s 2003 speech and the UK’s effort to put ROL more prominently on the UNSC’s agenda. Significantly, in both cases the push for transnational reform came from ‘below’ and in a partnership of state and nonstate institutions.

Insofar as diagnostic struggles are an integral element of recursive cycles in the rise and fall of TLOs, we observe convergence and divergence. The earlier and later cycles of ROL-making share the view that UNSC-authorized operations fail frequently in their administration of sanctions, their control over peace-keeping forces, and their harms to vulnerable populations, such as women and children. Austria/NYU, however, approaching these problems from a global administrative law frame, diagnoses the problem as a failure of the UN essentially to adopt an institutional and procedural configuration of ROL that is conventional in well-established ROL orders within states. Failures are structural insofar as the UNSC and UN as a whole have not adequately differentiated the legislative, judicial, and executive functions and made the UNSC sufficiently accountable to a global judiciary. The UNSC has insufficient barriers to check what too easily can be abusive power. Australia/ANU, approaching these problems from a more socio-legal and regulatory governance perspective, observes a similar scope of UNSC breaches in the ROL, with particular attention to the deficiencies of sanctions regimes.Footnote 77 While Australia/ANU can concur with the Austria/NYU depiction of the global order as deficient in institutional configurations that are morphologically parallel to those within states, it departs from the Austria/NYU in its appraisal of where the fulcrums of change can be found and in the realism of what prescriptions might follow.

A driver of TLOs in formation or reformation frequently is actor mismatch – those actors who write and promulgate the global norms are not inclusive of all the actors essential for implementation. Those left out use their powers of resistance or noncompliance or governance-skepticism to subvert international norms. It can be noted that in both the Austria/NYU and Australia/ANU proposals for ROL reforms in the UNSC there is an alliance of relative outsiders to the P5 power configuration within the UNSC. Austria used Chesterman’s report and the buildup to it to build its legitimacy and case for election to the Council in October 2008, prior to serving on the Council in 2009–10. In Australia’s case, its campaign for ROL reforms extended from a similar bid for UNSC elected membership, through the benefits amplified by Australia’s UNSC membership in 2013–14, where the Australia/ANU conferences on ROL in New York could profit from greater access to key players in and around the Council, including some P5 diplomats (US, UK), and to follow-through after Australia stepped off the UNSC. Put another way, whereas Austria/NYU rode an electoral bid before membership, Australia/ANU rode a rising wave into the UNSC, a bigger wave during UNSC membership, and then the longer wave of postmembership legacy protection.

Close analysis reveals two further differences. The Austria/NYU initiative is driven by a small state in cooperation with an academic institution. It is true that its many conferences during the years 2004–08 include numerous senior international law scholars, former senior and some serving UN officials, experienced former judges in international tribunals, and numbers of diplomats from small countries, but it is a configuration principally of outsiders to the UNSC and it has none of the force of P5 members. The ANU initiative several years later similarly mobilizes states and nonactors in its series of consultations in Canberra and New York. The Australia/ANU cycle of reform consultations, however, involves actors of a different hue. The ANU alliance with the Australian government is forged through a partnership with a whole-of-government body dedicated to promoting civil–military coordinated responses to natural and man-made disasters in the Asia–Pacific region. By including the military, with areas of expertise essential to peacekeeping and force, there is a legitimating inclusion of an actor integral to UNSC operations. Moreover, from the beginning the ANU project not only aligned itself with Australia’s ultimately successful bid to become an elected member of the UNSC for the term 2013–14, but its reformist cycle embraced and ratcheted up the aspirations of that large number of states that aspire to an elected two-year term on the UNSC.Footnote 78 Further, the Australia/ANU proposal deliberately sought to translate the balance-of-power asymmetries between the P5 and E10 in the UNSC into a new idiom of UNSC debates, where ROL might present a common ground of discourse, procedure, and structure giving the E10 powers of persuasion that otherwise would be discounted or neglected.

The diagnoses and mix of actors in the Austria/NYU and Australia/ANU led to clear commonalities in principle in their respective sets of norms, but also observable differences. The fact that the Australia/ANU initiative could observe the substance and reception of the Austria/NYU proposals enabled the later cycle of proposed reforms and their propagation to adapt appropriately. To contrast each in broad brush strokes: Whereas the Austria/NYU report derived its recommendations from diffuse ROL norms, the Australia/ANU report explicitly articulated four master norms,Footnote 79 themselves revised from an earlier set of five norms.Footnote 80 Whereas the NYU ordered its expansive recommendations on the presumption that a state-like separation of powers can be established beyond the state, the Australia/ANU report took a more pragmatic strategy, judging that reforms were only feasible and more probable if they were modest and able to be implemented within the constraints of extant UNSC procedures and structures. Whereas the Austria/NYU report recommended that its diffuse norms be applied to a scattering of UNSC-related operations, the Australia/ANU report tightened its application of its four sets of explicit norms to the three designated areas of sanctions, peacekeeping, and force, thus more sharply linking the application of particular norms to particular spheres of UNSC decision-making and operations. And whereas the 2008 launch of the Austria/NYU norms took place prior to Austria’s UNSC term, with the aim of bolstering the legitimacy of its UNSC candidacy, the Australia/ANU ROL recommendations were launched in 2016, with the cosponsorship of Australia, as a recent UNSC member, and Japan, as a current member, supported by the UN Secretariat’s ROL unit within the Executive Office of the Secretary-General, in a chamber of 100 or more diplomats and staffers packed into a UN conference room at UN headquarters – a launch explicitly embedded within the motivating frame of increasing the impact of elected members of the UNSC before, during, and after their terms of office.

From Farrall’s initial focus on sanctions, to a widening of scope in the Austria/NYU norms, to the tightening and linking of explicit ROL norms to particular UNSC procedures and operations, the iterative process of three cycles both reinforced the pressure for ROL norms and brought the impetus for change more forthrightly into a broader set of impulses in the UN for the vast majority of states to exert greater influence in the UNSC as elected members.

Thus, we should see the succession of the Farrall (2007), Austria/NYU (2004–08) and Australia/ANU (2010–16) initiatives not as independent moments of intervention but as successive recursive cycles of multiple TLO-building efforts, which together constitute an episode to identify and propagate restraining norms that temper inconsistent and arbitrary exercises of unbridled power too often displayed by the UNSC. Focused TLO-building of norms respectively for peacekeeping, sanctions, and force was premised upon and might also lead to an expansive conformity of UNSC deliberations to a meta-TLO on ROL.

In subsequent related work on the E10 Influence Project, a team of scholars from the University of New South Wales, ANU, and the University of Queensland have interrogated a basic assumption underpinning conventional understandings of how the UNSC works – namely, that all of the power and influence on the UNSC resides with the P5 and that the elected members (E10) are just there to make up the numbers.Footnote 81 Farrall et al. (2020) identify three examples in which E10 members, working either individually in specific UNSC terms or collectively across multiple terms or different members, have been able to shape UNSC decision-making, despite the fact that they do not possess the raw power epitomized by the veto power.Footnote 82 All three examples – Brazil and Responsibility While Protecting; Australia and the human rights situation in North Korea; and a broad, sustained coalition comprising successive E10 members and UN member states not on the UNSC for the establishment of the 1267 OmbudspersonFootnote 83 – represent attempts to rein in the UNSC’s propensity to undermine the ROL and thus to boost its capacity to strengthen the ROL.

The E10 Influence Project, like its predecessor, the Strengthening the ROL Project, has benefited from the engaged support of the Australian mission to the UN. The research team undertook multiple rounds of fieldwork in New York between 2016 and 2019, consulting widely with UN practitioners and diplomatic representatives in order to identify prospective examples of E10 influence. During this fieldwork, the Australian mission provided valuable strategic advice to the team, hosting multiple seminars, bringing the team in close conversation with current and candidate E10 members, on the opportunities and constraints facing the E10 when seeking to shape UNSC decision-making.

How then may we appraise this incipient TLO-making to tighten and sharpen ROL procedures and practices in the UNSC? Insofar as the ROL dimensions in Table 6.1 are salient to the UNSC, there is little doubt that the ROL came to be relatively institutionalized as a discursive frame and a standing agenda item for the UNSC, recurring repeatedly from 2003 to 2022 (Appendix I). The fact that the Austrian/NYU report and, even more, the Australian/ANU policy proposals on ROL could evoke growing attention by some P5 members, many E10 members, and states within the UN General Assembly in itself demonstrated a vibrancy of the ROL discourse in this global diplomatic context. Nonetheless, it is not uncontested. Russia, in particular, has in recent years resisted ROL items on the UNSC agenda. There is some evidence that some states may be adopting a discursive work-around, whereby they reach ROL issues but in the language of “accountability” or “justice,” among other less evocative terms.Footnote 84

In terms of the reception by the UNSC of the procedures and rules proposed by the Australian/ANU report, the clearest example relates to the accountability of UN peacekeeping operations. Proposal 20 states that: “When the Security Council establishes or extends the mandate of a peace operation, it should reaffirm that allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse must be investigated and prosecuted by troop-contributing countries.”Footnote 85 In the months following the distribution of the proposals,Footnote 86 the UNSC included a provision requesting troop-contributing countries to ensure full accountability for acts of sexual exploitation and abuse by their troops in eight separate resolutions renewing the mandates of eight different peace operations.Footnote 87 While it might be a stretch to claim that the UNSC would not have included this provision in these eight resolutions in the absence of Proposal 20, the fact that the UNSC did so at this moment indicates that the proposal was tapping into currents of change demanding greater ROL adherence by peacekeepers and their countries of origin.

The potentially most significant shift in constraining UNSC arbitrariness on sanctions came with the establishment of the Office of the Ombudsperson. The Australian/ANU report recommended that its temporary status be made permanent and that its restriction to one sanctions regime be expanded to others. De jure permanence has not happened; de facto continuity has taken place as the office has been extended to further terms. And just as a trigger event brought the office into being in the first instance, it is not inconceivable that another trigger event might ensure both its permanence and extension to other sanctions regimes.

VI Conclusion

We began with a conjunction – the apex of geopolitical power and universality of a legal discourse – and a conundrum: Can an operationalization of the abstract discourse of ROL temper the arbitrary or unbridled power that might be unleashed by the permanent five members of the UNSC? By focusing on three key UNSC mandates, and drawing on empirical observations inside reform initiatives since 2003, we have proposed that question can be constructively approached: first, by developing an analytic frame that more precisely delineates dimensions of ROL in the particular context of the UNSC, and second, by adopting the systematic framework of transnational legal order which draws seemingly discrete or disconnected actions into a temporally sequenced and dynamic account of cumulative action to effect change in a normative order.

We conclude with some provisional observations. First, the discourse of a meta-ROL order can be operationalized in an empirically observable effort at micro-TLO constructions directed inside the UNSC. Those recursive cycles build upon each other to produce a widely accepted frame of lawmaking, which in turn is concretized in specific rules and procedures, being reflected in structures, none highly consequential in themselves, but all cumulatively indicative of momentum toward a now explicit set of norms for decision-making and action by the UNSC. In these senses, the micro-TLO-building represents a tactical shift from what Krygier characterizes as the “emptiness” and “conceptual unclarity” of ROL abstractions to particularities and activities adapted for the singular context represented by the UNSC. Arguably, this momentum reflects a countercurrent to retreats from international rule of law documented elsewhere.Footnote 88 Shaffer and Sandholtz ask what might be done to return to a “virtuous transnational cycle” that advances the ROL.Footnote 89 The reform movements within the UNSC, which we have analyzed through the lens of TLO theory, represent one possible avenue of instigating such a cycle.

Second, there endures a tension between the idealistic view of a classic institutional balancing of powers beyond the state and a pragmatic view that accepts this as a bridge too far. Again, we find Krygier’s framing on point. In contrast to the leanings of the Austrian/NYU initiative toward the replication and extrapolation of a within-state institutional separation of powers into the transnational realm, the Australian/ANU iteration of reforms proceeds on the basis of the judgment that a macrocosm of the national in the international would require amendments to the UN Charter – a prospect so unrealistic as to be a nonstarter. The perfect would become the enemy of the good. Why should we expect a global institution to achieve in decades what has taken many countries centuries to accomplish, nations still manifestly confronting the forces that will subvert ROL given the seduction of arbitrary power? An incrementalism within the UNSC may parallel the centuries-long struggles among centers of power within states as exceedingly uneven paths to ROL unfolded through revolutions, civil war, and intense political struggles. Hence, the Australian approach adopts a more realist expectation that ROL in the UNSC and its operations will probably be more effective when states themselves, especially the P5, with support or persuasion of some E10 members, draw their own ROL values into the UNSC. This takes the form of internalization rather than exterior pressure or moral suasion.

Third, by extending the ecology of UNSC-engaged actors from the P5 to the E10 and all other UN member states, ROL as an ideology takes on another hue. We postulate that the ROL is an idiom of legalism by which weak states – those outside the P5 – seek to convert their relative political impotence into a force for influence where ROL offers a unifying basis to temper the raw political powers of the P5. In this sense, we agree with Shaffer and Sandholtz that “[d]emocratic participation in the determination of law’s substance is … a necessary complement to rule-of-law ideals.”Footnote 90 However, we emphasize the two-way nature of this relation at the transnational level. Not only does participation enhance the ROL, but the ROL provides an avenue through which weaker states can engage in legal rulemaking, using the frame of the ROL to exert influence. Like King John’s barons, individually weaker than the Crown, but together strong enough to compel the sovereign to yield power, the elected UNSC members, present or future, might wield a moral and legal authority to compel dominant and imperial powers to check their “wild power” and naked national interest in order to maintain some measure of their historical hegemony. Put another way, this raises the question of whether the P5 will find it expedient to make incremental reforms in order to maintain some modicum of their own moral authority. Although the micro-TLOs that have been proposed for the UNSC since 2000 appear far removed from the capacity to restrain imperial propensities of the UNSC, might they constitute small episodes in a long historical trajectory representing moments where the concerted and incremental actions of the relatively weak present modest constraints on the powers of the putatively strong?