Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Indians in Malaysia: The Social and Ethnic Context

- 2 Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism

- 3 Colonialism, Colonial Knowledge and Hindu Reform Movements

- 4 Hinduism in Malaysia: An Overview

- 5 Murugan: A Tamil Deity

- 6 The Phenomenology of Thaipusam at Batu Caves

- 7 Other Thaipusams

- 8 Thaipusam Considered: The Divine Crossing

- Conclusions

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

2 - Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 January 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Indians in Malaysia: The Social and Ethnic Context

- 2 Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism

- 3 Colonialism, Colonial Knowledge and Hindu Reform Movements

- 4 Hinduism in Malaysia: An Overview

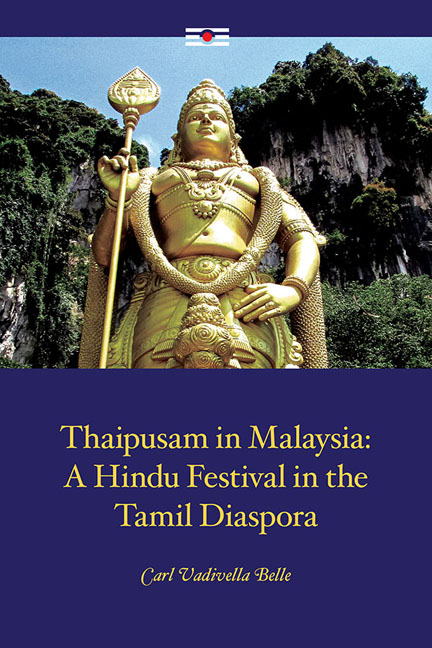

- 5 Murugan: A Tamil Deity

- 6 The Phenomenology of Thaipusam at Batu Caves

- 7 Other Thaipusams

- 8 Thaipusam Considered: The Divine Crossing

- Conclusions

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Summary

Most scholars would contend that Common Era India has contained two great and discrete hubs of civilization, each of which served the needs and reflected the aspirations of quite distinct peoples. Burton Stein has termed these hubs “Hindu Aryan India” (centred on the Gangetic Plains/Chambal Basin) and “Hindu Dravidian India” (South India defined as that portion of Peninsular India which falls south of the Karnataka watershed — excluding the modern state of Kerala in the west and the Kistna [Krishna]-Godavari delta in the east). Stein, following other scholars, asserts that the shared social, cultural and political histories of Hindu Dravidian India are such as to constitute it as a recognizable and sufficiently coherent unit for the purposes of study. He identifies the essential acculturating core of this region as the Tamil Plain and its immediate hinterland.

While the origins of the South Indian peoples remains speculative, archaeological evidence confirms that the Peninsula has been continually inhabited since very early times. This culture was given distinctive expression through, inter alia, the development of the Tamil language, which comprises one strand of a discrete linguistic family later known as “Dravidian”. The most ancient surviving Tamil writings, located in caves that were once occupied by Jain ascetics, date from the second century BCE and used Devanagari script common among Ashokan inscriptions found in North India. This suggests that even at this early juncture contacts between South India and the Gangetic Plains were well established.

South Indian Hinduism has developed its own distinctive societal mores, modes of spiritual inquiry and systems of philosophical speculation. This chapter will provide a general overview of the development of Tamil Hinduism and highlight some of its most enduring institutions and characteristics. This does not make any pretence to be an exhaustive historical survey, nor does it attempt to document all the detailed inflections of the many Hindu traditions and forms of worship located within the Tamil country (Tamilakam). The chapter will demonstrate that the continual reworking of Tamil Hinduism, especially the mutable boundaries of Agamic religion, provided multiple sites of particularistic religious expression, ranging from textual, philosophical and Agamic forms to those whose cosmologies inhere within the context of ritual and which may not recognise the putative authority of Brahmanic Hinduism.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Thaipusam in MalaysiaA Hindu Festival in the Tamil Diaspora, pp. 19 - 64Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2017