More than a conference or an alliance, the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America (Organización de Solidaridad con los Pueblos de Africa, Asia y América Latina or OSPAAAL) should be understood as an engine of radical cultural production that – for over four decades and in multiple languages – shaped and distributed a shared worldview of Tricontinentalism among a transnational, political community.Footnote 1 In From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism, and Transnational Solidarity (2018), I use “Tricontinentalism” to refer to a Cold War “political discourse and ideology” containing “a deterritorialized vision of imperial power and a recognition of imperialism and racial oppression as interlinked.”Footnote 2 This discourse, which circulated through the OSPAAAL’s cultural production and within related radical movements around the globe, intentionally avoided framing its global, political subjectivity through the language of class struggle. Rather, it employed “a racial signifier of color” to refer to “a broadly conceived transracial political collectivity” organized around a shared ideological position of Tricontinentalism.Footnote 3 The OSPAAAL’s conception of empire and resistance largely anticipated contemporary theories of racial capitalism, and its ideology of Tricontinentalism continues to reverberate within the contemporary Left.

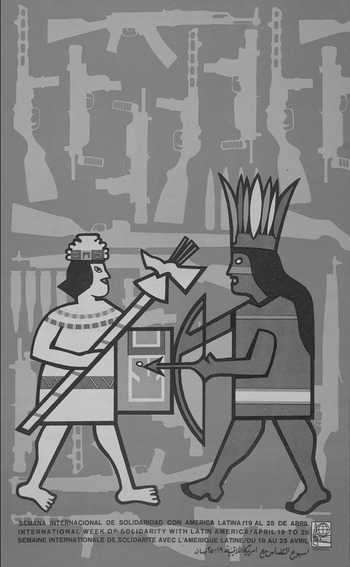

Figure 1.1 Tricontinentalism sought to legitimize revolutions by linking them to powerful cultural symbols and histories of local resistance in the Global South. This image is one of a trio linking contemporary weapons of war to iconography indigenous to each continent (as viewed from Cuba). OSPAAAL, Jesus Forjans, 1969. Offset, 53x33 cm.

Whereas From the Tricontinental to the Global South provides background for the emergence of Tricontinentalism, including the formation and inner workings of the OSPAAAL, the bulk of that study focuses on the period from the late 1960s to the present day. Building on this work, this chapter seeks to better define the ideological foundations for the OSPAAAL, framing it within the longer historical arc of the interwar League Against Imperialism and for National Independence (LAI) and arguing that it especially recovered core ideological tenets of the LAI’s understudied Americas section, the Anti-Imperialist League of the Americas (LADLA).Footnote 4

These two Latin America-based movements – the LADLA of the 1920s–30s and the OSPAAAL that began in the 1960s – arose out of distinct historical contexts, and this essay does not seek to draw a direct lineage in terms of the political activists involved in the two organizations. However, I trace five key ideological tendencies that they had in common in order to argue that although the OSPAAAL consistently rooted its history in the 1955 Asian-African Bandung Conference, it actually drew more closely from the historical memory of the LADLA.Footnote 5

The LADLA, which eventually included eleven chapters throughout the United States and Latin America, was created in 1925 in Mexico City. It brought together urban trade unions, agrarian organizations, and cultural and artistic groups across the two continents in a collaborative effort against US and European commercial and military expansion. Among its core leadership were several Cuban activists, most notably Julio Antonio Mella, living in exile in Mexico City.Footnote 6 Within two years of the LADLA’s founding, its members joined with 174 delegates, “representing thirty-one states, colonies, or regions” to form the LAI at the Congress against Colonial Oppression and Imperialism and for National Independence, held in Brussels from February 10 to 15, 1927.Footnote 7 This conference, organized by German communist Willi Münzenberg with limited financial support from the Comintern, focused primarily on the anti-imperialist struggle in China, India, and Mexico. However, delegates covered a broad range of issues during the five days of speeches.Footnote 8 There, LADLA organizers interacted with anti-colonial leaders from around the world, such as India’s Jawaharlal Nehru and Senegal’s Lamine Senghor. In Brussels, the LAI’s Executive Committee resolved that the LADLA’s continental organizing committee, based in Mexico City, would become the LAI’s “Central Organizing Bureau for Latin America.”Footnote 9

In rooting the OSPAAAL in the history of the LAI and in its Americas section (LADLA), I seek to correct a number of missteps in extant scholarship on both the OSPAAAL and the LAI. In both cases, problems arise from treating the 1955 Asian-African Bandung Conference as either the opening or the closing of a twentieth-century story of anti-imperialist internationalism. For instance, scholarship on the Tricontinental tends to frame its emergence as the first time that Latin American anti-imperialist movements entered into a global solidarity movement with a longer history in Afro-Asian anti-colonialisms.Footnote 10 The prevailing narrative positions the 1955 Asian-African Bandung Conference as the origin of both the Non-Aligned Movement and the more radical and Soviet-aligned Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization (AAPSO). The formation of the OSPAAAL in 1966 grew out of Cuba’s requests to join the AAPSO beginning in 1961, uniting Latin American anti-imperialist movements with prior Afro-Asian formations.Footnote 11

While this accounting from 1955 to 1966 is indeed accurate, beginning the OSPAAAL’s story with the 1955 Bandung Conference elides the much longer history of Latin American engagement with Afro-Asian anti-colonialisms through the LAI in the interwar years. Similarly, although the 1927 Brussels Congress, which founded the LAI, is widely viewed as a significant precursor to the Bandung Conference, extant scholarship on the Brussels Congress and the LAI tends to neglect the presence and contributions of Latin American movements there.Footnote 12 The scholarship of Michael Goebel and Daniel Kersffeld, who have each focused on Latin Americans’ participation at the Brussels Congress, is an important exception to this tendency.Footnote 13 However, generally, the LAI, as the precursor to the Bandung Conference, is most often understood in relation to Afro-Asian networks, reifying the false impression that the Tricontinental Conference represents the first entry of Latin American movements onto a global stage.

These problems lie not only with scholarship on the OSPAAAL since scholarship on the LAI tends to characterize the Bandung meeting as the endpoint of the LAI’s anti-imperialist internationalist vision from the interwar period, thus obscuring its connections to the later formation of the OSPAAAL. For example, Michele Louro’s excellent study, Comrades against Imperialism: Nehru, India, and Interwar Internationalism (2018), argues that “the Bandung Conference must be seen as a closure” to the LAI’s project in that “it marked the triumph of the nation-state and interstate relations in the arena of Afro-Asian politics, and it stood in contradistinction to the anti-imperialist internationalism of the interwar years.”Footnote 14 While the 1955 Bandung Conference – with its focus on representatives of nation-states – was indeed “distinct if not anathema to inter-war anti-imperialism,” ending the story in 1955 does not provide a complete portrait of the legacy of internationalisms begun in the interwar period.Footnote 15 Rather, the formation of the OSPAAAL recovered the LAI’s vision in significant ways, making it an ideological heir to the Afro-Asian-Latin American networks forged through the LAI. Specifically, the OSPAAAL recovered core contributions of the Latin American activists involved in this interwar, global organization through their participation in the LADLA.Footnote 16

The LADLA and the later OSPAAAL would share, I argue, five key ideological tendencies. First, both organizations advanced a global theory of imperial power in which resistant movements developed regional and hemispheric networks with the goal of bridging those regional connections to a broader, worldwide movement. Second, both sought to create a single theory of empire and resistance that would integrate histories of European colonization with twentieth-century patterns of economic domination through multinational monopolies and finance capital. Third, in constructing a political community across national and linguistic lines, both movements exhibited ideological openness and flexibility, incorporating diverse constituencies within a broad anti-imperial solidarity. Though both organizations are often understood as Soviet-backed communist movements, the reality was more complicated. Fourth, while both supported nationalist independence movements, they viewed the success of these movements as wholly dependent on structures of mutual support provided by internationalism. Finally, both took a stance of explicit anti-racism and ultimately intended to unite a global anti-capitalist movement with racial justice struggles in the Americas and around the globe.

Despite the similarities of the political projects of the LADLA and the OSPAAAL, they exhibited a major difference in that the LADLA, in its early years, demonstrated significantly less commitment to Black struggles and was more focused on organizing with Indigenous communities. After the 1927 Brussels Congress, where LADLA members interacted with African American activists and with anti-colonial movements from Africa and Asia, these encounters influenced a shift in the LADLA’s focus to issues facing Black and immigrant workers. While the OSPAAAL focused on Black struggles from its inception, it did so largely with respect to these struggles in the United States and South Africa, repeating a tendency of its predecessor to elide the problems of anti-Black racism in Latin America.

In what follows, I trace this longer arc of Latin American involvement in Afro-Asianism. Afro-Asianism influenced Latin American members of the LADLA, who especially identified with the agrarian focus of the Chinese communist movement. However, Latin Americans also brought their own ideas to the 1927 Brussels Congress. Specifically, Latin Americans brought direct experience with US imperialism and a nuanced understanding of how this form of foreign domination overlapped with and differed from the region’s prior encounters with European colonialism under the Spanish and British empires. As the US imperial project expanded around the globe over the coming decades, such an integrated theory of empire would form the basis for the later emergence of the OSPAAAL and for the central role that Latin Americans would play in it.

The LADLA and Interwar Internationalism

It is not coincidental that both the LADLA and the OSPAAAL – with their transnational understanding of imperial power that linked histories of European colonization with a more contemporary form of global capitalism – would emerge out of Latin America. While former Spanish colonies in the Americas had mostly secured independence by the end of the nineteenth century, independence did not eliminate the socioeconomic and racial hierarchies of these former colonial societies. This fact motivated the armed struggles of the Mexican Revolution, which preceded the Russian Revolution by almost a decade. Formal independence did not eradicate foreign intervention either as British finance continued to dominate in the region throughout the nineteenth century. With the US intervention into the Cuban War of Independence in 1898 and the repeated US occupations of Caribbean and Latin American countries in the early twentieth century, the United States would effectively introduce a new imperial project for the American hemisphere. In their “Resolutions on Latin America,” Latin Americans who attended the 1927 Brussels Congress wrote that “British imperialism is progressively ceding to Yankee imperialism.”Footnote 17 The United States, they explained, uses a “politics of penetration,” obtaining “the most important sources of primary materials and impeding the economic development of Latin American nations.”Footnote 18 In contrast to prior European forms of colonial expansion, which historically relied on the occupation of territory and the installation of a colonial ruling bureaucracy, the US imperial project was more focused on economic control than direct territorial sovereignty. This post-1898 model of US intervention in the Americas inspired Vladimir Lenin’s theorization of a new form of imperialism, what he called the “highest stage of capitalism,” in which multinational monopolies, through the cooperation of big banks and with backing by military power, eventually dominate the global market.Footnote 19

Lenin’s notion of imperialism appealed to many interwar Latin American radical thinkers, who theorized points of similarity between prior experiences of colonization and US economic domination. It played an important role in the establishment of the LADLA in Mexico City in 1925, which primarily sought to counter US and European commercial and military expansion in Latin America. The LADLA emerged as the Comintern was developing parallel strategies both on Latin America and on Black labor in the Americas more broadly. In this vein, it aimed to form a hemispheric, multiracial alliance that united Latin American workers with those in the United States.

The LADLA was conceived as a “mass organization” based on the Comintern’s united-front approach of the 1920s, and it sought to unite a broad range of social classes and leftist ideologies behind a position of anti-imperialism.Footnote 20 Eventually developing branches in several countries throughout the hemisphere, the LADLA’s membership relied on communist networks already in place in Latin America but intentionally avoided direct overlap with local communist parties, developing a broader collectivity of artists, intellectuals, noncommunist members of trade unions and nationalist organizations. Its headquarters in Mexico City included well-known politically conscious artists and intellectuals of the moment, such as Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, Xavier Guerrero, and David Siqueiros; US activists Bertram and Ella Wolfe; exiled Cuban political leader Julio Antonio Mella; and Italian-American photographer Tina Modotti.Footnote 21 It was started with the help of Scottish-born union organizer in Chicago, Jack Johnstone, who was sent to Mexico City for this purpose by the US Workers Party in 1924.Footnote 22 By 1926, its secretariat included multinational representation from each of its various national sectors.Footnote 23 In its early years, the Mexican labor leader Úrsulo Galván Reyes served as director of the LADLA’s periodical, El Libertador, with Mexican Nahua artist Xavier Guerrero serving as administrator and U.S. activist Bertram Wolfe as editor.Footnote 24

The first issue (March 1925) of El Libertador explains the creation of the organization as the necessary response to the expanding economic and military domination of the United States over Cuba, Panama, Haiti, Dominican Republic, and Mexico. To counter this expansion, El Libertador states, Latin American workers must ally with US workers to form “a single anti-imperialist continental movement,” which could then “eventually perhaps save Europe, Asia, and Africa as well.”Footnote 25 In other words, the LADLA began with a hemispheric vision, but this hemispheric project was intended, from its inception, to build outward toward a global one.Footnote 26 The writers of El Libertador asserted that while the publication would focus primarily on the American hemisphere, it would report on movements around the world. As explained in El Libertador, for petroleum workers in a place like Tampico, Mexico, for example, it would be imperative to “seek out alliances with petroleum workers from Europe, Asia, and South America, since the capital of Standard and Royal Dutch Shell is international.”Footnote 27 A strike against these companies, El Libertador asserted, “in order to be effective, must become international.”Footnote 28 In this way, connecting workers’ movements in Latin America with internationalist labor structures already in existence, especially the Red International of Labor Unions, was one of the LADLA’s core goals.

The LADLA expanded on this global vision through the organization’s participation in the 1927 Brussels Congress. In a July 1927 article published shortly after the Brussels Congress in América Libre: Revista Revolucionaria Americana (Free America: American Revolutionary Magazine), a publication affiliated with the LADLA’s Cuban section, Diego Rivera acknowledged strong anti-US sentiment among Latin American workers. He argued that a semi-capitalist relationship existed between US and Mexican labor in which Mexican workers extracted primary materials for manufacture by US workers.Footnote 29 Within US-owned multinational companies, he explained, an increase in salary for US employees directly translated as depressed salaries in Mexico. Rivera argued that this dynamic could be found in all industrial countries and compared it to the relationship between British and Indian labor. Importantly, in identifying these divisions, he did not mobilize an attack against all US citizens, but rather insisted on the importance of fomenting a greater class consciousness that would transcend the US-Mexico border.

Because of the LADLA’s efforts to bridge national, geographic, and linguistic divisions, it maintained an ideological openness to any group that viewed itself as anti-imperialist. The second issue of El Libertador (May 1925) explained that the LADLA included “unions; farmworker and Indigenous leagues; political parties of workers and farmers that fight against capitalism and imperialism; student, cultural, and intellectual groups that have participated or shown their desire to participate in our struggle; anti-imperialist revolutionary juntas – like that in Santo Domingo and Venezuela,” among others.Footnote 30 In this sense, although it was largely funded through the Comintern, it was intended as a “mass organization,” conceived within an ideological fluidity that sought to address the practical realities of the region and to unify a broad swath of the Left under a banner of anti-imperialism. It aimed to balance internationalist and nationalist positions by arguing that national independence for “oppressed, colonial, and semi-colonial peoples” could be achieved only through the mutual support provided by internationalism.Footnote 31 In other words, self-determination could not be obtained fully by any one of these communities until it had been obtained by all.

The 1927 formation of the larger umbrella organization, the LAI, would reflect similar ideological fluidity, accommodating nationalist and noncommunist movements from the colonies and often resisting oversight and pressure from Moscow. This flexible and open stance was consistent with the Comintern’s united-front approach of the 1920s, seeking to ally with “bourgeois nationalist movements in the colonies as a means to encourage anti-imperialist revolution first, and class revolution later,” bringing together “socialists, communists, trade unionists, civil liberties reformers, pacifists, Pan-Africanists, and anticolonial nationalists.”Footnote 32 For the internationalists from the colonies who participated in the LAI, a commitment to such fluid solidarities with one another would endure, in some cases, beyond the Comintern’s 1928 decision to abandon alliances with nationalists.Footnote 33

In addition to the LADLA’s hemispheric vision that frequently opened onto a global one and in addition to its ideological openness, the LADLA maintained an explicit stance of anti-racism rooted in the belief that agrarian laborers formed the base of the anti-imperialist struggle. In its early years, the LADLA was especially concerned with allying with Indigenous populations within rural regions most impacted by extractive industries. Such a concern is clearly expressed, for example, in the article “The Indian as the Base of the Anti-Imperialist Struggle” (“El indio como base de la lucha anti-imperialista”), written by Bertram Wolfe and published in the July 1925 issue of El Libertador. In this essay, Wolfe, who was living in Mexico City at the time, argued that until Indigenous communities “enter into the struggle, the anti-imperialist movement is condemned to remain a mere literary tendency among intellectuals, a sterile struggle of pamphlets and books denouncing Yankee imperialism in the name of the ‘Spanish race,’ which does not constitute the race that numerically predominates in the countries most subjected to said imperialism.”Footnote 34 The very reason that US domination was so pervasive in Mexico and Central America, Wolfe maintained, was precisely because of the oppression of Indigenous workers by a domestic white and mestizo oligarchy. Wolfe called for the LADLA to reach out to Indigenous leaders, who could use their linguistic and cultural expertise to organize Indigenous anti-imperialist leagues among agrarian workers.

Despite its commitment to anti-racist politics, the LADLA’s vision for a multiracial community was primarily focused on the radicalization of Indigenous, mestizo, and white industrial and farm workers, and in its early years, it was generally silent on problems facing Black communities.Footnote 35 This silence is notable not only because of the development of the Negro Question in Comintern strategy at this time but also because the majority of the workers in US-owned companies in the Caribbean sugar-producing region, in the Panama Canal zone, and in the banana industry in Central America were Black. Some of these Black workers were national citizens of the countries in which they worked, but many of them were West Indian and Haitian migrant workers brought in as inexpensive labor by US companies like United Fruit.Footnote 36

Through the interventions of the Committee on the Negro Question at the 1927 Brussels Congress, however, the LADLA would eventually expand its vision to think more deeply about Black labor in the Americas. Although issues facing Black communities were not at the forefront of the Brussels Congress, the meeting played an important role in putting Black African activists – such as Lamine Senghor and James A. La Guma – in contact with Black Americans such as Richard B. Moore. This exchange in Brussels resulted in the production of “The Common Resolution on the Negro Question.” Minkah Makalani has characterized the Brussels Congress and the establishment of the LAI as playing a significant role in the history of twentieth-century Black internationalism, writing that “black Communists believed they had a venue where they could pursue the internationalist politics that continued to elude them even within the international communist movement.”Footnote 37 The LAI’s more flexible program and its efforts to minimize Comintern control allowed the LAI to become a space for Black internationalist organizing that attracted Black radicals from a range of leftist ideologies.Footnote 38

The speeches and resolution by the Committee on the Negro Question made an impact on the LADLA. Two members of the Committee on the Negro Question, including Moore, signed onto the Congress’s “Resolutions on Latin America.” These resolutions were written by Latin American representatives in Brussels who were not exclusively LADLA members. However, the resolutions, which were reprinted in the June 1927 issue of El Libertador, largely repeated the LADLA’s platform in framing Indigenous communities as disproportionately experiencing the violence of imperialist extractive industries. Yet in a way different from previous iterations of this position, the resolution argued that “[i]mperialist penetration in these countries has exacerbated the inequality faced by Indigenous and Black peoples, because of the concentration of land, since Black and Indigenous people constitute the vast majority of the agrarian population.”Footnote 39 Through this resolution, the LADLA would redefine its program moving forward to include anti-Black racism as a central part of the imperialist extractive economy, identifying both Indigenous and Black communities as key to the worldwide anti-imperialist struggle. Moreover, whereas LADLA had always identified US workers as potential allies, this resolution recognized that “the oppressed races are also our allies with the United States itself.”Footnote 40 By framing Black and Indigenous agrarian labor as the base of anti-imperialism, the LADLA would take a further-reaching stance of anti-racism than the Comintern, which sought to incorporate (but not necessarily center) these workers into a struggle of primarily industrial labor and which argued that racial inequities could be resolved through class struggle.

Alongside the “Resolutions on Latin America,” El Libertador also printed “The Common Resolution on the Negro Question,” accompanied by a photograph of Senghor delivering his speech at the congress. This document drew connections between Black labor in the United States, Africa, and the francophone and anglophone Caribbeans. However, regarding the hispanophone countries of Latin America, the resolution stated:

In Latin America, except in Cuba, Black people do not suffer the yoke of any special oppression. In Panama, the yankee intervention has transplanted the United States’ barbaric customs against Black people, and this is the same origin of social inequalities in Cuba. Social and political equality, as well as the cordial relations between different races in other countries in Latin America, prove that no natural antagonism exists between them.Footnote 41

This statement, printed originally in Spanish in El Libertador, represents a slightly revised version of the conference document in English. In this Spanish version, the LADLA editors offered Cuba and Panama as exceptions to the resolution’s general claim about Latin America.Footnote 42 Although the LADLA’s version at least recognized the existence of anti-Black oppression in Latin America, it claimed that it appeared only in Cuba and in Panama, where it was attributed to US influence, suggesting that other Latin American countries with Black native or Black migrant populations lacked such discrimination. This idealized and false understanding of race relations in Spanish-speaking Latin America reflects the LADLA’s nascent theorizing on this issue at this point as well as the absence of Spanish-speaking Black Latin American delegates in Brussels. Despite this, the Committee on the Negro Question made a strong impression and raised questions that would be vital for the LADLA moving forward. Importantly, “The Common Resolution on the Negro Question” articulated a relationship between imperialism and the ideologies of white supremacism and identified how racism curtailed representation of Black activists in anti-imperialist organizations themselves. This would have an impact on the LADLA, which not only began to recognize how imperialism impacted Black communities throughout the Americas, but also began to incorporate a fight against anti-Black racism as an integral part of its platform.

The relationship between Latin America and the ideas put forth by the Committee on the Negro Question would be advanced especially through the interventions of Afro-Cuban activist and LADLA provisional secretary Sandalio Junco. He would discuss these issues at back-to-back conferences in 1929: the Confederation of Latin American Labor Unions (CSLA) in Montevideo and the First Latin American Communist Conference in Buenos Aires. While the LADLA did not organize either of these events, the continental networks that it had worked to create since 1925 were clearly reflected in the participants. Junco had been living in exile in Mexico City since 1928 along with other Cuban exiles. He led an active political life there, serving as Provisional Secretary of the LADLA and occupying leadership roles in several other closely related organizations, including the Latin American Confederation of Labor and the Association of New Cuban Revolutionary Émigrés.Footnote 43 The conferences in Montevideo and Buenos Aires in 1929 were convened by different organizations – the CSLA and the Comintern’s South American Secretariat – but they were planned to coincide with one another and included many of the same delegates. At both meetings, the problem of racism within communist and anti-imperialist movements and the strategy of Black self-determination became topics of heated debate. Junco’s voice arose as central to these discussions, and he used the conferences to argue that Black labor represented a significant blind spot in the way that many Latin American radicals were conceiving of their project.

At the CSLA conference in Montevideo in May 1929, Junco presented a little known but foundational text of Black internationalism called “The Negro Question and the Proletarian Movement.”Footnote 44 He called for an outreach campaign to Black American workers and insisted on the need to address anti-Black racism among Latin American workers. Junco argued that Black Americans should be understood as both part of a larger oppressed class and an oppressed racial category and that the exploitation of Black workers could not be resolved solely through class struggle. He disagreed with many of the participants’ strict differentiation between Black and Indigenous experiences – directly challenging the Peruvian intellectual José Carlos Mariátegui on this point – and compared the racialization of Black Latin Americans with the more familiar examples of Indigenous peoples, US African Americans, and Haitian and West Indian migrant workers. In a specific example, he compared violent US segregation and inferior working conditions previously described by Black Pittsburgh miner and conference participant Isaiah Hawkins to his home country Cuba, claiming that the post-independence Cuban republic had not followed through on its own promises to Black Cubans and pointing specifically to ongoing racial discrimination in hiring practices. The US and Cuban cases, he argued, were indicative of the inequities faced by Black workers throughout the continent and were especially dire for Black migrant workers employed by US-owned companies in the Caribbean and Latin America.

Junco’s interventions made their way into the work of various leftist organizations in Latin America in subsequent years, especially the Comintern’s Caribbean Bureau and within the Cuban section of the LADLA and its publication, Masas (1934–35).Footnote 45 Although the Soviet Union began to backpedal on its commitment to Black liberation and anti-imperialism as it allied with colonial powers against the fascist threat leading up to World War II, these debates would have a much longer life. Specifically, Junco’s insistence on the importance of the Black freedom struggle would become central to another anti-imperialist movement a few decades later, the OSPAAAL.

The LADLA ceased all operations by 1935, two years before the closure of the umbrella organization, the LAI. Michele Louro has argued that the closure of the LAI “marked more than a transition” from anti-imperialism to anti-fascism since “it foreshadowed the demise of a broader internationalist moment,” a demise that would be demonstrated by the inter-state focus of the 1955 Bandung Conference.Footnote 46 Although Indonesian President Sukarno opened the Bandung Conference “by commemorating the earlier Brussels Congress in 1927 as a pioneering moment for Asian and African solidarity,” the Bandung Conference bore little resemblance to the anti-imperialist internationalism of the LAI.Footnote 47 The Cold War, Louro writes, “made impossible the ‘blending’ of communist and non-communist activism, as well as the heterogeneous and flexible solidarities that were easily constructed before World War II.”Footnote 48 However, the Bandung Conference was not in fact an endpoint to the LAI’s vision of internationalism. Rather, this vision continued to resonate during the Cold War through global advocates of Tricontinentalism and the formal institution (OSPAAAL) that sought to define the movement. In the OSPAAAL, we see a recovery of the LAI’s “heterogenous and flexible” project, and especially an engagement with the core contributions of Latin American organizers to this interwar project.

The OSPAAAL and Tricontinentalism

The January 1966 Tricontinental Conference was announced as “the first time in history that revolutionaries from three continents … representatives of anti-imperialist organizations from the most distant parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America” had come together for such a gathering.Footnote 49 This characterization reflects the extent to which Bandung’s Afro-Asianism had begun to eclipse the longer history of anti-imperialism, obfuscating the history of Latin Americans’ involvement in the 1927 Brussels Congress and the LAI. Despite this unrecognized prehistory, the Tricontinental alliance would have significant parallels with its predecessor.

The Tricontinental Conference and the formation of the OSPAAAL, as reported by the Cuban newspaper Granma, intended to forge a “strategy of the revolutionary movements in their struggle against imperialism, colonialism, and neocolonialism and, especially against Yankee imperialism” and to create “closer military ties and solidarity between the peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the working class, the progressive forces of the capitalistic countries of Europe and the United States, and the Socialist Camp.”Footnote 50 Through this goal, the Tricontinental Conference joined together movements from vastly diverse contexts and developed a broad definition of its common enemy of global imperialism, which combined the notions of settler colonialism (faced for example by the Palestinian struggle) and exploitation colonialism (such as in the Portuguese colonies in Africa) with a Leninist theory of imperialism. As Che Guevara declared in his 1967 “Message to the Tricontinental,” the OSPAAAL was called to create “two, three … many Vietnams,” a vision akin to Guevara’s foco theory of guerrilla warfare – where the efforts of small cadres of guerrilla fighters eventually lead to massive insurrection – but on a global scale.Footnote 51

As early as 1959, Castro was already exploring the possibility of overcoming Cuba’s growing isolation through relations with the Afro-Asian bloc, sending Guevara, for example, to Cairo in June 1959 to seek the diplomatic support of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Guevara’s meeting with Anwar al-Sadat, the Secretary General of the AAPSO, during this visit led to the eventual invitation for Cuba to attend future Afro-Asian conferences.Footnote 52 Within two years, a Cuban observer attended the Fourth Session of the Council of Solidarity of the Afro-Asian Peoples, held in Bandung in April 1961, the same month as the Bay of Pigs invasion.Footnote 53 There, the Afro-Asian group composed a resolution condemning the US-backed invasion of Cuba.Footnote 54 The 1962 ousting of Cuba from the Organization of American States (OAS) exacerbated Cuba’s need to seek friends beyond the Americas and to advocate to officially join the AAPSO, eventually leading to the 1966 Havana Tricontinental and to the formation of the OSPAAAL.Footnote 55

The AAPSO originated in the First Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Conference in Cairo in 1957, two years after the 1955 Bandung Conference. However, the OSPAAAL leadership consistently presented the OSPAAAL and the AAPSO as having been birthed in the historic Bandung moment.Footnote 56 Despite this claim, there are key differences between the 1955 Bandung Conference and later AAPSO meetings. Whereas the Bandung meeting had intentionally excluded the Soviet Union, the AAPSO included representation from the Soviets and the Chinese and lacked the same commitment to neutralism that is often attributed to the Bandung meeting. Similarly, while Bandung was a governmental conference made up of heads of state, the AAPSO included government officials but also nongovernmental representatives from leftist political parties and movements.Footnote 57 The Tricontinental alliance would generally follow the structure of the AAPSO, including heads of state as well as representatives of liberation movements.

Although the OSPAAAL presented itself as the continuation of the 1955 Bandung meeting, the Tricontinental marked a clear shift away from the development rhetoric, principles of nonviolence, and inter-state focus associated with Bandung and toward a commitment to global militant resistance by state and nonstate actors alike. Moreover, as I have argued elsewhere, “Tricontinentalism represented a shift from a Bandung-era solidarity, based around postcolonial nation-states and a former experience of European colonialism, to a more fluid notion of power and resistance” organized against intersecting colonial and imperial forms.Footnote 58 In this way, its internationalism looked much more similar to the interwar project of the LADLA than to the Bandung vision. Considering Cuba’s close alliance with the Soviet Union and announcement in 1961 of the socialist nature of its revolution and considering the profound influence of Marxism on many of the anticolonial and independence struggles represented at the Tricontinental, one might expect that the unity between these diverse movements would be described as a common commitment to communism and international class struggle. However, similar to the LAI’s commitment to ideological fluidity, the Tricontinental was not framed in these terms.

This aspect of the Tricontinental was largely due to key disagreements and compromises made in the initial founding of the OSPAAAL. Before merging with Latin American movements to become the OSPAAAL, the AAPSO had strong representation from both the Soviet Union and China, and many of the African and Asian delegates of this organization were closely affiliated with the Soviet-sponsored World Peace Council (WPC).Footnote 59 As detailed elsewhere in this volume, the worsening of Sino-Soviet relations caused deep fissures in the organization and, as described by an OAS report, “began to absorb the energies of the meetings and became the principal focus of attention.”Footnote 60 Planning for the Tricontinental was similarly shaped by Sino-Soviet discord, but in its inclusion of Latin American movements, the Tricontinental presented an opportunity to shift away from the binary power struggle that had characterized the organization thus far.

A proposal for the AAPSO to combine with Latin American leftist movements was initially presented by the Cuban observer at Afro-Asian meetings in 1961 and 1963, but disagreements over the sponsorship of its first conference stalled the conversations. The Soviet Union wanted the conference to be sponsored by the WPC and by Latin American groups affiliated with the WPC under the leadership of one of its vice presidents, Lázaro Cárdenas of Mexico. The Chinese sided, however, with Castro’s bid to host the conference. According to an OAS report, because of these disagreements, discussion was eventually transferred from AAPSO council meetings to a secret meeting from which China and the Soviet Union were excluded, held in Cairo in 1964 with Mohamed Yazid of Algeria (who was representing President Ben Bella), Mehdi Ben Barka of Morocco, the Cuban Ambassador to Algeria Jorge Serguera, and the Secretary General of the AAPSO Youssef El Sebai of the United Arab Emirates.Footnote 61 There, it was decided to move forward with the Tricontinental Conference, and at the Fourth AAPSO Solidarity Conference, held in Winneba, Ghana, in May 1965, Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah presented the formal resolution, as Castro had requested, to hold the conference in Havana in January 1966 to coincide with the seventh anniversary of the Cuban Revolution. The International Preparatory Committee was then composed at Winneba with six representatives from each continent, with Mehdi Ben Barka operating as Chairman of the committee until his October 1965 abduction and murder and the transfer of his chairmanship to Cuban politician Osmany Cienfuegos.Footnote 62

In the first meeting of the Tricontinental’s International Preparatory Committee in Cairo in September 1965, another disagreement arose between the Soviet Union and China over the composition of the Latin American delegations. This time, Cuba sided with the Soviets. Cuba presented a list of pro-Moscow parties and China a list of pro-Chinese groups. It was eventually agreed that “insofar as possible, there would be solidarity committees representing all leftist, anti-imperialist and liberation groups in each of the Latin American countries, but under the direction of the respective communist parties.”Footnote 63 In practice, this meant that Latin American communist parties had responsibility for inviting groups to the Tricontinental Conference but that those groups did not necessarily have to be communist in affiliation or in ideology. This established a precedent of ideological fluidity within the OSPAAAL that would be developed much more fully in OSPAAAL cultural production over the next several decades. Such ideological fluidity represents a significant recovery of one of the core contributions of the interwar LAI, which sought to bring together communists, noncommunists, and bourgeois nationalists in “a collective mobilization against imperialist powers and capitalist classes.”Footnote 64

Chief among the reasons that the OAS would describe the Tricontinental as “the most dangerous and serious threat” to the inter-American system that the OAS sought to create was “[i]ts unconcealed desire to create an effective propaganda impact by rapidly publishing a great quantity of documents, speeches, and informational material on the event, and widely disseminating these through all available media.”Footnote 65 In fact, although many smaller meetings and panels of OSPAAAL delegations were held over the next three decades, the entire Tricontinental movement met only once at the 1966 conference.Footnote 66 Instead, the OSPAAAL’s massive cultural production would become the primary site for communication between its delegations. Through its publications and films, and through the iconic posters for which it is now recognized, the OSPAAAL provided both physical and textual spaces in which diverse political groups came into contact, and its materials shaped and were shaped by the perspectives of the various delegations it represented.

The OSPAAAL had four official arms of propaganda: the Tricontinental Bulletin (1966–88, 1995–2019), published monthly in English, Spanish, French, and sometimes Arabic, which provided updates on liberation struggles, interviews, and statements from delegations; radio programs; the posters that were folded up inside of the bulletin; and the ICAIC Latin American Newsreel.Footnote 67 Although only these four are mentioned in Tricontinental Bulletin, it also produced books and pamphlets, and in August 1967, it began publishing a magazine in English, Spanish, French, and Italian called Tricontinental (1967–90, 1995–2019) that included speeches and essays by revolutionaries such as Che Guevara and Amílcar Cabral, as well as interviews and in-depth analyses of the political and economic contexts of each struggle.Footnote 68 The Latin American Newsreel, short films made by the Cuban Film Institute (ICAIC),Footnote 69 played weekly in Cuban theaters from 1960 to 1990 and were often distributed internationally, engaging themes such as the achievements of the Cuban Revolution and independence struggles in Vietnam and elsewhere.Footnote 70

Through these materials, in a way similar to the LAI and the LADLA, the OSPAAAL articulated its explicit commitment to a struggle against racism. The “General Declaration” of the Tricontinental Conference explicitly identified racial discrimination as a tool of imperialism and proclaimed “the complete equality of all men and the duty of the peoples to fight against all manifestations of racism and discrimination.”Footnote 71 Moving forward, OSPAAAL materials would focus on a struggle specifically against anti-Black racism, spotlighting apartheid South Africa and, especially in its early years, the African American freedom struggle in the US South. Despite consistently pointing to the United States as the quintessential representative of imperialist aggression, from the very beginning, the OSPAAAL identified the cause of African Americans as an integral part of its platform. In the materials published leading up to the 1966 conference, the Tricontinental’s International Preparatory Committee defined “support to the negro people of the United States in their struggle for the right to equality and freedom and against all forms of discrimination and racism” as part of the agenda for the upcoming meeting.Footnote 72

Although Robert F. Williams and performer Josephine Baker were the only African Americans listed as official attendees at the Tricontinental Conference, Williams drafted the conference resolution on the “The Rights of Afro-Americans in the United States,” along with the Jamaican, Indonesian, and Venezuelan delegates.Footnote 73 The full text of this resolution was printed in the August–September 1966 issue of Tricontinental Bulletin. A portion of it states:

[A]lthough, geographically Afro-Americans do not form part of Latin America, Africa, or Asia, the special circumstances of the oppression which they suffer, to which they are subjected, and the struggle they are waging, merits special consideration and demands that the Tri-Continental Organization create the necessary mechanisms so that these brothers in the struggle will, in the future, be able to participate in the great battle being fought by the peoples of the three continents.Footnote 74

In this statement, the OSPAAAL does not just express its support for African Americans but also explicitly brings them within the Tricontinental alliance.

This solidarity with the U.S. Black freedom struggle became more pronounced in the years following the Tricontinental Conference, as is clearly evinced by the many articles devoted to it in Tricontinental Bulletin as well as the many posters in solidarity with African American people that were folded up inside Tricontinental. In these materials, the Tricontinental maintained that African Americans were subject to the very same oppression that the delegations of the three continents were, and thus, not only considered African Americans to belong to the Tricontinental but – because they were said to be fighting within the belly of the beast of the imperialist United States – deemed them particularly representative of its global political subjectivity. In essence, the OSPAAAL framed the Jim Crow South as a microcosm of a worldwide, Tricontinental struggle.

Although the African American struggle continued to feature in OSPAAAL publications throughout the late 1970s and 80s and although the OSPAAAL expressed a commitment to anti-apartheid in South Africa from its very inception, OSPAAAL materials turned their focus from the US South toward southern Africa as Cuba ramped up its involvement in the Angolan Civil War. Whereas initially OSPAAAL materials consistently represented the US South as a microcosm of an expansive global empire characterized by racial capitalism, from the mid-1970s onward, apartheid South Africa became the fulcrum on which Tricontinentalist understandings of power and resistant solidarity cohered. For the next decade, OSPAAAL cultural production shined a spotlight on southern Africa with posters condemning apartheid and declaring solidarity with southern African liberation movements, articles by leaders such as Oliver Tambo of the African National Congress and Namibian politician Sam Nujoma, proclamations calling for the release of Nelson Mandela, analyses of South African military strategy in Angola, and reporting on anti-apartheid organizing around the globe.

Through the OSPAAAL’s focus on the struggle for Black freedom in the US South and South Africa, it expanded upon the LAI’s “The Common Resolution on the Negro Question.”Footnote 75 In centering Black liberation struggles, the OSPAAAL diverged from the LADLA’s primary focus on Indigenous movements, better incorporating African and African American perspectives to confront the problem of anti-Black racism. In this way, the OSPAAAL could be viewed as belatedly responding to Junco’s 1929 interventions on the so-called Negro Question. However, in his 1929 speech, Junco also called for an engagement with the oft-ignored inequalities faced by Black peoples in Latin America. Whereas OSPAAAL materials spotlighted Black struggles in places like the United States and South Africa, these materials exhibit a consistent silence regarding the conditions of Black peoples in Latin American countries.Footnote 76 Indeed, by effectively externalizing anti-Black racism to African and North American contexts, the OSPAAAL repeated a major error of both the LADLA and its umbrella organization, the LAI.

Thinking Tricontinentalism Backwards and Forwards

Tracing the full arc of the OSPAAAL’s history and legacy is crucial for understanding the Tricontinental movement. A discussion of Tricontinentalism without the larger framework of its deep roots in interwar internationalism fails to adequately address the way it responded to the accomplishments and missteps of the LAI’s interwar project. Placing these two movements together reveals that Latin America had a longer history of radical, global anti-imperialism than is often understood. Though sharing common goals, Tricontinentalism went further in embracing an anti-imperialism that linked anti-capitalism with racial justice, even as its solidarity with Black freedom struggles did not always produce self-reflection about the inequalities of Latin American societies. In the same way that we need to better understand the roots of Tricontinentalism, we must also look beyond the 1966 conference and beyond the immense propaganda of the OSPAAAL itself to comprehend the long-term implications of this political project. In addition to the scholarly importance of such an endeavor, studying the history and contemporary resonances of radical internationalisms, which includes examining the failures of these movements, is a vital baseline for forging global justice movements into the future.