Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- Preface

- A Note on the Use of the Term ‘Score’

- Glossary

- Abbreviations

- Plot Summary

- Casts of the First Performances

- Introduction

- 1 The Prague Don Giovanni

- 2 The Vienna Don Giovanni

- 3 The late eighteenth-century dissemination of Don Giovanni

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Error transmission

- Appendix 2 Page-break analysis

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- Preface

- A Note on the Use of the Term ‘Score’

- Glossary

- Abbreviations

- Plot Summary

- Casts of the First Performances

- Introduction

- 1 The Prague Don Giovanni

- 2 The Vienna Don Giovanni

- 3 The late eighteenth-century dissemination of Don Giovanni

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Error transmission

- Appendix 2 Page-break analysis

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

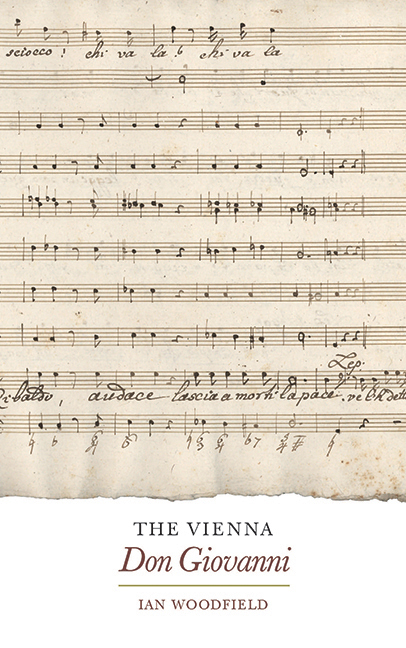

According to Da Ponte's famous account of the Vienna reception of Don Giovanni, everyone except the composer thought that the work was somehow flawed. Responding to the popular verdict, Mozart is supposed to have made alterations, but still his opera failed to please, and only after repeated performances did its true quality win recognition. The passage relating to Don Giovanni runs as follows:

The Emperor called me in and, showering me with gracious expressions of praise, made me a gift of another hundred ‘zecchini’, and told me that he very much wanted to see Don Giovanni. Mozart returned [and] immediately gave the score to the copyist who hastened to prepare the parts, since Joseph had to leave. It was staged, and – dare I say it? – Don Giovanni did not please. Everyone, except Mozart, believed that something was lacking. Additions were made, some of the airs [arias] were changed, it was staged again, and [still] Don Giovanni did not please. And what did the Emperor say? ‘The opera is divine; it is perhaps more beautiful than Figaro, but it is not food for the teeth of my Viennese.’ I recounted this to Mozart, who replied without becoming upset: ‘Let them have time to chew on it.’ He was not mistaken. I managed, on his advice, to get the opera repeated often: at each performance the applause grew, and, little by little, even the Viennese with bad teeth appreciated its flavour and understood its beauty, and rated Don Giovanni among the most beautiful operas that had been performed in any theatre.

In the absence of other evidence, this account has naturally had a strong influence on the way that the Vienna reception of Don Giovanni has been perceived in both scholarly and popular literature.

That there might have been changes of mind about Don Giovanni both before and after its Vienna première goes without saying. An eighteenth-century opera did not consist of a fixed text; rather it was a fluid, constantly evolving enterprise, subject to a significant (and growing) element of collective responsibility. This is unproblematic as a historical concept, but it causes obvious difficulties when the time comes to define the precise form of a work in a published text.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Vienna Don Giovanni , pp. 1 - 12Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2010