Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Main “Dramatis Personae”

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Guba

- Chapter 2 Winds of Change

- Chapter 3 Subjectivities on the Rise

- Chapter 4 The Clashes

- Chapter 5 Living Lives with Multiple Subjectivities

- Chapter 6 Engaging with the Sovereigns

- Conclusion: Sovereignty in Crisis

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Main “Dramatis Personae”

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Guba

- Chapter 2 Winds of Change

- Chapter 3 Subjectivities on the Rise

- Chapter 4 The Clashes

- Chapter 5 Living Lives with Multiple Subjectivities

- Chapter 6 Engaging with the Sovereigns

- Conclusion: Sovereignty in Crisis

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Summary

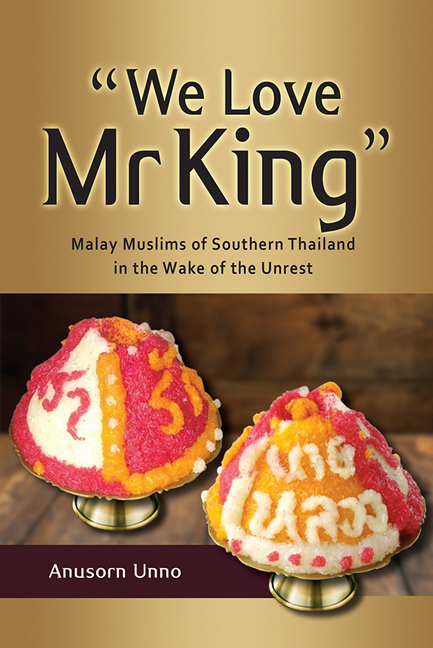

During a hot, breezy afternoon in Guba — a Malay Muslim village in southern Thailand — a schoolchild halted and reoriented a routine conversation at a roadside pavilion by bringing in a decorated, footed tray. The tray had been made for the opening ceremony and parade for Tadika Samphan, an intramural sports game among members of Taman Didikan Kanak Kanak (Tadika) in Raman district of Yala Province. The tray contained tricoloured sticky rice that inscribed a sentence, “เรารักนายหลวง” (rao rak nay luang), purposely meant to mean “We love the king”. It would not have drawn much attention from those at the pavilion if the word for “king” had been spelled as it should have been. Instead of “ในหลวง” (nai luang), “the king” — the most commonly used phrase for designating the Thai monarch — what was inscribed instead was “นายหลวง” (nay luang), a term that literally means “Mister Luang” and that, for Thai-speaking people, has nothing to do with the Thai monarch.

After my remarks on the title nay luang, the others at the pavilion had various reactions. Some were surprised and said they had never before realized that the nay spelling was incorrect, despite the virtual omnipresence of the phrase rao rak nai luang nationwide, especially after state-supported campaigns in 2006. Others — especially those who had been involved in making the decorated tray — seemed embarrassed, as they had been particularly attentive in making it, and it had already been displayed in the parade and at the official opening ceremony, where senior government officials had been present. “It should not have happened”, one of them said in disappointment. Still, although some wondered if the incorrectly spelled phrase nay luang could be considered blasphemous to the highly revered Thai monarch, most of them did not take the issue seriously, considering it a small mistake they could joke about among themselves.

The misspelled rao rak nay luang would have simply passed as an illiteracy issue, a failure of formal education, or an unintended consequence of the state's propaganda had it not been written by a group of Malay Muslims from southern Thailand, in a period when Malay Muslims were attempting to negotiate their subjectivity in questions relating to the state, their ethnicity, and religion.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- "We Love Mr King"malay Muslims of Southern Thailand in the Wake of the Unrest, pp. 1 - 11Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2018