Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.

It is time to move on to the central issue of this book: how our experience affects our wellbeing. The starting point is the huge inequality that exists in wellbeing – both within countries and between them. This is the most fundamental inequality there is – the inequality in the overall quality of life as people experience it. So we begin with the key facts about the level and distribution of wellbeing in the world.

The Level and Inequality of Wellbeing in the World

The best evidence we have on the worldwide distribution of wellbeing comes from the Gallup World Poll. This remarkable survey happens every year and covers nearly every country in the world. Around a thousand adults are surveyed in each country each year. They are selected to be as representative as possible of the population in each country, and, when necessary, the results are re-weighted to be as representative as possible. The interviews are conducted face to face in the poorer countries (at least before COVID-19) and by telephone in the richer ones.

The main wellbeing question is what is known as the ‘Cantril ladder’ that we described in Chapter 1.Footnote 1 In the years when Gallup also asked about life satisfaction, the answers to both questions were very closely correlated.Footnote 2 So we can think of the Cantril ladder as a standard evaluative question about wellbeing.

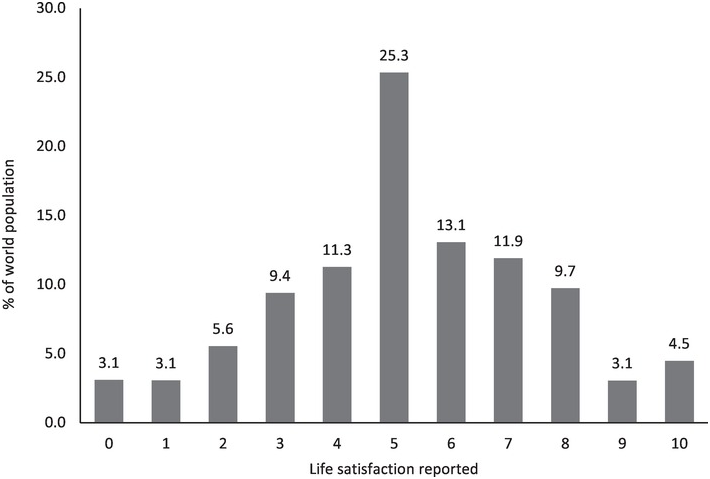

In Chapter 1, we already showed the averages for the different countries. But more important than differences between countries are differences between people. So Figure 6.1 shows the worldwide distribution of individual adult wellbeing before COVID-19, each individual being given equal weight. The spread is very wide – over a sixth of the world’s population answer 3 or below, while over a sixth answer 8 or above. This must be one of the most basic facts about the human condition on earth today.

Figure 6.1 Percentage of people in the world at each level of life satisfaction

There is also another way of showing this huge spread of wellbeing – the same facts laid out differently. In Figure 6.2, we break the population down into ten groups of equal size, starting with those who are the least happy on the left of the graph and ending on the right with those who are happiest. As the graph shows, the least happy have an average wellbeing of 1.1 points and the happiest have a wellbeing of 9.2 points. It is a world with many lives that are limited and a few that are truly flourishing. The average wellbeing in the world before COVID-19 was 5.3 points (out of 10) but the spread, as measured by the standard deviation, was 2.3 points.Footnote 3

Figure 6.2 Life satisfaction (0–10) of people at each decile of life satisfaction

But how much of this huge spread of wellbeing in the world is due to the spread between countries, and how much of it occurs within countries? The neatest way to answer this question is by taking the square of the standard deviation, known as the variance. We can then partition the variance of individual wellbeing worldwide into two elements:

differences within countries and

differences between countries.

It turns out that the difference between countries contributes only 22% of the overall variance and the main variation (78%) is within countries.Footnote 4 Thus the standard deviation of average wellbeing across countries is about 1.1, while the average of the standard deviation inside a country is about 2.3.

Changes Over Time

It is easy to think that we live in a peculiarly dreadful time. But this is not so, judged by the criterion of wellbeing. There are indeed some countries in which wellbeing declined between 2005–2008 and 2016–2018.Footnote 5 These include the United States, India, Egypt, Brazil, Mexico, Venezuela, South Africa and those affected by civil war. But there are as many countries where wellbeing has risen since 2005–2008 as where it has fallen. Countries where wellbeing rose include both China and most of the countries that were once Communist. Earlier on, between 1980 and 2007, wellbeing rose in more countries than not.Footnote 6 On balance, therefore, the world as a whole is probably as happy as it has ever been.Footnote 7

But progress in wellbeing is by no means automatic, and it is noteworthy that in some important countries, wellbeing is now no higher than it was when records began. In the United States, that means in the 1950s; in West Germany, it means in the 1970s; and in China, it means 1990. We shall discuss this issue more fully in Chapter 13.

By contrast, if we look at short-term changes in wellbeing over the business cycle, wellbeing generally fluctuates up and down around its trend – higher in the boom and lower in the slump. We shall also discuss this issue at length in Chapter 13.

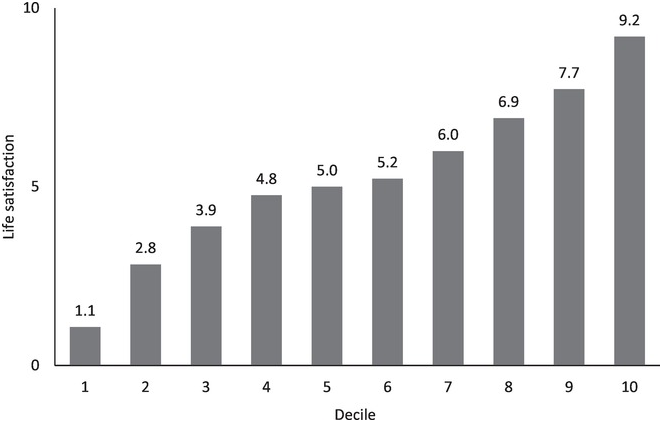

Meanwhile, how has the inequality of wellbeing been changing over time? In most countries, it rose between 2006 and 2018 with especially sharp rises in North America and Sub-Saharan Africa, which now have the highest levels of regional inequality (see Figure 6.3). However, wellbeing inequality fell in Europe, which now has the lowest levels of wellbeing inequality in the world.

Figure 6.3 Trends in the inequality of life satisfaction (0–10) (Standard deviations)

Hedonic Measures of Wellbeing

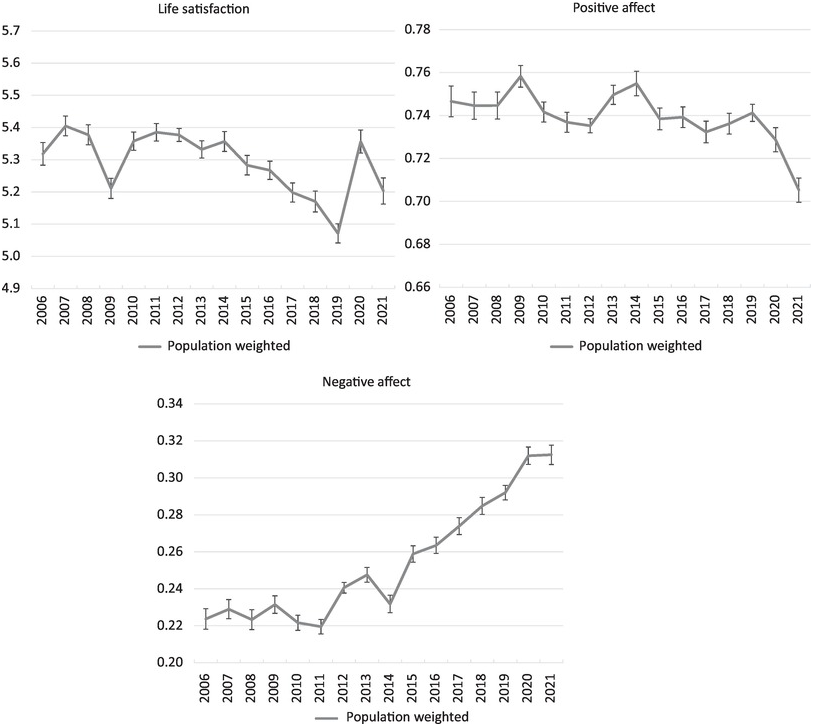

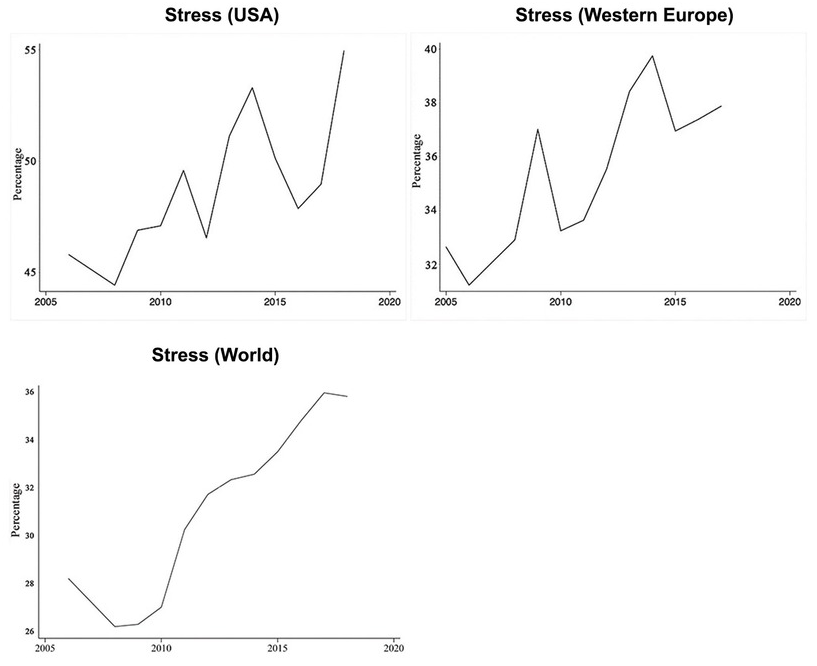

The analysis so far is based on the Cantril ladder. The Gallup World Poll also asks questions about people’s emotions – the hedonic measures of wellbeing that we discussed in Chapter 1. These questions give useful information about changes over time. At the world level, one can construct an index of positive and negative emotion, based on the question ‘Did you experience X during a lot of the day yesterday?’ For positive emotions, X includes separate questions about happiness, enjoyment, and smiling or laughing. These can be combined into a single index by taking the average proportion of people who said Yes to each question. Similarly for negative emotions – where the questions relate to worry, sadness and anger. Figure 6.4 shows trends at the world level for both positive emotion and negative emotion. As the figure shows, positive affect and the Cantril ladder have been trending down slightly. But negative affect has increased greatly – especially worry. This is confirmed by an additional question on stress where we reproduce the answers for the United States, Western Europe and the world as a whole in Figure 6.5. These findings are deeply troubling. But for the rest of this chapter, we shall revert to measures based on the Cantril ladder.

Figure 6.4 Trends in average wellbeing in the world

Figure 6.5 Trends in stress (Percentage saying ‘I experienced a lot of stress yesterday’)

Differences Between Groups

So how does average wellbeing differ between groups?

Men and women

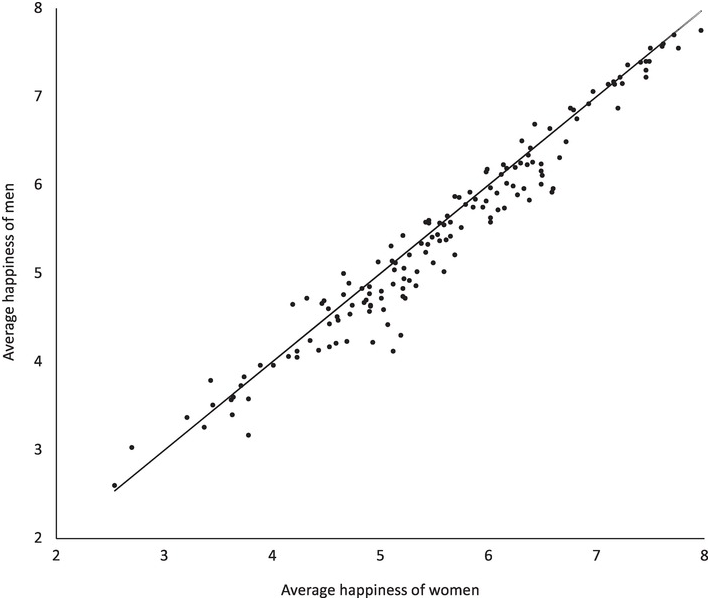

Remarkably, the distribution of wellbeing in the world is almost identical for men and women. Women are on average slightly happier than men but the difference is only 0.09 points (out of 10) – one fiftieth of the difference between the happiest and least happy country. Moreover, in almost every country the average wellbeing of men and women is nearly the same, even though wellbeing differs so hugely between countries (see Figure 6.6).Footnote 8

Figure 6.6 Average wellbeing of men and women: By country (the line represents equality)

But what about trends in the relative happiness of men and women? Over the last 50 years, women’s rights in the workplace have been transformed in many countries by legislation requiring equal pay and equal job opportunities. At the same time, women have made huge educational advances relative to men, and through the contraceptive pill have achieved unprecedented control over their fertility. So one might expect that women’s wellbeing would have risen relative to men’s. But has it?Footnote 9

In the United States since the 1970s, both men and women have become less happy, and this has been especially true of white women. In Europe, the situation has been different. Both women and men have become on average more satisfied with their lives, but European women’s happiness has fallen relative to men’s – and this has happened in all 12 countries for which the time series go back as far as the 1970s.

Why is this?Footnote 10 Empirical work has so far failed to produce an explanation. The most likely one (so basic to humans) is social comparisons. As more and more women work, they may increasingly compare themselves with their male colleagues (rather than with other women). And at work women are still frequently at a disadvantage. Another possibility is that women now experience a greater conflict of roles (as compared with men). The US evidence suggests that (up to 2005 at least) there was no change in women’s total work relative to men’s (total time spent in paid work, housework and childcare).Footnote 11 But that is not the same as the sense of responsibility. Women still do more work at home than men, and to that has been added much greater responsibilities at work. Another possibility is family conflict. In the United States, both men and women have become less satisfied with their marriages – and to an equal extent. But satisfaction with marriage affects women’s happiness more than men’s, and increased dissatisfaction with marriage therefore helps to explain the increased gender gap in US happiness.Footnote 12 Finally, there is the enduring fact of male chauvinism. Though this may have diminished over time, the experience of it may have become more intolerable – as the #MeToo movement testifies.

Age

The next issue is Do we become happier as we get older? The effects of aging involve many factors but social factors are among them. As we move into adult life, we take on more responsibility, both in family life and at work. But after some time, we become more established, and any children we had leave home. We relax more. But eventually our health declines. So what is the overall effect of our journey through life?Footnote 13

In most countries, people on average become progressively less happy from their late teens up to their 40s. But then in some countries (including the United States and the UK), they become happier again up to their 70s (before a final decline). Figure 6.7 shows how wellbeing changes over life in each of the world’s regions. Everywhere happiness declines up to around age 40. It then recovers in North America and to a lesser extent in East Asia; in Western Europe, it remains stable; but elsewhere, there are some further declines. (In the former Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact countries the old are markedly less happy, but this is the legacy of the transition and may not continue in future decades).

Figure 6.7 Average life satisfaction: by age, gender and region

Note: NA & ANZ = North America, Australia and New Zealand. CEE & CIS = Central and Eastern Europe and former Soviet Union. LAC = Latin America and Caribbean. MENA = Middle East and North Africa. SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa

So what explains these patterns of wellbeing over the life-course? If age affects wellbeing, it must be through some mediating variables.Footnote 14 But what are they? The first step is to look at the standard variables explaining wellbeing, which we shall consider in Chapter 8. From 20 to 40 years old, most of these variables are moving in the direction that would produce higher wellbeing. So they provide little insight into variation across the life-course.Footnote 15

More light can be found by looking at the Gallup World Poll’s evidence on affect. As we have mentioned, this provides data on negative and positive affect. Beginning with negative emotions (Figure 6.8), stress rises sharply up to middle age and then declines. So does anger, though less markedly. These declines after middle age are especially marked in North America and Western Europe. By contrast, worry, sadness, depression and pain rise steadily through life, but as time passes they become balanced by declining stress and anger. Turning to positive emotions (Figure 6.9), happiness, enjoyment, smiling and interest fall steadily throughout life. In addition, as people age, they are less likely to report that they have someone they can rely on in times of need. People do however feel more rested.

Figure 6.8 Negative Experiences: By age and gender (World)

Figure 6.9 Positive Experiences: By age and gender (World)

Ethnic differences

What about the differences between ethnic groups? In every society, most minority ethnic groups have lower average wellbeing than the majority group. But these differences can be reduced or even eliminated by policy action, such as

reducing gaps in education and income,

banning discrimination in employment and housing,

punishing severely both racially motivated crime and incitement to racial hatred and

improving the respect shown to all (by citizens, by the police, and by the law).

With such action, things can change. For example, the United States has seen substantial improvement in the wellbeing of ethnic minorities, while at the same time the average wellbeing of whites has declined.Footnote 16 This is shown in Figure 6.10, which is based on the General Social Survey. (The happiness scores used are very happy – 3; pretty happy – 2; not too happy – 1.) As Figure 6.10 shows, the gap in happiness between white and black citizens has fallen sharply.Footnote 17

Figure 6.10 Average wellbeing (1–3) of different racial groups in the United States

However, America still has serious ethnic problems, as the Black Lives Matter movement testifies. And so have most other countries, though the groups involved differ widely. In some countries, ethnic tensions lead to civil war.

The Wellbeing of Children

So much for adults; but what about children? In both 2015 and 2018, the OECD surveyed the wellbeing of 15-year-olds in their regular Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). The question asked was on life satisfaction (0–10) and the survey covered most OECD countries and a number of others. The results by country are in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Average life satisfaction of 15-year-olds (0–10)

| OECD Countries | Other countries | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 8.11 | Kazakhstan | 8.76 | |

| Colombia | 7.62 | Albania | 8.61 | |

| Finland | 7.61 | Kosovo | 8.30 | |

| Lithuania | 7.61 | North Macedonia | 8.16 | |

| Netherlands | 7.50 | Belarus | 8.10 | |

| Switzerland | 7.38 | Dominican Republic | 8.09 | |

| Spain | 7.35 | Ukraine | 8.03 | |

| Iceland | 7.34 | Costa Rica | 7.96 | |

| Slovak Republic | 7.22 | Saudi Arabia | 7.95 | |

| Estonia | 7.19 | Panama | 7.92 | |

| France | 7.19 | Romania | 7.87 | |

| Latvia | 7.16 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 7.84 | |

| Austria | 7.14 | Croatia | 7.69 | |

| Portugal | 7.13 | Montenegro | 7.69 | |

| Hungary | 7.12 | Moldova | 7.68 | |

| Luxembourg | 7.04 | Thailand | 7.64 | |

| Chile | 7.03 | Serbia | 7.61 | |

| Germany | 7.02 | Georgia | 7.60 | |

| Sweden | 7.01 | Uruguay | 7.54 | |

| Greece | 6.99 | Indonesia | 7.47 | |

| Czech Republic | 6.91 | Vietnam | 7.47 | |

| Italy | 6.91 | Russia | 7.32 | |

| Slovenia | 6.86 | Peru | 7.31 | |

| United States | 6.75 | Argentina | 7.26 | |

| Ireland | 6.74 | Baku (Azerbaijan) | 7.24 | |

| Poland | 6.74 | Philippines | 7.21 | |

| Korea | 6.52 | Bulgaria | 7.15 | |

| Japan | 6.18 | Brazil | 7.05 | |

| United Kingdom | 6.16 | Malaysia | 7.04 | |

| Turkey | 5.62 | Morocco | 6.95 | |

| Jordan | 6.88 | |||

| United Arab Emirates | 6.88 | |||

| Qatar | 6.84 | |||

| Lebanon | 6.67 | |||

| China | 6.64 | |||

| Malta | 6.56 | |||

| Chinese Taipei | 6.52 | |||

| Hong Kong (China) | 6.27 | |||

| Macao (China) | 6.07 | |||

| Brunei Darussalam | 5.80 |

As can be seen, among the OECD countries the lowest levels of satisfaction were in Turkey, the UK and Japan. The United States was also near the bottom of the list. As so often found, Finland was near the top. Among non-OECD countries, satisfaction was noticeably high in Latin America and post-Communist countries. In most countries, 15-year-old boys were on average happier than 15-year-old girls, with 72% reporting scores of 7 or above compared with only 61% for girls. In most countries, satisfaction was higher among young people from advantaged backgrounds and slightly higher for people from non-immigrant households.

Over time, between 2015 and 2018, young people became less satisfied in every country surveyed (except South Korea). This is a remarkable fact. The average fell by 0.3 points (from 7.3 to 7.0). But the fall was particularly striking in the UK (0.8 points) and in the United States, Japan and Ireland (0.6 points).

Life Expectancy and WELLBYs

Finally, we need to bring into play a completely different dimension – the length of life. As we argued in Chapter 2, the ultimate test of a society’s success is not only the wellbeing that people experience but also the number of years for which they experience it. In other words, what we care about is the number of Wellbeing-Years (or WELLBYs) per person born.Footnote 18

There is, of course, no direct and meaningful way of measuring, at a point in time, the length of people’s lives. But statisticians measure life-expectancy at a point of time as the years a person born now would live if age-specific mortality rates remained as they are now. So a natural measure of the current success of a society is given by

This is not, of course, an appropriate maximand for policy, which should also involve the future wellbeing of those alive and those not yet born. But it is an interesting measure of where we are now.

Table 6.2 provides this assessment for each region of the world for 2017/19 (before COVID-19) and also for 2006/8 (the first available date). As the table shows, average current wellbeing fell slightly between the two periods, especially in South Asia, the Middle East/North Africa and North America. But life-expectancy rose everywhere, above all in Sub-Saharan Africa where it rose by an astonishing seven years. Thus the average WELLBYs per citizen born in the world rose from 369 (5.4 × 68.7) to 373 (5.2 × 72.4). The increase was especially large in the post-Communist regions. But in South Asia, the Middle East/North Africa and in North America there was a fall in current social welfare.

Table 6.2 Trends in wellbeing, life expectancy and social welfare

| Average wellbeing per year | Life expectancy (in years) | Social welfare (WELLBYs per person) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006/8 | 2017/19 | 2006/8 | 2017/19 | 2006/8 | 2017/19 | Change | |

| World | 5.4 | 5.2 | 68.7 | 72.4 | 369 | 373 | 4 |

| N America | 7.3 | 7.0 | 78.6 | 79.5 | 576 | 556 | −21 |

| S America | 6.2 | 6.1 | 73.4 | 75.3 | 455 | 463 | 8 |

| W Europe | 6.9 | 6.8 | 80.3 | 82.2 | 550 | 561 | 11 |

| C+E Europe | 5.4 | 6.1 | 74.6 | 77.4 | 402 | 488 | 66 |

| Former Soviet Union | 5.2 | 5.4 | 67.5 | 72.2 | 352 | 393 | 41 |

| S E Asia | 5.1 | 5.4 | 69.4 | 72.5 | 354 | 391 | 37 |

| E Asia | 4.9 | 5.2 | 74.8 | 77.8 | 369 | 408 | 39 |

| S Asia | 5.1 | 4.0 | 65.7 | 69.5 | 334 | 278 | −56 |

| M E + N Africa | 5.3 | 4.9 | 71.9 | 74.6 | 380 | 364 | −16 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 4.5 | 4.5 | 53.6 | 60.7 | 240 | 271 | 31 |

Conclusions

(1) Wellbeing varies hugely in the human population. Over a sixth of the world’s population has wellbeing of 3 or below (out of 10) – a condition of serious misery. And another sixth has wellbeing of 8 or above.

(2) About 80% of this variance of wellbeing worldwide is within countries and about 20% is between countries.

(3) Between 1980 and 2007, average wellbeing rose in more countries than where it fell. But since 2008, wellbeing has fallen in roughly the same number of countries as where it has risen. Notable falls in wellbeing have been in India, the United States and the Middle East/North Africa. In the US average wellbeing is no higher than it was in the 1950s and the inequality of wellbeing is one of the highest in the OECD.

(4) In most countries, the inequality of wellbeing has increased since 2008, except in Europe, which now has lower inequality than any other region.

(5) Since 2006/8 there has been a large increase in negative affect and in stress.

(6) Average wellbeing is very similar for men and women in almost every country. It declines with age in most parts of the world but in North America and Europe it improves after mid-life. Average wellbeing is below average for most ethnic minorities in most countries.

(7) Children’s wellbeing fell substantially between 2015 and 2018 especially in the UK, the United States and Japan, countries where the wellbeing of 15-year-olds is lower than in most other OECD countries.

(8) Meanwhile, adult life-expectancy has risen in all regions of the world, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. So the Wellbeing-Years (WELLBYs) that a person now born can expect have increased since 2006–2008 in all regions of the world except South Asia, the Middle East/North Africa and North America.

The rest of Part III of this book attempts to explain some of these facts – both the level of wellbeing and its inequality in the human population. But first we have to sort out the tools we need for this purpose.

Questions for discussion

(1) Do you believe the patterns of wellbeing portrayed in this chapter?

(2) You may want to develop hypotheses about what causes these facts.

There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.

To explain the level and inequality of wellbeing, we use the standard tools of quantitative social science. These are mainly the techniques of multiple regression. In this chapter, we shall show how multiple regression can address the following issues.Footnote 1

(1) What is the effect of different factors on the level of wellbeing (using survey data)?

(2) What problems arise in estimating this and how can they be handled?

(3) How far do different factors contribute to the observed inequality of wellbeing?

(4) How can experiments and quasi-experiments show us the effect of interventions to improve wellbeing?

So suppose that a person’s wellbeing (W) is determined by a range of explanatory variables

(X1, …, XN) in an additive fashion. But in addition there is an unexplained residual (e), which is randomly distributed around an average value of zero. Then the wellbeing of the ith individual (Wi) is given by

which we can also write as

(1)

(1)In this equation, wellbeing is being explained by the Xjs. So wellbeing is the ‘dependent’ variable (or left-hand variable) and the Xjs are the ‘independent’ or (right-hand) variables. These right-hand variables can be of many forms. They can be continuous like income or the logarithm of income or like age or age squared. Or they can be binary variables like unemployment: you are either unemployed or not unemployed. These binary variables are often called dummy variables and they take the value of 1 when you are in that state (e.g., unemployed) and the value of 0 when you are not in that state (e.g., not unemployed).

If we want to explain wellbeing, we have to discover the size of the effect of each thing that affects wellbeing. In other words, we have to discover the size of the ajs. For example, suppose

From Chapter 8, you will find as benchmark numbers that a1 = 0.3 and a2 = −0.7. This means that when a person’s log Income increases by one point, her wellbeing increases by 0.3 points (out of 10). Similarly, when a person ceases to be unemployed, her wellbeing increases by 0.7 points (ignoring any effect of a simultaneous change in income). And, if both things happen together, wellbeing increases by a whole point (0.3 + 0.7).

Estimating the Effect of a Variable

But how are we to estimate, as best we can, the true values of these aj coefficients? The best unbiased way of doing this is to find the set of ajs that leaves the smallest sum of squared residuals ei2, across the whole sample of people being studied.Footnote 2 This is known as the method of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). Standard programmes like STATA will do it for you automatically. However, there are 4 possible problems with such estimates when obtained from a cross-section of the population.

Omitted variables

Suppose that equation (2) is not the correct model but that another X variable should also be in the equation. Suppose, for example, that the right model is

where Education means years of education. Clearly education and income are positively correlated. So if a1 and a3 are positive, people with higher income will be getting higher wellbeing for 2 reasons:

the direct effect of income (a1) and

the effect of education in so far as it is correlated with income.

Thus, equation (2) will give an exaggerated estimate of the direct effect (a1) of income on wellbeing.Footnote 3 To leave out education is to leave out a confounding variable. And any such confounding variable must have two properties:

it is causally related to the dependent (LHS) variable and

it is correlated with an independent (RHS) variable.

If we lack data on the confounding variable, the classic way to overcome this problem is to use time-series panel data on the same people. Provided the omitted variable is constant over time, it can cause no problem, since we can now estimate how changes in income within the same person affect changes in her wellbeing. Thus, if we use time-series data, we cease to compare different individuals at the same point of time and we compare the same individual at different periods of time. Algebraically, we do this by expanding equation (2) to include multiple time periods (t) and adding a fixed effect dummy variable (fi) for each individual. This picks up the effect of all the fixed characteristic of the individual (which for most adults will include education). Thus, we now explain the wellbeing of the ith person in the tth time period by

There are standard programmes for including fixed-effects. A similar method to this is used for analysing the effect of experiments, but we shall come to this later.

Reverse causality

However, there is another problem. Suppose we are interested in the effect of income on wellbeing. But suppose that there is also the reverse effect – of wellbeing on income.Footnote 4 How can we be sure that, when we estimate equation (2), we are really estimating the effect of income on wellbeing rather than the reverse relationship or a mixture of the two? In other words is equation (2) in principle ‘identifiable’?

For an equation to be identifiable, it must exclude at least one of the variables that appears in the second relationship (the one that determines income).Footnote 5 But, even if it is identifiable, there is still the problem of getting a causal estimate of the effects of the endogenous variable.

The aim has to be to isolate that part of the endogenous variable that is due to something exogenous to the system. A variable that can isolate that part of the endogenous variable is called an instrumental variable. For example, if tax rates or minimum wages changed over time, these would be good instruments. Instrumental variables can also be used to handle the problem of omitted variables. In every case a good instrument

(i) is well related in a causal way to the variable it instruments and

(ii) should not itself appear in the equation, (i.e., it is not correlated with the error term in the equation).

There are programmes for the use of instrumental variables (IVs).

Another way to isolate causal relationships is through the timing of effects. For example, income affects wellbeing in the next period rather than the current period. We can then identify its effect by regressing current wellbeing on income in the previous period. Similarly with unemployment. This gives us

Measurement error

Another source of biased estimates is measurement error. If the left-hand variable has high measurement error, this will not bias the estimated coefficients aj. But, if an explanatory variable Xj is measured with error, this will bias aj towards zero. If the measurement error is known, this can be used to correct for the bias. But, if not, an instrumental variable can again come to the rescue, provided it is uncorrelated with the measurement error in the variable it is instrumenting.

Mediating variables

A final issue is this. A multiple regression equation such as (3) shows us the effect of each variable upon wellbeing holding other things constant. But suppose we are interested in the total effect of changing one variable upon wellbeing. For example, we might ask What is the total effect of unemployment upon wellbeing?

The total effect is clearly

a2, plus

a1 times the effect of unemployment upon log income.

That is one way you could estimate it. An alternative way is to take equation (2) and leave income out of the equation, so that the estimated coefficient on unemployment includes any effect that unemployment has on wellbeing via its effect on income.

In a case like this, income is a mediating variable. If we are only interested in the total effect of unemployment, we can simply leave the mediating variable out of the equation. Or we can estimate a system of structural equations consisting of (2) and the equation that determines income. This discussion brings out one crucial point in wellbeing research. We should always be very clear what question we are trying to answer. We should choose our equation or equations accordingly.

Standard errors and significance

All coefficients are estimated with a margin of uncertainty. Each estimated coefficient has a ‘standard error’ (se) around the estimated value. The true value will lie within 2 ‘standard errors’ on either side of the estimated coefficients in 95% of samples. Thus the ‘95% confidence interval’ for the αj coefficient runs from ![]() , where

, where ![]() means the estimated value of αj. If this confidence interval does not include the value zero, the estimated coefficient is said to be ‘significantly different from zero at the 95% level’.

means the estimated value of αj. If this confidence interval does not include the value zero, the estimated coefficient is said to be ‘significantly different from zero at the 95% level’.

For many psychologists, this issue of significance is considered crucial. It answers the question ‘Does X affect W at all?’ But for policy purposes the more important question is ‘How much does X affect W?’ So the coefficient itself is more interesting than its significance level. For any sample size, the estimated coefficient is the best available answer to the question of how much X changes W. And, if you increase the size of the sample, the expected value of the estimated aj does not change but its standard error automatically falls (it is inversely proportional to the square root of the sample size). So in this book we focus more heavily on the size of coefficients than on their significance (though we sometimes show standard errors in brackets in the tables).

The question we have been asking thus far in this chapter is How does wellbeing change when an independent variable changes? In algebraic terms, we have been studying dW/dXj? This is the type of number we need in order to evaluate a policy change. For example, suppose we increased the income of poor people by 20%, how much would their wellbeing change (on a scale of 0–10)? If aj = 0.3, it would increase by 0.06 points (0.3 × 0.2). A quite different question is In which areas of life should we look hardest in the search for better policies?

The Explanatory Power of a Variable

If our main aim is to help the people with the lowest wellbeing (as we discussed in Chapter 2), then our focus should be on what explains the inequality of wellbeing. To see why, suppose first that wellbeing depends only on one variable X1, with W = α0 + α1X1. Then the distribution of W depends only on the distribution of X1. If W is unequal, it is because X1 is unequal and α1 is high. The higher the standard deviation (σ1) of X1 and the higher α1, the greater the inequality of W. This is illustrated in Figure 7.1. For high variance of W, the numbers in misery correspond to the areas A and B. But for the low variance of W the numbers in misery correspond only to the area B.

Figure 7.1 How the numbers in misery are affected by a1σ1

A next natural step is to compare the standard deviation of a1σ1 with the standard deviation of wellbeing itself. Obviously, if they were equal in size, the spread of X1 would be ‘explaining’ the whole spread of wellbeing σw – in other words, the two variables would be perfectly correlated. The correlation coefficient (r) between W and X1 is therefore a1σ1/σw:

However, this can be either positive or negative depending on the sign of a1. So a natural measure of the explanatory power of a right-hand variable is the squared value of r (which is also often written as R2):

Since the denominator is the variance of wellbeing, this shows what proportion of the variance in wellbeing is explained by the variance of X1.

In the real world, wellbeing depends on more than one variable (see equation [1]). The policy-maker may then ask Which of these variables is producing the largest amount of misery?Footnote 6 For this purpose, we need to compare the explanatory power of the different variable. This is done by computing for each variable its partial correlation coefficient with wellbeing. This partial correlation coefficient is normally described as βj where

This β-coefficient will appear frequently throughout this book.Footnote 7

These β-coefficients are hugely interesting, as we shall see via two steps. First, starting from equation (1) we can readily derive the following equation.Footnote 8

(6)

(6)Here we have standardised each variable by measuring it from its mean and dividing it by its standard deviation. These standardised equations appear many times in this book.Footnote 9

But, to see the importance of these βs, we move on to a second equation, which is derived from (6).Footnote 10 This says

r2 is the proportion of the variance of W that is explained by the right-hand variables. And rgk is the correlation coefficient between Xg and Xk.

Thus, the left-hand side is the share of the variance of wellbeing that is explained. The right-hand side consists of Σβj2, which includes all the effects of the independent variation of the Xjs, plus the effects of all their covariances. Thus βj (or the partial correlation coefficient) measures the explanatory power of a variable (just as the correlation coefficient does in a simple bivariate relationship).

But some readers may wonder if this approach can handle independent variables that are binary. It can, because the standard deviation of a binary variable is simply ![]() , where p is the proportion of people answering Yes to the binary question. For example, the standard deviation of Unemployed is

, where p is the proportion of people answering Yes to the binary question. For example, the standard deviation of Unemployed is ![]() where u is the unemployed rate. Thus, if Xj is Unemployed, its β coefficient is

where u is the unemployed rate. Thus, if Xj is Unemployed, its β coefficient is![]() .

.

Binary dependent variables

The matter is more complicated when it is the dependent variable that is binary. For example, suppose we divide the population into those who are in misery (with wellbeing below say 6) and the rest. How can we handle this? The most natural approach is, as normal, to regress the binary variable on all the other variables. This is what we often do in this book and, since it provides statistics of the standard kind, it is easy to understand.Footnote 11

Box 7.1 Odds ratios

In analysing the effect of one binary variable on another binary variable, psychologists and sociologists often use the concept of an ‘odds ratio’ rather than the values of aj and βj we have been discussing. Suppose, for example, we ask: How much more likely are unemployed people to be in misery, compared with people who are not unemployed? Imagine 100 people were distributed as follows (Table 7.1):

Table 7.1 Distribution of 100 people by unemployment status and misery status

| In misery | Not in misery | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed | 2 | 8 | 10 |

| Not unemployed | 9 | 81 | 90 |

| Total | 11 | 89 | 100 |

In this situation, the chance of an unemployed person being in misery is much higher than the chance of a non-unemployed person being in misery. The odds-ratio is

But odds ratios do not answer either of the main questions we are addressing in this chapter. First, if we are interested in the effect on wellbeing of reducing unemployment, the proper measure of this effect is not the odds ratio but the absolute difference in the probabilities of misery between unemployed and non-unemployed people, that is, 0.2−0.1 = 0.1. Second, if we are interested in the power of unemployment to explain the prevalence of misery, the correct statistic is the correlation coefficient between the two. So we shall not be showing odds ratios in this book, though the reader is able to compute them, given the necessary information.

Effect size of a binary independent variable

We have so far considered two ways in which to report regression results. One is to report the absolute effect of say unemployment on wellbeing in units of wellbeing. The other is to look at the relationship when both variables are standardised. However, there is the third approach that is often useful. This is to measure only the dependent variable in a standardised fashion. For example, we might ask ‘When a person becomes unemployed, by how many standard deviations does his wellbeing go down?’ This is a measure known as the effect size of the independent variable (sometimes knows as Cohen’s d):

This is particularly useful when reporting the effect of an experiment.Footnote 12

Experiments

So far, we have been discussing the use of naturalistic data – mainly obtained by surveys of the population. As we have mentioned, it is often difficult to establish the causal effect of one variable on another from this type of data. The simplest way to establish a causal relationship is through a properly controlled experiment. Moreover, if you want to examine the effect of a policy that has never been tried before, it is the best way to get convincing evidence of its effects.

So how do we estimate the effects of being ‘treated’ in an experiment? Let’s begin with a simple example. Suppose we want to try introducing a wellbeing curriculum into a school. Our aim is to see whether it makes any difference to those who receive it. So we would select two groups of pupils who were as similar to each other as possible. Then we would give the wellbeing curriculum to the treatment group (T) but not the control group (c). We would also measure the wellbeing of both groups before and after the treatment. So we would have the following values of wellbeing for each of four situations (Table 7.2).

Table 7.2 Average wellbeing of each group before and after the experiment

| Before | After | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment group (T) | WT0 | WT1 |

| Control group (C) | WC0 | WC1 |

To find the average effect of the treatment, we would compare the change in wellbeing experienced by the treatment group (T) with that experienced by the control group (C). Thus, the ‘average treatment effect on the treated’ (ATT) would be estimated as

In other words, the ATT is the ‘difference in differences’, or for short the ‘diff in diff’.

There may of course be many ways in which both groups changed between periods 0 and 1 – they will become older, they may experience a flu epidemic or whatever. But those changes should be similar for both groups. Thus the only observable thing that can produce a different change in wellbeing is the fact that Group T took the course and Group C did not.

Of course, there may also be some unobservable difference in experience, which means that the ATT is always estimated with a standard error. So, to put things into a more general form, let’s imagine we have observations over a number of years. We then estimate

Here Tit is a variable which takes the value 1 in all periods after someone has taken the course, vt is a year dummy, fi is a person fixed effect and eit is random noise.

So far, we have assumed that in our experiment we can easily arrange for the treatment group and the control group to be reasonably similar. This is never in fact completely possible. But the method that gets us closest to it is ‘random assignment’.Footnote 13 In this case, we select an overall group for the experiment and then randomly assign people to either Group T or Group C (e.g., by tossing a coin for each individual). In this way, the groups are more likely to be similar than in any other way. Of course we can then check whether they differ in observable characteristics (X) and we can then allow in our equation for the possibility that these variables affect the measured ATT. Our equation then becomes

Estimating equations like this are quite common.

However, randomisation between individuals is often not practicable. For example, suppose you wanted to test whether higher income transfers raised wellbeing enough to justify the cost. You could not randomly allocate money within a given population – it would be considered unfair since the transfer clearly benefits the recipient. You might, however, choose to transfer money to all eligible people in some areas and not in others, with the allocation between areas being random. This might not be considered unfair. Similarly, suppose you wanted to test the effects of improved teaching of life-skills in schools. Within a school it might be organisationally impossible to give improved teaching to some children and not others – or even to some classes. But you could use random assignment across schools. Or you could even argue that it is ‘quasi-random’ whether a child is born in Year t or Year t − 1; in this case, you could use children born in year t as a control group in the trial of a treatment applied to those born in year t + 1 (see Chapter 9). So all experiments should, if at all possible, use randomisation to reduce the unobservable differences between the treatment and control groups.

Selection bias

But suppose an innovation is made without an experiment and we then want to know its effects. For example, an exercise programme has been established, which some people have decided to adopt. Has it done them any good?

The only information that we have is for the period after the innovation. But we do also have information on people who did not opt in to the programme. So, can we answer our question by comparing the wellbeing of those who took the programme with those who didn’t? Probably not, because the people who opted into the programme may have differed from those who didn’t: they may well have started with higher wellbeing in the first place. So, if we just compared their final wellbeing with those of non-participants, the difference could be largely due to ‘selection bias’.

One method to deal with this is called Propensity Score Matching. In it we first take the whole sample of participants and non-participants and do a logit (or probit) analysis to identify that equation that best predicts whether they participate or not. From this analysis, we can say for every participant what was the probability they participated. We then find, for each participant, a non-participant with the same (or nearly the same) probability of participating. It is those non-participants who become the control group and we now compare their wellbeing with that of the treatment group. This gives us our estimate of the average treatment effect on the treated:

Summary

(1) If W = a0 + ∑aj Xj +e, then the best unbiased way to estimate the values of the ajs is by Ordinary Last Squares (choosing the ajs to minimise the sum of squared residuals e2).

(2) Omitted variables are confounders that can lead to biased estimates of the effect of the variables which are included.

(3) Time series estimation can eliminate any problem caused by omitted variables which are constant over time. Time series can also help to identify a causal effect if this takes place with a lag, so that for example Xt-1 is affecting Wt.

(4) If a right-hand variable is endogenous, it should if possible be instrumented by an instrumental variable that is independent of the error in the equation. Instrumental variables can also help with omitted variables and measurement error.

(5) If an explanatory variable is measured with error, its estimated coefficient will be biased towards zero. This problem can again be solved by using an instrumental variable uncorrelated with the original measurement error.

(6) All regression estimates are estimated with ‘standard errors’ (se). The 95% confidence interval is the coefficient ± 2 se. Provided this interval does not include zero, the coefficient is ‘significantly different from zero at the 95% level’. But the coefficient estimate is more interesting that its significance.

(7) To find the explanatory power of the different variables, we run the equation using standardised variables, that is, the original variables minus their mean and divided by their standard deviation. The resulting coefficients (βj) – or partial correlation coefficients – reflect the explanatory power of the independent variation of each variable Xj. They are equal to ajσj/σw where w is the dependent variable.

(8) The surest way to determine a causal effect is by experiment. The best form of experiment is by random assignment. We then measure the wellbeing of the treatment and the control group before and after the experiment. This difference-in-difference measures the average treatment effect on the treated.

(9) Where random assignment is impossible, naturalistic data can be used and the outcome for the treatment group compared with a similar untreated group chosen by Propensity Score Matching.

(10) If the measured effect of a treatment is a (in units of the outcome variable W), the ‘effect size’ is a/σw.

We can now put these tools to work.

Happy the man who has learned the cause of things …

We can now put these tools to use in explaining the huge inequalities that exist in wellbeing. These inequalities are interesting in themselves. And they also provide naturalistic evidence that helps us to predict how policies of different kinds would change people’s wellbeing.Footnote 1 So this chapter applies the tools presented in Chapter 7 to explain and learn from the differences in Chapter 6.

We proceed as follows:

First, we outline a framework for how adult wellbeing is determined within a country.

Next, we take adult wellbeing differences within a country and see how these are explained by differences in adult characteristics.

Then we go back to childhood and see how well the child predicts the adult.

Finally, we look at the role of social norms and institutions and study their effects by looking at differences between countries.

This chapter is very important in setting the framework for the rest of Part III of the book – which looks at each influence in much more detail.

Wellbeing and the Life Cycle

Our adult wellbeing is the product of our whole life to date (see Figure 8.1). Our early development is affected first by our parents (including their genes) and then by our schooling. These are the main factors that determine our outcomes up to the end of childhood. These outcomes then help to predict our adult outcomes, which in turn determine our adult life satisfaction. In what follows, we shall work backwards, looking first at the role of adult outcomes, then at the role of child outcomes and finally (in Chapter 9) at the role of family and schooling.

Figure 8.1 How adult wellbeing is determined

Note: Earlier factors also influence later outcomes directly

Personal Determinants of Adult Wellbeing

There have been thousands of studies of the personal causes of adult wellbeing. But they are difficult to compare because they use different measures of wellbeing and they study the effect of different sets of determinants. We shall therefore focus in this chapter on one study that used a single measure of wellbeing (life satisfaction) and looked at all the main influences simultaneously.Footnote 2 The main influences included were:

Physical health (number of illnesses)

Mental health (has ever been diagnosed with depression or an anxiety disorder)

Is unemployed (versus employed)

Quality of work (index)

Family

Has partner (versus single)

Is separated (versus single)

Is widowed (versus single)

Education (years)

Many studies of wellbeing do not include mental health as an explanatory factor, since it is itself a feeling. But this is why we do not include self-reported feelings as measures of mental health – instead, we include an objective diagnosis by a third party. The question used is ‘Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse of other health professional that you had an anxiety disorder and/or depressive disorder?’ Since most such experiences are prior to being surveyed, they are essentially measuring something exogenous. Besides, it would be quite wrong not to include mental illness as an explanation for wellbeing, when this is such an important issue for so many people, independently of the other right-hand variables. As the equations that follow show, low wellbeing is not the same as mental illness and can be caused by many other factors besides mental illness.

So the task is to estimate equation (1) in Chapter 7, with current life satisfaction as the dependent variable and the variables listed above as the independent variables. The equation estimated is cross-sectional – a point to which we shall return. The study covered Britain, Germany, Australia and the United States, with broadly similar results from all four countries. The results we report in Table 8.1 come mainly from a British survey (Understanding Society). But the mental health coefficient is from the United States and Australia (where the measure of mental health is more exogenous and the results are very similar). And the quality of work result comes from a different study using the European Social Survey.Footnote 3

Table 8.1 How different factors affect life satisfaction (0–10) of adults over 25 (Britain) (Pooled cross section) (R2 = 0.19)

| Effect on life satisfaction (0–10) | |

|---|---|

| Physical health problems (No. of illnesses) | −0.22 (0.01) |

| Mental health problems (0,1) | −0.72 (0.05) |

| Unemployed (versus employed; 0,1) | −0.70 (0.04) |

| Quality of work (effect of 1SD) | +0.40 (0.04) |

| Partnered (versus single; 0,1) | +0.59 (0.03) |

| Separated (versus single; 0,1) | −0.15 (0.04) |

| Widowed (versus single; 0,1) | +0.11 (0.08) |

| Income (log) | +0.17 (0.01) |

| Education (years) | +0.03 (0.00) |

Notes: Control variables include comparators’ income, education, unemployment and partnership, as well as gender, age and age squared and year fixed effects. Standard errors in brackets.

Table 8.1 shows, for example, that people ever diagnosed with mental illness are currently (other things equal) less satisfied with their life by 0.72 points.Footnote 4 Unemployment has a similar effect, as does not having a partner. A unit increase in log income increases wellbeing by 0.17 points, which means that the doubling of income raises wellbeing by 0.12 points.Footnote 5 Note that the standard error (in brackets) of these coefficients are small relative to the coefficients themselves, so the estimates are fairly well defined and significantly different from zero at the 95% level.

From Table 8.1, we learn the effect of each variable upon wellbeing. But this does not tell us how far the inequality of that variable explains the inequality of wellbeing. For that purpose, we have to multiply the effect of each explanatory variable by its own standard deviation – and then divide it by the standard deviation of wellbeing. This gives us the βj measure discussed in Chapter 7 – recall that βj = ajσj/σw.

In Figure 8.2, we give these β values in graphical form. To simplify the display, we have treated every variable as if it had a positive β – by, for example, relabelling Unemployed as Not unemployed.

Figure 8.2 What explains the variation of life satisfaction among adults over 25? (Britain) Partial correlation coefficients (β) (R2 = 0.19).

Notes: For quality of work see their chapter 4. Standard errors in brackets

Notice first that the whole equation has an R2 of 0.19 – we are only explaining 19% of the total variance. It is very important not to over-claim explanatory power.Footnote 6 And it is also quite wrong to label the unexplained residual as ‘luck’. It is quite simply the variation in wellbeing that we have not been able to explain or is due to measurement error. Nevertheless, what we do know is that health is extremely important (especially mental health). Work is also important – having it (if you want it) and its quality. Family life also matters.

So does income, but its explanatory power is no higher than many other variables. In Figure 8.2 it explains under 1% of the variance of life satisfaction, since its β2 value is under 0.12. But as we shall see in Chapter 13, the figure can rise to 3% in some countries – but still no higher than some other influences.

Before we accept this conclusion, we have to ask some of the questions we discussed in Chapter 7. First, is there a problem of measurement error? This is unlikely to affect the ranking of income in Figure 8.2 since income is measured more accurately than many of the other variables. Second, are there important omitted variables or problems of endogeneity? To investigate these problems, we can use the panel data to perform a fixed-effects analysis as in Equation (7.4). In panel regressions, all the coefficients are reduced, partly because the problem of measurement error becomes more acute. The coefficients on income fall more than most, though this may be partly because the exact timings are not well caught by the data. For this chapter, we stick to cross-sectional results; but in Chapter 13 we also give the results of fixed effects regressions.

It is important to stress that for all the variables in Table 8.1 and Figure 8.2, the coefficients reflect the effect of the variable, other things constant. If we wanted to investigate the total effect of income on wellbeing, we would also have to include its effects through other ‘mediating’ variables like having a partner. This is quite difficult to compute. But it is easy to compute a maximum value for the total coefficient on income (or any other variable). It is the simple bivariate coefficient, which in this case is about double the coefficient holding other things constant.

Another obvious question is this: Doesn’t income explain more of the prevalence of low wellbeing than is implied by Figure 8.2? To investigate this, we construct a new variable. This is a simple binary variable for misery (M), which is constructed as follows:Footnote 7

M equals 1 if wellbeing is 5 or below

M equals 0 if wellbeing is above 5

Misery (thus defined) affects the bottom 10% or so of the British population – so it is a good measure of deprivation. We can then run the following simple equation:

If we take averages across all individuals, this equation predicts the proportion of people in misery, which is given by

In an analysis for Britain, Australia and the United States, mental health problems accounted for more of the misery than any other factor.Footnote 8 In Britain and Australia, this was followed by physical illness, and in the United States by low income. Unemployment, though devastating to those affected, came in lower than health and poverty, because of the smaller numbers affected.

A slightly different question is What best explains who is in misery and who is not? In other words, what are the most important elements in the following relationship:

In Figure 8.3, we show the values of the β coefficients where this time Misery is the dependent variable. As can be seen, these coefficients are slightly smaller than when we are explaining the full continuous range of Life–Satisfaction (in Figure 8.2). This is to be expected. But, strikingly, the relative importance of the different factors is the same whether we are explaining low wellbeing or the whole spread across the spectrum.

Figure 8.3 What explains the variation of misery among adults over 25? (Britain) Partial correlation coefficients (β) (R2 = 0.14)

Note: See Figure 8.2

Childhood Predictors of Individual Wellbeing

So much for the adult causes of adult wellbeing. But aren’t many of the adult influences we have looked at caused by how we were in childhood? They are indeed. There are three main dimensions of child development: intellectual, emotional and behavioural. A big question for schools is ‘Which of these is the best predictor of whether a child will have a satisfying adult life?’

The following analysis is based on a follow-up of all British children born in a week in 1970 (the British Cohort Study 1970). The measures of child development that we use are these:

Intellectual: highest qualification ever obtained

Behavioural: behaviour measured at age 16 (by 17 questions asked to the mother)

Emotional: emotional health measured at age 16 (by 22 questions asked to the young person and 8 to the mother).

As Figure 8.4 shows, the best predictor of a satisfying adult life is not your qualifications but a simple measure of your emotional health at 16. This is an important finding for educational policy since, as Chapter 9 shows, schools have such a huge influence on the wellbeing of their children. Qualifications also matter of course and are by far the best predictor of an adult’s income. But, as we have seen, income is less important for adults than their mental health, which is best predicted by their emotional health in childhood.

Figure 8.4 How adult life satisfaction is predicted by child outcomes (Britain) Partial correlation coefficients (β) (R2 = 0.035)

Note: Adult life satisfaction is average at ages 34 and 42. Controls include family variables. Standard errors in brackets

As we argue in Chapter 9, child wellbeing is important in itself – childhood is a substantial part of our whole life experience. But wellbeing as a child is also the foundation for wellbeing as an adult.

The Effects of Social Norms and Institutions

We have focused so far on what explains the differences in wellbeing between people within the same country. But what explains the differences between countries? There are important social norms and institutions that everyone in a country shares. While we cannot identify these effects by studying people in one country only, we can do it by comparing one country with another. The Gallup World Poll data enable us to do just that – to study the effect of

ethical standards (trustworthiness and generosity),

networks of social support and

personal freedom.

We measure these by the answers in each country to the following questions:

| Trust | Proportion who say Yes to the first half of ‘In general, do you think that most people can be trusted, or alternatively that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?’ |

| Generosity | Proportion who say Yes to ‘Have you donated money to a charity in the present month?’ |

| Social Support | Proportion who say Yes to ‘If you were in trouble, do you have relatives or friends you can count on to help you whenever you need them?’ |

| Freedom | Proportion who say Yes to ‘Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your freedom to choose what you do with your life?’. |

We also include the effect of average GDP per head and healthy life expectancy (measured in years).

In the cross-sectional analysis in Table 8.2, we show for each of these variables how average life-evaluation changes when the percentage who say Yes rises from 0 to 100. All four factors have substantial effect. So does healthy life-expectancy – for example, an increase of 10 years raises life evaluation by 0.3 points. And the effect of income across countries is similar to its effect within many countries – a doubling of income raises average life-evaluation by 0.23 points (out of 10).

Table 8.2 How national life satisfaction (0–10) is affected by country-level variables (R2 = 0.77)

| Change | Effect on average life satisfaction (0–10) | |

|---|---|---|

| Trust | 100% v. 0% | 1.08 (.45) |

| Generosity | 100% v. 0% | 0.54 (.41) |

| Social support | 100% v. 0% | 2.03 (.61) |

| Freedom | 100% v. 0% | 1.41 (.49) |

| Income | Doubling | 0.23 (.06) |

| Health | Years of healthy life | 0.03 (.01) |

It is also interesting to see how far the different factors contribute to the actual dispersion of life satisfaction across countries. Here income plays a more conspicuous role due to the huge income differences between countries. Health differences also come through as very important. This can be seen in Figure 8.5, which gives the βj coefficients corresponding to the aj coefficients in Table 8.2. The social norms are also very important. For example, what distinguishes the eight countries with the highest life satisfaction in the world is not their income but their high levels of trust, social support, freedom and generosity.Footnote 9 These are the five Nordic countries as well as the Netherlands, Switzerland and New Zealand (see Table 13.1). The countries at the bottom are mainly the war-torn countries of sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East (Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen), which not only have poor income and healthcare but are low on the social features that wellbeing requires.Footnote 10

Figure 8.5 How differences in national life satisfaction are explained by country-level variables – partial correlation coefficients (β) (R2 = 0.77)

Conclusions

This concludes our brief initial overview of the main causes of high and low wellbeing – and of the huge variation in wellbeing in the world. All the findings are cross-sectional, with time series and experiments left to later chapters. The findings of this chapter provide the framework for the rest of Part III of the book – starting with personal factors and working outwards to those relating to whole communities.

Within a country (if it is advanced), the main factors explaining the variance of wellbeing (and the prevalence of misery) are in rough order of importance:

mental illness,

physical illness,

having work and the quality of that work,

having a partner,

family income and

education

The variation of wellbeing across countries is largely explained (in rough order of importance) by:

income,

health,

social support,

personal freedom,

trusting social relations and

generosity

Predicting whether a child will become a happy adult is not easy. But the child’s wellbeing is a better predictor of satisfaction in adult life than the child’s academic success is. And as Chapter 9 shows, both schools and parents have big effects on children’s wellbeing.

Questions for discussion

(1) Are the findings about income in Figure 8.2 credible? Could problems of measurement error have produced incorrect rankings?

(2) Is Figure 8.5 informative?

Don’t be too hard on parents. You may find yourself in their place.

We begin our lives in families. After a while we go to school. And eventually most of us form families of our own. How do these experiences affect us?

The Effect of Parents

How our parents treat us makes a huge difference. For humans, we cannot prove this experimentally, but we can for animals – by allocating them randomly to be brought up by different parents. A classic study of rats by Michael Meaney took the offspring of mother rats who were bad at licking their offspring and allocated some of them to foster mothers who were good at licking.Footnote 1 These offspring grew up to be much less stressed, and they also became much better at licking their own offspring. Similarly, a classic study of rhesus monkeys by Stephen Suomi took the offspring of overactive mothers and randomly allocated some of them to calmer foster mothers.Footnote 2 These offspring became much calmer than those who stayed with their biological mothers.

However, we cannot do such experiments on humans. So we have to rely on data thrown up by people’s actual experiences of life. Fortunately, there are now a number of longitudinal studies, which follow the same person from the cradle into adult life, and most of our understanding of the impact of families and schooling comes from these surveys. In each of them, the wellbeing of the children is measured initially by questions to their parents and teachers and then (after about 10) to the children themselves as well. Here are some key findings.

Every child needs unconditional love. The basic need is for a secure emotional tie to at least one specific person. This experience of ‘attachment’ is the basis for an inner security that can last throughout life.Footnote 3 Sixty years ago, the importance of attachment was identified by John Bowlby;Footnote 4 and his idea has stood the test of time quite well. In meta-analyses, early attachment is correlated with later social competence (r = .18), pro-social behaviour (r = .15) and inner wellbeing (r = .08),Footnote 5 and these correlations are undoubtedly underestimates because attachment is so difficult to measure precisely.

A striking illustration of the importance of caring relationships comes from a tragic ‘natural experiment’. After the end of Communism, some Romanian orphans were randomly assigned to foster-care in Western families; the unlucky ones remained in the orphanage. On average, the children were 21 months old when they were assigned one way or the other, and they were assessed again at 4 ½ years of age. If they had been assigned for foster-care, the children’s mental and cognitive wellbeing at 4 ½ was over one half of a standard deviation higher than if they had stayed in the orphanage.Footnote 6 And the younger the age at which the fostering began the better the outcome.

So the love of caregivers is essential. But so too is firmness – the ability to set boundaries. If combined with warmth, this is known as ‘authoritative’ parenting, and it is the most widely recommended approach. In this approach, compliance with rules does not come from fear, but children learn to internalise the parent’s response and thereafter act to please their own ‘better selves’.Footnote 7

Abusive parents can change their children for life, and abuse includes psychological neglect as well as sexual or physical abuse. Though most abused children develop normally, a minority experience long-lasting damage. On average, there are marked brain differences between people who have and who have not been maltreated as children.Footnote 8 Maltreatment also affects behaviour,Footnote 9 but the long-term effects on internal wellbeing are even stronger.Footnote 10

So for a child the relationship to her parents is crucial. But so is the relationship between the parents themselves. At present, 50% of 16-year-olds are in separated families in the United States, and in Britain it is over 40%. How much does this matter?

The literature on child development is large.Footnote 11 However, most of the main findings can be illustrated from within one study, which makes the findings on different influences easier to compare. This is the famous ALSPAC survey of all the children born in or around Bristol, England in 1991/2. Table 9.1 shows how their parents affected the wellbeing of their children – and also their behaviour and their academic performance (all measured at age 16).

Table 9.1 How child outcomes at age 16 are affected by family and schooling – partial correlation coefficients (β)

| Wellbeing at 16 | Behaviour at 16 | Academic score at 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conflict between parents | −0.04 | −0.14 | −0.02 |

| Mother’s mental health | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| Father’s mental health | 0.04 | – | – |

| Family income (log) | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.14 |

| Mother’s involvement with child | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Mother worked (% of 1st year) | – | – | −0.02 |

| Mother worked (% of other years) | – | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Father unemployed (% of years) | – | – | −0.03 |

| Parents’ education (years) | – | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Mother’s aggression to child | −0.03 | −0.12 | – |

| All parental variables | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

Note: Wellbeing is the average of mother’s and child’s replies to the Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. Behaviour is mother’s replies to Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire. Academic score is the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE). Control variables include gender, ethnicity and the name of the primary and secondary school. For questionnaires see Annex 9.1.

As the table shows, family conflict is bad for all three of these outcomes. And, incidentally, for any given level of family conflict, a break-up of the family causes no additional damage, except to academic performance. But ongoing conflict between the parents after they break up increases the risk that the children will become depressed or aggressive. By contrast, seeing more of the absent parent reduces that risk.Footnote 12

Closely related to family conflict is the mental health of the parents. In the Bristol study, the single most important family variable predicting a child’s wellbeing at 16 was the mental health of the mother.Footnote 13 The father’s mental health also mattered but less so – probably because the mother is still, generally, the primary care giver. Clearly poor mental health can lead to family conflict, and vice-versa, but what emerges clearly is that both matter, holding the other constant.

There are three other causal factors that are much discussed. The first is family income. This is much less important for child wellbeing than it is for exam performance. The Bristol study showed that a 10% rise in family income would increase a child’s wellbeing by only 0.007 standard deviations. Similar findings emerge from other studies.Footnote 14 A second important influence is parental involvement in the life of the child. This is important in early life, but in the Bristol study it had few lasting effects. And the third issue is whether the mother works and for how long. In the majority of studies, this has no negative effect on child wellbeing, once the positive effect of the mother’s earnings is taken into account.Footnote 15

As the last row of Table 9.1 shows, the overall effect of all the observed parental characteristics upon the wellbeing of the child is a β-coefficient equal to 0.27.Footnote 16 It is time to compare this with the contribution of schooling.

The Effect of Schools

The Bristol study covered all the children who were born in that area over a 2-year period. As a result, each school in the area taught many children who were in the study. This enables us to see how much difference it made which school a child went to. The results showed that it made a very great difference – the schools really did affect the wellbeing of the children, as well as their behaviour and their exam performance.

The study estimated the following equation for wellbeing (W), as well as similar equations for behaviour and academic score:

Here ![]() is the wellbeing of the ith child, and the Xijs are the characteristics of the parents. There is also a 1/0 dummy variable

is the wellbeing of the ith child, and the Xijs are the characteristics of the parents. There is also a 1/0 dummy variable ![]() for each school (which takes the value 1 when the school is the one the individual attended and otherwise zero). So the coefficient as tells us what difference it made that a pupil went to school s.Footnote 17

for each school (which takes the value 1 when the school is the one the individual attended and otherwise zero). So the coefficient as tells us what difference it made that a pupil went to school s.Footnote 17

We can now ask: How far did these different effects of the different schools contribute to the overall spread of wellbeing in the child population? The answer can be found by looking at the standard deviation of the as coefficients (weighted by pupil numbers) relative to the standard deviation of W. The answers are in Table 9.2. In the first row, the table examines how much difference secondary schools make to children at age 16, holding constant not only all the measured family variables but also the child’s measurement on the same outcome when she entered the school at age 11. The second row does the same for primary schools, showing their effects at age 11 holding constant the measurement of the same outcome at age 8. And the third row shows their effects at age 8 holding constant the measurement of the same outcome at age 7. As Table 9.2 shows, schools make a remarkably huge difference to the wellbeing of their pupils – almost as much a difference as they make to their academic performance. And, looking back at Table 9.1, schools are making as much difference to child wellbeing as parents do (in so far as we can measure parents’ characteristics).

Table 9.2 Standard deviation of school dummy coefficients for different standardised outcomes

| Wellbeing | Behaviour | Academic performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary school | Age 16 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.29 |

| Primary schools | Age 11 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| Age 8 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

Note: Academic performance was measured at 16 by GCSE score; at 11 by KS2 Maths, English and Science; and at other ages by local data on Maths, Reading and Writing.

For primary schools, we can go a lot further and isolate the effect of individual teachers. This is possible because each child has only one main teacher in any one year. So we use the same methodology as shown in equation (1), but we replace individual schools by individual teachers. Table 9.3 shows the average results for the children aged 11 and aged 8 (averaged). Strikingly, the teachers have a more differential effect on the wellbeing of their children than they have on their maths score. It is also possible to follow the long-term effects that primary school teachers have on their pupils right into their 20s. It turns out that a teacher who is good at raising children’s wellbeing also makes her children nearly 4 percentage points more likely to go to university.Footnote 18 And a good teacher reduces their likelihood of becoming depressed, anti-social or alcoholic in their early twenties.This type of analysis shows clearly that schools and teachers make a big difference to the wellbeing of their children. But exactly how do they make that difference? This is a much more difficult question to answer. Some negative findings are fairly well established:

Smaller class sizes have no well-established advantages, in terms of their impact on wellbeing (or on intellectual development).Footnote 19

Larger schools have no well-established advantages in terms of wellbeing.

But we have little naturalistic evidence on what things do make a difference. There is, however, one way to discover: by experiment. There have been many outstanding experiments that tell us a lot about how we can produce happier children.

Table 9.3 Standard deviation of primary school teacher impacts on different standardized outcomes over the year

| Ages | Wellbeing | Behaviour | Maths score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 and 8 (pooled) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

Can we teach happiness?

In the earliest (and most famous) experiments, the wellbeing of the children was not measured as such, but many other important outcomes were. Most of these early experiments were conducted with young pre-school children (though there is no convincing evidence that early intervention is more cost-effective than later intervention).Footnote 20 Two well-known pre-school interventions are the Perry Pre-School project and the Abecedarian Project.Footnote 21 Perry Pre-School was a randomised trial on high-risk African-American children aged three and four. They spent two years in school for half the day, and their mothers were also visited at home each week. The children in the programme behaved better in subsequent life and were half as likely to be arrested than those in the control group. They also studied better, and a calculation of the project’s real rate of return to society was 7–10% per annum – better than the real return on equities.Footnote 22 The Abecedarian Project provided all-day play-based care for deprived children from birth to the age of 5. By age 21, the treatment group were less criminal and also earned more than the control group.Footnote 23

A less expensive project for children of school age was the Good Behaviour Game, played in schools in a deprived area of Baltimore. In the treatment group, each first-year primary class is divided into three teams, and each team is scored according to the number of times a member of the team breaks a rule. If the team has fewer than five infringements, a reward goes to all members of the team. Children who played (or did not play) the game were followed up to ages 19–21, and those in the treatment group used fewer drugs, less alcohol and less tobacco, and fewer had anti-social personality disorder.Footnote 24

However, one should be careful about generalising from individual experiments, since once in a while an intervention will, by chance, appear effective even if it is really not so. To see what can be achieved we really need a meta-analysis that summarises the results of a large number of experiments on children of school age.