To a psychologist it is self-evident that people are neither fully rational nor completely selfish, and that their tastes are anything but stable.

Individual Responsibility versus Collective Action

If social welfare is the objective – the thing that needs to be maximised – the next issue is Who is going to make that happen?

In traditional economics, a huge reliance is placed on the unfettered choices of individuals. As Adam Smith argued in the Wealth of Nations, people may be selfish; but, in order to get what they want, they do best by supplying what others need. The result of this process of voluntary exchange is an efficient situation where (on four assumptions) it would be impossible to make anyone better off without making someone else worse off. These assumptions are:

no monopoly or oligopolies,

no public goods (like roads or parks),

full information for all,

no one affects anyone else except through voluntary exchange (i.e. there are no ‘externalities’).

The classic example of a negative ‘externality’ is air pollution. The pollution just comes my way whether I agree to it or not. So an externality is something that just happens to me without my choosing it. Psychologists and sociologists will immediately realise that externalities comprise a huge fraction of everything that happens – from how we learn our values to whether we are robbed.Footnote 1 Coping with externality is essential if we want an efficient society.

There is also another problem with pure laissez faire (where individual action is unfettered). This is the issue of equity. Even if the framework is efficient, it may leave some people much less happy than others. People differ hugely in their talents, in the wealth they inherit and, most importantly, in their inner capacity to live an enjoyable life.

Thus pure laissez-faire is neither efficient (the four assumptions are not satisfied) nor is it equitable. So we need both society and the state to be active in promoting the wellbeing of the people and the prevention of misery. And for this they need wellbeing science.

There is also a further reason. People themselves differ hugely from what is assumed in traditional economics. On the one hand, they are much less good at promoting their own best interests than economists assume. And, on the other hand, they do often care a lot about the wellbeing of others. So we have to begin this book with a fundamental look at some of the basics of human behaviour.

In this chapter we shall investigate two questions.

Human Decision-Making

Clearly, people do to some extent pursue their own best interests. That is one reason why the human race has survived. People are ‘attracted’ to things that are good for survival – and feel happier when they achieve them (eating, mating etc.). And they ‘avoid’ things which are bad for their survival. This ‘approach/avoidance’ system is a basic part of human nature. But things are more complicated than that.

In 2002, the Nobel prize for economics was awarded for the first time to a psychologist. Some would say ‘About time’, since economics is based on a psychological theory about how people behave. But Daniel Kahneman’s message was different from that of the economists. As Kahneman put it, economists typically assume that people ‘are rational, selfish and their tastes do not change’.Footnote 2 After decades of research with his friend Amos Tversky, Kahneman believed otherwise.

Together they founded a new subject – called behavioural economics by some and behavioural science by others. Many others followed them, especially the economist/psychologist Richard Thaler (another Nobel laureate) and the lawyer Cass Sunstein. In their book Nudge,Footnote 3 they distinguished sharply between the people of traditional economic theory (who they called Econs) and real people (who they called Humans).

The two central issues are these: how effectively do people pursue their own wellbeing, and how do they impact on the wellbeing of others? There are at least five major ways in which humans do not maximise their own wellbeing:

Addiction and lack of self-control,

Unforeseen adaptation,

Framing,

Loss-aversion,

Unselfishness.

Addiction and self-control

People regularly decide to give up smoking, alcohol, drugs or gambling but then fail to do so. Frequently, they decide to do it next year, and when next year comes they decide to do it the following year. This is a case of ‘dynamic inconsistency’. It is inconsistent because in the first year they have planned on the basis of their preferences in the first year; but, when the second year comes, their preferences for the second year have changed. More generally, as people look forward, many of them give a very high priority to the present over all ensuing periods: they use a very high discount rate between now and next year. But they use a much lower discount rate when they compare next year with the one that follows, and so on – and this is why they plan to give up next year rather than this year. Interestingly, neuroscientists have shown that decisions between this year and next are made in more primitive parts of the brain than decisions between more distant future years.Footnote 4

Unforeseen adaptation/habituation

Another source of bad decisions is adaptation that is not foreseen. Human beings are generally pretty adaptable. They adapt to hardship – and they habituate to good experiences. In other words, the initial impact of a change on wellbeing eventually wears off, either partially or totally.Footnote 5 As we shall see in this book, people adapt (partly at least) to divorce, disability and poverty, and they also adapt to new houses, a new car, a new partner or a new child.Footnote 6

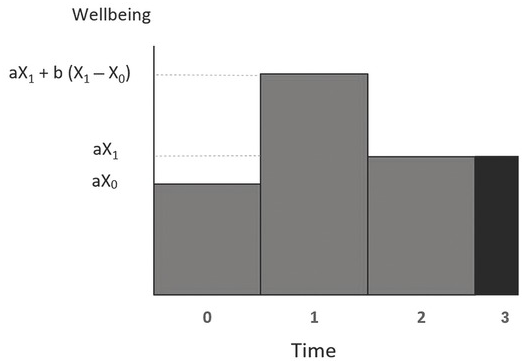

If adaptation is total, the only way to change your wellbeing permanently is to experience continual change. Thus in ‘total adaptation’ we might have

where X is anything that matters to you. So if you like X, your mood is higher when X is increasing. But, once X stops increasing, you return to your previous level of wellbeing. In other words, there is a ‘set point’ of wellbeing – neither good changes nor bad ones have any permanent effect.Footnote 7

But if in fact we follow people through their lives, we find that their wellbeing often fluctuates a lot from one decade to another.Footnote 8 So, total adaptation is relatively rare – poorer people are, for example, less happy than rich people (other things being equal). But they also suffer less than you might imagine if you thought about how you would feel next year if you suddenly became that poor.

For the most common case in real life is ‘partial adaptation’. This is very common. When you move house, your next new house makes you feel great at first, but then gradually you take it for granted (you reduce your attention to it) and you return towards how you felt before the move.Footnote 9 The same happens with a new car or a rise in income. A typical case of partial adaptation is

So suppose we start from a position where X has equalled X0 for some time, with

Then X rises to X1 and stays there from then on. In response, wellbeing in the first time period is

But in the following period, there is no further stimulating increase in X. So

This sequence is shown in the Figure 3.1, where X is taken to be desirable.Footnote 10 The key point is that the degree of adaptation is measured by the ratio of b to a. The higher b is relative to a the more adaptation occurs, and the further W moves back to its original position after its initial change. This kind of pattern applies to the effects of finding a partner, losing a partner, having children and many basic experiences.

Figure 3.1 Partial adaptation of wellbeing to changes in X

If one looks deeper into the reasons for adaptation, it clearly has much to do with attention. When you attend to things, they become very important. When you do not, they become less so. As Kahneman puts it, ‘nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you are thinking about it’. Things that are very salient and obtrusive like money can easily grab people’s attention, although for much of the time most people don’t actually think about them. For example, most people think that people in California are happier than people in the mid-west region of the United States. This is because, when they make the assessment, they are thinking about the difference in the weather. But in fact there is no difference in happiness because neither group actually spend that much time thinking about the weather.Footnote 11 Nor after a while do most people spend much time thinking about their car, unless someone draws their attention to it.

So what are the implications of adaptation for the wellbeing of the individual? The key question is whether or not individuals foresee their adaptation. If people foresee the adaptation, the decisions they take will be optimal. But in many cases, people clearly overestimate the gain in wellbeing they will eventually get from a change – a higher income, a new car, a new house or even a new partner. In such cases, people will put too much effort into acquiring the new situation, and in some cases they will come to regret the effort they made.Footnote 12 The Harvard psychologist, Daniel Gilbert, has called this a case of ‘miswanting’.Footnote 13

Framing

People’s behaviour is also hugely affected by how a decision is presented to them. Every advertiser knows this – to sell a product you associate it with something attractive, however irrelevant. And you make sure people hear about it as frequently as possible.Footnote 14 Clearly advertising affects people’s tastes. In particular it often makes them feel they need something that they did not formerly need. So, not surprisingly, there is some evidence that advertising reduces human happiness.Footnote 15

But the clearest case of framing is the effect of the ‘default’. For example, there are two ways in which people can be presented with the decision on whether to save for old age through a pension plan:

(1) you are asked if you want to opt in to the plan

(2) you are automatically enrolled unless you opt out (‘auto-enrolment’).

This can make a huge difference to what you do. For example, four US companies switched from opting in to opting out.Footnote 16 Under opting in, only 25–43% joined the company’s pension plan, but once enrolment was automatic (unless you opted out) 86–96% joined the plan. This is extraordinary. A huge decision depends simply on whether you have to push a button or not. It is clear that, on a matter as important as this, people have no clear preferences, even though most economists would assume they do. Instead, many people let the framing of the decision determine what they do.

Similar behaviour is found in relation to how you can pre-donate your organs after death. In countries where you have to opt in to donate, donation rates can be as low as 4%; but, when you have to opt out, the rates approach 100%.Footnote 17 In all these cases, opting in appears to involve a psychic cost, but this cost disappears if someone else does it for you.

Because framing is so important, anyone wanting to influence people’s behaviour must frame their approach to people carefully. This applies to government as much as to everyone else. This idea is central to the policy of Nudge, advocated by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. They argue that, if we know how we want people to behave, we should if possible, make them do so by framing their choices right, rather than by dictating to them. This approach is known as ‘libertarian paternalism’.Footnote 18

There are three key principles in framing the choices that people are offered:

(i) Keep the message simple.

(ii) If you want someone to do something, point out that lots of other people are doing it.

(iii) Associate doing it with something positive rather than something negative.

The following experiment illustrates the last point. Two randomly selected groups (A and B) were offered the following choices:

| Group A | Would you accept a gamble that offers |

| a 10% chance to win $95 and | |

| a 90% chance to lose $5 | |

| Group B | Would you pay $5 to participate in a lottery that offers |

| a 10% chance to win $100 and | |

| a 90% chance to win nothing |

The majority of Group A refused to accept the gamble, while the majority of Group B agreed to participate in the lottery. And yet both these offers were identical (just check it out). The reason for the different answers was that Group A heard the word ‘losing’ while Group B did not.

Loss-aversion and the endowment effect

This leads directly to another key human characteristic: loss-aversion. Even for small things, people hate losing them by more than they would value gaining them. This is a deep psychological trait in all animals – their strongest impulse is to hold on to what they have. Just try removing food from your cat.

Richard Thaler calls this the ‘endowment effect’. So here is a remarkably simple experiment.Footnote 19 Students are randomly divided into two groups. The first group is shown a particular type of mug and asked how much they would be willing to pay for it. The average answer is $3.50. The other group are given the same mug for free. After a while they are asked how much money they would need to be paid in order to get them to part with the mug. The average amount is $7. So the same mug is worth $7 once you have it, but you are only willing to pay half that in order to get it. Thus there is no simple answer about the value of the mug, even to the same person: it depends whether she already owns it.Footnote 20 The value depends on the ‘reference point’.

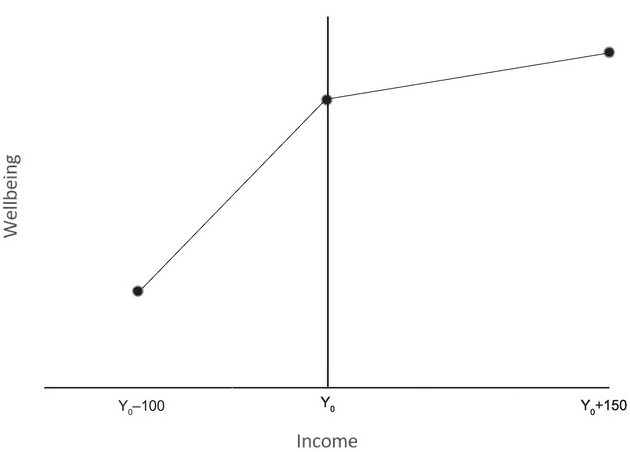

Another clear example of loss-aversion is people’s response to uncertainty, where Kahneman was awarded the Nobel prize for what he and Tversky called ‘prospect theory’. So here is one simple experiment. You are asked whether to accept the following gamble:

50% chance of winning $150 and

50% chance of losing $100.

Someone who accepts this gamble can, on average, expect to win $25. Yet the majority of people decline the offer.Footnote 21 This cannot be explained by assuming that there is a smooth relationship between happiness and income, regardless of what the person’s income was until now.Footnote 22 Instead, when people value their future income, they are comparing it with their present income. And they dislike losses more than they like gains. In other words, as Figure 3.2 shows, if a person started with an income of $yo, she would lose more happiness if she lost $100 than she would gain if she won $150.

Figure 3.2 Loss-aversion

Loss-aversion goes way beyond our attitude to income, and it affects behaviour in all sorts of ways.Footnote 23 For example, professional golfers are more likely to sink a putt if it is needed to avoid a bogey (a loss) than if the same shot would give them a birdie (a gain). Taxi drivers work longer hours on bad days, even though there is less work. Homeowners insist on selling their houses for a higher price when it involves a loss. And investors are more likely to sell stocks that have increased in value (since they were bought) than to sell stocks that have gone down: they hate to ‘realise’ losses. None of these attempts to avoid losses would be in the interest of a rational maximiser of expected outcomes.Footnote 24

Many studies have attempted to measure the scale of loss-aversion, as measured by the slope of the wellbeing/income relationship for losses relative to that for gains. The typical finding is a ratio of 2:1. For example, suppose there was

a 50% chance of winning $x and

a 50% chance of losing $100

and you were asked what value of x would make you just willing to undertake the gamble. The typical answer is $200.Footnote 25

A similar size of effect can be found at the level of the whole economy – this time in relation to actual wellbeing experienced rather than anticipated wellbeing. When incomes fall in a slump, the fall in national happiness is double the increase in happiness that occurs when incomes rise in a boom.Footnote 26 Once again the ratio is 2:1. Loss-aversion explains many forms of behaviour that standard economics cannot explain but that wise people have always noticed. One of these is wage stickiness in the downward direction. As Keynes pointed out, people fiercely resist a cut in the money value of their wage. If prices are falling enough, this may appear irrational since a person might gain in real income even though their money wage fell. But people do not see it that way, and a combination of loss-aversion and ‘money illusion’ stops wages falling and exacerbates the slump. This simple observation is central to Keynesian economics, but it is inconsistent with pure rationality.

More generally, it is loss-aversion that makes many economic reforms so difficult to achieve. Even if 95% of the population would gain, a reform will often be defeated because of the 5% who lose. Examples abound in every country. In Britain in the 1930s, mass unemployment caused little political protest until the government reformed the unemployment benefit system in a way that benefitted most unemployed people but hurt a few.Footnote 27

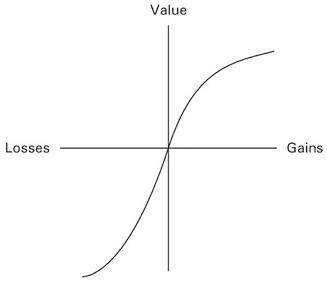

Before leaving loss-aversion, let’s note one further fact: diminished sensitivity. One aspect of this is standard in economics – as you gain more and more, you value each additional gain less and less. But the same is true of losses – as you lose more and more, each extra loss causes less and less additional pain. For example, suppose once again that we look at gains and losses of money. The corresponding changes in wellbeing are shown in Figure 3.3.

This has remarkable results. Suppose people have to choose between the following alternatives:

a 50% chance of losing $100

the certainty of losing $50.

They will prefer the gamble since it offers at least a 50% chance of losing nothing. To retain the hope of avoiding loss, decision-makers worldwide are prone to risk a lot, even though it might be more rational to accept a much smaller loss and move on.Footnote 28

Figure 3.3 Loss aversion with diminished sensitivity

The combination of loss-aversion and diminished sensitivity constitute what Kahneman and Tversky called ‘prospect theory’ and it was for this that Kahneman won the Nobel prize (Tversky having sadly died). Each prize-winner receives a personalised drawing, and the drawing on Kahneman’s certificate was a more artistic version of Figure 3.3.

Unselfishness

Finally, there is a key aspect of human behaviour that does not often appear in standard economics: unselfishness. People regularly do things for other people whom they will never see again and who could never return the favour. They return lost wallets to their owners and they are more likely to return wallets the more money they contain.Footnote 29 People give money in secret to charity; they dive into rivers to rescue drowning strangers. This behaviour can only be explained by the presence of a moral sense, partly learned and partly in our genes.Footnote 30 People of course vary in the strength of their moral sense. So what can account for this dual aspect of our human nature – the mixture of the selfish and the unselfish? You might think that at the individual level people who were more selfish would end up doing better in the Darwinian struggle for survival. And, if so, the genes for unselfishness would become less and less common. But this doesn’t happen. Two things sustain the prevalence of cooperation.

The first is social sanctions. Your fellow citizens know that for many purposes co-operation is more efficient than competition. So they punish people who won’t co-operate – such people get left out; people will not work with them. So, as the evidence shows, non-co-operators do worse on average than other humans.Footnote 31 The same happens among chimpanzees. In an impressive recent experiment with chimpanzees, there were five times more co-operative acts than non-co-operative ones – and the non-co-operators were either shunned or physically punished.Footnote 32 So one reason why people co-operate is to win the favour of others.

But there is a second reason: on average, pro-social behaviour makes us feel good inside ourselves – the ‘warm glow’. In one experiment, students were randomly divided into two groups. One group were given money to spend on themselves, and the second group were given money to spend on other people. When asked about their happiness after the experiment, those who had given the money away were happier. This experiment has been repeated in four countries and a similar experiment with toddlers has produced the same results – they smile more.Footnote 33

Neuroscience confirms this mechanism. When playing the Prisoner’s Dilemma game (when you can either ‘co-operate’ or not), people who co-operated showed more activity in the standard brain area where other positive rewards are processed.Footnote 34 And this was even before they knew whether the other player would co-operate. In other words, if you want to feel good, do good.

Externalities

The conclusion so far is that Humans do not always maximise their own wellbeing. In cases where this produces a bad outcome, good advice, nudges and even government intervention might help them do better.Footnote 35 But there is another reason for government intervention that also arises from human nature: the role of externality. Let us look briefly at three forms of externality: the trustworthiness of others, the sources of our social norms and social comparisons.

The trustworthiness of others

We are hugely affected by the ethical character of those around us (see Figure 2.1). A libertarian might argue that we can choose who to have around us. But this is not quite right. Only some people can choose. If they choose the most trustworthy, the rest of the population end up interacting with the less trustworthy. What matters for the population as a whole is the total pool of characters they can interact with. So the virtues and vices of our fellow citizens are huge external influences on our wellbeing. This has always been given as one reason for public education.

The sources of our social norms

Our own tastes and norms are things we absorb from the outside world – mostly in childhood and adolescence. They affect what we enjoy – and how we treat others. Libertarians like the Nobel prize-winning economists Gary Becker and George Stiglitz argue that no one set of tastes is better than any other (in Latin, ‘de gustibus non disputandum est’).Footnote 36 Wellbeing science offers a different view on this. As we have seen, our preferences have huge effects on other people. Our genes certainly have some effect on our tastes and norms of behaviour. But we are also hugely affected by our own parents, our schools, our peers and society as a whole. One has only to think about how tastes in fashion or music change from decade to decade or our attitudes to gender, race and smoking.

Basic human needs may not change much. According to one school of thought, our social needs can be summarised under three headings: autonomy, competence and relatedness.Footnote 37

Autonomy. We need a sense of agency – that we are in control of our lives.

Competence. We need to feel able to do what is needed of us.

Relatedness. We need to feel appreciated and to appreciate others – we need positive connections.

This may be true. But the specifics of what we desire depends hugely on the norms of the society in which we live.

Social comparisons

People are hugely affected by how they are doing compared with other people. They care about how their incomes compare with colleagues or how their children compare with other people’s children. We discuss this further in Chapter 13. People also tend to imitate each other. This sort of herd behaviour is generally the result of safety-seeking behaviour among members of a herd.Footnote 38

Conclusions

In the traditional economic model, people have well-defined preferences and pursue them consistently and selfishly. According to this model, wellbeing is efficiently promoted, in a laissez-faire world, except for various problems. The biggest of these problems is ‘externality’, which is the way in which people affect other people without their agreement.

However, there are in fact many other problems. Humans are different from the traditional economic model in many ways.

They often lack self-control (e.g., over drugs, alcohol and gambling), and what they plan for tomorrow they often fail to execute.

They often do not realise how much they will adapt to change, and they put effort into new acquisitions that make less difference to them than they expect.

They are hugely affected by how decisions are framed – for example, many will adopt a pension plan when it requires effort to opt out of it, but they would not choose it if they had to opt in to it.

People are hugely loss-averse, which often makes desirable changes much more difficult.

And, on the other side, they often help each other without expecting anything in return.

These complexities mean that government intervention or nudges are often needed to produce efficient outcomes. These arguments become even stronger when we consider the many pervasive ‘externalities’ affecting our experience:

We benefit if we live in a trustworthy society.

We get many of our norms and tastes from society.

Because of rivalry, we lose wellbeing if others are more successful.

Thus, the simple economic model explains a lot about the behaviour of companies and workers. But it is a very incomplete account of how people often behave. Clearly we need to understand why people behave as they do. But to know what behaviours should be encouraged, we also need to know how behaviour affects wellbeing. That is the central feature of the rest of this book.

Questions for discussion

(1) If people fail to pursue their own best interest, should the government ever do more than nudge them?

(2) What is the right mix of competition and cooperation?

(3) Whose job is it to produce good citizens: (i) parents, (ii) schools, (iii) government, (iv) faith organisations, (v) others?

(4) How useful is traditional economic theory for thinking about public policy? What are its main short-comings?

People are disturbed not by things but by the view they take of them.

Our experiences affect our wellbeing but so does the way we think about our experience – and about our future. The best evidence about this process comes when people are taught how to control their thoughts better. So in this chapter we examine three types of mind-training:

Clinical psychology (for people in distress),

Positive psychology (for all of us),

Meditation and mindfulness

The Experimental Method

In each area, we shall rely on evidence from well-controlled experiments. Such experiments are a vital part of wellbeing research. They are the surest way to establish causality in general and they are particularly important if we are trying to find out how to improve things. It is so easy to think that some method works – you see that those treated (the ‘treatment group’) improve. But would they have improved anyway? You can only answer this question if you had a ‘control group’ who were as similar as possible to the ‘treatment group’ but did not receive the treatment. The progress of the ‘control group’ then provides the ‘counterfactual’ with which you can compare the progress of the treatment group.

The gold standard for such a comparison is the randomised-controlled trial (or RCT). Here the treatment group and control group are drawn randomly from a single population. This does not guarantee that they are identical, but it hugely reduces the risk of conclusions that are biased because of pre-existing differences between the treatment and the control group.

The key issue with any intervention is the size of its effect. This is more important than whether the effect is or is not significantly different from zero (which also depends largely on the size of the sample).

The size of the effect can be measured in two ways. In the first, we measure it in units of the outcome being measured. For example, we could measure the effect in units of life satisfaction on a scale of 0–10 and find that an intervention raises life satisfaction by say 1 unit.

But it is also interesting to see how big this effect is, when compared with the overall spread of life satisfaction in the population. So suppose the standard deviation (SD) of life satisfaction is 2. Then this same intervention has increased life satisfaction by 0.5 standard deviations. This is the statistic known as the effect size (or Cohen’s d).Footnote 1 So for an outcome variable Y, the effect size of an intervention is given by

Effect size = Effect (in units of Y)/SD(Y) = Cohen’s d

Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy (CBT)

So, let us start with clinical psychology and ask, Are people in distress just victims of their past, who can only be helped by uncovering their past? Or can they improve their state of mind by changing their present pattern of thinking?

The leading exponent of the first view was the Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). According to Freud, our current feelings are largely the result of what happened to us in childhood. If our experience was bad, this has a lasting effect, especially if the memories of the bad experiences are ‘repressed’, buried deep in the ‘unconscious’ part of the mind. According to Freud, it is only if these memories are brought to the surface that the person can move forward. This is best achieved through psychoanalysis. Here the patient lies on a couch with the therapist behind him, while the patient practices ‘free association’. And, through this free association, the repressed memories come to light and the patient’s suffering is relieved.

Many people have been helped by Freudian treatment, though it is not easy to know how many, due to the paucity of controlled trials.Footnote 2 Freud was hugely influential on our culture, especially our greater openness about sex. But Freud’s view of human possibilities lacked optimism. In Civilisation and Its Discontents, he wrote: ‘The intention that man should be happy is not in the plan of creation.’

Most psychotherapists in the generation that followed Freud had a more optimistic view of human welfare. This was particularly true of Carl Rogers (1902–1987), who founded what he called humanistic psychology.Footnote 3 More than anyone, Rogers stressed the importance in psychotherapy of the therapeutic alliance between the therapist and the client, which is so central to much of counselling today. But the main focus of such counselling (now face-to-face) continued to be on understanding the past and how it has influenced the present.

The cognitive revolution

However, in the 1970s a completely new approach was developed by Aaron T. Beck. This approach was based on the key facts that

our thoughts affect our feelings,

we can (up to a point) choose to think differently

and therefore, we can directly affect our feelings.

This approach does not ignore the past (especially when it was traumatic). But it focuses on how our current thinking is maintaining the bad feelings that we have. These bad feelings are causing ‘automatic negative thoughts’. But we can observe these thoughts, question them (where relevant) and separate ourselves from them rather than being possessed by them. In this way, we can create space for more positive thoughts – for more appreciation of what we have and for better hopes and plans for the future. This will often involve a reassessment of our goals, since unattainable goals are one of the main causes of depression. We recover by ‘reframing’ our thinking.

Thus was born the ‘cognitive revolution’Footnote 4 – it was cognitive because it focused on cognition (i.e., thoughts). Beck’s main interest was the problem of depression. Trained as a Freudian psychotherapist, he had been taught that people were depressed because of repressed anger, which they redirect against themselves. According to this theory, that anger is revealed in their dreams and, from uncovering the anger, patients can be relieved of their depression. Wishing to make psychoanalysis scientific, Beck therefore arranged with a team of colleagues to compare the dreams of depressed and non-depressed people. It emerged that depressed people had less hostile dreams than other people did. Instead, the dreams of depressed people mirrored quite closely their conscious thoughts while waking – thoughts of being victims, with the world against them and themselves tormented, rejected or deserted.Footnote 5

So Beck altered his treatment. He got his patients to observe their ‘negative automatic thoughts’ and replace them with thoughts of a more constructive kind. In 1977, Beck published the first randomised controlled trial of cognitive therapy for depression, comparing it with the leading anti-depressant.Footnote 6 The results were striking – cognitive therapy was more effective. Since then there have been thousands of such trials, and the current wisdom is that cognitive therapy and anti-depressants are equally effective at ending a serious depressive episode.Footnote 7 But, after the depression ends, anti-depressants have no effect on the risk of subsequent relapse (unless you go on taking them), while cognitive therapy (once experienced) halves the subsequent rate of relapse.Footnote 8

The behavioural revolution in clinical psychology

Originally the ‘cognitive revolution’ in psychological therapy focused on depression. In the meantime, there was a ‘behavioural revolution’ in progress, for the treatment of anxiety disorders. This was based on the ideas of the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936), who showed how dogs could be conditioned to respond to a stimulus, depending on the good or bad events associated with the stimulus. The South African doctor Joseph Wolpe (1915–1997) inferred from this that humans who were currently terrified of doing something could be progressively desensitised by the step-by-step experience that nothing bad resulted when they did that something (like public speaking or going out of the house). He founded behaviour therapy.

In the 1960s, Gordon Paul put this theory to the test by doing the first controlled experiment in clinical psychology. The aim was to cure the phobia of public speaking. Paul compared systematic desensitisation with two other approaches: insight-oriented therapy (based on Freud’s ideas) and no treatment at all. Systematic desensitisation worked best.Footnote 9

In the decades that followed, people found that anxiety disorders were helped not only by behavioural methods but also by better styles of thinking. Likewise, depression was helped not only by better thinking but also by behavioural activation. And so was born Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy (CBT), which focuses on helping people change unhelpful patterns of thinking and thus bring about changes in behaviour, attitude and mood.

But CBT is not actually one thing. It is a set of different therapies for different problems. For example, for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), there has to be a detailed revisiting of the traumatic experiences. But the essential focus of CBT is on directly restoring people’s control of their inner mental life and thus enabling them to move forward. If undertaken with fidelity in the field, CBT produces a recovery rate of at least 50% after around 10 sessions – and for anxiety disorders the subsequent rate of relapse is very small.Footnote 10

Critics of CBT say, correctly, that it concentrates on dealing with the symptoms that are distressing the patient rather than on uncovering the causes of these symptoms. It is, therefore, they say, no more than a ‘sticking plaster’. But the test is surely the outcome as experienced by the patient. There is nothing wrong in dealing with symptoms rather than causes – it happens all the time in medicine, especially in surgery. The encouraging thing is that it gives immediate hope – that humans can take control of their inner life by conscious activity, properly trained.

CBT is not the only form of effective psychological therapy. For anxiety disorders it is the best, but for depression, UK government guidelines also recommend inter-personal psychotherapy, brief psychodynamic therapy and a specific form of counselling.Footnote 11 And of course drugs also help for severe depression and some forms of anxiety. But we have focused on CBT because it illustrates the key point of how our thinking can influence our mood.

Positive Psychology

If thoughts influence moods for people in real distress, the same must surely be true of everyone else also. This was the insight of Beck’s leading followers. In his presidential address to the American Psychological Association in 1998 Seligman proposed a new concept called Positive Psychology.Footnote 12 This applies the same principles as CBT to the lives of everybody. Everybody, it says, can be happier if they have better control of their mental lives and more sensible goals. The secret is to build on your strengths rather than to correct your weaknesses.Footnote 13 And to look for the best in any situation and the best in any person – to reach out and to feel grateful for what you have.

There are many good books on positive psychologyFootnote 14 and there are many controlled trials of the procedures it recommends, such as

a daily gratitude exercise and

a daily extra act of kindness.

At this point it is enough to present the 10 Keys to Happier Living, distilled from this literature by the movement called Action for Happiness. The five items in the left-hand column (see Figure 4.1) are five recommended actions for every day – the psychological equivalent to the daily five fruit and vegetables recommended by the WHO.Footnote 15 The five items in the right hand column are the main long-term dispositions we should cultivate in ourselves. To promote the 10 Keys, Action for Happiness has offered an eight-session course, which has been subjected to a randomised control trial. This showed that, two months after the course ended, the treatment group had gained over 1 point in life satisfaction (on a scale of 0–10), which is more than occurs when someone gets a job (after being unemployed) or finds a partner to live with.Footnote 16

Figure 4.1 10 Keys to Happier Living

A key issue in positive psychology is attention. What we focus on affects not only what we do (as in Chapter 3) but also how we feel. As we have seen, when humans evolved in the Savannah, there was a daily risk of being killed. So a high level of anxiety was functional, and it became embedded in our genes. As the psychologist Rick Hanson has put it ‘the mind is like Velcro for the negative and like Teflon for the positive’.Footnote 17 But in most of today’s world, people are much safer from violence than they have ever been.Footnote 18 So most people are more anxious than is good for them – they devote excessive attention to what goes wrong. The way to be happier is to devote more attention to what goes right.

Positive thinking has been subject to considerable criticism by those like Barbara Ehrenreich, author of Smile or Die, who says it encourages a Pollyanna attitude. According to these critics, it makes us overlook the bad stuff that is going on. Instead, these critics advocate ‘realistic thinking’. Obviously when it comes to other people, realism is vital – we should attend to their suffering. We need to notice it and help them – and the evidence shows that happier people are more helpful to others.Footnote 19 But, for ourselves, it is we who can, in part, create our own reality. The glass may be both half-empty and half-full: but how much better to think of it as half-full!

Meditation and Mindfulness

The habits encouraged by CBT and positive psychology have much in common with those advocated by Eastern wisdom, especially Buddhism.Footnote 20 The East has developed a more effective method of mind-training than is common in the West.Footnote 21 It is meditation. There are many forms of meditation, but the most common and the most studied is mindfulness.Footnote 22

Mindfulness means focusing on the present in an open, aware and non-judgemental frame of mind. You set aside the past and the future and you simply observe the present moment. You choose what you will attend to, and then attend to it. If your mind drifts off, you gently bring it back.

At first, the most natural object of attention is your breathing (where simple breathing exercises are also very useful).Footnote 23 But you can then move on to different parts of the body (including a full ‘body scan’), and then you can observe your thoughts, be they happy or sad. You do not push sadness or anxiety away, but you observe it from outside in a friendly way, so that it no longer possesses you. And you practice compassion towards yourself. If you feel you have done something stupid or wrong, you think, What would I say to a friend who was in this state? And you say just that to yourself.

Much mindfulness meditation in the West is based on Jon Kabat Zinn’s eight-session course of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) developed at the University of Massachusetts. This was originally a course for people in chronic pain, but it has proved very beneficial to many other people. For adults, MBSR has been found to have beneficial effects on mood and sleep, on substance abuse and on concentration and empathy.Footnote 24 It also affects the body. Mindfulness has been found to increase the amount of grey matter (critical for learning) and the regulation of emotion, and to increase telomerase, which increases longevity.Footnote 25 In one randomised trial, four months after the MBSR course was over, members of the treatment group and the control group were given a flu jab. The meditators produced more antibodies.Footnote 26

For children, comparable courses in mindfulness have been evaluated in a meta-analysis of 33 separate studies. They were found to have significant positive effects on depression (d = .22), anxiety (d = .16) and social behaviour (d = .27).Footnote 27 Some studies have also found good effects on academic learning.Footnote 28

Mindfulness meditation is totally non-judgemental. But there is another powerful strand in Eastern wisdom: the importance of compassion. A different form of Buddhist meditation focuses on developing compassion for others. In this, the meditator wishes first for her own wellbeing, then that of a loved one, then of an enemy and finally of all humankind. In a meta-analysis of 21 studies, this practice was found to increase wellbeing as well as compassion and to reduce depression and anxiety – all with effect sizes around 0.5.Footnote 29 Compassion meditation has also been found to increase levels of the feel-good hormone oxytocin and to improve the tone in the vagus nerve, which controls the heart rate.Footnote 30

Even so, there are some people for whom meditation does not work particularly well. But everyone can find some way of regulating their thoughts to improve their wellbeing.

All religions offer some way of doing this, but we leave the discussion of religion to Chapter 14. We can end this chapter with the Dalai Lama, who of all Eastern teachers has been the most influential in the West. He was until recently the head of the Tibetan government in exile but practices the life of a monk. He has also travelled and taught widely in the West. His many books teach ways to achieve happiness that may or may not include meditation. But at every stage the Dalai Lama, who has a strong scientific sense, stresses the unity of mind and body.Footnote 31 This is the theme of Chapter 5.

Conclusions

As we have seen, there are many interventions that can make us feel better through influencing our patterns of thinking and our reactions to the world around us. But these interventions tell us more than that. They show (through experiments) a more general truth: that how we think has a major effect on how we feel. Of course the opposite is also true: our feelings affect our thoughts, but it is mainly through our thoughts that we can manage our feelings.

Questions for discussion

(1) If a person is suffering, is it sufficient to ameliorate the symptoms, even if you cannot uncover or remove the cause?

(2) Is it ultimately dangerous to look on the bright side of things?

I have chosen to be happy because it is good for my health.

Our thoughts, feelings and behaviour do not occur in disembodied space – they occur in our bodies. This chapter investigates four big questions about the relationship between mind and body:

Can we locate our feelings in the brain?

How does our mental wellbeing affect the rest of our body?

How in turn does our body affect our mental wellbeing?

How do our genes affect our mental wellbeing?

Feelings and the Brain

Neuroscience is still in its infancy. But we can already locate areas in the brain where people experience their mental wellbeing and their distress. The method is to ask many people how they feel and then to correlate their answers with the electrical activity in different parts of their brains. The best method of measuring electrical activity in different parts of the brain is by functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI).Footnote 1 Using fMRI, significant correlations have been found between measures of wellbeing and electrical activity in a number of different brain areas. For example, Richard Davidson and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin have found a strong relationship with activity in the ventral striatum (and within it the nucleus accumbens).Footnote 2 The relationship holds both over time for the same person (as when a mother is shown a picture of her child) and also, more importantly, across people. Thus people with higher sustained activity in the ventral striatum report higher psychological wellbeing (see Figure 5.1). Their adrenal glands also produce less cortisol – another positive sign of wellbeing (see below).

Figure 5.1 Sustained activation of the ventral striatum predicts psychological wellbeing

The ventral striatum is a subcortical area that humans share with other mammals. But neuroscientists have also found correlation between wellbeing and activity in different parts of the pre-frontal cortex (including the ventro-medial and the dorsolateral).Footnote 3 Researchers have also identified a Default Mode Network in the brain that takes over when nothing much else is going on. It is focused on the self, and people where the network is more active report themselves to be less happy.Footnote 4

So there are objective measurements that correlate with reports of subjective experience, and this confirms that there is some objective information content in the reports of subjective wellbeing. But our understanding of the neural correlates of wellbeing is still quite partial.

More advanced is the neuroscience of pain. The main area where people feel distress when they are in pain is the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which is another subcortical area. Physical pain has two components – the ‘sensory’ aspect and the ‘emotional’ aspect. The sensory aspect informs us where the pain comes from (back, leg etc.) and its nature (e.g., pulsating, continuous, hot, cold), and it is recorded in the somatosensory cortex. But the emotional distress felt as part of the pain is located in the ACC.Footnote 5

So too, is the emotional distress resulting from social pain.Footnote 6 So it is not surprising that the pain-killing drug paracetamol (Tylenol in the United States) has the same dulling effect on the experience of both physical pain and social pain. In each case, the drug is moderating the electrical activity in the same part of the ACC.

So we already know something about where our conscious feelings of wellbeing and pain are experienced. But how does our mental life affect the rest of our body?

How the Mind Affects the Body

The clearest effect of the mind on the body is its effect on longevity. In September 1932, the mother superior of the American School Sisters of Notre Dame decided that all new nuns should be asked to write an autobiographical sketch. These sketches were kept, and much later psychologists independently rated them by the amount of positive feeling they revealed. These ratings were then compared with how long each nun lived. Remarkably, the amount of positive feeling that a nun revealed in her twenties was an excellent predictor of how long she would live. Of the nuns who were still alive in 1991, only 21% of the most cheerful quarter died in the following nine years, compared with 55% of the least cheerful quarter of the nuns.Footnote 7 This shows how happiness can increase a person’s length of life.

More recently, a random sample of English adults over 50 were asked questions about their happiness, and they were also asked whether they had been diagnosed with any long-term physical illness, such as heart disease, lung disease, cancer, diabetes or stroke.Footnote 8 They were followed for nine years to see if they died. The crude results are shown in Figure 5.1. The least happy third of them were three times more likely to die than the happiest third. And, even when controlling for all their initial physical illnesses, the least happy third were still some 50% more likely to die. Another study traced everybody in a Norwegian county over a six-year period. At the beginning, they were all diagnosed for their mental state and also asked other questions, such as whether they smoked cigarettes. Over the next six years, it turned out that diagnosed depression was as powerful a predictor of mortality as smoking was (Figure 5.2).Footnote 9

Figure 5.2 Percentage dying over the next nine years (People originally aged 50 and over)

What explains this effect of mood upon physical health? The clearest channel is through the effects of stress. The body has a mechanism that responds to stress in a similar way whether the stress is physical or mental. This is sometimes called the ‘fight or flight’ response: our heart rate, blood pressure and breathing rate increase; we sweat more and our mouths go dry.

This response begins in the brain, which is linked to the rest of the body by two main sets of nerves. One set includes the sensory nerves and the motor nerves, which give conscious instructions to our limbs about what to do. But the other set is the ‘autonomic nervous system’, which is largely outside our conscious control and regulates the workings of all our internal organs.

The autonomic system has two main branches: the sympathetic and the para-sympathetic. It is the sympathetic nervous system that initiates the fight or flight response. It immediately instructs the adrenal gland to produce what Britons call adrenaline and Americans call epinephrine. This is a hormone (Greek for messenger) that enters the bloodstream and galvanises the whole body for action. It also mobilises the immune system to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines in case they are needed to handle possible infections. The parasympathetic nervous system, in contrast, calms the body. When it is active, the body’s organs become less active. For example, in meditation or breathing exercises the vagus nerve is active in reducing the heart rate. But, so long as stress is maintained, it is the sympathetic system that is most active.

At the same time, a second hormone is produced in another part of the adrenal gland: cortisol. A message goes from the brain’s hypothalamus to the pituitary gland to the adrenal gland, which releases cortisol into the bloodstream, and this then stimulates the muscles by releasing their store of glucose.

The stress response is totally functional when the stress is brief. But when the stress is persistent, it can lead to over-activity of the immune system (especially of C-reactive protein and IL6) and to persistent inflammation around the body, which eventually reduces life expectancy.Footnote 10 It also leads to more fibrinogen in the blood – intended to cause blood clots in a wound but unwanted in the longer term. In Western countries the most common sources of prolonged stress are psychological, and increased inflammation has been observed as a result of marital conflict, caring for demented relatives, social isolation, social disadvantage and depression.Footnote 11

Another cause of stress with long-lasting effects is child abuse. One study followed children born in Dunedin, New Zealand. Those who had been abused in the first ten years of life had increased markers of inflammation twenty years later.Footnote 12 These findings on child abuse are confirmed in a meta-analysis of many comparable studies.Footnote 13 By contrast, optimism and purpose in life protect against coronary heart disease and stroke.Footnote 14

Perhaps the simplest evidence of the effect of mind on body comes from a simple experiment. In it people were given a small experimental wound. Those who were depressed or anxious took the longest to recover.Footnote 15 In another experiment, people were given injections, and people in the greatest psychological distress developed the fewest antibodies.Footnote 16 Since we can affect the mind by psychological intervention, we can also affect the body that way. For example, mindfulness meditation reduces the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines.Footnote 17 It also increases the production of telomerase, which increases life-expectancy.Footnote 18

Perhaps the most striking effect of the mind on the body is the placebo effect. For many diseases, up to 30% of people given a placebo pill (with no active ingredient) will recover.Footnote 19 People recover because they believe that they will.

So the mind has profound effects on the body. These are a major part of how our wellbeing is generated, and the different chemicals involved provide useful biomarkers of how our wellbeing is developing.

How the Body Can Affect the Mind

But there is also a stream of causation going in the opposite direction – from our body to our wellbeing. Bodily events can alter our mental state. Healthy living is vital for our mental wellbeing and this means plenty of exercise, enough sleep and good sense in drinking and eating.Footnote 20 Equally, physical illness and dementia reduce our wellbeing.

But one of the clearest examples of the effect of the body on the mind is the power of drugs, be they recreational or psychiatric. These work by affecting the operation of chemical ‘neurotransmitters’, which are crucial to the working of the brain. The brain consists of about 100 billion brain cells or neurons, and each neuron is connected to thousands of other neurons. Messages travel round the brain one neuron at a time. When that neuron ‘fires’, an electrochemical impulse travels from one end of the neuron to the other. But then it reaches a gap between that neuron and the next neuron. This gap is called a ‘synapse’ and the message is carried across the gap from the sending neuron to the receiving neuron by a chemical neurotransmitter.Footnote 21

So the different circuits in the brain are operated by different neurotransmitters:

Serotonin produces a good mood.

Dopamine and acetylcholine are neurotransmitters that stimulate (and can heighten) mental activity. (A ‘high’ feeling is generally associated with a rush of dopamine).

GABA (gamma aminobutyric acid) and endocannabinoids reduce mental activity.

Drugs affect the operation of a neurotransmitter. Some stimulate production of a neurotransmitter, others reduce its production, while others bind to the same receptors as some neurotransmitters and thus have a similar effect as the neurotransmitter that they mimic. Table 5.1 shows how the main recreational drugs alter our mental state, through the way in which they alter the operation of the neurotransmitters. Unfortunately, all these drugs can be addictive.Footnote 22

Table 5.1 Some recreational drugs and their effects

| Effect | Drug | Effect on main neurotransmitters |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulant | Ecstasy (MDMA) Cocaine, amphetamines Nicotine | Increases serotonin Increases dopamine Mimics acetylcholine |

| Sedative/relaxant | Alcohol, barbiturates Cannabis | Increases GABA Increases endocannabinoidsFootnote * |

| Pain relief | Opiates (heroin, morphine) | Mimics endorphinsFootnote ** |

* Can also increase dopamine, acting as a stimulant. **Endorphins are endogenous morphines, hence their name.

There are, however, other drugs that can make people feel better: psychiatric drugs. These are generally less addictive. Table 5.2 shows some of the psychiatric drugs recommended for different psychiatric conditions. Take one example, Prozac. This is a psychiatric drug that increases the flow of serotonin and thus activity in the circuits that it serves. It does this by inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin, thus increasing the supply of serotonin and improving mood. In other words, it is a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). In many depressed patients, Prozac improves mood. Clearly dopamine is a tricky neurotransmitter: increasing it can be stimulating, but an excess of dopamine leads to schizophrenia (and a deficiency of dopamine to Parkinson’s disease). Like psychological therapy, psychiatric drugs do not always work. They are, however, strongly recommended for severe depression, where they achieve 50% recovery rates. But they have no effects on relapse unless they continue to be taken.

A key fact about the brain is the ease with which it can be altered by experienceFootnote 23 – in other words, there is a high level of ‘neuroplasticity’. Blind people use part of their visual cortex to hear. And London taxi drivers have to remember so many streets and routes that they develop abnormally large hippocampal areas in their brains.Footnote 24 There are many places in this book where we shall report the effect of wellbeing interventions on brain activity.

How Our Genes Affect Our Wellbeing

The one part of our body that never changes is our genes. They were determined at the moment of our conception and, apart from mutations, we keep the same genes throughout our life. The same genes are present in the nucleus of nearly every cell in our body. It is the continuity in our genes that explains much of the continuity in our personality, our appearance and our behaviour over our life.

But how do we know this, and how far do differences in our genes explain the differences in wellbeing in the population? To explore these questions, we shall proceed this way.

(1) We shall examine twins and show that identical twins (with the same genes) are much more similar to each other in wellbeing than non-identical twins are (with many different genes).

(2) We shall look at adopted children and show that they still resemble their biological parents in many ways.

(3) We shall show that the genes and the environment do not have independent effects on our wellbeing – they interact. Therefore, it is not possible to say in any meaningful way how much of the spread of wellbeing is due to differences in genes and how much to differences in environment.

(4) We shall describe the pioneering search for the specific genes that affect wellbeing.

(5) Finally, we shall examine the inter-relation between genes, personality and wellbeing.

Evidence from twins

To see that genes matter we have only to look at the following data on Norwegian middle-aged, same-sex twins (see Table 5.3). Some of the twins are identical: both come from the same egg. They therefore have the same genes and look more-or-less identical. The other sets of twins are non-identical: each twin comes from a separate egg. So half her genes are the same as her co-twin’s but half are different (just as is the case with any other pair of siblings).Footnote 25 And what a difference that makes! As Table 5.3 shows, if the twins are identical, their life satisfaction is fairly similar (with a correlation across the 2 twins of 0.31). But if the twins are non-identical, their enjoyment of life is much less similar (with an across-twin correlation of only 0.15).

Table 5.3 Correlation in life satisfaction between each twin and his/her co-twin (Norwegian adults in mid-life)

| Identical twins | 0.31 |

| Non-identical twins | 0.15 |

| Difference | 0.16 |

What could account for this difference? Clearly it must be because the identical twins have genes that are more similar. Even though both sets of twins were raised together, their final wellbeing was very different. This suggests that the family environment has a smaller influence than many people suppose.

Countless twin studies testify to the effect of our genes not only on our wellbeing but also on our mental health. For example, if you are bipolar and you are an identical twin, then the chance that your co-twin is also bipolar is 55%. (That is the degree of ‘concordance’.) But, if your co-twin is not identical, the chance is only 7%.Footnote 26 Thus if someone has bipolar disorder, the risk to the co-twin is a huge 48 points higher (55%–7%) if the co-twin is identical rather than non-identical. Figure 5.3 gives comparable numbers for many other types of mental illness. In every case, the difference is substantial. That is an astonishing testimony to the power of genes.

Figure 5.3 Difference between identical and non-identical twins in the concordance between twin and co-twin

Note: For each condition, we calculate the concordance for identical same-sex twins and for non-identical same-sex twins and report the difference. For OCD, alcoholism and all childhood conditions except autism, we give the difference in co-twins’ correlation (on a continuous measure). For rare binary conditions, the concordance and the correlation are very similar

Evidence from adopted children

A different approach to the same issue is to look at adopted children and ask, Are they more similar to their adoptive parents or to their biological parents? Until the 1960s it was assumed (largely due to Freud) that mental illness was chiefly caused by how our parents behaved. But in 1961, Leonard Heston of Oregon University published his classic paper on schizophrenia. Heston studied adopted children and what he found was remarkable. One per cent of these adopted children became schizophrenic (the same as other children) – unless their biological mother was schizophrenic. But in that case 10% became schizophrenic. So it was the mother’s genes that made the difference rather than the behaviour of their live-in adoptive parents. And in fact, if you had a mother with schizophrenia, you were no more likely to become schizophrenic if you lived with her than if you did not.Footnote 27 Not all adoptive studies are as striking as Heston’s. For depression and anxiety disorder, they yield less striking results. But they are not inconsistent with the evidence from the twin studies that we have just looked at.Footnote 28

When studying wellbeing, a key source of evidence has been the Minnesota Twin Registry, which includes twins who were raised together and twins who were raised apart (as adoptees). The study showed that identical twins raised apart were much more similar in wellbeing (r = 0.48) than non-identical twins brought up by their biological parents (r = 0.23).Footnote 29 This again underscores the importance of genetic factors.

Heritability

A natural question now is to ask What fraction of the variance of wellbeing across individuals is due to the genes?Footnote 30 In other words, what is the heritability of wellbeing? Questions on heritability are usually answered using some strong assumptions, which we will question later.

We assume an additive model with (in its simplest form) two components – G for the genetic component and E for the environmental component. Thus wellbeing (W) is determined by W = G + E. It follows that the variance of wellbeing equals the variance of the genetic component plus the variance of the environmental component plus twice the covariance of the genetic component and the environmental component:

Crucially, in behavioural genetics this covariance is considered to be due to the genes. But in truth, it can be as much due to the environment as to the genes. For while it is certainly true that people with good genes are skilful at finding good environments, it is equally true that in most societies good environments are more receptive to people with good genes.Footnote 31 So the first arbitrary assumption in behavioural genetics is that individual outcomes related to genes are caused by genes. The second arbitrary assumption (to which we shall return) is that there are no gene-environment interactions.Footnote 32

But if we wish away these two problems, we can show that the heritability of a trait (like wellbeing) equals twice the difference between the correlation of the trait across identical twins and its correlation across non-identical twins.Footnote 33 So if we use the numbers in Table 5.1, the heritability of life satisfaction is 2 (0.31−0.15) = 32%. This is a typical estimate of the heritability of life satisfaction obtained from twin studies worldwide.Footnote 34

Genes and environment

So the genes really matter. But so does the environment that we experience. In fact, the environment is generally more important. Even with the most heritable mental trait that we know of (bipolar disorder) only just over a half of the co-twins of bipolar people also have the condition. And for most conditions it is much less.

Moreover, genes do not operate on their own, with the environment just adding further effects. Rather, the genes and the environment interact, with the genes influencing the effect that the environment has on us and vice versa. This we can see clearly in the following study of the impact of negative life events on a sample of twins in Virginia.Footnote 35 Negative life events included the death of a loved one, divorce/separation and assault. And the issue was how frequently did those people who had a negative event experience a major depression in the subsequent month?

Therefore, for each individual the study measured

(i) what negative events they experienced,

(ii) whether major depression followed within a month and

(iii) the mental health and relatedness of the individual’s co-twin.

As Table 5.4 shows, a person was more likely to experience a major depression if their co-twin was depressed (especially an identical twin who was). And they were less likely to be depressed if their co-twin was non-depressed (especially if it was an identical twin). This is a clear case where people have bad experiences but the effect depends also on how far their genes predispose them to depression.

Table 5.4 Chances of onset of major depression within the month following a severely stressful life event

| Condition of co-twin | Chances of depression within the month(%) |

|---|---|

| Co-twin depressed and identical | 14 |

| Co-twin depressed and non-identical | 12 |

| Co-twin non-depressed and non-identical | 8 |

| Co-twin non-depressed and identical | 6 |

Evidence of such interaction is ubiquitous. For example, in one study of adopted children anti-social behaviour was more common in adolescents if their adoptive parents were anti-social. But the effect was greater still when the biological parents were also anti-social.Footnote 36

There is however some encouraging news. As we have seen, people with unfavourable genetic predispositions respond worse to bad events than other people do, but they also respond better to good events.Footnote 37 For example, children who carry the unfavourable variant of the gene most closely related to depression can respond better to CBT than other children do.Footnote 38

The interaction between genes and environment in determining wellbeing should not come as a surprise. For such interactions are also common in physical health. A classic case is the disease known as phenylketonuria (which produces mental retardation). To get the disease requires two things:

First, you need the unfavourable gene.

Second, you have to eat phenylalanine, which is present in many foods.

If you avoid the foods, you don’t get the disease.Footnote 39 So, even for people with unfavourable genes, we can greatly improve their lot by improving the environment.

Evidence from DNA

The previous discussion does not rely on any actual data on genes – you just compare the wellbeing of different pairs of twins or adoptees. But today we can sequence the actual DNA that each individual carries. There are millions of positions on the string of genetic material, and at each position, one of three variations is present. These variations are known as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (or SNPs, pronounced Snips). With the aid of this information we are able to get more direct evidence on the roles of genes.

For wellbeing, a comprehensive study of 11,500 unrelated people and over half a million SNPs assessed the genetic similarity of every possible pair of people in the sample. By relating this to the difference in their wellbeing, it showed that people’s genes (treated as additive) explained 5–10% of the variance in their wellbeing. This is a minimum estimate since it omits the effect of any interaction between different genes.Footnote 40

A different and potentially important endeavour is to discover which specific genes make the most difference, through genome-wide-association studies (GWAS), which look for the effects of each gene upon the trait in question. The first pioneering study was able to find three SNPs that passed the test of significant effects on wellbeing.Footnote 41 Each SNP explained 0.01% of the variance of wellbeing. A more recent study has been able to identify 148 significant SNPs, which together explain 0.9% of the variance. This is partly due to larger sample size and precise measurement of the outcome, and further work will then further increase our understanding.Footnote 42

The conclusion is that there is no single gene for happiness, or even a small number of genes. Instead, thousands or more genes are involved, interacting in complicated ways with each other and with the environment. Taken together, these genes predispose people to more or less happy lives.

Personality and Wellbeing

As we have seen, an important way in which genes affect our wellbeing is through our mental health. But a more general way is through all aspects of our personality. Psychologists find that much of the variation in character that we experience in those we encounter can be described by five dimensions. These are Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism (which spell OCEAN). Some of these dimensions appear to be poorly correlated with our life satisfaction. But two are highly correlated with life satisfaction. These are neuroticism (as you might expect from our earlier analysis) but also extroversion. So, if we revert to the mid-life Norwegian twins we discussed at the beginning of the chapter, personality overall explains about a third of the variance in wellbeing. And personality itself is partly determined by our genes (see Table 5.5). So a significant part of the heritability of wellbeing comes from the heritability of personality.

Table 5.5 Correlation between twins and their co-twins in various aspects of personality (Norwegian adults in mid-life)

| Identical twins | Non-identical twins | |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | 0.56 | 0.27 |

| Extraversion | 0.46 | 0.27 |

This said, it is crucially important to recognise that personality (like wellbeing) varies substantially over the life course. Not only do we on average become more conscientious, agreeable and emotionally balanced over time, but we also become less open and less extrovert. And we also change a lot relative to our contemporaries – due to differences in how life treats us.Footnote 43 Genes are important, but from now on we concentrate on the effect of what policy-makers can affect – namely our experience of the environment in which we live.

Conclusions

(1) Self-reported wellbeing is correlated with activity in a number of brain areas. The sensation of pain is most clearly experienced in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which registers both physical pain and social pain.

(2) The mind affects the body. Wellbeing predicts mortality as well as smoking does. Prolonged psychological stress leads to excessive production of adrenaline/epinephrine and cortisol, over-activity of the immune system and excessive inflammation in the body. Mindfulness meditation reduces these effects and increases life-expectancy.

(3) The body affects the mind. The most obvious effects are those of drugs, recreational and psychiatric.

(4) Genes have important effects on our wellbeing. We know this in two ways.

Identical twins (who have identical genes) are much more similar to each other in their wellbeing than are non-identical twins (who share only 50% of their genes).

Adopted children are more similar in mental health to their biological parents than to the parents who raised them.

It is important that parents and professionals realise the importance of these genetic effects and do not automatically blame parents’ behaviour for the problems of their children.

(5) It is, however, not possible to neatly separate the effects of the genes and the environment for two reasons:

Genes and environment often interact in their effects on wellbeing.

Genes and the environment are correlated, and there is no simple way to apportion that part of the variance of wellbeing that comes from the covariance of genes and the environment.

And we should never assume that, because a problem is partly genetic in origin, it cannot be treated as effectively as one that is primarily environmental.Footnote 44

This completes our review of some basic processes common to all humans – our behaviours, thinking styles, physical processes and genes. It is time to turn to the impact on us of specific features of our experience.

Questions for discussion

(1) Does the evidence from the brain make people’s self-reports any more credible?

(2) How important is the mind in explaining physical health?

(3) How far can drugs of all kinds improve our wellbeing?

(4) Does it help to know how far a person’s wellbeing is affected by their genes? In what ways might it help?

(5) What does it mean to say that for most purposes genes and environment interact to determine character?

(6) Why is it so difficult to say what proportion of the variance of wellbeing is due to the genes?

(7) If something significantly influenced by genes, is it automatically more difficult to change than something mainly due to the environment?