On Friday, 3 September 1875, 281 incarcerated women and four children woke up in Mountjoy Female Convict Prison in Dublin.Footnote 1 The prison housed all of Ireland’s serious offenders who had received sentences of incarceration of three years or more. The women would spend their day variously employed in the almost exclusively female space: 115 sewing, 47 in the laundry, 15 tailoring, 9 knitting, 4 plaiting, splicing or winding yarn, and 1 breaking bones. Nine incarcerated women cooked the prison meals, which were generally eaten in the individual cells where inmates slept, 4 worked as assistant nurses in the prison hospital tending to the 28 sick inmates, and 1 helped the teacher in the prison school where 153 women were taught that day. Nine women were chastised for breaking prison rules. A prison matron accompanied two prisoners to St Vincent’s Reformatory, also known as Goldenbridge Refuge in Inchicore, Dublin, a halfway house between prison and release run by the Sisters of Mercy, where they would serve the final part of their sentences. They joined 53 Roman Catholic women similarly transferred in the months previously. Six women spent the night in the city’s Protestant equivalent, known as The Shelter. Thirteen children, the offspring of incarcerated women, were in state-funded foster care awaiting their mothers’ release. In many ways it was an unremarkable day in Ireland’s only female convict prison. But for the 279 inmates who lay down in the prison that night, the 61 women who went to sleep in Dublin’s convict refuges, and the 17 children uprooted by their mothers’ convictions, it was another day closer to release or reunion.Footnote 2

Women featured in this study were sentenced to penal servitude for an average of 5.5 years, although practices of remitting time for good behaviour meant that they did not always serve the complete sentence.Footnote 3 Sentences of penal servitude, imprisonment in a convict prison, were introduced in the mid-1850s to replace transportation. Female convicts were accommodated in Grangegorman Female Penitentiary and Newgate Auxiliary Prison in Dublin and in Cork Female Convict Depot. Provision for women was expanded after the opening of a singular prison for convicted women, Mountjoy Female Convict Prison, in 1858.Footnote 4 Judges sentenced women to penal servitude in the convict prison when dictated by the nature of their crimes or when imprisonment in a local institution was deemed inadequate. The latter was subjective and likely influenced by factors such as appearance and demeanour, family background, age, previous conduct or criminal record. Mary O’Neill was sentenced to five years of penal servitude for stealing clothing in Dublin in 1878, ‘as she appeared to be an old offender’.Footnote 5 The judge who tried Margaret Mellia in Carlow in the following year sought to justify his decision: ‘It was upon all hands agreed she was a perfect nuisance if I may so say and that nothing but penal servitude w[oul]d cure of her Evil ways.’Footnote 6 Charlotte Mallowney received a sentence of five years for stealing in Dublin in 1867, ‘in the hope that a residence in the Reformatory, to which women are usually sent after a prolonged period of imprisonment in the convict Prison when sentenced to penal servitude, might lead to a change in her conduct and character’.Footnote 7

Prison reformer Mary Carpenter complained of diversity in sentencing.Footnote 8 Some judges also recognised their subjectivity. In 1861 Undersecretary for Ireland Sir Thomas Larcom reviewed Judge Jackson’s 1855 decision to sentence Johanna O’Brien to transportation for life for forging cheques on the bank account of the father of her four-year-old child. Larcom admitted: ‘I find it very difficult to account for the very severe sentence passed in this case.’Footnote 9 O’Brien was not transported because the practice of transporting women to Australia had ended by this stage and was replaced by penal servitude in the convict prison. At the time of the trial, she defended her actions, noting ‘I think I have a claim on’ the father of her child, but this view was not shared by Judge Jackson or by the Limerick gaoler, Henry Woodburn, who wrote of O’Brien’s ‘very bad morals. Intriguing with a married man.’Footnote 10 Woodburn clearly viewed O’Brien as exclusively responsible for her son’s welfare as well as the affair. Sometimes judges could not explain their own decisions in the aftermath of a trial. The judge who sentenced Mary Pickett to penal servitude for seven years for receiving stolen goods in 1880 admitted a few years later: ‘I have no recollection of the grounds upon which I passed the sentence of Penal Servitude.’Footnote 11 She remained in custody until August 1885.

Women’s reactions to the lengths of their sentences or to convict rather than local imprisonment can occasionally be determined. Catherine Alcock’s mother considered that the ‘most firm minded person would receive a shock on hearing a sentence of 5 years penal servitude pronounced’. She judged her daughter’s reaction after having been found guilty of stealing clothing from a house in 1861: ‘I am only surprised when penal servitude was mentioned to her that she did not take her illness in the Dock and lose the lives of both herself and the Infant she was carrying’.Footnote 12 Anne Lynch’s frustration at her seven-year sentence for larceny in 1870 is evident from her behaviour when taken from the dock in County Tyrone. Described as a ‘very troublesome refractory and dangerous woman’, Lynch allegedly:

made a violent blow at the governor of the gaol who avoided it but received a severe kick on the thigh which was aimed at another part of his body. The police then caught her when she struck one of them in the face and kicked another, although she had at same time a child in her arms.Footnote 13

Johanna Joyce, ‘the wife of a travelling tinker who … discarded her on account of her violent temper and general bad character’,Footnote 14 responded with shrieks of horror to her three-year penal servitude sentence for stealing in 1893. As the twenty-six-year-old, who had already served several sentences in local prisons, was taken from the Tullamore court in King’s County, the judge reassured the jury: ‘I know what I’m about gentlemen; she’ll be well taken care of by the nuns. It’ll be a sort of Industrial School.’Footnote 15 The judge’s opinion of the convict prison differed drastically to Joyce’s. In a private letter he explained that he issued this sentence ‘to save her from herself’.Footnote 16 Ellen Shea, charged with the same offence in the same year, showed less concern. When the judge at her trial in County Waterford asked her if she had anything to say, she defiantly retorted: ‘No, the jury can find me guilty and you can sentence me to death, Ta-ra-ra-Boom-de-ay’.Footnote 17 She was sentenced to three years.

Different reactions to sentences reflect the diverse personalities of the women housed in Ireland’s female convict prison. Patricia O’Brien reminds us that prisoners ‘did not leave their identities and roles in free society outside the prison gates. They did not adopt totally new behavior patterns particular to the prison but instead brought into the prison with them their experiences in free society.’Footnote 18 The personalities of inmates in the porous convict community at any one time, informed by age, background, occupation, previous convictions, family circumstances and marital or parental status, influenced experiences for everyone. This study traces the multiplicity of female convict experiences in the period after the establishment of convict imprisonment in 1854 to the end of the nineteenth century. It aims to demonstrate how individual women, as well as the inmate cohort as a whole, experienced convict life, as far as this is possible from the records.

The prison interior was a private space, beyond the direct reach of the general population. But it was also government property, a space subject to a staff and inmate gaze and visited by prison inspectors and other government officials, philanthropists, men and women religious, journalists, travellers, handymen or other contracted professionals, and relatives or friends of inmates and staff, whose published or verbal accounts would have brought the prison to the public. At the top of the prison hierarchy was the superintendent, who reported to the prison directors at Dublin Castle, the Irish administrative headquarters since the Act of Union, 1801, established the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Below her were the deputy superintendent and principal matron (of which there were generally two), followed by the laundry matron, school matron, instructress of works, class matron and assistant matron.Footnote 19 By 1858 all female convict prison employees were women, except the gate porters and night watchmen.Footnote 20 Other men associated with the prison included the medical officer and religious chaplains. Staff quarters were provided for some employees and their families.Footnote 21 The prison was thus a place of employment as well as containment, and a temporary home to prisoners and staff and their offspring. This book considers the prison as a material and ideological space where nineteenth-century ideas about penology, criminality and femininity intersected with lived realities.Footnote 22 My focus, however, remains on the prisoners and their social realities rather than the politics of the institution in which they were housed, and my concern is less with the rhetoric of female criminality and imprisonment generally than with the experiences of women in the Irish convict prison system.

This book explores relationships that developed across the prison space. The institution was designed and conceptualised largely by men in positions of authority to house women whose liberty was curbed by their confinement. Drawing on Foucault, Rob Boddice argues that institutional space represents societal hierarchies and thus directs social interaction.

By such reasoning an architectural plan can have an emotional regime in mind. … Emotional expression is literally bounded according to which side of the bars, or which side of the desk, a person finds himself. Behaviour is limited by the clear demarcations of what a person is according to where he is.Footnote 23

But, as Boddice identifies, occupants can adapt or appropriate their space.Footnote 24 Women who spent years in the institution used the space to form relationships, to seek or provide emotional support, to gain economically or otherwise. Prisoners challenged ascribed power and, in relationships with staff members, sometimes contrived expected power dynamics. This book asks questions like: How did prisoners interact with one another as well as those paid to restrain them? Where did they get practical or emotional support given that they were in most cases locked away for years from their families? How did they maintain contact with loved ones if so desired? It considers how crime or criminal background, or differences such as class, age, religion, regionality or position within the prison affected hierarchies and networks. And it examines the nature of such relationships in prison and after release.

The convict women studied in this book were variously described by those who encountered or imagined them. English writer Fanny Taylor saw upon her visit in the 1860s ‘miserable inmates … wild, desperate women, with great physical strength and easily-roused passions’.Footnote 25 Author Margaret Gatty, visiting from England, portrayed in 1861 a ‘shocking-looking set of creatures … one felt in their presence that sin does really deform the outer, as well as the inner man’. She dehumanised the women through her gaze, perhaps influenced by her background in marine biology: ‘This is the only female convict prison in Ireland, so we had a full specimen of this painful subject of study.’Footnote 26 A male writer commissioned by the Freeman’s Journal to write about Mountjoy surmised in 1871, ‘I suppose no man, except a professor of calisthenics, cares to be alone amid a couple of hundred women; but when the women are all ugly, miserable, criminal, wo[e]ful women, the business is infinitely distressing.’ His views encapsulated attitudes towards female criminals who had seemingly transgressed moral as well as gender expectations:

When you find yourself in a room with female convicts most of your proceedings are hap-hazard. You never know whether to say a pleasant word or to be quite neutral in your manner; to take off your hat or walk about as if amongst men; in fact you find yourself sorely puzzled as to how you shall demean yourself before the dumb wretches who have forfeited every claim to homage and sympathy.Footnote 27

As Lucia Zedner has identified in an English context, ‘While the male offender was merely immoral, his female counterpart was likely to be seen as utterly depraved irrespective of any actual, objective difference between them.’Footnote 28 Men were condemned for their criminality, L. Mara Dodge notes, but were not perceived to challenge expectations of masculinity in a way that female criminals were thought to have defied notions of femininity.Footnote 29 Women’s reformation in prison was thus considered a necessary challenge given their expected influence on the next generation.Footnote 30 Captain Walter Crofton, who headed the Irish convict department from the 1850s, outlined the repercussions of such views in 1866: ‘In the face of certain publications, which have tended to increase both the alarm and disgust felt by the public with regard to female convicts, it has not been an easy task either to procure them employment when liberated, or to obtain work for them in the refuge.’Footnote 31 Irish convicts in Australia were often viewed more negatively than their British, especially English, counterparts.Footnote 32 Ethnic differences between the watcher and watched might likewise have influenced some English writers’ views of incarcerated Irish women.

The prison space and experiences produced therein were products of their time. An assessment thus allows for an understanding of contemporary attitudes towards women, crime and punishment. It demonstrates realities of institutionalisation at a time of massive institutional growth across Ireland, particularly for non-conforming women.Footnote 33 In 2015 Christina Brophy and Cara Delay observed that despite recent research on Irish women’s history ‘we still know little about the lives of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century women, particularly the poor, ordinary, or outcast’.Footnote 34 The women incarcerated in Ireland’s convict prison were exceptional in having been found guilty of a crime and in having been sentenced to penal servitude. But despite the views proffered by some writers who saw them behind bars, they were, in many respects, ‘ordinary’ women.Footnote 35 An exploration of their documented experiences thus has the potential to reveal much about their lives, and by extension the lives of women like them outside the confines of the prison. It offers an insight into nineteenth-century survival strategies and women’s agency, their networks, struggles, responsibilities or transient lifestyles dictated by economic need. Individual cases show the harsh realities and consequences of poverty in Ireland. They point to women’s relationships with parents, children, siblings or other relatives, partners, friends or rivals. The microhistory of the Irish female convict prison is bound up in the macro-history of contemporary gender, class, economic and other relations and expectations, as well as Irish social history more generally.

The Irish Convict System

Historians such as Tim Carey, Patrick Carroll-Burke, Elizabeth Dooley, Richard Hinde, Rena Lohan, R. B. McDowell, Conor Reidy and Beverly Smith have mapped a thorough account of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Irish penal developments in local and convict prisons that need not be repeated.Footnote 36 The nineteenth century brought developments across Europe as the emphasis on prison as a site of punishment was gradually diluted by ideas about its reformatory potential. O’Brien sums up changes in France, where ‘old-regime jails and prisons … often no more than large communal rooms teeming with people of all ages and both sexes, those awaiting trial and those convicted, for all types of crimes, beggars, murderers, pickpockets, and prostitutes’ were replaced by new-style prisons, ‘honeycombed with isolated units, with highly regimented and supervised collective activities during the day’.Footnote 37 Such changes were gradual in Ireland, with new ideas about the punishment and reform of prisoners clashing with spatial restrictions of old prison buildings. Influential penologists and prison reformers such as Jeremy Bentham, Mary Carpenter, Jeremiah Fitzpatrick, Elizabeth Fry, John Howard and others disseminated ideas, initiated or inspired the establishment of organisations for the promotion of prison reform, and influenced politicians and officials. Increasing institutionalisation was also seen across this period with the building of workhouses, so-called lunatic asylums, industrial schools, reformatories, mother and baby homes and Magdalen asylums.

By the mid-nineteenth century the prison system was heaving under multiple pressures. Although, Dooley observes, the death and emigration associated with the Great Irish Famine, 1845–9, meant a lower population in Ireland than in previous years, the introduction of the Vagrancy (Ireland) Act in 1847, which Reidy describes as a ‘disastrous miscalculation by the British government’, served to increase the numbers of women, men and children in prison.Footnote 38 This was compounded by legislation that reduced the crimes for which a convict could be punished by transportation, ensuring that more convicts had to be accommodated at home.Footnote 39 The Penal Servitude Act, 1853, abolished transportation sentences of less than fourteen years, introduced penal servitude as a punishment, and equated penal servitude sentences for some convicts in lieu of transportation.Footnote 40

The threatened cessation of transportation to Australia also materialised in 1853. Although, Davie recognises, the ‘writing had been on the wall for some time in fact, with mounting criticism at home and one Antipodean door after another slamming shut in the face of the Mother Country’s criminal export trade’,Footnote 41 this caused a critical situation in the Irish convict prison system that had come to rely on transportation.Footnote 42 In addition to requiring prison space for many more convict bodies, authorities perceived a need to devise a reformative system so that a convict after release ‘did not fall back into the stream of society in this country to contaminate it by her example’.Footnote 43 Many hoped for the reintroduction of transportation; in 1859 Grangegorman Female Penitentiary superintendent Marian Rawlins expressed her ‘earnest hope that some colony may yet be found … away from the allurements which might tend to shake the foundation of reformation’.Footnote 44 But it was not to be. Mass transportation of convict women was not again officially sanctioned. The Penal Servitude Act, 1857, replaced transportation sentences with penal servitude.

The Act for the Formation, Regulation, and Government of Convict Prisons in Ireland, 1854, directed the establishment of ‘Convict Prisons’, described as ‘places of confinement either at Land or on board Vessels to be provided for that Purpose for Prisoners under Sentence or Order of Transportation or of Penal Servitude’.Footnote 45 The act facilitated the appointment of up to three directors of convict prisons who would sit in Dublin Castle.Footnote 46 The directors were responsible for all convict prisoners and prisons, and governors and superintendents would report directly to them. They had no authority over local prisons that housed women, men and children sentenced to shorter-term imprisonment with or without hard labour. Local sentences were always more common than sentences of penal servitude.

The first directors of convict prisons appointed by the lord lieutenant were chairman Captain Walter Crofton, a retired Royal Artillery captain and magistrate in Wiltshire, who at thirty-nine years of age was the youngest of the three.Footnote 47 Captain Charles Raleigh Knight was formerly the governor of Portsmouth Prison and the governor of Canadian military prisons, while Irish-born John Lentaigne, a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, previously held various management positions such as the governor of Richmond District Lunatic Asylum, the vice-chairman of the South Dublin Union, and the high sheriff in Monaghan.Footnote 48 Crofton and Knight had been members of a commission to investigate Irish prisons a year prior to their appointment and would have had some knowledge of the strains under which the system was then operating. Now responsible for a prison system with in excess of 1,000 convicts beyond capacity, and new convictions expected, they set about determining who, under the change from transportation to penal servitude, had already served their time and could be discharged.Footnote 49 Other ‘insurmountable difficulties’ facing the directors included poorly designed or dilapidated prisons and inefficient or corrupt staff.Footnote 50

Tim Carey describes the Irish Convict System subsequently put into place, also known as the Crofton System after its creator, as ‘the single most important Irish contribution to penal history’.Footnote 51 The Crofton System was considered pioneering at the time and has been shown to have had significant international influence.Footnote 52 Carpenter considered in 1862 that the ‘closer the scrutiny, the deeper has been the conviction formed, that the “Irish Convict System” has solved the grand and difficult problem of combining the reformation with the punishment of the offender’.Footnote 53 The National Association for the Promotion of Social Science (NAPSS) judged Crofton’s system ‘the best system ever tried’.Footnote 54 In 1860 Prussian jurist Baron Franz von Holtzendorff considered that the intermediate stage of the system, the period between the convict prison and release whereby a convict was given more freedom than in prison, was a unique feature of the system, as was the intensity of police surveillance post release.Footnote 55 Carroll-Burke has identified other interconnected features that were novel or had up to that point only been attempted on a small scale, such as the system of convicts earning marks and progressing through various classes, promotions based on good conduct, the use of work as a reward, and individualised treatment to support return to society.Footnote 56 He concluded from his close assessment that the Irish Convict System was ‘both more penal and more therapeutic than the English system … it represented an expression of the pleasure-pain principle, deploying a double system of punishment-gratification, allowing both positive and negative reinforcement of desirable behaviour’.Footnote 57 But it did not receive universal accolade and debates abounded as to whether Crofton appropriately credited the British, Australian and other models on which he had based his system and whether it was as unique and effective as thought.Footnote 58 Crofton clashed in particular with Joshua Jebb, his equivalent in England, ‘stung by suggestions that he had overlooked ideas of value to the English system’.Footnote 59

While dramatic reductions in convict numbers brought initial optimism, it was not to last.Footnote 60 The directors limped on until the General Prisons (Ireland) Act, 1877, established the General Prisons Board (GPB), which remained in place until 1928, to manage Ireland’s four convict prisons, thirty-eight local prisons and ninety-five bridewells.Footnote 61 By this stage 1,114 convicts were in custody along with 2,817 prisoners in county gaols and 4,830 in bridewells.Footnote 62 Crofton, who had resigned due to ill health in 1862, made a brief return to senior management along with Charles Bourke, Captain John Barlow, who had been a prison inspector and then convict director since the 1860s, and Lentaigne as an unpaid member.Footnote 63 William Patrick O’Brien was appointed following Crofton’s resignation in October 1878. Crofton observed a ‘mischievous diminution of the directing power of the convict prisons’Footnote 64 across these years and by the early 1880s Irish convict prison rules were broadly in line with those in England.Footnote 65 Sr Magdalen Kirwan, manager of Goldenbridge Refuge until she became mother superior at the Baggot Street Sisters of Mercy Convent, alluded to this contemporary disillusionment when she commented to a royal commission in the early 1880s that she had been ‘very little in prisons since Sir Walter Crofton went away. I used to go into them very much in his time, and we used to talk over these things. Latterly the interest for convicts and prisons has, with many, passed away.’Footnote 66

That Ireland was under British rule during this period raises inevitable questions about the extent to which the Irish prison was a colonising site where British ideas were imposed on misbehaving locals. Several directors who headed the prison board were British born or had worked there for some time. They sat at Dublin Castle, the headquarters of British rule in Ireland, and reported to the lord lieutenant, the crown representative. But it is important not to impose binaries like coloniser and colonised in an Irish penal context.Footnote 67 Developments in Ireland had their roots in convict systems and female factories in Australia during the period of transportation. British penal reformers also frequently called for aspects of Crofton’s Irish Convict System to be extended there, and women headed Irish female prisons and held superior positions before this was the norm in England.Footnote 68 No doubt ideas about ethnicity shaped penal reformers’ attitudes and prison regulations, but these are difficult to isolate in an Irish female convict prison context given that ethnicity is an ‘articulated category’ interwoven with ideas about gender and class.Footnote 69 The Irish prison seemed to offer an opportunity to impose middle-class beliefs about appropriate behaviour on a group of predominantly lower-class individuals.

The Female Convict System

In 1825 influential prison reformer Elizabeth Fry called for a distinctive women’s prison system.Footnote 70 Grangegorman Female Penitentiary in Dublin became the first singularly female prison in the British and Irish Isles in 1836, under Marian Rawlins, selected by Fry because of her experience at Coldbath Fields Prison.Footnote 71 It housed prisoners and those awaiting transportation. The Freeman’s Journal reported on Grangegorman a couple of years later that the ‘experiment of an exclusive female prison was a new and a bold one, and the success of that experiment … was a triumphant argument of the truth of the opinions held on the subject’.Footnote 72 When the delegation sent to investigate Irish prisons visited Grangegorman in December 1853, they found around 260 female prisoners accommodated in only sixty-five cells, although ‘the prisoners, notwithstanding the adverse circumstances in which they are placed, present a singularly healthy appearance’.Footnote 73 The governor of the prison, Thomas Synnott, complained that there were ‘neither reception nor punishment cells, no baths, or the ordinary convenience for personal cleanliness; neither kitchen nor stores’.Footnote 74 The delegation recommended the discontinuation of Grangegorman and the establishment of a new female convict prison, separate to the male prison at Mountjoy.Footnote 75

In the interim, female convict numbers continued to rise. In 1854, Cork Female Convict Depot opened in the old Cork lunatic asylum building, under head matron Delia Lidwill.Footnote 76 Ninety convicts were transferred to the rented accommodation from Dublin across October and November, but the temporary Cork depot ultimately proved insufficient for the rising female convict population.Footnote 77 In February 1857 the sixty-two cells of Newgate Auxiliary Prison, a former male prison, became home to female convicts from county gaols.Footnote 78 It was anticipated that until the completion of the women’s prison at Mountjoy, convicts would undergo the probationary part of their sentences at Cork or Newgate before being transferred to Grangegorman to serve the remainder.Footnote 79

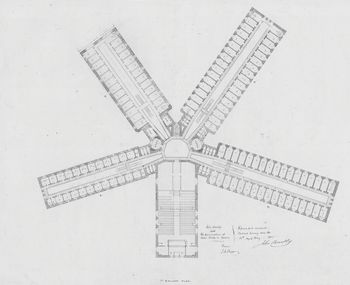

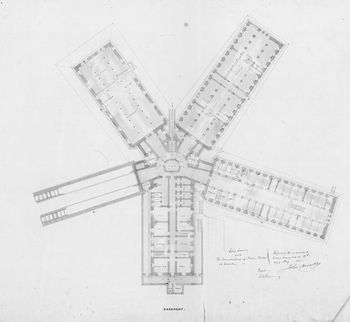

Mountjoy Female Convict Prison, designed by James Higgins Owen, architect to the Board of Public Works, received its first prisoner in September 1858.Footnote 80 The building of the prison already on the site had been supervised by Owen’s father, Jacob, who had held the position before him.Footnote 81 Over the course of the next three days, women and their children followed from Cork, Newgate and Grangegorman, despite the fact that, according to Delia Lidwill, who moved from Cork to become the superintendent at Mountjoy, it was ‘in a very unfinished state’.Footnote 82 The four-floor prison, in keeping with ideas at the time about surveillance, had five wings, four labelled A–D with 450 individual cells and a fifth with shared staff accommodation on the ground floor and the chapel and church above (Figure 0.1). It could accommodate 400 inmates across individual cells and shared dormitories.Footnote 83 A long corridor between wings B and C on the ground floor later led to the execution chamber, the laundry and the baths. The basement housed workrooms, stores and punishment cells for those inmates who broke prison rules (Figure 0.2). By 1871, the number of cells had increased to almost 500.Footnote 84

Figure 0.1 First floor plan of Mountjoy Female Convict Prison, 1855–8

Figure 0.2 Basement plan of Mountjoy Female Convict Prison, 1855–8

Although William Maturin, the Protestant chaplain at Grangegorman, recognised that the prospect of moving had unsettled prisoners, several factors meant that this was followed by a period of stability.Footnote 85 Firstly, Lidwill, already experienced in the management of convicted women, remained superintendent at Mountjoy for the next eighteen years, until her resignation and replacement by Anne Sheeran in 1876. Secondly, the female convict cohort was not again separated across multiple prisons for the remainder of the century, which facilitated the implementation of uniform practices and policies that had been difficult when they had been divided across three convict prison sites. Thirdly, for the next twenty-five years, all of Ireland’s convict women served time in Mountjoy Female Convict Prison, managed by women and in a separate building to male prisoners. Unlike male convicts in Ireland and female convicts in England at this time who moved sites as they progressed through the different stages of their respective penal systems, Irish convicted women were accommodated in the same building until discharge, unless eligible for transfer to a refuge to serve the final part of their sentences.Footnote 86 While the convict cohort in prison was not again divided for the remainder of the century, facilitating this analysis of experiences that is not possible for other countries, they did eventually move buildings. In 1883, Spike Island, a male convict site, closed and the two prisons on the Mountjoy complex were designated for men.Footnote 87 Across 5–6 June 1883, women were transferred to Grangegorman Female Prison, which now housed local and convict prisoners under superintendent Eliza Rothe until her retirement in January 1890 after thirty-three years in the prison system.Footnote 88 She was replaced after an interlude without a female head by thirty-one-year-old Catharine Julia McCarthy, selected from the English prison system for the role.Footnote 89 Fourteen years later, in August 1897, women were moved from Grangegorman to two wings of Mountjoy because of an urgent request for accommodation from the overcrowded Richmond District Lunatic Asylum.Footnote 90 The development of women’s prisons in North America and elsewhere was heavily influenced by events in Ireland.Footnote 91 Penologist Charles Coffin, who visited Mountjoy from the United States with his wife, Rhoda, in November 1871, concluded: ‘Two things are thoroughly demonstrated by this Institution – viz – the ability of women to conduct, govern and manage a prison for their own sex – and the power to reform many probably most of those committed.’Footnote 92 For both men and women in Ireland, expectations of gender affected incarcerated experiences, which are explored in the next five chapters.

The Numbers

The women featured in this book were exceptional in having been found guilty of a crime. In 1858 around one woman in every 4,000 was convicted of criminality.Footnote 93 Incarcerated women were fewer than men. In 1855 26,653 males and 21,793 females were committed to Irish local or convict prisons.Footnote 94 Sentences of penal servitude were even more atypical; in that year 299 males and 170 females were sentenced to transportation or penal servitude, representing 1.12 per cent and 0.78 per cent of total annual committals respectively.Footnote 95 As was the norm outside Ireland, the number of women in the convict system remained consistently below the male average throughout this period.Footnote 96 Women tended to be less visible in criminal activity and also likely to be punished less severely than men with local rather than convict prison sentences.Footnote 97 Ten years later, in 1865, the convict population comprised 486 women (28.6 per cent) and 1,213 men (71.4 per cent).Footnote 98

A decline in female and male criminal committals is evident across the latter half of the nineteenth century. In 1854 60,445 committals and a daily average of around 5,700 inmates equated to a rate of 93 committals per 100,000 population.Footnote 99 By 1900 the figures had decreased to 32,294 committals, a daily average of 2,398 inmates and a rate of 54 penal committals per 100,000 population.Footnote 100 The annual number of convicts in custody also decreased as the nineteenth century progressed from a total of 3,427 on 1 January 1855 to 329 on the same date in 1900.Footnote 101 The number of male convicts in custody declined by more than 91 per cent from 3,097 on 1 January 1855 to 277 on the same date in 1901 while the corresponding female convict population shrank by more than 95.4 per cent from 330 to a low of 15 (Table 0.1).Footnote 102 The female convict population peaked at 674 at the end of 1857. A decline in convictions does not necessarily mean a similar decrease in crime, dependant as the former is on the reporting of crimes to the police, police coverage and successes in apprehensions, guilty verdicts in court, legislation, the propensity of judges to opt for sentences of penal servitude, data gathering and other related factors.Footnote 103 However, the decrease in convictions, recognised as ‘very remarkable’ by GPB members, demands exploration.Footnote 104

Table 0.1 Irish female convict prison populations as at 31 December, 1854–1900

| Year | Cork | Grangegorman | Newgate | Mountjoy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1854 | 90 | 240 | ||

| 1855 | 360 | 259 | ||

| 1856 | 442 | 201 | ||

| 1857 | 419 | 193 | 62 | |

| 1858 | 77 | 411 | ||

| 1859 | 444 | |||

| 1860 | 416 | |||

| 1861 | 381 | |||

| 1862 | 437 | |||

| 1863 | 471 | |||

| 1864 | 504 | |||

| 1865 | 479 | |||

| 1866 | 436 | |||

| 1867 | 419 | |||

| 1868 | 403 | |||

| 1869 | 352 | |||

| 1870 | 333 | |||

| 1871 | 323 | |||

| 1872 | 310 | |||

| 1873 | 289 | |||

| 1874 | 281 | |||

| 1875 | 281 | |||

| 1876 | 263 | |||

| 1877 | 238 | |||

| 1878 | 212 | |||

| 1879* | 202 | |||

| 1880* | 163 | |||

| 1881* | 139 | |||

| 1882* | 108 | |||

| 1883* | 101 | |||

| 1884* | 88 | |||

| 1885* | 81 | |||

| 1886* | 82 | |||

| 1887* | 61 | |||

| 1888* | 51 | |||

| 1889* | 41 | |||

| 1890* | 30 | |||

| 1891* | 26 | |||

| 1892* | 37 | |||

| 1893* | 35 | |||

| 1894* | 41 | |||

| 1895 | 30 | |||

| 1896 | 37 | |||

| 1897 | 32 | |||

| 1898 | 19 | |||

| 1899 | 20 | |||

| 1900 | 15 |

* Figures for these years are as at 31 March.

Numbers in custody reflect societal, economic and legislative circumstances at the time of conviction. Ireland witnessed dramatic population decline from 6,552,385 in 1851 to 4,458,775 in 1901, which undoubtedly impacted committal figures.Footnote 105 As mentioned earlier in this introduction, high imprisonment in the 1850s has been attributed to the Great Famine that ‘commenced to swell the amount of our criminal population’, and the Vagrancy (Ireland) Act in 1847.Footnote 106 By the late 1850s the tragic decrease in population due to deaths and diseases in the previous decade had relieved pressure on resources and prison numbers stabilised. The post-Famine period also witnessed economic growth, although food and fuel shortages in the late 1870s and early 1880s brought further poverty.Footnote 107 In 1860 and 1870 daily averages equated to rates of 43 and 42 committals per 100,000 population, respectively.Footnote 108

Legislative changes also impacted annual figures. The Penal Servitude Act, 1853, legislated for a minimum penal servitude sentence of four years, reduced to three in 1857.Footnote 109 Delia Lidwill, superintendent at Mountjoy Female Convict Prison, complained:

[S]hort terms can effect very little for the reformation of prisoners. … a long sentence helps to wean her from the evil associations to which she may have been exposed, – it gives her time for reflection upon the folly and wickedness of her past life, and more thoroughly accustoms her to the good habits enforced by prison restraint.Footnote 110

Lidwill must thus have been pleased that the subsequent Penal Servitude Act, 1864, imposed a minimum sentence of five years. Twenty-eight-year-old Bridget Brien, sentenced to three years of penal servitude for breaking into a shop and stealing therefrom in Waterford on 19 July 1864, received the minimum sentence that was two years less than that received by twenty-eight-year-old Ellen Hennessy, convicted of larceny in Galway one week later.Footnote 111 This act also introduced a seven-year minimum sentence for women who had previously spent time in penal servitude. A woman’s criminal history rather than the circumstances of her crime thus determined her sentence and meant a prolonged presence in the prison and numeration in successive annual returns. This act was eventually repealed by the Prevention of Crime Act, 1879, and is explored in Chapter 5.Footnote 112

Although optimism permeated the early years of the female convict system, the view that inmates could be ‘cured’ of criminal tendencies through serving long periods of imprisonment held less sway by the end of the century. Church of Ireland chaplain Henry Hogan explained in 1891: ‘Everything is done, that is possible under the prison system, by gentle discipline, religious ministrations, and by the kindness and attention of the officers, but … I fail to see, after an experience of many years, any good end served by long periods spent in prison.’Footnote 113 Changing minimum sentences and attitudes towards custodial sentences also coloured judges’ and jurors’ views and influenced verdicts and subsequent prison numbers. Some judges may have been more inclined to push for guilty verdicts in the aftermath of transportation, knowing that convicted women would not be sent thousands of miles from their families. Likewise, the introduction of a minimum sentence of five years possibly encouraged some judges to opt instead for shorter sentences of imprisonment rather than penal servitude. When Sr Magdalen Kirwan, manager of Goldenbridge Refuge, was asked for her opinion, she mused: ‘I think that the judges have an idea that it is not right to give a woman such a long sentence as they would give a man. There is a sort of false feeling, I think about giving women long sentences.’Footnote 114 Sentences thus reflect judges’ opinions as to the effectiveness or appropriateness of penal servitude and towards the end of the century preference was for local prison sentences. The Penal Servitude Act, 1891, restored the three-year minimum penal servitude sentence.Footnote 115 This meant that fewer inmates were recorded in annual statistics in the 1890s than previously, not only because penal servitude sentences had become less common, but also because sentences were shorter and, therefore, numeration across consecutive annual reports fewer.Footnote 116

Scholars elsewhere have noticed similar declines in prison populations towards the end of the nineteenth century. Feeley and Little’s close reading of Old Bailey records from 1687 to 1912 reveals a striking decline in the number of women tried across the period. Connecting the micro to the macro, they point to ‘a period of shifting gender roles and controls’ whereby gendered expectations and more intense monitoring of women’s behaviour limited opportunities for criminality. They also point to the increased use of non-custodial sentences.Footnote 117 In France too O’Brien witnesses a decline in male and female central prison populations and attributes this to the increased use of non-custodial sentences.Footnote 118 In Ireland, the decline in prison populations in later years may also indicate a reliance on other institutions. After 1898, inebriate homes offered alternatives to incarceration in prison for those declared by the courts to be ‘habitual drunkards’ and were disproportionately women.Footnote 119 There is also evidence to indicate that courts directed women, particularly young or first-time offenders, to Magdalen asylums, a practice that seems to have become more commonplace in Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State after Irish independence in the early 1920s.Footnote 120

Writing the Prison: Historiography

Scholars have traced the historiography of prisons from their traditional interpretation as evidence of civilising progress and humanitarianism to revisionists, such as Michel Foucault and Michael Ignatieff, who saw prisons as a form of social control alongside other institutions.Footnote 121 Female prisoners were often excluded from such analyses.Footnote 122 Subsequent examinations of incarcerated women have highlighted how Foucault’s tendency to ignore gender concealed differences.Footnote 123 Estelle B. Freedman’s influential 1981 study of women’s prisons from 1830 to 1930 explores motivations and ethos behind their establishment, using inmate histories from the Reformatory Prison for Women at Sherborn, Massachusetts.Footnote 124 Nicole Hahn Rafter’s subsequent examination of state prisons that held women, predominantly in New York, Ohio and Tennessee from the late eighteenth century to 1935, outlines the origins of exclusively female state prisons and traces the growth of the movement that emphasised reform rather than punishment, as well as the development of parallel custodial prisons. Rafter agrees with Freedman that penal reformers were increasingly sympathetic to the ‘fallen woman’ but identifies that they regarded her as a victim rather than an agent. Rafter argues that ‘if the fallen woman was not a victimized “sister” but rather an autonomous, deliberately sexual being, then the raison d’etre of social feminists – their concept of womanliness and, with it, the justification for their work – was built on air’.Footnote 125 In 2006, L. Mara Dodge furthered our knowledge of nineteenth- and twentieth-century criminality and imprisonment in her detailed study of female incarceration in Illinois. She explores how factors such as age, race and class shaped arrests, prosecution and sentencing.Footnote 126

Although not solely a study of women, Patricia O’Brien’s 1982 examination of prisons for serious offenders in nineteenth-century France incorporates a gender analysis. She seeks to examine the prison ‘from the inside out’ given that inmates ‘continue to be discussed as undifferentiated, faceless masses’.Footnote 127 Lucia Zedner uses published reports, memoirs, contemporary literature and archival material in her comprehensive exploration of gendered responses to female criminality in nineteenth-century England and includes chapters on local as well as convict prisons.Footnote 128 Subsequent work by Neil Davie, Bill Forsythe, Barry Godfrey, Helen Johnston, Helen Rogers and Lucy Williams has furthered knowledge of aspects of British (especially English) prison life such as staff-inmate relationships, religion and education.Footnote 129 The Digital Panopticon project, which matched data on suspects tried in London across around fifty data sets, demonstrates how linking biographical details can reveal much about individuals and crime and punishment on a broader scale.Footnote 130

In 1990 Beverley Smith complained: ‘Whether transported felon, Fenian convict, or IRA hunger-striker, that figure [of the prisoner] has been almost always male.’Footnote 131 Criminal Irish women feature in studies of transportation. Research in the 1950s and 1960s on transportation to Australia was greatly aided by detailed record-keeping at home and abroad. Contemporary characterisations of female transportees as depraved and immoral, and paperwork documenting their transitions into and out of female factories for idleness, drunkenness or other perceived misbehaviour, served to focus debate on convict women’s sexuality.Footnote 132 In 1997 Oxley argued that associating sex work and poverty with morality rather than economics had done a disservice to the history of convict women and this ‘preference for passing judgement on morality and character has diverted analysis from the real issues of convict work and life’.Footnote 133 Scholarship from the 1970s by Leonora Irwin, Brenda Mooney, Deborah Oxley, Portia Robinson, John Williams and others offered a more nuanced understanding of transported convict women’s lives and experiences.Footnote 134 Williams found that Irish women differed to their English counterparts in that more were convicted outside towns. Irish women were mostly Catholic, more likely to be under the age of thirty and unmarried, and, although recidivism was common, fewer had previous convictions than English women (64 per cent compared to 70 per cent).Footnote 135 Oxley also notes differences between Irish and English female convict cohorts in New South Wales; Irish women were transported for vagrancy whereas English women were not, they were more likely than English women to be unable to read and write, they had a greater tendency to age heap than their English counterparts (suggesting a lack of knowledge of actual age), and fewer declared as skilled. She also demonstrates how the different national economies were reflected in slight variations in the nature of crimes.Footnote 136 Themes of assimilation abroad and background also continue to be explored in focused histories of Irish convict women.Footnote 137

In 1996 Oxley observed: ‘We know women were there, albeit in fewer numbers than men, but we do not know enough about what women did in the colony.’Footnote 138 Engaging social histories by Joy Damousi and Kirsty Reid greatly aid understandings of women’s lived experiences, the former in an exploration of imprisonment in New South Wales from the 1820s to the 1840s, and the latter in a detailed study of the convict workplace in Van Diemen’s Land.Footnote 139 Both Damousi and Reid explore workplace and prison resistance, complicating the narrative of women as victims. Reid considers that daily acts of resistance ‘were particularly potent weapons when deployed by domestic workers who could constantly disrupt household routine’.Footnote 140 Bláithnaid Nolan’s account of Irish women’s involvement in lesbian subcultures in Van Diemen’s Land female factories offers new insights into convict women’s relationships.Footnote 141 Social histories of transportation and incarceration experiences provide useful points of comparison for the Irish female convict prison context, and this study takes its cue from these works.

Imprisonment in Ireland has, until recently, been largely explored in a political context.Footnote 142 Constance Markievicz is one of the few women to feature in Sean McConville’s detailed examination of Irish political prisoners from 1848 to 1922.Footnote 143 William Murphy’s engaging account of political imprisonment from 1912 to 1921 opens with a discussion of the suffragettes.Footnote 144 Other important work on Irish women in the revolutionary period has similarly examined their imprisonment in Ireland and England.Footnote 145 Fascinating research by Niall Bergin and Laura McAtackney on graffiti at Kilmainham Gaol demonstrates the insights that can be gleaned from archaeological examinations.Footnote 146 Assessments of women’s incarceration has also focused on the Northern Irish Troubles.Footnote 147 The Irish convict prison is known to have had widespread influence, but it was not the subject of close historical research until Carroll-Burke’s interrogation in 2000. His study from above provides a detailed analysis of the development and progress of the system up to the 1860s, although it does not generally consider gender differences in detail.Footnote 148 Rena Lohan’s rich publications shed light on aspects of the Irish female convict prison at Mountjoy particularly relating to staff.Footnote 149 Her unpublished MLitt, largely a history from above that traces changes in policy and practice in the female convict prison system across the nineteenth century, remains the most comprehensive account of convict women’s incarceration in Ireland to date.Footnote 150 Using ethnographies, Christina Quinlan has written the first book-length study of Irish women’s imprisonment from a sociological and criminology perspective and, in one chapter, provides a historical overview across two centuries.Footnote 151 This important work offers a point of comparison to the past and demonstrates how societal attitudes towards criminal women impact experiences.

Maria Luddy’s meticulous work on nineteenth-century philanthropy includes consideration of middle-class and religious women’s roles in prison.Footnote 152 Imprisoned women also feature to different degrees in studies of single prisons, including Tim Carey’s detailed history of Mountjoy and Niamh O’Sullivan’s study of Kilmainham.Footnote 153 Geraldine Curtin’s richly illustrated account of Galway Jail offers an engaging insight into the backgrounds and crimes of women incarcerated in a local prison between 1878 and 1892.Footnote 154 The imprisonment experiences of other specific cohorts have also been explored. Frances Finnegan and Maria Luddy have considered the incarceration of women who worked in the sex industry.Footnote 155 Ciara Breathnach and Laurence M. Geary focus on forty convicts sentenced to penal servitude for agrarian offences in Munster in the early 1880s, while Conor Reidy and Paul Sargent have explored the treatment of juvenile offenders in Ireland.Footnote 156

Prisoners’ physical and biographical details continued to be recorded long after the introduction of photography to the female convict prison in 1866.Footnote 157 Detailed inmate records have facilitated quantitative assessments from medical, social and economic history approaches.Footnote 158 Matthias Blum, Chris Colvin, Laura McAtackney and Eoin McLaughlin have mined prison admission registers to advance our knowledge of age and education.Footnote 159 Ciara Breathnach and I have assessed descriptors of convicts’ bodies to study tattoos in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 160 Breathnach has also meticulously examined 251 male and female convicts’ medical records to offer an insight into health, diet and relationships between convicts and medical officers employed in the prison.Footnote 161 Ó Gráda has used height records from Clonmel Prison registers to consider health.Footnote 162 Catherine Cox and Hilary Marland have examined the mental and physical well-being of male and female criminals in local and convict prisons.Footnote 163 Additional outputs on this subject, emerging from their wide-ranging and exciting Wellcome-funded project, ‘Prisoners, medical care and entitlement to health in England and Ireland, 1850–2000’, will further our knowledge of medical treatment and mental and physical well-being behind bars.Footnote 164

The significant place of institutions in Irish nineteenth- and twentieth-century society has resulted in the publication of important studies from historical, sociological, criminological and economic perspectives, of so-called lunatic asylums, workhouses, industrial schools, reformatories, inebriate homes and Magdalen asylums.Footnote 165 Research that examines aspects of prison life in a wider institutional context, such as Ian Miller’s exploration of diet and food through institutional records, allows for comparative perspectives and facilitates an understanding of institutional norms.Footnote 166 Further research on occupants of institutions will shed greater light on the multitude of experiences, the impact of societal attitudes and developments across these facilities, and the extent of voluntary or forced movement of residents between various residences.

Reconstructing Convict Women’s Experiences: Historical Sources

Much of the evidence upon which this book is based is elicited from a close reading of inmates’ individual penal files. These records detail inmates’ biographies, physical measurements, crimes and criminal histories, rule breaches and punishments during incarceration, and discharge. From the 1880s penal files tended to include mugshots, details of medical care, lists of visitors, outgoing and incoming letters, dockets documenting misbehaviour and prisoners’ explanations for their actions, and correspondence between officials or others relevant to that inmate. Some files are significantly larger than others. Standardised penal forms that comprised blank spaces rather than tick-box categories relay a woman’s name, age, places of birth and residence, occupation, education, religion, marital status, location (and later name) of next of kin and information relevant to her crime and previous offences. Such categories reflect what officials considered important and could capture in the form.Footnote 167 Details of crime, sentence and dates of committal and conviction would have been compiled from the documents that accompanied each woman to the convict prison from the local gaol in which she had awaited trial and the court at which she had been tried.

Convicts were expected to provide additional details as necessary. Foucault considers that the registration of individuals in this manner was a form of control through knowledge.Footnote 168 Women seem to have been quite forthcoming with biographical information and self-reported their criminal histories. They may have assumed that such information was already known, or that falsehoods would be found out and punished.Footnote 169 Biographical information, Carolyn Steedman notes, ‘sometimes functions as compensation for not really knowing (or knowing that you will never really know) the “truth” of the people and events you write about’.Footnote 170 But details recorded in these forms sometimes prove inaccurate. Convicts may not have known the information requested of them or may have been hesitant to reveal details for various reasons. Margaret Brien was listed as an unmarried mother on admission to prison for larceny in Cork in 1858. When she was rejected from the religious-run refuge on this basis towards the end of her sentence, she admitted that she was married, which was verified by her marriage certificate located in Cork.Footnote 171 Other inmates provided misinformation in a deliberate effort to deceive the authorities. Twenty-three-year-old Bridget Carr seems to have acknowledged a previous offence on conviction for theft in 1876, but the information that she provided about her alias, crime, sentence and the place and date of conviction were later found to be incorrect.Footnote 172 Richard W. Ireland has concluded that a prisoner had ‘every incentive to conceal his [or her] real name, his [or her] previous record, and any information that could give clues as to these, such as place of birth or last residence’.Footnote 173 Prisoner details that should have remained consistent throughout a sentence or between sentences are also sometimes conflicting. Donegal convict Margaret Magee was released from custody twice, first on a conditional release to Goldenbridge Refuge in 1868 and subsequently, in 1869, from the convict prison to which she had been returned because of misbehaviour at Goldenbridge. Her 1868 file notes Fermanagh as her place of birth while the later form lists her birthplace as Tyrone.Footnote 174 Information was often copied verbatim from previous forms even when details would have changed in the interim. Margaret Broughan was documented as being fifty-six years of age on conviction for being in possession of base coin in 1871 and theft of a dress in 1877. The governor who recorded her age in 1877 acknowledged that the information was out of date but did not amend it.Footnote 175

Although they were compiled for official purposes, penal files offer tantalising glimpses of prison life and experiences in the nineteenth century, including, for instance, exchange networks, complexities of relationships and leisure pursuits that prisoners forged for themselves from the daily routine. The ‘dilemma of plenitude’ also proves challenging.Footnote 176 Iacovetta and Mitchinson ask: ‘How do we generalize or make comparisons among cases when every story is in some respects unique?’Footnote 177 Each of the thousands of prison files examined for this study was used to build a database repeating categories from penal files in order to facilitate analyses of the general picture as well as change in prisoner profiles over time. In this manner penal files are used both quantitatively, particularly in the five case studies that precede each chapter, and qualitatively. The database includes those sentenced to transportation who were instead accommodated in the convict prison after 1854, as well as those who were convicted in the nineteenth century but released after 1900. It counts admissions rather than inmates because recidivists cannot always be connected to their prior offences. Many women had multiple aliases and regularly provided different forenames or surnames. Their propensity to change their names on marriage also rendered it difficult for authorities, and subsequently the historian, to match individuals to their previous corresponding criminal convictions.Footnote 178 It is likely that some repeat offenders evaded both.

In her key work on women’s imprisonment in the United States, Freedman has identified that the ‘most difficult problem in prison history is reconstructing the inmate experience’.Footnote 179 Stated prison rules might not have been followed, abuses might not have been documented, and changes in practices often prove difficult to date. Convicts could, for example, complain of treatment to members of prison visiting committees, appointed by lords lieutenant and generally comprising powerful men such as magistrates and politicians.Footnote 180 In addition to differences in power and gender that might have rendered such visitors unlikely to take certain complaints seriously or some imprisoned women reluctant to complain, Mountjoy Female Convict Prison was not visited at all in 1880 or 1881 and only once in 1882. Complaints may thus have gone unheard or unrecorded.Footnote 181 Annual reports required of the prison board, published as parliamentary papers, are used extensively here and generally include accounts from the superintendent, religious chaplains, schoolmistress and medical officer of the prison.Footnote 182 These reports provide valuable quantitative overviews of multiple institutions and inmates in a given year and offer an insight into the views of those in positions of power. But draft reports are known to have been reviewed by prison board members prior to publication.Footnote 183 From the late 1870s these reports also became less anecdotal, partly limiting their usefulness for an understanding of convict experiences. These records have been supplemented by prison correspondence, which offers insight into the day-to-day running of the prison and the women incarcerated therein.

Given contemporary interest in penal developments, the Irish Convict System and Mountjoy’s international reputation as a leading penal institution, particularly in the 1860s, it is unsurprising that the prison featured in published accounts of visits to Ireland. A writer in 1865 acknowledged: ‘Few travellers from any land whose thoughts have ever been directed to the consideration of questions of punishment and reformation, fail to visit the Mountjoy Female Convict Prison, when they find themselves within a journey of a day or so from Dublin.’Footnote 184 These contemporary accounts offer useful comparative perspectives and observations of space, individuals and practices in the women’s convict prison, albeit usually drawn from a single, chaperoned visit when direct interaction was with staff rather than inmates. Such accounts are also revealing of wider attitudes towards women, criminality and imprisonment more generally.

Virginia Crossman describes as faint but present the voices of the poor in records relating to the Irish Poor Law.Footnote 185 In the prison too faint voices and personalities of prisoners emerge from individual files, with the caveat that inmates did not construct their own penal files and their voices, when recorded, are generally preserved in writing by officials. These records are supplemented by convict petitions, usually submitted, sometimes in the prisoner’s own hand, as an attempt to secure early discharge or a commutation of sentence. Other petitions were written by relatives or professionals. Esther Alcock explained in 1861 that a petition submitted on behalf of her incarcerated daughter ‘was drafted by a Lady’ and subsequently copied by a male scribe.Footnote 186 These petitions have been used well by scholars because they are rich in first-hand detail about the crimes, motivations and responses, as well as plans for the future, albeit tailored to evoke the lord lieutenant’s sympathy.Footnote 187 In that respect they differ from letters, but between the formulaic sentences we can gain some sense of how actions and court proceedings were understood and how prison life was directly or indirectly experienced. The practice of referring petitions to the judges before whom cases were tried for their accounts or views, or to policemen or other authority figures who had known the petitioner prior to conviction, resulted in the generation of additional, rich evidence.Footnote 188

Additionally, among the records, filed in individual penal files with convict petitions or among prison department correspondence, are intimate letters written to incarcerated women by their relatives and friends, or by imprisoned women to their loved ones or to prison officials after release. The significance of emigration from Ireland has meant that historical research on migrant letters has been a strong feature of Irish historiography since the 1980s.Footnote 189 Between 1801 and 1921, at least 8 million inhabitants left Ireland and, unusually for emigration practices, almost half were female.Footnote 190 In recent years, scholarship on so-called begging or charity letters has further enriched our understanding of ways that inhabitants understood, narrated or negotiated their own poverty-stricken experiences. Emerging work on this subject in an Irish context has been led by Virginia Crossman and Lindsey Earner-Byrne.Footnote 191 But while these excellent studies examine Dublin-based funds that largely attracted Dublin-based writers, letters used in this book originated from all over Ireland (and sometimes beyond) precisely because the convict prison housed all of the island’s convict women.

Inconsistent spelling or grammar or the tendency of some writers not to punctuate (copied verbatim in this book) allude to pronunciation or regional dialect and oral influences, as well as the lack of formal education beyond the primary level. Surviving documents were not penned by the uneducated or inexperienced, and frequently demonstrate a clear awareness of contemporary letter-writing conventions.Footnote 192 The state-funded national education system introduced in Ireland in 1831 (and rendered compulsory from 1892), as well as years in the convict prison system, improved literacy abilities.Footnote 193 Some outgoing or incoming letters would also have been written on behalf of rather than by the signatory, but, as King reminds us, this ‘does not mean that the sentiments, experiences and rhetoric built into the infrastructure of the letters bear little resemblance to those of the paupers who were the subject of them’.Footnote 194 The scrawled notes or carefully penned scripts in prison records capture on paper the voices of those directly or indirectly affected by conviction or incarceration. They convey urgency, desperation and heartbreak and, like begging letters, frequently portray ‘narratives of need’.Footnote 195 These letters, although not extant for most incarcerated women, offer glimpses of their lives that they wanted to narrate after liberation, and their hopes for the future. Crossman recognises the value of such first-hand accounts as ‘unmistakeable’.Footnote 196 Through this multitude of rich and fascinating sources, coupled with newspapers, we can gain a unique insight into how incarcerated women experienced prison life, how they loved and lived, and how they and their relatives navigated difficulties and challenges outside prison.

Carolyn Steedman has described Archive Fever, which ‘comes on at night, long after the archive has shut for the day’. It begins ‘in the bed of a cheap hotel, where the historian cannot get to sleep. … This symptom – worrying about the bed – is a screen anxiety. What keeps you awake … is actually the archive, and its myriads of the dead, who all day long, have pressed their concerns upon you.’Footnote 197 The hospitality of friends and relatives alleviated concerns about accommodation during the course of this research, but I spent much time worrying about the women whose lives are recorded in prison files, their daily activities documented for a few years precisely because they were convicted of a crime deemed to warrant a lengthy prison stay. There seems a responsibility attached to working with these records, to do these women justice, to do their victims justice, to convey the complex realities of their lives and the society in which they lived. Individual stories and individual women thus have a central place in this book. Taking its cue from Heather Ann Thompson, each chapter is also preceded by a detailed case study that offers an insight into a woman’s life as revealed by historical records and, in four of the five cases that focus on prisoners rather than staff, criminal convictions.Footnote 198 The protagonist or protagonists of each of these five studies are contextualised in relation to a different theme, namely the crime, marital and parental status, age, class and occupation, or regionality. These examples shed much light on lived realities in wider nineteenth-century Irish society and enrich our understanding of criminality and punishment. Their stories are used here to build a social history of life in the nineteenth-century Irish female convict prison.