It has long been argued that democratic regimes and public support for them are mutually reinforcing: that high levels of public support ensure democracies remain strong and that experience with democratic governance generates robust public support (see, e.g., Easton Reference Easton1965; Lipset Reference Lipset1959). But the evidence for either part of this claim has been decidedly mixed. Countries with greater democratic support have been found to become stronger and more stable democracies (e.g., Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005, 251–4) and just the opposite (Fails and Pierce Reference Fails and Pierce2010, 182–3). Similarly, studies have alternately found that more experience with democracy yields more democratic support (e.g., Fails and Pierce Reference Fails and Pierce2010, 183) or instead that long-established democracies are suffering from democratic fatigue (e.g., Foa and Mounk Reference Foa and Mounk2017).

One important reason for these mixed results is the difficulty of measuring democratic support over time and across many countries. Public support for democracy cannot be directly observed, and its incorrect measurement will limit inferences about the relationships between public opinion and institutional development. Furthermore, the survey data available across countries and over time on support for democracy—or indeed most topics in public opinion—are sparse and incomparable, greatly hindering broadly comparative research. Recent pioneering studies have sought to overcome the hurdle of sparse and incomparable data by developing latent variable measurement models of public opinion (see Caughey, O’Grady, and Warshaw Reference Caughey, O’Grady and Warshaw2019; Claassen Reference Claassen2019; Solt Reference Solt2020). A pair of prominent recent works took advantage of this latent variable approach to measure democratic support for over one hundred countries for up to nearly three decades and assess, respectively, its consequences for and roots in democratic change (Claassen Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b). The first of these works concluded, supporting the classic argument, that mass support had a positive influence on democratic change, especially the endurance of democracy (Claassen Reference Claassen2020a, 127–30). The second directly contradicted the classic argument, concluding that democratic change has a thermostatic effect on public support—that is, that rather than generating its own support, deepening democracy provokes a backlash and it is instead democratic backsliding that calls forth greater public support (Claassen Reference Claassen2020b, 46–50).

The models employed in these studies’ analyses, though, do not account for uncertainty in their measurement of democratic support. Because they are unobserved, latent variables are inherently accompanied by measurement uncertainty. To leave this uncertainty unacknowledged is to make the implausible assumption that the latent variables are measured perfectly, an assumption that distorts both statistical and substantive inference (see, e.g., Crabtree and Fariss Reference Crabtree and Fariss2015).

Here, we reexamine the classic arguments about support for democracy and democratic change that were tested in these two pieces while correcting this oversight. In addition to incorporating the measurement uncertainty, we sought to reduce it by expanding considerably the survey data drawn on and reestimating democratic support for 144 countries for up to 33 years between 1988 and 2020. Our analyses reveal that the significant relationships between public support and democratic change disappear once measurement uncertainty is taken into account, both in replications with the studies’ original data and in our extension analyses that incorporate additional data. That is, simply taking into account measurement uncertainty—making no change to the specification of the models—reveals there is no empirical support for either claim put forward in these two works: declining democratic support does not signal subsequent democratic backsliding, and changes in democracy do not spur a thermostatic response in democratic support.

There are several important implications of these null results. They point to a need for closer attention to the conditional aspects of the classic theory (see Easton Reference Easton1965, 119–20; Lipset Reference Lipset1959, 86–9). On the one hand, the effect of democracy on public support may depend not on its mere existence but on its effectiveness (see Magalhães Reference Magalhães2014), particularly with respect to redistribution (see Krieckhaus et al. Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014). On the other, the influence of public support on democracy may depend on the extent to which those who support democracy are also dissatisfied with the current regime’s performance (see Qi and Shin Reference Qi and Shin2011). Similarly, the results presented here are further evidence that the survey items that are commonly employed to measure democratic support are inadequate for the task. Because these questions contain no information on respondents’ support for democracy relative to other values with which it may come into conflict (see, e.g., Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Simonovits, McCoy, and Littvay Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022) or on whether respondents even understand the meaning of the democracy they are claiming to support (see, e.g., Kirsch and Welzel Reference Kirsch and Welzel2019; Wuttke, Gavras, and Schoen Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2020), these questions appear to miss capturing the true extent of the support among the public that democracy will actually find when public support is in fact most needed. Our results also reinforce arguments that relationships between democracy and public support unfold only over the long term (see, e.g., Welzel, Inglehart, and Kruse Reference Welzel, Inglehart and Kruse2017) and that democratic change in the short term is instead best understood as an elite-driven phenomenon (see, e.g., Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2021).

We draw two conclusions, one methodological and one substantive. Many constructs in social science—from democracy to corruption to public opinion—are latent variables, and recent advances have made estimating them much more practicable. As latent variable measurement models become more commonly used, it is absolutely necessary for researchers who use them to incorporate the associated uncertainty into their analyses. As demonstrated here, this can be done straightforwardly using the method of composition (see Tanner Reference Tanner1993, 52; Treier and Jackman Reference Treier and Jackman2008, 215) without requiring any further change in model specification.

And, at a time when democracy is seen as under threat around the world (e.g., Diamond Reference Diamond2015), taken together, Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b) sends what is ultimately a reassuring message: the fate of democracy rests with us, the public, and when democratic institutions are undermined, we will swing to their support and constitute “an obstacle to democratic backsliding” (Claassen Reference Claassen2020b, 51). Both of these assertions may well be true, but the evidence we have, properly assessed, does not support them. There is no room for complacency.

Method

We proceed in three steps.Footnote 1 First, we reproduce the original analyses of Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b), which included only the point estimates of the latent variable of democratic support and so exclude its measurement uncertainty. Second, we collect the original cross-national survey data, replicate the latent variable measure of democratic support used in the two articles, and conduct the articles’ analyses again, this time maintaining the entire distribution of estimates of democratic support in each country-year.Footnote 2 As democracy is also a latent variable in these analyses, we include the quantified uncertainty in its estimates as well, along with that for corruption in the models of Claassen (Reference Claassen2020b).Footnote 3 In the third step, we collect even more survey data—increasing these source data by one-third—and reestimate the two articles’ analyses once more, again maintaining the full distribution of estimates to preserve measurement uncertainty.Footnote 4

Incorporating Uncertainty

Although measurement uncertainty has not yet attracted attention in the field of comparative public opinion, latent variables are always estimated with a quantifiable amount of measurement error, and ignoring measurement error in analyses can attenuate, exaggerate, or even reverse coefficient estimates as well as bias standard errors (see, e.g., Bound, Brown, and Mathiowetz Reference Bound, Brown, Mathiowetz, Heckman and Leamer2001, 3709; Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018, 254). In light of this, recent studies measuring other latent variables have recommended incorporating their measurement uncertainty in analyses (see Gandhi and Sumner Reference Gandhi and Sumner2020, 1553; Solis and Waggoner Reference Solis and Waggoner2021, 18) and research examining the consequences of public opinion in the United States has done so (see, e.g., Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018, 254; Kastellec et al. Reference Kastellec, Lax, Malecki and Phillips2015, 791–2). Therefore, after replicating the original analyses that use only the point estimates for public support and the other variables included in the model, we perform the analyses again only this time incorporating uncertainty in the articles’ models using our replicated data. We conduct inferences from the distributive data via the technique known as the “method of composition” (MOC; Tanner Reference Tanner1993, 52). MOC accounts for uncertainty from opinion estimates and analysis models through each modeling stage. In the analysis stage, uncertainty is incorporated through simulation based on the variance–covariance matrix of a model without requiring any change to its specification. This allows MOC to be broadly applicable to many different types of models, including time-series cross-sectional models (Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018, A15–16), Cox proportional hazards models (Treier and Jackman Reference Treier and Jackman2008, 215), or models of individual-level roll-call voting (Kastellec et al. Reference Kastellec, Lax, Malecki and Phillips2015, 791).Footnote 5

Adding More Data

To provide a further test of the classic arguments on democracy and public support, we generated estimates of democratic support using the same procedure as in Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b) on a bigger dataset, assembling as much survey data on democratic support as possible. We employed 4,905 national opinions on democracy from 1,889 national surveys, representing a 32.0% and 37.3% increase respectively over the 3,716 opinions and 1,376 national surveys used in Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b).Footnote 6

Results

Figure 1 presents the reanalyses of the hypothesis that public support influences the level of democracy (Claassen Reference Claassen2020a, Table 1). The lighter, left-hand set of results replicates the analysis of Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a), including its exclusion of measurement uncertainty by using only the point estimates of public democratic support and the other variables measured with quantified error (i.e., democracy and corruption), and they reproduce that article’s findings. The middle results introduce a single change: the uncertainty in the measurement of public support and these other variables is taken into account. In all four models, the positive coefficients for democratic support are no longer statistically significant. The darker, right-hand results also incorporate uncertainty but additionally replace the estimates of democratic support with those based on our expanded dataset; this change works to increase the number of observations analyzed as well. Although the confidence intervals shrink considerably, the coefficient estimates move much closer to zero: the hypothesis remains unsupported.

Figure 1. The Effect of Public Support on Democracy with Uncertainty

Note: Replications of Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a), Table 1, 128.

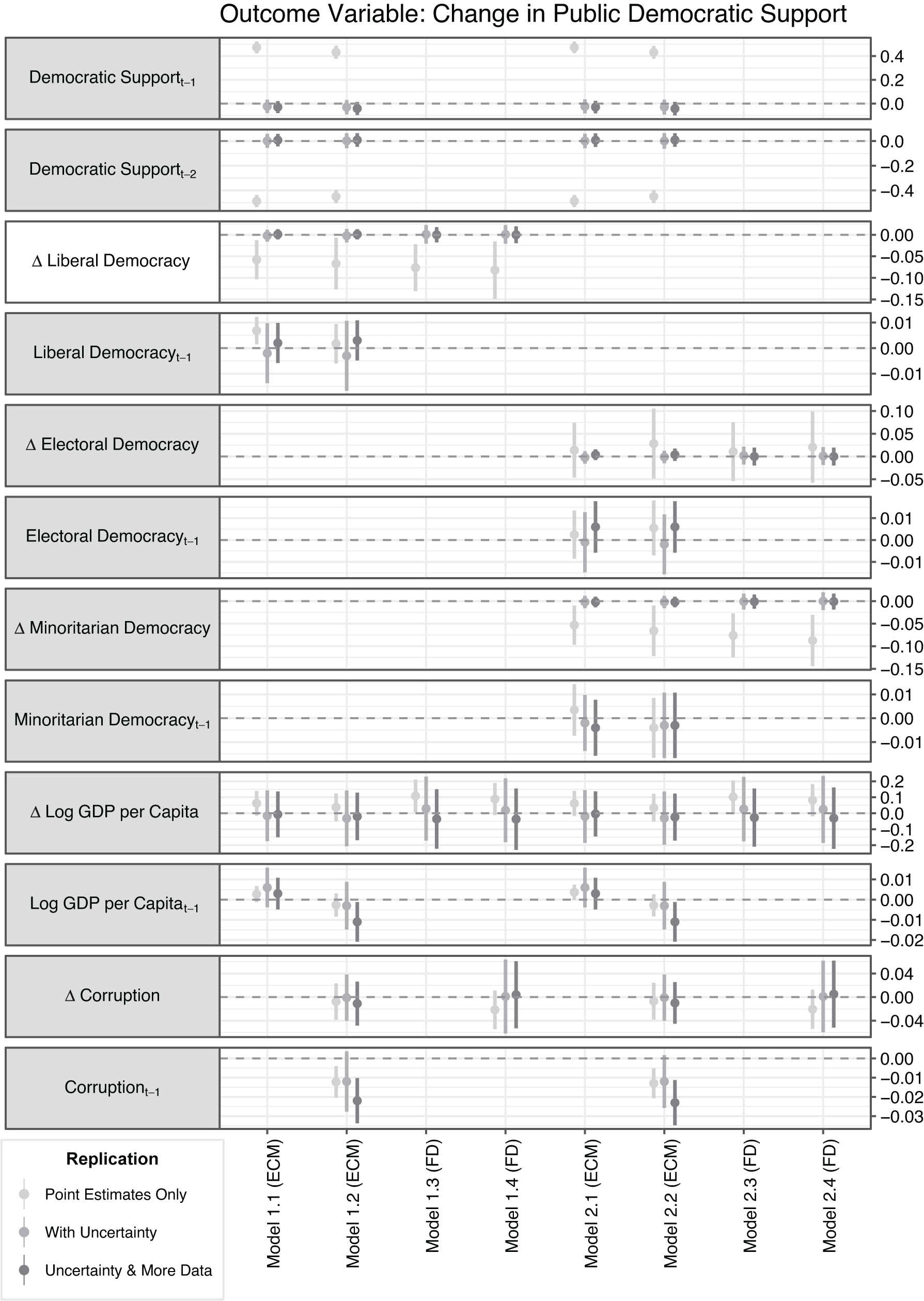

In Figure 2, we examine the thermostatic model of democratic support per Claassen (Reference Claassen2020b, 47, Table 1, 49, Table 2). The negative coefficient estimates for change in liberal democracy in the left-hand set of results, which do not take uncertainty into account, imply that the immediate effect of an increase in the level of democracy is a decline in public support for democracy and of a decrease in democracy an expansion of support—that democratic support does indeed respond thermostatically to democracy. However, the middle results demonstrate that this thermostatic effect, too, does not hold after the measurement uncertainty is accounted for. And again, the right-hand results reveal that the additional data of our extension do not provide support for the original conclusion.

Figure 2. The Effect of Democracy on Change in Public Support with Uncertainty

Note: Replications of Claassen (Reference Claassen2020b), Table 1, 47, and Table 2, 49. Models denoted ECM are error-correction models; those marked FD are first-difference models.

In short, the conclusions of Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b) that democratic support has a positive effect on democracy and change in democracy a negative effect on change in support are not empirically supported once measurement uncertainty is taken into account, even when more data are used.

Discussion

These null results have a number of important substantive implications. First, they underscore that it is crucial to recognize the conditional aspects of the classic theory regarding democracy and democratic support. With respect to how levels of democracy affect public support, even the early proponents of the classic argument did not contend that the mere existence of democratic institutions, no matter how consistently feckless and ineffective, would generate support among the public. Instead, they maintained, public support would be gained through experience with government performance that was generally effective (Easton Reference Easton1965, 119–20; Lipset Reference Lipset1959, 86–9). There is some empirical evidence for this, with government effectiveness positively related to public support among democracies and negatively related in nondemocracies (Magalhães Reference Magalhães2014). The finding of Krieckhaus et al. (Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014) that income inequality is strongly negatively related to public support in democracies suggests that performance regarding redistribution is particularly important. On the reverse part of the classic argument, Qi and Shin (Reference Qi and Shin2011) suggests that democratic support alone cannot be expected to generate democratic change and oppose backsliding. Instead, that work contends that it is the combination of democratic support and dissatisfaction with current regime performance that generates demand for greater democracy. Whether these conditional relationships exist among the newly available latent-variable data on democracy and democratic support remain questions for future research.

Furthermore, these results recommend building recent and more refined conceptualizations of democratic support into our measures. In other words, the survey items employed by Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b)—which ask respondents to assess the desirability or appropriateness of democracy, to compare democracy with some undemocratic alternative, or to assess one of these alternatives—although often used by researchers, may not capture every aspect of democratic support necessary for it to play its hypothesized roles in the classic theory. One possibility is that only those who profess to prefer democracy to its alternatives and also value freedom of expression, freedom of association, and pluralism of opinion will take appropriate action when democracy is threatened (see, e.g., Schedler and Sarsfield Reference Schedler and Sarsfield2007). Another is that respondents’ other values, such as their policy preferences or partisanship, may weigh more heavily than their support for democracy. There is growing evidence that, at least in the United States, there are many for whom these other considerations excuse substantial transgressions against democracy (see Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Simonovits, McCoy, and Littvay Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022). Yet another is that the answers to the above items reflect actual support for democracy only when respondents also either hold a robust understanding of what liberal democracy means or anchor their support in emancipative values of universal freedoms. If they do not, their positive responses to these items indicate support for autocracy instead (see, e.g., Kirsch and Welzel Reference Kirsch and Welzel2019; Wuttke, Gavras, and Schoen Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022). Taking any or all of these into account requires considering the combination of attitudes. Even the inclusion of additional questions in a unidimensional public opinion model such as that provided by Claassen (Reference Claassen2019) will not be sufficient (see, e.g., Wuttke, Gavras, and Schoen Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2020).

Finally, by failing to provide evidence for a short-term relationship between democratic support and democracy, these null findings can be seen to lend additional support to other theories of regime change. There are compelling arguments that episodes of democratic transition (see, e.g., O’Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986) and backsliding (see, e.g., Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman2021) are best understood as products of elite decision making. With respect to the latter, critics have charged that these claims overlook the extent of demand for authoritarian rule among the public (see, e.g., Norris Reference Norris2021). The null results reported here, by finding that year-to-year changes in democratic support bear little relationship to changes in democracy, highlight that levels of public support appear to relate to regime only over the long run (see also Welzel, Inglehart, and Kruse Reference Welzel, Inglehart and Kruse2017), leaving elite decisions as a powerful explanation for when and how short-term developments unfold.

Conclusion

Simply taking measurement uncertainty into account while making no changes to the model specification left the conclusions of both articles examined here without empirical support, even when we added a considerable quantity of data. Methodologically, these results point to the absolute necessity of incorporating measurement uncertainty into analyses that include latent variables. As the use of latent variables grows more common, political scientists should be aware that these variables’ concomitant measurement uncertainty cannot be neglected. Recent cross-national time-series measures of, for example, policy ideology across Europe (developed in Caughey, O’Grady, and Warshaw Reference Caughey, O’Grady and Warshaw2019), immigration attitudes in Europe (presented in Claassen and McLaren Reference Claassen and McLaren2021), and public gender egalitarianism worldwide (introduced in Woo, Allemang, and Solt Reference Woo, Allemang and Solt2022), make possible a host of previously infeasible analyses, but the resulting research cannot be considered robust if it does not also incorporate these measures’ quantified uncertainty.

Our results also have several substantive implications. They highlight theoretical arguments that maintain that levels of democratic support undergird democracy only over the long term and so lend indirect support to other explanations for short-run changes in regime. They also draw attention to the conditional nature of the classic argument on democracy and democratic support as well as to challenges in measuring the concept of democratic support that remain unmet by existing time-series cross-sectional latent-variable models. Most importantly, the sanguine assessment that readers may draw from Claassen (Reference Claassen2020a; Reference Claassen2020b)—that the fates of democracies depend on public support and, when eroded, their publics will rally to them—is not supported by the current evidence. Those who would defend democracy have no grounds for being complacent.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000429.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication files are available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/XAUF3H.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The three authors contributed equally to this work. We thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. All errors remain our own.

FUNDING STATEMENT

Yue Hu acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72004109).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.