In almost the entire second half of the last century, Lucio Parenzan was one of the most charismatic leaders working in the field of congenital heart disease in Europe. After his death, it is appropriate to reflect on his personality and his many achievements. Everybody who came in contact with him was struck by his personality and his deeply rooted unconventional approach to almost everything.

What made this man so special? Why would a man like him make such a fundamentally important career when he never had the most impressive publication record, had not given his name to a cardiac operation, or was particularly famous for his surgical skills? He also worked in the local hospital in Bergamo, in Italy, which did not even have university affiliation. Lucio, nonetheless, became the pioneer of paediatric cardiac surgery in Italy.

There are many very good reasons why Lucio made the career he made. Lucio was a man of vivid intelligence, extremely fast in thought and action, who had the ability to distinguish the important from the unimportant, according to his personal scale, within seconds. He did not like problems, and therefore solved them when they occurred simply to get rid of them. Nothing seemed impossible, and therefore many solutions had to be found to keep up with his rhythm and demand. For example, if you wanted to learn something in France but you do not speak French, he used to say without hesitation, “Go and learn the language”.

When asking for advice, the classic way of exposing a problem, followed by a proposal for its solution, did not work with him. One had better chances by telling him about a solution. He would then interrupt and ask “but what is the problem?” This would then present the brief window of opportunity to expose to him the actual problem, and then obtain his approval to make the necessary changes to implement the previously suggested solution – an unusual, but certainly very efficacious, tactic.

He loved to provoke and to challenge. When one of his assistants fell ill with hepatitis, he promptly went to pay him a visit in the ward to which he had been admitted. He brought a pile of scientific articles relating to paediatric cardiac surgery and said, “Finally you have some time to read”.

The man was full of love. He loved his wife and his children. He loved the people with whom he worked and his patients, and he enjoyed the admiration and love he received in return. Many of his staffs would walk many extra miles for him and his ideas.

Every professional category in his department fell under the spell of his charisma. Lucio was able to recognise the importance of every single job to achieve the goal of providing good care to children with heart disease. He wanted the corridors to be swept first on one side. When this side was dry, the other side could be swept. This approach allowed circulation through the department and avoided dirty footsteps in the wet area. The equal consideration he gave to every professional category built him strong allies and created a team with a superb working morale. Lucio Parenzan had endless trust on the people with whom he worked. He stimulated and pushed people to make the very best of themselves. His pupils tell stories, such as being trusted to repair a patient with tetralogy of Fallot when aged no more than 27. Among his pupils were cardiologists just as much as surgeons. Secretaries worked 7 days a week if necessary, and were just as involved as any other person in the department.

Lucio looked up to the cardiac surgeons who invented new operations and admired the surgical virtuosos. During the early days of cardiac surgery, he was extremely pro-American and tried to bring any innovation in cardiac surgery over the ocean and implement it in his department. He trusted his young assistants to learn and perform new techniques, and sent them around the world to satisfy his thirst for knowledge and to introduce innovation in his department. Many of the innovators and fabulous surgeons from outside Italy became dear friends of Lucio and his family in the broadest sense. This obviously included his real family, but many others had the honor and enjoyed being part of this broad family in their professional and personal lives.

The most innovative years of cardiac surgery were probably between the late 50s and the mid 80s. Lucio was a full member of these exciting years. When ground-breaking innovations became more scarce in the field, Lucio shifted his interest into a new direction. He had succeeded in developing paediatric cardiac surgery in Italy. His next challenge was to introduce the discipline in environments where this had not happened. He fell in love with Africa and provided care for many children by developing a cardiac service in Kenya. More importantly, he realised that education, more than money, was the key to making cardiac care possible around the world. The idea of the International Heart School and the implementation of the project was a magnificent brainchild of Lucio. Lucio never used the stories about the poor African children with heart disease to raise money. He had found a solution to the problem, the means of providing medical education in underprivileged countries, and wanted to implement it. Once again he achieved a great deal, but in all honesty he deserved stronger and much more support. He was ahead of his times.

Few recognise that advancement is still possible today, and requires courage and personality. Knowing Lucio, even at his advanced age, it was very apparent that he had huge originality and the personality of an icebreaker. He had fought and won many battles, which put him far ahead of his time. It is all too easy, back then, to state that all was possible when people had the freedom to do what they wanted. Lucio did and had to fight for innovation. We can only hope that the regulations and working environments of today would not have made it impossible for him to achieve his goals. Knowing him, we believe they would not have deterred him.

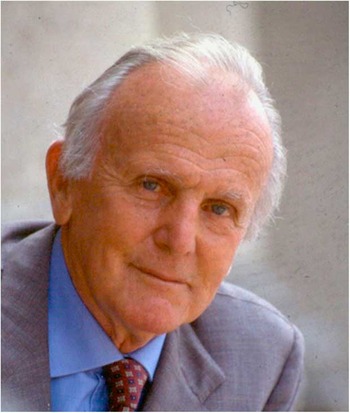

Lucio's life ended in Bergamo at the Hospital where he had spent so many years, surrounded by his wife Laura and his children Antonio, Guido, Giovanni, and Chiara, together with numerous pupils he used to name “my boys”, who grew up under his guidance. They will never forget the huge moral and professional support they received from him (Figs 1–3).

Figure 1 Lucio is pictured in the years of his maturity.

Figure 2 Lucio is pictured with the Ospedali Riuniti soccer team, which contained many of his “boys”. Lucio is second from the left in the back row, with Piero Abbruzzese to his left. Giancarlo Crupi is holding the ball in the front row, with Paolo Ferazzi at the right end of the front row.

Figure 3 The young Lucio is shown in the intensive care unit.