Introduction

Mental health stigma: a global problem

The term ‘stigma’ encompasses people's knowledge, negative attitudes and behaviours toward (or by) a certain group or individual deemed ‘unacceptably different’ (Scambler, Reference Scambler1998; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009). This paradigm links knowledge, attitude and behaviour, and has also been defined as problems in three domains: ignorance, prejudice and discrimination (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Kassam and Lewis-Holmes2008).

Mental health stigma has been shown to be widespread globally, regardless of region (Pescosolido et al., Reference Pescosolido, Medina, Martin and Long2013). For example, a 2009 study found rates of experienced discrimination by people with schizophrenia were high and consistent across 27 countries (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009).

The far-reaching negative impact of mental health-related stigma and discrimination has been extensively documented and has even been described by those with mental illness as ‘worse than the illness itself’ (Henderson and Thornicroft, Reference Henderson and Thornicroft2009). There is evidence of negative impacts of stigma across multiple domains of life – for example, stigma is associated with reduced employment opportunities and corresponding poverty, relationship difficulties, reduced help-seeking behaviour and poorer quality health care (Corrigan, Reference Corrigan2004; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Howard and Thornicroft2008; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese2009; Knaak et al., Reference Knaak, Mantler and Szeto2017). Additionally, people with mental illness often experience severe human rights abuses and lack of freedoms, which act as barriers to social inclusion (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper J, Eaton, Herrman, Herzallah M, Huang, Jordans, Kleinman, Medina-Mora, Morgan, Niaz, Omigbodun, Prince, Rahman, Saraceno, Sarkar, De Silva, Singh, Stein, Sunkel and Unützer2018).

Mental health stigma and discrimination have been identified as major factors for low levels of investment and political will for reform in many countries, which in turn reduces access to care and contributes to excess morbidity and mortality for people with mental illness (Saraceno et al., Reference Saraceno, Van Ommeren, Batniji, Cohen, Gureje, Mahoney, Sridhar and Underhill2007). Given its wide-ranging detrimental impact, it is important to address stigma urgently and effectively (Henderson and Thornicroft, Reference Henderson and Thornicroft2009).

Stigma reduction interventions: state of the research

A substantial number of small-scale and short-term interventions have emerged in the past few decades focusing on reducing mental health stigma and several recent systematic reviews examine their effectiveness (Corrigan and Scott, Reference Corrigan and Scott2012; Clement et al., Reference Clement, Lassman, Barley, Evans-Lacko, Williams, Yamaguchi, Slade, Rusch and Thornicroft2013; Heim et al., Reference Heim, Kohrt, Koschorke, Milenova and Thronicroft2018; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Clement, Marcus, Stona, Bezborodovs, Evans-Lacko, Palacios, Docherty, Barley, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, Henderson and Thornicroft2018; Mellor, Reference Mellor2018; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan A, Reavley, Ross, Too and Jorm2018).

Three overarching methods of reducing stigma have been conceptualised and tested in recent years: education (addressing myths and misconceptions), contact (direct or indirect interactions with people with the stigmatised condition) and protest (public demonstrations and campaigns against injustice) (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, River, Lundin, Penn, Uphoff-Wasowski, Campion, Mathisen, Gagnon, Bergman, Goldstein and Kubiak2001). The evidence indicates that there are a number of education and contact-based interventions which produce small to moderate effect sizes on stigma reduction, yet there is minimal evidence long-term and study quality is not always sufficient (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'Reilly and Henderson2016; Gronholm et al., Reference Gronholm, Henderson, Deb and Thornicroft2017; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan A, Reavley, Ross, Too and Jorm2018). The protest method has not shown evidence of effectiveness (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, River, Lundin, Penn, Uphoff-Wasowski, Campion, Mathisen, Gagnon, Bergman, Goldstein and Kubiak2001).

A few studies have been conducted to identify key ingredients for very specific contexts or stigma types (Pinfold et al., Reference Pinfold, Thornicroft, Huxley and Farmer2005; Mittal et al., Reference Mittal, Sullivan, Chekuri, Allee and Corrigan2012; Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Vega, Larson, Michaels, Mcclintock, Krzyzanowski, Gause and Buchholz2013, Reference Corrigan, Michaels, Vega, Gause, Larson, Krzyzanowski and Botcheva2014; Knaak et al., Reference Knaak, Modgill and Patten2014). While these studies have provided useful setting-specific evidence, there have been no systematic reviews which identify core components of mental health stigma reduction interventions in LMICs or review their cultural variations. Similarly, there has been little research on how these components relate to other intervention factors – such as target population or type of stigma. A more detailed analysis would be helpful to understand what makes stigma reduction interventions effective in various contexts.

Investment by donor organisations for mental health has been noticeably increasing in high-income countries (HICs) over the past few years; for example, in January 2019 the Wellcome Trust announced £200 million in funding (Wellcome Trust, 2019). It is crucial that mental health researchers capitalise on this influx of support. In order to do so, they need to have sufficient evidence for how to design stigma reduction interventions both effectively and appropriately.

The scarcity of research into stigma reduction interventions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) is consistent with the wider mental health research gap in resource-poor settings (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Patel, Joestl, March, Insel, Daar, Bordin, Costello, Durkin, Fairburn, Glass, Hall, Huang, Hyman, Jamison, Kaaya, Kapur, Kleinman, Ogunniyi, Otero-Ojeda, Poo, Ravindranath, Sahakian, Saxena, Singer, Stein, Anderson, Dhansay, Ewart, Phillips, Shurin and Walport2011; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Borges, Bruffaerts, Bunting, De Almeida J, Florescu, De Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, Hinkov, Karam, Kawakami, Lee, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, De Galvis and Kessler R2017; Alonso et al., Reference Alonso, Liu, Evans-Lacko, Sadikova, Sampson, Chatterji, Abdulmalik, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Andrade, Bruffaerts, Cardoso, Cia, Florescu, De Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, De Jonge, Karam, Kawakami, Kovess-Masfety, Lee, Levinson, Medina-Mora, Navarro-Mateu, Pennell, Piazza, Posada-Villa, Ten Have, Zarkov, Kessler and Thornicroft2018). For example, only four out of 62 studies included in a recent mental health stigma-related review were from LMICs (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan A, Reavley, Ross, Too and Jorm2018). Intervention transferability from HICs to LMICs is context-dependent and cannot be assumed; therefore, there still is a vast gap in knowledge surrounding what works in diverse cultural contexts and why (Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Clement, Marcus, Stona, Bezborodovs, Evans-Lacko, Palacios, Docherty, Barley, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, Henderson and Thornicroft2018). Given this systematic review's wide scope, cultural differences will be examined between geographic regions as classified by the World Bank.

This systematic review aims to address the scarcity of stigma research in LMICs by identifying and categorising core components of effective mental health stigma reduction interventions in LMICs and comparing these components across cultures.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (ID 136008).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

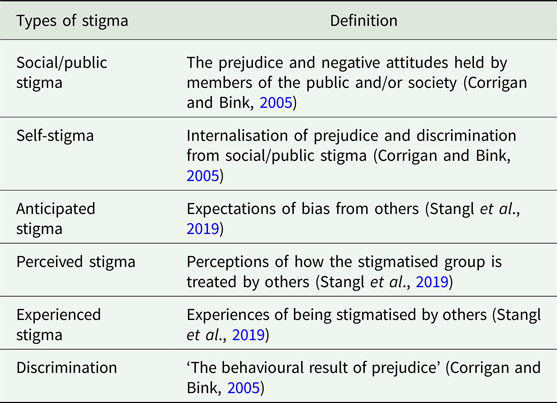

This review included studies which contain interventions aiming to reduce any type of stigma related to mental health; this includes social/public stigma, self-stigma, anticipated, perceived, experienced stigma, or discrimination (see Table 1). Studies focusing on any other stigmatised condition were excluded, including HIV, neurological conditions, substance misuse and epilepsy. Interventions of all sizes, durations and effect sizes were included. There were no restrictions in terms of study participants. Inactive controls, treatment as usual controls and baseline assessments of intervention groups were all included, as long as outcome measures were taken before and after the intervention.

Table 1. Definitions of types of stigma and discrimination

All experimental designs were included, as long as they measured the effectiveness of stigma reduction interventions. To be included, interventions had to have been conducted in countries classified as LMIC by the World Bank (The World Bank, 2019). There were no publishing date restrictions. Following established frameworks on conceptualising stigma, studies had to include at least one measure of mental health-related stigma linked to knowledge, attitudes or behaviour (Corrigan and Scott, Reference Corrigan and Scott2012; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'Reilly and Henderson2016).

Search strategy

The database search strategy was developed using earlier stigma-related systematic reviews as a guide (Heim et al., Reference Heim, Kohrt, Koschorke, Milenova and Thronicroft2018; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Clement, Marcus, Stona, Bezborodovs, Evans-Lacko, Palacios, Docherty, Barley, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, Henderson and Thornicroft2018; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan A, Reavley, Ross, Too and Jorm2018; Kemp et al., Reference Kemp, Jarrett, Kwon, Song, Jetté, Sapag J, Bass, Murray, Rao and Baral2019) and used both subject headings and keywords. Four categories of terms ('stigma’, ‘mental health’, ‘intervention’, ‘low- and middle-income countries’) were expanded with synonyms and related subject headings, connected within categories with ‘OR’ and between categories with ‘AND’. The full search strategy for MEDLINE, exemplifying this process, is provided within online Supplementary Material. Searches were restricted to English and Spanish, and to humans.

The following seven databases were searched on 13 May 2019: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Global Health, PsycINFO, EMBASE and Scopus.

Additional search methods comprised of citation checking, hand checking reference lists from other related systematic reviews on stigma, and experts in the field (NV, JE) were consulted to identify any missing papers or grey literature.

Study selection

All titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria by the lead author (JC), and 10% of titles and abstracts were screened by a second reviewer to establish consistency. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. The study supervisor with knowledge of the review topic (NV) decided any on unresolved discrepancies.

Full-text versions of papers were retrieved for all potentially relevant studies and screened against the inclusion criteria. If the full text of a study was not available, the author was contacted. If there was no reply, the study was excluded. A third reviewer screened 10% of full-text papers.

Quality assessment

Assessment of quality and risk of bias across studies was conducted with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Fabregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O'Cathain, Rousseau, Vedel and Pluye2018). This tool was chosen because multiple study designs were included in this review, and the MMAT has five unique criteria for each design in addition to two core criteria.

All studies marked for inclusion were assessed for quality and the third reviewer separately assessed 10% for consistency. For a study to be included, the two standardised core criteria had to be met. As recommended by the MMAT, studies of poor or very poor quality – two or less of five criteria met – were included in the main analysis but later separated out.

Data extraction

The framework for data extraction was developed a priori. Data was extracted on general study information (e.g. author, year), study characteristics (e.g. design, aims), study methods (e.g. methods of recruitment), intervention characteristics (e.g. intervention methods, dissemination medium), results (e.g. outcomes) and methodological quality. A full list of fields is provided in online Supplementary Material. Missing data was requested from authors where possible.

Data analysis

Only interventions which produced at least a partially positive effect for stigma-related outcomes were included in the main analysis. Ineffective interventions were described separately, to demonstrate how their components differed.

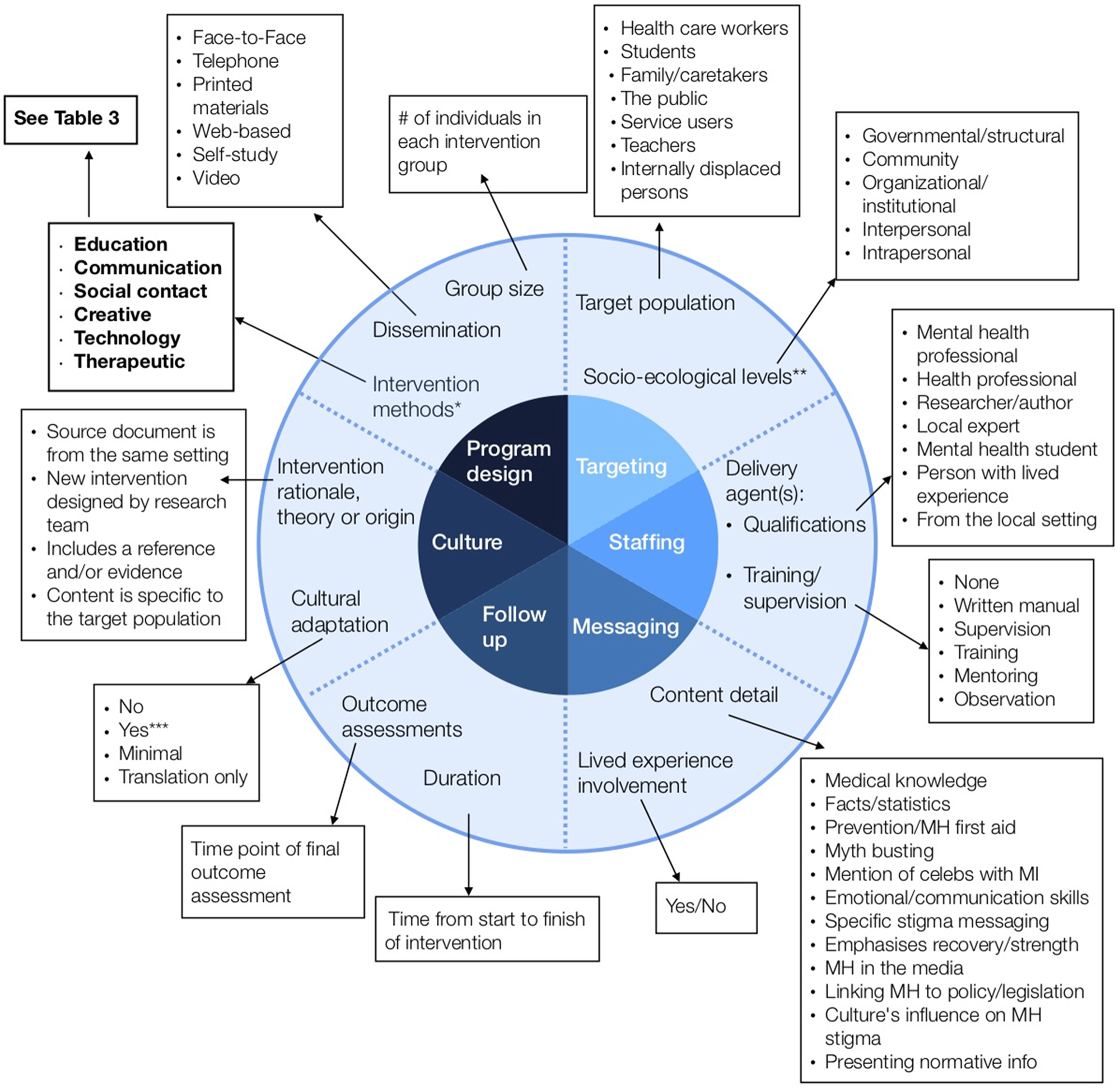

With previously conducted research and frameworks as a guide, a ‘best fit’ framework synthesis was chosen as the main method of analysis for this review (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Booth, Leaviss and Rick2013). As the most broadly encompassing framework, Corrigan's five categories of stigma reduction ingredients were the starting point for the synthesis: programme design, targeting, staffing, messaging and follow-up/evaluation. (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Vega, Larson, Michaels, Mcclintock, Krzyzanowski, Gause and Buchholz2013).

In order to address the cultural focus of this review, the sixth category of components was added: Culture. Data extraction fields related to this included: detail on the intervention rationale, theory or origin (where the content came from), as well as whether the publications mention any kind of cultural adaptation or taking account of local beliefs. This data helped determine the influence of culture on the intervention and provide detail on transferability. World Bank regions were also analysed individually, in order to describe differences in components by region.

Data was extracted from each study based on the authors' literal descriptions in the publications, without a priori labels. A codebook was then created for each data extraction worksheet field, grouping information within the categories using inductive thematic analysis grounded in the extracted data. The framework synthesis then allowed for the expansion of Corrigan's categories (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Booth and Cooper2011) and the creation of a new framework (see Fig. 2). A narrative synthesis was used to explain the coded data. The final overview of components therefore only included those which the publication reported on.

Results

Search results

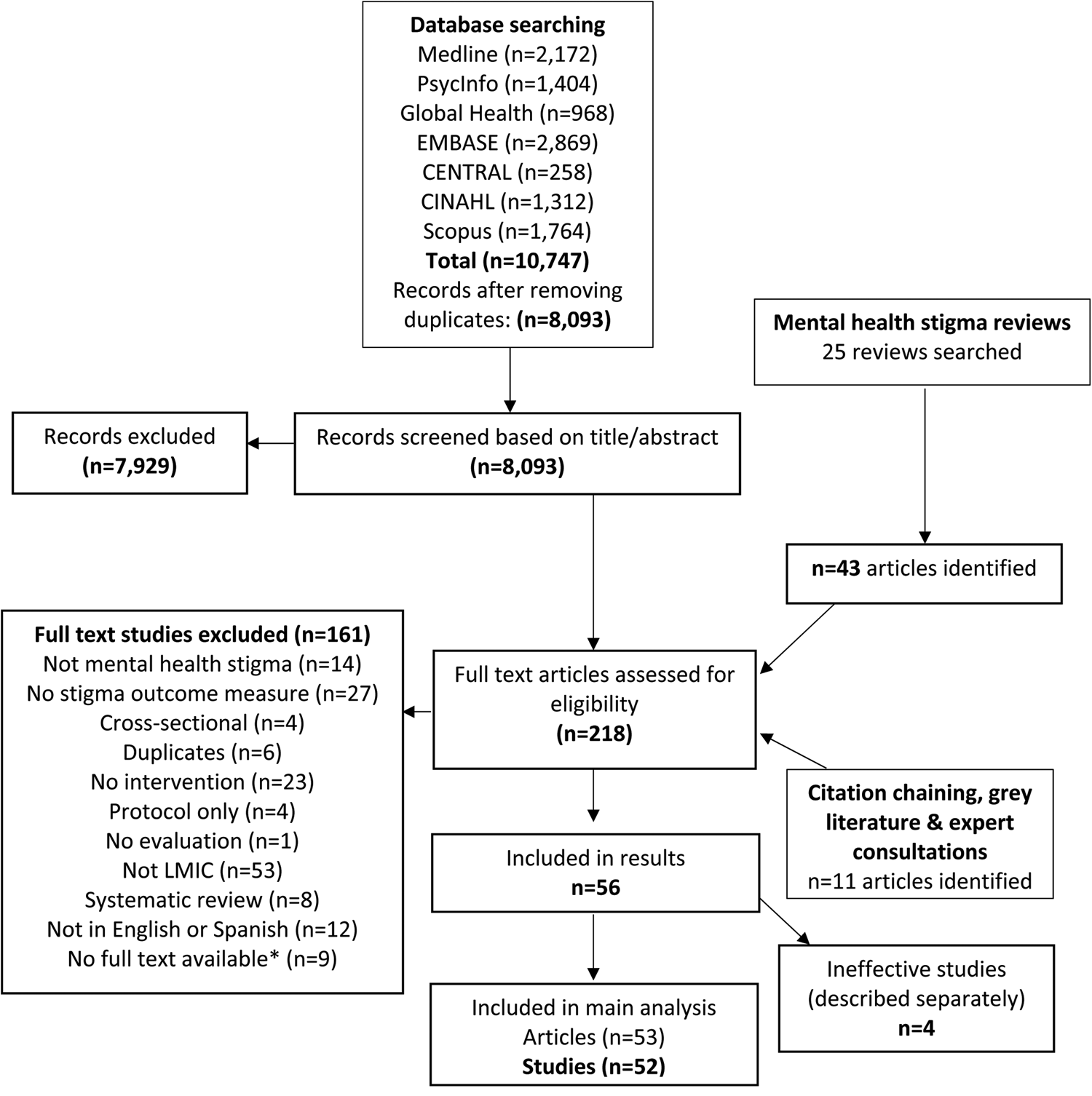

The final search produced 56 studies (57 articles) which were deemed eligible for inclusion (see Fig. 1). Four studies were ineffective and analysed separately, to demonstrate how their components differed.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart of selection of articles and sources included in the review. *Authors contacted with no response

Study characteristics

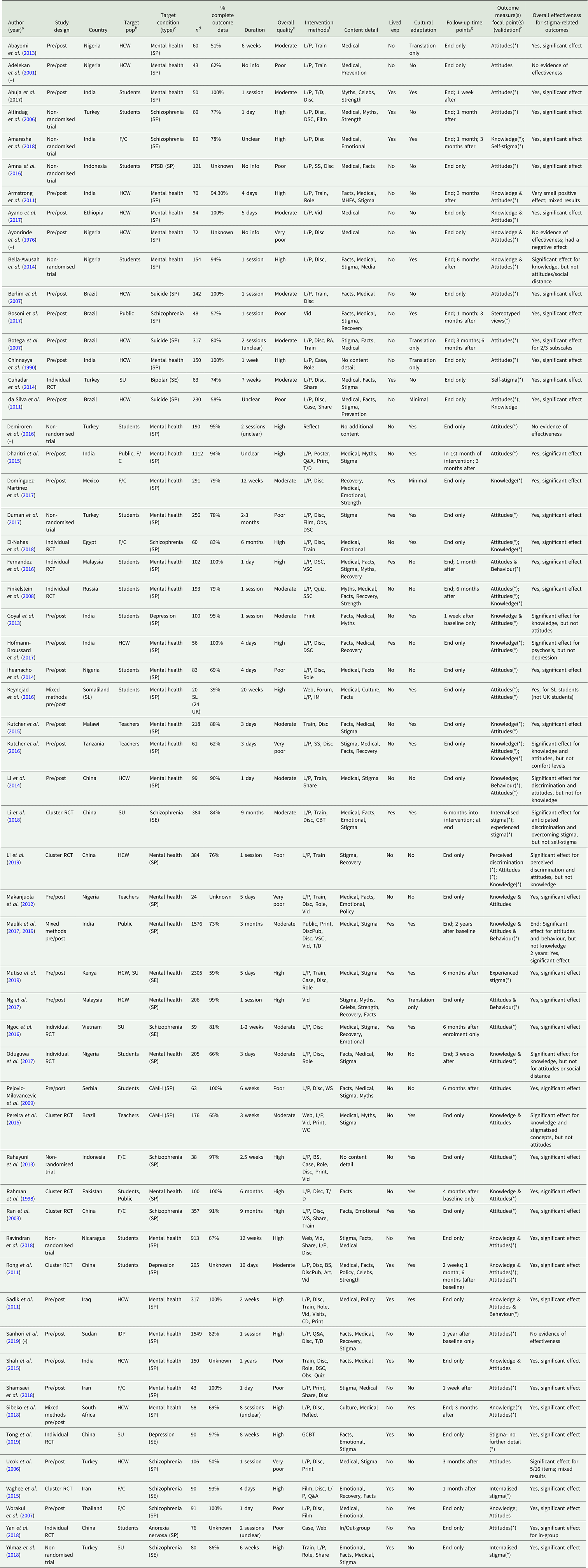

See Table 2 for key characteristics of each study.

Table 2. Key characteristics and components of included studies

Note: Studies with a ‘(–)’ in the first column after the author's name were ineffective for stigma-related outcomes and excluded from the main analysis.

a Year, year of publication.

b Target population: HCW, health care worker; F/C, family/caregiver; Public, the general public; SU, service user; IDP, internally displaced persons.

c Target condition (type): SP, stigma practices (expressed by those perpetuating stigma); SE, Stigma experiences (those felt by the stigmatised individual); CAMH, child and adolescent mental health; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

d N, number of participants at baseline.

e Study quality was based on the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

f Intervention methods: see Table 3 for component codes.

g Follow-up time points: after baseline. End = immediately after intervention; after = after the end of the intervention.

h Outcome measure focal points = what are study outcome measures looking at as a proxy for stigma. Validation: (*) = measure is validated in some way; no ‘(*)’ = measure was developed ad hoc by authors with no validation OR no info given. One measure which addresses more than one focal point connects with ‘&’; two separate measures are indicated with ‘;’. Full names/descriptions of measures available upon request.

The quality of studies varied, with 38 studies (73%) fulfilling at least three of five MMAT quality criteria (considered moderate and high-quality studies). Eleven studies (21%) were of poor quality with one to three of criteria fulfilled, and three (6%) were of very poor quality (i.e. no criteria fulfilled).

The majority of studies were conducted in East Asia and Pacific (n = 13, 25%) or Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 11, 21%), but all World Bank regions were represented apart from North America, due to the review's LMIC restriction. Studies took place in 24 countries overall. Only two studies were published prior to 2000, and about half (n = 26) have been published since 2016; 12 were published in 2018 or 2019. Almost a third of studies (n = 15, 29%) were individual or cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and 11 of these (73%) were published since 2014. The majority of studies (n = 27, 52%) were pre/post studies.

Most studies (n = 29, 56%) targeted general mental health stigma. Twelve studies looked at schizophrenia, three studies focused on suicide, three on depression, two on child and adolescent mental health, and one each on bipolar disorder, anorexia nervosa and post-traumatic stress disorder.

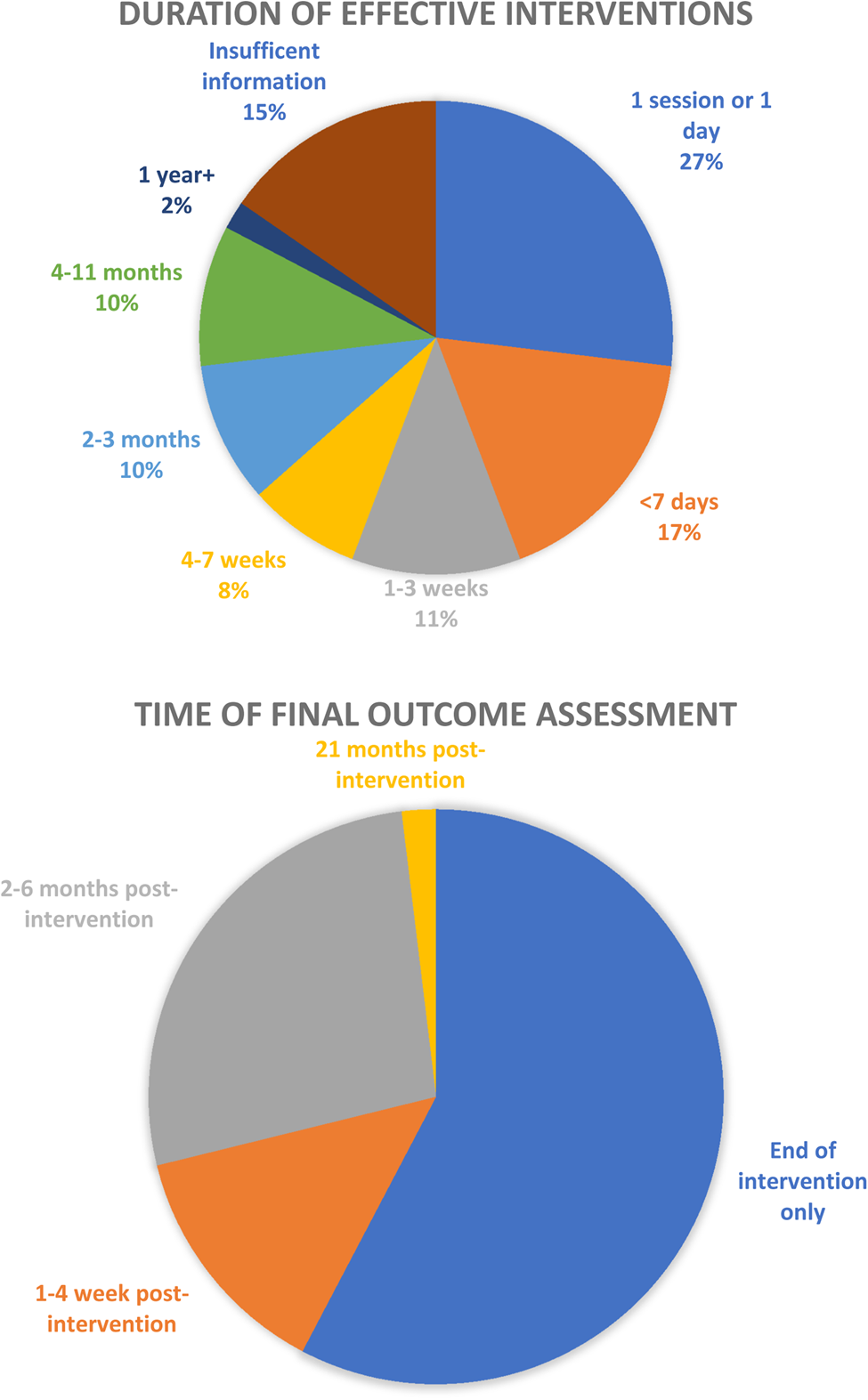

The majority of studies (n = 30, 58%) had their final outcome assessment directly at the end of the intervention, but 14 of these had an intervention duration of 4 weeks or longer. Fifteen (29%) followed up after 2 months or longer. Thirty-nine articles (74%) found a significant positive result for all main stigma outcomes and 13 (25%) found at least a small positive result for some but not all stigma outcomes. Of these 13, ten lasted less than a week.

Among the moderate or high-quality studies (n = 38), 14 (37%) followed up at least 1 month after the intervention finished and ten of these (71%) still found a significant positive effect on stigma outcomes at the later final assessment, indicating that it is possible to maintain stigma reduction over the medium term.

Intervention components and categorisation

From the best-fit framework synthesis, the categorisation of components was developed into a new framework (see Fig. 2) which was used to organise and analyse extracted data. This produced six categories of components: programme design, targeting, staffing, messaging, follow-up and culture, described in further detail below. Full data is available upon request.

Fig. 2. Framework of core components of anti-stigma interventions in low- and middle- income countries. The inner circle represents six overarching ‘categories’; the outer circle represents ‘components’ within each category; the boxes represent ‘sub-components’ within each component. Intervention methods are further broken down into ‘elements’ in Table 3. This framework of core components of anti-stigma interventions was developed by the authors as a composite of other analysis frames (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, Reference Heijnders and Van Der Meij2006; Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Vega, Larson, Michaels, Mcclintock, Krzyzanowski, Gause and Buchholz2013). *Intervention methods: the six sub-components are further coded into 32 elements; see Table 3. **Socio-ecological levels: based on Heijnders' framework (Heijnders & Van Der Meij, Reference Heijnders and Van Der Meij2006). ***Cultural adaptation: ‘yes’ = local beliefs/culture are taken into account; the intervention at least partially originated from the local context; or, the intervention was piloted/field-tested

Programme design

The programme design category captured group size, dissemination and intervention method components. As the quantity and variety of intervention method sub-components identified through thematic analysis was vast, these were further organised into ‘elements’ (see Table 3). Most studies (n = 49, 94%) utilised at least one educational component and only eight did not include the most common element, ‘lectures/presentations’. Almost all (n = 48, 92%) reported using more than one element and 20 studies (38%) used four or more intervention method elements.

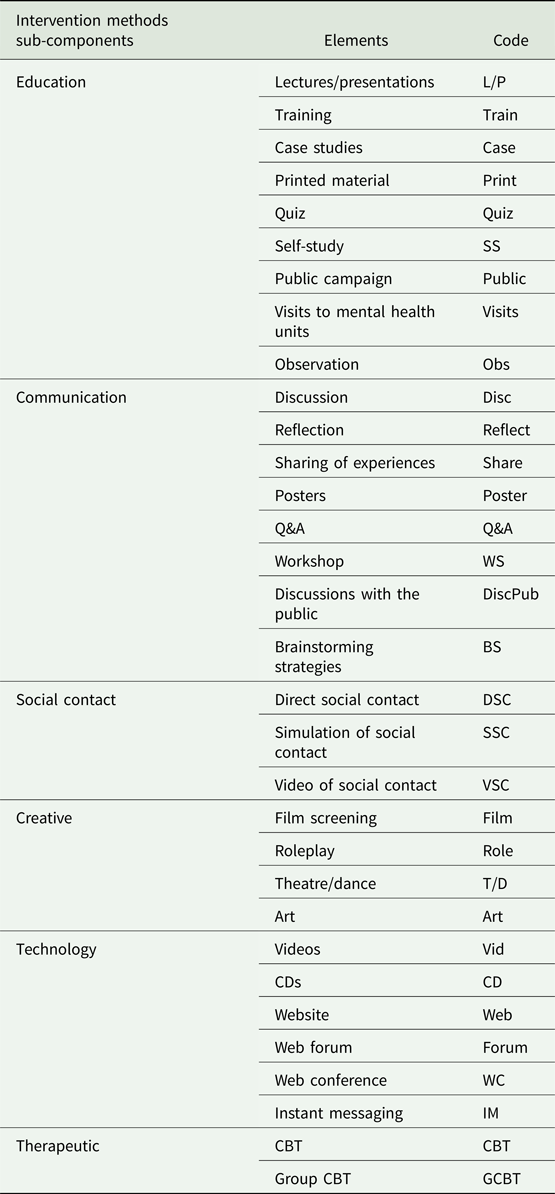

Table 3. ‘Intervention methods’ sub-components and elements used in anti-stigma interventions in low-and middle-income countries

Across all studies, as shown in Table 3, educational sub-components were documented most frequently as a method (n = 83), followed by communication (n = 58), technology (n = 21), creative (n = 19), social contact (n = 8) and therapeutic (n = 3). As for group size, the majority were between 11 and 29 (n = 15, 29%) and between 30 and 99 (n = 8, 15%) or it was unclear/unreported (n = 21, 40%). Of the 39 interventions effective for all stigma outcomes, only one described using educational methods only, and just 14 (36%) used solely education and communication methods.

Targeting

The most frequent target populations were health care workers and students (both n = 16, 31%), although some studies focused on more than one group.

Staffing

The most common delivery agents were mental health professionals (MHP) (n = 23, 44%). Of these, only six explicitly mentioned that the MHP came from inside the setting where the research took place. Two (4%) defined at least one of their delivery agents as someone with lived experience. Of the total, 54% of studies (n = 28) did not mention any delivery agent training or supervision.

Messaging

The content of messaging did vary, but most interventions (n = 42, 81%) described their intervention as being based on medical knowledge, and only half of the studies (n = 26) explicitly mentioned stigma or discrimination in their description. While this does not necessarily indicate that a discussion of stigma was excluded from the other 26 interventions, it was not reported. A variety of other themes were addressed in smaller numbers including teaching emotional/communication skills (n = 11); myth-busting (n = 9); emphasising recovery and strength of people with mental illness (n = 13); and discussing the media's impact on stigma (n = 4).

Twenty-one studies (40%) involved someone with lived experience in the intervention development or delivery. This is in contrast to educational methods, which were used in almost all interventions (94%). No interventions reported using the protest as a method.

Of the 21 studies which involved someone with lived experience in intervention development or delivery, 86% were effective for all stigma-related outcomes compared to only 74% of studies which did not involve someone with lived experience. Of these 21, 15 incorporated emotional skills or emphasised recovery/strength of people with mental illness. In comparison, only five of the 31 studies which did not involve someone with lived experience incorporated emotional skills or emphasised recovery/strength.

Follow-up

Approximately a quarter of interventions (n = 14) lasted for one session or 1 day only. Nine (16%) lasted for less than a week, six (10%) lasted between 1 and 3 weeks, and fifteen (29%) lasted 4 weeks or longer. The majority of studies (n = 30, 58%) had their final outcome assessment directly at the end of the intervention. However, of these 30, 14 interventions lasted 4 weeks or longer (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Duration of effective interventions and length of follow-up.

Culture

Only 11 studies (21%) originated from ‘inside’ the setting (the source document for the intervention originated from the same setting it was used in) and were referenced (meaning the publication provided a cited resource for the intervention). Twelve studies (23%) were either ‘outside’ or new, had no reference and were not targeted/provided no targeting information. Thirty-five studies (67%) included a reference or evidence for their intervention. Thirty-two studies (62%) used interventions which originated ‘outside’ the country (such as source documents from the World Health Organisation) or did not provide information. Twenty-five studies (48%) were culturally adapted.

Only four of 52 studies (8%) took place in low-income countries; 21 (40%) took place in lower-middle-income countries and the remaining 27 (52%) took place in upper-middle-income countries. Given the geographic variety of results and as most regions were dominated by one country, analysis of components between World Bank regions was deemed an appropriate perspective on whether components vary between cultures.

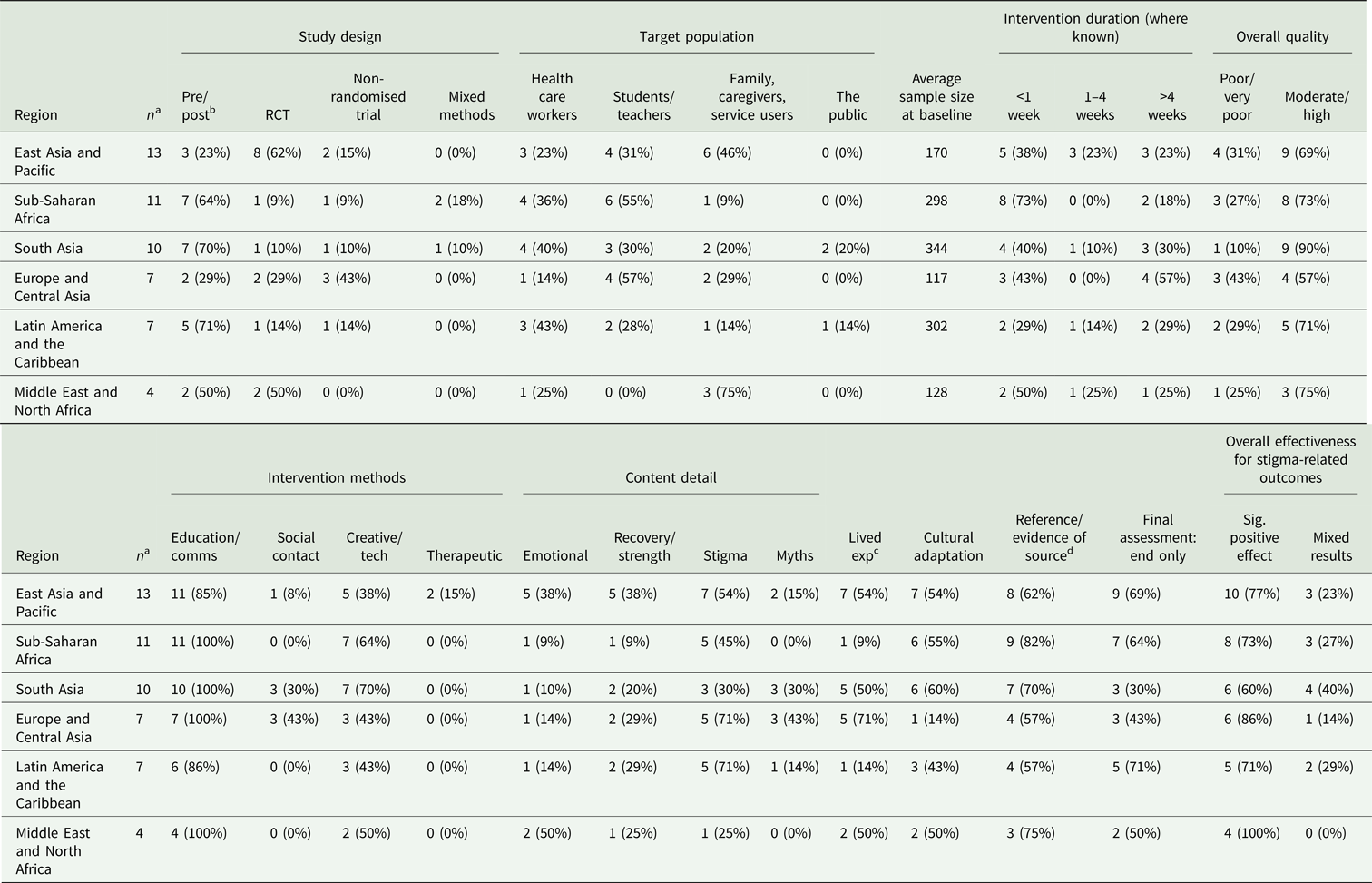

Key intervention components did vary across regions (see Table 4). East Asia and Pacific had the highest number and percentage of: RCTs (n = 8, 62% of 13 studies) and interventions using emotional skills or emphasising recovery (n = 10, 76%). The region only utilised social contact in one study, however.

Table 4. Study components by geographical region

a Number of studies per region.

b Percentages are out of total studies in each region.

c Lived exp = involving someone with lived experience in intervention development/delivery.

d Reference/evidence of source = the origin of the intervention is referenced/evidence.

Sub-Saharan Africa had the lowest number and percentage of RCTs (n = 1, 9% of 11 studies), of interventions lasting longer than a week (n = 2, 18%), of interventions using emotional skills or emphasising recovery (n = 2, 18%), or involving someone with lived experience (n = 1, 9%). This region did have a good number of moderate and high-quality studies (n = 8, 73%), but no interventions featured social contact. This region also had the highest number of interventions whose source was referenced or evidenced (n = 9, 82%).

South Asia had the highest percentage of moderate or high-quality studies, at 90%. Europe and Central Asia had the most interventions lasting more than 1 month (n = 4, 57%). All regions were dominated by studies from one country: China (n = 7), India (n = 9), Nigeria (n = 5), Turkey (n = 5), Iran (n = 2) and Brazil (n = 5); combined they made up 63% (n = 33) of all effective studies.

Ineffective studies

Only four (7%) of the 56 studies reported in Table 2 did not find any evidence of effectiveness and two were of poor or very poor methodological quality. These ineffective interventions did not use any social contact, technological or therapeutic methods. Two of the four provided no information on either delivery agents or their training/supervision and only one included explicit messaging on stigma or recovery. None involved someone with lived experience and only one was culturally adapted.

Discussion

Overall, the vast majority of included studies were effective in reducing mental health stigma to some degree, at least in the short term, which is consistent with previous findings (Gronholm et al., Reference Gronholm, Henderson, Deb and Thornicroft2017; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan A, Reavley, Ross, Too and Jorm2018).

There is some congruity in components between cultures, but generally, they vary widely and may reflect various cultural differences within the local setting. The generalisability of regional results to the wider World Bank regions is limited, as results were dominated by studies from one country in each region (China, India, Nigeria, Turkey, Iran and Brazil). Few studies originated from the local setting and were referenced and less than half met the criteria to be considered culturally adapted. This assumption of transferability between settings by some studies disregards the importance of cultural relevance (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Binagwaho, Martell and Mulley2014; Rathod and Kingdon, Reference Rathod and Kingdon2014) and evidence that local concepts of stigma are complex (Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Jadhav, Raguram, Vounatsou and Littlewood2001).

Despite evidence of the effectiveness of social contact (Corrigan and Scott, Reference Corrigan and Scott2012), no region overtly described using social contact in more than half of studies and almost no studies defined any of their delivery agents as someone with lived experience. Nonetheless, it is possible that social contact was more frequently used and included in other intervention components, such as through lectures and presentations. However, if not explicitly mentioned, it was unable to be reported here.

The results of this review also indicate that more complex interventions (i.e. interventions including more unique individual methodological sub-components and elements) are not necessarily more effective. Almost all studies used self-report measures and had limited length of follow-up, which reflects the complexity of measuring real-life discrimination experience, hence use of, for example, intended behaviour as proxies.

The results of this systematic review reiterate some main findings from other recent stigma-related reviews (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'Reilly and Henderson2016; Heim et al., Reference Heim, Kohrt, Koschorke, Milenova and Thronicroft2018; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Clement, Marcus, Stona, Bezborodovs, Evans-Lacko, Palacios, Docherty, Barley, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, Henderson and Thornicroft2018; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan A, Reavley, Ross, Too and Jorm2018; Heim et al., Reference Heim, Henderson, Kohrt, Koschorke, Milenova and Thornicroft2019). However, these reviews also found minimal research in LMICs, limited cultural adaptation, short intervention duration, poor study quality and mostly only short-term follow-up. Yet in comparison, this review found a higher number of effective studies with more than a 4-week follow-up, the majority of which were of moderate or high quality and more studies which originated from inside the local setting. The majority of papers included here have been published since 2014. This indicates that the overall quantity and quality of stigma reduction studies has increased over the past several years.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review providing an in-depth analysis of core components of mental health stigma reduction interventions in LMICs.

The relatively large number of included studies provides a thorough analysis of intervention components and the use of an explicit evidence-based framework allows for more definitive conclusions on the makeup and distribution of various intervention components in LMICs and within specific regions. This review also includes an emphasis on interrogating culture and adaptation, which is valuable given the importance of cultural understanding. Although there were a large number of non-randomised trials and pre/post studies, this review included a higher percentage of RCTs than previous reviews in LMICs, improving the overall quality of results.

One limitation was only including studies with full-texts in English or Spanish, the languages spoken of the author. The components reported here were selected based on criteria established through the framework synthesis, but detailed analysis of additional study characteristics would be useful and interesting. Additionally, studies without full-texts available were excluded and only two authors replied to full-text requests.

Core components were extracted and included only if they were explicitly reported in the publication and although authors were contacted whenever possible for further detail most did not reply. Additionally, more than half the studies were pre/post studies without a control group, increasing the possibility of bias and a quarter of studies were of poor or very poor quality. Regarding stigma reduction measures, although evidence surrounding knowledge gain as a proxy for stigma is mixed (Stuart, Reference Stuart2016), interventions solely measuring knowledge gain were included (n = 1) as per a reflection of the existing stigma literature. Further research is needed to understand what aspects of knowledge-based interventions impact stigma and how. The generalisability of the region-specific analysis was reduced by the fact that each region's studies were dominated by a single country. Finally, the small number of ineffective studies suggests that there may be publication bias in this area of research.

Implications and recommendations

The vast amount of extracted data for this review, organised into 106 detailed components, sub-components and elements, should provide other researchers with a useful starting point for designing and analysing mental health stigma reduction interventions.

Given that the majority of stigma research focuses on HICs, understanding what has worked in varied low-resource settings would be essential when developing effective stigma reduction interventions in LMICs, for example when using creative methods such as theatre, dance and web-based interventions.

More research needs to be conducted in a wider variety of countries, and interventions need to be developed using local expertise and be culturally adapted. Due to its proven effectiveness (Gronholm et al., Reference Gronholm, Henderson, Deb and Thornicroft2017), social contact should be actively incorporated into stigma reduction interventions.

Conclusion

This systematic review found many and varied stigma reduction programmes with effective intervention components in LMICs. Most included studies described interventions based on educational methods, along with themes of medical knowledge surrounding mental health, teaching emotional/communication skills, myth-busting, emphasising recovery and discussing the media's impact on stigma. Yet there are minimal descriptions of social contact, despite the fact that it has been shown to be the most impactful single component of stigma reduction work (Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Mehta, Clement, Evans-Lacko, Doherty, Rose, Koschorke, Shidhaye, O'Reilly and Henderson2016). This may be due to lack of knowledge about the state of evidence around contact interventions, lack of influence and opportunity for groups of people affected to be included, or stigma itself.

Although to date only a minority of studies were developed, evidenced or culturally adapted in the local setting, the overall quantity and quality of studies has increased over the past several years. If the best evidence was available to groups working to combat stigma globally, it is likely that the important benefits of these efforts to promote inclusion and reduce stigma and discrimination would be amplified, and more people in need would seek and get access to mental health care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000797

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sarah Devos and Thomas Elsmore for their help reviewing the data during the study selection phase.

Financial support

N.V. is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) (grant number ES/J500057/1) and the INDIGO Medical Research Council (MRC) Partnership Grant (grant number MR/R023697/1). The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. PCG is funded by the INDIGO Medical Research Council (MRC) Partnership Grant (grant number MR/R023697/1). MS is funded through the NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Neglected Tropical Diseases at the Brighton and Sussex Medical School, using Official Development Assistance (ODA) funding.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review, as confirmed in a letter from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Research Governance & Integrity Office dated 24 April 2019.

Availability of Data and Materials

For access to all data supporting this study, please email Jennifer Clay: jeclay3@gmail.com.