It is known that the most primitive impulses of man can arise through confinement. The most basic instincts are constantly manifested in various forms: from decorative impulses, to a variety of other creative representations. This phenomenon can be interpreted as a need of personalisation of their living space: writing and perpetuating existence within a place (Prinzhorn, Reference Prinzhorn2012). The art works of individuals with a mental illness can respond to an impulse of decorating, reaffirming their existence or occupational purposes. The art made by this population has provoked a debate since the 1930s: it has been censored by some regimes, while at the same time has been used to magnify the power of the state of unconsciousness (Peiry, Reference Peiry2001). Recurrent themes can be perceived in the drawings of people with mental illness under confinement, for example an excess of religious thought or childish regressions (Prinzhorn, Reference Prinzhorn2012). This article aims to observe the principal subjects on the drawings of Ezequiel, an individual diagnosed with schizophrenia who was confined in a penitentiary centre in Mexico. Around 250 drawings were collected and analysed, different characteristics of his creative process can be observed, and were classified as motifs, techniques, compositions and themes. To analyse the drawings, different study fields were considered; from art therapy assessment scales and creative process in outsider art to parameters in the intersection of psychiatry and art. The art therapy assessment scale FEATS was used to measure variables on the drawings as it has interrater reliability (Gantt and Tabone, Reference Gantt and Tabone2012). The studies of Lyle Rexer and Graciela Garcia were considered as they have developed theories to study the creative processes in outsider artists (García, Reference García2015; Rexer, Reference Rexer2005). Prominent studies from Hans Prinzhorn, Walter Morgenthaler and Leo Navratil were also considered because of their significance of observing parameters on the artwork made by individuals presenting schizophrenia (Prinzhorn, Reference Prinzhorn2012; Morgenthaler, Reference Morgenthaler1992; Navratil, Reference Navratil1972). The grounded theory coding principles guided the analysis of the data content where the drawings of the individual were analysed to generate subjective categories and patterns (Sayer, Reference Sayer2000; Kempster and Parry, Reference Kempster and Parry2011; Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2009). The significance of the following analysis relapses into integrating analytic frameworks in different related areas.

A main feature of Ezequiel's work is his creative drive, expressed through his preference for drawing and carving in rocks. Despite having selective mutism due to his psychiatric condition, he expresses his thoughts, concerns and memories through his drawings, which are frequently accompanied by short texts. At the penitentiary centre, he is known for selling everything for 50 cents. Other activities that Ezequiel is known for, is to provide water for everyone in the section of the penitentiary where he's located, a few times a day. He has several bird tattoos on his arms, animals which are also represented on his drawings; similarly, his fixation with the quantity ‘fifty cents’ can frequently be observed in his work.

Throughout history, some disciplines have had a particular way of cataloguing people who deviate from the norm: mystics can be considered crazy, saints are regarded as psychotic and wise people as schizophrenics (Belloc et al., Reference Belloc, Sandín and Ramos1995). Ezequiel is not an exception, he is perceived as a mystic figure by the other individuals at the penitentiary centre. For example, the fact that he refuses to eat food offered to him, and that he doesn't have any records of sickness during his years in confinement is seen as a supernatural ability of Ezequiel's by other prisoners. Just as a shaman brings hope to a tribe, the figure of Ezequiel seems to play the role of a guide; this can be recognised by the tendency of some of the people at the penitentiary centre to collect his drawings. In both cases, the work of these characters is fully integrated with their community, and they embody authority and mysticity, and receive the respect of their peers.

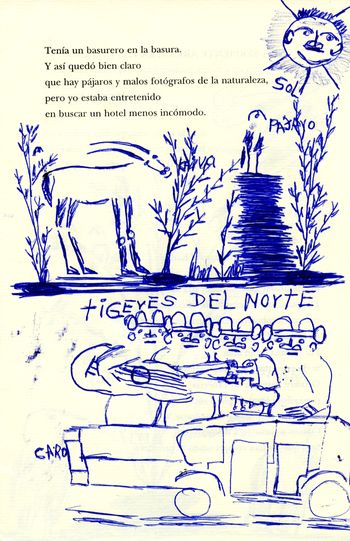

Surrealism and other artistic movements were strongly influenced by the research and theories developed by Hans Prinzhorn, as well as the collection developed by Jean Dubuffet (Danchin, Reference Danchin2006). The surrealists found a type of representation in the inclusion of diverse elements with enigmatic and symbolistic effect in their artistic productions; arrows, signs and loose letters were important components of their works (Navratil, Reference Navratil1972). Commonly, elements of the drawings of people with schizophrenia are not clearly related. Similarly, in Ezequiel's creative work, drawings with diverse elements that do not have a logical relation are frequently found: from cars on top of a person's head, to lose elements like numbers and objects next to anthropomorphic figures. The admiration of these attributes, naturally developed by this population, suggested they were the real surrealists.

Ezequiel's creative work is unsolicited and self-motivated, it is driven by the necessity of expression due to his incarceration. This is a characteristic constantly observed among outsider self-taught artists. It is common to find cases of people who were incarcerated for criminal acts, where the incarceration itself is the occasion – even the motive – of their art. In this sense, it might be said that their work is directly a product of their being held outside of their society (Rexer, Reference Rexer2005). In this context, Ezequiel work has similar motivations and recurrences.

He prefers to use pen and pencil for his work, and has an inclination towards reusing ‘canvases’: Ezequiel uses the empty spaces of books, magazines and other materials that he finds, mostly in the trash bin, to form his compositions. In his work, one can observe a tendency to fill most of the available blank space without any structural purpose, a characteristic known as horror vacui (fear of empty space). This is a common tendency in creations made by schizophrenics, as well as popular art expressions (García, Reference García2015). Horror vacui can be explained as an attribute that connects a moment and a space, it also gives the sense of starting a never-ending creative process.

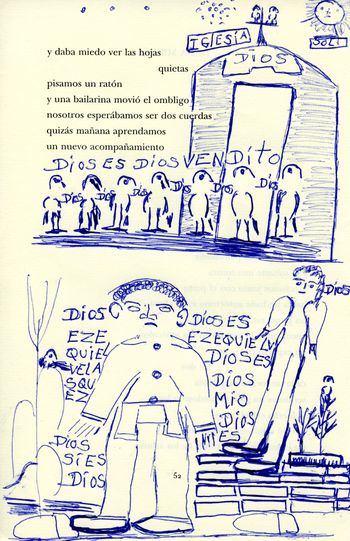

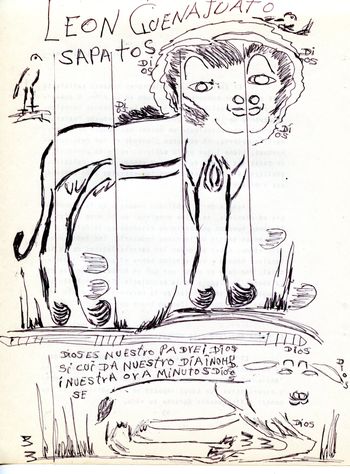

Entering Ezequiel's imaginary through his work, it's possible to observe different topics and types of representation: magical-religious thinking, multiplications, passages of this daily life, among others. The representation of his work is completely figurative; animals and plants are the most common topics (Figs 1 and 4), followed by human figures and elements from the sky. The animals represented in his drawings are anthropomorphised, have their sexual organs remarked, and are frequently accompanied by plants and elements of the weather on the represented scene. Zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures constantly show the same features, and the natural essence of some animals is exalted and glorified with phrases and words. Another particularity when representing animals and human figures is that they tend to lack an outline around their faces. Self-portraits are a recurrent theme in his work, and frequently include his name (Fig. 3). The creation of an image of the self can suggest an attempt to step back from a past experience and to reflect on the process leading to the present (Alter Muri, Reference Alter Muri2007).

Fig. 1. “Tigres del norte” drawing of traditional Mexican music group.

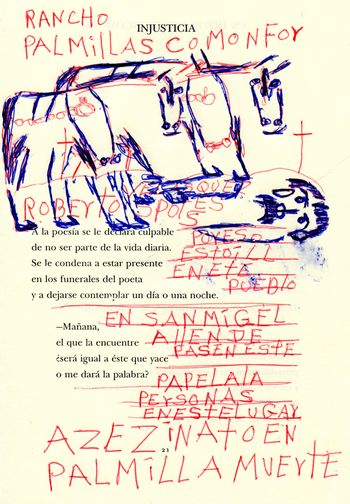

Another important theme on his artwork is the murder he committed (Fig. 2), the cause for which he is at the penitentiary centre. In four of the collected works, the crime scene is represented; these works explain different pieces of information and feelings linked to the experience, and give a sense of confession and regret. An enigmatic representation has a relation with the mood of the person (Navratil, Reference Navratil1972). These type of drawings on Ezequiel's artwork are constantly filled with text and have a strong emotional charge. Phrases such as ‘God does not want dark devils’ and ‘that is the reason I am here’ constantly appear on these kinds of drawings.

Fig. 2. Drawing about the murder.

The word ‘God’ is constantly observed in different parts of his work: phrases such as ‘God is a donkey’, ‘God is a goat’ and ‘God is Ezequiel’ (Fig. 3) are handwritten in his drawings. Plants and elements from the sky are commonly represented and referred to as God. Ezequiel's inclination for divine figures and enigmatic motives is shown in his drawings, as well as the content of his texts. Depictions of saints, the virgin Mary, Jesus, prayers and some biblical passages frequently appear in his work. When the figures and letters are no longer expressions of an original regulatory effort, but not yet rational symbols, they have something of the enigmatic character (Navratil, Reference Navratil1972). The intense loss of relationship between the elements and stylisation of his drawings is counteracted by the intensity and the content, serial and composition, as well as the inclusion of letters.

Fig. 3. Representation of birds going to the church and self portrait with the legend “Ezequiel is God”.

Fig. 4. Drawing of the region of Guanajuato with a prayer.

Ezequiel's work may not be technically outstanding, but its content may lead us to understand the complexity of being under-confident, having a mental illness, as well as life and experiences in jail. This situation comes along with a radical isolation and can lead to an altered consciousness. The themes he uses in his drawings are singular due to his context, and it can relate to a magical-religious thinking frequently observed in people with similar conditions. However, the question inevitably appears, as to whether he would have ever channelled his creative energy into art, if the current life restrictions he faces would not have occurred.

About the author

Ana Karen Gonzalez Barajaz is a PhD student at the Department of Social Work and Social Administration in the University of Hong Kong. She has been working on research Outsider Art, principally in Mexico. She is part of the directive committee of the Outsider Art magazine Bric-à-Brac. She conducts social inclusion art-based workshops for women and children in rural communities and people with behavioural, developmental, psychological and cognitive disorders.

Prof. Rainbow Tin Hung Ho, PhD, BCDMT, AThR, REAT, RSMT, CGP, CPA, is the Professor of the Department of Social Work and Social Administration, Director of the Centre on Behavioural Health and the Master of Expressive Arts Therapy programme in the University of Hong Kong. She has been working as a researcher, professor, creative arts therapist, dance teacher and performer for many years. She has published extensively in refereed journals, scholarly books and encyclopaedia, and has been the principal investigator of many research projects related to creative and expressive arts therapy, mind-body medicine, psychophysiology, spirituality, and physical activity for healthy and clinical populations.

Carole Tansella, Section Editor