Introduction

The recent refugee crisis and migratory waves have been the focus of much political attention in high-income countries (Gianfreda, Reference Gianfreda2018). A major area of debate has been how to address the health needs of the high numbers of new individuals coming into a country in a short timeframe (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016).

Refugees’ mental health needs have been a particular concern. Specifically, the factors which may lead to refugees’ migration, i.e. exposure to political persecution and war (UNHCR, 2019) can also predispose them to mental disorders (WHO, 2018).

This gave impetus to the research in this field and a number of studies have assessed prevalence rates in different groups of asylum seekers and refugees and for different mental disorders (e.g. Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016; Turrini et al., Reference Turrini, Purgato, Ballette, Nosè, Ostuzzi and Barbui2017; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018).

However, when assessing prevalence rates of mental disorders in these groups, a number of problems may arise, which are reflected by a high heterogeneity in prevalence rates across studies (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016; Giacco and Priebe, Reference Giacco and Priebe2018; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018). These problems are usually summarised as follows:

(a) There are pragmatic challenges in carrying out epidemiological studies in these groups, such as language barriers, lack of validity of research tools across different cultures (Lewis-Fernandez and Aggarwal, Reference Lewis-Fernández and Aggarwal2013; Brisset et al., Reference Brisset, Leanza, Rosenberg, Vissandjée, Kirmayer, Muckle, Xenocostas and Laforce2014; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Matanov and Priebe2014) and difficulties in accessing some individuals or groups (Enticott et al., Reference Enticott, Shawyer, Vasi, Buck, Cheng, Russell, Kakuma, Minas and Meadows2017); these challenges may lead to bias within studies and methodological artefacts;

(b) There are differences among individuals and groups of asylum seekers and refugees based on different personal backgrounds, as well as differing social situations in home countries and host countries (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018).

The challenges in achieving representative samples can be overcome to some extent by technical safeguards such as using well-trained interpreters or same language interviewers, adopting culturally validated instruments and using carefully designed sampling techniques.

The individual or group differences across asylum seekers and refugees are, instead, true, not influenced by methodology, and, as such, generate unavoidable heterogeneity across studies.

However, there is a third type of problems, which have received less attention from the epidemiological research so far. The statuses of asylum seekers and refugees are determined by legal frameworks and procedures and are transitory in nature. They do not identify stable categories, with which rates of mental disorders can be reliably associated.

These changing statuses can be summarised as follows. All refugees are initially classed as asylum seekers (UNHCR, 2019). The process of obtaining asylum and refugee status can last a long time. During this time, they have the right to remain in the host country but are uncertain as to whether their application will be approved. If the asylum application is not approved, they can leave that country (and move to another country), appeal or become irregular migrants. The refugee status can also be revoked (‘cessation of their refugee status’) (Kapferer, Reference Kapferer2003) once a host country court rules that the causes of political persecution or lack of safety (e.g. wars, political regimes, etc.) have ceased in the refugees’ home countries.

So far, refugees, asylum seekers and people who do not have a recognised immigration status in a new country have usually been pooled together in research studies and meta-analyses. This may lead us to ignore differences in stressors which may have a considerable impact on a person's mental health.

The usual stratification of risk factors for mental health is based on a simplified framework in which refugees encounter pre-, peri- and post-migration factors (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018). This has not influenced sampling for epidemiological studies as these studies are usually carried out in the host countries (i.e. post-migration).

Aims

This study aimed to carry out a systematic review of the evidence on risk and protective factors for the mental health of asylum seekers, refugees and in general of people who have been forcibly displaced from their countries. We then sought to classify these factors according to different stages in the life before migration, migration journey and resettlement of these people, with a particular attention to the increasing evidence on post-migration factors (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016; Miller and Rasmussen, Reference Miller and Rasmussen2017).

Methods

Design

This study is a systematic review with a narrative synthesis of the findings.

Previous literature reviews appraised the evidence on risk and protective factors for refugees’ and asylum seekers’ mental health until January 2017 (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018).

A systematic search of the evidence was carried out from January 2017 to August 2019 in order to provide the most updated findings. It used similar inclusion criteria but a simplified search strategy and did not include grey literature. This is because our previous reviews were also interested in identifying interventions and good practices, which are often found in other types of documents and sources. The current study, instead, was specifically focused on risk and protective factors for mental health, for which we are aware that an adequate amount of evidence is available in the scientific peer-reviewed literature. Focusing on peer-reviewed literature also ensured that sufficient quality standards were adhered to by all included papers.

Paper identification and selection

The search words used were the following: (‘refugee’ OR ‘asylum seeker’ OR ‘irregular migrant’ OR ‘undocumented migrant’) AND (‘mental health’) AND (‘risk factors’ OR ‘correlates’). EMBASE, PsychINFO and OVID Medline databases were searched.

Papers were included if: (a) at least 50% of the research participants were refugees and/or asylum seekers; (b) they assessed risk or protective factors for mental disorders; (c) they focused on adult populations (18 or older years of age); (d) they reported on studies carried out in high-income countries (according to the World Bank Classification); (e) they reported on primary research or were literature reviews, excluding opinion pieces; (f) they were published in full articles or full reports in scientific journals, excluding grey literature and conference presentations.

Papers were excluded if they focused only on aspects other than risk and protective factors for mental disorders, e.g. interventions, prevalence rates without correlates, individuals’ experience of care or barriers to access care. Qualitative studies which described patients’ or clinicians’ views about which were potential risks or potential factors for mental health were also excluded. They were deemed as ‘non-focusing on risk and protective factors for mental health’ given that they failed to demonstrate the actual association of those factors with mental health, only suggesting that this may be.

Procedures and analysis

From each paper identified, risk and protective factors were captured and summarised in an excel extraction table.

The risk and protective factors identified from different studies were initially grouped together according to when they occurred, based on the usual framework (pre-, peri- and post-migration).

The analysis then continued with the aim of re-grouping risk and protective factors in more specific and discrete time points which generated the final time points described in the Results section.

Results

Our search identified 252 papers in the period January 2017–August 2019. After removal of duplicates and screening according to inclusion criteria, 31 papers were included, i.e. 28 papers reporting on primary research and three literature reviews.

The PRISMA diagram can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

The main characteristics of the included studies are synthesised in Table 1.

Table 1. Details of the included studies (N = 31)

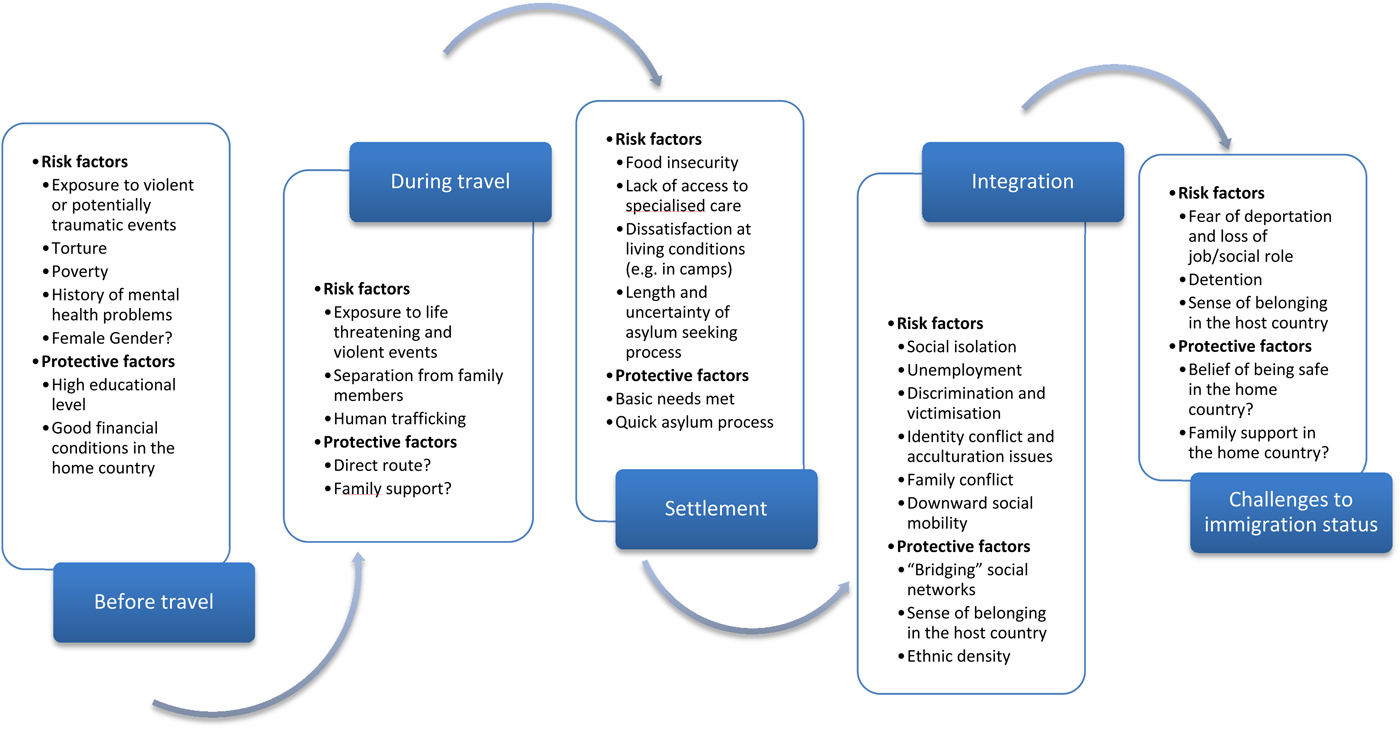

Five time points were identified, in which all the risk and protective factors identified can be categorised. These time points are: (a) before travel; (b) during travel; (c) initial settlement in the host country; (d) integration in the host country; (e) challenges to or revocation of the immigration status.

A summary of risk and protective factors at all of these time points can be found in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Critical time points for the mental health of asylum seekers and refugees and risk and protective factors at play.

These different time points can all be experienced by individuals who are forced to migrate from their countries. However, this is not necessarily the case for all of these individuals. For example, some of them may have their asylum applications rejected and never reach the status of a refugee. Others may integrate successfully and, hence, remain in the host country as naturalised citizens without their residence status being challenged.

Before travel

Exposure to potentially traumatic events (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hall, Ling and Renzaho2017a; Myhrvold and Småstuen, Reference Myhrvold and Småstuen2017; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018; Hynie, Reference Hynie2018; Kartal et al., Reference Kartal, Alkemade, Eisenbruch and Kissane2018; Park et al., Reference Park, Lee and Jun2018), violent events witnessed or experienced (Ben Fahrat et al., Reference Ben Farhat, Blanchet, Juul Bjertrup, Veizis, Perrin, Coulborn, Mayaud and Cohuet2018; Kaltenbach et al., Reference Kaltenbach, Schauer, Hermenau, Elbert and Schalinski2018, Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Vromans, Brough, Asic-Kobe, Correa-Velez, Murray and Lenette2018; Rees et al., Reference Rees, Fisher, Steel, Mohsin, Nadar, Moussa, Hassoun, Yousif, Krishna, Khalil, Mugo, Tay, Klein and Silove2019) and particularly being subjected to torture (Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Schick, Schnyder, Bryant and Morina2017; Le et al., Reference Le, Morina, Schnyder, Schick, Bryant and Nickerson2018; Song et al., Reference Song, Subica, Kaplan, Tol and De Jong2018) have all been linked to high likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress disorder and other forms of psychological distress. This is more likely if the experience of torture is accompanied by intense emotions of anger, fear and perceived uncontrollability (Le et al., Reference Le, Morina, Schnyder, Schick, Bryant and Nickerson2018). The risk of developing a mental disorder also increases if a person is exposed to multiple potentially traumatic events and/or if post-migration adversities occur in addition to traumatic events before migration (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hall, Ling and Renzaho2017a; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Park2017; Nickerson et al., Reference Nickerson, Schick, Schnyder, Bryant and Morina2017; Tinghög et al., Reference Tinghög, Malm, Arwidson, Sigvardsdotter, Lundin and Saboonchi2017; Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018; Kartal et al., Reference Kartal, Alkemade, Eisenbruch and Kissane2018; Nosè et al., Reference Nosè, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Sangalang et al., Reference Sangalang, Becerra, Mitchell, Lechuga-Peña, Lopez and Kim2018; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Vromans, Brough, Asic-Kobe, Correa-Velez, Murray and Lenette2018; Song et al., Reference Song, Subica, Kaplan, Tol and De Jong2018).

As well as traumatic events, exposure to economic hardship and social deprivation in home countries and a history of mental health problems before migration can predict mental disorders after settlement in host countries (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hatch, Comacchio and Howard2017; Giacco and Priebe, Reference Giacco and Priebe2018).

On the other hand, having experienced good financial conditions and having attained a higher level of education in the home country are associated with reduced rates of mental disorders after migration (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Park2017; WHO, 2018).

Some studies have found that female gender is associated with a higher likelihood of presenting clinically significant mental health symptoms in asylum seekers and refugees (Poole et al., Reference Poole, Hedt-Gauthier, Liao, Raymond and Barnighausen2018; Song et al., Reference Song, Subica, Kaplan, Tol and De Jong2018; Mulugeta et al., Reference Mulugeta, Xue, Glick, Min, Noe and Wang2019). However, most studies did not identify differences across genders (see Table 1).

During travel

Refugees travel through dangerous land routes or via sea and can be exposed to violent events or abuse during their journey. Exposure to violent events during migration (Ben Fahrat et al., Reference Ben Farhat, Blanchet, Juul Bjertrup, Veizis, Perrin, Coulborn, Mayaud and Cohuet2018; Poole et al., Reference Poole, Hedt-Gauthier, Liao, Raymond and Barnighausen2018) and to human trafficking (Ottosova et al., Reference Ottisova, Hemmings, Howard, Zimmerman and Oram2016; WHO, 2018) have been linked with poor mental health after resettlement. Separation from family members as part of the migration or during the migration (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hess, Bybee and Goodkind2018) also has been found to have negative consequences on mental health.

There are no studies which have explored protective factors during migration. However, it is likely that travelling through less dangerous or more direct routes and having the support of family members or trusted friends during the travel is associated with less stress and impact on mental health.

Settlement in a host country

The risk factors encountered in the first period after settlement in a host country are related to food insecurity, lack of accommodation (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Merry and Gagnon2017; Song et al., Reference Song, Subica, Kaplan, Tol and De Jong2018) and dissatisfaction with accommodation, particularly in refugee camps (Poole et al., Reference Poole, Hedt-Gauthier, Liao, Raymond and Barnighausen2018). A longer duration of the asylum seeking process and lack of information can generate prolonged stress and uncertainty which was found to be associated with clinically relevant psychological symptoms (Ben Fahrat et al., Reference Ben Farhat, Blanchet, Juul Bjertrup, Veizis, Perrin, Coulborn, Mayaud and Cohuet2018; Poole et al., Reference Poole, Hedt-Gauthier, Liao, Raymond and Barnighausen2018).

Better conditions of settlement, access to health care (Dennis et al., Reference Dennis, Merry and Gagnon2017) and a prompter and/or smoother process for obtaining a residence status can have a positive impact on the mental health of refugees (Müller et al., Reference Müller, Zink and Koch2018; Kashyap et al., Reference Kashyap, Page and Joscelyne2019). The uncertainty related to asylum decisions is a factor which has been found to be consistently associated with poor mental health in a number of studies (Ben Fahrat et al., Reference Ben Farhat, Blanchet, Juul Bjertrup, Veizis, Perrin, Coulborn, Mayaud and Cohuet2018; Leiler et al., Reference Leiler, Bjärtå, Ekdahl and Wasteson2019; Hvidtfeldt et al., Reference Hvidtfeldt, Petersen and Norredam2019).

Integration in a host country

Prevalence studies show higher rates of mental disorders (particularly anxiety and depressive disorders) in long-term resettled refugees (at least 5 years) than in those at first resettlement (Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015). Recent studies have also shown that an increased length of displacement can be associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing mental disorders (Hynie, Reference Hynie2018; Nosé et al., Reference Nosè, Turrini, Imoli, Ballette, Ostuzzi, Cucchi, Padoan, Ruggeri and Barbui2018; Mulugeta et al., Reference Mulugeta, Xue, Glick, Min, Noe and Wang2019).

During the process of integration in the host country, risk factors for mental health can be social isolation (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hatch, Comacchio and Howard2017; Beiser and Hou, Reference Beiser and Hou2017; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hall, Ling and Renzaho2017a; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Park2017; Hynie, Reference Hynie2018; Schweitzer et al., Reference Schweitzer, Vromans, Brough, Asic-Kobe, Correa-Velez, Murray and Lenette2018), unemployment (Kaltenbach et al., Reference Kaltenbach, Schauer, Hermenau, Elbert and Schalinski2018), discrimination and victimisation (Sangalang et al., Reference Sangalang, Becerra, Mitchell, Lechuga-Peña, Lopez and Kim2018), struggles related to their cultural identity and acculturation issues (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ling and Renzaho2017b; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Park2017) and downward social mobility (Euteneuer and Schafer, Reference Euteneuer and Schäfer2018).

A protective factor for mental health is having ‘bridging social networks’ (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ling and Renzaho2017b; Beiser and Hou, Reference Beiser and Hou2017), i.e. social networks including people from different ethnic groups. Developing a sense of belonging in the host country was also found to be associated with reduced likelihood of mental disorders (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ling and Renzaho2017b; Myhrvold and Småusten, Reference Myhrvold and Småstuen2017; Beiser and Hou, Reference Beiser and Hou2017) and so were positive changes in post-migration living arrangements (Shick et al., Reference Schick, Morina, Mistridis, Schnyder, Bryant and Nickerson2018). In particular, achieving a visa or resident status was associated with better response to treatment (Schick et al., Reference Schick, Morina, Mistridis, Schnyder, Bryant and Nickerson2018). Findings also suggest that refugees living in areas where there is a high number of people from their own ethnic group, i.e. a high ‘ethnic density’ may be less likely to use mental health services and hence less likely to present severe mental health needs (Finnvold and Ugreninov, Reference Finnvold and Ugreninov2018). In accordance with this, a larger household size was found to be a protective factor for mental health (Yang and Mutchler, Reference Yang and Mutchler2019).

Immigration status challenged or revoked

At this time point, threats of deportation, detention in immigration centres and losing jobs or accommodation are recognised risk factors for psychological distress and diagnosable mental disorders (Priebe et al., Reference Priebe, Giacco and El-Nagib2016; Kashyap et al., Reference Kashyap, Page and Joscelyne2019). A sense of belonging in the host country, which is a protective factor during integration, can become a risk factor if the immigration status is challenged (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Park2017).

No studies have assessed protective factors when immigration status is challenged or revoked. It might be expected that a sense of being safe in the home country, having a family or a social network there and maintaining a strong sense of belonging to the home country may be protective against psychological distress (whilst ‘affiliative feelings towards the home country’ can be a risk factor for mental health during the process of integration in the host country, as found in Beiser and Hou, Reference Beiser and Hou2017).

Discussion

Main findings

This review has identified five time points at different stages of the migration process of asylum seekers and refugees in which different risk and protective factors may occur. The time points identified go beyond the usual and simplified distinction of pre-migration, peri-migration and post-migration risk factors and constitute a more comprehensive categorisation.

Implications

The risk and protective factors identified have all been variably described in previous studies (Lindencrona et al., Reference Lindencrona, Ekblad and Hauff2008; Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Ajdukovic, Bremner, Franciskovic, Galeazzi, Kucukalic, Lecic-Tosevski, Morina, Popovski, Schützwohl, Wang and Priebe2012; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015). This study adds a novel categorisation with five distinct time points in which risk and protective factors can be encountered by refugees after migration. Despite the increased complexity of this categorisation, it may have a number of advantages as a framework for research, psychosocial assessment and selection of interventions.

First, this more comprehensive categorisation may help in interpreting the heterogeneity of prevalence studies (Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015; WHO, 2018). It can provide a useful way of stratifying research participants in more homogeneous groups with regards to risk and protective factors for their mental health, and these groups may show more similar prevalence rates of mental disorders.

Second, the risk and protective factors identified can be a target of interventions aiming to address or foster them in prevention and treatment programmes specifically provided at different time points.

Third, it is important to observe that some factors may act as either risk or protective factors depending on the different time points. For example, sense of belonging in the host country is a protective factor during integration (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ling and Renzaho2017b; Myhrvold and Småusten, Reference Myhrvold and Småstuen2017; Beiser and Hou, Reference Beiser and Hou2017), but a risk factor in case of immigration status being challenged or revoked (Geraci (Reference Geraci2011) and Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee and Park2017). Similarly, affiliative feelings towards the home country can be a source of anxiety during migration, settlement or integration in the host country (Beiser and Hou, Reference Beiser and Hou2017), but are likely to represent a protective factor in case of the possibility of repatriation. Interventions and psychosocial assessments should take the variation in the role of these factors into account.

Finally, decision making about the type of interventions to prevent or alleviate psychological distress can be informed by the critical time points identified. Addressing basic needs and accommodation problems may be more important and effective during the first resettlement than embarking in complex psychological or pharmacological interventions. If the immigration status is challenged or revoked, supportive interventions to understand and address concerns and fears about repatriation or to help people plan their return may be provided, particularly if deportation is inevitable (Geraci, Reference Geraci2011). Standard psychiatric interventions may not address these specific concerns and be ineffective, if such fears are a core reason for anxiety or disturbances in mood.

Limitations

The following limitations need to be acknowledged:

(a) our findings are based on an appraisal of research studies. These studies may not have been able to reach people who face barriers to access mental health services or research teams (Enticott et al., Reference Enticott, Shawyer, Vasi, Buck, Cheng, Russell, Kakuma, Minas and Meadows2017);

(b) the effect of risk and protective factors on rates of mental disorders were not analysed quantitatively using a meta-analysis. Hence we are unable to speculate on which of them has the highest effect on mental health and should be prioritised. However, a meta-analysis of individual risk factors was carried out previously, reporting high heterogeneity and variable methodological quality of the included studies (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Chey, Silove, Marnane, Bryant and van Ommeren2009). In this study, the aim was to identify when risk and protective factors are likely to occur and this can also be of importance for planning treatments and prevention strategies.

(c) a general consideration of risk factors, pooling all mental disorders together, is likely to emphasise risk factors for the most frequently diagnosed disorders (e.g. anxiety and depressive disorders) with less of a focus on the factors associated to disorders with comparatively lower prevalence rates (e.g. psychotic disorders, somatisation disorders, etc.) (Giacco et al., Reference Giacco, Laxhman and Priebe2018).

(d) low- and middle-income countries were excluded because it was felt that examining the risk and protective factors for mental health in these countries would justify a specific review study. There is an increasing amount of studies exploring the mental health of asylum seekers and refugees in low- and middle-income countries. Twenty-three papers have been written in this area in the last two and a half years and had to be excluded from this review (see Fig. 2). Moreover, in low- and middle-income countries, additional factors might intervene which may complicate the categorisation proposed. A particular issue is that some of these countries can be deemed as ‘transit countries’. Migrants expect to only spend some time in transit countries in preparation of reaching the planned final destinations. Recent studies have found high rates of mental disorders in transit countries (Arsenijevic et al., Reference Arsenijevic, Schillberg, Ponthieu, Malvisi, Ahmed, Argenziano, Zamatto, Burroughs, Severy, Hebting, de Vingne, Harries, Beiser and Hou2017; Vukčević Marković et al., Reference Vukčević Marković, Gašić and Bjekić2017; WHO, 2018) and specific studies are required to understand in detail why this is. Moreover, a difficult financial situation in the host country might make the process of integration of refugees even more difficult and challenging.

Suggestions for future research

There are a number of unresolved questions in this area, which may be addressed by future research.

All refugees, by definition, have been exposed to stressful events such as political persecution, war and/or torture (UNHCR, 2019). Yet, many of them will not present with diagnosable mental disorders. Future studies should focus on understanding how these individuals are able to show such resilience and use the mechanisms and factors underlying resilience to inform interventions.

With regard to high-income countries, there is a need to better understand the potential selection processes which may occur during migration (WHO, 2018). There may be differences in socio-demographic characteristics among refugees who migrate to high-income countries and those who stay in the home country or migrate to other poorer or nearer countries. Selection processes may also occur between people who stay for a longer time in a given host country and those who leave that country after a shorter period of time.

Finally, understanding the impact of changing social contexts and political climates on the equilibrium between post-migration risk and protective factors may need to be in the research agenda too. Increasing negative (or, on the other hand, positive) social attitudes in host countries may influence the level of discrimination that refugees encounter, the investment in social integration programmes and the opportunities for refugees to flourish. This, in turn, could have a negative impact on asylum seekers’ and refugees’ mental health. Interventions provided within mental health services may not be able to address these issues on their own.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the help of Miss Maev Conneely-McInerney and Miss Megan Patterson with the editing of this manuscript during its preparation and revision. No other people have actively contributed to the present manuscript. However, I would like to thank the experts involved in the development of technical guidance on ‘mental health promotion and mental health care in refugees and migrants’ (WHO, 2018). This paper is indebted to the inspiring conversations and the intellectual stimulation received during the meetings of that project. Nevertheless, I should clarify that they did not directly influence the specific design and methodological choices made for this paper and that the opinions and views expressed in this manuscript are purely those of the author.

Financial support

The author did not receive any specific funding for this work.

Conflict of interest

None.