Introduction

Patients and clinicians can benefit from prognostic information (Hayden et al., Reference Hayden, Van Der Windt, Cartwright, Côté and Bombardier2013). Such knowledge can inform routine clinical assessments and triages of patients seeking treatment for depression and might guide the collaborative treatment decision-making process. This information does not help determine which treatment may be most likely to benefit any individual patient, but instead, informs considerations of the intensity, dose or duration of treatment, the regularity of progress reviews and referrals to specialist treatment centres (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021). This would be particularly true if the differences in prognoses for patients with one compared to another pre-treatment characteristic were of a clinically important magnitude (Button et al., Reference Button, Kounali, Thomas, Wiles, Peters, Welton, Ades and Lewis2015). Prognostic information is often wanted by patients and clinicians (Trusheim et al., Reference Trusheim, Berndt and Douglas2007). However, prognostication for adults with depression is challenging as most prior studies have considered prognosis following one particular type of treatment, or in samples where either no treatment was given or details regarding any treatment(s) are unknown (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, White, Lewis and Pilling2020; Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021). As there is an approximate equivalence (on average) in the effectiveness of the most common types of treatment for depression (Menchetti et al., Reference Menchetti, Bortolotti, Rucci, Scocco, Bombi and Berardi2010; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Hollon, van Straten, Bockting, Berking and Andersson2013; Weitz et al., Reference Weitz, Kleiboer, Van Straten, Hollon and Cuijpers2017; Cipriani et al., Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Chaimani, Atkinson, Ogawa, Leucht, Ruhe, Turner, Higgins, Egger, Takeshima, Hayasaka, Imai, Shinohara, Tajika, Ioannidis and Geddes2018), and a number of prognostic factors have been found to be associated with outcomes from one type of treatment but not others (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Berk, Kelin, Zhang, Eriksson, Deberdt and Craig Nelson2014; Chekroud et al., Reference Chekroud, Zotti, Shehzad, Gueorguieva, Johnson, Trivedi, Cannon, Krystal and Corlett2016; Nakabayashi et al., Reference Nakabayashi, Hara and Minami2018; Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021), there is a need to study prognosis regardless of the type of treatment received. Doing so would identify factors that are associated with prognosis in general, which would be informative for clinicians assessing and treating patients with depression in a breadth of settings. We call this prognosis independent of treatment. This form of prognosis has been largely overlooked in studies of depression (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, White, Lewis and Pilling2020; Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021). We recently found that a number of clinical factors were associated with prognosis independent of treatment, and that each contributed to explaining prognosis over and above depressive symptom severity (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021). We termed these depressive ‘disorder characteristics’. These were: the durations of depression and anxiety problems, comorbid panic disorder and a history of antidepressant medication, each should be routinely assessed in clinic alongside depressive symptom severity. Whether other factors are similarly associated with prognosis and add incremental value to prognostic assessments is uncertain.

For decades it has been shown that age, gender and marital status are associated with the prevalence of depression (Ensel, Reference Ensel1982; Kessler and Essex, Reference Kessler and Essex1982; Bebbington, Reference Bebbington1987; Faravelli et al., Reference Faravelli, Alessandra Scarpato, Castellini and Lo Sauro2013). Previous reviews of the relationship between these factors and post-treatment prognosis have found inconsistent results. For example, three reviews reported that older age was associated with worse prognosis (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Huibers2018; Nakabayashi et al., Reference Nakabayashi, Hara and Minami2018; Sockol, Reference Sockol2018); two found no such association (Johnsen and Friborg, Reference Johnsen and Friborg2015; Karyotaki et al., Reference Karyotaki, Riper, Twisk, Hoogendoorn, Kleiboer, Mira, Mackinnon, Meyer, Botella, Littlewood, Andersson, Christensen, Klein, Schröder, Bretón-López, Scheider, Griffiths, Farrer, Huibers, Phillips, Gilbody, Moritz, Berger, Pop, Spek and Cuijpers2017); and one found that prognosis improved with increasing age (Noma et al., Reference Noma, Furukawa, Maruo, Imai, Shinohara, Tanaka, Ikeda, Yamawaki and Cipriani2019). Similarly, four reviews reported that women had poorer prognoses than men (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Cantrell, Zarotsky, Haynes, Phillips, Alatorre, Goetz, Paczkowski and Marangell2012; Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Berk, Kelin, Zhang, Eriksson, Deberdt and Craig Nelson2014; Johnsen and Friborg, Reference Johnsen and Friborg2015; Noma et al., Reference Noma, Furukawa, Maruo, Imai, Shinohara, Tanaka, Ikeda, Yamawaki and Cipriani2019), while four reported no such association (Karyotaki et al., Reference Karyotaki, Riper, Twisk, Hoogendoorn, Kleiboer, Mira, Mackinnon, Meyer, Botella, Littlewood, Andersson, Christensen, Klein, Schröder, Bretón-López, Scheider, Griffiths, Farrer, Huibers, Phillips, Gilbody, Moritz, Berger, Pop, Spek and Cuijpers2017; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Karyotaki, Reijnders and Huibers2018; Nakabayashi et al., Reference Nakabayashi, Hara and Minami2018; Schoemaker et al., Reference Schoemaker, Kilian, Emsley and Vingerhoets2018). Two reviews reported better prognoses for married individuals (Carter et al., Reference Carter, Cantrell, Zarotsky, Haynes, Phillips, Alatorre, Goetz, Paczkowski and Marangell2012; Sockol, Reference Sockol2018) while a third found no evidence for this association (Karyotaki et al., Reference Karyotaki, Riper, Twisk, Hoogendoorn, Kleiboer, Mira, Mackinnon, Meyer, Botella, Littlewood, Andersson, Christensen, Klein, Schröder, Bretón-López, Scheider, Griffiths, Farrer, Huibers, Phillips, Gilbody, Moritz, Berger, Pop, Spek and Cuijpers2017).

There are clear limitations, most of these past studies are not directly comparable as the reviews examined specific treatments only (e.g., duloxetine or Interpersonal Psychotherapy), and the sample settings were unclear or unstated. None of the past reviews presented results adjusted for the effects of multiple known clinical prognostic factors (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021). To do so accurately, for factors that differ at the individual patient level requires individual patient data (IPD) (Rothwell, Reference Rothwell2005; Fisher, Reference Fisher2015) and only four of the past reviews had IPD. Two were not systematic reviews and made no adjustment for any clinical factors (Nakabayashi, Hara and Minami, Reference Nakabayashi, Hara and Minami2018; Noma et al., Reference Noma, Furukawa, Maruo, Imai, Shinohara, Tanaka, Ikeda, Yamawaki and Cipriani2019). Two others adjusted for baseline depressive symptom severity (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Berk, Kelin, Zhang, Eriksson, Deberdt and Craig Nelson2014; Karyotaki et al., Reference Karyotaki, Riper, Twisk, Hoogendoorn, Kleiboer, Mira, Mackinnon, Meyer, Botella, Littlewood, Andersson, Christensen, Klein, Schröder, Bretón-López, Scheider, Griffiths, Farrer, Huibers, Phillips, Gilbody, Moritz, Berger, Pop, Spek and Cuijpers2017). The first (Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Berk, Kelin, Zhang, Eriksson, Deberdt and Craig Nelson2014) made no adjustments for between-study effects and no assessments of either attrition or heterogeneity, limiting the robustness and interpretability of the findings. The second was an investigation of potential moderators of treatment effects and found high levels of heterogeneity that could not be explained (Karyotaki et al., Reference Karyotaki, Riper, Twisk, Hoogendoorn, Kleiboer, Mira, Mackinnon, Meyer, Botella, Littlewood, Andersson, Christensen, Klein, Schröder, Bretón-López, Scheider, Griffiths, Farrer, Huibers, Phillips, Gilbody, Moritz, Berger, Pop, Spek and Cuijpers2017). Clarity on the association of these factors with prognosis is needed, particularly for patients initially seeking treatment in primary care as large proportions of adults are either initially screened and assessed or are wholly treated for depression in primary care settings (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha2016; Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Blanco and Marcus2016; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Borges, Bruffaerts, Bunting, De Almeida, Florescu, De Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, Hinkov, Karam, Kawakami, Lee, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, De Galvis and Kessler2017).

Given these contrasting results, we aimed to determine whether age, gender and marital status are associated with prognosis for adults with depression who sought treatment in primary care. We investigated these associations after accounting for the effect of known clinical prognostic factors, the depressive ‘disorder characteristics’ we identified previously (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021), and regardless of the type of treatment. In so doing, we aimed to determine whether these factors add incrementally to knowledge of prognosis at the point patients initially seek treatment.

Methods

This systematic review with IPD meta-analysis is reported in accordance with the PRISMA-IPD statement (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Clarke, Rovers, Riley, Simmonds, Stewart and Tierney2015) (checklist in online Supplementary materials).

Identification and selection of studies

A protocol for this study was pre-registered (https://osf.io/e5zup/). A general protocol for forming the Depression in General Practice (Dep-GP) IPD dataset and the plan for analysing those data (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, White, Lewis and Pilling2020) and pre-registered methods for identifying studies are also available (PROSPERO: CRD42019129512 (01/04/2019)), and were reported in accordance with the PRISMA-P statement (Shamseer et al., Reference Shamseer, Moher, Clarke, Ghersi, Liberati, Petticrew, Shekelle and Stewart2015). Searches have been reported in accordance with PRISMA-S (Rethlefsen et al., Reference Rethlefsen, Kirtley, Waffenschmidt, Ayala, Moher, Page and Koffel2021), with a brief description below and more details provided in online Supplementary Materials.

Searches were conducted on Medline, Embase, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, PsycINFO and Cochrane Central (searched from inception to 1st December 2020), we also hand-searched reference lists, and contacted experts for unpublished or missed studies. Search terms included variations of phrases such as ‘depression’ or ‘major depression’, ‘RCT’ or ‘Randomised Controlled Trial’ and ‘CIS-R’ or ‘Clinical Interview Schedule’. See online Supplementary Table 1 for a full list and results of the searches.

A single reviewer (JB) screened titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies, these were then read in full and judged against inclusion/exclusion criteria by two reviewers (JB and GL) with consultation with a third (SP) to resolve any uncertainties by consensus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were RCTs of adults (aged 16 or over) with unipolar depression, depressive symptoms significant enough to seek treatment, or a Revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R) (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Pelosi, Araya and Dunn1992) score of ⩾12 (the cut-off for common mental disorder); recruited from primary care; had at least one active treatment arm; used the CIS-R at baseline, and assessed marital status, age and gender at baseline.

Studies were excluded if they: included patients with depression secondary to a diagnosis of personality disorder, psychotic conditions or neurological conditions; were studies of adults with bi-polar or psychotic depressions; were studies of children or adolescents; were feasibility studies; were studies of just one gender, one particular age group or one marital status group only.

Data extraction

The included studies are detailed in Table 1. Data were extracted for each study participant on all measures included in Table 2 and additional socio-demographics listed in Table 3 by the chief investigators or data managers of each study. Data were independently cleaned by two independent reviewers (JB and RS). Issues were resolved by consensus between four reviewers (JB, RS, GL and SP).

Table 1. Description of included studies

Abbreviations: ADM, antidepressant medication; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire 12 item version; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, depression subscale; iCBT (internet-based therapist delivered cognitive behavioural therapy); MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; T0 - Baseline; TAU, treatment as usual; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Table 2. Measures used across the studies of the Dep-GP IPD dataset meeting inclusion criteria for the present study

CIS-R was used in all studies n = 4864. BDI-II was used in six studies (COBALT, GENPOD, IPCRESS, MIR, PANDA and TREAD), n = 2858; PHQ-9 was used in five studies (CADET, COBALT, MIR, PANDA and REEACT) n = 2807; GHQ was used in ITAS only n = 796; and the Social Support Scale was used in six studies (COBALT, GENPOD, IPCRESS, MIR, PANDA and TREAD) n = 2858.

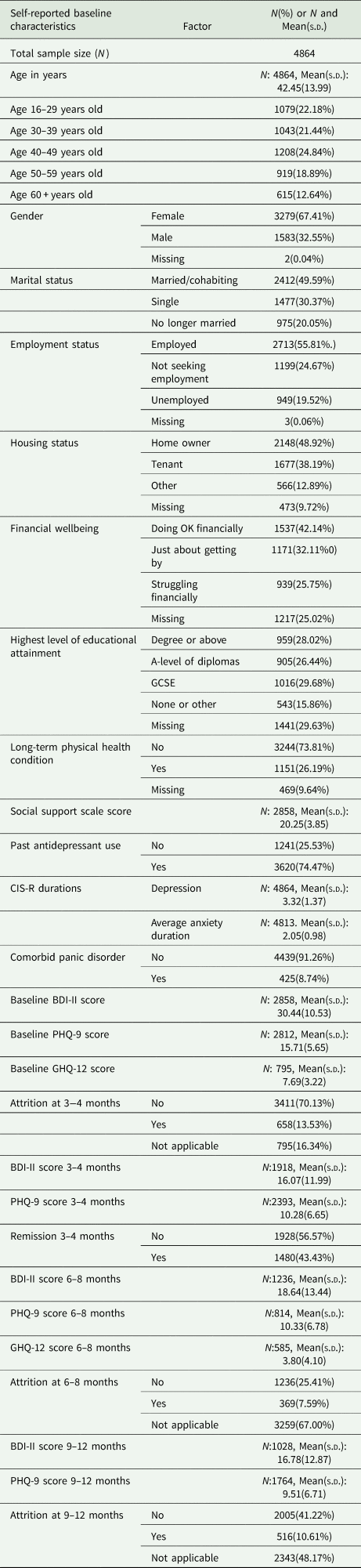

Table 3. Baseline characteristics of study sample using observed data only

Data integrity checks

Integrity of all baseline and endpoint data for each study was checked with the study team and against publications from each study. We removed two participants from IPCRESS and one from PANDA due to them missing data on over 75% of baseline variables. There were also data available on 36 more participants in ITAS than reported in the publication about that study.

Ethical considerations

All studies were granted NHS Research ethical approvals and all participants gave informed consent, see online Supplementary Table 2. No additional ethical approval was required for this study: HRA reference 712/86/32/81.

Measures

See Table 2 for details.

Data analysis plan

The pre-registered analysis plan (https://osf.io/e5zup/) is outlined below. It builds on the plan outlined in our general protocol (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, White, Lewis and Pilling2020).

Primary outcomes

Depressive symptoms at 3–4 months post-baseline were captured in two ways. (1) z-score (standardised mean) of the scores on the depressive symptom measures (BDI-II and PHQ-9) used at 3–4 months post-baseline within each study (see Table 1). The score at 3–4 months was divided by the standard deviation for that measure calculated at 3–4 months. (2) The logarithm of depression scale scores irrespective of the measure used. Exponentiation of the regression coefficient provides an estimate of the percentage difference in symptoms.

It was expected that these methods would give similar results but the log outcome might have greater utility as percentage differences are more easily understood and do not require division by standard deviation estimates.

Secondary outcomes

1) Remission on the primary depression measure in each study at 3–4 months post-baseline (a score of <10 on the BDI-II or PHQ-9, whichever was the primary measure collected at that time point in each study).

2) Depressive symptoms at 6–8 months post-baseline, as above but also including the GHQ-12, captured with (i) the z-score calculated using the mean and standard deviation for the scores at 3–4 months and (ii) the logarithm of scores at 6–8 months.

3) Depressive symptoms at 9–12 months post-baseline, as above, captured with (i) the z-score calculated using the mean and standard deviation for the scores at 3–4 months and (ii) the logarithm of scores at 9–12 months.

Prognostic indicators under consideration

1) Age was considered both as a continuous variable per 5-year increase, and in age groups: (i) 16–29 (ii) 30–39; (ii) 40–49; (iii) 50–59; (iv) ⩾60 years old.

2) Gender was taken from a question asking participants for their self-reported gender at baseline, in all included studies response options were binary. This was commonplace in studies at the time, it does not capture the appropriate range of gender identities, neither does it capture differences between gender and sex assigned at birth.

3) Marital status was initially recorded in five categories: (1) married or cohabiting (living with partner); (2) single (never married), (3) separated, (4) divorced, (5) widowed. However, some of the studies had very few participants that were divorced (n = 0 in ITAS) and widowed (n = 4 in GENPOD, n = 1 in IPCRESS and n = 6 in TREAD). Therefore, marital status was recoded into three categories to meet power requirements by combining categories 3–5 above in a new category ‘no longer married’.

Confounders and covariates

Data on some potential confounders were available in all studies whereas data on others were not (i.e., systematically missing). Following our protocol, we adjusted for the following in separate models of each outcome:

1) Depressive ‘disorder characteristics’: depressive symptom severity, the duration of the current depressive episode, mean duration of anxiety problems, comorbid panic disorder and a history of antidepressant treatment.

2) Age, gender and marital status (excluding whichever of these was already included in the model as the potential prognostic factor).

3) Employment status.

In sensitivity analyses we then added each of the systematically missing variables one at a time:

1) Housing status (available in eight studies).

2) Long-term physical health condition status (yes/no; available in eight studies).

3) Highest level of educational attainment (available in seven studies).

4) Financial wellbeing (available in six studies).

5) Social support (available in six studies).

In addition, all models were adjusted for treatment allocation by assigning each of the randomised groups across the studies a different category in a single categorical variable and including this variable in all models. This meant that associations between the prognostic factors and outcomes could be investigated having adjusted for the effects of the randomised treatments. It also meant that all models accounted for clustering effects at the study-level.

Data handling and data management

Details of the pre-processing stages and handling of missing data are given in the original protocol (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, White, Lewis and Pilling2020). Multiple imputation with chained equations was used with baseline and outcome variables to generate 50 imputed datasets for each study. Systematically missing variables were not imputed.

Primary analyses

Two-stage DerSimonian and Laird random effects meta-analyses were conducted for each prognostic factor (each fitted into separate models) for each outcome variable listed above, using the ‘admetan’ package (Fisher, Reference Fisher2015) in Stata 16 (StataCorp, 2019). Linear models were fitted for the z-score and log outcomes and logistic models were fitted for remission. The degree of heterogeneity was assessed using prediction intervals and its impact assessed using the I 2 statistic (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman2003).

Risk of bias

Two reviewers (JB & RS) conducted independent risk of bias assessments using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) (Hayden et al., Reference Hayden, Van Der Windt, Cartwright, Côté and Bombardier2013) and the quality of evidence for each prognostic indicator was assessed using the GRADE framework (Guyatt et al., Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter, Alonso-Coello and Schünemann2008). Disagreements were resolved by consensus with two additional reviewers (GL and SP).

Sensitivity analyses

In addition to those listed above sensitivity analyses were conducted if there was considerable heterogeneity (Higgins and Green, Reference Higgins, Green, Higgins and Geen2011) either from inspection of the forest plots or if I 2 was 75% or above, or if either study quality was low or risk of bias was high, removing the study contributing most to the heterogeneity/low quality/high risk of bias.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

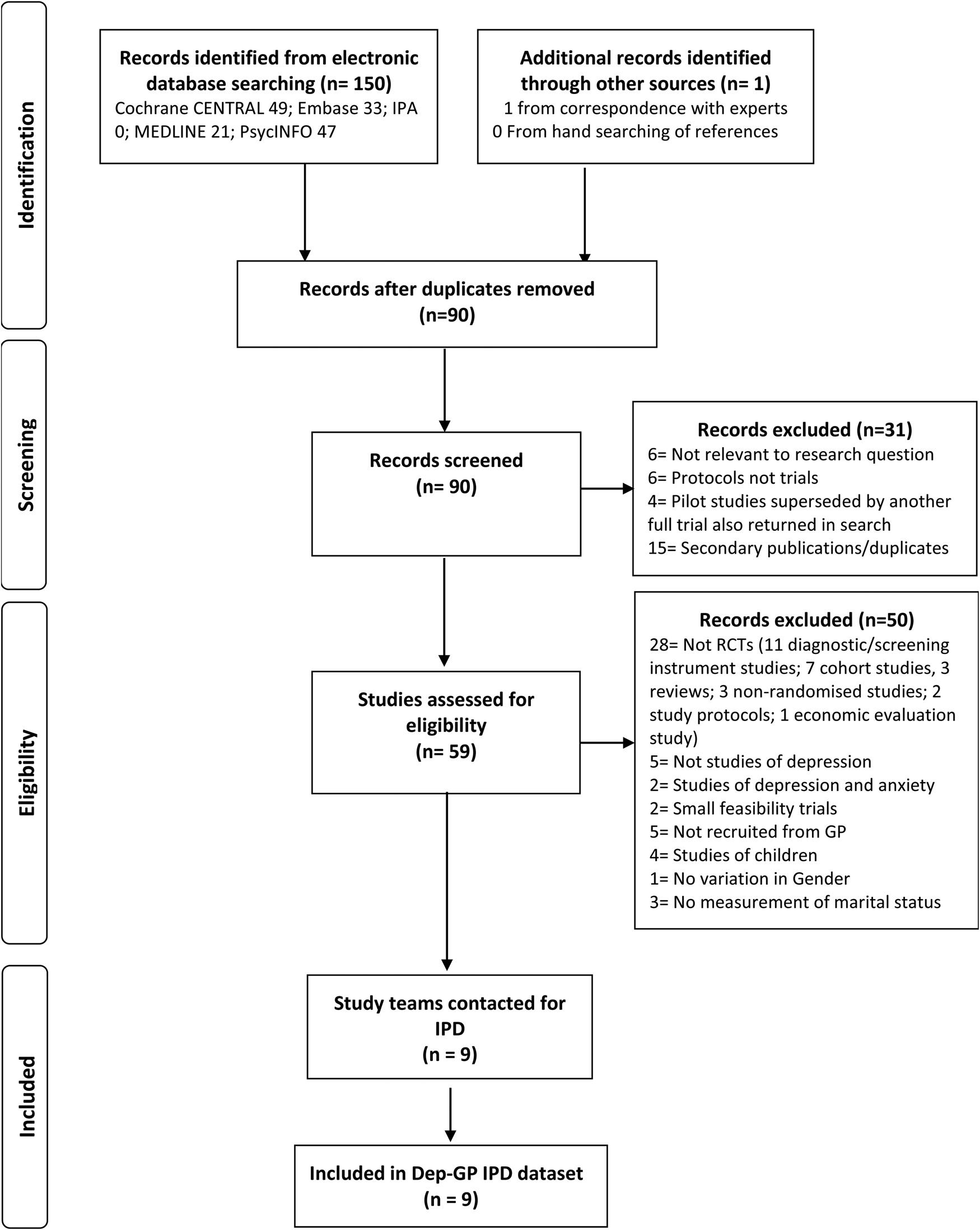

In total nine RCTs met the inclusion criteria. IPD from all 4864 participants formed the present dataset, see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow of studies through selection process for IPD meta-analysis.

Quality assessments and risk of bias

Overall, the risk of bias was low, and quality was high in all studies, so no sensitivity analyses were required in relation to these, although half of the studies had a moderate risk of bias related to attrition, see online Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. There was near perfect agreement between the reviewers, with interrater reliability (Cohen's Kappa) k = 0.96 for QUIPS and k = 1.00 for GRADE.

Descriptive statistics

Across all nine studies, age ranged between 16 and 84 years old at baseline with a mean age of approximately 42 years, 80% of the sample were aged between 23 and 61 years old. Approximately 67% of the participants were women, half of participants were married or cohabiting, approximately 30% were single and 20% no longer married (Table 3).

Association between age and prognosis independent of treatment

Overall, there was no evidence of an association between age and prognosis at 3–4 months post-baseline. This was the case when age was modelled as a continuous variable, an ordinal variable of age groups, comparing each age group to those aged 16–29 years old (see Table 4), and with age modelled with a quadratic term (p = 0.233). There was also no evidence of an association between age and prognosis at 6–8 months (online Supplementary Tables 7 and 8) or 9–12 months (online Supplementary Tables 9 and 10).

Table 4. Difference in Z-score of depressive symptoms (‘mean difference’) at 3–4 months post-baseline per unit increase in baseline prognostic indicator

Note: Association for ordinal variables is per category increase from first category shown below the variable down to the last (i.e. married to single, single to no longer married).‘Disorder characteristics' adjusted for are: baseline BDI-II score, average anxiety duration, depression duration, comorbid panic disorder, and history of antidepressant treatment.

Associations between gender and prognosis independent of treatment

There was no evidence for a difference in prognosis between men and women at 3–4 months (Tables 4 and 5) or 9–12 months (online Supplementary Tables 9 and 10) post-baseline, but there was evidence that men had worse prognoses at 6–8 months (percentage difference in depressive symptoms for men compared to women: 15.08% (95% CI: 4.82 to 26.35), see online Supplementary Table 8). However, this was attenuated when adjusting for socio-demographic factors: age, marital status and employment, 12.23% (−1.69 to 28.12).

Table 5. Percentage difference (‘% difference’) in depressive symptom scale scores at 3–4 months post-baseline per unit increase in baseline prognostic indicator

Note: Association for ordinal variables is per category increase from first category shown below the variable down to the last (i.e. married to single, single to no longer married). ‘Disorder characteristics' adjusted for are: baseline BDI-II score, average anxiety duration, depression duration, comorbid panic disorder and history of antidepressant treatment

Associations between marital status and prognosis independent of treatment

There was some evidence of an association between marital status and prognosis at 3–4 months (Tables 4 and 5). Participants who were single (difference in mean depressive symptom score at 3–4 months (0.22(95% CI: 0.15 to 0.30)) and those who were no longer married (0.28(95% CI: 0.20 to 0.37)), had more depressive symptoms at 3–4 months post-baseline on average, compared to married participants. After adjusting for the ‘disorder characteristics’ and socio-demographic factors there was still evidence that single or no longer married participants had worse prognoses than those that were married, but the strength of the associations was somewhat attenuated (see Tables 4 and 5). There were similar effects at 6–8 months post-baseline although confidence intervals included zero when controlling for employment status in addition to all other confounders with the log outcome (online Supplementary Tables 7 and 8). Further, when comparing just those participants who reported being single to those who reported being married, there was a lack of evidence for an association with prognosis at 6–8 months post-baseline after adjusting for depressive ‘disorder characteristics’. At 9–12 months there was no evidence for an association between marital status and prognosis after adjusting for the depressive ‘disorder characteristics’ (online Supplementary Tables 9 and 10).

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses including systematically missing confounding factors did not substantively change our conclusions (see online Supplementary tables 12–18), nor did analyses that removed studies due to high levels of heterogeneity (online Supplementary Table 19).

Discussion

This study investigated the associations between age, gender and marital status, with the prognosis of depression for adults that sought treatment in primary care, regardless of the type of treatment they were given. We found no evidence for an association between age and prognosis at 3–4, 6–8 or 9–12 months post-baseline and no evidence that gender was associated with prognosis after adjusting for clinical prognostic factors and employment status. There was evidence that single, and either separated, divorced or widowed patients (those no longer married) had worse prognoses than married patients at 3–4 months. However, the effect was weaker after adjusting for clinical prognostic factors and employment status.

Our recent review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses found inconsistent and at times contradictory findings regarding the associations between age, gender, marital status and prognosis for depressed patients (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021). Our findings suggest that the pattern of associations found in those past reviews may have been due to chance, or the specific features of each review. With greater power to detect effects due to having a large IPD sample here, and additional robustness by adjusting for a range of treatments and for important clinical and demographic prognostic factors, we found no overall association between either age or gender and prognosis. Although we found the that men appeared to have worse prognoses than women at 6–8 months this was attributable to a single large study that contributed data at the 6–8 months endpoint and not at 3–4 or 9–12 months, and the association was minimal after adjusting for clinical and demographic covariates. There had been limited evidence for an association between marital status and prognosis in prior reviews, here we did find evidence of such an association in our data (married patients did better with treatment). On the basis of our findings here it is unlikely that knowledge of patients' self-reported marital statuses will inform clinically meaningful differences in prognosis alone, particularly after accounting for depressive ‘disorder characteristics’ and employment status (Button et al., Reference Button, Kounali, Thomas, Wiles, Peters, Welton, Ades and Lewis2015). However, it may be important to consider in conjunction with those other factors. The strength of the association with prognosis likely lies somewhere between the prognostic effects found for a history of antidepressant medication and comorbid panic disorder (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Saunders, Cohen, Barnett, Clarke, Ambler, DeRubeis, Gilbody, Hollon, Kendrick, Watkins, Wiles, Kessler, Richards, Sharp, Brabyn, Littlewood, Salisbury, White, Lewis and Pilling2021).

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a large individual patient dataset formed from a number of RCTs to consider the prognostic status of age, gender, and marital status across different types of treatment, bringing greater precision to estimates of these associations than in past studies. In contrast to past reviews, we selected studies that included treatment seeking adults with depression recruited in primary care settings, as this is a very common route into treatment (McManus et al., Reference McManus, Bebbington, Jenkins and Brugha2016; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Chatterji, Evans-Lacko, Gruber, Sampson, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Al-Hamzawi, Alonso, Andrade, Borges, Bruffaerts, Bunting, De Almeida, Florescu, De Girolamo, Gureje, Haro, He, Hinkov, Karam, Kawakami, Lee, Navarro-Mateu, Piazza, Posada-Villa, De Galvis and Kessler2017). This may have limited the number of studies found to meet inclusion criteria for this review, but has the advantage of ensuring there is a minimum population for whom our findings may be generalisable. Further, as many of the randomised treatments here are commonly used in other settings, our findings may be informative for clinicians assessing depressed patients in other settings where there are multiple treatment options.

In addition, our inclusion criteria specified such that all studies used the same measure to determine diagnosis, assess baseline symptoms and the depressive ‘disorder characteristics’ confounders, minimising bias in harmonising the data across studies. This reduced the potential pool of studies that might have been included here. However, as IPD data were available for all studies that met these criteria we did not introduce a common source of selection bias that can occur when only a subset of trials provide IPD. It is noteworthy that from our preliminary searches only two other studies (Hegerl et al., Reference Hegerl, Hautzinger, Mergl, Kohnen, Schütze, Scheunemann, Allgaier, Coyne and Henkel2010; Perroud et al., Reference Perroud, Uher, Ng, Guipponi, Hauser, Henigsberg, Maier, Mors, Gennarelli, Rietschel, Souery, Dernovsek, Stamp, Lathrop, Farmer, Breen, Aitchison, Lewis, Craig and McGuffin2012) (totalling n = 612 patients) might potentially have met all other inclusion criteria and used other comprehensive measures of depressive and anxiety symptoms and disorders at baseline. An alternative approach might have been taken by not specifying which measure was used at baseline but instead only specifying that all of the ‘disorder characteristics’ noted to be associated with prognosis in our previous study should have been assessed. It is noteworthy though that many studies that were excluded contained no comprehensive measure of anxiety disorder symptoms or diagnoses and so most would not have assessed for panic disorder, thus would have failed to meet inclusion criteria in this way too.

We used robust methods whereby data were extracted, cleaned and checked by multiple reviewers (Buscemi et al., Reference Buscemi, Hartling, Vandermeer, Tjosvold and Klassen2006), but only a one reviewer screened the initial titles and abstracts of the studies returned in the searches which may have introduced additional bias. Although adjustments were made for a number of potential confounders, including clinical, demographic and socio-economic variables, we cannot rule out residual confounding. Further, it is possible that adjusting for baseline depressive severity may have led to underestimating the effects of marital status on prognosis, as higher levels of baseline severity might be associated with a greater likelihood of separation, divorce or of being single. In addition, using a standardised outcome is a method that has been criticised but the results using the z-score outcome were similar to those with the log outcome and the secondary and sensitivity outcomes, suggesting the use of the standardised outcome metric did not unduly affect the results. The included studies were conducted at such a time when only two categories of gender were routinely assessed and did not give participants the option to identify with non-binary gender identities. Two participants had no gender data recorded; it is not clear whether they would have chosen another gender identity were other categories available to them.

Implications and conclusions

Clinicians and researchers will continue to routinely assess for age and gender however the value of including information on these factors when considering prognosis is likely to be very limited. On the basis of these findings we might conclude that although age and gender are important for the incidence and prevalence of depression (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005), they appear to not be important for prognosis with treatment. Patients that are married appear to have better prognoses than patients that are single or no longer married. On its own, marital status is unlikely to inform a clinically important difference in prognosis after accounting for the severity of depressive illness, captured by the depressive ‘disorder characteristics’. However, as the magnitude of effects was similar to those of a number of other clinical prognostic factors, it may be equally important to assess for marital status in clinic and to include it in predictive models of prognosis. We were unable to investigate why married people have better prognoses. It is noteworthy that when adjusting for housing status, financial wellbeing and social support (in sensitivity analyses) the associations were weaker, so married patients might differ from those that are not married in these social domain, and these in turn may be associated with prognosis.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000342

Data availability

Requests for sharing of the IPD used in this study can be made to the corresponding author, any sharing of data will be subject to obtaining appropriate agreements from the chief investigators or data custodians for each individual trial dataset used here.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Ian R. White for his contribution to determining the methods for this study and writing the protocol paper that this study followed.

Authors contributions

JB, GL and SP conceived of the original project, all three along with SDH, RJD, SG, TK, EW and GA applied for and received funding to support this work. All nine of the above, RS and ZDC, wrote the initial protocol document and plan for the current study. JB and RS co-reviewed the studies with consultation from GL and SP. ZDC, NW, DK, GA and GL provided data and liaison to resolve issues and discrepancies between received datasets and publications about those studies. JB, RS, GL and SP were responsible for the screening of studies, data extraction, additional data cleaning. JB was responsible for the data analysis with support from GA, GL, CO'D, L-LA, JS and RS in particular, and consultation from all other authors. JB wrote the original manuscript with support from RS, L-LA, JS, CO'D, GA, TE, MD, SDH, SB, EL, ZDC, GL and SP. All authors contributed to consecutive drafts and approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting criteria have been omitted.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust through a Clinical Research Fellowship to JB (201292/Z/16/Z), MQ Foundation (for ZC: MQDS16/72), the Higher Education Funding Council for England (RS, L-LA, C'OD and SP), the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre (RS, L-LA and SP), University College London (GA, GL), Vanderbilt University (SDH), University of Southampton (TK), University of Exeter (EW) and University of York (SG). NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol (NW: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care). Alzheimer's Society (grant code: 457 (AS-PG-18-013) for JS). National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London (TE and MD: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health).

The studies that IPD for this study were funded by:

1. CADET: UK Medical Research Council (MRC; reference G0701013), managed by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) on behalf of the MRC-NIHR partnership

2. COBALT: This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme (project number 06/404/02).

3. GENPOD: Medical Research Council and supported by the Mental Health Research Network.

4. IPCRESS: BUPA Foundation

5. ITAS: Primary Secondary Care Interface initiative of the United Kingdom National Health Service Research and Development Programme (PSI 2-58).

6. MIR: National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (project 11/129/76) and supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol

7. PANDA: NIHR Programme Grant for Applied Research (RP-PG-0610-10048).

8. REEACT: UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (project 06/43/05).

9. TREAD: National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme.

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf. Declaration of Interest: None.