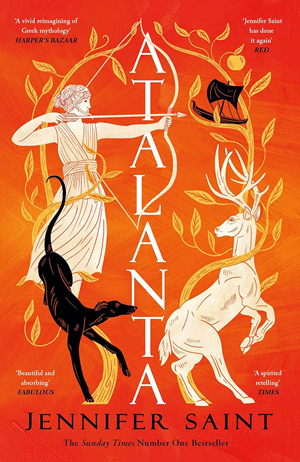

Modern retellings, in particular feminist retellings, of ancient Greek and Roman myth constitute a growing literary field, with new novels published at a rapid rate as women seek to reclaim ancient women's voices by (re)telling their stories through modern lenses. The women of the Trojan cycle are popular subjects as is Medea, with four new Medeas to be published in 2024 alone (authors: R. Hewlett, B. Le Callet, E. Quin, and J.J. Taylor). Saint's and Shepperson's additions to the field are especially welcome for their take on two less common characters. Saint takes a first-person narrator approach to tell the story of Atalanta from her exposure at birth and friendship with Artemis to her transformation into a lion, with the bulk of the novel retelling her involvement as the only woman on the Argonauts’ epic quest to reclaim the golden fleece. Shepperson, in her debut novel, rewrites the story of Phaedra, changing the original narrative from Phaedra's false rape accusation against Hippolytus to her real rape by Hippolytus, the subsequent trial, and its repercussions. These modern retellings are valuable not only for offering new perspectives on ancient women, but also as a gateway for students into the field of Classics. Younger students who find their interest sparked by modern novels are likely to seek out the original stories when they arrive at college or university and such a conduit for new students can help combat enrolments in Classics that are dwindling at most colleges and universities. That said, teachers looking to set Phaedra as a class text should be aware that there is a violent but non-explicit rape scene which can be triggering, as can the victim-blaming inherent to the narrative in general and the trial in particular. There is also a general sub-theme of the rape and abuse of enslaved women by more powerful men.

Atalanta and Phaedra, taking as their subject engaging stories about interesting characters, will appeal to a younger modern audience. Atalanta is a strong, independent woman making her own way through a hostile patriarchal world, while the comparatively passive Phaedra nonetheless courageously stands up for herself following her rape by Hippolytus; Phaedra's story is enhanced by her encounters with Medea, and there is just enough ominous foreboding surrounding the fates of Ariadne, Phaedra's sister and Theseus’ first (Cretan) wife, and the children of Medea to keep up some suspense. Unfortunately, for an older audience, especially an audience of Classicists, these novels will likely be less successful. The bulk of Atalanta retells the story of the Argonauts, with Atalanta a (disapproving) observer of the heroes’ deeds and misdeeds. The novel is very much plot-driven rather than character-driven and as such has little nuance or subtlety in character or novelty in action; it is also very heavy-handed in its disapproval of traditional ancient Greek patriarchal, hero-centric culture (Jason, epic hero and leader of the Argonauts, in particular comes across as an ineffectual cypher). Atalanta's role in the Calydonian boar hunt and its aftermath and the footrace that determined her husband, and fate, is much less detailed and seems rushed compared to the Argonautic section.

Shepperson's Phaedra also uses a first-person narrator approach but mitigates the limitations of this approach by having different point-of-view characters for each chapter; these shifting point-of-view narrators allow us to experience more than would be possible with just one narrator and so provide a more fleshed-out narrative. Some of these voices are more effective than others. The Cretan bull-jumper's chapter was well told, and the use of the older, experienced Medea, hiding in Athens following the death of her children, provided a useful counterbalance to the naive Phaedra. The individual narrators are mingled with the Night Chorus, the nameless voices of faceless slave women, lamenting their nightly sufferings at the hands of the men of Theseus’ court.

The use of the Phaedra myth to explore rape culture and the perils of a rape trial for the victim was an interesting and topical choice. Shepperson, however, is very heavy-handed in her approach, and when the heroes and villains are clear from the start – Theseus is a murderer, Hippolytus a rapist, and the innocent Phaedra easy prey for both – and the outcome inevitable, there's no real opportunity for the readers to become invested in the characters or the narrative, especially when the same note is sounded repeatedly and at length.

Phaedra includes plot elements that are not sufficiently integrated or explained. Rumours surrounding Pasiphae and the birth of the Minotaur cast a shadow over Phaedra's early years in Crete but are never explored; is this meant to foreshadow the rumours about Phaedra's chastity that plague her upon her arrival in Athens? The Minotaur is portrayed as the beloved brother of Ariadne and Phaedra and the question as to why Ariadne helped Theseus kill him is never answered, nor is the vexing question as to why the powerful Minos allowed Theseus to marry his only remaining child, when Theseus had already killed his other two, or even why the villainous Theseus wanted to marry Ariadne, and later Phaedra, in the first place (Theseus largely functions as a plot device to allow Phaedra to meet Hippolytus).

Phaedra opens with the character of The Bard, about to tell the tale of Theseus and the Minotaur. As he begins to sing, an audience member objects ‘We know this one already, foreigner. Why should we want to hear it again, and from you?’ A similar objection might be raised about modern authors retelling ancient stories, but both Phaedra and Atalanta provide a compelling answer: by updating old stories for new audiences, authors can explore issues of cultural and social relevance. The Bard then begins to sing the story of Phaedra's trial; as the Bard sings, he notices the disapproval of the women in his audience, ‘but he didn't care. He didn't sing for women. They couldn't pay for his songs.’ Both Phaedra and Atalanta (re)tell their stories for that female audience and are mostly successful: they are are entertaining, sometimes thought-provoking, and give fresh voice to female characters commonly heard only through male voices.