In recent years, new scientific applications have enabled an appreciation of the origins of rock art on different continents, adding to our understanding of its development (Hayward et al. Reference Hayward, Atkinson, Cinquino, Richard, Keagan, Hofman and Rodríguez2013; Ochoa et al. Reference Ochoa, García-Diez, Domingo and Martins2020; Podestá and Strecker Reference Podestá and Strecker2014; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2017; Samson et al. Reference Samson, Wrapso, Cartwright, Sahy, Stacey and Cooper2017). Despite constraints arising from sample types and their relationship to the graphic process, poor preservation, the amount of sample needed, contamination, potential pitfalls in pretreatment protocols, and contradictory data results (Alcolea and Balbín-Behrmann, Reference Alcolea and Balbín-Behrmann2007; Bonneau et al. Reference Bonneau, Staft, Highman, Brock, Pearce and Mitchell2017; David et al. Reference David, Delannoy, Petchey, Gunn, Huntley, Veth and Genuite2019; Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Ramsey, van Klinken, Pettitt, Nielsen-Marsh, Etchegoyen, Fernandez Niello, Boschin and Llamazares1998; Pike et al. Reference Pike, Hoffmann, Pettitt, García-Diez and Zilhao2017; Valladas et al. Reference Valladas, Tisnerat-Laborde, Kaltnecker, Cachier, Arnold and Clottes2006), the different analytic techniques used and the results obtained have yielded insights on the origin and development of each prehistoric art tradition, posing new questions and sometimes challenging previous assumptions.

The application of AMS 14C dating can determine the age of organic pigments and support an enhanced understanding of rock art, including when and how this form of graphic communication developed and when and why morpho-stylistic changes occurred; it thus enables rock art to be connected to territory and other forms of evidence from archaeological or climate studies. Rock art in the Caribbean, and particularly in the Dominican Republic, has long been the subject of thematic, stylistic, and interpretive studies (Duvall Reference Duvall2007; Hayward et al. Reference Hayward, Atkinson, Cinquino, Richard, Keagan, Hofman and Rodríguez2013; López Belando Reference López Belando, Hayward, Atkinson and Cinquino2009, Reference López Belando and García Arévalo2012, Reference López Belando2018). Yet, research on the development of these visual representations has largely been based on relative or imprecise dating methods. The existence of several direct method AMS 14C dates has notably expanded our understanding of rock art chronology (Foster et al. Reference Foster, Harley McDonald, Beeker and Conard2011; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2017; Samson et al. Reference Samson, Wrapso, Cartwright, Sahy, Stacey and Cooper2017). Our study discusses the implications of an AMS 14C date obtained for a zoomorphic pictograph in Borbón Cave No. 1 in the Dominican Republic. We also address its significance with regard to other published dates from the island.

Borbón Cave No. 1

The limestone Borbón Caves are in the San Cristóbal Province in the protected area known as the Monumento Natural Reserva Antropológica Cuevas de Borbón o Pomier (Figure 1). Seventeen sites with prehistoric art have been documented in that area (López Belando et al. Reference López Belando, Jorge Broca and Guzmán2015): their thematic, technical, and stylistic diversity signifies that this is a critical rock art group for understanding the artistic and symbolic development of Caribbean culture.

Figure 1. (A) Location of Borbón Cave No. 1 and its survey, marking the position of (B) the sampled motif.

The first rock art figures were discovered by Sir Robert Schomburgk in 1849, but it was not until 1978 that a large-scale study was published (Pagán Perdomo Reference Pagán Perdomo1978). The most representative site is Borbón Cave No. 1. It contains prehispanic remains and burials corresponding to the pottery-producing populations that inhabited the island from the seventh to the sixteenth centuries (López Belando Reference López Belando2008). Recently, the archaeological deposits were removed when the cave was prepared for tourism and public access. The rock art ensemble consists of 471 pictographs and 36 petroglyphs, including zoomorphs, anthropomorphs, and anthropo-zoomorphs (López Belando Reference López Belando2008).

The representations in the cave include a high density and large variety of images that we interpret as depictions of the magic and religious rituals of the ancient inhabitants of the island, scenes of nature, and the original fauna of the ancient Hispaniola. Many of these scenes may reflect beliefs and cosmology of the Arawakan language speakers who lived on the island before the arrival of the Europeans, as documented in the book about the myths of the Taínos, Relación de las Antigüedades de los Indios by Friar Ramón Pane, written in the late fifteenth century and reissued in Reference Pane1987.

The most frequently represented animals in the cave are birds, turtles, and some terrestrial mammals, such as dogs. The birds appear alone or in groups, sometimes interacting among themselves or with semi-human (bird people) or human individuals. Based on ethnographic information, these images may be interpreted as representations of spirit helpers of the Taíno shamans (behiques). These helpers helped the shamans fly, while in a trance, to the abode of the gods to consult them and then return to earth to communicate their words to the inhabitants of the settlement. There are also scenes of sex between animals and between a bird person and a bird. A possible representation of the ethnohistorically recorded myth of Taino twins is presented through depictions of twins joined in their bodies and arms. Another frequent topic is the inhalation of cohoba, a hallucinogenic product consumed by the shamans. Astronomical bodies, like the sun and the moon, also appear.

The art represented in the Borbón caves has a specific manner of representation that appears in other caves on the island of Hispaniola, with parallels in other Caribbean islands such as Puerto Rico and Jamaica (Dubelaar et al. Reference Dubelaar, Hayward and Cinquino1999; López Belando Reference López Belando2005). It therefore constitutes an artistic school known as the Borbón School, which is characterized mainly by the following features: (1) the concentration of petroglyphs in the entrances of the caves, which stand out because of their shape or position; (2) drawings in dark areas and in places lit by sunlight; (3) use of a single color, generally black or dark gray; (4) choice of walls of a particular color or shape that makes the motifs stand out; (5) some examples of figures drawn with a sense of perspective; (6) groups in panels and some isolated motifs; (7) the general absence of superimpositions of pictographs; and (8) a large proportion of zoomorphs, especially birds (López Belando Reference López Belando2004).

AMS 14C Dating

After examining the rock art to determine which motifs were best conserved for extraction of the sample, we selected a bird image, possibly a little blue heron (Egretta caerulea; Figure 2); it is part of a panel with other motifs (López Belando Reference López Belando2018:99). Macro-visual inspection of the layer of paint determined that the charcoal had been applied directly, as a “pencil.” We did not observe any important taphonomic processes, such as washing, deposition of clay, or anthropic action.

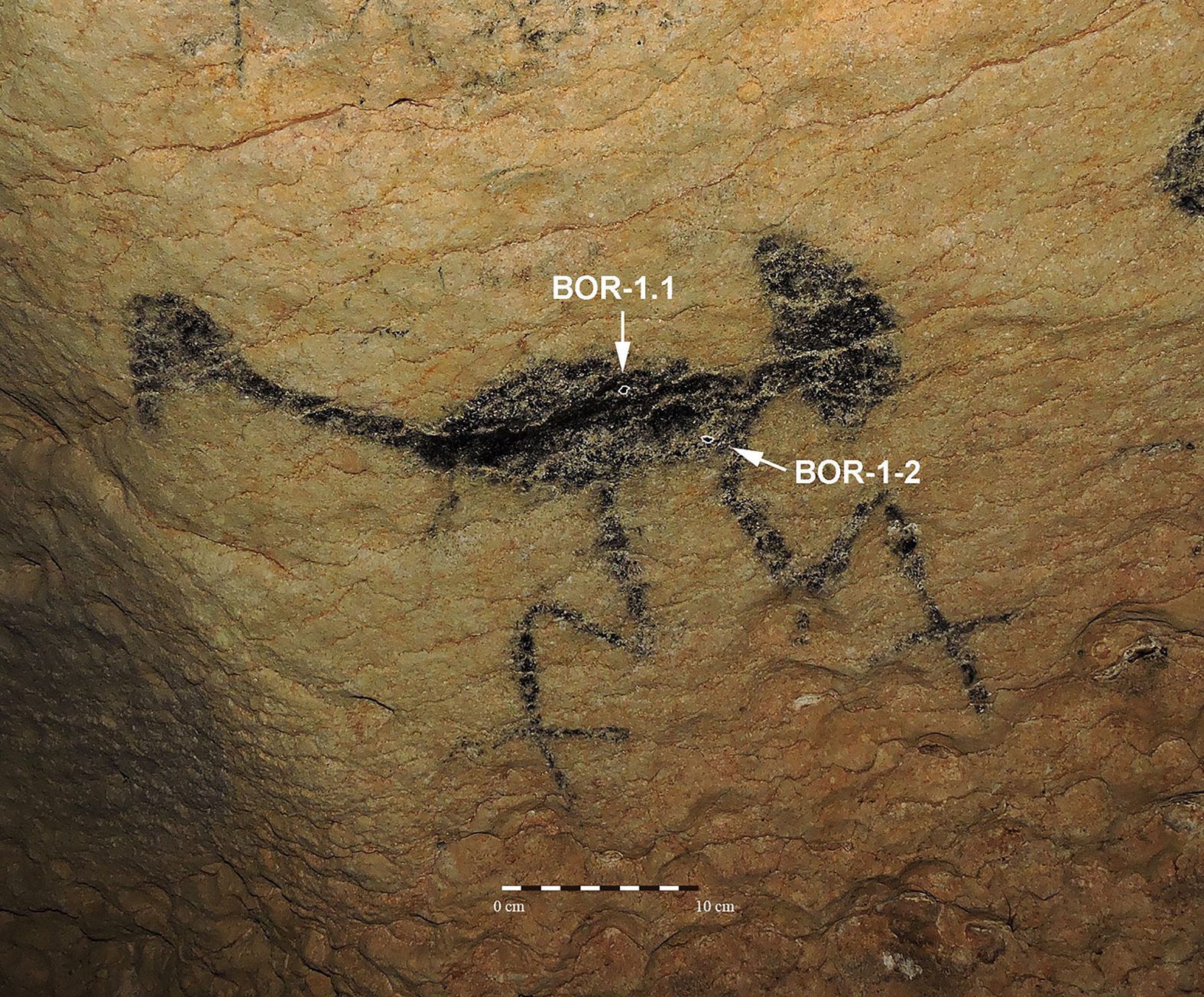

Figure 2. Bird figure dated in Borbón Cave No. 1 and the sampling points BOR-1.1 and BOR-1.2. (Photograph courtesy of the authors.) (Color online)

The sample used for dating came from two points on the image shown in Figure 2: BOR-1.1 in the uppermost part of the body and BOR-1.2 from the lower posterior part, near the start of the limb. The samples were collected with a sterilized blade and stored in a sterilized plastic tube. They were observed with an Olympus optical microscope using reflected light at 10–50× and analyzed by Raman spectroscopy (Thermo Fisher DRX confocal Raman with 532 nm excitation laser, 20 exposures for 5 sec, laser power 1mW, and 50 μm pinhole) at the Spanish Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (Sarró and Barros Reference Sarró and Barros2013). The results of the Raman analysis confirmed that the samples are of a carbonaceous substance, because the spectrum identified wide peaks in the D and G bands (Figure 3). Observation with the optical microscope confirmed that the cellular structure corresponds to charcoal (Figure 4), although the small size of the samples precluded any further identification.

Figure 3. Spectrum of the sample BOR-1.1 obtained by Raman spectroscopy.

Figure 4. Optical micrographs of the sample BOR-1.2 where the cellular structure of wood can be recognized. (Color online)

Beta Analytic carried out the dating process using acidic-basic-acidic (ABA) pretreatment. Because of the small size and weight of the samples, there was a high likelihood that no results would be obtained if they were processed individually; therefore, we combined them. The similarity in the composition and the technical homogeneity in the execution of the figure allow us to consider the samples to be a single graphic temporal event, so their combination (BOR-1.1 + BOR-1.2; sample 568016; see Table 1) does not imply different graphic action events. The calibration of the result using IntCal20 and Oxcal 4.4 determined an interval at 95.4% probability of 1045–1223 cal AD, distributed between 1120 and 1223 cal AD at 69.6%, 1045 and 1086 cal AD at 23.1%, and 1092 and 1105 cal AD at 2.8% probability.

Table 1. Characterization of the Dated Sample.

The result comes from the dating of the purified charcoal, which represents the material of the “ancient” charcoal after the contaminants were removed. The pretreatment was carried out in the routine way using acidic-basic-acidic preparations in the complete process. The weight of the datable charcoal (0.64 mg) was greater than 0.5 mg, a borderline indicator for good accuracy. Moreover, the microscopic observation and analysis before the dating process did not identify any potential pollutants, such as bat excreta, fungi, lichen, bacteria, or the action of cave-dwelling fauna. Therefore, the sample was of optimal quality, and the result can be accepted with confidence.

Discussion

Appraisal of the archaeological significance of the result should consider the potential old wood effect (Schiffer Reference Schiffer1986) and the possible use of charcoal that did not correspond temporally with the moment of the decoration because “old charcoal” had been used. Because of the impossibility of determining the charcoal taxonomically and the lack of deep knowledge of the archaeological context spatially linked to the art, we cannot resolve these issues.

The dated sample is associated with the Borbón School graphic tradition (López Belando Reference López Belando2018). The AMS 14C result confirms that the image dates to at least ± 270 years before Christopher Columbus reached Hispaniola in the fifteenth century, when the island was inhabited only by the Indigenous population.

Similar dates for the emergence of Taíno rock art production have been obtained at other Caribbean sites. In El Puente Cave in the Dominican Republic, a schematic anthropomorph with closed arms was dated to between 1036 and 1226 cal AD (Foster et al. Reference Foster, Harley McDonald, Beeker and Conard2011). In Gemelos Cave in Puerto Rico, a solar-type anthropomorph of the Borbón School provided a date between 1045 and 1264 cal AD (Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2017; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Acosta-Colon and Pérez2021). Other motifs in Puerto Rico that might be attributed to the Borbón School provide more recent dates. In Matos Cave, three dates define a continuous interval between 1281 and 1619 cal AD, and in Cave Lucero seven dates support a long graphic continuity that began in about 1225 cal AD and persisted until the eighteenth or nineteenth century.

The long duration of the Borbón School confirms that the artistic tradition of the Taíno culture continued over several centuries and was even maintained after the Spanish arrived on the island (García Arévalo Reference García Arévalo2019). This proposal agrees with other archaeological and anthropological studies claiming that “indigenous features persist in the spiritual and material culture of the Caribbean and constitute an important part of the everyday life” (Hofman et al. Reference Corinne L., Rojas, Hung, Beaule and Douglass2020:70).

Our research has characterized rock art linked to the Taíno culture from the eleventh to the early thirteenth century. The development of systematic dating programs will enable us to better understand the origin and evolution of Caribbean rock art and how population movements and human interactions affected the cultural and artistic traditions of Indigenous groups.

Acknowledgments

The research was authorized by the Ministry of the Environment of the Government of the Dominican Republic. It results from two projects: (1) Origen y desarrollo del arte rupestre antillano: Aplicación del AMS en la República Dominica (T002020N0000044487) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Culture and Sports and (2) Datación del Arte Rupestre Prehispánico de la República Dominicana funded by the Comisión de Ciencias Sociales de la Academia de Ciencias de la República Dominicana and Guahayona Institute of Puerto Rico.

Data Availability Statement

All original data produced as part of this study are presented.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.