No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

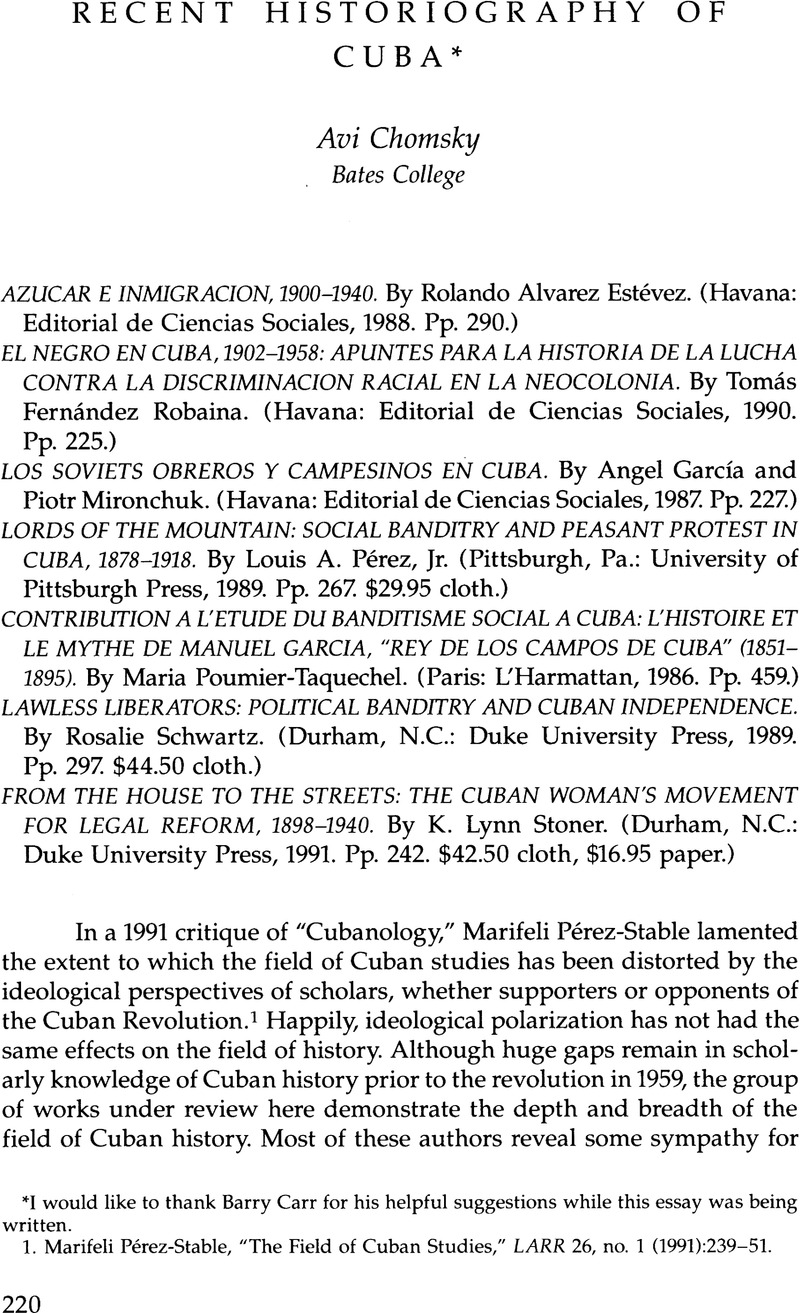

I would like to thank Barry Carr for his helpful suggestions while this essay was being written.

1. Marifeli Pérez-Stable, “The Field of Cuban Studies,” LARR 26, no. 1 (1991):239-51.

2. A notable exception to this lack of scholarly dialogue is the issue of the transition from slavery to free labor. Manuel Moreno Fraginals's El ingenio has become a classic in its English translation and has sparked extensive debate in the U.S. literature. See Fraginals, El ingenio: complejo económico-social cubano del azúcar, 3 vols. (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1978); and The Sugarmill: The Socioeconomic Complex of Sugar in Cuba, 1760-1860, translated by Cedric Belfrage (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1976).

3. The debate among Latin Americanists on banditry has burgeoned in recent years. The most direct challenge to Hobsbawm's thesis is Richard Slatta's edited collection, Bandidos: The Varieties of Latin American Banditry (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1987). Gilbert Joseph responded critically to Slatta's challenge in “On the Trail of Latin American Bandits: A Reexamination of Peasant Resistance,” LARR 25, no. 3 (1990):7-53. The debate was continued in comments by Slatta, Peter Singelmann, and Christopher Birkbeck, with a reply by Joseph in LARR 26, no. 1 (1991):145-74.

4. Pérez and Schwartz have also debated these issues directly in the American Historical Review. See Pérez, “Vagrants, Beggars, and Bandits: Social Origins of Cuban Separatism, 1878-1895,” American Historical Review 90, no. 5 (Dec. 1985):1092-1121; and the exchange of letters between Pérez and Schwartz in AHR 91, no. 3 (June 1986):786-88. A revised version of Pérez's article became the first chapter of Lords of the Mountain.

5. Part of Schwartz's antipathy toward the independence movement seems to stem from her sympathy with her main source, Camilo Polavieja, the Spanish governor general charged with doing away with banditry and separatism in Cuba. Her language often seems to reflect Polavieja's own perspective. In describing “the good intentions and dedication of Polavieja's forces” and calling them a “committed, inspired team of law enforcement officials,” Schwartz reveals a sympathy that few Cuban patriots would endorse (pp. 173, 199).

6. The translations of the citations in French are mine.

7. This work was published in 1990 by Princeton University Press.

8. For excellent discussions of how subsequent events can shape memories, see Philippe Bourgois, Ethnicity at Work: Divided Labor on a Central American Banana Plantation (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989), 52, 102-9; Jeffrey Gould, To Lead as Equals: Rural Protest and Political Consciousness in Chinandega, Nicaragua, 1912-1979 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990); and Jan Rus, “Whose Caste War? Indians, Ladinos, and the ‘Caste War’ of 1869,” in Spaniards and Indians in Southeastern Mesoamerica: Essays on the History of Ethnic Relations, edited by Murdo MacLeod and Robert Wasserstrom (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983).

9. For further comment on this subject, see Barry Carr, “Sugar and Soviets: The Mobilization of Sugar Workers in Cuba, 1933,” paper presented at the Latin American Labor History Conference, Duke University, 23-24 Apr. 1993, Durham, North Carolina. Carr's forthcoming book on Cuban sugar workers from 1920 to 1935 explores some of these issues.

10. See Verena Martínez-Alier, Marriage, Class, and Color in Nineteenth-Century Cuba (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989; originally published in 1974).

11. Thus women's participation in collective action not defined as feminist is not included. See Helen Icken Safa, “Women's Social Movements in Latin America,” Gender and Society 4, no. 3 (Sept. 1990):354-69.

12. See Deborah L. Rhode's introduction to Theoretical Perspectives on Sexual Difference, edited by Rhode (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1990).