The Care Programme Approach (CPA) was established in 1991 in England to ensure that a safety net of care was provided for people with severe mental illness.Reference Kingdon1 It set out requirements for health and social care assessment, including risk assessment, involving patients, carers, the multidisciplinary team and other agencies. It was a response to the Spokes inquiry into the death of Isobel Schwarz, a social worker whose death, it concluded, resulted from a lack of effective coordination of the care of a person who was severely mentally ill.2 Patients accepted by mental health services were required to have a key worker, a care plan and a review date. The policy described two levels, basic and enhanced. In practice, this generally meant that patients on a basic CPA were seen by a single practitioner, often a doctor in the case of out-patients, while those on an advanced plan saw a doctor, a non-medical mental health professional (later designated as a care coordinator) and, where involved, other agencies.

In 2008, the CPA was refocused on the enhanced level, although the previous requirements remained for all those under mental health services.3 The impetus for this ‘refocusing’ came from the recognition that allocation to CPA was inconsistent, and that there was a need to improve care coordination and reduce bureaucracy. A set of criteria were introduced to determine eligibility for ‘new CPA’, and principles for working with patients on CPA were described in detail.

CPA was therefore revised to describe a group of patients with more severe mental illness. Targets have been set by the government (Monitor and now NHS Improvement) for all CPA patients to have a care plan reviewed every year and, under the National Commissioning for Quality and Innovation payments framework, to receive at least an annual physical health check. The number of people on CPA is also sometimes used as a proxy for the severity of illness of individuals in services and on caseloads, and for use in service redesign.

Services have now progressed such that the broad principles of CPA are fully accepted by professionals and regulatory bodies (Fig. 1). However, there is no evidence as yet that CPA criteria are applied consistently across services, or that this has improved over the years:Reference Bindman, Beck, Glover, Thornicroft, Knapp and Leese4 current figures range from 1.7% to 23.5% of patients allocated to CPA,5 which is not proportional to morbidity. Similarly, there is no sign that the quality as opposed to quantity of care plans or health checks and interventions is adequate. The CPA definition is broad and subjective, and applying a ‘tick box’ approach to care plans and physical health checks is at best only a first step towards improving their application. Dichotomising patients into CPA or not is overly simplistic and allocation of resources has not explicitly followed, although managers probably give consideration to providing increased resources and time for increased need (whether on CPA or not). It has also contributed, despite the emphasis on its being primarily a clinical process, to an administrative rather than a person focus: ‘Care plans were described as administratively burdensome and were rarely consulted. Carers reported varying levels of involvement. Risk assessments were central to clinical concerns but were rarely discussed with service users. Service users valued therapeutic relationships with care coordinators and others, and saw these as central to recovery’.Reference Impson, Hannigan and Coffey6

Fig. 1 Care programme approach.

When it was introduced, CPA was intended to lead to a prioritisation of service delivery to people according to their needs. The allocation to enhanced CPA can be argued to have initially achieved this, and refocusing on CPA provided further reinforcement. Such prioritisation remains necessary, but allocation to CPA is a blunt instrument. In practice, applying targets to CPA and the bureaucracy that has often developed have also been disincentives to allocating patients to it.

An option to remedy this might be to seek to improve reliability of allocation to CPA by using outcome measures which profile severity, such as the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS). Symptom and/or social measures on HoNOS or Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE)Reference Whewell and Bonanno7 and risk ratings could be used in combination, for example, all patients rated as having severe mental illness (i.e. high symptom scores, or moderate with significant disability) and a medium or high risk rating according to national guidance8 for more than a month could be included. The criteria also might include consideration of a range of other issues, for example, multi-agency involvement and carer stress, but these would be more difficult to quantify reliably.

CPA and clinical pathways

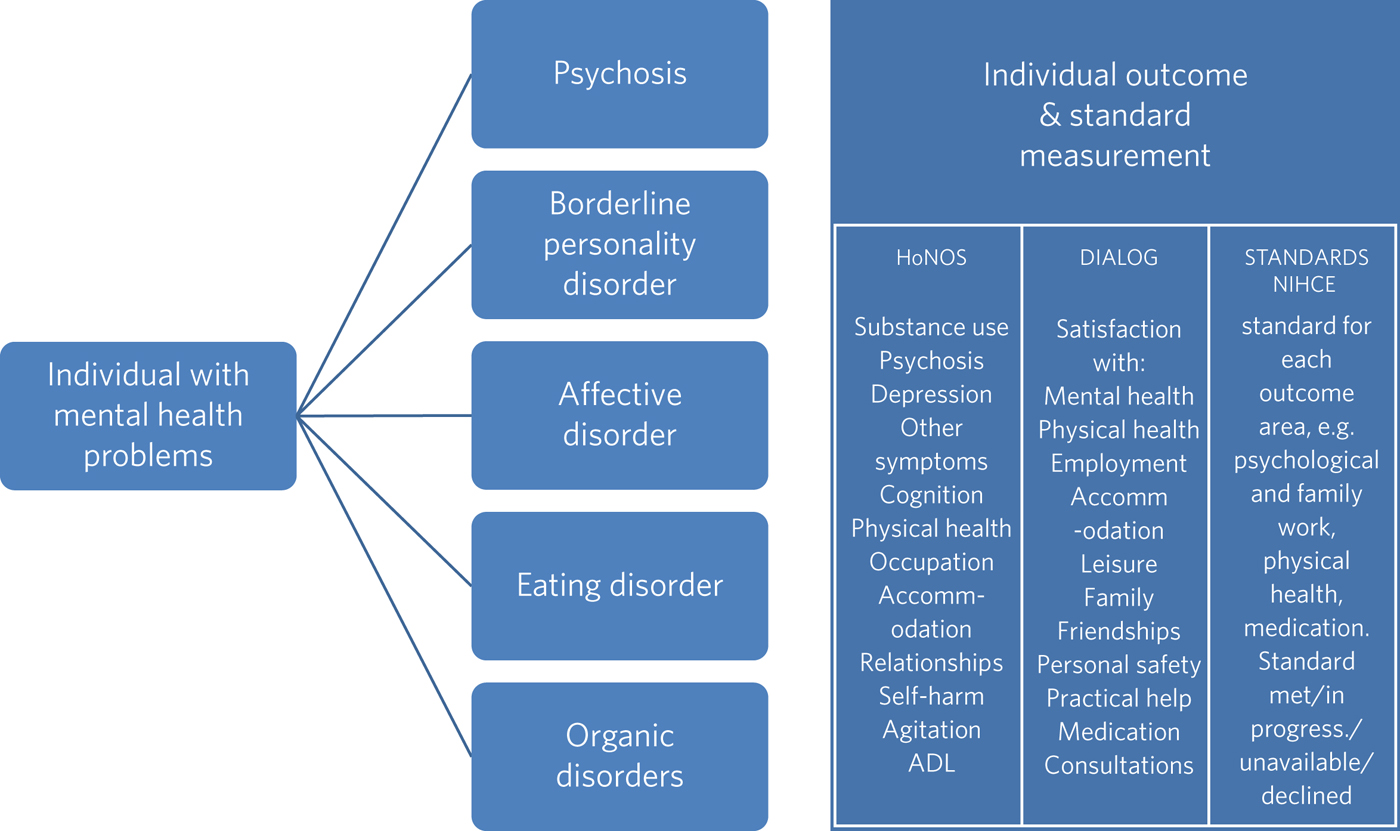

The principles of CPA have therefore been accepted as an essential foundation on which improvement of the quality of community services has been based, and broad consensus has been reached that it should be applied. However, CPA may no longer be assisting in moving services towards systematic application of the evidence-based clinical guidelines and quality standards which have been developed since it was instigated. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has described these for a range of clinical conditions, and they have been operationalised into care pathways describing ‘what should happen when’.Reference Priebe, McCabe, Bullenkamp, Hansson, Lauber and Martinez-Leal9 This requires individuals to be allocated to care pathways in accordance with their needs, which go beyond ‘severe’ and ‘less severe’ categories. These quality standards and outcome measures are relevant to pathways and need to be systematically implemented and monitored. Clinical measures such as the HoNOS and patient-rated measures such as DIALOGReference Rathod, Garner, Griffiths, Dimitrov, Newman-Taylor and Woodfine10 support this and are relatively simple and quick to use. DIALOG asks how satisfied the person is about key issues in their lives: not just mental and physical health, but accommodation, leisure, safety and relationships. It profiles need and clinical state, provides a patient-rated experience measure and links directly to care plans by eliciting the specific issues with which the individual wants help (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Pathways, outcomes and standards.

Such outcome measurements can allow the development of definitions of recovery, meaningful improvement, stability and deterioration. These may be more complex than those used for Improving Access to Psychological Services, but, in practice, it is feasible to set service definitions using these measures and other available information, e.g. relapse or disengagement from services. Recovery or improvement can be reflected by using a balance of increased satisfaction levels, symptoms, functioning and lower needs. Quality and outcomes can be improved and payment systems developed to replace block contracts, which have been blunt and ineffective instruments to fund services and are very vulnerable to arbitrary cuts. Subdivision into costing groups will become possible as data develops with greater clinical validity and reliability than the current ‘clustering’ system.Reference Kingdon11 These costing groups can use some of the principles and practice used in ‘clustering’, but by using condition pathways and severity scores linked to clinical guidelines and quality standards.

A starting point, therefore, is allocation to pathways, e.g. psychosis, affective, emotionally unstable personality and organic mental disorders, using broad NICE clinical guidelines which can be expanded to the further pathways, e.g. within affective disorders, bipolar, depressive and individual anxiety disorders, as these are embedded in services and reach across the lifespan. Although patients may have multiple conditions, primary pathways can usually be allocated in practice. HoNOS and other measures can then be used to determine symptom severity to provide groupings and weightings for physical health issues, and social needs can be incorporated. Use of pathways and severity can lead to more meaningful prioritisation than attempting to allocate to CPA or non-CPA across all patients with mental illness. Prioritising within each pathway in terms of need and risk is more meaningful for measuring whether standards are being met and directing evidence-based care.

Our experience with replacing clustering with allocation of pathways, DIALOG, HoNOS and standards assessment with an algorithm for severity/pathway ‘clusters’ has been positive, with ready acceptance by mental health staff (over 5000 allocations made within the first 3 months). This algorithm is now providing clinically relevant data to redesign, support and manage services, and is being developed with local clinical commissioning groups for costing purposes.

Do we need CPA?

So do we need to retain CPA? ‘Allocation to CPA’ is currently a means of defining a level of severity, but allocation to clinical pathways and use of outcome data to profile groups is a much richer and more reliable approach to identifying and quantifying need. Clinical practice is not dependent on whether someone is on CPA or not, but is an individualised process. CPA has been invaluable in setting principles and practice to follow as services in the community have developed, but mental health services now need to move beyond it. CPA might possibly have a role in differentiating those with greater risk and need from those with less risk, but is this really helpful in clinical practice, service design and benchmarking?

Why should NHS Improvement, as currently, expect 12-month reviews of care plans only for people on CPA? Isn't this relevant to all people in mental health services, although the complexity and length of a care plan will vary according to the needs addressed? Is the physical healthcare of people on CPA, another target, more important than that of those who are not? There is certainly an issue of prioritising resources to ensure the most effective care, but isn't a person who is not on CPA with diabetes at least as in need of linking with primary care as one who is on CPA but lacks a physical health problem? CPA has done an invaluable job, but time has passed and more individualised and sophisticated pathway-based systems should now be adopted.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the Southern Health NHS FT/Hampshire CCG CPA and care planning group and the UK Routine Clinical Outcome Measures group, whose comments have contributed to this article.

About the author

David Kingdon is a professor of Mental Health Care Delivery at the University of Southampton, and Clinical Director (Adult Mental Health) and honorary consultant psychiatrist to Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust. Rehabilitation services in Hackney, London, led by John Reed (then senior psychiatrist in the Department of Health), and in Bassetlaw, Nottinghamshire where David Kingdon was clinical director, were the inspiration for the CPA policy after the professional bodies at that time had been unable to agree a way forward. After moving to work in the Department in 1991, dissemination of CPA was a key part of the role as a senior medical officer. David Kingdon's interest in the CPA process and development has continued since appointment as a professor of mental health service delivery and through involvement in many policy, research and management initiatives, and in developing and implementing evidence-based practice for severe mental illness.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.