1. Introduction

Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of civilization, and he will grow to possess a civilized language and habit…. The school at Carlisle is an attempt on the part of the government to do this. Carlisle has always planted treason to the tribe and loyalty to the nation at large. Footnote 1

—Captain Richard C. Pratt, Superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 1892The advent of white civilization has forced on the Indians new problems of health and sanitation that they, unaided, can no more solve than can a few city individuals solve municipal problems. The presence of their villages in close proximity to white settlements make the health and sanitary conditions in those villages public questions of concern to the entire section. Footnote 2

—Lewis Meriam, PhD, 1928Some years ago at a Congressional hearing someone asked Alex Chasing Hawk, a council member of the Cheyenne River Sioux for thirty years, “Just what do you Indians want?” Alex replied, “A leave-us-alone law!!” Footnote 3

—Vine Deloria, Jr., 1969Captain Pratt, Dr. Meriam, and Councilman Chasing Hawk captured the enormous change in federal Indian policy in the past century and a half. The 1880s brought a nadir in Native American political power—the policies of forced assimilation that Captain Pratt exalted were firmly in place. Yet there was no inexorable march away from Pratt's White supremacy, to Meriam's pragmatic attention to material suffering, and to Chasing Hawk's expression of Native Nations’ self-determination. What factors drove the variation in federal Indian policy? More particularly: When and why did U.S. policymakers adhere to the rights of Native Nations?

To answer that question, I use quantitative and qualitative analysis of congressional hearings on federal Indian policy from 1889 to 1970. I contend that this analysis can expand our understanding of the role of race, federalism, and regionalism in American political development. The findings reflect three important trends in American political development in the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century. First, Native Americans forged select, perilous, yet effective interest-based political coalitions with non-Native rural westerners. Second, shifting congressional representation from the West altered the course of national politics. Third, policy change reflected the dynamic maneuvering for power within U.S. federalism between all three of its sovereigns—states, tribes, and the federal government.

The study of U.S. federalism must notice the three sovereigns at the heart of American government. In times when federal authority was the greater threat to the autonomy of both nascent states and imperiled tribes, Native Americans and their non-Native neighbors shared a cross-racial interest in checking federal power. State and territorial governments were hardly friends of the Indian. But sometimes the federal threat dwarfed the threat that states and tribes posed to each other. The West had been shaped by extensive, robust federal intervention on and off reservations. Both western states and tribes pushed back: sometimes separately, sometimes together.

This article's gaze to western politics helps clarify the regional variation in American political development. For instance, it illustrates why it is worthwhile to notice the role of Indian Removal in the subsequent politics of the South. Indian Removal skewed southern politics—and shaped much subsequent scholarship on race and U.S. federalism—by purging the region's oldest sovereigns and transforming southern politics into a competition between two sovereigns—the states and the federal government. “On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise” with enduring consequences for its lands of destination, as the majority decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma noted.Footnote 4 May we be reminded to consider the enduring consequences for its lands of origin as well. The southern political dynamic has been changing, however, particularly over the past several decades. Among the many Native Nations that persisted in southern states but were denied federal legal status, to date twenty tribal governments have secured federal recognition of their sovereign rights.

2. Theory

2.1. The Role of Interests

First, I argue that non-Native American interests—more so than non-Native ideologies—shaped federal Indian policy when western rural political representation was at its peak. I also argue that there were shared interests in the rural West—both Native American and non-Native—in minimizing social dysfunction and severe suffering on reservations. Meriam's quote reflects an orientation that developed decades earlier among many who lived on or near reservations: a focus on efficiency, utility-maximization, and measurable social ills.

Much present-day scholarship on race in American political development pays important attention to the role of ideology in shaping political coalitions and policy outputs. I don't seek to reject the hypothesis that ideology shapes race policy. I do, however, want to examine when and how interests determine the course of race policy.

Indeed, local non-Native American interests in securing the well-being of their bodies and belongings produced an ideologically inconsistent policy agenda. When it came to addressing social dysfunction, local non-Natives often supported the (human) rights of tribal governments and members, all the while opposing the (land) rights of tribal governments and members. They threaded a curious needle in suggesting that Native peoples had a right to their human welfare and dignity, but not to the lands that were vital to survival. As an ideology, such an argument would be incoherent. As a statement of self-interest, the argument fulfilled its purpose: non-Native Americans protected their personal welfare from negative externalities and their possessions from Native land claims.

Indeed, anyone with a realistic appraisal of conditions on the ground could see that the assimilationist model of social change was deeply flawed. Social reformers argued that assimilationist policies would elevate not just the morals of Native peoples but their material conditions as well. In the assimilationist logic, once Native Americans became English-speaking farmers who followed Euro-American values, they would become self-sufficient, thriving, contributing, and integrated members of Euro-American society.

Both economic and social realities were wildly different. As for economics, federal policy had eliminated traditional Indigenous economies and had already transferred the most desirable Indigenous lands to settlers. Assimilation demanded that Native Americans become successful farmers, but the lands remaining to them were the least arable in a region where agriculture would be marginal until the arrival of massive irrigation projects later—irrigation projects often achieved with the inundation of Native lands. As for society, it was one thing for eastern reformers to imagine that assimilated Native Americans would be fully accepted as members of White communities that were thousands of miles away. For the people living in those communities, however, it would be evident that many Whites were not willing to fully embrace Native Americans as friends and neighbors.

Even more importantly, the advocates of assimilation failed to appreciate the commitment and savvy with which Native Nations would resist federal assimilation policies. Native peoples experienced immense pressure to change their values and suffered great privation when they did not comply. Yet, Native resistance was intense. Native peoples used astutely their remaining political resources to deflect government domination when they could.Footnote 5 One tactic, of many, was playing state and federal powers against each other.

In short, Pratt and other assimilationists did not succeed at forging a coalition that bridged ideology and interest. Instead, local non-Native Americans had a strong stake and pressing concern about the practical considerations that Meriam presented: negative externalities from dysfunctional reservations. With time, it became clearer that assimilation policy was not delivering its promised outcomes. All the while, rural western political power was growing.

2.2. Political History of Governing Institutions

Second, as changing political institutions caused western rural power to rise and fall, national policy shifted. From 1889 to 1970, political representation of the U.S. West was transformed. Ten new, largely rural states were admitted from 1889 to 1912. As the twentieth century unfolded, western representation was then reshaped by urbanization. These immense changes in political access provide a unique opportunity to evaluate the political role of western rural interests and Native American advocacy. They also form a foundation for study of the treacherous and complex political terrain that Native Nations traversed.

At the turn of the twentieth century, twenty new western senators arrived in Congress—after a long gap in the admission of new states. Subsequently, the urbanization of the West mid-century led to explosive growth in western representation in the House of Representatives and a shift in political power within the West from rural to urban interests. In 1903, there were thirty-eight western members in the House of Representatives. By 1963, there were eighty-three western members. I want to consider the implications of these transformations in western political representation. Western industrialization and urbanization meant that western voters, economies, and political power shifted away from the rural areas with land-based economies where reservations and their neighbors were located. Now, both western interests and information were very different.

In brief, the historical record illustrates that the foundations of assimilation policy were enacted before most people living on or near reservations had representation in Congress. As western representation grew, objections to assimilation policy entered congressional debate, leading eventually to a repudiation of assimilation policy with the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934. But later, while the West urbanized, many assimilationist objectives re-emerged in termination policy.

2.3. Hypotheses

I argue that federal Indian policy provides an especially robust test of whether interests shape policy, because of the great variation in the political power of interested actors from the late nineteenth century forward. As the territories that were most affected by antebellum federal Indian policy transformed into states, their political power expanded. Yet as the twentieth century unfolded, the regions within the West most affected by federal Indian policy saw their political power decline. Western industrialization and urbanization removed western voters, economies, and political power from the rural areas with land-based economies where reservations and their neighbors were located.

If my analysis is correct, it should have several implications that can be observed in the data. First, political outcomes should have changed as the political representation of non-Native Americans near reservations rose and fell. Specifically, as western territories become states, the political influence of non-Natives near reservations should have expanded. But as western states urbanized and non-Natives near reservations became an increasingly smaller part of their state constituencies, their political influence should have contracted. Furthermore, if my analysis is correct, then tribal governments and nearby non-Native Americans shared interests in health and welfare on reservations. On issues of land rights, however, their interests diverged. Non-Native interests were intellectually inconsistent, but consistently self-serving. Non-Native Americans could support some of Native Nations’ objectives in order to secure their own physical well-being. To secure their belongings, however, they did not support Native land rights.

More specifically, if rural non-Native and Native Americans had shared interests in Native social welfare but conflicting interests on land rights, then a number of empirical implications should bear out in the data. Patterns of western Native and non-Native American testimony should (1) parallel each other, (2) differ from patterns of federal bureaucrats and members of Congress, and (3) change when topic of hearing is land rights. Furthermore, changes in western rural representation should change access to hearings. Specifically, (4) as western states were admitted to the Union, access should have increased for Native and non-Native American witnesses, and (5) access should have declined as urbanization shifted attention away from (largely rural) reservations and the non-Native communities near reservations.

3. Existing Scholarship on Race in American Political Development

For my analysis, I draw on the insights from C. Vann Woodward's 1955 The Strange Career of Jim Crow about southern race policy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the state-specific, interest-based politics behind them.Footnote 6 Woodward's key insight was that the enactment of Jim Crow policy was driven by “practical politics” and material interests. Of course, Woodward paralleled Key's 1949 finding that Jim Crow's sustenance lay in political institutions that preserved economic privilege, and these politics took different forms in different states.Footnote 7 Jim Crow was not simply the result of a racist ideology that was reasserted by White Southerners after Reconstruction ended. Rather, Woodward contended, Jim Crow policies emerged in the 1890s and were enacted often piecemeal over decades, with different timing in different states. Southern conservative patricians pursued “permission to hate” politics to rupture a cross-racial political coalition as it emerged in local contexts.

Woodward suggested that some scholarship had mistakenly emphasized ideology as the source of Jim Crow because that scholarship examined too short a time frame. It took longer-term studies of the policy stream to understand when “the even bed gave way” and when the stream encountered “sheer drops and falls” or “narrows and rapids.”Footnote 8 Woodward's argument has implications for studies of the politics of the policy process that have tended to focus on relatively shorter time frames. Here we can draw on Sheingate's language: in a shorter time frame there is difficulty distinguishing “adjustments” from “change.”Footnote 9

More recent scholarship provides us with a further understanding of when ideologies can be manipulated to override interest and when they cannot. This literature's frameworks could explain why easterners, at far remove from reservations, pushed federal Indian policy based on ideology; but westerners on or near reservations sought policy based on their interests. Specifically, when information about interests is more easily available and more relevant to nonpolitical choices, ideological criteria will decline in importance. For example, Glaeser emphasized that hatred is a heuristic that can substitute for accurate information when the overall returns to gathering information about interests is low.Footnote 10 Yet as private benefits increase from information about targeted minorities, individuals are less likely to rely on the hate heuristic. DeCanio offered parallels targeted to the study of American political development. DeCanio invoked the ideology/interest trade-off: Many individuals used ideology to evaluate policy when their information about a policy area was low.Footnote 11 For those with more at stake and specialized information, however, self-interested behavior could emerge. The parallel to federal Indian policy would be that eastern abstractions were distant from rural western experiences. Such an outcome fits the historical scholarship, as Hoxie summarized: “Most Indian groups lived in areas that were still federal territories in the 1880s; interests that might have objected to the government's programs were unrepresented in Congress…. Indian reform allowed [eastern] whites to adopt ‘principled positions while taking few political risks.’”Footnote 12

The question of when interests and when ideology shape politics has been important to the study of American political development. Brandwein, Sheingate, and Katznelson and Lapinski reviewed the extensive debates about the role of ideologies and interests in American political development.Footnote 13 King and Smith advanced a thesis about ideologically grounded racial orders in American political development.Footnote 14 They argued that race policy has alternated between a White supremacist order and an egalitarian transformative order, which bring together both interests and beliefs. Ideologies can hold coalitions together even as specific interests change. Novkov, and Nackenoff and Novkov further considered how culture and ideas of citizenship shaped the political incorporation of marginalized groups.Footnote 15 Lieberman also examined the role of beliefs and their connection to political institutions.Footnote 16 Bruyneel, in his analysis of Native American politics, contended that ideas of political identity are important components in reframing and re-articulating racial orders.Footnote 17

I am not alone in my attention to interest-based motives in western race policy, however. Frymer documented how federal policy in the West channeled White settlement to secure White land claims and political power. For example, the transformation of Indian Territory into the State of Oklahoma—a state where the population was predominantly settlers and where tribal governments would have weaker powers than in most other states—was the result of repeated and extensive federal efforts to reshape land control in the territory.Footnote 18 Spirling found that U.S. bargaining power explains the harshness of treaties and treaty-like agreements between the U.S. and tribal governments.Footnote 19 Most notably, trends were uninterrupted by 1871 congressional action that put an end to the treaty-making process, legislation that was in line with assimilationist ideologies. In essence, strength trumped beliefs. Similarly, Estes described the material interests driving federal Indian policy: “There is one essential reason why Indigenous peoples resist, refuse, and contest US rule: land. In fact, US history is all about land and the transformation of space, fundamentally driven by territorial expansion, the elimination of Indigenous peoples, and white settlement.”Footnote 20

This argument—which, at first glance, may seem unique to western politics—has implications for the study of other regions of the country. For instance, Indian Removal distorted southern politics—and much subsequent scholarship on race and U.S. federalism—by purging the region's oldest sovereigns and transforming its federalism into a competition between two sovereigns—the states and the federal government. From the 1830s to 1850s, the federal government purged the South of the preponderance of tribes with legal federal recognition, with forced marches of recognized tribal citizens to Indian Territory. Readers should note that Indian Removal was not exclusively a southern policy: It overlapped significantly with the states that would eventually join the Confederacy, but it was not unique to those states.

Seen through Maggie Blackhawk's framework, the post-Removal dichotomy set states’ power used to trample minority rights against centralized federal power used in the service of minority rights. When legal and political analysis includes all three sovereigns, however, justice for minorities can take the form of centralized federal protection of minority rights or the decentralized minority power that tribal governments provide. While the federal government may be a more hospitable protector of minority rights, it also may be a rival to minority power. When the three sovereigns are present, the political struggles over centralized power do not coincide with struggles over minority protections.Footnote 21

Wilkins's findings complement Blackhawk's claims. Wilkins demonstrated that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the federal government was the greatest threat to Native peoples.Footnote 22 Due to the specific political powers of Native Americans as citizens of tribal governments, the legal measures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to create second-class citizenship for Native Americans were distinct from those used to the same ends against African Americans. There are important connections between Native and African American politics in this time period, of course, especially for peoples with both Native and African American identity. While Wilkins wrote that “the most fundamental similarity between the African American and Native American experiences was the lack of humanity that the white establishment presumed each group to possess,” he spotlighted massive differences in the federal policies affecting Native and African Americans.Footnote 23 The legal status of Native Nations would result in political opportunities unavailable in the South at the time.

Studies of Southern politics after Indian Removal miss the interplay of the triple sovereigns that is core to U.S. federalism. Native Nations that managed to persist in the South slowly received federal recognition—and the status in federal law that accompanies that recognition—from the 1860s up through the modern era. Through that process, we have seen political institutions in the South move closer to the design of U.S. federalism. There are now twenty federally recognized tribes spanning eight southern states, and with an upward trajectory: There are even more tribes in the region with a solid basis to push for federal recognition.

In short, this article focuses on the West but does not tell an exclusively regional story. This analysis is informed by a rich and substantial scholarship on the interplay of race, interests, and power in American political development. It builds on literatures on Native American politics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and it is relevant to debates about the political essentials for White supremacist coalitions.

4. History of Federal Indian Policy

What does the historical scholarship say about my hypotheses? I begin with an overview of federal Indian policy in the time period that I analyze, and then take a deeper dive into historians’ scholarship on events between 1887 and 1934. A detailed review reveals much more to appreciate about the politics of federal Indian policy, with important implications for understanding federal Indian policy in subsequent eras. Specifically, three key features emerge. First, the ideological coalitions undergirding federal assimilation policy were not sound. Second, interest-based coalitions were enabled by changing congressional representation. Third, these interest-based coalitions reflect core features of U.S. federalism.

4.1. A Brief History

In the 1880s, the military domination of Native Nations was largely accomplished, and federal Indian policy shifted to the objective of cultural assimilation. Under assimilation policies, Native American life was shaped by the potent combination of intense federal intrusion into daily personal affairs and the wide-scale destruction of traditional Indigenous economies.Footnote 24 Federal agents regulated religious ceremonies, marital practices, access to food and money, and the ways that adults and children spent their days. Native children were routinely forced to attend boarding schools far from home where they were not permitted to wear traditional dress or to speak Native languages, and where child abuse and disease were rampant. Felix Cohen described this era as “perhaps the greatest concentration of administrative absolutism in our governmental structure.”Footnote 25

Federal assimilation policy also upended the basic structure of reservations. With the General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act, the federal government carved up many reservations into individual homesteads, selling to non-Native American settlers the “surplus” lands that remained after homesteads were allotted. Through these allotment policies, tribal land holdings fell from 104.3 million acres to 52.7 million acres by 1933.Footnote 26 In the early years of the twentieth century, federal legislation focused on the full achievement of allotment and made “excess” and “unused” tribal lands available to settler farmers, ranchers, and miners.Footnote 27 Legislative proposals to change federal Indian policy emerged, but success was limited through the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Native American protests and congressional hearings on federal Indian policy continued. One important indicator of policy change was the Department of Interior's commissioning of the 1928 Meriam Report. The Meriam Report documented appalling conditions on reservations nationwide, presented a powerful critique of Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) policy, and laid the groundwork for the end of assimilation policy.Footnote 28 The conventional historical account of the Meriam Report and later policy changes in the 1930s emphasized the entrance of new political elites into the debates over federal Indian policy who believed in cultural relativism.Footnote 29 Change reached its height under Franklin Roosevelt. New Department of Interior leaders—and in particular, Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier—promoted the end of assimilation policy and the return of key self-governing powers to tribes. The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 restored important federally recognized self-government powers to tribal governments. The IRA had limitations, although it still provided a vital mechanism for tribes to establish governments with federally recognized control over internal affairs.Footnote 30

Yet the course of federal Indian policy would change again after World War II. The trend toward acknowledging self-determination was undermined by termination policy in the late 1940s. Under termination policy, federal assistance to reservations would end, tribal governments would be stripped of their authority, and states would assume jurisdiction over tribal lands. Termination policy blended interests and ideology, including its alignment with anti-communist beliefs. The newly ascendant termination policy resembled the once-favored assimilation policy in some ways, but not in others. In the end, both schools of thought centered on the repudiation of tribal sovereignty and of the “bonds of tribalism.”Footnote 31

The initial termination legislation applied to a subset of tribal governments, with plans to terminate many more tribal governments over time. Thus, the fight over termination was to be decided not in a single, high-profile legislative debate but in myriad bills over nearly two decades. In the face of this threat, Native American leaders renewed their efforts to shape federal policies. The decades after World War II saw a marked growth in Native American advocacy organizations. A good amount of termination legislation was stopped, but not all of it. Public Law 280 was one such legacy of termination that was never reversed; it awarded criminal jurisdiction over reservations to select states.Footnote 32

The early stages of termination policy began in the late 1940s; the policy ceased in 1970, when President Nixon officially repudiated the policy of termination and declared that the aim of federal Indian policy was Indian self-determination. Nixon proposed numerous legislative initiatives to facilitate self-determination. Partial enactment of these proposals came in 1975, with the passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act.Footnote 33

The conclusions from the historical scholarship can be summarized as follows. At the national level, assimilation policy emerged in the 1880s and dominated into the 1920s. The 1930s brought seminal policy change with the recognition of tribal self-governing powers. Yet the victories of the 1930s were attacked by termination policies of the late 1940s, ’50s, and early ’60s.

4.2. Shortcomings of Ideology

At first blush, it might appear that the Dawes Act of 1887—the hallmark legislation of the federal policy of Indian assimilation—neatly blended the beliefs of eastern, paternalistic, White supremacist social reformers with westerners’ material desires to expropriate Native American lands.Footnote 34 First appearances aside, the Dawes Act was a flawed mechanism for a coalition of both ideology and interest. Assimilation policy of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was more closely tied to belief systems than the policies that preceded it: was grounded in a moral philosophy and designed around ideology.Footnote 35 Of course, federal Indian policy has never been free of ideology, assimilation policy was never free of interest, and assimilationist aims had contributed to federal policy for a century. Historians conclude, however, that the assimilation policies that started to emerge in the 1880s were more ideological than the federal Indian policy that preceded and followed it.

Prucha noted that some western members of Congress challenged the Dawes Act in congressional hearings because they saw that assimilation simply wouldn't work; these objections continued after the bill was enacted.Footnote 36 In this context, amid horrors of absolutism unfolding on reservations, elements of assimilation policy were at play in Congress:

In particular, the period from the late 1880s to the early 1920s—an era of allotment, assimilation, and plenary power—is arguably the blackest period for tribes as they struggled to adapt to a radically changed political, demographic, and economic environment. Nevertheless, throughout even these starkest years, tribes persistently reminded the federal government of its multiple obligations, those extracted by the tribes in treaties, those the United States was legally obligated to provide, and those “voluntarily assumed” by the federal government.Footnote 37

Tribes made these arguments not only in person but also through lawyers and lobbyists in DC that they regularly employed. Tribes engaged in extensive petitioning of Congress to undermine claims of their backwardness, emphasize their sovereignty, and challenge federal injustice and oppression. As tribal advocates unmasked the U.S. government's moral failings, they spotlighted both the government's hypocrisy and its failure to achieve its stated goals. This rhetoric had the ability to undermine assimilation policy and influence Congress as it “perforated ideologies.”Footnote 38

Tribal political initiatives were rhetorical and still highly concrete. In the context of these complaints, a congressional committee conducted field hearings in Indian Territory in 1906 and 1907, where witnesses “telegraphed the message that the vanishing policy was an ultimate failure and that the moralism of the old reformers was an unsound basis for conducting Indian affairs.”Footnote 39 From 1912 to 1916, members of Congress repeatedly introduced bills to allow tribes basic powers of self-government, including the power to select OIA agents for their reservations. An intense campaign of assimilationists in the 1910s to outlaw the use of peyote in Native American religious ceremonies did not succeed.Footnote 40 In 1913 and 1917, Congress created a Joint Commission to Investigate Indian Affairs, although ultimately none of the commission's proposals were passed.Footnote 41 As a counter measure, in 1919 and 1920, the House Committee of Indian Affairs conducted an investigation with the intent to “hasten the final division and dismemberment of Indian communities.”Footnote 42 But instead, the hearings documented poverty and the failure of assimilation policy. “When they took the witness stand before these congressional committees, tribal leaders were not simply talking back to government; they were articulating issues and framing concerns that that would preoccupy their communities for decades to come. Indian leadership … was building its case.”Footnote 43

Pushback against federal Indian policy continued into the 1920s and achieved more successes.Footnote 44 As Rusco notes of the era, while attempts to change federal Indian policy nationwide struggled, geographically tailored bills had better success:

The most effective congressional lobbying by Indians was accomplished by Indian leaders and Indian or other attorneys or lobbyists speaking for Indian governments, who advocated or opposed specific bills affecting one or few reservations or Native American societies.Footnote 45

These patterns were reflected in the fight over the Bursum Bill, introduced in 1922. The bill, which was ultimately defeated, sought to settle Pueblo land conflict with measures favoring non-Native land claims. In 1924, the Pueblo Lands Act was enacted, which was more favorable to Pueblo Indians.Footnote 46 In shorter narratives, it is tempting to date assimilation's downfall to its death throes in the late ’20s and early ’30s. A deeper dive shows that assimilationism's vulnerabilities were on display in earlier decades, too.

4.3. Strengths of Interest

Where ideology was vulnerable, interests were stronger. For thirty-seven years after Bloody Kansas, only three more states were admitted to the Union: Nevada (1864), Nebraska (1867), and Colorado (1876).Footnote 47 In 1889, North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Washington were admitted. Idaho and Wyoming followed in 1890. Utah was admitted in 1896; Oklahoma in 1907. In 1912, New Mexico and Arizona joined the Union and filled in the statehood map for the contiguous United States. Alaska and Hawaii became states in 1959.

Hoxie identified two objectives of new western members of Congress. Throughout the region, “westerners opposed any ‘meddling’ in their states’ affairs.”Footnote 48 Members of Congress—especially from the states surrounding Indian Territory and eventually from Oklahoma itself—wanted Indian lands opened to settlement quickly, and they succeeded in speeding up the pace of allotment in the 1890s and 1900s. With both agendas, westerners made arguments for “practicality” in policy, with little interest in the eastern reformers’ civilizing agenda that was embedded in OIA institutions.

As new western states joined the Union, there was turnover in congressional leadership on Indian affairs.Footnote 49 Tables 1 and 2 excerpt Hoxie's findings. In the 1880s, no western senators served as key leaders on the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. Senator Henry Dawes from Massachusetts was the powerful and experienced chair of the committee. In the 1900s, only two of the leaders were from outside the West. Of the western members, about half were from newly admitted states and about half were from older western states. Hoxie described this transition: “Once the cost-free plaything of eastern reformers, Indian legislation was becoming the special province of western politicos.… Men from beyond the Mississippi did not snatch control of Indian policy away from their eastern colleagues; it was handed to them.”

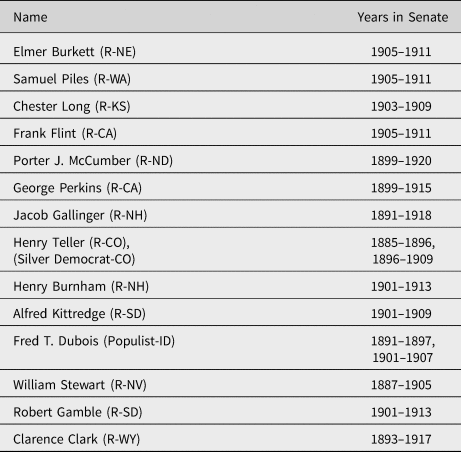

Table 1. “The Dawes Loyalists”: Senate Leaders on Indian Affairs, 1880–1885

Source: Frederick Hoxie, A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984).

Table 2. “Indian Policy Makers”: Senate Leaders on Indian Affairs, 1900–1910

Source: Frederick Hoxie, A Final Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984).

4.4. The Interplay of Three Rival Sovereigns

State politics offered political opportunities for Native Nations. This idea may seem counterintuitive because, broadly, state and territorial governments were not friends of Indians. States and territories sought to transfer Native lands into non-Native hands. They sought to apply their regulatory and police powers to Native lands and persons even when they lacked a legal foundation to do so. States used their police powers on reservations, despite the illegality of those actions, and inflicted violence. They resisted efforts to integrate Native children into local public schools. But relations between Native Americans and their non-Native neighbors were complex and ran the gamut: from “deadliest enemies” to close personal ties. Some neighbors were genuinely sympathetic to Native peoples and angered by the injustices and privations that Native peoples experienced. Other lacked personal affinity for Native Americans but valued commercial interchange, including tourism and recreation activities. Some neighbors saw opportunities to vex political or social rivals by siding with Native Nations in regional disputes.Footnote 50

Furthermore, the premise of local “deadliest enemies” was to an important degree a rhetorical device: It provided the pretense for federal absolutism on reservations. US v. Kagama ruled—and many other decisions affirmed—that because of local hatreds, the federal government had the right to plenary power, meaning that the U.S. government could unilaterally reinterpret or abrogate treaties. Tribes faced the quandary of playing their deadliest enemies against their most powerful enemy, the federal government. In effect, plenary power meant there was no limit on federal intrusion. While state governments faced a range of legal restrictions on their interactions with reservations, the federal government had virtually none. At the height of assimilation, federal officials could dictate religious practices and household structure. Federal officials could control Native Americans’ access to food and shelter. Federal officials forcibly removed Native children from their homes. Even when federal policy moved away from assimilation, case law held that the federal government could return to those practices at will.Footnote 51 Indeed, if anyone mistakenly thought the legal basis for plenary power had faded with time, in 1943, Mashunkashey v. Mashunkashey reminded all that Congress had “‘full, entire, complete, absolute, perfect, and unqualified’ … authority over tribes and individual Indians.”Footnote 52

As Native Nations looked for allies in their efforts to resist or redirect federal policies, they acted on a limited choice set. Tribal-local alliances may have had proving ground at home before they rose to the halls of Congress. Starting in the late 1800s, the OIA took major steps to increase centralization in its operations. These actions decreased place-specific influence over OIA agents’ actions. More decisions moved to DC, but both Native Americans and neighbors had a backdoor: OIA maintained a robust inspection process that was attentive to critiques of Native and non-Native locals.Footnote 53 Complaints to federal inspectors were frequent and were used as a check on agents, which made the agents cautious in exercising the full extent of their authoritarian powers. Tribes were astute at negotiations with agents. They found a variety of ways to preserve practices that, nominally, agents were supposed to obstruct.Footnote 54

In this context, inconsistent federal laws were enacted, as different groups of local non-Native Americans supported different policies. Take the case of Pueblo land in New Mexico. In multiple pieces of legislation, Congress opened various Pueblo lands to non-Native settlement. But Pueblos had victories, too, and local supporters. In 1905, Congress made Pueblo lands exempt from taxation. In 1910, Congress affirmed that Pueblos were part of Indian Country, with all accompanying rights, and out of state jurisdiction. Indeed, New Mexico Senator Bursum's efforts to shift Pueblo lands to non-Native Americans in the 1920s, which eventually failed, faced strong resistance from non-Native Americans living nearby and from other members of the New Mexico congressional delegation.Footnote 55

Hoxie offers data on this pattern in his inventory of all roll call votes on Indian affairs on the Senate floor from 1889 to 1920.Footnote 56 Hoxie's data include both bills and amendments, measures focused on Indian affairs as well as clauses focused on Indian affairs within larger measures. Using Hoxie's descriptions, I sorted the votes in his dataset into those that increased the power and resources of tribal governments and tribal members versus those that decreased the power and resources of tribal governments and tribal members. The preponderance of votes that neither increased nor decreased tribal power were about the split in federal Indian education spending between different religious dominations or between religious schools and OIA schools.

Indeed, the votes that harmed tribes’ interests declined with time. The votes that served tribes’ interests increased with time. The average vote that harmed tribes’ interests made it to the Senate floor in 1900; but even by that time, most of those measures failed. The average measure that harmed tribes’ interests and that passed the Senate appeared in 1896. In contrast, the average vote that promoted tribal interests happened in 1906. The average measure that promoted tribal interests and passed the Senate was in 1910. Furthermore, this change did not simply reflect a shift in subject area interest. About half of Hoxie's observations are on land issues. The average measure on land issues appeared in 1900; the average measure on other issues appeared in 1902.

In sum, a deeper dive into historical scholarship revealed that assimilation policy was open to attack from the late nineteenth century forward. Its reliance on ideology made it vulnerable. All the while, the growing rural western presence in Congress made interest-based federal Indian policy more tenable. Many of those rural western interests threatened Native Nations, but others were a means of political leverage for tribes.

5. Original Data Collection

My original data analysis examines witnesses at congressional hearings in order to evaluate political access. Note that a sample of hearings differs from a sample of bills. Many of the hearings were not about a specific piece of legislation: Some were oversight hearings of federal agencies; some were fact-finding hearings. Also, in the early years of records, documentation of substitute bills was incomplete. If a bill that was considered in a hearing failed to make it out of committee, it is unclear whether a similar bill went to the floor shortly afterward.

Political access does not guarantee decisive power in final policy design, of course. But it is a vital status that was not won easily. Several elements came together before a tribal leader or tribal member testified at a congressional hearing: Someone important had to know them, someone in a key role had to invite them, and the invitee had to accept the invitation. This combination of factors needed to gain a seat at the witness table speaks to the political presence required to appear before a congressional hearing. Most hearings in the sample occurred in DC, so for tribal leaders, the very practicalities of the trip would require political creativity. Scholars who have examined hearing participation, such as Fowler in her study of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, describe tribal advocates who found ways to make the trip frequently.Footnote 57 In short, a place on the hearing agenda was an accomplishment on its own.

Hearings can be important political fora even if they do not generate legislation. As Katznelson and Lapinski noted, “the record of [Congress's] deliberations, kept for more than two centuries, presents a remarkable compilation of discourse by political representatives.… [T]his archive of speech is vastly underexploited.” They continued, “the Congress literature has convincingly shown that committees possess gatekeeping authority, proposal power, and act as liaisons for the exchange of information.”Footnote 58 Hearings were a venue to advance legislation, but they also affected policies by awarding a political spotlight. Consequently, hearings can be important for the politics of position-taking, issue definition, and framing. Carlson noted that tribal advocacy before Congress was not just for the immediate purposes of proposed legislation.Footnote 59 Tribal leaders sought to change law, of course, but they also used testimony to educate policymakers and the public, challenge conventional wisdom and meanings, build relationships, and pressure executive agencies. In short, they testified to “tell and legitimize their stories.”Footnote 60

We see a powerful, disturbing illustration of the substance of an investigatory hearing in 1931 in Tacoma, Washington, by a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.Footnote 61 At the hearing, Bill Young complained about Cushman Hospital, an Indian Health Service facility that treated Native American children with tuberculosis. Young's daughter was a patient there. By the staff's own admission, they had been “whipping” children for misbehavior. Senators used forceful and meaningful language in response: They threatened action, defined issues, and articulated policy criteria.

Senator Burton Wheeler (D-MT) noted more than once that Congress could act in response:

I want to say to you and the other people in this institution that if you start in and use corporal punishment on … the children that come here for the purpose of being treated for tuberculosis, something will happen to this institution. There will be no more appropriations if I can stop them from being given here under those circumstances…. [emphasis added]Footnote 62

There is going to be a stop put to this beating up of children and particularly in these institutions. I know, very frankly, that the sentiment of Congress is absolutely opposed to this.” [emphasis added]Footnote 63

Wheeler's words had further significance because of the issue coupling that he set forth. In this time period, while a certain number of Native children were residing in federal medical facilities, far more Native children were residing in federal boarding schools. More than once, Wheeler made clear that his expectations applied not just to one hospital, or a small number of hospitals, but to schools as well:

If there is any matron around this hospital or anybody else beating up these children with a rubber hose or beating them with sticks, or things of that kind, they better be gotten rid of, because any woman who has no more sense than to be threatening children like that has no place in a hospital or school of this kind….

It is strange that in every up-to-date institution in this country to-day [sic] they do not use corporal punishment. They find other means. It is almost invariably the fault of teachers or those in charge when they have to resort to this old-fashioned way of having to deal with children. It is not being done in up-to-date institutions throughout the country anywhere. You may disagree with that, but I am telling you it is not done and it is not going to be permitted to be done here. [emphasis added]Footnote 64

Finally, Senator Wheeler and Senator Lynn Frazier (R-ND), who was also the committee chairman, articulated policy criteria that emphasized Native American rights. Wheeler remarked, “I sometimes spank my children, but I do not want somebody else doing it.” For the era, it was a rather remarkable suggestion that the rights and discretion of average Native American parents were on par with a U.S. Senator's rights and discretion as a parent. Frazier made an equally remarkable suggestion about the rights of Native children, asserting that their happiness and emotional security were important policy objectives: “It would seem in a sanitarium above all other places nothing of that kind should be used because if these children are going to improve in health they have to be under pleasant circumstances and have the confidence of the attendants and nurses.”

Did a bill emerge from this hearing? Apparently not. Did the evidence that Bill Young presented of the physical abuse of his daughter, and the ensuing discussion at the hearing, change policy? It seems reasonable to expect that the words spoken at the hearing might have had consequences for attitudes and behavior of patients’ families, and of staff and leadership within the Indian Health Service. In short, even though the hearing did not directly result in legislation, it served as a platform to threaten legislative action, define policy issues, and articulate political considerations.

5.1. Data Source

Using ProQuest Congressional, I compiled a sample of congressional hearings on Indian affairs from 1889 to 1970. Carlson noted, in her survey of existing scholarship, the absence of analyses of representative samples of congressional action on federal Indian policy.Footnote 65 ProQuest Congressional provides a database of all congressional hearings from the mid-nineteenth century forward. It tracks keywords, the title of the hearing, a brief summary of the hearing, a witness list, and brief descriptions of the witnesses. It also includes the full text of the hearing. I began with a random sample of 120 hearings on Indian affairs from 1889 to 1970. I also drew an oversample of sixteen hearings for each decade. In all, the sample netted 31,319 pages of testimony on Indian affairs. Using this text, I coded the scope and subject of hearings. I also coded the witnesses for each page. I sought to catalog the prominence of the different voices in the hearings. I offer more details about the data source in the Appendix. This dataset provides unique contributions to our understanding of the evolution of federal Indian policy and, more broadly, to our understanding both of race and western expansion in American political development.

5.2. Variables

5.2.1. Witnesses

I sorted witnesses into six categories. I identified whether witnesses were federal bureaucrats, members of Congress, non-Native Americans from near reservations, tribal leaders, tribal members, or representatives of advocacy groups that took on pan-tribal issues. For each hearing, I noted how many pages of text can be attributed to each of these categories. The final category was for witnesses that I was unable to categorize. For more details on the coding of witnesses, see the Appendix.

5.2.2. Congressional Representation

I added to the dataset the number of new western senators and the total number of western members in the House of Representatives. As the sample began, there were nineteen members in the House of Representatives from western states; by the end of the sample, there were eighty-three such members. By 1893, there were thirty-three members in the House of Representatives from the West. There were thirty-eight in 1903, fifty-nine in 1913 and 1923, sixty-six in 1933, sixty-nine in 1943, and seventy-five in 1953. The biggest change in any individual state was California; it had six members in the House in 1889 and thirty-eight in 1963. Over the sample period, delegation sizes grew modestly in Colorado, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington; combined, delegations from those states rose from two in 1889 to eighteen in 1963. On the Central Plains, delegations grew, then declined starting in 1933.

These data captured two different trends in the legislative representation of the West. Changes in the number of senators—nearly complete after the admission of New Mexico and Arizona in 1912—captured a shift of power toward western states that were very rural in their early years. Changes in the number of members from the House of Representatives, however, represented a shift within the West away from rural interests as the region urbanized. In the West today, the vast majority of non-Native Americans’ lives and livelihoods are not in reservation lands. In the rural West of the early twentieth century, the story was quite different. Even today, most reservations are located outside of urban areas. Nearly no reservations were initially sited in urban areas; recent urban sprawl has brought only a small number of reservations into urbanized areas.

5.2.3. Subject

I also coded the subject of the hearings. Most specifically, I am interested in whether hearings address land rights, which have been the fundamental source of Native-White economic competition over time. Native and non-Native American interests might align in a number of issue areas, but not land. Settler-colonizer society, especially in rural regions, hinged on the denial of Native land rights.

Land rights hearings were of several varieties. Some hearings examined or attempted to delineate property rights, which may include compensation for lost property. I also noted which hearings addressed land-based economies—farming, ranching, mining, drilling, and forestry—that were explicitly or implicitly related to land rights. A hearing could fit into more than one category.

There were hearings that addressed other topics, of course. Some hearings discussed measures to improve the health, education, and welfare of Native Americans. Some hearings discussed the operations and budget of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Some hearings addressed the functions and resources of tribal governments.

5.2.4. Scope

Next, I coded the scope of the hearings. Some hearings focused on specific, named individuals—most commonly, to resolve individual land claims. Some hearings focused on specific, named tribes. Some hearings focused on specific states or specific territories—where sometimes specific tribes were named and sometimes they were not. Finally, some hearings had a fully national scope and did not single out individuals, tribes, states, or territories.

5.2.5. Effect on Tribes

In addition, I categorized whether the hearing considered steps that would have increased tribal resources and powers, restricted tribal resources and powers, or whether the objective was unclear.Footnote 66

5.2.6. Ascendant Ideology

As an indicator of which approach to federal Indian policy had greater traction in the executive branch at a given time, I included measures of the institutional affiliations of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in the executive branch. Specifically, I coded for whether the commissioner was affiliated with an organization that promoted cultural relativism and did not problematize tribalism. These included John Collier (1933–1944), William Brophy (1945–1948), Phileo Nash (1961–1966), Robert L. Bennet (1966–1969), and Louis Bruce (1969–1970).

5.2.7. Committee Composition

I gathered membership rolls for each committee that conducted a hearing in the sample. I calculated the percent of committee members who came from states admitted after 1888.

5.3. Overall Descriptive Statistics

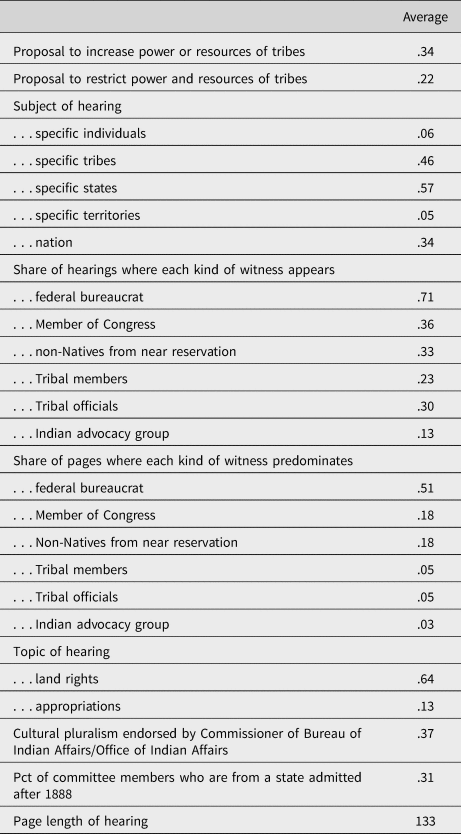

Table 3 begins with some basic descriptive statistics that can inform further empirical analysis. Note that this is an unweighted stratified sample. The basic patterns in the data are as follows.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics on Sample of Congressional Hearings on Federal Indian Policy

Data are from an unweighted stratified sample.

5.3.1. Witnesses

As for witnesses, the most common type was federal bureaucrats: They appeared at 71 percent of hearings and provided 51 percent of the testimony.Footnote 67 The head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)—known as the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) in early years—and his deputies were frequent witnesses on national policy. On hearings regarding specific tribes, it was common for the witness list to include officials in the BIA, OIA, Indian Health Service, or related agencies who worked on that reservation.

Members of Congress were scarcely silent; they gave formal testimony or provided narratives in 36 percent of hearings; 18 percent of testimony was from members of Congress.

About one-third of the time, tribal members and/or officials were present to testify; combined, they appeared at 35 percent of hearings. But the time devoted to their testimony was limited—they offered a combined 10 percent of testimony. Hearings were more likely to include tribal officials, who appeared in 30 percent of hearings, than tribal members, who appeared in 23 percent of hearings. This proportion is roughly 1:1 up through 1950 and 2:1 for the final two decades of the sample. Pages of testimony were split evenly between the two groups.

Non-Native Americans from near reservations appeared at 33 percent of hearings. For the most part, these witnesses were private citizens, although state and local officials appeared as well. Non-Natives from near reservations offered 18 percent of total testimony.

And despite the historical record's emphasis on the role of pan-tribal advocacy groups, their members were a rare presence: They appeared only 13 percent of the time and offered only 3 percent of the testimony. The National Congress of American Indians testified in the 80th, 82nd, 88th, and 90th Congresses. Other high-profile pan-tribal organizations appeared as well, such as the Indian Rights Association in the 60th and 71st Congresses and the American Indian Defense Association in the 69th Congress. Smaller pan-tribal organizations appeared, too. The Mission Indian Federation—a pan-tribal organization within California—offered testimony in the 75th Congress.

5.3.2. Subject

The data revealed the predominant theme in congressional attention to Indian affairs: land rights. In Congress, 64 percent of hearings considered questions of land rights, and 58 percent of hearings considered property rights and property claims. Some of these hearing specifically sought to delineate Native and non-Native American authority over property, such as in the 90th Congress with a hearing on whether “to authorize that lands mortgaged on the Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation in South Dakota shall be subject to foreclosure or sale in accordance with state law, and to authorize that land acquired by the Rosebud Sioux Tribe or tribal members can be held in trust by the U.S.” Other hearings considered bills to transfer certain lands from federal to tribal control, and vice versa. Hearings on allocating land claims compensation to tribes were common, especially after the creation of the Indian Claims Commission in the 1940s. The commission was authorized by Congress to determine a compensation amount to tribes for lands that were taken from them; each act of compensation required a separate allocation by Congress.

In Congress, 21 percent of hearings considered land-based economies that were explicitly or implicitly linked to land rights. I classified land-based economies as including farming, ranching, mining, drilling, and forestry. Hearings on the subject included a “withdrawal of Lands in Minnesota National Forest Reserve for Chippewa Indians” in the 69th Congress and other policies regulating tribes’ control over timber. There was an “investigation of Mineral Leases and Settlement of Estates for Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians” in the 60th Congress; actions on mining and drilling in Oklahoma appeared frequently across the sample. Also common were irrigation projects on Native lands, which appeared in multiple Congresses.

5.3.3. Effect on Tribes

Proposals that increased tribal power and resources, along with proposals that restricted those resources, were both relatively common: 34 percent of hearings in the sample considered initiatives to increase tribal power and resources. Some of these hearings were investigative and spotlighted issues of concern to tribal governments: such as an investigatory hearing in the 55th Congress on alleged “administrative improprieties” by BIA employees in Oklahoma or one in the 64th Congress on the inadequacy of medical facilities on Indian reservations. Other hearings considered specific actions that increased tribal power—such as a hearing in the 71st Congress on legislation that would add lands to the Navajo Reservation or a hearing in the 75th Congress on “legislation to extend rights to file claims against the U.S. to nontreaty bands of California Indians and to permit tribal groups to hire private attorneys for claims prosecution.”

In all, 22 percent of hearings considered restricting tribal power and resources. Some of these hearings considered bills that would limit funds available to tribal governments, such as hearings in the 80th and 87th Congresses on bills “to Terminate the Existence of the Indian Claims Commission.” Others diluted tribal lands and powers, such as a hearing in the 66th Congress on a bill to further allot the Bad River Indian Reservation.

5.3.4. Scope

As for the scope of hearings, a small number—6 percent—were about specific individuals. Those hearings tended to address the land claims of specific individuals, such as a hearing on “Issuance of a Patent in Fee to Thomas A. Pickett” in the 81st Congress. At the other extreme, 34 percent of hearings were about national policy. Many of these hearings related to the annual appropriations of the BIA. Others addressed reforms to practices nationwide, such as a hearing in the 89th Congress on a bill “to Amend the Law Establishing the Revolving Fund for Expert Assistance Loans to Indian Tribes.” The sample included hearings on proposed major changes to federal Indian policy, such as a hearing in the 64th Congress on a bill “granting Indians the Right to Select [Bureau of Indian Affairs] Agents and Superintendents” on their reservations.

But as the historical literature would suggest, congressional action on Indian affairs was predominantly localized. In all, 46 percent of hearings were about matters that affected one or a small number of tribes, such as a hearing in the 65th Congress on farmland leasing arrangements on the Umatilla Reservation, a hearing on Osage tribal member enrollment regulations in the 60th Congress, and a hearing on the “Termination of Federal Supervision Over Property of the Lower Elwha Band of the Clallam Tribe of Indians of Western Washington” in the 86th Congress.

Moreover, 62 percent of hearings addressed issues that affected one or a small number of states or territories. These included bills on specific tribes; they also included bills that affected many tribal governments but one or a small number of states, such as a hearing on a bill “to Confer Jurisdiction on the State of California with Respect to Offenses Committed on Indian Reservations Within Such State” in the 82nd Congress and a hearing on statehood for Oklahoma Territory in the 58th Congress.

6. Multivariate Regression

I used multivariate regression analysis to disentangle the multiple dynamics in these data. I expected local, cross-racial, interested-based coalitions to emerge on some issues but not on questions of land rights. Furthermore, I expected that the ability of those coalitions to turn objectives into political access would be greatest when western rural power in Congress was at its peak. To recap, the analysis tested five particular hypotheses. Patterns of western non-Native and Native American testimony should (1) parallel each other, (2) differ from patterns of federal bureaucrats and members of Congress, and (3) change when topic of hearing is land rights. Specifically, (4) as western states were admitted to the Union, access should have increased for Native and non-Native American witnesses, and 5) access should have declined as urbanization shifted attention away from (largely rural) reservations and the non-Native communities near reservations.

6.1. Dependent Variable

I considered the determinants of presence at hearings by tribal members, by tribal officials, by non-Native Americans from near a reservation, by federal officials, and by members of Congress. I considered multiple indicators of access to hearings for each group. Analysis was with OLS, except where noted.

First, I examined a basic test—whether or not anyone from a given group had at least one page of testimony in the hearing—using logistic regression. Second, I examined the number of pages in a hearing that came from a given group. I measured pages as a logged variable, for two reasons. First, I expected there would be decreasing marginal return to additional pages of testimony. The value to a group of moving from ten to twenty pages is greater than the value of moving from, say, 110 to 120 pages. Also, some of the hearings were very long and there was a long right-hand side tail to the distribution of length. The logged variable avoided distortions that those observations would otherwise introduce. To operationalize the analysis, I took the natural log of the number of pages plus one.

Third, I examined the share of pages in a hearing that came from a given group. This measure sought to assess the relative importance of a group in the hearing. I posited that fifty pages of testimony in a 75-page hearing may differ in important ways from fifty pages in a 200-page hearing. To operationalize the variable, I measured the ratio of one group's pages to all other groups’ pages in the hearing. To allow for decreasing marginal returns to the length of testimony, I used logged number of pages. More particularly, I measured

6.2. Independent Variables

6.2.1. Congressional Representation

I expect that constituencies with the greatest immediate stake in federal Indian policy received the greatest attention in Congress when the number of western states was high but the populations in those states was more rural. In the sample, two time trends are unfolding: First, new states were gaining seats in the Senate and a small number of seats in the House of Representatives. With time, while representation in the Senate remained stable, the western delegation in the House became much larger and more urban. As the West urbanized, increasing numbers of westerners found themselves removed from land-based economies and living at a distance from Native lands. I expected congressional attention to follow the constituents. I measured strong rural representation as when the number of western senators is high but the number of western members of the House is low. When the number of western members of the House is high, it serves as indicator of the extent to which urban western concerns have supplanted rural western concerns.

The existing political science literature says little about the political dynamics in the admission of these ten new states. Stewart and Weingast, as well as Murphy, focused on how the national parties managed the admission of new states so as to marshal their power on existing national issues.Footnote 68 In their frameworks, new states were not noted as bringing onto the agenda either new issues or additional perspectives on existing issues. It is worth observing, however, that Stewart and Weingast examined the postponement of admissions and not the politics after 1889. While Republicans delayed the admission of states dominated by Democrats, those territories did eventually become states in subsequent decades.

6.2.2. Subject of Hearing

Existing scholarship indicates that local Native and non-Native Americans may have had common cause on reservation social conditions, but been at odds over land rights. If so, western members of Congress had incentives to narrow access to land rights hearings. Deloria provided a flavor of these efforts at narrowing.Footnote 69 He described how, with land rights under termination policy, congressional committees valued speedy action and constrained deliberative processes. House and Senate committees conducted their affairs jointly, to condense deliberative processes. Bills emerged from committees hastily assembled and poorly conceived. In one case, the bill on Klamath termination proposed an immediate clear-cutting of the tribe's entire forest. In the absence of reflection, no one had paused to consider how flooding the timber market would harm prices for both Native and non-Native foresters, and it took last-minute intervention to revise the bill. I anticipated that this pattern of narrowing repeated itself in other land rights hearings.

6.2.3. Controls

Other dynamics were unfolding as well, of course. The model tests the hypothesis that tribal witnesses would be more likely to be invited to testify on issues increasing tribal powers and resources, and less likely to be given the opportunity to appear on issues that decrease tribal power and resources. Also, the model accounts for the hypothesis that local non-Native and Native Americans would testify more at hearings where the scope was a local issue, while federal bureaucrats would testify more when the hearing's scope was a national issue. Furthermore, the model considers whether ideological trends in the BIA affected political access: specifically, whether Native American witnesses had more access when belief in cultural pluralism was ascendant. Finally, the model accounts for the fact that appropriations hearings had unusual qualities: They tended to be lengthier and cover a wider dispersion of topics.

6.2. Results

Tables 4 and 5 report the results. I used robust standard errors clustered by congressional session. In the tables, statistical significance at the 10, 5, and 1 percent levels is indicated by *, **, and ***, respectively. First thing to note: There are two clear clusters of witnesses. Tribal officials, tribal members, and non-Native Americans from near reservations are complements, as hypotheses (1) and (2) predict. Their access rose and fell together. In contrast, federal bureaucrats and members of Congress to a degree are complements to each other but substitutes for witnesses from outside of (what would eventually become) the Beltway.

Table 4. Regressions Predicting Testimony at a Hearing: Local Non-Natives, Tribal Officials, and Tribal Members

N = 237

Table 5. Regressions Predicting Testimony at a Hearing: Federal Bureaucrats and Members of Congress

N = 237

The urbanization of the West—manifested in the increase in the number of Westerners in the House of Representatives—appears to have improved access for federal officials and members of Congress and to have decreased access for local rural constituencies, both non-Native and Native Americans. As hypothesis (5) predicts, people living on and near reservation lands—both non-Native and Native—were afforded fewer opportunities to testify on federal Indian policy, while federal officials and members of Congress testified more. Preponderantly, the effects are statistically significant.

Western political incorporation in earlier decades—manifested in the increased number of westerners in the Senate—had an effect that is conditioned by the policy content of hearings. As hypothesis (4) predicts, the number of new western senators has positive and statistically significant effects on the presence in hearings of tribal members, tribal officials, and local non-Native Americans. For both variables, the effect on the presence of federal bureaucrats and members of Congress is inconsistent.

In a parallel fashion, when hearings were about land rights, the effect on the presence of tribal members, tribal officials, and local non-Natives is positive and significant. Yet there is an important interactive effect at play. When a hearing considered land rights and when the number of newly admitted states was high, this interaction drove down the participation of tribal members, tribal officials, and local non-Native Americans; the effect is statistically significant. The effect on federal officials and members of Congress is inconsistent and mostly insignificant. It appears that, when it came to land policy, members of Congress had motives to narrow the scope of conflict and obscure Native-White conflict, as hypothesis (3) suggests.

6.2.1. Other Effects

The results also show that the policy content of a hearing mattered. If the hearing covered a proposal to increase the power or resources of tribes, then tribal members and federal officials participated more and the effects are largely statistically significant.

Also, geographic focus mattered. If the hearing considered national policy, federal officials participated more and the effects are largely statistically significant. If a hearing considered policies affecting one or a small number of tribes—which was the more common type of hearing—non-Native American locals participated less and with statistically significant effects. When hearings were about one or a small number of states, non-Native locals participated more and the effects are statistically significant. When hearings were about one or a small number of territories, then non-Native locals, tribal officials, and tribal members participated more. The effects are statistically significant for three, two, and one of the models, respectively. Ascendant ideology in the executive branch was consistently insignificant. In some eras, advocates of cultural pluralism led the BIA. These key changes in power did not appear to alter the results.

6.2.2. Alternate Specifications

Through what pathways did western members of Congress exercise their power differently? One possible mechanism: They joined the committees that shaped federal Indian policy. If members from formerly unrepresented places brought new priorities to Congress, committees would be a place they might put those priorities into action. These members could shape the agenda of committee hearings, thereby altering political access to both legislative and oversight functions. It seems natural that western members of Congress would be more apt to secure access to hearing agendas for their non-Native American constituents. Were they more apt to provide the same opportunities to Native Americans, too?

To test this hypothesis, I re-specify the model to measure the effect of committee composition. In particular, I consider whether access to hearings was influenced by the percent of committee members who were from the states recognized after 1888. In the sample, there are some hearings with no such members. The two committees in the sample with the largest share of members from the post-1988 states are the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs in the 79th Congress, 2nd Session (79 percent) and in the 70th Congress, 2nd Session (77 percent). Because there are some hearings for which I do not have committee composition, the sample size drops to 225 in this specification. Tables 6 and 7 present the results.

Table 6. Regressions Predicting Testimony at a Hearing: Local Non-Natives, Tribal Officials, and Tribal Members

N = 225

Table 7. Regressions Predicting Testimony at a Hearing: Federal Bureaucrats and Members of Congress

N = 225

The effects are consistent with expectations. As with earlier findings, two clusters of results emerge. Non-Native Americans from near reservations, tribal members, and tribal officials form one cluster: When more committee members were from post-1888 states, these three groups were more apt to testify. The effect is statistically significant across eight of the nine models. Members of Congress and federal bureaucrats form another cluster: For these two groups, the effects are of mixed signs and statistically insignificant. There are a variety of pathways through which members of the 1889-and-beyond states could alter outcomes; it appears that their committee participation was one of them.

7. Textual Corroboration

The text of the hearings provides important corroboration of the regression findings. Non-Native Americans living near reservations emphasized the interests they shared with Native Nations. They attested to the competence of Native peoples. They insisted that reservations needed more resources from the federal government. They also made the case that federal power over reservations had been misused and should be restricted. Non-Native locals also spoke passionately about deep human suffering, appalling social conditions, and federal mismanagement on reservations. I am not at all suggesting that non-Natives were especially morally elevated. They did, however, voice some truths that the architects of assimilation policy did not want to hear.

A number of non-Native American locals emphasized their shared and intertwined interests with Native peoples. For example, in 1898, Reverend W. W. Caruthers from Fort Sill, Indian Territory, remarked:

The railroad coming right alongside of the reservation brought small towns and stores where the Indians could buy their goods a great deal cheaper…. These towns want the Indians and the Indians get their goods there cheaper than they can get on the reservation; so it seems to me a common sense argument that they should be allowed to trade there.Footnote 70

Similarly, in 1931 Clyde Ely, former editor of Gallup Independent (NM), observed economic interdependence:

Especially as to the Navajos we feel that we are bound up with the Navajos economically and otherwise and that their prosperity and progress is reflected in our business and in the general prosperity of the community, including all the whites….

Our prosperity is directly dependent upon the prosperity of the Navajo Indians. There is no question about that; his blankets, his silverware, his wool. For instance, when they have a good year the merchants have plenty of money in Gallup because the Indians spend it readily.Footnote 71

Caruthers, Ely, and other witnesses emphasized shared, cross-racial economic interests in the rural West. One implication of their economic arguments was that Native Americans were competent trading partners, and indeed we see such an argument made explicitly. In a 1904 petition, a group of ministers in Indian Territory argued that Native peoples are highly competent:

It is very natural to suppose that Indian Territory is full of Indians, and that the Indian is an uncivilized and unenlightened man. This is far from being true. Even the full-blood Indians of Indian Territory have had school advantages for half a century, many of them are educated, and, because of their experience, a great body of them are intelligent people, all have been self-supporting all of their lives without aid from the Government.Footnote 72

This view ran counter to the assimilationist vision that Native peoples were not fit to manage their affairs on their own.