Hanover 26 Octr 1809

Honoured Sir

I was a few years back a slave on your property of Houton Tower, and as a Brown woman was fancied by a Mr Tumming unto who Mr Thomas James sold me; on his leaving the Estate he took me with him to Trelawny, where he died, and left me very well situated. But Mr T. James purswaded me to return to Houton Tower as every relation I have in the world are there, so Sir by his perswasions I returned, and he appointed a place for me to build my house; accordingly I built a house, but finding it too small to contain me and two black Brown sisters I have on the Estate I build another for my self in particular, and was in all respects very comfortable; Untill Mr James's death. Then Mr Kircady the Overseer turned very severe on the Negroes on the property, and they could find no redress, for on Complaint to Mr Brown the AttornyFootnote 1 he punished them the more severely, that the poor critures are harrased out of their lives, many dying; On Mr John H. James coming to the Island he took a look at the Estate, but did not have the Negroes called up in the latter end of August, the Negroes went on a Sunday to Mr James at Green Island, seeking for redress, from there so severe usage for which reason, Mr Brown & Mr Kircady took it into there heads that I had perswaded the Negroes, to aply to Mr James, and early in the morning came and pulled down both my houses, and took away the Timbers; Now Honoured Sir as I was sold of the property free I mought have been disc[ou]raged, as having no property or wright what has my two Sisters and there young children no wright to a house on their Masters Estate, their children are young and left without a shelter.Footnote 2 I was a great help to them having a ground and garden with provisions which mought have been given to them, but it pleased your Attorny and Overseer to destroy every thing plowing up the garden and turning the Stocks into the ground or provisions, so that I am not only a sufferer but your poor negroes, are deprived, of the means of subsistence. Honoured Sir this is the truth and nothing but the truth, your negroes are harrased floged, and drove past human strength, with out any redress, to complain to an Uncle against his nephew is needless, it's not my own immediate case that make me address this to you, but my suffering family, who can not go otherwise as I am obliged to do.

Thus Sir I have laid down the state of Estate of Houton Tower, which if not soon redressed you will have no slaves, to work on the Estate. I must beg my Honoured Master, for to give me a little spot somewhere on the Estate, for I do not wish to go from my family, as they want every assistance I can give them; I feel for you Sir as if I was still you slave; and as Mr Kircady says he will make your people sup sorrow by spoonfuls, they really do for he [verifys] his words.

With all respect I am Honoured Master

Your most Obd’ Humble Servant

Mary WilliamsonFootnote 3

In 2016 I was contacted by a student, Tabitha James, who reported that she had been cataloguing ‘my family's historical documents which I found in our attic’, including material on Jamaica and slavery.Footnote 4 A few weeks later she brought me a bundle of around fifty documents including twenty-seven letters written by her relative, Haughton James, between 1761 and 1812. The collection records James's voice and preoccupations over decades. Among James's many letters was the single letter from Mary Williamson reproduced above, which she in 1809 addressed to James in London.

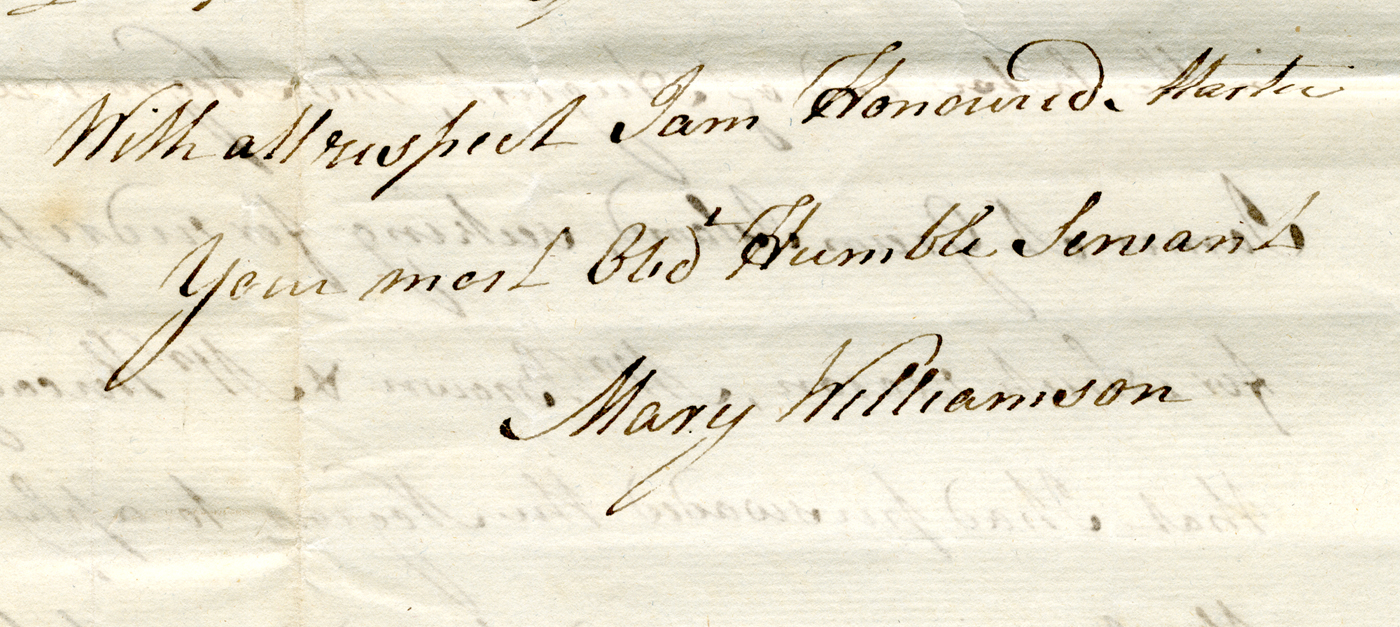

Mary Williamson's letter brings to mind Carolyn Steedman's description of the archive as a place of social historians’ dreams, where we hope and wish that ‘ink on parchment can be made to speak’.Footnote 5 It gives us Williamson's signature (rather than ‘her mark’) (Figure 1), her stylish handwriting, her unorthodox spelling, her prose, her account of her life and relationships with others, and her insights into life at Haughton Tower. The dynamics of slave societies and the priorities of centuries of archiving have led, as Marisa Fuentes argues, to the systematic absence of sources ‘written by … enslaved person[s] or from their perspective’.Footnote 6 In this context, Mary Williamson's letter is extraordinary.

Figure 1 Mary Williamson's signature on her letter to Haughton James. Reproduced with the permission of Melissa James.

Williamson's letter sheds light on many preoccupations of recent historians of slavery. In particular, it speaks to our understanding of white men's assumed sexual desire for ‘brown’ women; of the pervasive sexual coercion underpinning Atlantic slave societies; of plantation managers’ use of violence; and of enslaved people's tactics in combatting that violence. The letter also suggests an avenue of enquiry that historians have neglected: the significance of connections among adult sisters, and, more generally, siblings. Discussions about the family lives of enslaved people, like those about family history more generally, have focused on parent–child and conjugal relationships. But when we look again at evidence from Jamaica and other slave societies, we see that Mary Williamson's important connections to her sisters were not unusual. This frequently lifelong affiliation, which often outlasted ties to parents, children or spouses, provided critical support and solidarity to many enslaved and freed people. Williamson's connection to a white man was merely one among many human connections, while ‘family’ meant, primarily, horizontal relationships among sisters. The historiography of the British Empire has increasingly emphasised the significance of extended family links in the organisation of imperial trade, government and culture. Empire families organised themselves through networks of siblings and cousins, parents and children, over large distances and across generations, circulating property and information; the James family is an excellent example.Footnote 7 Mary Williamson's letter suggests the parallel importance of extended family ties to enslaved and freed people in Jamaica.

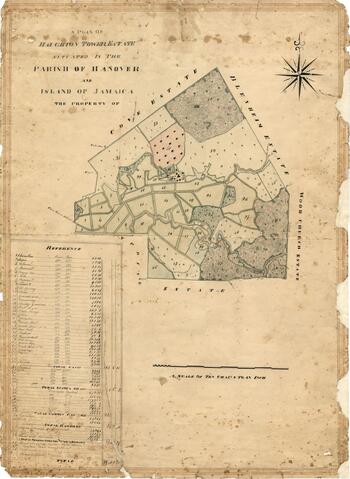

Mary Williamson and Haughton James lived through a time of rapid change for Jamaica and its relationship to Britain. We don't know when Williamson was born, but James's life tracked the rise to dominance of Jamaica's sugar industry, as well as the period during which it began to be threatened. James's birth in 1738 took place shortly before the end of the long-standing war between British settlers and the Maroon communities who occupied the Jamaican interior.Footnote 8 After the war ended in British–Maroon treaties that provided security for both settlers and Maroons, the land devoted to sugar agriculture rapidly expanded, supplying an apparently limitless demand for the sweetener in Britain and beyond. Planter families like that into which James was born were well placed to take advantage of the boom. Sugar production increased rapidly, as did the importation of enslaved Africans, creating a society intensely dependent on racial slavery. The richest men in the British Empire built their wealth on Jamaican property, and most of all on property in intensely exploited human beings.Footnote 9 In 1810 Haughton James owned 257 people who lived, enslaved, on Haughton Tower estate in the Western Jamaican parish of Hanover (Figure 2).Footnote 10

Figure 2 Map of Jamaica, 1804, showing location of Haughton Tower Estate. Map by Kacper Lyskiewicz.

When Mary Williamson wrote to Haughton James the year before, though, men like him whose wealth depended on Jamaican slavery could no longer feel certain that their power would persist indefinitely. The anti-slavery revolution in next-door Saint-Domingue and the establishment of the independent black republic of Haiti brought home the fact that the profits of sugar-based slavery could only be sustained through enormous levels of repression. Regular plots and rebellions in Jamaica also made this clear. A growing population of free people of colour – people like Mary Williamson – presented a challenge to the equation of whiteness and freedom on which Jamaican slavery was founded. In Britain, the movement against the slave trade had, after two decades of intense campaigning, recently succeeded in getting Parliament to pass the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1807. The Act called into question the economic and social model on which Jamaica had been built. That model depended on access to endless supplies of enslaved Africans, often captives in war, who were brought across the Atlantic to take the places of those in Jamaica who died. Without an external source of population or a radical change in the organisation of everyday life, this system was on the verge of becoming unsustainable. Mary Williamson wrote to Haughton James at a time when everyone in Jamaica was responding to these new realities.Footnote 11

James received Williamson's letter as an old man of seventy-one. He had owned Haughton Tower estate since his father's death when he was only two years old.Footnote 12 James was born in Jamaica, descending on both sides from some of the earliest English colonists on the island.Footnote 13 His father and grandfather were resident planters and merchants. The younger James, though, left Jamaica at the age of seventeen to go to Oxford University, and seems never to have returned.Footnote 14 After a period on the ‘Grand Tour’, he sold his family's Spanish Town home, and settled permanently in Piccadilly.Footnote 15 James made the transition to absenteeism that was the goal of many landowning Jamaican families. Like many absentees, he managed his Jamaican property primarily through men to whom he was connected through kinship.Footnote 16

It is unlikely, then, that Mary Williamson ever met Haughton James. Nevertheless, she knew who he was and how to send a letter to him, and thought it worth the trouble of doing so. Her life as a free woman had enabled her to become literate and to understand the conventions of letter writing and posting, but she introduced herself through her status as a former slave.Footnote 17 At the end of her letter, in order to drive home her appeal, she wrote that she ‘feel[s] for you Sir as if I was still you[r] slave’. Williamson's phrasing drew on a discourse that asserted the ties of dependence and responsibility that allegedly bound master and slave, and infused these bonds with emotional rhetoric, hoping Haughton James would feel obliged to respond.

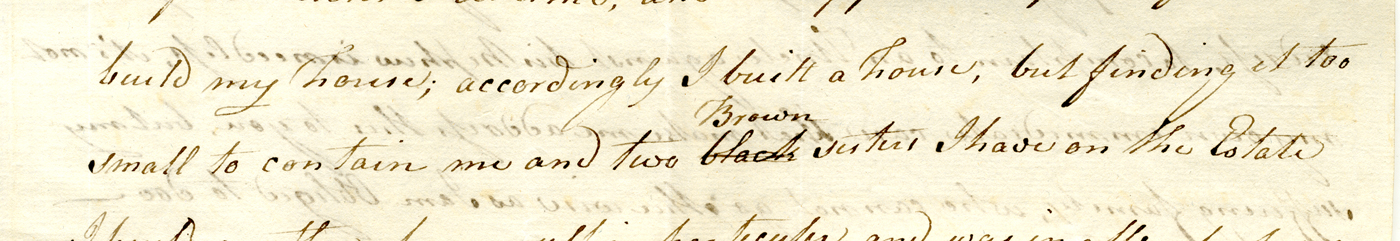

In contrast to our relatively abundant knowledge of Haughton James, we know little about Mary Williamson. We do not know when she was born, how she spent her adolescence and young adulthood, or who her parents were. The only clue to the latter is in her self-description as a ‘Brown woman’, which reveals that she had European as well as African ancestry. ‘Brown’ was and is a common Jamaican term for so-called ‘mixed’ descent. The only correction in Williamson's letter suggests the importance of the status difference between ‘black’ and ‘brown’, as well as the permeability of the boundary between them: in referring to her sisters, Williamson first wrote ‘black’, then crossed this out and instead wrote ‘Brown’, with an upper case B (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Part of Mary Williamson's letter, showing ‘black’ struck through and replaced with ‘Brown’. Reproduced with the permission of Melissa James.

Williamson's birth into slavery means that her mother was certainly enslaved, since that status was transmitted through the maternal line. Her father, grandfather, or perhaps great-grandfather (or more than one of them), must have been a free white man. Perhaps – but this can be no more than speculation – he was the James Williamson who filed Haughton Tower's accounts in 1760 in his role as the estate's bookkeeper.Footnote 18 Whoever Mary's white ancestor was, he did not free his mixed-race child. Nor were Mary's ‘brown’ sisters freed by their white ancestor. This was not unusual. Birth rates of brown or ‘coloured’ children far exceeded manumission rates.Footnote 19 Some white men demonstrated concern for and interest in some of their mixed-race children, leaving them bequests in their wills and sending them to Britain to be educated. Collectively, white men only cared for a small minority of those whom they fathered.Footnote 20

Williamson was not freed by her father, but wrote in 1809 as a free woman. By her own account, she acquired her freedom when she ‘was sold of the property free’ by the attorney, Thomas James, to Mr Tumming, who ‘fancied’ her. Two documents confirm this in broad outline though not specifics: the will of James Tumming of Hanover, and Mary Williamson's manumission record. According to these documents, Tumming never bought Williamson, who was still owned by Haughton James when Tumming died. In his will, Tumming left £100 sterling to ‘Mary Williamson belonging to Haugton [sic] Tower Estate in the parish of Hanover the property of Haughton James’. The money was to be paid to her twelve months after Tumming's death ‘for the purpose of purchasing her manumission’.Footnote 21

Using this money, Mary Williamson acquired her legal freedom. Her manumission document, dated 6 November 1802, records Haughton James's declaration that ‘I … have Manumized Enfranchised and forever set [Mary Williamson] free.’Footnote 22 Using formulaic language that appears repeatedly in Jamaican manumission records, the deed defines Williamson's freedom as being ‘of and from all manner of Slavery Servitude and Bondage to whatsoever which my heirs executors and administrators … could or might Claim Challenge or Demand’. Williamson's manumission, like all manumissions, had to be recorded to protect her against future claims of ownership by her former owner's family.Footnote 23 Despite the document's rhetorical benevolence, from the point of view of Haughton James and his attorney Thomas James this was a commercial transaction, little different to a sale. The Jameses received £140 in Jamaican currency – equal to the £100 sterling that James Tumming had left Williamson – as ‘consideration money’ for Williamson's freedom.Footnote 24 With £140, the Jameses would have been able to replace Williamson with another enslaved person, and probably have money left over. The sum was at the high end of the range of prices for enslaved people in Jamaica in the first decade of the nineteenth century, usually charged for Jamaican-born people aged between twenty and thirty.Footnote 25

I have not located any further information about Tumming, but it is safe to assume that he was white. Mary Williamson's statement that ‘as a Brown woman’ she was ‘fancied by’ him, without describing his race, suggests whiteness, in the context of the deeply engrained Jamaican assumption that white men would be attracted to brown women. For her and, she assumes, for Haughton James too, it is self-evident that ‘as a Brown woman’ she would be ‘fancied’ by a white man, and that this ‘fancying’ would lead to her sale to the man in question. Williamson presents this transaction as normal and unremarkable. The absence of racial designation in Tumming's will also suggests that he was white.

The discrepancies between the account in Williamson's letter and in the manumission record and will suggest that Tumming's claims on Williamson during his lifetime were informally negotiated between him and Haughton James, who continued to be her legal owner. Williamson's views on and experience of the situation are hard to discern. However, Tumming's testamentary insistence that she not receive the money to buy her freedom until a year after his death suggests that he wanted to maintain control of her from beyond the grave. Williamson's description of herself as having been ‘sold … free’ is thus revealingly descriptive of the in-between status she experienced through her relationship with Tumming, something she shared with people on the path to manumission in many slave societies.Footnote 26

Mary Williamson's life followed a trajectory that is familiar to the point of cliché. By the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, the figure of the mixed-race enslaved or freed woman who is sexually involved with a white man was everywhere in writing about slave societies. Planter intellectuals like Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry, Edward Long and Bryan Edwards viewed white men's attraction to mixed-race women as a problem to be solved.Footnote 27 Nineteenth-century novels from and about the Caribbean almost without exception included examples of such relationships, often presenting them as romantic but doomed.Footnote 28 In visual culture, paintings by Agostino Brunias emphasised the desirability of the mixed-race woman.Footnote 29 All of these, and many other fictional, non-fictional and visual representations of Atlantic slave societies, place sex between white men and enslaved or freed mixed-race women at the heart of their depictions of slave society. As Lisa Ze Winters has recently argued, the figure of the ‘free(d) mulatta concubine’ was ‘constitutive of the African diaspora’.Footnote 30

Many of these and other depictions of mixed-race women disavowed what was also known about slave societies: that they were worlds in which women experienced pervasive sexual coercion, from their enslavement in Africa, through the decks and holds of slave ships, and on the plantations and in the towns of the Americas.Footnote 31 It was within this culture of assumed white male sexual entitlement that James Tumming and Mary Williamson became … well, what did they become? There are no neutral words to describe what Williamson was to Tumming, or he to her. Historians have chosen from among a series of unsatisfactory terms for Williamson's position, including concubine, paramour, mistress, mate, housekeeper, lover, partner or (occasionally and recently) sex slave; and have described the connections and encounters between men and women like Tumming and Williamson as liaisons, relationships, unions, partnerships, affairs, concubinage, interracial sex, marriages, and rapes.Footnote 32 The language available tends to fall on one side or the other of a binary division between choice and coercion that fails to convey the complexity of the context and situations that it is used to name. ‘Partner’ or ‘lover’ suggests a relative equality that is not attested to by the documents or historical context; ‘concubine’ and ‘paramour’ are too easily read as exoticising and Orientalist. ‘Housekeeper’, the term most widely used in this period in Jamaica, ‘served’, Brooke Newman points out, ‘as a discursive sleight of hand’ to disguise ‘deeply exploitative relationships between men and women who occupied asymmetrical racial, social, and gender positions’.Footnote 33 ‘Rape’ often accurately describes specific incidents of sex in societies dominated by slavery, but we know too little about Williamson's interactions with Tumming to be confident using it in that context. Historians cannot avoid choosing terms to name the phenomena that we write about, yet our choices inevitably imply conclusions about the extent and significance of inequality, choice and coercion within those contexts. This is so even when we write in order to raise questions about that inequality, choice and coercion. Bearing these points in mind, here I use ‘connection’ or ‘relationship’ as the most neutral terms possible, and without prejudging the nature of Mary Williamson and James Tumming's connection and relationship.

The pioneering Jamaican historian Lucille Mathurin Mair presented a common view in describing women like Williamson as ‘females slaves’ who ‘unquestionably benefited from their intimate associations with whites, which facilitated the granting and the purchasing of freedom’.Footnote 34 More recent studies have complicated this interpretation, emphasising that, as Sue Peabody puts it, ‘one of the master's essential prerogatives’ in slave societies across the world ‘was sexual access to his female servants and slaves’ and that as a result enslaved women never ‘consent[ed] as a peer’.Footnote 35 More broadly, sexual access to enslaved women was the prerogative of all white men, as long as the women's owners did not object. Even defenders of slavery sometimes admitted this. For instance, a naval officer stationed in Jamaica agreed that it was ‘common when an English gentleman visits a planter's estate to have offered to him black girls’, although he sought to reintroduce the question of consent by stating that the ‘girls’ were ‘not constrained to come’.Footnote 36 Peabody adds that some women could negotiate specific benefits in this context, sometimes including freedom for themselves and (more commonly) their children.Footnote 37 Such negotiations constituted a specific form of what Deniz Kandiyoti refers to as ‘bargaining with patriarchy’ in which women ‘strategize within a set of concrete constraints … to maximize security and optimize life options’.Footnote 38

Whatever term we use to describe it, we cannot know whether Mary Williamson actively sought out her connection with James Tumming, or if, on the other hand, he used, threatened or hinted at the possibility of physical force or other negative consequences to compel her sexual compliance. Or, indeed, whether both these dynamics were in play. Rather, in the power-laden context in which their relationship began, in which he had freedom and financial resources and she was a slave, it makes little sense to frame a sexual relationship between them in terms of the presence or absence of choice or consent, let alone of her sexual desire or satisfaction. As Saidiya Hartman puts it, ‘concepts of consent and will’ become ‘meaningless’ in the context of slavery.Footnote 39 Moreoever, these are terms that themselves need to be historicised.Footnote 40 The irrelevance of a framework focused on choice and consent is clear from the letter, which does not invoke these terms or any related concept in describing Williamson's connection to Tumming. Instead Williamson presents herself as, literally, a commodity: he fancied her, bought her (or bought her freedom), took her with him, and that was that.

Williamson noted that her connection to Mr Tumming, a man who was not her owner, had led to important material consequences. But when their relationship began, her freedom was by no means certain. In making a ‘bargain with patriarchy’, that is, Williamson had no means of ensuring that the other side of the bargain would be kept. Another contemporary Jamaican example provides a sense of alternative outcomes. In 1800 Annie, an enslaved woman living on Rozelle (also spelled Roselle) estate, St Thomas in the East, was pregnant with her fifth child. Archibald Cameron, the overseer and the children's father, proposed to the estate owners that he pay £360 sterling (around £500 Jamaican currency), much more than the cost of Mary Williamson's manumission, for Annie and her children. Annie's owners initially told him that this was not enough; they asked for a payment equivalent to the cost of a ‘prime slave’ – around the £100 sterling paid for Williamson – for each individual purchased, of whatever age, plus £10 for Annie's unborn child.Footnote 41 This would have totalled £510 sterling, an enormous sum, which Cameron said he could not afford. The next letter that mentions Annie, five years later, states that Mr Cameron ‘changed his mind’ and did not complete the purchase, and that Annie was in the local workhouse (prison) because she had created a ‘very unpleasant situation for some time past’ on the estate.Footnote 42 The letters provide no details of this ‘unpleasant situation’, but it is easy to imagine that Annie responded with anger and a sense of betrayal, both at Cameron's refusal or inability to free her and at the estate's insistence on such a high price. In the context of a historiography that often frames women's involvement in relationships like Annie's with Mr Cameron, or Mary Williamson's with James Tumming, as calculating moves that led to their freedom, it is important to recognise the circumstances in which women did not become free, alongside the precariousness of freedom when it was gained.Footnote 43

The situation of an enslaved woman named Catherine Williams provides further context for understanding the constraints surrounding Mary Williamson's connection to James Tumming. Catherine Williams's circumstances suggest what might have happened should Williamson have refused to be the object of Tumming's ‘fancy’. Williams was a member of a missionary congregation in Jamaica in the late 1820s and 1830s. She was flogged and imprisoned because (as a missionary put it) ‘the overseer wanted her to live with him in a state of fornication, and … she would not do it’.Footnote 44 Abolitionists publicised the case by framing it in moral terms, suggesting that Catherine Williams refused the overseer because she was a Christian convert. No doubt this was important. But this evidence also suggests the possibility, and the consequences, of not taking the path that Mary Williamson took, and thus the limits both of Williamson's choice and her opportunity. Catherine Williams's story demonstrates that, although being ‘fancied’ by a white man could lead to free status, an enslaved woman who was the object of a white man's desire had as much choice in what happened next as did an enslaved man instructed to boil sugar. In either case, someone might comply hoping to improve their life; they might gain pleasure or satisfaction from doing so. Another individual in similar circumstances might resist or refuse – and that refusal or resistance would likely have consequences. Like the work of boiling sugar, the affective, intimate and sexual labour of Mary Williamson and women like her was integral to the functioning of Atlantic slave systems.Footnote 45

Like most people in their circumstances, Mary Williamson and James Tumming did not marry. As one observer put it, it was ‘not the custom of the country’ for brown women to marry white men.Footnote 46 This ‘custom’ of non-marital relationships made brown women's freedom limited and vulnerable.Footnote 47 When Tumming died, Williamson did not inherit sufficient property to become financially secure. The residue of Tumming's estate went to his two sons, Henry and James Tumming. His will does not mention their mother, but it is unlikely that they were Mary Williamson's children. If they had been, they would have been enslaved and Tumming would have needed to provide for their manumission. That they bear his name also suggests that they were the children of marriage to a white woman. Tumming thus followed the widespread white Jamaican inheritance practice made possible by the fact that white–brown relationships did not involve marriage.Footnote 48 Married men could not easily disinherit their wives, but men who lived with women without marrying them were not obliged to provide for them in their wills.Footnote 49 Mary Williamson's self-description as ‘well situated’ obscures her relative poverty, which may have been one reason she moved back to Haughton Tower.

For all its resonance with both historians’ and popular understandings of slavery, Mary Williamson's connection to James Tumming was only one element of her story, and not even the most important. Her letter emphasises her place within a broader world of human relationships. It demonstrates that the ties that connected her to her family of birth were of the utmost practical and emotional significance. She chose to move back to the site of her own enslavement because of family ties: because ‘every relation I have in the world are there’. Especially important was her connection with her two sisters. After Tumming's death they were her community, the people she wanted to be close to. She lacked the resources to free her sisters, but was able to support them materially by ensuring that they had good-quality housing. She notes that she was ‘a great help to them having a ground and garden’, and that she grew and supplied them with provisions. In Jamaica, enslaved people worked long hours to produce sugar and other staple crops. But they also depended on the subsistence food crops they raised in hours squeezed around the edges of the staple crop working week.Footnote 50 In such a context, having a free relative who was not compelled to do plantation labour and who could devote more of her time to growing food could have made a significant difference to Williamson's sisters’ quality of life and level of nutrition. An individual woman's connection to a white man could have long-term consequences not just for her, but for her broader network of kin.Footnote 51

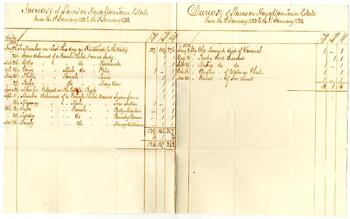

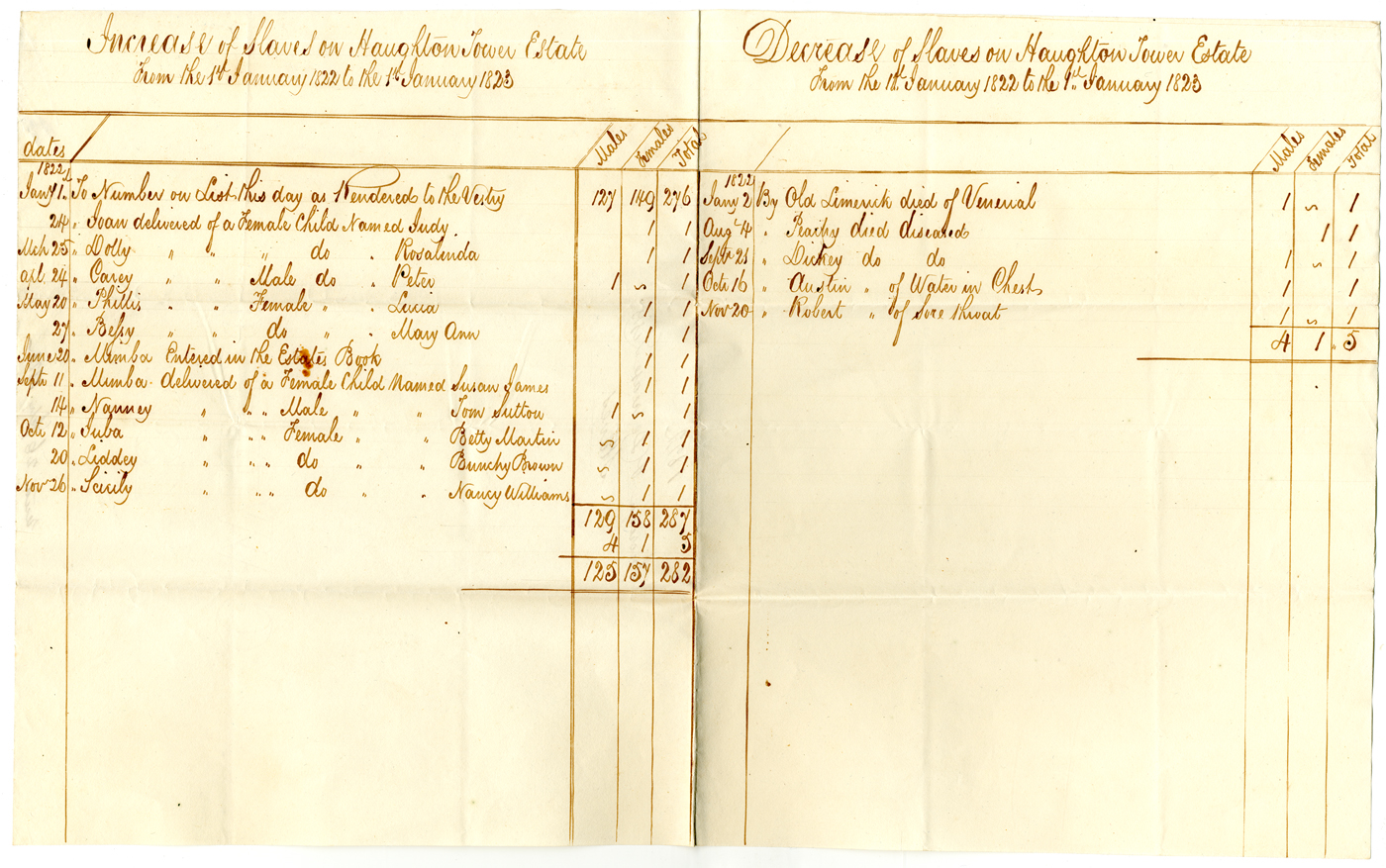

Sisterhood has been a powerful metaphor in the study of slavery ever since the abolitionists used the slogan ‘am I not a woman and a sister’.Footnote 52 But this slogan is generally understood as a metaphor about connections and solidarities, including hierarchical ones, among women who were not literally kin. Mary Williamson's relationship with her sisters directs us to the more literal meaning of sisterhood. It reveals an aspect of enslaved people's family lives that is hard to see in the routine administrative documents of Caribbean slavery. These documents include repetitive lists of slaves, series of names that were created to clarify and facilitate the ownership and management of people.Footnote 53 Such lists tell us little about the lives and relationships of the people named. Sometimes they include mother–child relationships, because those who owned enslaved people were interested in understanding the ‘increase’ of their property. The Haughton Tower document ‘Increase of Slaves … from the 1st January 1822 to the 1st January 1823’, listing in tabular form the women who had babies with the dates of birth, names and sex of those babies, is typical of the genre (Figure 4). Such documents can enable historians to identify groups of children with the same mother, although not easily: they do not highlight these relationships, certainly not into adulthood. Nor have historians paid much attention to sibling relationships, either in slave societies or elsewhere, perhaps because we also struggle to look beyond the logics of property that led to the creation of the records.Footnote 54

Figure 4 Increase of Slaves on Haughton Tower Estate from the 1st January 1822 to the 1st January 1823. Reproduced with the permission of Melissa James.

Nevertheless, Mary Williamson's letter is far from unique in highlighting the significance of sibling bonds. Other documents provide examples of enslaved siblings in Jamaica helping and supporting one another. Jane Henry, for example, was an enslaved woman who in 1831 sought out a spiritual healer to try to cure her sick adult brother.Footnote 55 John Nunes and Sarah Williams were a brother and sister who cooperated with one another to care for their elderly sick mother, Tabitha Hewitt, and to protest to the local magistrates about the lack of medical care provided for her by their master.Footnote 56 Another brother-and-sister pair, Henry Williams and Sarah Atkinson, were both members of the Methodist missionary church in Jamaica, and together protested their master's efforts to prevent them worshipping.Footnote 57 Advertisements for runaways sometimes refer to people as likely to be in places where they had a brother or sister, such as the North Carolina slaveholder who in 1814 advertised for a man named Spencer: ‘I rather expect he will make his way for the Catawba river, in the extremity of this State, where he has a brother and sister.’Footnote 58 These examples suggest that for many enslaved people, relationships between siblings persisted into adulthood and provided mutual support and responsibility. Williamson's letter also suggests the importance of kinship between freed people and those who remained enslaved. While some free people of colour built a community that emphasised their respectability and distinction from enslaved people, the less-visible majority were more like Mary Williamson: only a step away from slavery themselves, and with many personal, social and emotional connections to enslaved people.Footnote 59 An 1826 report stated that more than three-quarters of Jamaican free people of colour were ‘absolutely poor’.Footnote 60

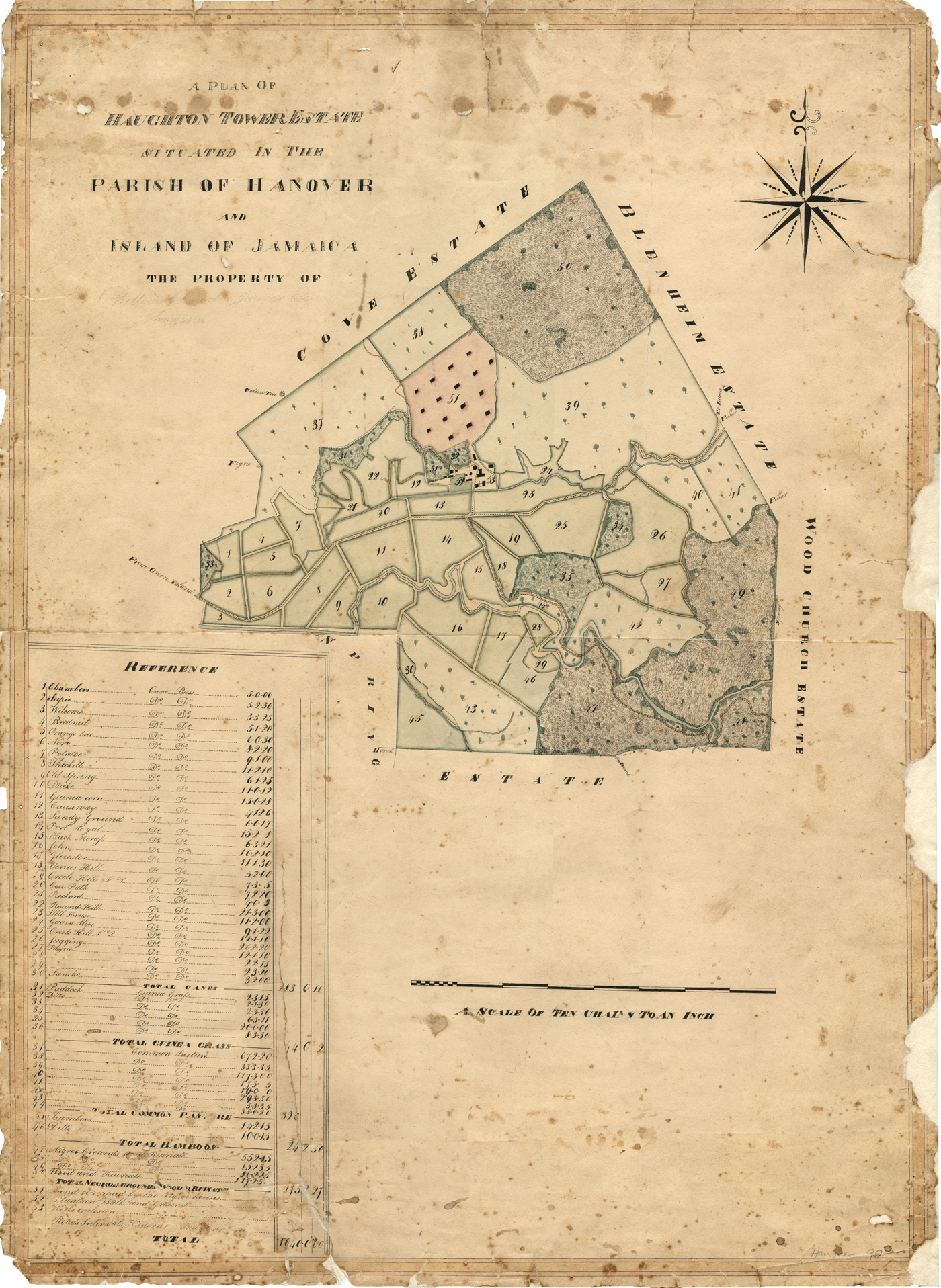

In order to be close to her family, then, Mary Williamson moved back to Haughton Tower estate, where she lived as a free woman, in her own house, with access to a provision ground, and in close proximity to her sisters, nieces and nephews. No evidence survives of exactly where on the estate Williamson's house and those of her sisters were located; most likely they were part of a group of houses on a slope leading up from the estate's sugar works, labelled on an early nineteenth-century estate map as ‘land occupied by the Negroe houses’ (Figure 5). By the time Williamson wrote to Haughton James in late 1809 she had been living near her sisters on Haughton Tower as a free woman for at least five years.Footnote 61

Figure 5 A Plan of Haughton Tower Estate situated in the parish of Hanover, the property of William Rhodes James Esquire. This plan dates from the early nineteenth century. Mary Williamson's house was probably in the steeply sloping area labelled 15, close to the sugar works. The area is described in the legend as ‘land occupied by the Negroe houses’. Courtesy of National Library of Jamaica.

Previously at least partially dependent on Tumming, on her return to Haughton Tower Mary Williamson became dependent on the goodwill of another white man, this time Thomas James, Haughton James's cousin and the estate's attorney.Footnote 62 It was he who ‘purswaded’ her to go back to Haughton Tower, and allowed her to build her house there. When Thomas died in late 1804 or early 1805 his elderly brother, William Rhodes James, became the new attorney and either appointed or reaffirmed William Kirkaldy as overseer. William Rhodes James himself died in 1807; he was replaced by a Mr Brown.Footnote 63 Around this time, the situation took a dramatic turn for the worse. As Williamson put it, now ‘Mr Kircady the Overseer turned very severe on the Negroes on the property.’ Kirkaldy's severity was supported by Mr Brown, who refused to recognise the Haughton Tower residents’ grievances, instead inflicting violence on them [‘punishing them’] for complaining. Williamson stated that enslaved people on Haughton Tower were ‘harrased floged, and drove past human strength, with out any redress’; and that Mr Kirkaldy threatened to ‘make your people sup sorrow by spoonfuls’. Kirkaldy and Brown installed a new regime that relied more openly on terror and violence than before.

This change went beyond variation among management styles. The turn to ‘severity’ on Haughton Tower took place at the same time as the passage of the British Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, which from 1 January 1808 made the importation of new captives from Africa into the British colonies illegal. Advocates of abolition argued that it would lead to the improvement of the conditions of enslaved people, because slaveholders would be forced to provide better living standards once slaves could no longer easily be replaced.Footnote 64 On Haughton Tower at least, the consequences seems to have been the opposite. Abolition brought home to managers like Kirkaldy and Brown the fact that they and their allies no longer controlled the political process. The vindictive acts of retribution by Haughton Tower's managers make sense in this context of their own declining power and as a technique to re-establish their control over the estate at a moment when it was contested.

Kirkaldy and Brown could reasonably expect Haughton James's support. At times over the previous decades James had expressed concern for the well-being of the people over whom he claimed ownership. In 1787, in the face of abolitionist criticism of the treatment of his slaves, James told his attorney that he would ‘rather suffer some loss by my Manager's lenity, than be enrich'd by his severity’.Footnote 65 In 1799 he reiterated the point: ‘I had much rather suffer in my interest, than that they [enslaved people] should suffer by hard treatment, & ill usage.’Footnote 66 But more frequently, and especially in the years immediately before Williamson's letter, James worried about ‘heavy outgoings’ and emphasised the need to ‘strain every nerve to make’ a larger crop.Footnote 67 In one of his first letters to William Rhodes James as attorney, Haughton complained about the estate's expenses and emphasised that William should ‘drop all thoughts of any fresh purchases’ of enslaved people.Footnote 68 This decision suggests a lack of concern for the intensity of work that those already on the estate had to do, effectively consigning them to working increasingly hard as the number of available workers decreased.Footnote 69 James's repeated complaints about the size of the crop and the lack of labour to produce it suggest the structural reasons that underlay Kirkaldy's ‘severity’.

By the time Mary Williamson wrote to Haughton James, the enslaved people of Haughton Tower had sought their own way of challenging the new severe regime. As Williamson explained, they tried to influence the situation by seeking the intercession of another of Haughton's cousins, John H[aughton] James, who had recently arrived in Jamaica. A letter from John confirms Mary's account. He wrote that ‘during my stay at Green Island about three weeks since’ (that is, in mid-August 1809), ‘a vast number of Negroes from your Estate came to complain of the ill treatment which they received from your overseer and head Negro driver and requested me to speak to Mr Brown upon the subject’. John James reported that he had tried to speak to Brown, but had been met with ‘violent rage’. Brown accused him of unwarranted interference in the ‘management of Haughton Tower Estate’.Footnote 70

In approaching John James, the people of Haughton Tower adopted a common tactic. When managers attempted to worsen conditions on New World plantations, enslaved people frequently responded by complaining to another authority figure.Footnote 71 Enslaved people often tried to work the complexity of the ownership and management of Caribbean plantations to their advantage. The management of large Caribbean estates took place through multiple layers of authority: from the enslaved drivers, to the bookkeeper and overseers who lived on the estate, to the attorneys and relatives who lived elsewhere in the colony, to, in many cases, the absentee plantation owner, in the metropolis. Enslaved people's tactics of playing one authority off against another could lead to the removal of individual overseers and reversion to earlier labour norms. But in this case, the Haughton Tower estate people's application to John James backfired. Brown angrily rejected John James's attempted intervention and then retaliated against those who had complained. For reasons unexplained in the documents, Brown and Kirkaldy perceived Williamson as a leader in this struggle. They destroyed her garden and provision grounds, and pulled down not only her house but also the one that she had built for her sisters.

Williamson drew on legal language in her letter of protest – ‘Honoured Sir this is the truth and nothing but the truth’ – and framed her concerns within a language of rights. This point in the letter is the only one where her syntax and punctuation breaks down, perhaps suggesting the intensity of Williamson's anger at the turn of events: ‘Now Honoured Sir as I was sold of the property free I mought have been disc[ou]raged, as having no property or wright what has my two Sisters and there young children no wright to a house on their Masters Estate, their children are young and left without a shelter.’ Williamson's anger at Kirkaldy and Brown's rejection of the obligations of their slaveholding recalls Emilia Viotti da Costa's study of the Demerara slave rebellion of 1823, which argues that ‘while masters dreamt of total power and blind obedience, slaves perceived slavery as a system of reciprocal obligations’.Footnote 72 It was the breach of these obligations that outraged not only enslaved people but also those, like Williamson, who retained connections with them, despite freedom.

Mary Williamson did not claim to have led or even participated in the slaves’ delegation to John James. Perhaps this was because she was writing to complain about damage to her and her sisters’ houses and therefore did not want to mention behaviour that James might perceive as justifying Brown and Kirkaldy's attack. But neither did John James mention her. Most likely, Williamson was not prominently involved in the protest, but Brown and Kirkaldy resented her because she was a free person on the estate who was not under their control. Thomas James had allowed her to establish herself as a free woman of colour outside the normal plantation hierarchy – something which, like the abolition of the slave trade, damaged their sense of authority. Their destruction of Williamson's and her sisters’ property was probably opportunistic and retributive, taking advantage of a broader dispute to attack someone they had resented for some time.

Indeed, the crux of Williamson's request was to move beyond her dependence on the fluctuating will of the local managers by gaining land of her own. In this she expressed the perennial desire of enslaved and freed people throughout the Americas: for secure access to land.Footnote 73 She asked James to provide her with ‘a little spot somewhere on the Estate’, again stressing the importance of her relationship with her sisters: ‘I do not wish to go from my family, as they want every assistance I can give them.’ But perhaps equally important was the support that they gave to her. If she did not get the land, she would be ‘obliged’ to leave, she says. Where would she have gone, and what would she have done?

In framing her letter, Mary appealed to Haughton's self-interest: his estate was being so badly mismanaged, she concluded, that if he did not intervene to reduce the severity ‘soon … you will have no slaves’. But she also invoked Haughton's familial relationships, half apologising for ‘complain[ing] to an Uncle against his nephew’. Williamson's letter acknowledged and tried to use the fact that both slave-owners and enslaved people were deeply enmeshed in family ties extending beyond the conjugal, sexual and parent–child. But these family ties worked to different purposes. James's kinship network allowed him to run his plantation. Williamson's enabled her to mitigate her family members’ suffering under slavery.

Mary Williamson's letter affords us a rare glimpse into one formerly enslaved woman's life and the lives of those to whom she was connected. We can learn a great deal from its densely packed five hundred and some words, especially when contextualised with other letters to and from members of the James family. Nevertheless, in reading it we are continually brought up against the limits of what it reveals. It is not as frustratingly sparse as the snippets of information in runaway advertisements or wills out of which scholars like Marisa Fuentes have constructed counter-archival histories.Footnote 74 Indeed, the letter seems to challenge Fuentes's pessimism about the possibility of finding the words of enslaved and freed women in the archives of slavery. Still, it remains a fragment, a single sheet of paper from which we may try to rebuild a world. It points to the limits of what even such a powerful source can tell us. Many basic empirical questions remain unanswerable: What was James Tumming's connection to the James family? Did Mary Williamson have children, and if so what happened to them? How old was she when she wrote to Haughton James? How long did each of the phases of her life last: as an enslaved woman; as a woman living in an unstable legal limbo as the sexual partner of the man who (perhaps) had promised to pay for her freedom; as a ‘well situated’ free woman in Trelawny after Tumming's death; and as a free woman living back on the estate of her likely birth? Even more challenging are more subjective questions such as: what were Mary Williamson's emotions towards James Tumming and his to her? Why did Thomas James want her to return to Haughton Tower? What was Mary's relationship with others enslaved on the estate, besides her sisters and their children? How did her sisters understand what was happening?

Such absences are the routine stuff of historical research, perhaps especially in the study of slavery. Saidiya Hartman poses the question, ‘How can narrative embody life in words and at the same time respect what we cannot know?’ She urges us to resist the temptation to try to ‘give voice to the slave’, instead allowing ourselves to ‘imagine what cannot be verified’.Footnote 75 In an article that responds to Hartman's work, Stephanie Smallwood calls for a history that is accountable to the enslaved.Footnote 76 I have approached Mary Williamson's letter with these injunctions in mind.

The letter sits aslant, though, to recent scholarly discussions about the nature of archives and ‘the archive’ (often considered as abstract, singular, metaphorical). Michel-Rolph Trouillot emphasised that ‘archives assemble’ and ‘help select the stories that matter’; Carolyn Steedman writes that, while archives are full of mountains of paper, and historians always anxious about the impossibility of reading everything we want or need within them, ‘there isn't, in fact, very much there’.Footnote 77 Arlette Farge suggests that historians need to be conscious both of absences and of our own practices of selection in the context of overwhelming quantities of archival paper.Footnote 78 Yet these important discussions of archival exclusions rarely consider those traces of the past, like Mary Williamson's letter, that are preserved, but outside of any institutional archive, with no official record of their existence. Ann Laura Stoler's attention to ‘archiving-as-process rather than archives-as-things’ helps to make visible the series of chance events that enable me to raise unanswerable questions about Mary Williamson's letter.Footnote 79 Had Tabitha James not become interested in the material in her family's attic, and had she not contacted me (or someone like me), we would not have access to it at all. Yet the preservation of Williamson's letter among a series of other materials produced by and for Haughton James and his descendants powerfully conditions the ways in which we can read it. How might the letter be read if it was preserved alongside the narratives and memories of others who had been enslaved at Haughton Tower estate?

There must be other private collections containing letters like Mary Williamson's, but historians will not have access to them unless their owners realise they are there, and make it possible for others to read them.Footnote 80 Privately held papers are at greater risk of damage or loss through lack of preservation than are archival collections. For scholars, it also means that permission to access and quote from them is dependent on the goodwill of the owners. I am grateful to the James family for allowing me extended access to the collection, and for granting permission to quote from it. But even in the light of this, it would be remiss not to draw attention to the fact that one of the legacies of British slave-ownership – to use the phrase coined by the important University College London project – is that this cultural, archival patrimony is owned by relatives of Haughton James, not of Mary Williamson. In today's world of increased public and institutional interest in slavery and in the voices of enslaved people, the uncomfortable truth is that the collection has a potential sale price that is raised by the presence of Williamson's letter. Also uncomfortable is the fact that I have benefited from this maldistribution of the legacies of slave-ownership: I, as a white historian based in Edinburgh, rather than one of my colleagues based in Kingston, was invited to read them. In this article I publish the full text of Mary Williamson's letter, alongside my effort to contextualise it based on further primary evidence and broader scholarship and to ‘imagine what cannot be verified’. I do so to ensure that Mary Williamson's words are known, and to enable others to work with them, in the hope that doing so shifts, at least partially, the balance of this maldistribution.

Finally: how does the story end? There is no definitive answer – and of course, stories like this do not really end. I would love to have found a letter from Haughton James in which he agreed that Mary Williamson should have a plot of land on Haughton Tower estate in perpetuity. I would love to imagine a future in which Williamson supported her sisters and their children, and they her, perhaps even living to see her whole family's emancipation in the 1830s. But these are fantasies, deriving from what Smallwood describes as historians’, our readers’ and students’ ‘yearning for romance, our desire to hear the subaltern speak, … our search for the subaltern as heroic actor whose agency triumphs over the forces of oppression’.Footnote 81 Although the collection includes Haughton James's copies of many outgoing letters, there is no letter to Williamson, or even one that mentions her. Most likely, he did not respond.

Yet there is a possible clue to Mary Williamson's later life. In 1817, when the colonial government required all slaveholders to register the people over whom they claimed ownership, a Mary Tuming [sic] Williamson of Hanover registered Nelly, a twenty-five-year-old African woman, as her slave.Footnote 82 Might this be the same Mary Williamson, who had by this time added Tumming's name to hers, in slightly modified form? By 1820 the same woman, now named as Mary T. Williamson, had acquired two more enslaved women, and by 1823 she had freed one of them, Margaret Williamson, whom the registration documents identify as ‘sambo’.Footnote 83 Perhaps Margaret was one of Mary's sisters, whom she purchased and then freed.

Or perhaps not. The Mary T. Williamson who freed Margaret signed the document with her ‘mark’ (an X, routinely used by illiterate people to sign official documents), while Mary Williamson's letter to Haughton James closes with her signature. The similar names may be mere coincidence, the similarity an enticing mirage, part of the seductive fantasy critiqued by Smallwood and others. The uncertainty underscores the challenges of biographical writing about enslaved and freed women who make such fleeting appearances in the archives. The fragmentary archival trace of Mary Williamson's letter to Haughton James can prompt us to revisit a lot of what we know about slavery, especially the significance of sisterhood and siblinghood for enslaved and freed people. It can lead us to confront the possibly ironic consequences for enslaved people in the Caribbean of the 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. It cannot, though, fill the absences at the heart of our knowledge of the experience of slavery.