In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the distinction between the urban and the rural environment was less clear cut than it is today. Green spaces and vegetable gardens covered considerable expanses intra muros, and animals abounded, evolving in close proximity to humans and in symbiosis with the surrounding countryside. Urban society was indeed largely dependent on animals, their work, their strength, their flesh and their energy to meet various needs, ranging from transport to food.Footnote 1 Since the 1980s, the ‘animal turn’ has seen a proliferation of studies, with historians focusing on fauna as a means of studying both human society and urban history.Footnote 2 Animals, it is now recognized, have contributed to the creation of towns, and have had an impact on their materiality, management and development.Footnote 3 Exploring how they have shaped towns, guided urban planning and responded to major developments in society is therefore a legitimate objective, one that gives us a perspective of them as living beings, which, in spite of themselves, have played a leading role in this environment.

Of all the animals living alongside urban dwellers in the early modern period, the horse is undoubtedly the one twenty-first-century men and women most associate with towns and cities of the past. Providing transportation for people and goods before the invention of the internal-combustion engine, horses, carriages and wagons increased street traffic in nineteenth-century towns in Europe and North America.Footnote 4 Their omnipresence in written and iconographic sources, as well as in recent studies on equids,Footnote 5 attest to their absolute necessity to daily life during the ancien régime, and hence the considerable role they played in economic development and in preserving social relations. The theme of transport in urban history has attracted considerable attention in the last few years, particularly in view of trends in the international historiography of technology, as attested at the SHOT meeting (Society for the History of Technology) held in Atlanta in 2003 and the T2M conferences (Traffic, Transport and Mobility) (Eindhoven, 2003; Dearborn, 2004).Footnote 6 The role and importance of the horse as engine have also been addressed by Daniel Roche in France, Clay McShane and Joel Tarr in the United States and Peter Edwards and Thomas Almeroth-Williams in the United Kingdom.Footnote 7 In City of Beasts, Almeroth-Williams examines how animals shaped Georgian London and agrees with Ann Norton Greene's observations concerning the continuing fundamental role of work horses in the nineteenth century, despite the industrial revolution and the use of machines.Footnote 8 Greene also highlights the key social and political imperatives behind the gradual phasing out of horses in cities, an observation that is also underlined by Andrew A. Robichaud in Animal City. The Domestication of America. Footnote 9 The historiography of the modern period, on the other hand, emphasizes the noise and polluting odour caused by animals and horses in the city, as well as the impact of equids on the organization of the urban space, such as traffic jams and accidents and the ensuing police regulations.Footnote 10 The approach is generally anthropological – with a focus on human representations, decisions and facts – rather than ethological. Animal studies have steered away from the latter perspective over the past 40 years, in an attempt to restore focus on animals in investigations of anthrozoological relations, in an interdisciplinary perspective.Footnote 11 Although some historians, including Éric Baratay and Chris Pearson,Footnote 12 take this route, this article does not pursue the fashionable ‘animalist turn’, nor does it address the issue of animal ‘agency’. The objective is not to consider history from the point of view of animals; however, this does not mean considering them as merely passive actors, but rather looking at their true influence and roles.

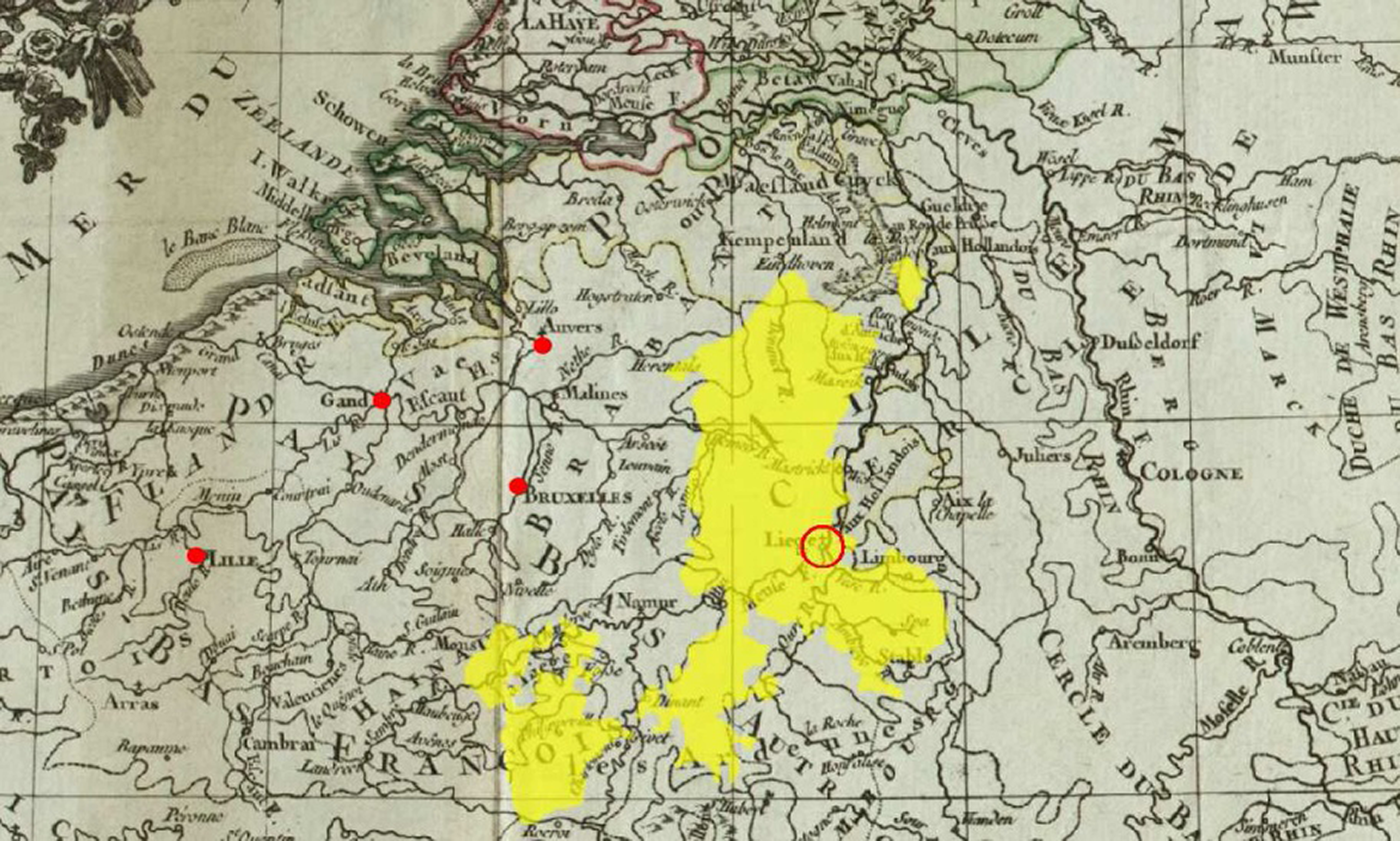

In spite of the increasing volume of literature relating to horses in the city, there are not yet any studies that focus upon how Belgian cities dealt with horse-drawn traffic in the early modern period. This article fills that gap by specifying how traffic was managed and by shedding light on the urban environment and how it was ordered in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of the Principality of Liège in the eighteenth century, indicating the locations of Liège and Namur – the two cities of most interest here – as well as a few large towns in the vicinity.

Source: L.-C. Desnos, General Civil and Ecclesiastical Atlas. The French, Austrian and Dutch Netherlands, Divided into Civil and Ecclesiastical Provinces (Paris, 1766). Image retouched by I. Gilles, ‘Les demeures patriciennes et leur organisation intérieure à Liège au XVIIIe siècle. L'influence du modèle français’, University of Liège Ph.D. thesis, 2012, 23.

Horses and vehicles may be taken to represent the impact of animals on the way the city was built. They are among the key figures in the planning process, a challenge to ‘the road network's ability to manage traffic, limit problems, and authorize the parking required for trade’.Footnote 13 This also means paying attention to chronology and studying the evolution of the phenomenon in the urban environment: when did the vehicularization of cities take on exponential momentum? Hence, it is through this vital means of transport that we begin to see the organization of the urban community – and its actors – taking shape.Footnote 14

Located in the heart of Europe and having the continent's densest urban make-up in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the territory of present-day Belgium was a combination of two quite distinct socio-political realities: on the one hand, we find the Netherlands, administered by a sovereign issuing from the Spanish House of Habsburg and later, after the Treaties of Utrecht (1713), by the Austrian branch. Brussels was the capital. On the other hand, in the east, we find the Principality of Liège, an autonomous region led by a prince-bishop, albeit a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire since the tenth century. Dependent on the great European powers and close to France, these two states included a dense network of cities mostly vying for position, which had nowhere near the demographic numbers of major European cities, but which, for that very reason, are representative of urbanism in the early modern period.Footnote 15 Studies often focus on remarkable agglomerations like London or Paris, extremely large and densely populated capitals that were not necessarily representative of the urban reality of the period. Most agglomerations were more modest and are worthy of investigation. In doing so, it is interesting to look at several elements of comparison, particularly relating to urban planning and governance. For example, were the paths taken by small and medium-sized cities and the urban planning measures they adopted similar to those of the European behemoths? Was there a perceptible difference in the rate at which these measures were implemented? Does research on Belgian cities confirm the impression given by Emily Cockayne in Hubbub that English cities in early modern times were particularly chaotic and unregulated?

Furthermore, towns in the southernmost Netherlands and the Principality of Liège have rich archives that are of great assistance in the study of human–non-human animal relations. The cities of Liège and Namur will be the main focus of this study. They were chosen for the different political and demographic advantages they present, as well as the complementary nature of their documentation. The regulations of authorities, the townspeople's requests, police reports listing infringements, judicial enquiries and newspapers are utilized here alongside iconographic and material evidence. Pursuing this trans-documentary approach in which different types of sources are compared, we also propose a methodological process in which anthrozoological relationships are examined.

Traffic: dense, complicated and ever on the increase

On 6 July 1776, François Laderière, a middle-class Namur fish merchant, saw a wagon on the corner of the bridge over the Sambre bounding at great speed towards Rue Saint Hilaire, right in the city centre. It was not travelling in the middle of the road, but near the edge. The vehicle struck a horse laden with a bag of flour, despite the cries and attempts of the owner's son to prevent the collision.Footnote 16 Flour flew everywhere, the driver took flight and the horse, whose leg was broken by the wagon wheel, lay stricken on the public road.

That the city was regarded as ‘a hell for horses’ is a fact: the urban environment exhausted them, wounded them and subjected them to endless changes in speed and the often slippery surface slowed them down.Footnote 17 However, the questions raised by the event witnessed by François Laderière in the summer of 1776 also pose a challenge to the policing of urban traffic in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Were such accidents frequent? Did a highway code exist? Drawn from a judicial enquiry, this example illustrates the extent to which urban layout, driving rules and city planning strategies were needed to ensure the daily flow of traffic while preventing accidents.

City traffic in the early modern period was largely characterized by its density. This was mainly a result of the major economic and commercial role played by large towns, where agricultural and industrial goods were traded in indoor and outdoor markets and workshops, thus leading to a heavy flow of traffic. Furthermore, from the Renaissance to the turn of the twentieth century, the number of equids increased considerably throughout Europe, as a result of a rise in energy needs before the success of railways.Footnote 18 This factor goes hand in hand with the development of transportation routes on land and by river, seen in the Netherlands in the eighteenth century.Footnote 19 In addition to draught horses and wagons, we might also point to the carriages and riding horses used by the social and ecclesiastical elite for travel and, more especially, to demonstrate their social standing.Footnote 20 Stagecoaches also enabled town dwellers to travel from one city to another. Thus, a coach would leave Brussels bound for Paris twice a week, stopping at Mons and Valenciennes, for a total journey time of 30 hours.Footnote 21 Saddle horses and vehicles were also available for hire.Footnote 22 Indeed, there were numerous vehicles in towns, as attested in the reports of the governor general of the Netherlands, Charles de Lorraine.Footnote 23 They became even more diverse in the seventeenth century, and especially in the eighteenth century, when berlins and berlin coupés, trucks, vis-à-vis, cabriolets, barouches and wursts plied the roads day and night.Footnote 24 As these vehicles became more diversified, they also increased in number. Referring to repairs on a quay in Liège in 1662, the author of the Sommaire historial de Liège stated that the work was done in order to enable coaches to travel on it, ‘which at that time were coming into vogue among the rich and people of means’.Footnote 25 Indeed, the seventeenth century saw the rise of the fashion for carriages in the Mosan city. In June 1660, another chronicler pointed out that before, ‘there were but two carriages in Liège, whereas now they are found by the hundred’.Footnote 26 These numbers are clearly to be treated with caution, especially since one contemporary wrote on the subject in 1709: ‘Sixty years back, there were no more than a half dozen; and they were only built of leather; we now see more than sixty for which as many valets, coachmen and other servants are needed.’Footnote 27 While the authors do not agree on the number of vehicles present in the city in the late seventeenth century, they both underline an increase that seemed considerable to them.

This development, alongside the proliferation and increased sophistication of horse-drawn vehicles, advanced even further in the next century, once cutting-edge French coachwork had become notable right across Europe, helping to increase trade with Paris.Footnote 28 In addition to the French capital and London, Brussels became another important manufacturing centre for carriages,Footnote 29 and went on to achieve international renown in the field. Hence, production was on a considerable upswing by the end of the ancien régime, and the issue of mobility became more pressing than ever.Footnote 30 Through its geographical proximity to France and the presence of a very famous carriage works in the territory, the cities of the Netherlands and the Principality of Liège followed the same general process of the ‘vehicularization’ of space as other major European cities of the time.Footnote 31 In Paris and London, the dizzying expansion of transport linked to trade and entertainment in the eighteenth century accentuated the problem and posed similar issues, although on a different scale altogether. By comparison, Brussels counted 180 horse-drawn carriages in 1802. The number of carriages in Paris rose from around 300 in the mid-seventeenth century to 15,000 by 1750 and had reached 20,000 by 1765. Although less impressive, in London the increase was nonetheless considerable.Footnote 32

From then on, traffic density and difficulties were attributed to the urban layout and lifestyles of the early modern period. Stuck within its ramparts, the city was a concentrated environment lacking space.Footnote 33 Medieval walls imposed a significant limit on urban leaders and improvers that should not be overlooked. Although some of Liège's ramparts collapsed at the end of the eighteenth century, it was not until the nineteenth century that they eventually disappeared as a result of private construction. The situation in Namur was similar: although demolition of fortifications began in 1784, the city would not be rid of them for another century.Footnote 34 Unlike larger cities like London and Paris, whose walls and old city gates were demolished in the mid-eighteenth century or earlier,Footnote 35 Belgian cities were trapped within their walls for the entire duration of the ancien régime, which limited opportunities for development. The winding narrow arteries inherited from the Middle Ages, where numerous obstacles sprouted from the densely built-up urban fabric and professional activities proliferated, did not facilitate movement.Footnote 36 Thus, in Verviers, one inhabitant of Rue de Heusy said he was unable to get his horses out of his courtyard to take them to water, because of obstacles on the public road.Footnote 37 The narrow lanes, the abundance of manure, the absence of demarcation between the spaces used by vehicles and pedestrians, the stalls and shop fronts, the protruding constructions and cellar hatches in the ground were all totally incompatible with horse and carriage traffic. Streets were not built for this purpose, hence the mobility issues, as illustrated in a painting depicting Meir in Antwerp (Figure 2).

Figure 2. La place du Meir à Anvers, 1601–1700, oil painting, 90 x 140 cm, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels (Institut royal du Patrimoine artistique – IRPA).

Vehicles particularly ‘highlight the extent to which the morphology of urban space inherited from medieval times was unsuited to such traffic’.Footnote 38 In Rue des Bouchers in Namur, monks residing at the Floreffe convent testified to this state of affairs and lamented the daily complexity involved in moving up and down the street. It was so narrow that it was impossible for two wagons to pass each other. One had ‘to back up into the houses’ to allow the other to go by. Not to mention the fact that the same street was often inaccessible because of the ‘stench of animals’ or flooding from the river:

Remonstrance from the Monks and Abbot of the Convent of Floreffe that their house of refuge which they hold and possess in Namur is located in an extremely inconvenient place, that is, Rue des Bouchers; being only 9 and a half feet wide, when there is an oncoming wagon, one of them is forced to withdraw into the houses, because there is only room for one wagon; the street is always filled with rubbish and filth caused by the continual and daily slaughtering of animals, such that it is practically uninhabitable.Footnote 39

Likewise, the inhabitants of the centre of Liège also expressed their dissatisfaction with the narrowness of the roads, where ‘city wagons…have a hard time getting through’.Footnote 40 Such testimonies are explicit about the city's difficulties in dealing with the situation, opening the way to questions regarding accidents that might occur and traffic rules.

Bad-tempered coachmen, reckless drivers and child-killing carters: road hazards and their originators

Although it can be assumed that accidents were becoming more frequent with the growing number of horse-drawn vehicles, they were still relatively few, according to the sources consulted, and fatal cases were rare. In Lille, there were 45 traffic deaths between 1713 and 1791, accounting for 6 per cent of all accidental deaths in the city.Footnote 41 Across almost the entire eighteenth century, a total of 12 people met their deaths for similar reasons in Douai.Footnote 42 In Namur, the sergeants reported at least six injuries, while a few Provincial Council investigations also reported on disastrous ends. Although these accidents were few in number and were part of the general events of urban life, the danger was very real and was perceived as such by residents, who grew accustomed to shielding themselves from it. In a context where the population moved about on streets with no pavements, and thus with no clear separation between the space for vehicles and the space for pedestrians, the latter were often forced to stand back to let carriages go by, sometimes at the very last moment.Footnote 43 It should be noted that carriages could go as fast as they wanted, which increased the risk of collisions with people on foot as well as with other vehicles, as observed earlier.Footnote 44

Among the individuals targeted by the authorities because of their non-compliant behaviour on the road, merchants, young people and above all coachmen – those who drove horse-drawn carriages – were singled out in particular. The image of the bad-tempered, aggressive coachman is a commonplace that was spread through iconography and literature alike.Footnote 45 For example, Louis-Sebastien Mercier and horse veterinarian Guillaume-Etienne Lafosse described the martyrdom of animals and pedestrians in Enlightenment Paris.Footnote 46 The situation was similar in the city of Liège, where the attitude of coachmen and the difficulties in getting around were described by a traveller from Paris to Spa: ‘All the streets leading to the palace are dirty, narrow and unsafe for a man on foot. Coachmen, who by nature are hard and insensitive, are that much worse here: they make sport of forcing you back against a wall.’Footnote 47 Johann Georg Bergmüller (1688–1762) was someone who seemingly tried to escape from in front of a carriage near Saint Lambert Cathedral (Figure 3), whereas the poet Guérineau de Saint Péravi described his walk through the streets of Liège as follows:

Figure 3. Johann Georg Bergmüller, View of the Large Church of Saint Lambert, in Liège [n.d.], Liège, Cabinet des Estampes, inv. 377.

Inconveniences and road accidents could also be caused by merchants and anyone else using carts or wagons in their occupation. In addition to the testimony of François Laderière referred to above, another good example is found in the investigation by the Provincial Council of Namur concerning a miller named Martin Motte.Footnote 49 This individual worked for the Sambre mill in Namur and was charged with murder after a four-year-old boy was crushed to death beneath the wheel of his wagon as he was returning to his place of work.Footnote 50 On another occasion, the same miller was at the market with his vehicle loaded with grain. Unable to move easily because of the density of the crowd, he ran into a pillar. The pillar fell on a twelve-year-old child who, unable to get out of the way fast enough, was crushed and perished. Martin Motte pleaded not guilty, especially since, in the first case, the young victim had shot out from the left side of the wagon, so the driver was unable to see him. He wrote to Philippe V requesting a letter of remission and won his case.Footnote 51 As noted above, these accidents were probably relatively unusual, but the layout of buildings coupled with the concentration of population made the risk very real.

While coachmen were widely criticized and drivers in general could cause damage, it should be stressed that their task was far from simple. They had to manoeuvre in narrow, winding, densely populated streets, encountering difficulties related to the weight of their vehicles and their ease of handling. More difficult to drive, carriages without tillers were prohibited in Liège and in towns along the Franco-Belgian border.Footnote 52 Another complexity was the unforeseeable reactions of animals who were hard to control and were easily frightened: ‘Horse-drawn transport remains an unruly engine, always highly temperamental.’Footnote 53 Vulnerable on unsteady ground and subject to injuries, horses are living creatures that can experience fear and can be frightened by noise, a sudden event or contact with other animals, such as dogs.Footnote 54 Such an incident happened in December 1775, when the Netherlands Gazette reported that a saddler's horse pulling a light cabriolet in the city of Brussels, suddenly kicked several times and ended up careening off at full gallop.Footnote 55 Ideally, drivers were expected to be able to lead the animal, that is, to control it, communicate through language and have the manual dexterity to handle the reins correctly. Yet it was technically impossible to deal with unforeseen situations requiring the horse to stop abruptly, as sudden braking was not possible.Footnote 56 Despite the coachman's cries of ‘Look out! Get back!’, it was sometimes hard for city dwellers to get out of the way in time. The coachman's skills were, however, paramount for mitigating such difficulties as far as possible, as horses driven by an inexperienced coachman were more likely to cause injury. Classified advertisements published in newspapers to recruit a coachman might state that he should have a good licence and mention the number of horses he should be capable of handling.Footnote 57

Another danger was imprudent individuals galloping their horses in town. Catherine Denys records 45 speeders in the reports of the Namur sergeants between 1761 and 1778, two-thirds of whom were young men (31 individuals).Footnote 58 Some even organized races through the city, as two people did in 1771, from the Benedictines to Rue Saint Jacques.Footnote 59 Such behaviour led to accidents on several occasions. On 9 March 1765, a sergeant reported seeing an innkeeper on horseback knock down an old woman and two children,Footnote 60 while in June 1770, another man was mown down.Footnote 61 This was not new. Previously, in August 1602, a boy rushing to the butter market on his horse, missed his turn and ended up in the street leading to the grain exchange, leaving one child with a serious head injury.Footnote 62 Thus, casualties were primarily found among the young and the elderly, who were less vigilant and had slower reflexes to get out of the way.Footnote 63 Children run without paying attention to their surroundings, which explains the plethora of ordinances prohibiting them from playing and fighting in the street.Footnote 64

A highway code?

The absence of general rules of conduct and a highway code laid down by the authorities is one of the fundamental causes of the problems mentioned above. While much was written on how to ride a horse, there was very little focus on how to drive a carriage.Footnote 65 There was, on the other hand, a set of tacit behaviours that regulated traffic in the city.

The first attitude to be adopted was driving at a reasonable speed. In town, this meant moving not much faster than at a walk. The sergeants’ reports in Namur, however, have offered up several testimonies of individuals galloping through the city on their mounts.Footnote 66 Drivers of hackney carriages, carts, wagons and other carriages also deviated from the rules; for instead of driving their animals at an ordinary pace, they made them run wildly, especially at street corners, to the extent ‘that pedestrians are constantly caught off guard and risk being crushed’.Footnote 67 The aldermen of Namur expressed their dissatisfaction on this matter and meted out a fine of five guilders, thereby establishing a sentence for speeding.

Secondly, there were methods in place aimed at co-ordinating the passage of vehicles at crossroads and junctions. One of these is reported in an accident in Namur involving two vehicles and injuring a horse at the Quatre Coins. Here are the facts: in 1765, a wagon coming from the iron gate, and thus coming down the street, went through the intersection at full speed and hit the horses of a wagon coming from Rue Saint Jacques.Footnote 68 The witnesses in the ensuing investigation said the collision had occurred even though the ‘initiator had been cracking his whip from the Carmelites through to the Quatre Coins, in such a manner that it was impossible, so to speak, not to hear the noise from Rue Saint Jacques’.Footnote 69 This detail suggests that it was use of the whip that established a priority. ‘All that whip cracking was a signal carters usually made as they arrived at street corners to avoid running into other wagons.’Footnote 70 The fact that the driver coming from Rue Saint Jacques was reproached for not having heard the racket made by the wagon coming down at a good clip also worked against him, as he was judged to have been in the wrong. Therefore, drivers had to listen carefully and judge by the noise who had right of way.

Intersections in narrow streets also required certain rules to avoid hazardous manoeuvres and obstruction of the public way. It was even more important to clarify and co-ordinate these situations, as they occurred frequently. First, the rule for driving on the right side of the road existed, but was poorly adhered to and sometimes even forgotten, which led to drivers travelling abreast of each other.Footnote 71 In the narrow streets where carriages could not get past each other, drivers ‘had to make room’ for carriages they encountered.Footnote 72 Thus, on meeting a cabriolet or a berlin, millers and brewers would have to stop, move their wagon to the side of the road at the widest point and give way. Priority was based on social rank. However, this custom was not always respected by Liège carters, ‘hence pedestrians were in constant danger of misfortune’.Footnote 73 As for the rule applying to when two coaches or wagons passed each other in small alleys, legislation was silent and drivers had to work things out as best they could, which led to chaotic situations, like those occurring in Rue des Bouchers.

Passage was often obstructed by carriages that were poorly placed or else parked right in the middle of the street. That was the case when farmers or other traders who used coal or grain stopped in the street to unload raw materials. In 1780, for example, a sergeant reported that an ass harnessed to a cart blocked the passage in front of the grain market.Footnote 74 To deal with such situations, the authorities in Liège and Namur urged drivers ‘to get as far out of the way as possible’ when a wagon, a carriage or other vehicle stopped in the street to load or unload.Footnote 75 However, there was no space ‘to move to the side’ or park. The Namur magistrates thus required millers, carters, merchants or farmers coming to the grain market with their horses to leave them in stables or ‘somewhere else’.Footnote 76 While the last suggestion is rather vague, the reference to stables – urban or military – indicates that such infrastructure was considered to be somewhat akin to today's carparks. They were available for rent and were intended to shelter the horses of residents doing business or individuals passing through town.Footnote 77 In some cities, on the other hand, there was no space expressly for parking. It was simply a matter of finding a place that did not block passage. For example, in Dinant, horses and wagons prevented the ‘comings and goings, and even access to the houses of the bourgeois’, and the aldermen simply reacted by ordering them to be placed ‘somewhere in the city’ where free passage would not be impeded, such as on bridges.Footnote 78

Given the growing number of horse-drawn vehicles, the authorities in Namur appeared to be more concerned about these issues in the eighteenth century. Parking areas were created in the busiest parts of towns and cities, such as indoor and outdoor markets, mills and at the city gates.Footnote 79 Space could also be leased along the dockyard.Footnote 80 Yet those spaces were still few and far between and horses were often left wherever people found somewhere for them, such as tied to the gates of people's homes, or church or market hall doors.Footnote 81 In Liège, carriage drivers and carters even hitched their horses to ‘window grates or in the courtyard of said town hall’, to the great displeasure of the authorities, who threatened to impound them.Footnote 82 Seen explicitly in practice as well as in the imprecise and somewhat distraught discourse of those in power, the mismatch between the urban environment and the presence of horses, to say nothing of vehicles, evidences a certain circularity here. The fact is that traffic was compromised by the lack of space and infrastructure for parking needed for travel and for trade and commerce. Thus, once again it is this question of the difficulty of adaptation of a milieu to reality in terms of mobility that was posed, not in a new way, but with more intensity.

Driving well also meant staying close to one's vehicle. However, the Liège authorities stressed that this obligation was far from being observed: ‘A good many misfortunes may yet happen, and various people may be seriously wounded, and risk being crushed, on account of millers and carters who, as they walk in the streets, get so far away from their horses and carts, that they are no longer in a position to drive them.’Footnote 83 Those individuals were thus ordered to hold onto the reins of their horses, or lead them by the tether strap as they walked through the streets of the city and the suburbs. Again, this recommendation appears not to have been particularly heeded by the mid-eighteenth century, with the privy council lamenting ‘the increasing insolence’ of some carters.Footnote 84 The horses of private individuals were subject to similar regulations and were required to be attached to prevent them wandering off.Footnote 85 However, some Namur residents left them in the market place untethered.Footnote 86 They were also occasionally observed wandering freely in the streets of Liège.Footnote 87

Renats, hurtoz and lighting: the emergence of a traffic police force

Apart from a few rules aimed at ensuring the flow of traffic, the authorities attempted to address the limitations posed by the urban layout and the road system. The seventeenth century, and to a greater extent the eighteenth century, saw the emergence of a traffic police, aimed at controlling space and, as far as possible, safeguarding the movement of goods and people. For example, Christophe Loir has shown the importance of the issue of access and traffic in the plans for a new theatre in Brussels at the end of the ancien régime.Footnote 88 More generally, this observation goes hand in hand with the development of urban policing and the requirement for safety in cities during the Enlightenment. This does not mean that the authorities’ interest in making urban space safe was newly found, but rather that this objective was reinforced by an awareness of the need to prevent accidents, and this led to the establishment of various structures aimed at guaranteeing and improving safety and traffic. Authorities took steps to widen several streets, urging owners of houses with doorsteps, signs, shop fronts and roofs protruding onto the public way to remove them, to affix gutters to dwellings and to cover cellar hatches that opened onto the street.Footnote 89 Street lighting was another element that facilitated traffic: oil lamps were installed in the streets of Namur in the 1780s. Another were the fines issued by sergeants to drivers whose carriages had no lights.Footnote 90 By the end of the eighteenth century, in this context of urban improvement, there was a desire in Liège to separate the spaces intended for pedestrians from those meant for carriages. Once the refurbishment of the quays was completed, the authorities wanted the public alleys and promenades to be reserved for pedestrians, and no longer ‘spoiled’ by horses and carriages.Footnote 91 In Namur, parking spaces were created, as mentioned above, and the city adopted rounded corners. This involved eliminating 90 degree angles on corner buildings, giving drivers better visibility and easier manoeuvring.Footnote 92 Residents placed renats (protective stone barriers) on street corners, intended to prevent carriage axles from damaging houses. They also set up hurtoz, whose form and function were similar, but which were placed on either side of carriage entrances.Footnote 93 More rarely noted were structures that limited access by horse to some roads. The privy council of Liège ordered the installation of a turnstile on the path leading to the Saint Rémy shore to prevent animals from entering.Footnote 94 Similarly, Brussels had removable posts indicating which streets were prohibited to traffic on market days, in order to protect buyers and sellers.Footnote 95 The numerous ordinances on street cleaning – a horse produces 10 to 15 kg of excrement per day – and those related to animals roaming public space can be interpreted as concern for the smooth flow of goods and people.Footnote 96 Some of these developments and the expansion of these urban development projects can be seen as part of the increasing demand for embellishment during the Enlightenment in the Netherlands and the Principality of Liège, as well as the major European cities.Footnote 97 In English cities and in Paris, for example, municipal authorities embarked on a programme of street improvement throughout the eighteenth century, which involved cleaning, widening, paving and lighting streets and encouraging the reconstruction of buildings on corners.Footnote 98 Although the changes came earlier to those cities, the responses to them were similar. In London, the first flat pavement was laid in 1782, whereas street lighting was introduced in Paris and the English capital in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.Footnote 99 Animals were an integral part of those developments and the desire to bring order to the city; in that sense, they were a profound marker of the great social and policing developments that took place in the early modern period.

Horses transporting men and goods by pack, draught or saddle were key figures in urban development and also challenged the city's ability to organize and adapt. Cities were forced to address the constant issue of traffic circulating on a poorly designed road network inherited from the medieval period and completely ill-suited to the movement of carriages and wagons. Road congestion was also frequent and driving rules were in their infancy; there was no highway code, only unwritten rules that were rudimentary, sometimes rather vague and poorly observed. The situation raised concerns, although accidents appear not to have been very frequent, or at least, little evidence remains of them. The problem posed by traffic in Belgian cities reached a critical threshold in the seventeenth century, when the number of horses and vehicles increased. The complications caused by the increasing traffic culminated in the formation, in the following century, of a police force to deal with the challenges it posed. Consequently, in the Netherlands and the Principality of Liège, urban planning measures were put into action to transform both the ‘lifestyle’ and layout of streets and to facilitate movement. These included widening roads, creating parking zones, hurtoz, renats and demarcating the separate spaces intended for pedestrians and for carriages. Yet those measures appeared later than in more densely populated cities like London and Paris. They also seem to have been insufficient, given the increase in the number of carriages and other vehicles in circulation in the eighteenth century and, above all, because urban space does not change shape or move. It continued to confine people and animals within the limits of ramparts – although their demolition began earlier, ramparts generally remained until the nineteenth century in Belgian cities.Footnote 100 Fundamentally, the presence of horses was in conflict with demographic developments and urban policing, which led to the implementation of a series of regulations. For, although the picture painted is that of a dirty environment with numerous challenges and chaotic traffic, Belgian cities followed the example of the major European metropolises of the time, and the chaos did not go unregulated, as some historians have stated.Footnote 101 Rather, we agree with Andrew A. Robichaud, who points out that leaders sought to control animals by developing broad regulatory powers.Footnote 102 Adapting to growth is always difficult in such environments; the powerlessness of governments can be seen, for example, in the lack of clarity in parking regulations. Traffic and co-existence with the ‘principal drivers of the transport system’ was therefore a challenge for authorities and required solutions that demonstrated the extent to which urban planning was mindful of the animals who lived and moved around the city.