Introduction

Since the time of the nation’s founding, Americans have grappled with the ambiguous and contradictory nature of what being American is all about. Many preeminent scholars have asserted the centrality of the American Creed in defining American identity (Toqueville Reference Tocqueville1835; Hartz Reference Hartz1955). Originally formulated by Thomas Jefferson (Reference Jefferson1951), the American Creed centers the belief in equality and the right to liberty: “all men are created equal and independent; that from that equal creation they derive in rights inherent and inalienable, among which are the preservation of life and liberty and the pursuit of happiness” (423). According to this creedal perspective, as long as you accept and abide by its tenets of equality, individualism, hard work, and freedom, among others, then you are American. However, the country’s 300-year history has shown that the exclusion of American identity membership along racial lines is extensive. Myrdal (Reference Myrdal, Sterner and Rose1944) referred to this contradiction as the “American Dilemma.” Though Myrdal specifically noted the interracial tension pitting American Creedal ideals against the reality of Black oppression, the American Dilemma has come to extend to various other ethno-racial identities.

The United States’ history of immigration has both codified and reflected the changing beliefs of who can be American, ranging from the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 to the two executive orders signed by President Donald Trump in 2017, curtailing travel and immigration from six majority Muslim countries. In addition to immigration policy, the United States also has a long history of excluding citizenship along racial lines: The Naturalization Act of 1790 limited citizenship to any free white person of “good character” who had been living in the United States for two years or longer. It is also worth noting that even when citizenship was no longer restricted to white individuals, American citizenship and American membership have not been synonymous. During World War II, approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated and incarcerated in concentration camps. More recently in 2020 and 2021, Stop AAPI Hate has received over 3,975 formal reports of discrimination, harassment, and hate violence directed against Asian Americans due to their perceived linkage to China, where the coronavirus was first detected (Jeung et al., Reference Jeung, Horse, Popovic and Lim2021).

In light of this (inexhaustive) history and the country’s rapidly changing demographic landscape, investigating what it means to be American is just as relevant and necessary as it was 300 years ago. Over the decades, scholars have employed a variety of attitudinal research to answer this very question. The findings of traditional survey research and Implicit Attitude Tests (IATs) paint a complex, inconclusive picture: while a majority of Americans endorse the importance of attributes identified in the American Creed, automatic, unconscious associations would suggest the importance race plays into the determination of who is an American. In addition to this apparent contradiction, these attitudinal studies share similar methodological limitations: the discrepancy between reported attitudes and real-world behavior. Acknowledging these methodological limitations, I posit an alternative approach: the complementary use of semi-structured interviewing and qualitative vignettes to investigate if and how components of American identity (as expressed in attitudinal research) factor into the interpretative framework from which individuals evaluate Americanness or foreignness, if at all.

In order to situate the substantive and methodological aims of this article, I first introduce how scholars have understood national identity, the varying academic conceptions of American identity in particular, and how these conceptions have been studied empirically. Here, I review and integrate the attitudinal research on this topic, drawing primarily from political science, sociology, and psychology. Next, I examine the limitations of these methods, and offer observations on how such methodological choices may, in fact, impede our understanding of American identity. In the following section, I introduce my argument and methodological strategy. Section three showcases the resulting empirical evidence of my research, and the fourth and final section elaborates on the implications of this article’s findings to attitudinal research and American identity scholarship as a whole.

Literature Review

Theoretical Foundations

Concepts of the nation and national identity have proved notoriously difficult to define, much less come to a consensus on. In line with Benedict Anderson (Reference Anderson1983), this article argues that the nation is an “imagined community,” defined by its common history and perceived distinctiveness and not a fixed, primordial entity. From this perspective, one’s national identity, like the nation, is a malleable, artificial construct, and thus susceptible to change and contestation. To be able to determine group members of a nation from nonmembers, there must be some “perceived distinctiveness.” Brubaker (Reference Brubaker1990) posits two approaches to make this determination: civic versus ethnic. Though contextualized using France and Germany as illustrative examples, they can be more generally defined as follows: civic conceptions of national identity are “inclusive and involve a set of beliefs that anyone can possess” (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2014). In contrast, ethnic conceptions are exclusive and set rigid boundaries on group membership to ascriptive attributes, e.g., language, religion, race. Though the ethnic tradition has been discredited in popular and political discourse, the relative importance of civic components versus ethnic components continues to dominate the discussion on American identity.

More recently, Schildkraut (Reference Schildkraut2011) and other scholars (e.g., Theiss-Morse Reference Theiss-Morse2009; Schildkraut, Reference Schildkraut2007; Wright, Citrin, and Wand, Reference Wright, Citrin and Wand2012) have based their research on Smith’s (Reference Smith1993) multiple-traditions thesis: there exist multiple, competing conceptions of American identity beyond just civic versus ethnic, including “liberalism, republicanism, and ascriptive [or ethnocultural] forms of Americanism” (550).

The set of principles related to liberalism is often referred to as the American Creed, which according to Huntington (Reference Huntington1997) includes the principles of “liberty, equality, democracy, constitutionalism, liberalism, limited government, private enterprise” (18–19) and culminates in the Declaration of Independence. It claims universal equality for every human being regardless of background and insists upon the “private as well as public pursuits of individual happiness” (Smith Reference Smith1988, 229). In contrast, ethnoculturalism dictates that membership to the American community derives from “particular cultural origins and customs – with northern European, if not English, ancestry; with Christianity [ … ] with the white race; with patriarchal familial leadership” (Smith Reference Smith1988, 234).

The emphasis of republicanism or civic republicanism, unlike the first two, is based on the importance of community and the responsibilities of group members to make a collective self-governance (Smith Reference Smith1988). It also calls upon a nation’s citizens to be informed and involved in public life (Banning 1986 quoted in Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2011). A more recent conception of American identity, not identified in Smith’s multiple-traditions thesis, is that of incorporationism, which endorses “America’s immigrant legacy and its ability to convert the challenges immigration brings into thriving strengths” (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2011, 41). This immigrant-based conception of Americanism is not a cover for ethnoculturalism; rather it celebrates the “sheer triumph [ … ] of the doctrine that the United States ought to sustain rather than diminish a great variety of distinctive cultures” (Hollinger, Reference David1995, 101).

Finally, Levy and Wright (Reference Levy and Wright2020) emphasize an important caveat in liberalism by mapping the different rules for functional assimilation versus formal assimilation: “Becoming functionally American is understood to mean learning English and working hard to become self-sufficient. Becoming formally American means obtaining official status and American citizenship as a condition of living in America and gaining equal rights” (28). Older theories of liberalism would argue that becoming formally American is becoming American. However, in practice, this is not necessarily the case and Levy and Wright acknowledge this distinction: “to most Americans, being American ‘in all the ways on paper’ is still not enough’” (32).

Attitudinal Research on American Identity: Surveys

Of existing scholarship that has attempted to define American identity, the most common approach, by far, has involved asking survey respondents to rate the importance of the various civic and ethnic components of American national identity (Citrin, Reingold and Green Reference Citrin, Reingold and Green1990; Li and Brewer Reference Li and Brewer2004; Theiss-Morse Reference Theiss-Morse2009; Wong Reference Wong2010; Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2011; Stokes Reference Stokes2017). In 1990, Citrin and colleagues investigated the importance of six factors in making someone a true American: believing in God, voting, speaking, and writing English, trying to get ahead on one’s own efforts, treating people of all races and backgrounds equally, and defending America when it is criticized. They found that the dominant conception of nationality in California incorporated both inclusive and exclusionary elements, though the civic factors, unlike the ethnocultural factors, all rated highly (1147).

In the following decades, scholars have expanded the range of factors examined, refined their survey questions, and included larger and more diverse samples (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2014). Of these, Schildkraut’s (Reference Schildkraut2011) Twenty-First Century Americanism Survey (21-CAS) has stood out by increasing the range of components studied to include civic republicanism and incorporationism, which has been previously overlooked, and including oversamples of ethnic minorities. Wright, Citrin, and Wand’s (Reference Wright, Citrin and Wand2012) analysis of the Cooperative Congressional Election Study argued that having respondents rank the importance of constitutive norms is a more effective measurement method compared to having them rate norms independently. Ultimately, regardless of the differences in sample size, composition, and questionnaire design, there is a high degree of consensus among these surveys: although speaking English is considered to be extremely important, “civic elements are widely endorsed and more likely to be seen as important elements of American identity than ascriptive ones,” regardless of ethnicity (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2014, 448).

Despite the persuasiveness suggested by consistent survey results, I outline three limitations that should be considered when assessing the validity of these findings. Firstly, with the exception of the 21-CAS (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2011), previous examinations of American identity content (Citrin, Reingold, and Green Reference Citrin, Reingold and Green1990; Frendeis and Tatalovich Reference Frendeis and Tatalovich1997; Citrin, Wong, and Duff Reference Citrin, Wong, Duff, Ashmore, Jussim and Wilder2001; Theiss-Morse Reference Theiss-Morse2009; Stokes Reference Stokes2017) have focused on either a single scale of Americanism or on the dual civic versus ethnic understandings of national identity. A majority of studies overlook components such as formal assimilation (under liberalism), civic republicanism, and incorporationism, as well as the average person’s understandings of their national identity. Most studies do not explain their selection of some components over others, or discuss how such selection may bias their results. It should not be assumed that the average American perceives their identity as academics do, or that they link these components together in a way theory would suggest. Although Schildkraut (Reference Schildkraut2007, Reference Schildkraut2011) conducted 17 focus groups in 1998 to qualify her selection of response options, it is not clear if any other researchers have made attempts to amend their questionnaires based on more recent or more representative qualitative investigation.

Secondly, a well-cited limitation of attitudinal survey research is the inconsistency between attitude and action (LaPiere Reference LaPiere2010; Schuman Reference Schuman1972) or, in this case, the abstract endorsement of the importance of American identity components and how that individual may determine who is a “true” American in the real-world. The primacy of survey research in many social scientific disciplines stems in part from its practical advantages and inferences that can be made about a much larger population. Often, however, the “measurement of attitudes by the questionnaire technique proceeds on the assumption that there is a mechanical relationship between symbolic and non-symbolic behavior” and lead to the unwarranted conclusion that the reported attitudes will reflect anticipatory behavior (LaPiere Reference LaPiere2010, 8). Theiss-Morse is also quick to caution that “just because Americans believe in the abstract values does not mean that such values make any real difference in real, concrete situations” (21). As a way to counteract such a dilemma, scholars have suggested the refinement of questions that “reflect the genuine dilemmas in life” (Schuman Reference Schuman1972, 353) or the “study of humans behaving in actual social situations” (LaPiere Reference LaPiere2010, 11).

Finally, I argue that the methodological debate plaguing racial attitudes literature is also relevant to contemporary American identity scholarship. Scholars have asked whether prejudice against Black Americans has decreased over time, or whether their public expression has simply become subtler (e.g., Harell, Soroka, and Iyengar, Reference Harell, Soroka and Iyengar2016). In other words, it is unclear whether blatant forms of racism have declined because attitudes have changed or because it has become socially unacceptable to express them. Bonilla-Silva (Reference Bonilla-Silva2015) argues that “racism changes over time” (74) and Jim Crow-era racism has shifted into colorblind racism. This new dominant racial ideology manifests in the “actions of tolerant, liberal whites and seemingly non-racial policies” (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2019, 26). Colorblindness and racial ideologies do not exist in social and cultural isolation, but are inexplicably intertwined with other social hierarchies, such as class, and of course, Americanism. Social scientists must ask to what extent survey results reflect changing attitudes to what makes an American or social desirability bias in the context of this new racism.

Attitudinal Research on American Identity: Implicit Attitude Studies (IATs)

More recent methodological advances in the study of implicit social cognition fills in some of the gaps of survey research and presents a new approach to understand the American Dilemma and the disparity between attitude and action. First developed in 1998, social psychologists have adapted the Implicit Association Test (IAT) to explore the less conscious or implicit associations shaping American attitudes, and how they may diverge from conscious beliefs or values. In a series of six experimental studies with multi-ethnic college students, Devos and Banaji (Reference Devos, Banaji and Devine2005) conclude that “to be American is to be White” (463). This is in opposition to the explicit assessments that to be American is to endorse civic values, and the consensus among past survey research.

Since then, researchers have extended previous work (Devos and Mohamed Reference Devos and Mohamed2014; Huynh, Devos and Altman Reference Huynh, Devos and Altman2015) by examining characteristics of the “true” American as understood by various ethnic groups and the relative inclusion and exclusion of ethnic groups in the American national identity. What they found largely confirms Devos and Banaji’s original finding: “at the explicit level, various lay definitions of the American identity coexist, and ideals of inclusion and equality are strongly endorsed [ … ] the picture emerging from implicit assessments reveals a more exclusionary perspective” (Devos and Mohamed Reference Devos and Mohamed2014, 749). Jacobs and Theiss-Morse (Reference Jacobs and Theiss-Morse2013) have also used IATs to test the associations between being Christian and being American, and found an implicit association among both Christians and non-Christians alike.

The significance of IAT research is two-fold: not only does it address the limitations of survey research to account for unconscious attitudes and social desirability bias, it highlights the continued relevance race and religion play in shaping how people define American identity. And similar to survey research, there is an unclear linkage between unconscious bias and real-world behavior. Given the importance of the link between IAT scores and behavior, one might expect to find extensive literature establishing the connection between implicit bias and actual behavior. However, when examining the predictive validity of such studies, several scholars (Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Jaccard, Klick, Mellers, Mitchell and Tetlock2009; Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Mitchell, Blanton, Jaccard and Tetlock2013; Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Mitchell, Blanton, Jaccard and Tetlock2015) conclude the limited ability of IATs to “predict ethnic and racial discrimination and, by implication, to explain discrimination by attributing it to unconscious biases” (Oswald et al. Reference Oswald, Mitchell, Blanton, Jaccard and Tetlock2015, 562). The failure to prove a robust relationship is attributed to a number of factors, including small-sample sizes, testing in laboratory-like, artificial situations, and the inability of researchers to obtain and therefore reanalyze published data sets.

The bulk of research on American identity over the last three decades has been conducted using survey methods and similarly structured questionnaires. The overwhelming consensus of these studies would suggest that civic components are much more widely endorsed than ascriptive ones. However, the findings from a few recent IATs present a contrasting, more exclusionary picture – that being White is equivalent to being American. Is it possible to reconcile these contradictory findings and can it tell us anything about present-day American identity? Ultimately, this contradiction prompts a necessary question that all American identity scholars should ask themselves: to what extent does choice in research method dictate result?

It is in response to this methodological dilemma that I introduce and apply an alternative approach to investigate the content of American identity. Often, social scientists and nonscientists alike conflate the following research questions: “How important are different civic and ethnic components when making someone an American?” and “Can we attribute real-world behavior to self-reported attitudes as measured by surveys or unconscious biases measured by IATs?” Answers to the former are assumed to have relevance to the latter. I do not suggest that social scientists forego these methods altogether due to their limited predictive power. I do, however, argue that this limitation be taken seriously when interrogating the findings each method paints. In contrast to survey research and IATs, I contribute an approach to deepen our understanding of how Americans think about American identity and to investigate the gray area between attitude and action. The focus of this research will not be the task of predicting actions, but tapping into “the processes of meanings and interpretations used in reaching the outcome” (Barter and Renold Reference Barter and Renold2000, 312), and how future research might incorporate these insights.

Data & Methods

In order to answer my research question, I needed to develop a methodology that could fulfil two simultaneous aims: 1) ascertain how people define and make sense of their national identity and 2) explore the interpretative framework or the “stock of knowledge” with which people draw on and apply the different national identity components in a concrete situation. After identifying and recruiting a sample of American graduate students, semi-structured interviews were used to allow participants to name, define, and contexualize their national identity (in comparison to academic understandings). Next, I constructed and employed qualitative vignettes to depict different pseudo-realistic situations to which participants could respond. But before I describe the granular details of recruitment and the development of these vignettes, the following section introduces the use of qualitative vignettes in social science in general and why it might be successfully applied to this research.

Qualitative Vignettes: Definitions & Applications

There are few studies that discuss how vignettes can be combined with qualitative research and none, as of writing, apply this technique to American identity scholarship. In an effort to prioritize transparency and simultaneously produce a resource for researchers seeking to explore this technique, the following section explicitly describes the steps and considerations taken to construct the three vignettes used in this research.

Hughes (Reference Hughes1998) describes vignettes as “stories about individuals, situations and structures” in which “participants are typically asked to respond to these stories with what they would do in a particular situation or how they think a third person would respond” (381). Similarly stated, vignettes are “concrete examples of people and their behaviors on which participants can offer comment or opinion” (Hazel Reference Hazel1995, 2). Though social researchers have employed a variety of vignette forms (e.g., written, audio, video) with different disciplinary aims, they generally fulfill three main purposes: to examine actions within a specific context, to elucidate judgements, and to assist in researching sensitive subjects (Barter and Renolds quoted in Jackson, Harrison, Swinburn, and Lawrence Reference Jackson, Harrison, Swinburn and Lawrence2015). Ultimately, the decision to apply the vignette technique was based on their recognition that values and judgements occur within context, and not isolation – a limitation of prior survey and IAT studies.

Multi-Method Approach: Qualitative Vignettes Embedded in a Semi-Structured Interview

The semi-structured interview begins with a series of open-ended questions to establish participants’ perceptions of their national identity. After, three vignettes, each of which are no longer than 300 words, were presented to the participants. The participants were then asked to interpret and evaluate the Americanness of the vignette character(s) in question, and walk through how they made this evaluation. The reasons surrounding participants’ responses were then freely explored. Placing the three vignettes at the end of the interview has three advantages: for one, it benefits from having already established a rapport with the participant and is therefore more likely to elicit richer data and two, it allows for the comparison between responses to previous, abstract questions and subsequent reactions to concrete situations (Kandemir and Budd Reference Kandemir and Budd2018). Finally, beginning with open-ended questions ensures that the participants are not primed by the academic conceptions of American identity that are alluded to in the subsequent vignettes.

I drew from Jackson et al.’s (Reference Jackson, Harrison, Swinburn and Lawrence2015) eight-step guidance and the applications of this technique in research about violence in residential homes (Barter and Renold Reference Barter and Renold2000), public health issues (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Harrison, Swinburn and Lawrence2015), and drug treatment decision-making (Jenkins et al. Reference Jenkins, Bloor, Fischer, Berney and Neale2010). Because this article is the first application of qualitative vignettes to the study of national identity, I wanted to explore the effectiveness of different content and methods of delivery. As such, each of the three vignettes provides a different context, ranging from more abstract to more concrete, in which participants can discuss American identity. The three finalized vignettes are briefly discussed below.

-

• Vignette A aimed to explore participant attitudes towards the four main conceptions of American identity (i.e. liberalism, civic republicanism, ethnoculturalism, and incorporationism) as embodied in four fictionalized accounts of university-aged women. By presenting these sub-vignettes as a “microcosms,” in Törrönen’s (Reference Törrönen2018) vocabulary, the vignettes can represent or bring forth “types of people, rituals, everyday life routines” or any topic under investigation in a sufficiently compact and enclosing way (7–8). In contrast to traditional questionnaires that would have participants respond to direct questions about the importance of liberal principles, vignettes (as microcosms) can explore the nuances of such concepts that are more grounded in the participant’s reality and are framed in comparison with the other components of interest.

-

• Vignette B was based on a non-fictionalized account of an American, Michael, living in New York City told to “go back to his country” by Caroline (the characters’ names have been altered for anonymity). Besides being a common story in American discourse, Jenkins et al. (Reference Jenkins, Bloor, Fischer, Berney and Neale2010) and other researchers have noted the advantages of non-fictionalized and highly plausible scenarios in that they are “more likely to produce rich data on how actors interpret lived experiences” (186). The final version of this vignette was revised to exclude descriptions that would explicitly identify the racial or ethnic background of the involved characters. In addition to feedback from pilot tests, Hughes and Huby (Reference Hughes and Huby2004) advocate that “imprecision in vignette scenarios can be used as an opportunity to investigate the reasons behind a participant’s response” (as cited in Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Harrison, Swinburn and Lawrence2015, 1402). Participant’s assumptions were then openly discussed and analyzed as data.

-

• Vignette C was also based on a non-fictionalized account, but this time of the U.S. Congresswoman, Ilhan Omar, whose American identity was publicly rebuked in early 2019. Unlike Michael, the character of Vignette B, who is a real, but anonymous figure, Congresswoman Omar is a public figure and a known American citizen. I wanted to see how participants would react to a situation where the civic and ethnic components of her American identity are publicly known or can be inferred.

The order in which I presented the three vignettes is also purposeful. I expected participants to feel more comfortable evaluating Americanness in situations that are more vague, and do not pose harm to any particular individual (i.e. Vignette A). The situations presented in Vignettes B and C become more fraught as participants are now asked to respond to situations in which the Americanness of specific and real individuals are contested. There are innumerable scenarios that I could have chosen, but I wanted to create a distinction in which the vignette subject’s racial, ethnic, and religious background can be guessed in one (i.e., Vignette B), but known in the other (i.e. Vignette C). In scenarios where ethnocultural attributes are not explicitly known, how do people interpret the reasons for why American identity might be questioned or contested? Finally, there is heightened sensitivity in America around being perceived as “racist.” I fully expected participants to attempt to distance themselves from Caroline or the people questioning Congresswoman Omar’s Americanness, and did not want potential social desirability bias to affect the rest of the interview.

Sampling Procedure

I conducted 10 interviews with American graduate students who were studying at the London School of Economics at the time of writing. The choice to recruit participants living in London is predicated on practical and also methodological considerations: international travel was not financially viable or strictly necessary, and face to face interviewing allows for the use of visual aids and the collection of para-data. In addition to location, my primary aim when defining the sample universe was to ensure a homogenous sample on a variety of parameters including demographic and life history commonalities (Robinson Reference Robinson2014). Given the exploratory nature of this research, I do not aim to make generalizations beyond my sample, but having a relatively homogenous sample helped to contextualize participant responses (e.g. the pattern of participants taking a critical stance of the United States is unsurprising since all participants voluntarily chose to leave the country for study).

Participants were recruited through a combination of convenience and snowball sampling strategies. All participants identified as either a Democrat or Social Democrat and most were raised in liberal, coastal states. A majority of participants are white and do not claim any religion. Of the three non-white participants, one identifies as mixed race, one as Asian, and one as white and Latina. Gender-wise, eight of the 10 participants identified as female.

I want to highlight important characteristics of this sample that I have taken into account when analyzing and presenting the data: a majority of these participants are white, Democrats, and do not claim a religion. All participants are living outside of the United States (at the time of data collection). It is clear that the sample does not represent the average U.S. population. As such, no claims are made for the generality or representativeness of this particular sample. Future studies should sample across intersecting demographic backgrounds in order to identify differences among the various American subgroups. The makeup of this study’s sample is sufficient given its exploratory aims.

At the time of interviewing, consent forms and demographic information sheets were distributed among participants. After clarifying the aims of the research, the interview was conducted following the topic guide as seen in Appendix C. Afterwards, each interview was audio-taped and transcribed verbatim to include hesitations, emphasis, speech repetitions and laughter, following Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2013) guidelines for quality transcription. All participants were given anglicized pseudonyms when quoted in this article.

Data Analysis Strategies

The goal was to reveal participants’ understandings of various components comprising American national identity and how they are utilized when evaluating Americanness in different contexts, ranging from the abstract to the concrete. To do this, 10 interview transcripts were analyzed using the sequential application of two qualitative text methodologies: directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005) and the discourse analysis approach associated with Gilbert and Mulkay (Reference Gilbert and Mulkay1984) and Potter and Wetherell (Reference Potter and Wetherell1987).

For the first stage of analysis, I developed operational definitions of the four components of American identity (liberalism, ethnoculturalism, civic republicanism, and incorporationism) as identified by Schildkraut (Reference Schildkraut2007). After reading the transcripts carefully, I highlighted all the text that appeared to describe or characterize an American, American identity, or any implicit reference to this grouping. Although it is common for scholars to use the paragraph or sentence as the unit of analysis, such groupings of texts could easily contain multiple descriptions of an American or American identity, which would violate a basic principle of content analysis: the coding of each analytical unit must be both exhaustive and mutually exclusive. All highlighted text was then coded using the predetermined categories whenever possible. For text that could not be coded into one of these categories, I developed new codes (including linguistic/verbal indicators, legal indicators, and physical indicators). Once all the transcripts had been coded, I finalized the coding scheme, which can be viewed in Appendix B. Finally, I counted the frequency of each American identity component, and compared and contrasted each component based on the context in which it was uttered – in abstract discussion, in a hypothetical ranking (Vignette A), and in concrete situations (Vignettes B and C).Footnote 1

However, findings from this approach are “limited by their inattention to the broader meanings present in the data” (Hsieh and Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005) and are unable to pick up on the variability and inconsistencies inherent to interview data. Thus, the content analysis methodology was treated as a preparatory method to determine the dominant components invoked in the interview transcripts. The advantage of applying discourse analysis, as a second, complementary approach is that it “abandons the empirically weak presupposition that people have an attitude which could be represented through mutually exclusive categories” (Wetherell, Stiven, and Potter Reference Wetherell, Stiven and Potter1987, 60) and can be used to document how participants construct, deconstruct, and organize their attitudes in diverse ways (Gilbert and Mulkay Reference Gilbert and Mulkay1984). Though the term “discourse analysis” can refer to all forms of language analysis, I will apply the discourse analytic toolkit more flexibly to look at the language surrounding the sections of text identified in the initial content analysis. I analyze various features of discourse, including turn-taking between interviewer and participant, categorization, subject positions, rhetorical strategies, and lexical fields.

In sum, the rationale for adopting this layered, multi-method approach is two-fold: direct content analysis leverages pre-existing theory to identify and define coding categories, thereby focusing and structuring the research process. The subsequent discourse analysis investigates the context in which these American identity components are invoked and possible purposes they may serve. The primary advantage of this multi-method approach is that it allows me to focus my examination on the components of interest, while still addressing “the complex content of people’s representations” (Thompson Reference Thompson1984, 69–70), whether that refers to inconsistencies or implicit meanings with regards to attitudes that cannot be captured in a summary content analysis.

One challenge of directed content analysis is that it leads the researcher to approach the data with an informed but, nevertheless, strong bias (Hsieh and Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). In order to improve coding reliability and trustworthiness, I enlisted a graduate student unfamiliar with my research aims to code an interview transcript based on my codebook. Based on their feedback, the codebook was clarified and refined.

Example of Coding Process

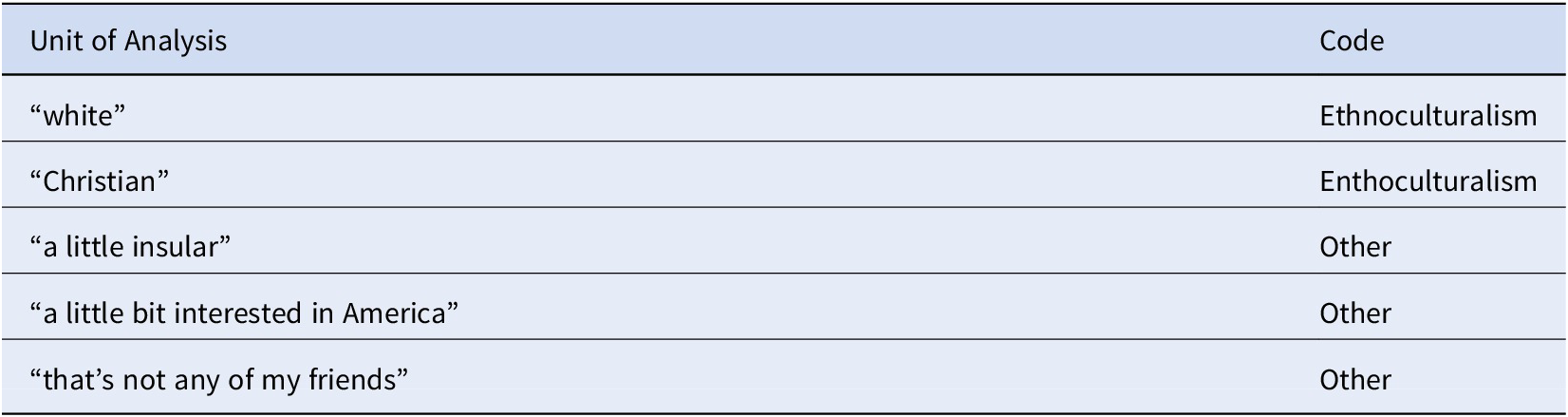

Given the amorphous process of discourse analysis, especially in this multi-method context, an example of the coding process is provided below.

Shannon: [ … ] it’s kind of stereotypical American kind of white, Christian, erm, a little insular, a little bit interested in America and American interests but, erm, obviously that’s not American that’s not any of my friends, that’s interesting to me that’s what my mind jumps to when I think of what an American is ((pause)) what really is it to be an American?

Directed Content Analysis:

Discourse Analysis:

-

• Note classification of type of American: “stereotypical American”

-

• The description provided is one Shannon does not explicitly agree with: “obviously that’s not American”

-

• Complexity in belief and automatic association: “that’s what my mind jumps to”

-

• Note confusion and uncertainty in Shannon’s response: “((pause)) what really is it to be an American?”

Overview of Results

Directed Content Analysis

After coding descriptions of American identity across the 10 interview transcripts, it became clear that a plurality of descriptions could not be coded into the four categories of liberalism, ethnoculturalism, civic republicanism, and incorporationism. As such, I went back through the transcripts and created more precise codes for all of the “other” components. Of these, the more frequently cited components included: linguistic or verbal indicators (e.g. accent, speaking English), physical indicators (e.g. clothing, occupying space), legal indicators (e.g. citizen, green-card holder), and length of residence in the U.S. The sheer number of American identity components that cannot be categorized under the civic-ethnic or four component scheme suggests that there are a number of lay definitions not addressed by recent theoretical and empirical studies.

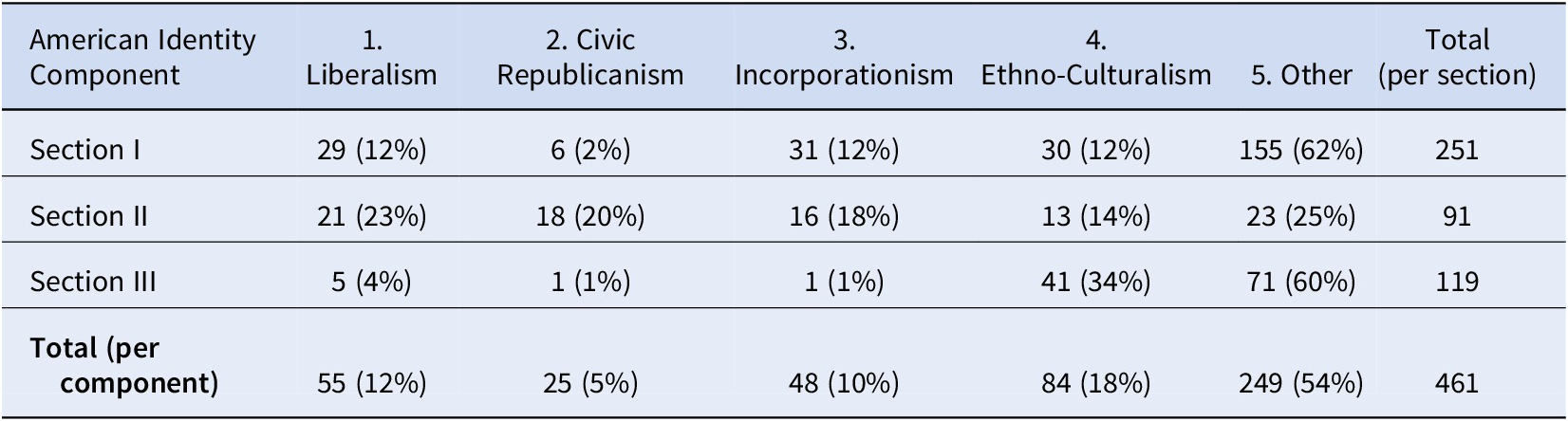

As seen in Table 1 (below), participants invoked ethnocultural components most often (18%), followed by liberalism (12%), incorporationism (10%), and civic republicanism (5%). Though the mere mention of such components has no implication and their relative importance, these numbers seem to align with the agreement in the literature: liberal and ethnocultural components are the most common ways in which to view the content of American identity.

Table 1. Frequency of Four Main Components

By calculating the frequency of codes per section,Footnote 2 I was able to compare the invocation of each type of identity component depending on the context in which it was uttered. The increased invocation of liberalism, ethnoculturalism, incorporationism, and civic republicanism in Section II is to be expected since the participants are presented with vignettes that represent each of these four components. For three of the participants, the only mention of civic republicanism occurs in the context of Vignette A, which strengthens the conclusion that civic republicanism is not particularly salient among this sample. For a majority of participants, the mention of ethnocultural components is the most frequent in Section III, when responding to a concrete situation. This is significant because it would suggest that individuals use attributes such as race/ethnicity and religion when describing or evaluating what an American is in a pseudo-realistic scenario, such as the two presented in Vignettes B and C. However, a deeper investigation would need to be conducted to elucidate its meaning.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that a majority of the codes fall into the other category, made up of linguistic/verbal, legal, and physical indicators of Americanness. This is important to take into account when considering the salience and relevance of current theoretical definitions scholars use to measure American identity.

Discourse Analysis

The results of directed content analysis provide a more focused starting point to interpret the data, but how should we interpret the numbers and what have they overlooked? The discourse analysis approach enables the researcher to examine the use of language and the broad ways in which accounts are constructed to further contextualize how participants talk about the various components of American national identity. I present the findings of this secondary analysis in two analytic sections, each addressing one of my guiding research questions: 1) what are the components of American identity and 2) what role do they play in the evaluation of who is American?

Section One: Characterizing American Identity Components

The expectation set by the literature would suggest that American identity is comprised of certain liberal, republican, incorporationist, and ethnocultural principles. However, the preliminary content analysis would suggest that a wide range of components have been overlooked, including speaking English, residing in the U.S., being loud, physical dress, relationship to capitalism, and more. Beyond their mere mention, analyzing the language used to construct these components reveals a much more complicated story.

Firstly, components of American identity are hardly ever characterized by participants as neutral attributes, despite the ways in which they are presented in survey questionnaires. Participants frequently invoke specific components in a multitude of positive and negative terms. Sally draws on her personal and communal feelings of pride when describing the incorporationist principles she sees as key to America:

there’s something really kind of cool about being able to be simultaneously an ethnic background and a national background […] in the states you can be Chinese, you can be Black, you can be Hispanic, and have that culture while simultaneously being a very proud American […] something that we (.) like most Americans that I meet kind of really cherish because something that I think America celebrates is its concept of diversity

With that said, several participants were also critical of specific attributes of American identity, including capitalistic tendencies, the loudness, the America-centrism, and the ignorance that they found as being inherent to or stereotypical of American identity. It is important not to overlook these more critical characterizations of American identity or misrepresent them. Rather than detract from American identity, they are an integral part of it. Ellie makes this explicit when characterizing President Trump: he “embodies a lot of American values because I mean American values are like ((inaudible)) I think we have some poor values as well.” Donald Trump is not considered any less American because he represents the glorification of “capitalism” or “anti-intellectualism,” he reflects this aspect of American identity. Angela, one of the participants, emphasized her personal belief “that negative feelings are just as important as positive feelings.” Echoing this sentiment, Eileen also states that “all Americans have positive and negative attributes” and that is part of the beauty of America. Sometimes, the literature cites pride and patriotism as being important to one’s American identity, but does not consider how the opposite could be just as significant.

Secondly, though some invoked components are defined by the participants’ positive or negative feelings toward them (e.g. pride for country or America-centric), participants also adopted both positive and negative talk for the same component. Take individualism, for example: the concept of the individual repeatedly emerges in reference to liberal principles, the American Dream, and the cowboy narrative. While some participants valorize individual effort and hard work in their attempts at a successful life, Scott presents a different perspective:

Erm ((long pause)) well I think we definitely favor the sort of person who does things on their own [ … ] you know the way we sort of venerate our American billionaires, it’s like these people like Bill Gates [ … ] or Mark Zuckerberg or Steve Jobs like all these people who ((pause)) you almost forget the uh ((pause)) contributions of other people and place that person above everyone else and deify them in some senses for their achievements and it leads to I guess a sense of uh they can do basically, you almost don’t even question- they become unimpeachable as people because of how we sort of venerated them

Matt echoes this more nuanced take on individualism: despite celebrating his father’s success story and individual effort as being quintessential to the American identity he also recognizes the common idolization of the individual effort, and the fact that this praise is often misplaced. He believes that “any success story is the (.) is the response of the community” and that the American identity is characterized by “a community of people who will be all going towards a similar goal erm whether or not they’re from different communities.”

Section Two: Interpretative Frameworks for Constructing American Identity

Up until this point, the motivation behind this research was the expectation that participants engage with American identity components differently depending on context – in this case, abstract context (i.e. survey studies) versus concrete context (i.e. qualitative vignettes). Through performing this discourse analysis, however, it becomes clear that the context in which participants construct ideas about American identity is not just a question of abstract or concrete, but a question of who they are in relation to other Americans. Echoing Smith’s (Reference Smith1993) multiple-traditions thesis, participants orient their discussion around a tension inherent to American identity: there exist multiple, contesting Americans at one time, depending on an individual’s background and geographical upbringing. Faced with the multiplicity of contrasting descriptions of Americans, all of the interviewed participants articulate how difficult it is to describe what or who an American is. The extracts below illustrate their dilemma:

Ellie: I don’t know how exactly I would do that because I think that there is, I think it’s erm, like I think that there are a lot of different ways to be American and there are a lot of different kinds of Americans

Angela: you have to start with all of those disclaimers, erm, and that they don’t look one particular way and they don’t sound one particular way, if you ask someone on one side of the coast they’ll say one thing and the other something else and the middle something completely different

Matt: A true American, a quintessential American. I guess there’s so many different ((pause)) I guess for me ((pause)) you know, this is a tough question ((laughs)) erm but it’s a great question […] but I guess ((pause)) there’s so many different answers for that that I have difficulty kind of putting the rest of it into words, you know

Sally: it’s hard because there are things that I want to say like quintessentially American but like, in the same vein, there’s people in the Midwest who you know completely disagree with me

Scott: So like that’s such a tough question because Americans are all so different […] so it’s hard to pick any true American because America is so ((pause)) vastly different depending on where you are in the region, you know

This dilemma is composed of three factors: one, most participants recognize the geographical diversity that characterizes the country. Two, from these diverse parts of the country emerge Americans who are different in attitude, belief, and speech. Three, selecting or describing one of these types of Americans, would inadvertently exclude or delegitimize another type of American. And this is something participants either cannot or do not want to do. Situated in, and as a response to this dilemma, participants construct American identity using three interpretative frameworks. These frameworks are constructed out of their respective repertories, “a restricted range of terms used in a specific stylistic and grammatical fashion” (Wetherell and Potter Reference Wetherell, Stiven and Potter1987, 172).

Deferral Framework: “What Would Give Me the Right to Legislate”

In the first of three frameworks, the participant is portrayed as a decision-making authority. When asked by the interviewer which previously mentioned components are important to being an American, the responses are characterized by a distinctive lexical field and the reflexive subject positioning of the participant. The following three excerpts illustrate such responses:

Angela: I mean, I don’t think I want to judge […] if I start prescribing what it means for one person to be from a place or have a connect to a place, then they get to judge me for mine and I really rather they didn’t

Sally: it’s not for me to say because I, like, being an American ((pause)) being an American has nothing to do with my personal opinion […] I will abstain because it’s not fair for me to judge their identities

Ellen: she’s an American, do you know what I mean? I’m not going to stand there and be like (.) “But are you?” Especially so, again what would give me the right to legislate that?

Note that these three participants do not say they are incapable of making a judgement, but that they will not. This denial situates the participant in a position of power and the terms with which they articulate this denial are all related, in what can be seen as a lexical field of “justice.” The words “judge,” fair,” “the right,” and “legislate” are all related in that they describe the verbs or principles that govern the law and justice it upholds. Despite having the ability or capacity to make a judgement on what being an American is, they “abstain” because it is not their place. Through this framework, the participant is able to neatly respond to the dilemma of choice (and inadvertent exclusion); rather than describe or ascribe, they defer.

Relativist Framework: “There is No One True Identity”

In the second framework, participants address the dilemma by explicitly or implicitly denying the existence of a singular, essential American identity. Some participants do so by clearly rejecting the characterization of a “true,” or “perfect” American. In the place of singularity or truth, participants describe the existence of disagreement and heterogeneity.

Eileen: I don’t know why I’m having such a hard time processing this. Basically I think part of the beauty of America is that there is no one true identity or what a perfect American can be. I think that there is room for freedom of speech and disagreement, erm (.) individual choices to live (.) your life the best way you see fit

Ellen: I don’t really believe in that. I would say like there there is no true Brit there is no true Australian there is no true South African like ((pause)) I would find that question and I do find that question very hard (.) to answer ((pause)) like it just seems very- like I’m trying to essentialize or distill what America means but (.) most countries, not American in particular obviously, are so heterogenous

In addition to these excerpts, two other participants made a similar point implicitly. When asked to rank the four university-age women from less to more American (refer to Vignette B in Appendix C), Talia provided two separate rankings: one reflecting her “individualized identity” and the other reflecting the “classic American identity.” In the former ranking system, characters Victoria (representing incorporationism) and Margaret (representing civic republicanism) represent the components of her identity that she most closely resonates with in her own life. That said, Talia states, “when I think American I would say Sarah [representing liberalism]” and ranks this component as most American in the “classic American” ranking system. Nowhere in this conversation does Talia explicitly refer to a “perfect” or “true American,” but suggests that there are multiple ways of being American, some of which are relatively more American than others depending on the criteria, but none are perfect.

Normative Framework: “What Should an American Be”

Finally, the last framework is characterized by a series of normative statements, expressing a value judgement on whether something is desirable or undesirable. In this case, such judgements are often characterized by the verb, “should,” but are also paired with the dual descriptions of being good or bad. See the following excerpt for an illustration of this framework:

Scott: They should genuinely strive for equal opportunity, should genuinely set up structures that make it so that people can come here freely and have every opportunity afforded to them that everybody else do, they should […] they should […] they should

Early on in the interview discussion, Scott repeatedly expressed how “difficult” and “tough” he found it to talk about the American decisively or in a limited set of terms. He kept couching his descriptions with long pauses and the phrase, “I guess.” But the excerpt presented above reflects a shift: from qualifiers to parallelism, from doubt to decisiveness. This participant responds to the dilemma by organizing his talk of American identity into normative statements: by expressing what the American should be like, he can sidestep the difficult, sensitive issue of having to select and therefore decide what an American is like.

Shannon and Matt operate under the same interpretative framework, extending the description from what an American should be to what’s “good” about an American. These two participants make it very clear that you do not have to be a “good” American to be an American. It is within this normative distinction that Shannon invokes the components of civic republicanism and incorporationism: “they’re not prerequisites to being American.”

Shannon: Erm, I think that these are…it’s kinda like separate questions for me, like, cause I do still feel like to be American you just need to identify as an American or to be an American citizen and what is important, what is like an American ideal, what makes like…erm what’s good about being an American, what should an American be, that’s a broader list of attributes and characteristics, like erm yeah, I think there should be this spirit of civic duty and acceptance of differences and hard work and that sort of thing but they’re not prerequisites to being an American

Matt: For me, I guess you’re an American like one, if you’re, you know ((pause)) identifies as American, then you’re an American. But for me that more identifies with the fact that whether or not I consider you a (.) good American I guess? Yeah, it considers more into- for me, whether or not you’re American it’s almost a fact, not a fact, but it’s a erm I mean in a way I think of it as like, all right you identify as American, pretty much a fact. But if you (.) it’s more about what identifies as being a good American and maybe even being a good person but like yeah so I you know I don’t equate the American identity directly with those aspects of the, you know, who they are as a person.

Ultimately, these three frameworks provided participants with the discursive resources by which they could address the sensitive and conflicting decision of identifying who is part of American group membership (and who is not). Participants utilized the three frameworks to articulate components of American identity they personally resonated or identified with, while also accounting for the numerous other kinds of Americanisms that may be in direct contestation with their own beliefs. The combination of these frameworks in this sample illustrates a very important point about the way researchers have treated American identity components up until now. Rather than a neutral checkbox, Americans invoke and interpret the same components, such as liberalism or ethnoculturalism, in vastly different ways when attempting to construct or determine what American identity means.

General Discussion

At the beginning of this article I argued that the frequent conflation between attitude and behavior in the existing literature narrows the lens with which we can understand how Americans perceive, understand, and interact with the components that make up their national identity. Results from this multi-method text analysis approach demonstrate the following four points.

First, there are a multitude of components not currently being discussed or measured. In all interviews, either a plurality or a majority of the components of American identity invoked fall outside of the main four categories of ethnoculturalism, liberalism, incorporationism, and civic republicanism. Given the small, unrepresentative sample of Americans, this does not mean that these four components are not salient, but it should call into question why survey questionnaires limit their scope to these components. Furthermore, many of the studies designing such questionnaires do not justify why they include some components to be measured and overlook others.

There are two significant components that I coded for that do not neatly fit into the current definitions of the four main categories and warrant greater discussion. The first are linguistic or verbal indicators, particularly the degree to which an individual’s spoken language aligns with standard American English. Although “speaking English” has been mentioned in existing literature and included on survey tools, little has been mentioned about the difference between speaking English, speaking English proficiently or fluently, and speaking a dialect of American English. In a survey experiment measuring immigration attitudes, Hopkins (Reference Hopkins2015) hypothesizes on the impact of non-native accented English: “modes of speaking are sometimes thought to reflect the speaker’s active choices, as listeners overestimate the malleability of accents or the ease of learning new languages” (221). There is good reason to believe that such distinctions may serve as potential markers of perceived Americanness, especially since someone could be a native English speaker and speak a non-standard American English dialect.

Another component that warrants greater discussion are legal indicators of American identity (i.e. acquisition of formal residence or citizenship) which map onto Levy and Wright’s (Reference Levy and Wright2020) definition of formal assimilation. The discussion of legal status often gets overlooked in studies of American identity without explicitly teasing out the distinction between functional assimilation and formal assimilation, even though “earnest belief and sincere emotion [has] never secured a visa” (Levy and Wright Reference Levy and Wright2020, 28). Ultimately, we cannot know how important the American accent is to American identity, compared to being white or compared to their legal status if we never include these components to be measured in the first place. It is imperative that future survey research qualitatively explore the numerous ways average Americans conceive of their own identity and incorporate those components as survey response options.

Second, the components invoked differ depending on the setting in which they are called to determine American identity. For a majority of participants, the mention of ethnocultural components is the most frequent when discussing the vignettes, representing a more pseudo-realistic setting. This is significant because it raises the possibility that survey results (reflecting an abstract endorsement of American identity components) do not necessarily translate to a more concrete setting. Instead of thinking about and bringing up the vignette character’s belief in equality for all or their identification as being American, participants frequently called upon ethnocultural attributes.

That said, there are a number of limitations with the vignettes I present (see Limitations section below), and repeated and more comprehensive investigations are necessary to corroborate and strengthen these initial findings.

Third, the ways in which components are characterized shed light on which components are indispensable to an American identity and which components signify normatively good American identity. Unlike surveys that list different American identity components as being neutral, participants both use positive and negative terms to describe being American. While participants might not think our rugged individualism or tendency to be overly loud are good traits, they are part of what makes an American an American. Similarly, there is a difference to being an American versus being a good American. As seen in participant interviews, many of the civic components that are widely endorsed in surveys (e.g. respecting America’s laws, being involved in local and national politics) are important to being a good American but are not necessarily prerequisites to being an American.

Fourth, the difficulty expressed by participants to define a singular American identity underscores the continued salience of Smith’s (Reference Smith1993) multiple traditions thesis. Many participants were either unable or unwilling to define a singular or true American identity. This difficulty stems from a number of reasons, ranging from the large, heterogeneous nature of the country or because participants believe there are a multitude of co-existing but conflicting ways to be American. As a response, participants employed various interpretative frameworks to side-step having to definitively choose the components making up American identity. Definitively choosing or ranking components, however, is exactly the exercise existing surveys ask their respondents to do. Given the experience of participants in this sample, it is worth considering the impact the cognitive load of performing this mental operation on the likelihood of satisficing for survey respondents (both past and future). Transparently documenting the results of cognitive interviewing among a diverse set of Americans could be one fruitful area of future research.

Though this article introduces a number of findings, not all of which nicely fit together, its original aim was exploratory – to apply innovative methods to a repeatedly asked question and see how participants respond. Ultimately, I intend for this research to serve as a reminder: the consistent or habitual use of certain methodologies can limit our understanding of how individuals relate to their American identity if we do not interrogate the larger implications methods have on outcomes. The main contribution of this research is methodological: attitudinal studies, as they are now, overlook the significant relationship between attitude and context and are inherently incapable of addressing the context-dependent, discursive ways individuals construct their American identity. Context is key: going forwards, how will American identity scholars inventively frame this 300-year-old question to better address the changing demographic and political landscape in the 21st century? Cross-disciplinary collaboration among researchers studying American identity, especially the methodological innovations and discussion in critical race theory, could very well produce new avenues of exploration.

Limitations

Despite their advantages, interviewing and qualitative vignettes do have their methodological and practical limitations that need to be addressed. I noted a number of ways in which bias potentially affected participant responses. Firstly, there is my positionality as an Asian-American interviewing mostly white Americans. Though most participants did not make any direct comment regarding my race, one participant implicitly differentiated our experiences as American: though she stated that her Americanness was never directly questioned she said, “I’m sure you get the question all the time, like ‘where are you actually from?’” when responding to Vignette B. It is very possible that my race may have affected other participant responses, especially when the interview pivoted to American identity as it relates to racial identity.

Secondly, there is our collective positionality as graduate school students attending a liberal university outside of the United States with a high percentage of international students. Participants would often differentiate themselves from the “Trump-supporter” or a similar such person from the “South” or “Midwest.” It is unclear whether this positioning was made based on the participants’ actual beliefs or their desire to appeal to what they thought I, and the larger university community, expected to hear.

Thirdly, several of the participants would make statements in relation to their area of study, e.g. race theory, gender studies, reception theory. The graduate-level, specific nature of the participants’ academic backgrounds means that these results are not generalizable to the wider U.S. population. This is likely linked to the more critical stance participants took when talking about America, but this criticality and awareness did not mean that participants had any less love for the U.S. or did not self-identify as an American (with the exception of one participant).

Fourth, a majority of the sample are white and do not claim a religion, which is a stark contrast to the overall American population. Whiteness and the Protestant work ethic have been central to the formation of American identity, and it is worth considering what discussions are omitted because of the sample’s makeup. I expect very different conceptions of and relationships to conceptions of American identity along racial, religious, immigrant generation status, and more.

Finally, despite refining vignette content based on the feedback of three pilot tests, gathering rich data in response to Vignettes B and C (i.e., the stories about Michael and Ilhan Omar) was hindered by practical limitations. The goal of the they-orientation in vignette development is to have the participant place themselves in the perspective of the character in question. This transition from participant to character was not seamless. When asked why Caroline may have thought or acted in a specific way, nearly every participant gave some version of “it depends.” Because many of these participants judged Caroline to be a “racist,” whether in more or less explicit terms, I hypothesize that they were reluctant to associate themselves or try to interpret the story from what they deemed to be a racist point of view.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.79.

Disclosures

None.