The fourth session of the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-4) to develop a legally binding global Plastics Treaty takes place in Ottawa, Canada, at the end of April 2024. As Inger Andersen (UNEP Executive Director) reminded us in her opening plenary remarks at INC-3:

the resolution called for an instrument that is, and I quote: “Based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastic.” Not a plastic instrument that deals with plastic pollution from recycling or waste management alone, the full life cycle and this means rethinking everything along the chain from polymer to production, from product to packaging. We need to use fewer virgin materials, less plastic and no harmful chemicals. We need to ensure that we use and reuse, and recycle resources more efficiently. And dispose safely of what is left over. This is how we protect human and ecosystem health…

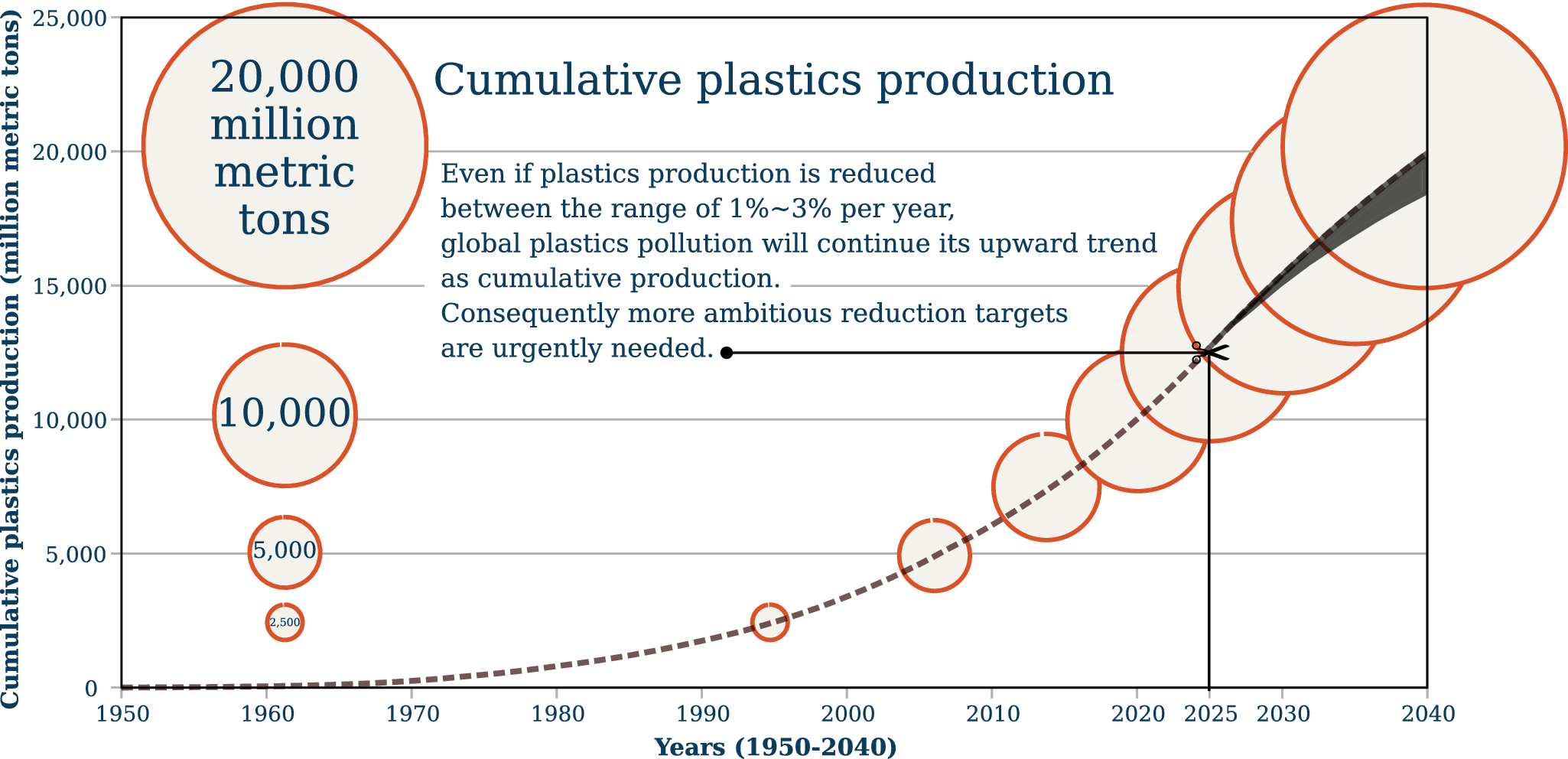

Plastics production doubled between 2000 and 2019, with 460 million tonnes produced in 2019 alone (OECD, 2022). With cumulative production reaching 10,000 million tonnes in 2020, we have a growing body of evidence about the harmful impacts of plastics on human and environmental health and climate (Cabernard et al., Reference Cabernard, Pfister, Oberschelp and Hellweg2022; Muncke et al., Reference Muncke, Andersson, Backhaus, Belcher, Boucher, Carney Almroth, Collins, Geueke, Groh, Heindel, von Hippel, Legler, Maffini, Martin, Peterson Myers, Nadal, Nerin, Soto, Trasande, Vandenberg, Wagner, Zimmermann, Thomas Zoeller and Scheringer2023; Trasande et al., Reference Trasande, Nelson, Al Shawabkeh, Barrett, Buckley, Dabelea, Dunlop, Herbstman, Meeker, Naidu, Newschaffer, Padula, Romano, Ruden, Sathyanarayana, Schantz, Starling, Hamra, Smith and Karr2024). The evidence base shows that due to the persistent and cumulative nature of plastic pollution (Geyer et al., Reference Geyer, Jambeck and Lavender-Law2017), plastic removal and recycling technologies cannot keep pace with the scale of the global plastic pollution crisis (e.g., Borrelle et al., Reference Borrelle, Ringma, Law, Monnahan, Lebreton, McGivern, Murphy, Jambeck, Leonard, Hilleary, Eriksen, Possingham, De Frond, Gerber, Polidoro, Tahir, Bernard, Mallos, Barnes and Rochman2020; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Shiran, Bailey, Cook, Stuchtey, Koskella, Velis, Godfrey, Boucher, Murphy, Thompson, Jankowska, Castillo, Pilditch, Dixon, Koerselman, Kosior, Favoino, Gutberlet, Baulch, Atreya, Fischer, He, Petit, Sumaila, Neil, Bernhofen, Lawrence and Palardy2020; OECD, 2022). Even if plastics production is reduced between the range of 1%–3% per year, global plastic pollution will continue its upward trend as cumulative production reaches at least 20,000 million metric tonnes of plastic by 2040 (Scientists’ Coalition, 2024a). In light of this, we call for an ambitious global reduction target for “virgin plastics” or primary plastic polymers (PPP), defined as “plastic materials made of synthetic and semi-synthetic polymers that are used for the first time to create plastic products in any form, including thermoplastic, thermoset, elastomer and composite resins made from bio-based and fossil-based feedstocks” (Scientists’ Coalition, 2024b).

The transition away from non-essential single-use plastics is fundamental for ending plastic pollution. The growing production and substantive subsidies to oil and gas extraction are keeping the price of PPP artificially low, with severe economic, societal and environmental repercussions (EEA, 2022). The global market has been flooded with cheap PPP, resulting in conditions where recycled plastics cannot compete with virgin plastics and are losing market shares despite global efforts to enhance plastics recycling. The low price of fossil plastic feedstock further favors the production and consumption of single-use (UNDP, n.d.) and short-lived plastics (OECD, 2022). This means that market incentives are weak for producing durable plastic products. Furthermore, because single-use and short-lived products typically have very low recycling potential, their risk of material loss from the supply chain and their likelihood of ending up as pollution in the environment is high. By implementing a legally binding global PPP reduction target, the material becomes more valuable as less is produced, which in turn can help overcome the growing negative economic, societal, environmental and human health impacts of non-essential plastics (McGlade et al., Reference McGlade, Samy Fahim, Green, Landrigan, Andrady, Costa, Geyer, Gomes, Shau Hwai, Jambeck, Li, Rochman, Ryan, Thiel, Thompson, Townsend, Turra and Maes2021). Additionally, we recommend plastics and their alternatives and substitutes be assessed against the “essential use concept” (Cousins et al., Reference Cousins, De Witt, Glüge, Goldenman, Herzke, Lohmann, Miller, Ng, Patton, Scheringer, Trier and Wang2021) as currently applied in the Montreal Protocol. The further up the supply chain the global responses are, the safer, more affordable and effective the implementation mechanisms will be (Simon et al., Reference Simon, Raubenheimer, Urho, Unger, Azoulay, Farrelly, Sousa, van Asselt, Carlini, Sekomo, Schulte, Busch, Wienrich and Weiand2021).

The high complexity and low transparency of the petrochemical industry coupled with the lack of willingness to disclose production data also presents a significant challenge to establishing effective global and national reduction targets. The development of robust essentiality, hazard-based safety, sustainability and transparency criteria will be crucial in guiding the development and implementation of effective PPP reduction targets.

Finally, we stress the need for mandatory, time-bound global and national PPP reduction targets. The evidence is clear: We must go upstream to the source of the global plastics crisis and turn off the plastic pollution tap by reducing PPP production.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2024.8.

Comments

No accompanying comment.