This abstract was awarded the student prize for best poster original communication.

Low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with reduced diet quality( Reference Freisling, Elmadfa and Gall 1 ), gestational weight gain (GWG) outside of Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines( 2 ) and poorer pregnancy outcomes( Reference Agyemang, Vrijkotte and Droomers 3 ). A paucity of data exists regarding the response of women of low SES to interventions in pregnancy. We aimed to determine if response to a low glycaemic index (GI) dietary intervention, measured by changes in diet and excess GWG, differed across women of high/low educational attainment and neighbourhood deprivation.

This was secondary data analysis of 754 women recruited to the ROLO study( Reference Walsh, McGowan and Mahony 4 ) (Randomised cOntrol trial of a LOw glycaemic index diet in pregnancy to prevent macrosomia) between 2007 and 2011. The intervention consisted of a 2-hour low GI education session with a dietitian. Change in GI and nutrient intakes were measured using 3-day food diaries pre- and post-intervention. Weight, height and BMI (kg/m2) were measured at the first antenatal visit. GWG was recorded throughout pregnancy. Excess GWG was categorised as per the 2009 IOM guidelines. Neighbourhood deprivation indices were assigned using an Irish census data index( Reference Haase and Pratschke 5 ), and categorised as advantaged or disadvantaged. Self-reported education was categorised as achieved or did not achieve 3rd level education.

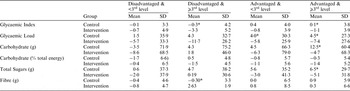

The mean changes in nutrient intakes from pre-intervention to post-intervention are shown in the table below. The intervention significantly reduced GI in both the “advantaged & ⩾3rd level” and “disadvantaged & ⩾3rd level” groups. The intervention did not significantly change any of the nutrient intakes from pre-intervention to post-intervention in the “disadvantaged and <3rd level” group.

The intervention significantly reduced excess GWG, compared to the control, only among those in the “disadvantaged and ⩾3rd level” (31·8 % vs. 69·7 %, respectively; P = 0·006) and “advantaged and ⩾3rd level” (34·5 % vs. 55·5 %, respectively; P = 0·001). There were no significant differences in excess GWG between the intervention and control in the “disadvantaged and <3rd level” and “advantaged and <3rd level”.

* Represents P value <0·05 on independent sample t test between intervention and control.

Pregnant women with 3rd level education, regardless of the neighbourhood in which they lived, were most receptive to a dietary intervention. The education session was not effective in reducing GI or excess GWG among less educated women. Tailored approaches are required to increase effectiveness of interventions among women of lower educational attainment.