- HPA

hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal

- 11β-HSD1

11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1

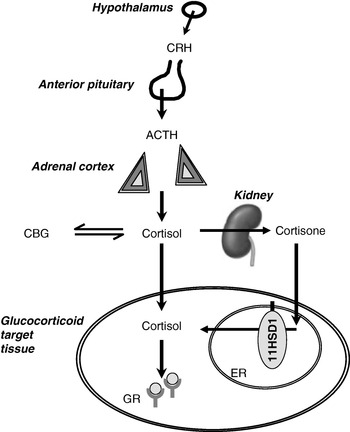

The intracellular enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1) catalyses the interconversion of the active 11-hydroxy glucocorticoid cortisol with its inactive 11-keto metabolite cortisone. 11β-HSD1 is predominantly a reductase in most circumstances, regenerating cortisol from cortisone and thereby increasing intracellular cortisol concentrations. Since 11β-HSD1 is co-localised with glucocorticoid receptors in many cells, including in adipose tissue and liver, it is ideally positioned to amplify local glucocorticoid action (Fig. 1). It follows that chronically increasing 11β-HSD1 activity might increase glucocorticoid receptor activation and thereby promote obesity and its associated metabolic complications, while decreasing 11β-HSD1 may be a strategy to reduce glucocorticoid action selectively in some tissues and thereby reverse the metabolic complications of obesity. In support of this hypothesis transgenic mice over-expressing 11β-HSD1 in adipose tissue develop obesity with all the features of the metabolic syndrome (Masuzaki et al. Reference Masuzaki, Paterson, Shinyama, Morton, Mullins, Seckl and Flier2001, Reference Masuzaki, Yamamoto, Kenyon, Elmquist, Morton and Paterson2003), while 11β-HSD1-knock-out mice are protected from obesity and its metabolic complications (Kotelevtsev et al. Reference Kotelevtsev, Holmes, Burchell, Houston, Scholl, Jamieson, Best, Brown, Edwards, Seckl and Mullins1997; Morton et al. Reference Morton, Holmes, Fievet, Staels, Tailleux, Mullins and Seckl2001, Reference Morton, Paterson, Masuzaki, Holmes, Staels, Fievet, Walker, Flier, Mullins and Seckl2004a). Against this background there has been intense interest in developing inhibitors of 11β-HSD1 to reduce glucocorticoid action selectively within metabolically-active tissues such as adipose and liver, without blocking essential actions of glucocorticoids during stress. Indeed, to date approximately eighteen pharmaceutical companies and other organisations have filed patents for 11β-HSD1 inhibitors.

Fig. 1. Interactions between the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (11HSD) in the control of glucocorticoid receptor activation. CRH, corticotrophin-releasing hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotrophin; CBG, corticosteroid-binding globulin; 11HSD1, 11HSD type 1; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GR, glucocorticoid receptor. In the kidney cortisol is converted to cortisone by 11HSD type 2.

The influence of 11β-HSD1 in mice and its potential as a therapeutic target in human subjects has been extensively reviewed elsewhere (Seckl & Walker, Reference Seckl and Walker2001, Reference Seckl and Walker2004; Seckl et al. Reference Seckl, Morton, Chapman and Walker2004; Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Walker, Bujalska, Draper, Lavery, Cooper, Hewison and Stewart2004b). The present article will focus on what is known of the physiological role of glucocorticoids in the regulation of fuel partitioning in liver and adipose tissue, how this process is modulated by 11β-HSD1, and how it may be perturbed in obesity. It draws, wherever possible, on results of experiments in human subjects.

Glucocorticoids and control of energy partitioning

Responses to starvation and stress

Many investigators have remarked that the evolution of the control of energy balance has been driven by intermittent but prolonged periods of starvation and malnutrition, rather than by relatively short periods of ample nutrition such as most individuals enjoy today. Just one of the pathways that respond to undernutrition is the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, controlling the secretion of cortisol from the adrenal cortex (Fig. 1). On starvation, cortisol levels rise (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Faber, Andrew, Gibney, Elia, Lobley, Stubbs and Walker2004). A similar rise in cortisol is induced by physical stressors, including trauma and sepsis. In addition, cortisol exhibits marked diurnal variation and levels are highest on waking. There are also small rises in cortisol secretion after each meal (Rosmond et al. Reference Rosmond, Dallman and Bjorntorp1998). The mechanisms of activation of the HPA axis in starvation are poorly understood; by analogy with the role of cytokines in mediating the cortisol response to sepsis and trauma, changes in adipokines may be important. For example, leptin has been shown to inhibit the HPA axis (Heiman et al. Reference Heiman, Ahima, Craft, Schoner, Stephens and Flier1997; Nowak et al. Reference Nowak, Pierzchala-Koziec, Tortorella, Nussdorfer and Malendowicz2002), so that a fall in leptin during starvation may be key to HPA axis activation (Ahima et al. Reference Ahima, Prabakaran, Mantzoros, Qu, Lowell, Maratos-Flier and Flier1996).

Following a rise in cortisol secretion into plasma, responses mediated via glucocorticoid receptors are relatively slow because they involve diffusion onto cytoplasmic receptors, translocation of these activated receptors to the nucleus, followed by alterations in gene transcription and translation. Responses to increases in cortisol may also be buffered through binding to corticosteroid-binding globulin within the intravascular compartment, although this binding is usually saturated in the upper physiological range of cortisol concentrations so that the response to increasing cortisol secretion is non-linear (Bamberger et al. Reference Bamberger, Schulte and Chrousos1996).

It is estimated that glucocorticoid receptors can interact as transcription factors with as many as 30% of genes, so it is not surprising that glucocorticoids induce a wide range of responses. An important effect on bioenergetics is to increase the turnover between free and stored energy substrates (for review, see Andrews & Walker, Reference Andrews and Walker1999). Thus, glucocorticoids increase cycling between glucose-6-phosphate and glycogen and between NEFA and TAG. The balance between free and stored substrates is determined by other signals, notably insulin, with the increased turnover resulting in an amplified response. Glucocorticoids also induce protein catabolism and gluconeogenesis, while decreasing liver mitochondrial β-oxidation (Morton et al. Reference Morton, Holmes, Fievet, Staels, Tailleux, Mullins and Seckl2001), thus encouraging hepatic release of fatty acids and glucose as energy for peripheral tissues. In addition, glucocorticoids alter signalling of other hormones that regulate energy balance, including catecholamines and insulin. Within the pancreas, glucocorticoids inhibit insulin secretion (Delaunay et al. Reference Delaunay, Khan, Cintra, Davani, Ling, Andersson, Ostenson, Gustafsson, Efendic and Okret1997). In the brain they stimulate food intake, particularly of fat (Castonguay, Reference Castonguay1991) and sugar (Epel et al. Reference Epel, Lapidus, McEwen and Brownell2001). All these acute effects increase the capacity for generation of energy to support skeletal muscle metabolism over a few hours or days and thus enhance the ability to ‘fight or flight’.

In addition to their effects on energy metabolism, glucocorticoids orchestrate many other aspects of the stress response that optimise survival following trauma or infection (Sapolsky et al. Reference Sapolsky, Romero and Munck2000). They induce euphoria, prevent sleep, suppress hippocampal memory retention, potentiate vasoconstrictor responses, enhance renal Na retention, suppress reproductive function and promote resolution of inflammatory responses by the innate immune system. They promote differentiation of immune and related cells, including pre-adipocytes.

Chronic glucocorticoid excess

Although helpful in adapting to short-term stress, excessive glucocorticoid action in the long term becomes maladaptive, particularly if this excessive action occurs in the absence of starvation. This situation is exemplified in Cushing's syndrome, in which elevated circulating levels of glucocorticoids, as a result of either iatrogenic anti-inflammatory treatment or pathological secretion of cortisol from the adrenal cortex, result in weight gain, myopathy, hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, mood disturbance, infertility and many other features (Newell-Price et al. Reference Newell-Price, Bertagna, Grossman and Nieman2006).

Given that glucocorticoids promote the delivery of fuel to skeletal muscle, the increase in TAG stores in adipose tissue in Cushing's syndrome appears paradoxical. This paradox probably reflects the combination of elevated glucocorticoid action with elevated insulin levels in individuals who are able to eat unrestricted energy and are not consuming fuel by exercising heavily (Dallman et al. Reference Dallman, la Fleur, Pecoraro, Gomez, Houshyar and Akana2004). In these circumstances fatty acid esterification predominates over lipolysis and, combined with stimulation of pre-adipocyte differentiation, results in expansion of adipose tissue size.

Cushing's syndrome is characterised by central (visceral) obesity, with relative sparing of subcutaneous adipose tissue. This outcome probably reflects higher expression of glucocorticoid receptors in visceral adipose tissue (Bronnegard et al. Reference Bronnegard, Arner and Hellstrom1990).

Responses to overnutrition and obesity

The parallels between the clinical features of Cushing's syndrome and the features of the metabolic syndrome (visceral obesity, hyperglycaemia, hypertension) led to the hypothesis that obesity is associated with glucocorticoid excess (Bjorntorp, Reference Bjorntorp1991). In several monogenic rodent models obesity is accompanied by elevated circulating glucocorticoid levels, and the obesity is prevented by adrenalectomy. Hyperactivity of the HPA axis was thought to reflect chronic stress. However, although there is some evidence for greater stress responsiveness of the HPA axis in obesity (Rosmond et al. Reference Rosmond, Dallman and Bjorntorp1998; Epel et al. Reference Epel, McEwen, Seeman, Matthews, Castellazzo, Brownell, Bell and Ickovics2000), stress does not appear to explain HPA axis activation in metabolic syndrome (Brunner et al. Reference Brunner, Hemingway, Walker, Page, Clarke and Juneja2002). Most importantly, in human obesity it appears that cortisol secretion (Marin et al. Reference Marin, Darin, Amemiya, Andersson, Jern and Bjorntorp1992; Pasquali et al. Reference Pasquali, Cantobelli, Casimirri, Capelli, Bortoluzzi, Flamia, Labate and Barabara1993) is increased to match elevated metabolic clearance (Strain et al. Reference Strain, Zumoff, Kream, Strain, Levin and Fukushima1982; Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Phillips and Walker1998; Lottenberg et al. Reference Lottenberg, Giannella-Neto, Derendorf, Rocha, Bosco, Carvalho, Moretti, Lerario and Wajchenberg1998), and does not result in increased plasma cortisol concentrations. Indeed, plasma cortisol concentrations are generally lower amongst obese subjects (Ljung et al. Reference Ljung, Andersson, Bengtsson, Bjorntorp and Marin1996; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Soderberg, Lindahl and Olsson2000; Reynolds et al. Reference Reynolds, Syddall, Walker, Wood and Phillips2003), i.e. inverse to the effects on the HPA axis seen during starvation (see earlier; p. 2).

Glucocorticoid deficiency or blockade

Unfortunately, glucocorticoid deficiency (associated with Addison's disease or adrenocorticotrophin deficiency) does not lend itself to detailed investigation, since it is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate corticosteroid-replacement therapy. However, the clinical features are broadly the opposite of those in Cushing's syndrome, and include weight loss and hypoglycaemia.

The effects of the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist RU38486 (mifepristone) are broadly as predicted by the effects of glucocorticoids described earlier. Thus, RU38486 reduces blood glucose and ameliorates insulin resistance in ob/ob mice (Gettys et al. Reference Gettys, Watson, Taylor and Collins1997), streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice (Bitar, Reference Bitar2001) and high-fat-fed rats (Kusunoki et al. Reference Kusunoki, Cooney, Hara and Storlien1995), although it is less effective in Zucker obese rats (Havel et al. Reference Havel, Busch, Curry, Johnson, Dallman and Stern1996). In healthy human subjects, however, acute dosing with RU38486, although lowering serum TAG (Ottosson et al. Reference Ottosson, Marin, Karason, Elander and Bjorntorp1995) and basal hepatic glucose output (Garrel et al. Reference Garrel, Moussali, De Oliveira, Lesiege and Lariviere1995), has been reported to raise postprandial glucose and insulin concentrations without affecting energy balance (Jobin et al. Reference Jobin, de Jonge and Garrel1996). Furthermore, in obese patients RU38486 does not reverse hyperinsulinaemia or alter appetite (Kramlik et al. Reference Kramlik, Altemus and Castonguay1993). These paradoxical results may be explained because RU38486 blocks glucocorticoid receptors involved in negative feedback control and this action produces compensatory activation of the HPA axis. Moreover, RU38486 is also a progesterone receptor antagonist, and this action may influence energy homeostasis (Picard et al. Reference Picard, Wanatabe, Schoonjans, Lydon, O'Malley and Auwerx2002).

To avoid systemic effects RU38486 has been targetted to the liver by conjugation to a bile acid. This strategy has shown that liver glucocorticoid receptor blockade is sufficient to improve hepatic glucose output and blood glucose concentrations in Zucker obese rats (Jacobson et al. Reference Jacobson, von Geldern, Ohman, Osterland, Wang and Zinker2005), a conclusion that is supported by experiments in which glucocorticoid receptor translation has been prevented by transgenesis (Opherk et al. Reference Opherk, Tronche, Kellendonk, Kohlmuller, Schulze, Schmid and Schutz2004) or by using in vivo anti-sense RNA constructs (Watts et al. Reference Watts, Manchem, Leedom, Rivard, McKay and Bao2005). Non-steroidal glucocorticoid receptor modulators that are apparently liver-specific have also been described, with promising effects in animal models of diabetes mellitus (Link et al. Reference Link, Sorensen, Patel, Grynfarb, Goos-Nilsson and Wang2005). Unfortunately, none of these compounds has yet been evaluated in human subjects.

In summary, chronic glucocorticoid excess induces obesity and associated metabolic syndrome. Although glucocorticoid deficiency has not been studied as extensively as glucocorticoid excess, there are sufficient data to suggest that reducing glucocorticoid action may be a valuable strategy to lower blood glucose and fatty acid levels and enhance insulin sensitivity. Effects on long-term control of body weight have, however, been inadequately tested.

11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in the control of energy partitioning

The evidence that metabolism of glucocorticoids within target tissues can influence access of ligands to receptors over and above the control exerted by the HPA axis is remarkably strong in mice. The data suggest that adipose tissue, as much as liver, is the key target tissue in which glucocorticoid action influences susceptibility to obesity and associated metabolic complications. Interestingly, 11β-HSD1 activity in skeletal muscle is relatively trivial and has not been shown to be important. Transgenic over-expression of 11β-HSD1 within adipose tissue results in elevated intra-adipose glucocorticoid levels, with associated obesity, hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia and hypertension (Masuzaki et al. Reference Masuzaki, Paterson, Shinyama, Morton, Mullins, Seckl and Flier2001, Reference Masuzaki, Yamamoto, Kenyon, Elmquist, Morton and Paterson2003). However, a similar level of over-expression in liver does not induce obesity or hyperglycaemia, although there are changes in lipidaemia, insulin sensitivity and blood pressure (Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Morton, Fievet, Kenyon, Holmes, Staels, Seckl and Mullins2004). 11β-HSD1-knock-out mice on a high-fat diet are protected from obesity and metabolic complications (Kotelevtsev et al. Reference Kotelevtsev, Holmes, Burchell, Houston, Scholl, Jamieson, Best, Brown, Edwards, Seckl and Mullins1997; Morton et al. Reference Morton, Holmes, Fievet, Staels, Tailleux, Mullins and Seckl2001, Reference Morton, Paterson, Masuzaki, Holmes, Staels, Fievet, Walker, Flier, Mullins and Seckl2004a). Pharmacological inhibition of 11β-HSD1 has also been achieved in mice. These inhibitors are effective in enhancing hepatic insulin sensitivity and lowering blood glucose in diabetic mice and induce weight loss in obese mice, at least in the short term (Alberts et al. Reference Alberts, Engblom, Edling, Forsgren, Klingstrom, Larsson, Ronquist-Nii, Ohman and Abrahmsen2002, Reference Alberts, Nilsson, Selen, Engblom, Norlin and Klingstrom2003; Hermanowski-Vosatka et al. Reference Hermanowski-Vosatka, Balkovec, Cheng, Chen, Hernandez and Koo2005).

Although not the focus of the present review, it is worth noting that some of the actions of 11β-HSD1 inhibitors in mice may operate in tissues other than liver and adipose. For example, 11β-HSD1 inhibition reduces the progression of atheroma in apoE-knock-out mice (Hermanowski-Vosatka et al. Reference Hermanowski-Vosatka, Balkovec, Cheng, Chen, Hernandez and Koo2005), perhaps reflecting actions on the enzyme within the vessel wall (Hadoke et al. Reference Hadoke, Macdonald, Logie, Small, Dover and Walker2006) or within immune cells (Gilmour et al. Reference Gilmour, Coutinho, Cailhier, Man, Clay, Thomas, Harris, Mullins, Seckl, Savill and Chapman2006). Furthermore, there may be effects of 11β-HSD1 on central control of appetite (Densmore et al. Reference Densmore, Morton, Mullins and Seckl2006) and on insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells (Davani et al. Reference Davani, Khan, Hult, Martensson, Okret, Efendic, Jornvall and Oppermann2000). These actions remain largely unexplored in human subjects.

The ability of the human liver to convert pharmacological doses of cortisone into cortisol has been recognised since the earliest days of anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid therapy. What is the evidence that 11β-HSD1 plays the same key role in determining glucocorticoid action in liver and/or adipose tissue in human subjects as it does in mice?

Contribution of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 to the glucocorticoid pool

The proportion of the plasma cortisol pool derived from regeneration of cortisol by 11β-HSD1 has recently been quantified and found to be substantial. These measurements were achieved in human subjects (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Smith, Jones and Walker2002) using a novel stable-isotope tracer, in which metabolism of [9,11,12,12-2H4]cortisol is compared with metabolism of [9,12,12-2H3]cortisol; 11β-reductase activity generates [2H3]cortisol but not [2H4]cortisol, so that the ratio between the two can be used to calculate cortisol regeneration rates. Basu et al. (Reference Basu, Singh, Basu, Chittilapilly, Johnson, Toffolo, Cobelli and Rizza2004) have estimated that peripheral regeneration of cortisol in healthy men is approximately 11 nmol/min at a time when adrenal cortisol secretion is approximately 38 nmol/min. All this peripheral regeneration of cortisol could be accounted for by its appearance in the hepatic vein, suggesting that it occurs almost entirely in the splanchnic circulation.

It remains uncertain how much of this splanchnic regeneration of cortisol occurs outside of the liver. Andrew et al. (Reference Andrew, Westerbacka, Wahren, Yki-Jarvinen and Walker2005) have measured the regeneration of cortisol in the liver following oral cortisone administration and have deduced that approximately one-third of splanchnic 11β-HSD1 activity is hepatic while two-thirds may be accounted for by visceral components, probably visceral adipose tissue. Importantly, these conclusions have yet to be validated by direct measurements either in the portal vein or in venous drainage across other potential major sites of 11β-HSD1 activity such as subcutaneous adipose tissue. Indeed, cortisol concentrations in the portal vein (Aldhahi et al. Reference Aldhahi, Mun and Goldfine2004) or superficial epigastric veins (Katz et al. Reference Katz, Mohamed-Ali, Wood, Yudkin and Coppack1999) have not been shown to be greater than those in the arterial circulation, although cortisone levels in veins draining adipose tissue are lower. It is known, however, that infusion of cortisone directly into subcutaneous adipose tissue results in local production of cortisol (Sandeep et al. Reference Sandeep, Andrew, Homer, Andrews, Smith and Walker2005).

Regulation of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1

A wide variety of factors are known to regulate 11β-HSD1 mRNA levels and activity in rodents and in isolated cells in culture (for review, see Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Walker, Bujalska, Draper, Lavery, Cooper, Hewison and Stewart2004b). A number of these factors are important modulators of energy balance, including insulin, liver X receptor agonists, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor 1, cytokines and PPAR agonists. Intriguingly, high-fat feeding of mice (Morton et al. Reference Morton, Ramage and Seckl2004b) or rats (Drake et al. Reference Drake, Livingstone, Andrew, Seckl, Morton and Walker2005) results in down-regulation of 11β-HSD1 selectively within the adipose tissue. Although a tissue-specific promoter for 11β-HSD1 has been identified in lung and placenta (Bruley et al. Reference Bruley, Lyons, Worsley, Wilde, Darlington, Morton, Seckl and Chapman2006), the basis for tissue-specific regulation in liver and adipose tissue is not known.

Recent research has begun to address the regulation of 11β-HSD1 in healthy human subjects, and suggests that the enzyme is influenced by nutritional status. Thus, a single mixed meal induces a rise in whole-body rates of regeneration of cortisol by 11β-HSD1, although the organ responsible for this process is not clear (Basu et al. Reference Basu, Singh, Basu, Johnson and Rizza2006). Recent data (Wake et al. Reference Wake, Homer, Andrew and Walker2006) suggest that it is mediated by hyperinsulinaemia. In the longer term, energy restriction in obese subjects has been associated with an increase in 11β-HSD1 in subcutaneous adipose tissue (Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Moore, Clark, Holder, Shakespeare and Stewart2004a), although this finding is not universal (Engeli et al. Reference Engeli, Bohnke, Feldpausch, Gorzelniak, Heintze, Janke, Luft and Sharma2004), perhaps because of differences in the diet being followed at the time biopsies were obtained. More investigation is required, but it appears that 11β-HSD1 may respond to signals of energy balance in an analogous way to the HPA axis, and modulate tissue levels of cortisol over and above changes in plasma cortisol concentrations.

Consequences of loss of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in human subjects

Results from clinical trials with novel selective 11β-HSD1 inhibitors are eagerly awaited. In the meantime, pharmacological inhibition of 11β-HSD1 with the anti-ulcer drug carbenoxolone has provided evidence that cortisol regeneration influences insulin sensitivity, particularly glycogen turnover, in healthy human subjects and in patients with type 2 diabetes (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Connacher, Lindsay, Webb and Edwards1995; Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Rooyackers and Walker2003). However, carbenoxolone is neither selective nor very potent and does not appear to inhibit 11β-HSD1 in adipose tissue, perhaps explaining its lack of efficacy in obesity (Sandeep et al. Reference Sandeep, Andrew, Homer, Andrews, Smith and Walker2005).

Congenital deficiency of 11β-HSD1 (‘apparent cortisone reductase deficiency’) has been described (Phillipou et al. Reference Phillipou, Palermo and Shackleton1996), but the phenotype is dominated by the consequences of enhanced metabolic clearance rate of cortisol (a result of the lack of regeneration in peripheral tissues), with compensatory activation of the HPA axis resulting in adrenal androgen excess, hirsutism and oligomenorrhoea in women. These women do not appear to be protected from obesity and any influence on susceptibility to metabolic complications is questionable. The molecular basis for the disorder is also complex. It appears most likely that inactivating mutations in hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Draper et al. Reference Draper, Walker, Bujalska, Tomlinson, Chalder and Arlt2003), an enzyme closely associated with 11β-HSD1 in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, result in an inadequate supply of NADPH cofactor for 11β-HSD1 reductase activity. In hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient mice this situation results in a ‘switch’ of 11β-HSD1 to the dehydrogenase direction (Lavery et al. Reference Lavery, Walker, Draper, Jeyasuria, Marcos, Shackleton, Parker, White and Stewart2006). As yet, it is unclear whether variations in hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity provide a means for post-transcriptional physiological regulation of 11β-HSD1 activity (Hewitt et al. Reference Hewitt, Walker and Stewart2005).

Elevated 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in obesity

Given the similarities between Cushing's syndrome and idiopathic obesity, coupled with the lack of elevation of plasma cortisol levels in the latter, it was hypothesised that increases in 11β-HSD1 within adipose tissue may be a causative factor in obesity (Bujalska et al. Reference Bujalska, Kumar and Stewart1997). Initial studies relied on measurements of cortisol:cortisone metabolites in urine (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Phillips and Walker1998; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Ingram, Anderson, Morrison, Davies and Connell1999), an assay that is probably unreliable in obesity, when several cortisol and cortisone-metabolising enzymes are dysregulated (Andrew et al. Reference Andrew, Phillips and Walker1998). Of greater importance, the conversion of an oral dose of cortisone into cortisol on first-pass metabolism in the liver was found to be lower, not higher, in obesity (Stewart et al. Reference Stewart, Boulton, Kumar, Clark and Shackleton1999). However, parallel studies in obese rodents revealed tissue-specific dysregulation of 11β-HSD1, with a reduction in enzyme activity and mRNA levels in liver accompanied by an increase in the enzyme in adipose tissue (Livingstone et al. Reference Livingstone, Jones, Smith, Andrew, Kenyon and Walker2000). A number of groups (Rask et al. Reference Rask, Olsson, Soderberg, Andrew, Livingstone, Johnson and Walker2001, Reference Rask, Walker, Soderberg, Livingstone, Eliasson, Johnson, Andrew and Olsson2002; Paulmyer-Lacroix et al. Reference Paulmyer-Lacroix, Boullu, Oliver, Alessi and Grino2002; Lindsay et al. Reference Lindsay, Tataranni, Permana, Livingstone, Wake and Walker2003; Wake et al. Reference Wake, Rask, Livingstone, Soderberg, Olsson and Walker2003; Engeli et al. Reference Engeli, Bohnke, Feldpausch, Gorzelniak, Heintze, Janke, Luft and Sharma2004; Kannisto et al. Reference Kannisto, Pietilainen, Ehrenborg, Rissanen, Kaprio, Hamsten and Yki-Jarvinen2004) have now confirmed this observation in biopsies of subcutaneous adipose tissue from obese people. Nonetheless, there may not be a relationship between 11β-HSD1 in visceral adipose tissue and body composition (Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Sinha, Bujalska, Hewison and Stewart2002; Goedecke et al. Reference Goedecke, Wake, Levitt, Lambert, Collins, Morton, Seckl and Walker2006). Importantly, in both the whole body (Sandeep et al. Reference Sandeep, Andrew, Homer, Andrews, Smith and Walker2005) and the splanchnic circulation (Basu et al. Reference Basu, Singh, Basu, Chittilapilly, Johnson, Toffolo, Cobelli and Rizza2005) there is no difference in cortisol regeneration rates measured with a [2H4]-cortisol tracer between obese and lean subjects, presumably because an up-regulation in adipose tissue is balanced by a down-regulation in liver. However, direct in vivo measurements using microdialysis in subcutaneous adipose tissue suggest a substantial increase in the rate of conversion of cortisone to cortisol (Sandeep et al. Reference Sandeep, Andrew, Homer, Andrews, Smith and Walker2005). The subtle counter-regulatory mechanisms that operate between different tissues, and different sites of adipose tissue, may be key to how glucocorticoids modulate predisposition to obesity and associated morbidities.

To understand the basis for the increase in adipose 11β-HSD1 in obesity, several non-coding polymorphisms in the HSD11B1 gene encoding the enzyme have been identified (Draper et al. Reference Draper, Echwald, Lavery, Walker, Fraser and Davies2002; Nair et al. Reference Nair, Lee, Lindsay, Walker, Tataranni, Bogardus, Baier and Permana2004). None of these polymorphisms is associated with obesity, but they have been linked to the increased risk of diabetes and hypertension in two populations (Franks et al. Reference Franks, Knowler, Nair, Koska, Lee, Lindsay, Walker, Looker, Permana, Tataranni and Hanson2004; Nair et al. Reference Nair, Lee, Lindsay, Walker, Tataranni, Bogardus, Baier and Permana2004). Moreover, a polymorphism that predicts lower 11β-HSD1 expression (Draper et al. Reference Draper, Walker, Bujalska, Tomlinson, Chalder and Arlt2003) and is protective against diabetes is also under-represented in patients who are both obese and have polycystic ovary syndrome (Gambineri et al. Reference Gambineri, Vicennati, Tomassoni, Pagotto, Pasquali and Walker2006), in which lower 11β-HSD1 may enhance cortisol clearance and increase adrenal androgen production. This finding suggests that 11β-HSD1 may not underpin the accumulation of TAG in adipose tissue, but rather may determine the severity of the metabolic consequences when obesity occurs.

Conclusions

The identification of 11β-HSD1 as a local amplifier of glucocorticoid receptor activation has provided novel insights into many facets of the stress response. This new paradigm allows that responses can be regulated not only by the HPA axis but also by the sensitivity of each cell and tissue to a given level of cortisol in the circulation. Thus far, investigations in human subjects have only scratched at the surface in understanding the influence of 11β-HSD1 in many different components of the stress response, and have focused on its role in energy partitioning and in obesity. Here, increased regeneration of cortisol within adipose tissue has caught the imagination of many investigators, and the potential for enzyme inhibition in the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes is an exciting, but as yet unproven, strategy. Arguably, the more important observations are the initial suggestions that 11β-HSD1 is exquisitely regulated, including by feeding, so that the enzyme may be a key component in the homeostatic adaptation to variations in macronutrient intake.

Acknowledgements

Our research is supported in large part by the British Heart Foundation and Wellcome Trust.